Published online Feb 15, 2026. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v17.i2.113992

Revised: October 19, 2025

Accepted: December 26, 2025

Published online: February 15, 2026

Processing time: 149 Days and 14 Hours

Diabetic neuropathy is a neurodegenerative complication of diabetes mellitus that occurs due to various factors, with oxidative stress, neuroinflammation and neurotrophic signalling impairment being the major causes.

To evaluate the neuroprotective effects of a polyherbal extract (PHE) prepared from Citrullus colocynthis, Curcuma longa, and Myristica fragrans in diabetic rats.

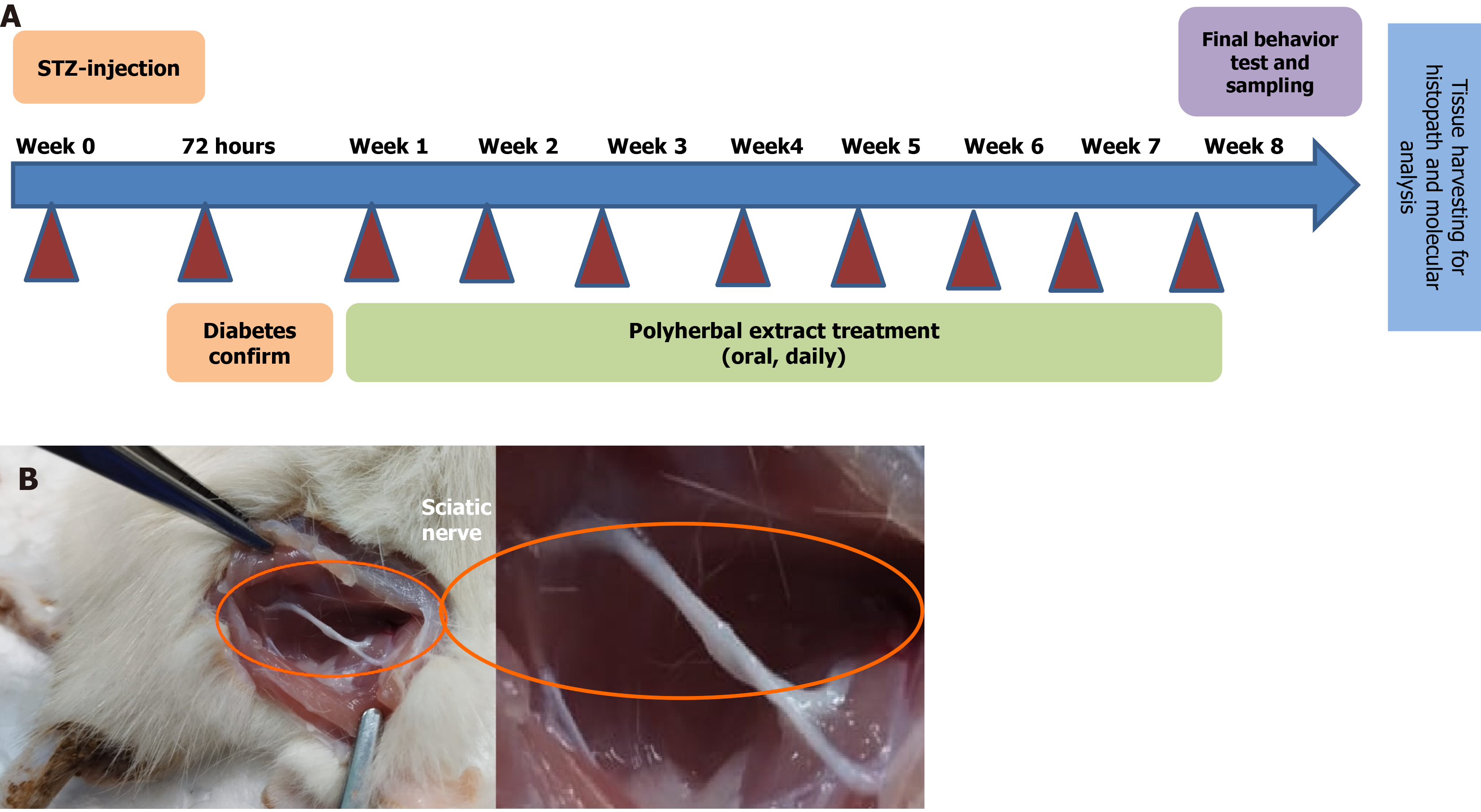

Type 2 diabetes was induced in rats with a single intraperitoneal injection of streptozotocin, and those with fasting blood glucose levels of > 250 mg/dL were included for further studies. The animals were categorised into five groups: Control, diabetic, diabetic + PHE, control + PHE and diabetic + metformin. These treatments were administered orally for 8 weeks. Behavioral tests comprised the hot plate, tail-flick, acetone drop and rotarod tests. Serum glucose, insulin, glycosylated haemoglobin and lipid profile analyses were performed, along with oxidative stress (malondialdehyde, reduced glutathione, superoxide dismutase, catalase and glutathione-S-transferase) and pro-inflammatory (tumour necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6) markers. Neurotrophic factors were measured, and the pancreas, liver and sciatic nerve were histologically examined.

This study demonstrated that PHE exerts a significant metabolic regulatory effect in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat models. PHE treatment led to a marked reduction of 30.17% in fasting blood glucose levels, indicating potent antihyperglycemic activity, and also restored the lipid profile, enhanced antioxidant defenses, and reduced neuroinflammation. Serum insulin levels were significantly increased in diabetic rats receiving PHE, suggesting potential stimulation or preservation of pancreatic β-cells. Furthermore, behavioral impairments and histological damage were notably reversed following PHE administration.

The PHE derived from Curcuma longa, Myristica fragrans, and Citrullus colocynthis mitigates diabetic neuropathy through synergistic chemical-biological interactions targeting key mediators of oxidative stress and inflammation. These findings support the need for comprehensive evaluation of this formulation as a potential therapeutic candidate. This study enhances the current understanding of integrative approaches for managing chronic diabetic complications and provides further evidence supporting the therapeutic potential of plant-based compounds.

Core Tip: Diabetic neuropathy represents the primary complication of diabetes, characterized by oxidative stress, inflammation, and impaired neurotrophic signaling. In streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats, a polyherbal extract derived from Curcuma longa, Myristica fragrans, and Citrullus colocynthis significantly enhanced metabolic parameters, improved lipid profile and promoted antioxidant defense, and neurobehavioral outcomes. It reversed behavioral impairments and histological damage by lowering hyperglycemia, raising insulin levels, and reducing neuroinflammation and oxidative stress. These findings demonstrate the neuroprotective qualities of polyherbal extract and encourage more research into plant-based remedies for diabetic neuropathy.

- Citation: Kausar MA, Parveen K, Anwar S, Khan YS, Saleh AA, Ahmed MAA, Siddiqui WA, Parvez S. Neuroprotective potential of a plant-based intervention in diabetic neuropathy: Biochemical and behavioral insights from a streptozotocin-induced rat model. World J Diabetes 2026; 17(2): 113992

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v17/i2/113992.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v17.i2.113992

Diabetic neuropathy (DN) is a prevalent and painful complication of diabetes mellitus (DM) that affects approximately 50% of individuals with diabetes globally[1]. With progressive neuronal damage, signals are sent to nerve tissues in the pain sub-syndrome of neural disorders, resulting in numbness and impaired motor functions, thereby drastically affecting the quality of life. The pathogenesis of DN is multifaceted and involves oxidative stress, inflammation and dyslipoproteinaemia, all of which aggravate neuronal injury and dysfunction[2-4].

One of the most significant mechanisms in DN is oxidative stress, which is caused by the excessive generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) under hyperglycaemic conditions[5]. The generation of ROS, along with reactive nitrogen species, overwhelms all endogenous antioxidant systems, including glutathione-S-transferase (GST), reduced glutathione (GSH), catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD), leading to lipid peroxidation (LPO) and consequently cellular damage, evidenced by an increase in malondialdehyde (MDA) levels. These parameters can be improved by enhancing antioxidant defences, thus ameliorating oxidative damage and normalising neuronal function in diabetic models[6]. Furthermore, interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) are pro-inflammatory mediators associated with the chronic inflammatory process, aggravating neuronal degeneration via apoptosis and demyelination[1,7,8].

Dyslipidaemia, which usually co-exists with type 2 diabetes, is often ignored in DN. Lipid profile alterations, marked by increased triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels and decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels, result in peripheral nerve and endothelial dysfunction, fatty infiltration into Schwann cells and an augmented oxidative burden. These lipid disturbances compromise the vascular supply to nerves, contributing to the onset and severity of DN[9].

Moreover, alterations in lipid profile interfere with the expression and action of neurotrophic factors in patients with diabetes, specifically brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and nerve growth factor (NGF), which are essential for neuronal survival, axonal growth and synaptic plasticity. NGF and BDNF may halt nerve damage and trigger functional recovery; thus, their deficiency in patients with diabetes appears to be correlated with sensory loss and impairment of nerve regeneration[10,11]. Recently, meta-analyses demonstrated that serum BDNF is considerably diminished in patients with type 2 diabetes having complications such as retinopathy and cognitive impairments[12,13]. Decreased NGF levels have also been linked to advancing DN[14].

Considering the multifaceted nature of DN, therapeutic agents that can target several pathological pathways simultaneously have attracted immense research attention. Polyherbal formulations containing various medicinal plants with complementary pharmacological properties are promising candidates for therapeutic applications. Such formulations can potentially act synergistically and enhance the therapeutic effects while minimising the side effects. This approach is important because current pharmacotherapies have limitations, providing only symptomatic relief and failing to address the underlying disease. Therefore, the search for herbal medications continues to attract immense attention. Phytochemicals endowed with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, lipid-modulating and neuroprotective activities are currently being investigated as multi-targeted agents for tackling DN[5,15]. In this study, a polyherbal extract (PHE) composed of three medicinally important plants, Citrullus colocynthis (C. colocynthis, bitter apple), Curcuma longa (C. longa, Turmeric) and, both the aril and nut of Myristica fragrans (M. fragrans, nutmeg and mace), was evaluated to explore the combined effects of its bioactive constituents and therapeutic properties. These plants have traditionally been used in Ayurvedic medicine owing to their anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and anti-diabetic properties.

C. colocynthis (bitter apple) has been shown to exhibit hypoglycaemic and neuroprotective properties in diabetic models, and its phenolic and flavonoid constituents act as antioxidants and anti-inflammatory agents, ameliorating the metabolic and neural complications of DM[16]. C. longa (turmeric), a well-known source of curcumin, displays robust anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity via the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway and the enhancement of the natural antioxidant system and neurotrophic factors such as BDNF[17-19]. M. fragrans (nutmeg) has been used traditionally owing to its neurotonic and anxiolytic effects[20]. Recent studies have shown that bioactive compounds can improve antioxidant defences and modulate neurotransmission, which are useful for nerve repair and regeneration[21-23].

To determine the effect of PHE on DN, a streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rat model was used. This study evaluated the manifestations of DN via behavioral tests; serum biochemical analyses; determination of oxidative stress markers, pro-inflammatory cytokines and neurotrophic factors; and histopathological examination of the liver, pancreas and sciatic nerve. Thus, this study aimed to elucidate the multifaceted effects of PHE and provide insights into the complex mechanisms by which it exerts its neuroprotective effects.

STZ (Cat# S0130), metformin (Met, PHR1084-dia500MG), β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide 2’-phosphate reduced (Cat# N7505), thiobarbituric acid (Cat#T5500) and 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (Cat#237329) were procured from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States. Other chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade.

A fresh sample of C. colocynthis fruit, C. longa rhizome and M. fragrans (aril and nut) were procured from Herbal Garden, Jamia Hamdard. Botanical identification of each sample was done by the Taxonomist in Department of Botany, Jamia Hamdard, New Delhi, and voucher specimens were submitted for future reference. After being cleaned, the plant materials were dried and ground into a powder form with an electric grinder. Based on the results of the anti-diabetic pilot study performed in our laboratory, equal weights of each powdered plant part (1:1:1:1, w/w) were mixed. The coarse powder was then extracted for 3 days using Soxhlet equipment with ethanol. The extract was cooled and filtered to remove the leftover portions. Subsequently, concentrated extracts were dried using a low-pressure evaporator. The extracts were stored in an airtight bottle. PHE was dissolved using proper proportions in normal saline for the study.

The PHE, employed throughout the study, was previously characterised using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) by our group. The chromatographic fingerprint confirmed the presence of major bioactive constituents. The GC-MS spectra were reproducible across replicate analyses, validating batch-to-batch consistency and qualitative standardisation of the extract. Aliquots from this analytically characterised batch were used in this study to ensure experimental reproducibility.

This study was conducted using adult male Wistar rats (total 35) aged 7 weeks and weighing 150-200 g. To avoid hormonal fluctuations caused by the oestrus cycle in females that alter glucose metabolism, oxidative stress markers, and pain perception thresholds, male rats were exclusively selected. This approach ensured experimental consistency across biochemical and behavioral parameters. Standard laboratory settings were employed to house the rats, which included a 12-hour light/dark cycle, a controlled temperature of 25 °C and unrestricted access to water and a standard pellet diet.

According to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development recommendations, the acute toxicity of PHE was examined using male Wistar rats weighing 130-140 g to determine the dose. Before the experiment, the animals were fasted for 6-8 hours. PHE was given via both intraperitoneal (i.p.) and oral routes at different dosages to assess safety. The LD50 was determined using the Miller and Tainter formula. PHE did not cause mortality even at a high dose of 2000 mg/kg orally, which is the route used for subsequent efficacy studies. Therefore, based on standard pharmacological conventions, 1/10th of the maximum non-lethal dose (200 mg/kg) was adopted as the effective working dose for this study[24]. Moreover, this dose aligns well with earlier reports confirming the biological efficacy of individual components, including C. longa, M. fragrans and C. colocynthis, in rodent models of diabetes[25,26]. Additionally, a preliminary pilot trial in our laboratory (100, 200, and 400 mg/kg) confirmed that 200 mg/kg consistently caused significant antihyperglycemic and behavioral improvements, with no observable signs of toxicity or stress responses, and was therefore selected for this study.

Blood glucose levels were measured in all animals before the administration of STZ. The animals whose blood glucose levels ranged from 70 to 100 mg/dL, as determined using the glucose oxidase-peroxidase method blood glucose diagnostic kit (Accurex®, India), were included in the study. STZ at a dose of 55 mg/kg was dissolved in citrate buffer and administered intraperitoneally to induce diabetes[27]. The blood glucose level was measured 72 hours after STZ administration. For DN investigation, animals with blood glucose levels > 250 mg/dL were classified as diabetic. Previous studies, as well as experimental trials from our laboratory, served as the basis for the dosages and treatment plans.

Following the induction of diabetes, five groups with an equal number of rats (n = 7) were established. Control (C) group: Administered single i.p. injection of citrate buffer only; diabetic (D) group: Received a single dose of STZ (55 mg/kg body weight; i.p.) and no treatment; D + PHE: Treated with PHE orally (200 mg/kg body weight) starting from the 1st week; C + PHE: Included as negative control and received only PHE orally (200 mg/kg body weight); D + Met group: Included as a positive control and treated with Met orally (300 mg/kg body weight) starting from the 1st week. The treatment regimen was followed for 8 weeks. Body weights were recorded at weeks 0 and 8 after STZ administration.

After 8 weeks, behavioral parameters were analysed using the acetone drop, hot plate, tail-flick and rotarod tests.

At the end of the experiment, the rats were anesthetized (e.g., ketamine 80 mg/kg + xylazine 10 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) and their hearts were punctured using a sterile 5 mL syringe fitted with a 21-gauge needle to extract blood. Approximately 4-5 mL of whole blood was withdrawn from each rat. As this was a terminal collection, no repeated blood draws were performed. The collected blood was used for biochemical analysis. After blood collection, the animals were euthanized using CO2 inhaler system available in the animal house facility. The sciatic nerve was excised and stored at

Acetone drop test: Acetone (100 μL) was applied to the plantar region of the right hind paw, and the chilling sensation was monitored for 1 minute[28].

Hot plate test: With a 10-second cut-off time, the right hind paw of the rat was placed on a hot plate and maintained at

Tail-flick test: A modified version of the protocol of D’Amour and Smith[29] was used to perform this test. The tail was immersed in a beaker containing water maintained at 65 °C ± 5 °C. Tail-flick latency was recorded to measure the temperature sensitivity of the rats. The prompt removal of the tail from the plantar device indicated the onset of neuropathic pain. A period of 10 seconds was set as the cut-off for this experiment.

Rotarod test: Before sacrificing the rats, the rotarod test was performed using the Omni Rotor (Omnitech Electronics, Inc., Columbus, OH, United States) to determine motor impairment, as described previously[30]. The equipment featured a revolving rod with a 75-mm diameter, divided into four compartments, allowing for the simultaneous testing of four animals. The time spent by each animal was recorded, with a 5-minute gap, for a maximum duration of 180 seconds for each trial throughout the three trials. The time from 0.1 seconds to the rat falling to the ground was automatically recorded by the device. The cut-off limit was set at 180 seconds, and the pace was maintained at 10 revolutions per minute. The mean time of the three trials for which the rat remained on the rotating rod was used to calculate the score.

Serum glucose concentration was estimated at the end of the study using the glucose oxidase-peroxidase method with a commercially available kit (Crest Biosystems, Goa, India). Serum insulin level was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Ultra-Sensitive Rat Insulin ELISA kit, Crystal Chem Inc., IL, United States). A diagnostic kit (ELK Biotech, Wuhan, China) was employed to perform the glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) analysis using the cation-exchange method.

TG, TC, LDL-C and HDL-C were part of the lipid profile assessed using enzymatic kits (Agappe Diagnostics Ltd., Kerala, India). Friedewald’s equation was used to calculate the concentrations of LDL-C and very LDL-C.

Estimation of LPO level: MDA, a product of LPO, was determined in the sciatic nerve homogenate to estimate LPO indirectly[31]. The procedure involved mixing 0.1 mL of the homogenate with 1.5 mL of thiobarbituric acid (0.8%), 0.2 mL of sodium dodecyl sulphate (8.1%) and 1.5 mL of acetic acid (20%, pH 3.5) and then incubating the mixture for 1 hour at 100 °C. After adding 1 mL of distilled water and 5 mL of n-butanol: Pyridine (15:1, v/v), the blend was centrifuged for 10 minutes at 3000 × g. Following the removal of the organic layer, the absorbance was measured at 532 nm using a Shimadzu UV-1900 spectrophotometer. With a molar extinction coefficient of 9.6 × 103 M-1·cm-1, the amount of MDA generated in each sample was represented as nmol of MDA produced h-1·mg-1 of protein.

Assay of GSH: 5,5’-dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) was used to estimate the total GSH content utilising the procedure of Gherghel et al[32].

Assay of GST activity: The approach of Habig and Jakoby[33] was used to calculate GST activity. The reaction mixture comprised 1.0 mmol/L 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene, 0.1 mL of post-mitochondrial supernatant (PMS) and 3.0 mL of 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The reading was taken at 340 nm using a Shimadzu UV-1900 spectrophotometer. The molar extinction value of 9.6 × 103 M-1·cm-1 was employed to calculate the activity, which is the number of 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene conjugates created/minute/mg.

Assay of SOD and CAT activity: SOD activity was assessed using a standard protocol[34]. For instance, pyrogallol (24 mmol/L in 10 mmol/L HCl) and Tris-HCl buffer (50 mmol/L, pH 8.5) (25 μL and 2.875 mL, respectively) were mixed with 0.1 mL of PMS (10%). The absorbance was read at 420 nm to calculate SOD activity, which was then represented in units of mg-1 protein. The quantity that prevented the oxidation of 50% pyrogallol was considered as one unit of the enzyme. The Claiborne method was used to measure the CAT activity[35]. The procedure involved adding 0.1 mL of PMS (10%) to 1.9 mL of phosphate buffer (0.05 M, pH 7.0) and 1 mL of hydrogen peroxide (0.019 M). The readings were obtained at 240 nm. A molar extinction coefficient of 43.6 M-1·cm-1 was then used to estimate CAT activity as nmol H2O2 consumed minute-1·mg-1 protein.

As directed by the manufacturer, IL-β and TNF-α levels were measured using a commercial ELISA kit (RayBiotech, GA, United States).

To elucidate the neuroprotective mechanisms, neuron-specific markers, including BDNF and NGF, were measured in the serum and the sciatic nerve tissue using a commercial ELISA kit (RayBiotech, GA, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Their levels in the sciatic nerve homogenates were normalized to total protein content and expressed as (pg/mg protein).

The liver, pancreas and sciatic nerve tissues were preserved in 10% buffered formalin for histopathological processing. The tissues were washed, enclosed in paraffin blocks, sliced into 3-4 μm-thick sections and stained with haematoxylin and eosin for histopathological examination. After mounting the tissue sections in DPX mountant and performing two 2-minute xylene washes, the slides were viewed and analysed under a bright-field microscope. For morphometric analysis, hepatic steatosis was assessed semi-quantitatively as a percentage of steatosis. Pancreatic islet counts and diameters were measured using the ImageJ software in five randomly selected 10 × fields per section. Sciatic nerve damage was graded blindly by the pathologist on a 0-3 scale (0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe), reflecting axonal and myelin alterations.

For analysis purposes, the statistical programme SPSS 23 was utilised. For multiple comparisons, the Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test was performed after analysis of variance, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Accordingly, the mean ± SEM was used to present the data.

GC-MS analysis of the PHE showed a characteristic chemical fingerprint consistent with our latest dataset[36]. The profile indicated the presence of bioactive constituents (e.g., tetradecanoic acid, myristic acid TMS derivative and phenolic derivatives) known for their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties. A representative GC-MS chromatogram and the list of major compounds, as shown in Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1, confirm the consistent and reproducible nature of the extract used in this study.

Experimental timeline is shown in Figure 1. At week 0, the body weights of different groups did not differ significantly (Table 1). By week 8, however, a significant loss of body weight was observed in the diabetic group, confirming diabetes-induced weight loss (from 185.6 ± 5.2 g to 155.6 ± 6.5 g; P < 0.05). In contrast, diabetic + PHE group rats exhibited a significant increase in body weight (from 188.4 ± 5.8 g to 220.7 ± 7.4 g; P < 0.05), indicating the potential ameliorating effect of PHE treatment. The diabetic + Met group also exhibited a slight increase in body weight (from 198.7 ± 4.5 g to 210.5 ± 5.8 g; P < 0.05). The body weight of the diabetic + PHE group increased by 41.84% compared with the untreated diabetic group, while that of diabetic + Met animals increased by 35.28%. Interestingly, the control and control + PHE groups exhibited normal physiological weight gain, confirming that PHE is non-toxic to non-diabetic animals.

The rats with STZ-induced diabetes developed DN, which was confirmed by behavioral studies.

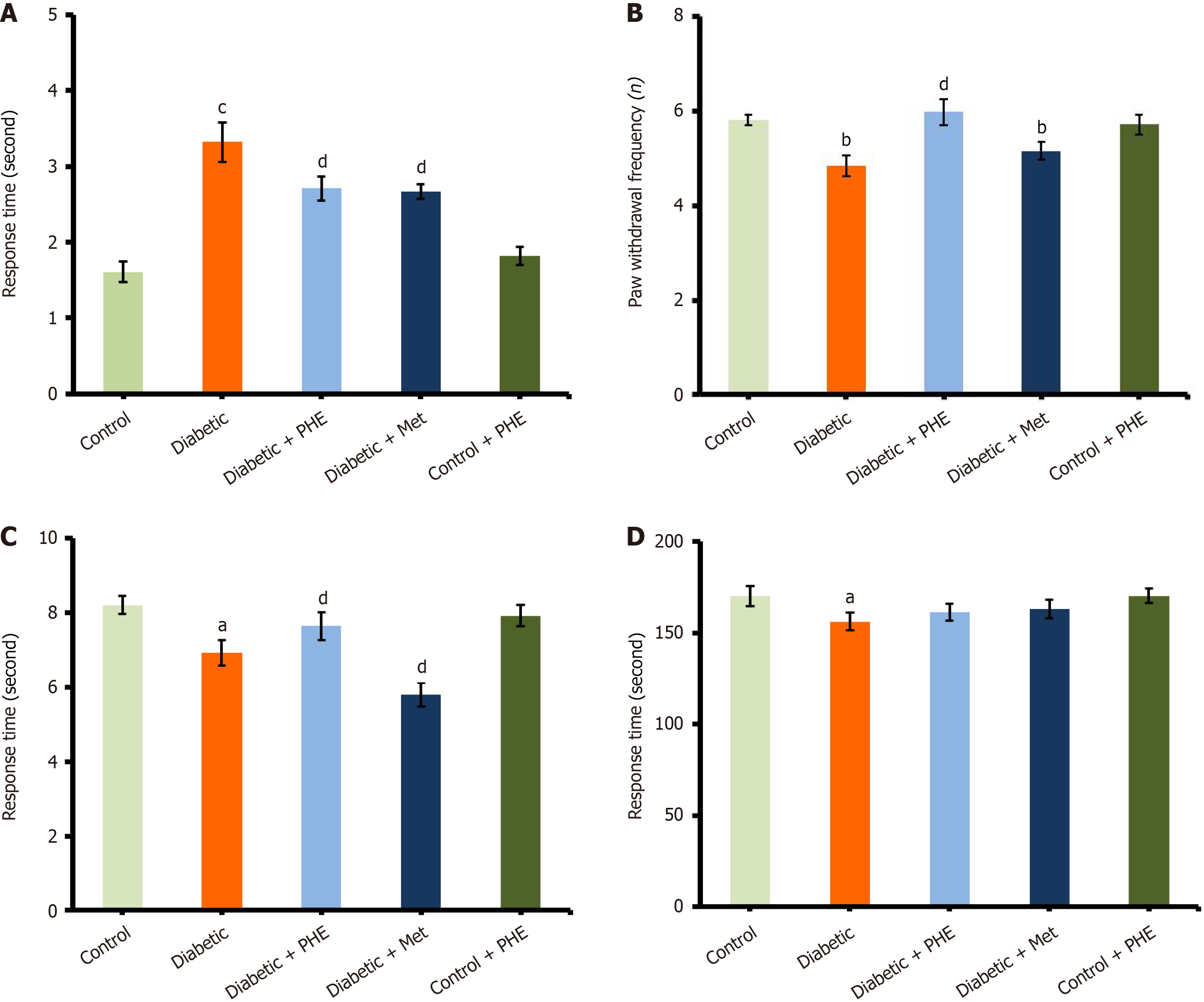

The diabetic rats exhibited a significant increase in withdrawal responses (3.32 ± 0.26 seconds) compared with the control group (1.61 ± 0.14 seconds), indicating that they had developed sensitivity to cold stimuli as a result of neuropathic pain. Nonetheless, PHE treatment reversed the cold-induced nociceptive behavior in diabetic rats (2.71 ± 0.16 seconds, P < 0.05 vs diabetic), signifying a moderate yet statistically significant analgesic action. A similar response was observed with the control drug Met (2.67 ± 0.10 seconds; P < 0.05 vs diabetic), a well-known anti-diabetic drug with neuroprotective properties (Figure 2A). Control + PHE (1.82 ± 0.12 seconds) did not significantly differ from the untreated control, confirming that PHE does not evoke an adverse sensory response in healthy animals.

This test was performed to determine the thermal nociceptive threshold, which indicates the sensory function and pain perception often impaired in DN. Latency to nociceptive response was markedly reduced in diabetic rats (4.85 ± 0.22 seconds) compared with the control group (5.81 ± 0.12 seconds; P < 0.01), demonstrating enhanced sensitivity to thermal stimuli and nerve dysfunction induced by diabetes (Figure 2B). Nevertheless, PHE application significantly increased the pain threshold in diabetic animals, with an increase in latency to 5.98 ± 0.27 seconds (P < 0.05 vs diabetic), thus indicating substantial recovery of sensory function. This effect was comparable and possibly slightly higher to that of the Met-treated diabetic group (5.16 ± 0.18 seconds; P < 0.05 vs diabetic), which approached normal values. The control + PHE group (5.72 ± 0.21 seconds) and the untreated control group did not vary significantly, demonstrating that PHE does not interfere with normal pain perception and thereby asserting its safety in non-diabetic animals.

This test evaluated spinal reflex nociceptive responses induced by nociception, indicating the integrity of peripheral and spinal sensory pathways. Diabetic rats displayed a significant decrease in response latency (6.93 ± 0.34 seconds) compared with the control (8.21 ± 0.25 seconds; P < 0.05), with severe thermal hyperalgesia and sensory function deficits that are typical of DN. However, treatment with PHE elevated the tail-flick latency to 7.64 ± 0.38 seconds and exerted a clear protective effect on pain thresholds and spinal reflex pathways (Figure 2C). The control + PHE group (7.92 ± 0.29 seconds) exhibited response latencies within the range of the untreated control group, confirming that PHE did not adversely affect normal nociceptive responses.

The rotarod test assessed motor coordination and balance, functions often compromised during DN. The major finding was that the diabetic rats fell significantly earlier than those in the control group (latency to fall: 156.25 ± 4.8 seconds vs 170.15 ± 5.6 seconds; P < 0.05), indicating disruptions in neuromuscular activity and coordination. However, treatment with PHE enhanced motor performance, with diabetic rats achieving a latency of 161.45 ± 4.7 seconds, establishing the protective effect of the extract on neuromuscular integrity. This performance compared favorably with that of Met-treated diabetic rats (163.15 ± 5.2 seconds), which also demonstrated improved motor function (Figure 2D). The control + PHE group maintained latency times (170.25 ± 3.9 seconds) similar to those of untreated control animals, implying that the extract does not impair normal motor activity.

At the end of 8 weeks, the diabetic group exhibited considerably elevated blood glucose levels (284.4 ± 5.1 mg/dL), confirming hyperglycaemia. Nonetheless, PHE treatment significantly reduced blood glucose levels in the diabetic animals, as indicated by the following comparison: Diabetic + PHE: 198.6 ± 4.9 mg/dL; P < 0.05 vs the diabetic group. A decrease in blood glucose level was observed in the diabetic + Met group (168.3 ± 4.1 mg/dL; P < 0.05) owing to the well-known hypoglycaemic action of the drug. PHE treatment lowered the fasting blood glucose (FBG) level by 30.17% and Met by 40.82% relative to the diabetic group. The control + PHE group exhibited only a slight increase (23.96%) compared with the control group, providing additional evidence for the safety of the extract. Induction of diabetes resulted in lower serum insulin levels (P < 0.05 vs control), indicative of beta-cell dysfunction. Both the Met and PHE groups demonstrated significantly increased insulin levels compared with the diabetic group. The PHE group exhibited a greater increase in insulin levels, suggesting the protective or stimulatory effect of the extract on pancreatic β-cell function. The control + PHE group did not display any substantial deviations from the control group. Concentrations of HbA1c increased substantially in the diabetic rats (P < 0.05 vs control) owing to prolonged exposure to hyperglycaemia. However, treatment with both PHE and Met significantly decreased HbA1c levels (P < 0.05 vs diabetic), with PHE and Met achieving reductions of 18.99% and 25.32% respectively. The control + PHE group displayed normal HbA1c levels, with only a 4.08% increase compared with the control group (Table 2).

| Groups1 | Blood glucose (mg/dL) | Insulin (ng/mL) | Haemoglobin (%) |

| Control | 96.4 ± 3.6 | 3.8 ± 0.65 | 4.9 ± 0.61 |

| Diabetic | 284.4 ± 5.1a (+195.02%) | 0.68 ± 0.36a (-82.11%) | 7.9 ± 0.52a (+61.22%) |

| Diabetic + PHE | 198.6 ± 4.9d (-30.17%) | 2.8 ± 0.46d (+311.76%) | 6.4 ± 0.71d (-18.99%) |

| Diabetic + Met | 168.3 ± 4.1d (-40.82%) | 3.1 ± 0.69d (+355.88%) | 5.9 ± 0.41d (-25.32%) |

| Control + PHE | 119.5 ± 4.6 (+23.96%) | 3.4 ± 0.67 (-10.53 %) | 5.1 ± 0.56 (+4.08%) |

Diabetic rats exhibited significant dyslipidaemia in the form of increased TC, TG and LDL-C and decreased HDL-C (P < 0.01 to P < 0.001, compared with the control) levels. However, both Met and PHE treatment rectified these abnormalities. PHE significantly reduced TC, TG and LDL-C levels (P < 0.05 to P < 0.01) and increased HDL-C levels (P < 0.01 compared with the diabetic group). These effects indicate that PHE modulates lipid levels favorably under diabetic conditions (Table 3).

| Groups/parameters1 | Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | Triglycerides (mg/dL) | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL) | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL) | Very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL) |

| Control | 125.33 ± 3.2 | 98.57 ± 4.3 | 58.62 ± 1.9 | 47.0 ± 2.3 | 19.71 ± 1.8 |

| Diabetic | 288.75 ± 4.7c (+130.39%) | 187.05 ± 5.3b (+89.776%) | 27.34 ± 1.6b (-53.36%) | 224.0 ± 4.6c (+376.59%) | 37.41 ± 1.9b (+89.80%) |

| Diabetic + PHE | 178.44 ± 3.9e (-38.20%) | 158.34 ± 5.2d (-15.35%) | 42.33 ± 2.4e (+54.83%) | 104.4 ± 3.8e (-53.39%) | 31.67 ± 1.6d (-15.34%) |

| Diabetic + Met | 148.42 ± 4.2f (-48.59%) | 139.22 ± 4.9d (-25.57%) | 48.78 ± 2.9e (+78.42%) | 71.8 ± 3.2f (-67.95%) | 27.84 ± 1.7d (-25.58%) |

| Control + PHE | 130.65 ± 3.3 (+4.24%) | 119.76 ± 4.4 (+21.49%) | 52.65 ± 3.1 (-10.18%) | 54.1 ± 3.1 (+15.11%) | 23.92 ± 2.1 (+21.36%) |

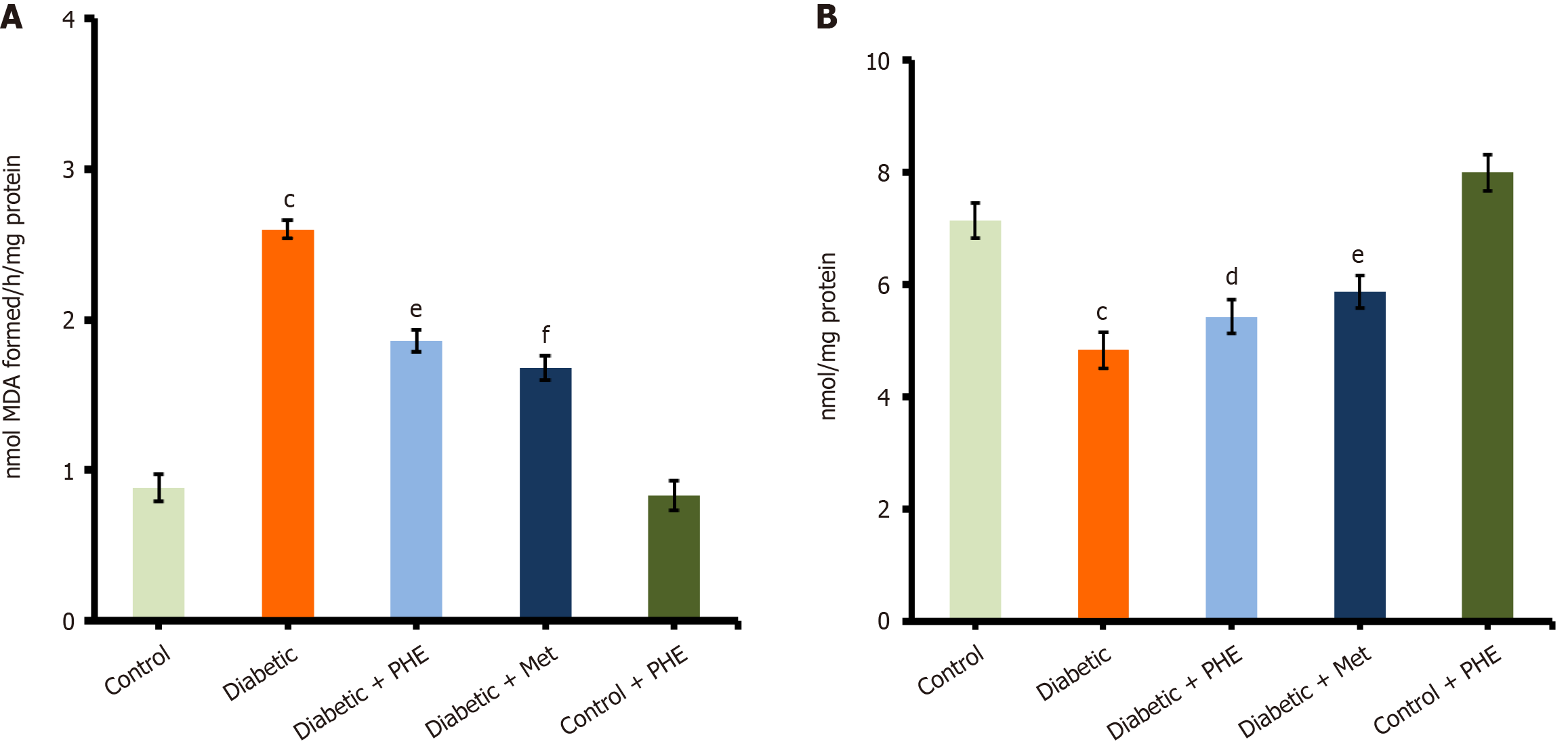

MDA is a well-known biomarker of LPO and oxidative stress. The diabetic group showed a significant increase in MDA levels (2.6 ± 0.06 nmol/mg protein) compared with the control group (0.88 ± 0.09 nmol/mg protein; P < 0.001), possibly reflecting an increased level of oxidative stress resulting from metabolic disorders associated with diabetes. Treatment with PHE significantly reduced the MDA levels in diabetic rats to 1.86 ± 0.07 nmol/mg protein (P < 0.01 vs the diabetic group), suggesting a strong antioxidant and free-radical scavenging activity (Figure 3A). Diabetic rats treated with Met exhibited more profound reductions in MDA levels (1.68 ± 0.08 nmol/mg protein; P < 0.001 vs the diabetic group), suggesting a significant mitigation of oxidative stress. The control + PHE group (0.83 ± 0.10 nmol/mg protein) exhibited MDA levels similar to those of the untreated control, indicating that PHE does not increase LPO under normal physiological conditions. GSH is a major intracellular antioxidant that protects cells from oxidative damage. A marked depletion of GSH levels was observed in the diabetic group (4.83 ± 0.32 μmol/mg protein) compared with the control group (7.14 ± 0.31 μmol/mg protein; P < 0.001). Nonetheless, treatment with PHE moderately restored GSH levels to 5.42 ± 0.30 μmol/mg protein (P < 0.05 vs the diabetic group) in diabetic rats, indicating partial restoration of antioxidant capacity (Figure 3B). The Met-treated diabetic group showed a slightly higher GSH level (5.88 ± 0.29 μmol/mg protein; P < 0.01 vs the diabetic group), indicating better restoration of the redox balance. The GSH levels in control + PHE rats (7.99 ± 0.33 μmol/mg protein) were almost the same as those in untreated controls, indicating that PHE administration, on its own, does not interfere with redox homeostasis under normal conditions.

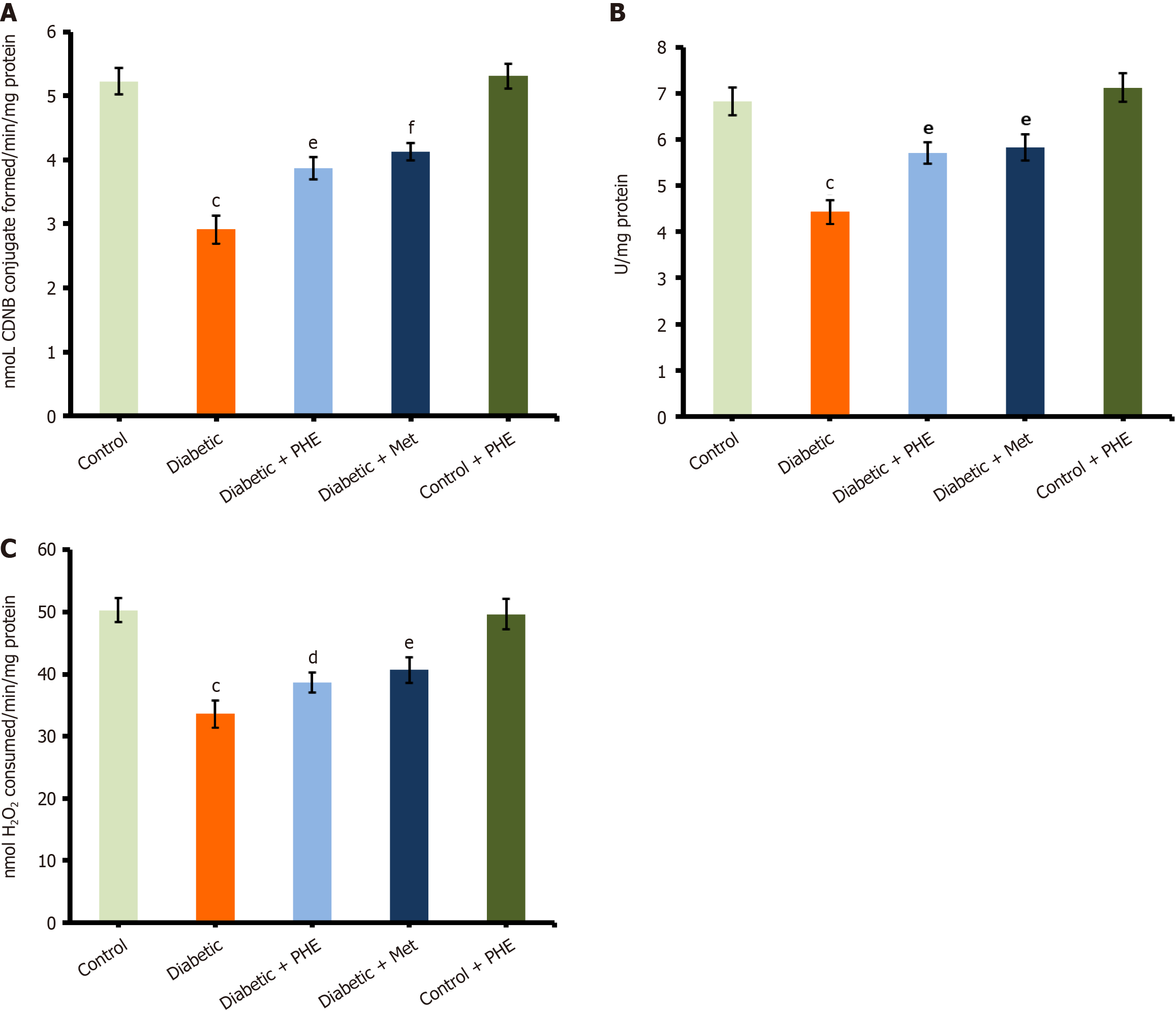

GST activity: GST plays a pivotal role in detoxification by conjugating GSH with toxic electrophilic compounds. In this study, the diabetic group exhibited significantly impaired GST activity (2.91 ± 0.22 U/mg protein) compared with the control (5.23 ± 0.21 U/mg protein; P < 0.001), reflecting reduced enzymatic antioxidant defence under hyperglycaemic conditions. Treatment with PHE significantly increased the GST to 3.87 ± 0.17 U/mg protein (P < 0.01 vs the diabetic group), indicating the restoration of antioxidant enzyme function. Slightly higher GST activity (4.13 ± 0.14 U/mg protein) was observed in Met-treated diabetic groups compared with PHE (P < 0.001 vs diabetic), confirming the effectiveness of standard anti-diabetic treatment in restoring enzymatic antioxidant capacity (Figure 4A). In the control + PHE group, GST levels (5.31 ± 0.19 U/mg protein) were similar to those in the untreated control, suggesting that PHE plays a non-toxic and possibly supportive role under physiological conditions.

SOD and CAT activities: SOD is a major antioxidant enzyme that scavenges superoxide radicals, thereby protecting cells from oxidative injury. The SOD activity was significantly reduced in diabetic animals (4.43 ± 0.26 U/mg protein) compared with the control (6.82 ± 0.30 U/mg protein; P < 0.001), indicating impaired enzymatic defence against oxidative stress. Treatment with PHE significantly increased the SOD activity in diabetic rats to 5.71 ± 0.23 U/mg protein (P < 0.01 vs diabetic), indicating partial restoration of the antioxidant enzyme function (Figure 4B). The Met-treated diabetic group exhibited slightly higher levels of SOD (5.83 ± 0.29 U/mg protein) than the PHE-treated group (P < 0.01 vs the diabetic group), asserting the role of the drug in the effective recovery of redox homeostasis. The SOD activity of the control + PHE group was similar to that of untreated control rats (7.12 ± 0.31 U/mg protein), indicating that the extract does not disrupt normal antioxidant enzyme function on its own but may assist in maintaining redox balance.

The CAT activity was significantly reduced under diabetic conditions compared with control conditions (diabetic: 33.6 ± 2.2 U/mg protein; 50.3 ± 1.9 U/mg protein; P < 0.001). Nonetheless, treatment with PHE significantly increased CAT levels (38.65 ± 1.6 U/mg protein; P < 0.05). The restoration of CAT activity was more pronounced in the case of Met treatment (40.66 ± 2.1 U/mg protein; P < 0.01), with values approaching normal levels. The control + PHE group (49.67 ± 2.5 U/mg protein) did not differ from the control group, signifying that PHE does not alter CAT activity under non-diabetic conditions (Figure 4C).

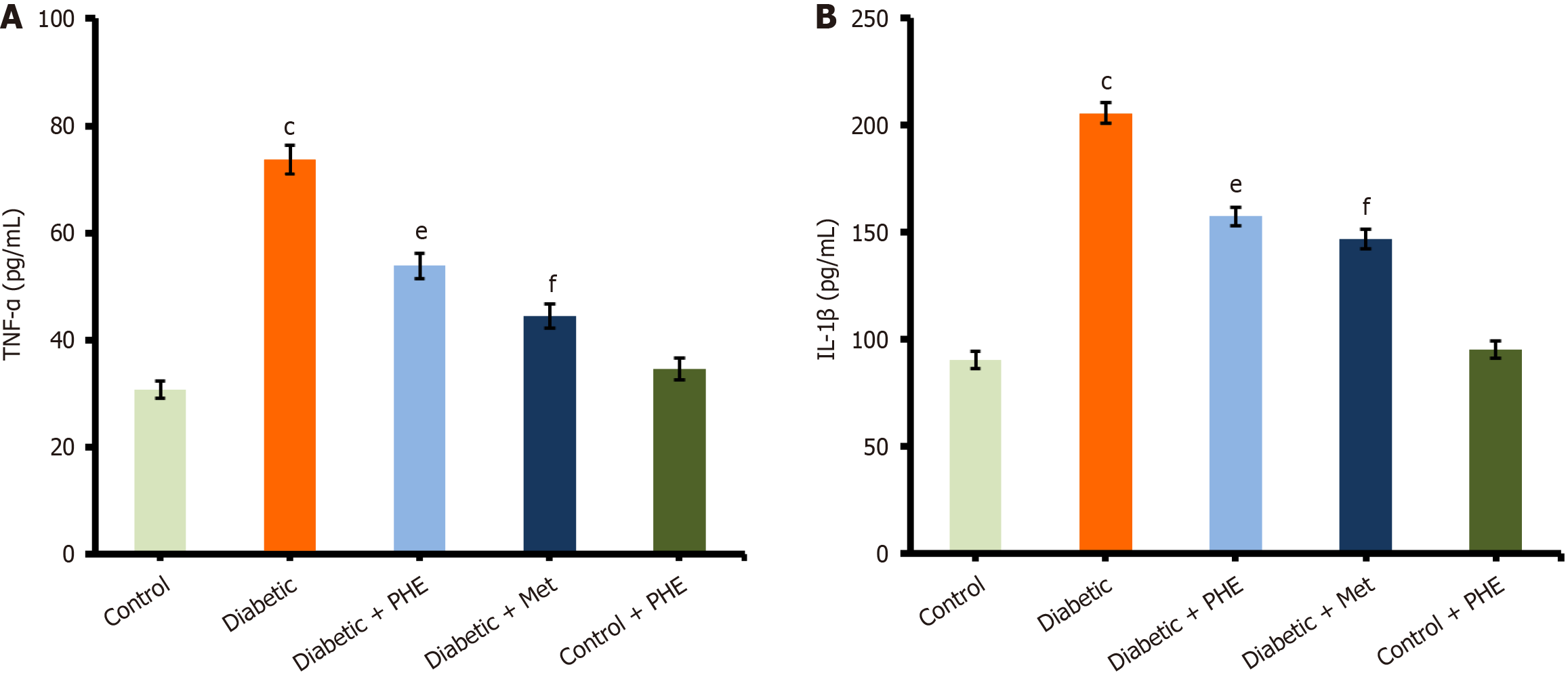

Compared with the control group (TNF-α = 30.67 ± 1.6 pg/mL), the level of TNF-α was significantly increased in the diabetic group (73.66 ± 2.7 pg/mL), indicating generalised inflammation due to hyperglycaemia. However, the administration of PHE resulted in a marked decrease in TNF-α levels (53.84 ± 2.4 pg/mL), signifying its anti-inflammatory effect (Figure 5A). Furthermore, similar reductions were observed in TNF-α levels in Met-treated diabetic rats (44.37 ± 2.3 pg/mL), confirming its anti-inflammatory activity. The control + PHE group (34.58 ± 2.1 pg/mL) did not differ significantly from the control group, implying that PHE does not promote inflammation in non-diabetic rats. Moreover, IL-1β level was significantly elevated in diabetic animals (205.66 ± 4.8 pg/mL) compared with the control group (90.54 ± 3.9 pg/mL, P < 0.001), showing a strong inflammatory response associated with the pathology of diabetes. Nonetheless, PHE treatment led to a significant decrease in the IL-1β level in diabetic animals (157.43 ± 4.4 pg/mL, P < 0.01 vs the diabetic group), suggesting a potent anti-inflammatory effect. Met also decreased the IL-1β level in the Met-administered group (146.87 ± 4.7 pg/mL, P < 0.001 vs diabetic), which agrees with its well-established anti-inflammatory function. The control + PHE group (95.33 ± 4.1 pg/mL) did not vary significantly from the control group, confirming that PHE does not alter the IL-1β level under normoglycemic conditions (Figure 5B).

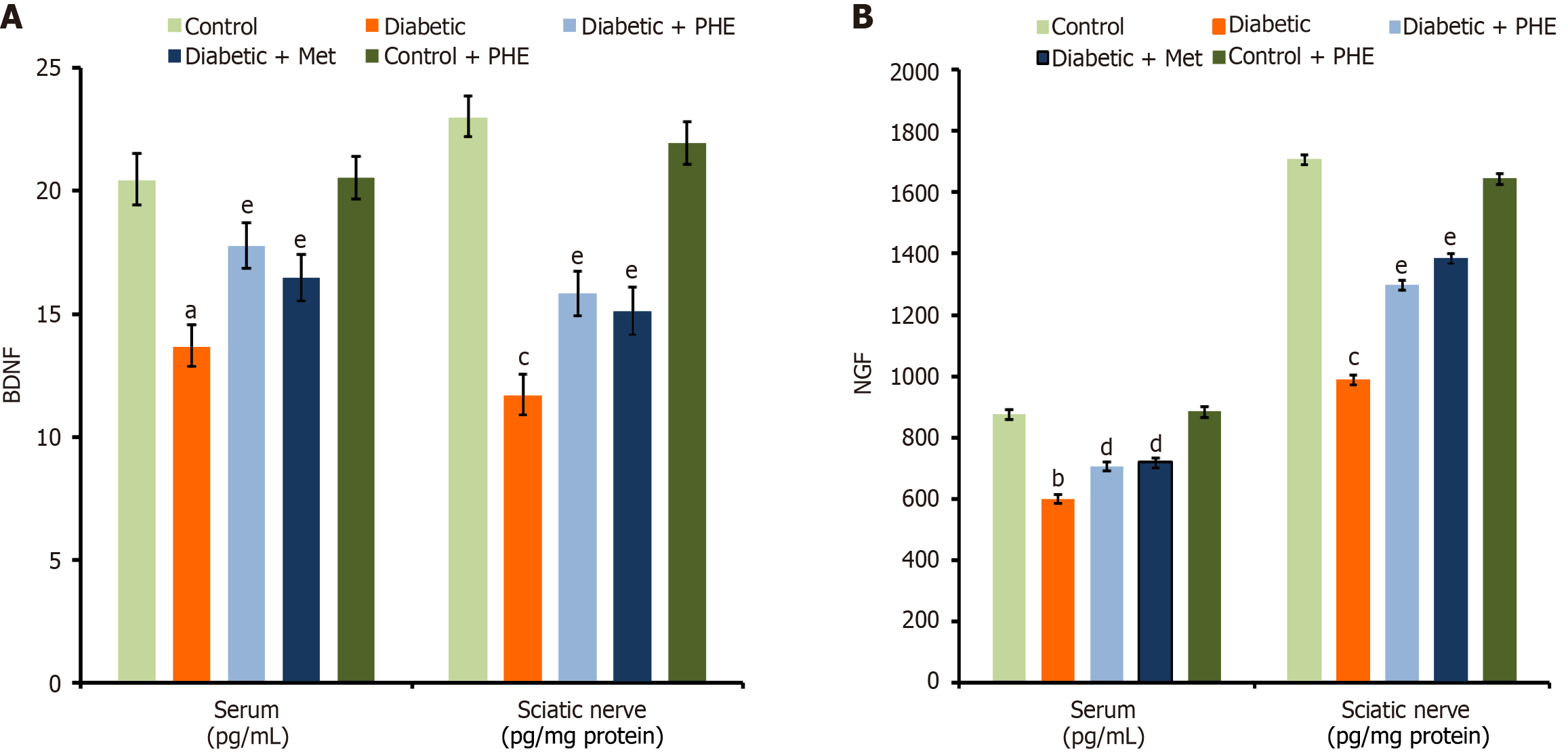

Diabetic rats exhibited significantly lower levels of BDNF in both the serum and the sciatic nerve (13.65 ± 0.9 pg/mL and 11.66 ± 0.78 pg/mg protein, respectively) compared with the control rats (20.43 ± 1.1 pg/mL in the serum and 22.98 ± 0.99 pg/mg protein in the sciatic nerve), indicating diabetes-induced neural impairment (P < 0.001). Nevertheless, PHE administration significantly improved the BDNF levels in both the serum and the sciatic nerve (17.78 ± 0.91 pg/mL and 15.84 ± 0.86 pg/mg protein, respectively), demonstrating a partial protective effect (P < 0.01 vs the diabetic group; Figure 6A). Treatment with Met also significantly restored the level of this biomarker in both the serum and the sciatic nerve (16.46 ± 0.95 pg/mL and 15.12 ± 0.89 pg/mg protein, respectively) (P < 0.01 vs the diabetic group), supporting its efficacy. Moreover, the levels in the control + PHE group (20.53 ± 0.87 pg/mL in the serum and 21.96 ± 0.91 pg/mg protein in the sciatic nerve) did not differ significantly compared with the control group (P < 0.05), proving that PHE does not alter the levels of this biomarker in healthy animals. In addition, the levels of NGF were diminished in diabetic rats in both the serum and the sciatic nerve (600.16 ± 13.99 pg/mL and 987.86 ± 15.33 pg/mg protein, respectively) compared with the control group (876.76 ± 12.87 pg/mL and 1708.32 ± 18.21 pg/mg protein, respectively) suggesting oxidative or neurotrophic damage associated with diabetes (P < 0.01). However, treatment with PHE significantly increased the biomarker levels in both the serum and the sciatic nerve (706.65 ± 13.87 pg/mL and 1297.64 ± 15.92 pg/mg protein, respectively), demonstrating a significant restoration (P < 0.05 vs the diabetic group; Figure 6B). The control + PHE group did not show a significant variation from the control group (P < 0.05), suggesting that PHE does not affect baseline biomarker levels in non-diabetic animals.

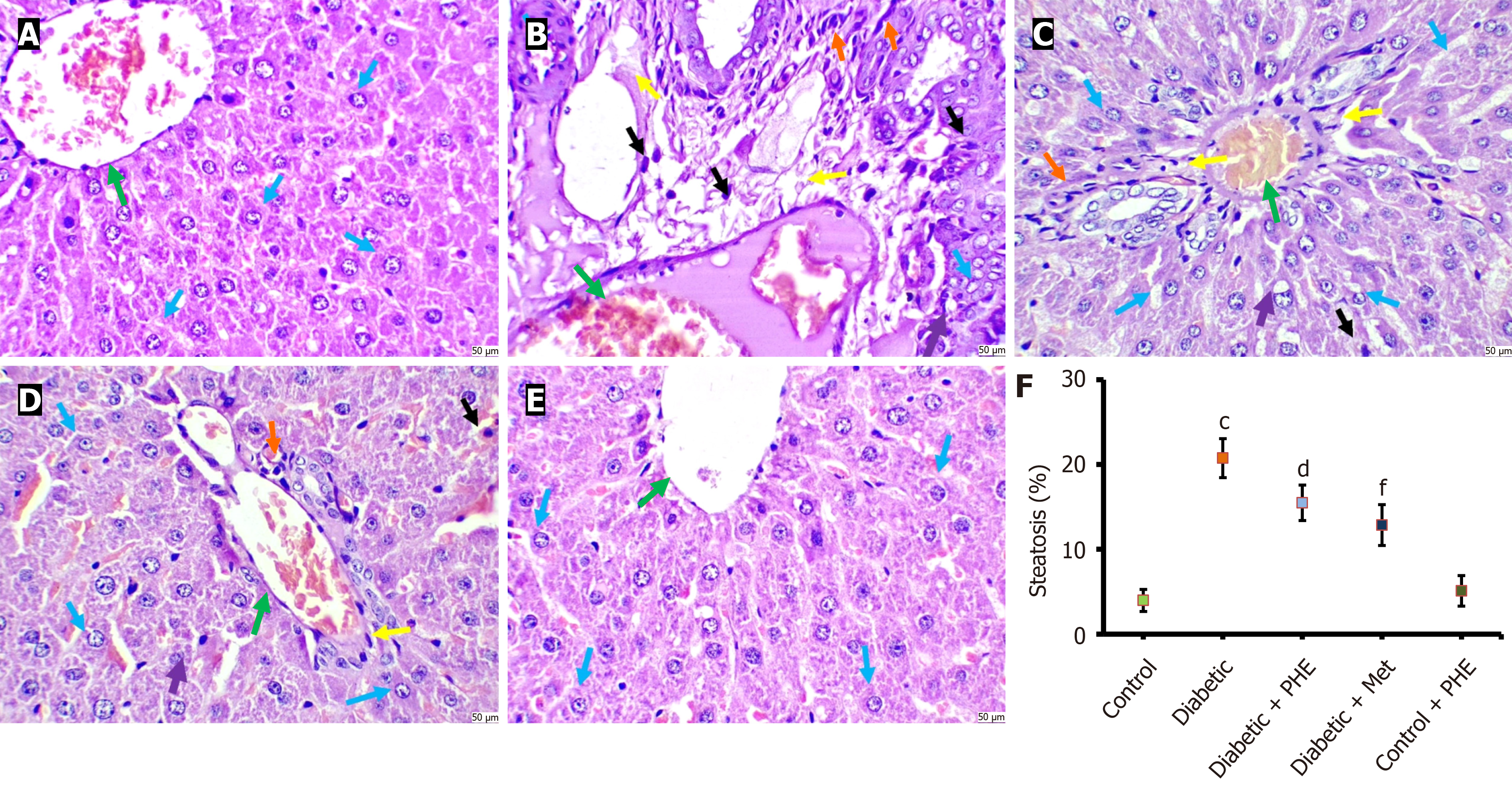

Histopathological examination of liver tissues from control animals revealed normal, trabecular-arranged hepatocytes with polygonal shapes, without any signs of cellular disintegration, pyknosis, apoptosis, or central vein congestion. The cytoplasm was clear, and normal/round/oval nuclei were noted. No inflammatory infiltrate or congestion was evident in the central vein. However, when sections from the diabetic group were studied, considerable hepatocyte damage was observed, characterised by high cellular density, dense cytoplasm and significant fatty changes, with a higher steatosis percentage (Figure 7) and vacuolation. Pyknosis and central vein congestion, along with inflammatory infiltrates, were seen. Sections from diabetic + PHE rats showed mild to moderate histological damage to the liver tissue. The hepatocytes were slightly damaged, with mild vacuolation and pyknosis. Moderate fatty changes and congestion were evident, accompanied by a decrease in steatosis percentage. Sections from diabetic + Met animals indicated normal hepatocytes. Mild histological damage to liver tissues was noted, with minimal alterations in characteristics such as congestion, fatty changes, vacuolation, pyknosis and inflammatory infiltrates. The sections from control + PHE rats exhibited a normal histological appearance (Figure 7).

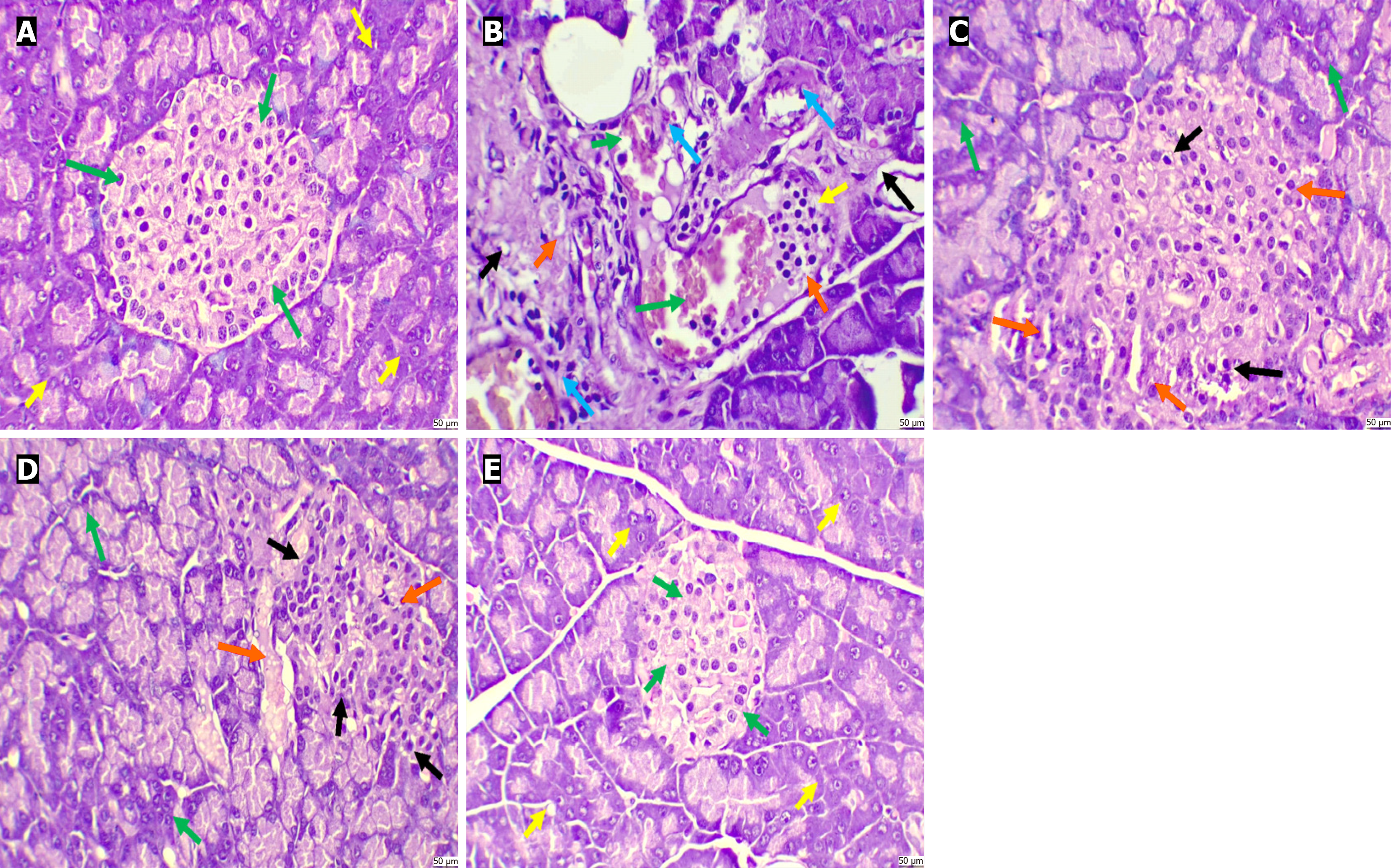

The haematoxylin and eosin-stained sections from the control group showed normal histological attributes of the pancreatic tissue. The islets of Langerhans appeared normal, with no evidence of cellular disintegration or atrophy. Furthermore, normal pyramidal acidophilic pancreatic acini were seen, with no congestion or haemorrhage. The diabetic group demonstrated considerable distortions in the pancreatic lobules and cellular disintegration in the islets of Langerhans, along with haemorrhage. Marked pyknosis was observed in the beta cells, and the pancreatic acini were atrophic, exhibiting substantial disintegration and fibrotic changes. The diabetic + PHE group displayed moderately damaged pancreatic lobules, characterised by cellular disintegration in the islets of Langerhans. Mild pyknosis was seen in the beta cells. The diabetic + Met group showed mild to moderate damage to pancreatic lobules and cellular disintegration in the islets of Langerhans. Moderate pyknosis was seen in the beta cells, with no congestion or haemorrhage. The control + PHE group presented normal histological attributes of the pancreatic tissue (Figure 8).

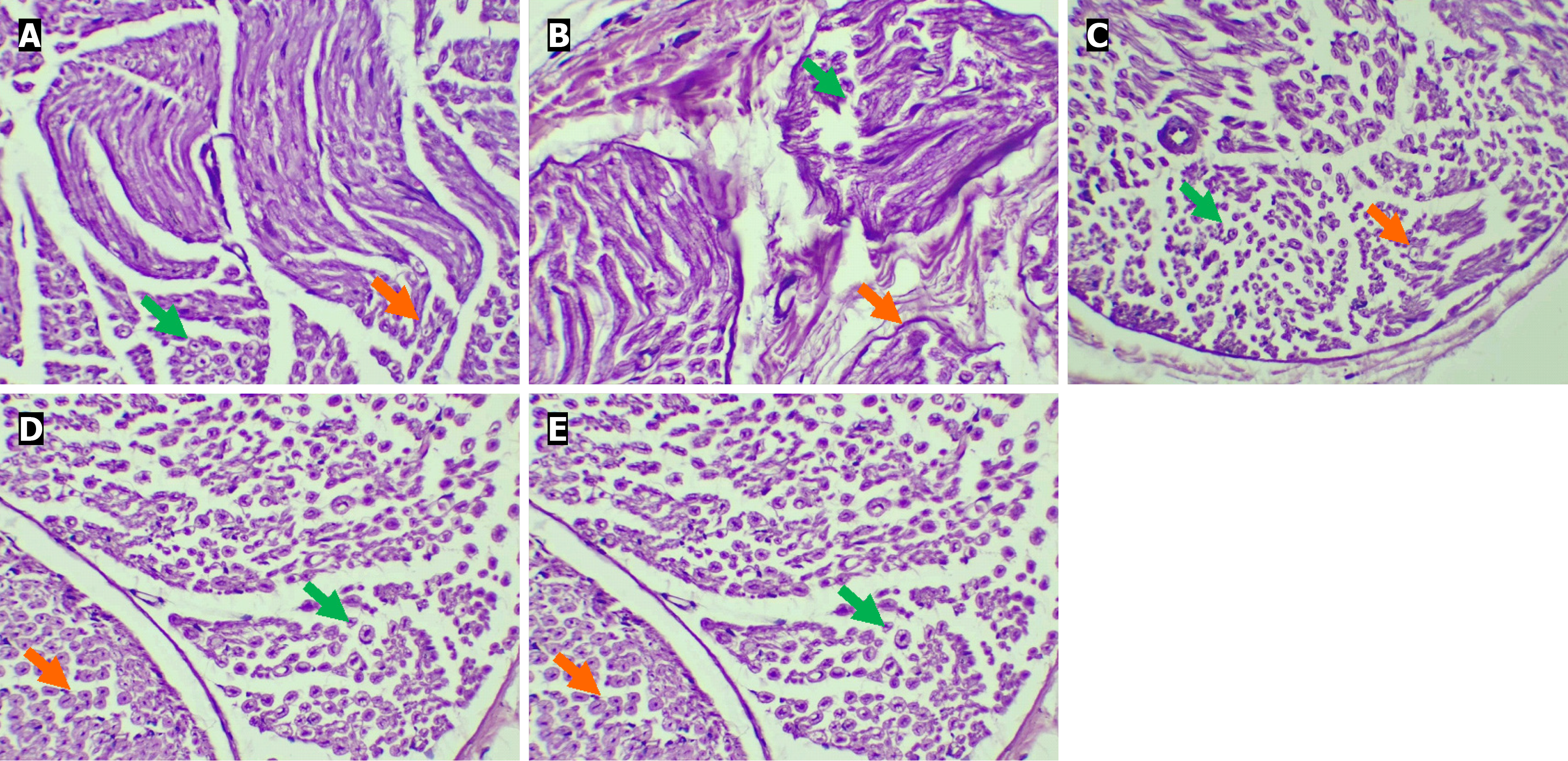

Sections from the control group possessed normal histopathological attributes of the sciatic nerve. Healthy or intact perineural sheath and intact epineurium were seen, along with healthy and intact axon and myelin sheath. The sections from the diabetic group exhibited significantly damaged histopathological attributes of the sciatic nerve. Severely damaged paraneural sheath, with highly affected sub-paraneural compartment and epineurium, was seen. At high power, significantly damaged and distorted axons and myelin sheaths were observed. The diabetic + PHE group exhibited mildly damaged and distorted features and myelin sheath. The diabetic + Met group showed mildly damaged histopathological attributes of the sciatic nerve and myelin sheath. Sections from the control + PHE group displayed healthy and intact axons and myelin sheaths (Figure 9). Semi-quantitative evaluation corroborated the qualitative histopathological observations. As shown in Table 4, diabetic rats exhibited a significant reduction in islet number and diameter, along with higher sciatic nerve lesion scores, which were ameliorated by PHE and Met treatments (P < 0.05).

| Groups | Number of islets, 10 × field | Diameter of the islet | Sciatic nerve damage score |

| Control | 6.33 ± 0.29 | 163.62 ± 12.71 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| Diabetic | 3.7 ± 0.32a | 95.83 ± 5.10a | 2.85 ± 0.16a |

| Diabetic+ PHE | 4.6 ± 0.42d | 145.81 ± 6.32d | 1.62 ± 0.23d |

| Diabetic + Met | 4.9 ± 0.52d | 140.22 ± 6.72d | 1.59 ± 0.24d |

| Control + PHE | 5.89 ± 0.37 | 156.47 ± 8.90 | 0.12 ± 0.02 |

This study was aimed at evaluating the activity of PHE, which comprised C. longa, M. fragrans and C. colocynthis, for the amelioration of DN in STZ-induced Wistar rats. DN is a common complication of DM that inflicts organ damage owing to inflammation, oxidative stress and neuronal injury. Existing pharmacological options are limited, offer little success and are associated with severe side effects. Hence, better rehabilitation options are sought. In this study, PHE was hypothesised to ameliorate oxidative stress, inflammation and neuronal damage and improve behavioral and histopathological outcomes in DN.

Pain perception, locomotor activity and behavioral patterns in the PHE-treated rats were consistent with known reports on the individual components of PHE. C. longa, containing the bioactive compound curcumin, has long been used for its anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties. Previous studies have demonstrated curcumin’s ability to attenuate neuropathic pain in diabetic rats via its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties[6]. Moreover, the anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective activities of M. fragrans are well established. Earlier study[37] noted that nutmeg extract can significantly reduce nociceptive behavior in chronic pain models, possibly by inhibiting pro-inflammatory mediators such as cyclooxygenase-2 and TNF-α. Nutmeg has also been shown to enhance pain threshold levels in a DN clinical trial[38]. In addition, C. colocynthis has been reported to be beneficial in treating neuropathic pain. According to Ostovar et al[16], C. colocynthis extract decreased pain perception and increased motor activity in diabetic animals by modulating pain pathways and mitigating oxidative stress. The combined action of the three herbs may result in enhanced pain relief and improved motor function, which can be attributed to their synergistic effects on inflammation and oxidative stress.

Our study established that PHE exerts a profound metabolic regulatory effect on STZ-administered diabetic rat models. The pronounced decrease in FBG following PHE treatment suggests its potent anti-hyperglycaemic activity. The 30.17% drop in FBG compared with the diabetic group indicates promising potential for therapeutic efficacy, although it is slightly less than that of the reference standard Met. This glucose-lowering effect is potentially attributable to the bioactive constituents, which have been previously reported to enhance insulin-sensitising action, glucose uptake and preservation of β-cell integrity[17,39,40].

Serum insulin levels were significantly elevated in diabetic rats receiving PHE, signifying possible stimulation or preservation of pancreatic β-cells. This finding corroborates past reports stating that the active constituent from C. longa could prevent STZ-induced cell apoptosis and improve insulin secretion[41,42]. Similarly, M. fragrans has been shown to regenerate pancreatic activity in various experimental models owing to its insulinotropic effect[43]. In contrast, C. colocynthis has been proven to promote insulin release against insulin resistance by influencing the signalling pathways of its major precursors[44]. Collectively, the improved insulin profile, together with a reduction in HbA1c level (18.99% reduction), asserts the ability of PHE to mediate long-term glycaemic control, a hallmark aim when treating DN. HbA1c is an established measure of chronic hyperglycaemia, and its declining level is linked to a lowering of the risk for developing microvascular complications such as neuropathy[45].

Dyslipidaemia is known to contribute to neuronal injury in diabetes via augmented oxidative stress, altered endothelial function and inflammation[46]. Apart from its glucose-lowering activity, PHE was able to reduce the levels of serum lipids in diabetic rats. The marked reductions in TC, TG and LDL-C, along with an elevation in HDL-C, are all markers of potent dyslipidaemic activity. Moreover, PHE could provide neuroprotection on a secondary basis by diminishing metabolic stressors that mediate DN development via normalisation of the lipid parameters, consistent with previous studies[47].

Another important mechanism in DN is the increased generation of ROS, causing oxidative stress, which in turn leads to neuronal damage and dysfunction. Oxidative stress can also cause damage to lipids, proteins and DNA, ultimately leading to neuroinflammation and axonal degeneration. Our study demonstrated a significant attenuation of oxidative stress markers (MDA and GSH) and an increase in antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD, GST and CAT) in PHE-treated rats. The modulation of oxidative stress markers and the strengthening of the antioxidant status of rats observed in this research may be attributed to the efficacy of individual herbs in mitigating oxidative injury, as demonstrated in previous studies[16,48-50].

Chronic inflammation serves as bedrock on which the condition of DN develops and progresses. The activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-1β) maintains the pluripotent inflammatory state that causes neuronal damage and death. In our study, PHE treatment significantly reduced the levels of inflammatory cytokines, confirming its strong anti-inflammatory potential attributed to the presence of phytoconstituents in individual components[51]. Curcumin, nutmeg and C. colocynthis reported from known literature interfere with the signalling pathways leading to inflammation, particularly by inhibiting the NF-κB pathway, the master regulator of inflammation[16,52,53]. Additionally, curcumin has been shown to inhibit the activation of inducible nitric oxide synthase, thereby reducing the production of nitric oxide, a key mediator of neuroinflammation. The observed anti-inflammatory response of PHE may involve possible contributions from bioactive constituents reported in these plants, although specific active agents within PHE remain to be investigated.

NGF and BDNF are well-defined neurotrophic factors that play a critical role in neuronal survival, differentiation and synaptic plasticity. Particularly, their expression is of immense significance in peripheral nerve regeneration and in thwarting neuronal damage under pathological conditions such as DN[54,55]. In this study, a significant reduction was observed in NGF and BDNF levels in DN rats, which corresponded with earlier reports showing that chronic hyperglycaemia down-regulates neurotrophic support and accelerates neuronal degeneration[11]. Restoration of neurotrophic factors is likely due to the bioactive constituents reported in C. longa, M. fragrans and C. colocynthis, which exert neuroprotective effects via antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and mitochondria-supportive pathways[56-58]. For instance, curcumin, among other phytochemicals, has been reported to up-regulate BDNF and NGF expression in various models of neurological damage and to enhance axonal regeneration and synaptic repair[19,59].

Nerve regeneration and myelination are crucial pathways in recovering from DN. The histopathological results obtained in this study demonstrated that PHE treatment significantly ameliorated nerve morphology, reduced axonal degeneration and enhanced myelination in treated rats. Curcumin has been shown to promote nerve regeneration in DN models by stimulating the phosphoinositide 3-kinases/protein kinase B pathway, which is involved in cell survival, proliferation and regeneration. Moreover, curcumin up-regulates the expression of neurotrophic factors such as BDNF[60] and promotes the activity of oligodendrocyte precursor cells while propelling the synthesis of myelin basic protein to enhance myelination[61]. Nutmeg possibly contributed to the improved histopathological outcomes noted in our study by stimulating myelination and nerve repair[23]. Extracts of C. colocynthis have been shown to enhance nerve repair by increasing the expression of NGFs and improving the morphology of nerve fibres[62]. The collective action of these constituents, as observed in previous literature, may be responsible for the improvements, although the exact molecular mechanism remains to be determined.

In addition to the in vivo behavioral, biochemical and histopathological assessments, our earlier work, involving GC-MS profiling and in silico docking studies, has provided reproducibility and key mechanistic insights into the therapeutic action of the examined PHE on DN. GC-MS profiling identified major compounds and ensured batch-to-batch chemical consistency. Absolute quantification of markers, such as curcumin, cucurbitacin B and myristicin, is planned for subsequent studies. Docking studies further revealed that aldose reductase (AR) interacts strongly with (4-isopropyl-1,6-dimethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene;1S,2R)-2-(4-allyl-2,6-dimethoxyphenoxy)-1-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-1-propanol; (S)-5-allyl-2-((1-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)propan-2-yl)oxy)-1,3-dimethoxybenzene and plays a vital role in the disability mechanism of DN[36]. The over-activation of AR causes the accumulation of sorbitol in nerve fibres, leading to oxidative stress and nerve damage. AR inhibition by these phytochemicals appears to be a crucial mechanism in attenuating oxidative and inflammatory damage[63]. This finding aligns with the in vivo results from the current investigation in which rats treated with PHE displayed decreased MDA levels, improved antioxidant markers and reduced levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, correlating with an improved behavioral outcome. This multi-system action, against oxidative stress, inflammation and AR activity, underscores the synergistic potential of PHE and finds an important translation into a multi-component therapeutic candidate against DN.

These results, although promising, have some limitations. The study was conducted exclusively in male rats to minimise hormonal variability; however, it is recognised that sex differences exist in oxidative stress and neuropathic progression, and female cohorts should be included in future studies to validate and extend the present findings. Furthermore, the pharmacokinetics of PHE and those of its components are worth exploring as a method to understand their bioavailability and optimal dosage for therapeutic use. Lastly, further studies are required to investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying the synergistic effects of these herbs, including signal transduction pathways (NF-κB, phosphoinositide 3-kinases/protein kinase B and AR pathways) that contribute to neuroinflammation and oxidative stress. Future studies would be conducted using targeted molecular techniques to address this issue.

To summarise, the PHE from C. longa, M. fragrans and C. colocynthis has significant therapeutic potential in alleviating certain behavioral, biochemical and histopathological features of DN in STZ-induced rats. Individual herbal components are known to exhibit antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects; however, the observed impacts most likely resulted from synergistic interactions in PHE. These findings support the use of PHE as a potential natural treatment for DN and, quite rightly, warrant clinical consideration for further research. Thus, this study provides additional evidence for the use of plant-based compounds and contributes to the existing knowledge on the integrative approach for managing chronic diabetic complications.

| 1. | Akbar S, Subhan F, Akbar A, Habib F, Shahbaz N, Ahmad A, Wadood A, Salman S. Targeting Anti-Inflammatory Pathways to Treat Diabetes-Induced Neuropathy by 6-Hydroxyflavanone. Nutrients. 2023;15:2552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Callaghan BC, Cheng HT, Stables CL, Smith AL, Feldman EL. Diabetic neuropathy: clinical manifestations and current treatments. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:521-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 612] [Cited by in RCA: 787] [Article Influence: 56.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Vincent AM, Callaghan BC, Smith AL, Feldman EL. Diabetic neuropathy: cellular mechanisms as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:573-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 325] [Cited by in RCA: 398] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Feldman EL, Nave KA, Jensen TS, Bennett DLH. New Horizons in Diabetic Neuropathy: Mechanisms, Bioenergetics, and Pain. Neuron. 2017;93:1296-1313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 572] [Cited by in RCA: 676] [Article Influence: 75.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sheethal S, Ratheesh M, Svenia P Jose, Sandya S. Effect of Glutathione Enriched Polyherbal Formulation on Streptozotocin Induced Diabetic Model by Regulating Oxidative Stress and PKC Pathway. Pharmacogn Res. 2023;15:347-355. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Kaur N, Kishore L, Farooq SA, Kajal A, Singh R, Agrawal R, Mannan A, Singh TG. Cucurbita pepo seeds improve peripheral neuropathy in diabetic rats by modulating the inflammation and oxidative stress in rats. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2023;30:85910-85919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Obrosova IG. Diabetes and the peripheral nerve. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1792:931-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pop-Busui R, Boulton AJ, Feldman EL, Bril V, Freeman R, Malik RA, Sosenko JM, Ziegler D. Diabetic Neuropathy: A Position Statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:136-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1426] [Cited by in RCA: 1586] [Article Influence: 176.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | Wiggin TD, Sullivan KA, Pop-Busui R, Amato A, Sima AA, Feldman EL. Elevated triglycerides correlate with progression of diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes. 2009;58:1634-1640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Anand P, Terenghi G, Warner G, Kopelman P, Williams-Chestnut RE, Sinicropi DV. The role of endogenous nerve growth factor in human diabetic neuropathy. Nat Med. 1996;2:703-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fernyhough P, Roy Chowdhury SK, Schmidt RE. Mitochondrial stress and the pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2010;5:39-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Moosaie F, Mohammadi S, Saghazadeh A, Dehghani Firouzabadi F, Rezaei N. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0268816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | He WL, Chang FX, Wang T, Sun BX, Chen RR, Zhao LP. Serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients and its association with cognitive impairment: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0297785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | K U VR, Siddiqi SS, Debbarman T, Mukherjee A, Akhtar N, Waris A, Thacker D, Shaista. Serum Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor: An Emerging Marker for Diabetic Retinopathy. Cureus. 2024;16:e74153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lakshmi SGVJ. Antidiabetic and Anti-neuropathic Activities of Hydroalcoholic Polyherbal Extract in Wistar Rats. Trop J Nat Prod Res. 2023;7:3881-3886. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Ostovar M, Akbari A, Anbardar MH, Iraji A, Salmanpour M, Hafez Ghoran S, Heydari M, Shams M. Effects of Citrullus colocynthis L. in a rat model of diabetic neuropathy. J Integr Med. 2020;18:59-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Aggarwal BB, Harikumar KB. Potential therapeutic effects of curcumin, the anti-inflammatory agent, against neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, pulmonary, metabolic, autoimmune and neoplastic diseases. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:40-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1440] [Cited by in RCA: 1262] [Article Influence: 74.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kumar S, Narwal S, Kumar V, Prakash O. α-glucosidase inhibitors from plants: A natural approach to treat diabetes. Pharmacogn Rev. 2011;5:19-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 427] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kandezi N, Mohammadi M, Ghaffari M, Gholami M, Motaghinejad M, Safari S. Novel Insight to Neuroprotective Potential of Curcumin: A Mechanistic Review of Possible Involvement of Mitochondrial Biogenesis and PI3/Akt/ GSK3 or PI3/Akt/CREB/BDNF Signaling Pathways. Int J Mol Cell Med. 2020;9:1-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sultan MT, Saeed F, Raza H, Ilyas A, Sadiq F, Musarrat A, Afzaal M, Hussain M, Raza MA, Al Jbawi E. Nutritional and therapeutic potential of nutmeg (Myristica fragrans): A concurrent review. Cogent Food Agric. 2023;9:2279701. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Veerendrakumar SP, Gayathri R, Priya VV, Selvaraj J, Kavitha S. Evaluation of Antioxidant and Protease-inhibitory Potential of Ethanolic Extract of Myristica fragrans (Nutmeg). J Pharm Res Int. 2021;33:263-270. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Al-Quraishy S, Dkhil MA, Abdel-Gaber R, Zrieq R, Hafez TA, Mubaraki MA, Abdel Moneim AE. Myristica fragrans seed extract reverses scopolamine-induced cortical injury via stimulation of HO-1 expression in male rats. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2020;27:12395-12404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ghorbanian D, Ghasemi-Kasman M, Hashemian M, Gorji E, Gol M, Feizi F, Kazemi S, Ashrafpour M, Moghadamnia AA. Myristica Fragrans Houtt Extract Attenuates Neuronal Loss and Glial Activation in Pentylenetetrazol-Induced Kindling Model. Iran J Pharm Res. 2019;18:812-825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chopra K. Fundamentals of experimental pharmacology. Indian J Pharmacol. 2020;52:443. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kalva S, Fatima N, Raghunandan N, Samreen S. Insulinomimetic Effect of Citrullus Colocynthis Roots in STZ Challenged Rat Model. Iran J Pharm Sci. 2018;14:49-66. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Rai PK, Jaiswal D, Mehta S, Rai DK, Sharma B, Watal G. Effect of Curcuma longa freeze dried rhizome powder with milk in STZ induced diabetic rats. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2010;25:175-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Morrow TJ. Animal models of painful diabetic neuropathy: the STZ rat model. Curr Protoc Neurosci. 2004;Chapter 9: Unit 9.18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Choi SJ, Lee I, Jang BH, Youn DY, Ryu WH, Park CO, Kim ID. Selective diagnosis of diabetes using Pt-functionalized WO3 hemitube networks as a sensing layer of acetone in exhaled breath. Anal Chem. 2013;85:1792-1796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | D’amour FE, Smith DL. A Method For Determining Loss of Pain Sensation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1941;72:74-79. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 30. | Andrabi SS, Parvez S, Tabassum H. Progesterone induces neuroprotection following reperfusion-promoted mitochondrial dysfunction after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Dis Model Mech. 2017;10:787-796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ohkawa H, Ohishi N, Yagi K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem. 1979;95:351-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17627] [Cited by in RCA: 19254] [Article Influence: 409.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Gherghel D, Griffiths HR, Hilton EJ, Cunliffe IA, Hosking SL. Systemic reduction in glutathione levels occurs in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:877-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Habig WH, Jakoby WB. Assays for differentiation of glutathione S-transferases. Methods Enzymol. 1981;77:398-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1597] [Cited by in RCA: 1701] [Article Influence: 37.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Marklund S, Marklund G. Involvement of the superoxide anion radical in the autoxidation of pyrogallol and a convenient assay for superoxide dismutase. Eur J Biochem. 1974;47:469-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6497] [Cited by in RCA: 6764] [Article Influence: 130.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Greenwald RA. Handbook of Methods for Oxygen Radical Research. 1st ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 1985: 467. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 36. | Kausar MA, Anwar S, Elagib HM, Parveen K, Hussain MA, Najm MZ, Nair A, Kar S. GC-MS Profiling of Ethanol-Extracted Polyherbal Compounds from Medicinal Plant (Citrullus colocynthis, Curcuma longa, and Myristica fragrans): In Silico and Analytical Insights into Diabetic Neuropathy Therapy via Targeting the Aldose Reductase. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2025;47:75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Zhang WK, Tao SS, Li TT, Li YS, Li XJ, Tang HB, Cong RH, Ma FL, Wan CJ. Nutmeg oil alleviates chronic inflammatory pain through inhibition of COX-2 expression and substance P release in vivo. Food Nutr Res. 2016;60:30849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Motilal S, Maharaj RG. Nutmeg extracts for painful diabetic neuropathy: a randomized, double-blind, controlled study. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19:347-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Larijani B, Abdollahi M. A review on the role of antioxidants in the management of diabetes and its complications. Biomed Pharmacother. 2005;59:365-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 510] [Cited by in RCA: 511] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Ghauri AO, Ahmad S, Rehman T. In vitro and in vivo anti-diabetic activity of Citrullus colocynthis pulpy flesh with seeds hydro-ethanolic extract. J Complement Integr Med. 2020;17:/j/jcim.2020.17.issue-2/jcim. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Arulmozhi DK, Kurian R, Veeranjaneyulu A, Bodhankar SL. Antidiabetic and Antihyperlipidemic Effects of Myristica fragrans. in Animal Models. Pharm Biol. 2007;45:64-68. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 42. | Jain SK, Rains J, Jones K. Effect of curcumin on protein glycosylation, lipid peroxidation, and oxygen radical generation in human red blood cells exposed to high glucose levels. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:92-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Broadhurst CL, Polansky MM, Anderson RA. Insulin-like biological activity of culinary and medicinal plant aqueous extracts in vitro. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:849-852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Huseini HF, Darvishzadeh F, Heshmat R, Jafariazar Z, Raza M, Larijani B. The clinical investigation of Citrullus colocynthis (L.) schrad fruit in treatment of Type II diabetic patients: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Phytother Res. 2009;23:1186-1189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet. 1998;352:837-853. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Vincent AM, Russell JW, Low P, Feldman EL. Oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:612-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 608] [Cited by in RCA: 628] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Opazo-Ríos L, Mas S, Marín-Royo G, Mezzano S, Gómez-Guerrero C, Moreno JA, Egido J. Lipotoxicity and Diabetic Nephropathy: Novel Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Opportunities. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:2632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 44.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Zhao WC, Zhang B, Liao MJ, Zhang WX, He WY, Wang HB, Yang CX. Curcumin ameliorated diabetic neuropathy partially by inhibition of NADPH oxidase mediating oxidative stress in the spinal cord. Neurosci Lett. 2014;560:81-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Patel SS, Acharya A, Ray RS, Agrawal R, Raghuwanshi R, Jain P. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of curcumin in prevention and treatment of disease. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2020;60:887-939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 44.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Pashapoor A, Mashhadyrafie S, Mortazavi P. Ameliorative effect of Myristica fragrans (nutmeg) extract on oxidative status and histology of pancreas in alloxan induced diabetic rats. Folia Morphol (Warsz). 2020;79:113-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Li Y, Zhang Y, Liu DB, Liu HY, Hou WG, Dong YS. Curcumin attenuates diabetic neuropathic pain by downregulating TNF-α in a rat model. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10:377-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Le TT, Tran SH, Lee S, Kang SW, Kim JH, Park K, Kim CS, Kim M, Kang K, Jung SH. Furan Acids from Nutmeg and Their Neuroprotective and Anti-neuroinflammatory Activities. J Agric Food Chem. 2025;73:11080-11093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Esmaealzadeh N, Miri MS, Mavaddat H, Peyrovinasab A, Ghasemi Zargar S, Sirous Kabiri S, Razavi SM, Abdolghaffari AH. The regulating effect of curcumin on NF-κB pathway in neurodegenerative diseases: a review of the underlying mechanisms. Inflammopharmacology. 2024;32:2125-2151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Terenghi G. Peripheral nerve regeneration and neurotrophic factors. J Anat. 1999;194 (Pt 1):1-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 471] [Cited by in RCA: 466] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 55. | Siniscalco D, Giordano C, Rossi F, Maione S, de Novellis V. Role of neurotrophins in neuropathic pain. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2011;9:523-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 56. | Al-Qahtani WH, Dinakarkumar Y, Arokiyaraj S, Saravanakumar V, Rajabathar JR, Arjun K, Gayathri PK, Nelson Appaturi J. Phyto-chemical and biological activity of Myristica fragrans, an ayurvedic medicinal plant in Southern India and its ingredient analysis. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2022;29:3815-3821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Kapoor M, Kaur N, Sharma C, Kaur G, Kaur R, Batra K, Rani J. Citrullus colocynthis an Important Plant in Indian Traditional System of Medicine. Pharmacogn Rev. 2021;14:22-27. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Sevindik M, Uysal I, Sevindik E, Krupodorova T, Koçer O, Ünal O. Citrullus colocynthis (Bitter-apple): a comprehensive review on general properties, biological activities, phenolic and chemical contents. Not Sci Biol. 2024;16:12202. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 59. | Zhang WX, Lin ZQ, Sun AL, Shi YY, Hong QX, Zhao GF. Curcumin Ameliorates the Experimental Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy through Promotion of NGF Expression in Rats. Chem Biodivers. 2022;19:e202200029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Zamanian MY, Alsaab HO, Golmohammadi M, Yumashev A, Jabba AM, Abid MK, Joshi A, Alawadi AH, Jafer NS, Kianifar F, Obakiro SB. NF-κB pathway as a molecular target for curcumin in diabetes mellitus treatment: Focusing on oxidative stress and inflammation. Cell Biochem Funct. 2024;42:e4030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Wang G, Wang Z, Gao S, Wang Y, Li Q. Curcumin enhances the proliferation and myelinization of Schwann cells through Runx2 to repair sciatic nerve injury. Neurosci Lett. 2022;770:136391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Cheng X, Qin M, Chen R, Jia Y, Zhu Q, Chen G, Wang A, Ling B, Rong W. Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad.: A Promising Pharmaceutical Resource for Multiple Diseases. Molecules. 2023;28:6221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Tang WH, Martin KA, Hwa J. Aldose reductase, oxidative stress, and diabetic mellitus. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/