Published online Mar 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i3.100245

Revised: November 4, 2024

Accepted: December 16, 2024

Published online: March 15, 2025

Processing time: 163 Days and 3.6 Hours

Several studies have suggested a close link between depression, overweight, and new-onset diabetes, particularly among middle-aged and older populations; how

To investigate the role of overweight in mediating the association between de

Data of 9426 individuals aged ≥ 50 years from the 1998-2016 Health and Re

New-onset diabetes was identified in 23.6% of the study population. Depression was significantly associated with new-onset diabetes (OR: 1.18, 95%CI: 1.03-1.35, P value: 0.014). Further adjustment for overweight attenuated the effect of depression on new-onset diabetes to 1.14 (95%CI: 1.00-1.30, P = 0.053), with a significant mediating effect (P of Sobel test = 0.003). The mediation analysis demonstrated that overweight accounted for 61% in depression for the risk of new-onset diabetes, with overweight having a partially mediating role in the depression-to-diabetes pathway.

New-onset diabetes was not necessarily a direct complication of depression; rather, depression led to behaviors that increase the risk of overweight and, consequently, new-onset diabetes.

Core Tip: Depression was positively associated with the risk of new-onset diabetes in middle-aged and older populations in the United States, and 61% of this process was mediated by overweight. This indicated that new-onset diabetes was not a direct complication of depression; rather, depressive states led to behaviors that increased the risk of overweight and, consequently, new-onset diabetes.

- Citation: Zhang ZH, Yue SY, Su M, Zhang HL, Wu QC, Li ZL, Zhang NJ, Hao ZY, Li M, Huang HJ, Ma J, Liu YY, Wang H. Overweight in mediating the association between depression and new-onset diabetes: A population-based research from Health and Retirement Study. World J Diabetes 2025; 16(3): 100245

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v16/i3/100245.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i3.100245

New-onset diabetes is a significant contributor to disability and mortality, and its prevalence has increased rapidly in recent years[1]. According to the World Health Organization, 529 million people worldwide had new-onset diabetes in 2021, and the overall global age-standardized prevalence was 6.1%[2]. New-onset diabetes can lead to fatigue in the short term and increase the risk of infections; moreover, it may lead to severe dehydration and ketoacidosis in severe cases[3]. Furthermore, new-onset diabetes can impair the filtering function of the kidneys and the cardiometabolic function of the heart, leading to diabetic nephropathy[4], coronary heart disease[5], and stroke[6]. Notably, new-onset diabetes usually leads to dementia in the middle-aged and older populations[7] and significantly impairs their quality of life. Therefore, a more comprehensive understanding of the pathophysiology of new-onset diabetes is crucial for its prevention in middle-aged and older individuals.

Depression is a mood disorder characterized by persistent low mood, diminished interest in activities, and variations in eating behaviors, including binge eating and appetite suppression[8]. Depression has emerged as a focal area of research in the diabetes domain, albeit with inconsistent findings. Some studies have indicated that depression may be a risk factor for new-onset diabetes[9,10]; in contrast, other studies report no direct association between depression and new-onset diabetes[11]. Notably, both anorexia-type and hyperphagia-type depression can lead to an increase in body mass index (BMI). An 18-year study on middle-aged Americans showed that emotional eating played a significant role in the development of depression and increased BMI[12]. Additionally, individuals with anorexia-type depression usually reduce their physical activity or avoid social interactions, which may lead to an increase in BMI[8]. Furthermore, high BMI is a significant risk factor for new-onset diabetes[13]. However, the exact role of BMI in the association between depression and new-onset diabetes remains unclear. Therefore, if there exists an association between depression and new-onset diabetes, further research into the association among high BMI, depression, and new-onset diabetes is crucial for the prevention of new-onset diabetes.

This study employed longitudinal cohort data from the United States. Data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) was used to investigate the impact of depression on new-onset diabetes and ascertain whether the association between depression and new-onset diabetes was mediated by high BMI.

Our study data were obtained from the HRS. The HRS is a longitudinal study that includes adults aged ≥ 50 years and their spouses in the United States, with a multi-stage area probability sample design. To maintain a sample size of approximately 20000 participants, new participants were recruited at 6-year intervals. This sample was sufficiently representative of the American population. Baseline data were collected in 1992 and every following 2 years through face-to-face or telephone interviews. Starting in 2006, approximately half of the HRS participants were invited to participate in an “enhanced face-to-face interview”, whereas the remaining half were invited 2 years later, alternating between the two cohorts. Physical characteristics, such as height and weight, were measured during the interviews, and participants provided blood samples for the biomarker analysis. Face-to-face interviews were conducted every 4 years. The Research and Development (RAND) Corporation cleaned and appended repeated measures to participants after each round (i.e., every 2 years), compiling a single longitudinal file that included many of the core HRS questions. The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board approved the HRS protocol, and all the participants provided informed consent. The HRS has been described in other topics[14].

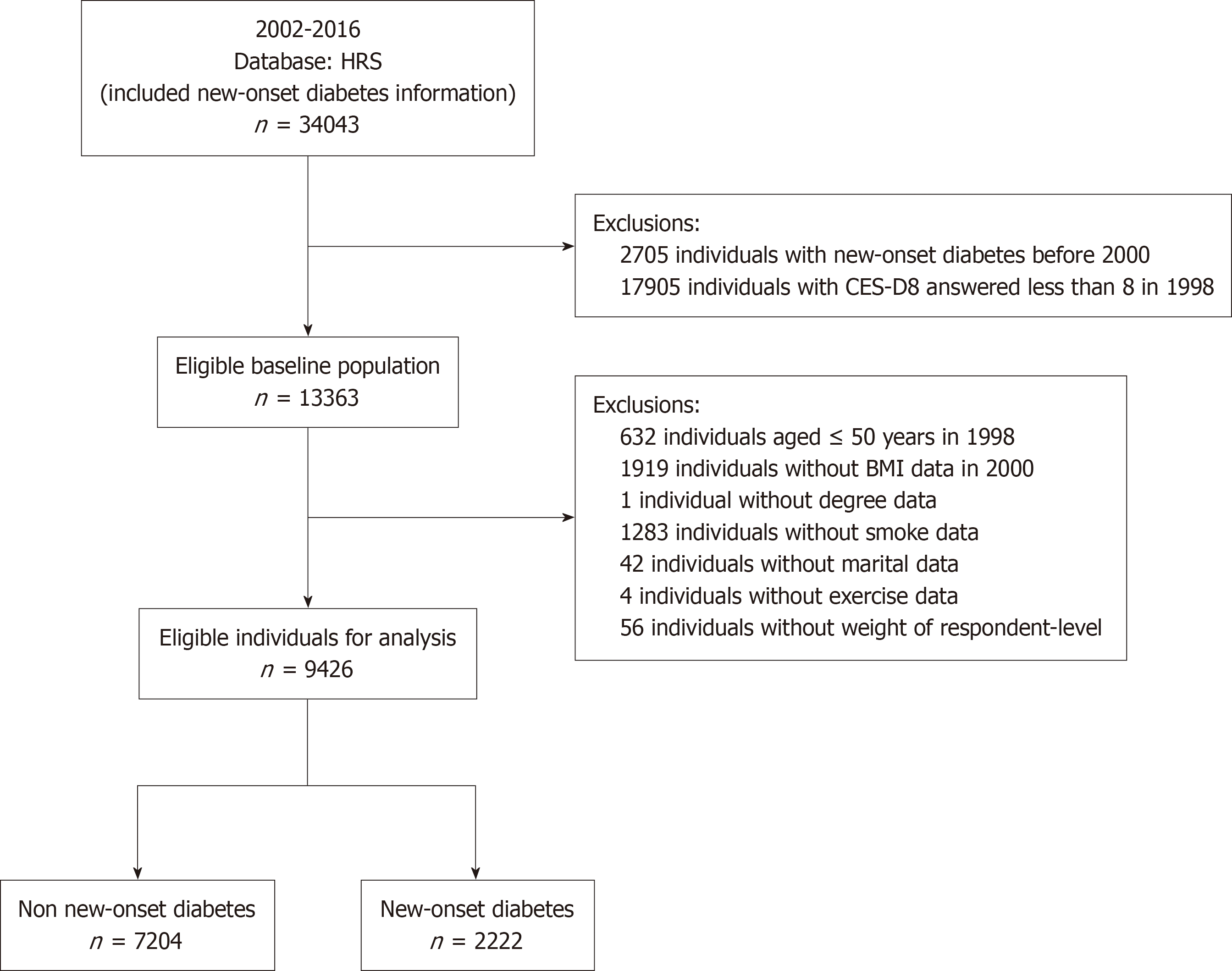

Our study used data from the 1998-2016 RAND HRS fat file survey, the HRS 2020 final release tracker file, and the 2006-2016 biomarker data. The biomarker data were from a national longitudinal study that examined the economic, health, marital, family status, and support systems of middle-aged and older Americans. Our study included individuals with a documented history of new-onset diabetes who responded to surveys from 2002 to 2016. Subsequently, 2705 individuals were excluded from the study owing to their diagnosis of new-onset diabetes in 1998 and 2000. A total of 17905 individuals were excluded from the study because of incomplete responses to the 8-item Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D8). Moreover, 632 individuals were excluded at baseline because they were < 50 years old. Additionally, 1919 individuals were excluded from the study because of the absence of BMI data. A total of 1330 individuals were excluded from the analysis because of missing covariate data. Moreover, 56 individuals were excluded from the study owing to a lack of weighting data provided by the complex sample from the HRS 2020 final release tracker file. Ultimately, 34043 participants were enrolled in our study, and 9426 respondents met the study’s inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, 1909 patients with new-onset diabetes and 7517 patients with non-new-onset diabetes were used to explore the research questions of our study. A flowchart of the study participants is provided in Figure 1.

Depression: The CES-D8 was used by the HRS to assess depression based on responses to statements such as “I felt lonely,” “I felt sad”, and “I could not get going”. This scale was developed by Radloff[15] in 1977 and is currently one of the most widely used scales for assessing depressive symptoms[16]. The validity of CES-D8 has been demonstrated in both middle-aged and older populations. The scale is rated on a scale of 0-8, and a cut-off score of ≥ 3 has been used as an indicator of clinical depression, with higher scores indicating greater symptoms[17] (Supplementary Table 1). All questions in the CES-D8 were derived from the 1998 RAND HRS fat file survey. Therefore, depression was first assessed in 1998. Respondents who reported the use of tranquilizers or antidepressants were classified as depressed.

BMI: BMI was calculated using objective measurements of height and weight collected by HRS interviewers during the 2000 RAND HRS fat file survey. The weights of respondents were provided in pounds and heights in feet/inches by the HRS; our study converted these units to kilograms and meters, and BMI was calculated by dividing weight by the square of height. Overweight was defined by BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 in our study[18]. In cases where height was missing in the questionnaire but weight was available, we used the height variable from the neighboring wave to fill in the missing data, assuming that the height of middle-aged and older adults remained constant in the short term. BMI was measured in 2000.

New-onset diabetes: In the 1998-2016 RAND HRS fat file survey, participants were asked questions such as, ”Has a doctor ever told you that you have diabetes or high blood sugar?” “Are you currently taking medication to treat or control your diabetes?” and “Are you currently using insulin shots or pumps?”. Participants were considered to have new-onset diabetes if they answered “yes” to any of the three questions. However, approximately 11% of adults with diabetes are unaware of their condition and are therefore unable to accurately report their diabetes status[19]. For the diagnosis of new-onset diabetes, hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c) is recommended as an indicator of glycemic control over the past to 2-3 months[20]. According to the American Diabetes Association criteria, an individual with an HbA1c level of ≥ 6.50% can be classified as having diabetes[20]. Therefore, using HbA1c to measure the diabetic status may reduce the underdiagnosis of new-onset diabetes. However, the HRS only provided HbA1c data for the population after 2006. Participants were also considered diabetic if their HbA1c was ≥ 6.5% in the 2006-2016 Biomarker data. Our study followed HRS recommendations and used HbA1c values adjusted according to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)[19].

In summary, the diagnoses of new-onset diabetes in 2002 and 2004 were based on the three questions from the RAND HRS fat file survey. Furthermore, from 2006 to 2016, in addition to the three questions above, respondents were also diagnosed as having new-onset diabetes if they had an HbA1c level of ≥ 6.50%.

Covariates: We controlled for potential confounding variables, and the covariates were all obtained from the 1998 RAND HRS fat file survey for the present analysis, including age (≥ 75/< 75), sex (male/female), ethnicity (Hispanic/others), education level (bachelor’s degree and above/less than a bachelor’s degree), smoking status (yes/no), drinking status (yes/no), marital status (married/unmarried), exercise status (have exercise habit/no exercise habit), appetite loss (yes/no), and appetite increase (yes/no). Smoking status was defined as smoking ≥ 100 cigarettes in a lifetime (not including pipes or cigars), and drinking status was defined as drinking any alcoholic beverage such as beer, wine, or liquor. The term “have exercise habit” was used to describe individuals who engaged in vigorous exercise on ≥ 3 occasions per week. “Appetite loss” and “appetite increase” were defined by asking respondents whether they had experienced these conditions in the past 2 weeks. If the respondents did not provide an answer, their condition was classified as “no”.

Categorical variables were presented as a number (percentage), and the differences between the new-onset and non-new-onset diabetes groups were compared using the Pearson χ2 test. Weighted logistic regression was used to obtain the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs) of depression and being overweight for the risk of new-onset diabetes in both unadjusted and adjusted models. The adjusted models considered the confounding effects of traditional risk factors for new-onset diabetes, including age, sex, ethnicity, education level, smoking status, drinking status, marital status, exercise status, appetite loss, and appetite increase. To shed light on the potential mechanisms of depression on the risk of new-onset diabetes, we further conducted a mediation analysis to examine whether being overweight could account for the association between depression and new-onset diabetes and the increased risk of new-onset diabetes. After adjusting confounding effects of traditional risk of diabetes. First, we estimated the ORs of depression for overweight, and the ORs of overweight for new-onset diabetes. Then, we calculated the ORs of depression for new-onset diabetes after adjusting for the overweight status. Finally, the Sobel test was used to assess the mediating effect of overweight. Furthermore, patients diagnosed with new-onset diabetes during 2000-2002 were excluded, and a sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the mediating effect of overweight. Sample weighting and a complex study design were considered in all the analyses. Professional statisticians reviewed the statistical methods used in this study. All calculations were performed and tables were created using R (version 4.3.3), and graphs were generated using Microsoft Visio Drawing. A two-sided test P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Our study included 9426 middle-aged and older individuals in the United States, 23% of whom developed new-onset diabetes between 2002 and 2016. Compared with the non-new-onset diabetes group, the new-onset diabetes group had more people with depression (22.5% vs 19.0%) and having an overweight status (83.3% vs 60.6%). Patients with new-onset diabetes were more likely to be Hispanic, have a low education level, be men, be < 75 years old, be non-drinkers, and had no exercise habits (P < 0.05). In contrast, the smoking and marital status did not differ between the groups (Table 1).

| Characteristic | All respondents, unweighted No. (weighted %) | Weighted (%) | P value | |

| Non-new-onset diabetes | New-onset diabetes | |||

| Depression | 1909 (20.3) | 19.0 | 22.5 | 0.002 |

| Overweight | 6226 (66.1) | 60.6 | 83.3 | < 0.001 |

| Ethnicity | < 0.001 | |||

| Hispanic | 555 (5.9) | 3.9 | 7.1 | |

| Others | 8871 (94.1) | 96.1 | 92.9 | |

| Degree | < 0.001 | |||

| Bachelor's degree and above | 2217 (23.5) | 26.9 | 20.9 | |

| Others | 7209 (76.5) | 73.1 | 79.1 | |

| Male | 3837 (40.7) | 42.4 | 46.5 | 0.003 |

| Age (year) | < 0.001 | |||

| ≥ 75 | 1466 (15.6) | 16.7 | 8.5 | |

| < 75 | 7960 (84.4) | 83.3 | 91.5 | |

| Smoke | 1744 (18.5) | 20.9 | 23.0 | 0.091 |

| Drink | 5204 (55.2) | 60.1 | 53.5 | < 0.001 |

| Marital | 6501 (68.7) | 66.5 | 67.1 | 0.674 |

| Exercise | 4670 (49.5) | 51.5 | 46.4 | < 0.001 |

Depression was associated with an increased risk of new-onset diabetes (OR: 1.18, 95%CI: 1.03-1.35, P value: 0.014) after adjustment for traditional risk factors, including age, sex, ethnicity, education level, smoking status, drinking status, marital status, exercise status, appetite loss, and appetite increase. Similarly, overweight was also associated with an increased risk of new-onset diabetes after adjustment for traditional risk factors (OR: 3.11, 95%CI: 2.70-3.58, P value < 0.001; Table 2).

| Characteristic | Unadjusted model | Adjusted model | ||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Depression | 1.29 (1.16-1.44) | < 0.001 | 1.18 (1.03-1.35) | 0.014 |

| Overweight | 3.24 (2.87-3.66) | < 0.001 | 3.11 (2.70-3.58) | < 0.001 |

In the adjusted model, depression significantly increased the risk of overweight (OR: 1.20, 95%CI: 1.06-1.36, P value: 0.004). Adjustment for overweight attenuated the OR of depression from 1.18 (1.03-1.35) to 1.14 (1.00-1.30; P value from 0.014 to 0.053). Furthermore, depression was significantly associated with the risk of new-onset diabetes (total effect: 0.33), and overweight had a partially mediating effect on depression for the risk of new-onset diabetes (indirect effect: 0.20, P of Sobel test = 0.003). This study also showed that overweight statistically explained almost 61% of the association between depression and new-onset diabetes (Table 3).

| β (SD) | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Model A (overweight as the outcome) | |||

| Depression | 0.18 (0.06) | 1.20 (1.06-1.36) | 0.004 |

| Model B (new-onset diabetes as the outcome) | |||

| Overweight | 1.13 (0.07) | 3.10 (2.69-3.57) | < 0.001 |

| Model C (new-onset diabetes as the outcome) | |||

| Depression | 0.13 (0.07) | 1.14 (1.00-1.30) | 0.053 |

| Sobel test for mediation effect | 0.003 |

The analysis after excluding participants with new-onset diabetes diagnosed between 2000 and 2002 (n = 851) at follow-up led to a similar conclusion. Depression was significantly associated with the risk of new-onset diabetes (total effect: 0.31) after adjusting for traditional risk factors. Being overweight had a partial mediating effect on depression for the risk of new-onset diabetes (indirect effect: 0.23, P of Sobel test: 0.037) and statistically explained approximately 75% of the association between depression and new-onset diabetes (Supplementary Table 2).

This study revealed two key findings: (1) Depression was positively associated with the risk of new-onset diabetes in middle-aged and older populations in the United States; and (2) Overweight partially mediated the depression-to-diabetes pathway, accounting for 61% of the risk of new-onset diabetes.

The role of depression has been a popular topic in recent studies on new-onset diabetes. Several studies have at

The precise mechanism by which depression affects new-onset diabetes remains unclear. Our findings showed that being overweight might act as a partial mediator of depression in new-onset diabetes in middle-aged and older populations. This indicates that being overweight may be the underlying cause of new-onset diabetes rather than depression. Notably, being overweight is merely a state that a person exhibits and is influenced by both innate genetics and a multitude of lifestyle factors[24]. Change in appetite is an important lifestyle factor that influences the overweight status. Notably, both atypical depression, characterized by increased appetite[25], and typical depression, marked by decreased appetite[26], have the capacity to increase BMI and contribute to being overweight. An 18-year study of middle-aged adults in the United States indicated that emotional eating played a significant role in the development of depression and increased BMI[12]. A review published by the Lancet in 2018 mentioned that people with anorexia-type depression usually reduce their physical activity or avoid social interactions, which may lead to an increase in BMI[8]. In addition, other lifestyle factors associated with depression, such as sedentary behavior, sleep habits, mental stress, and drug use, can also influence BMI levels and, consequently, new-onset diabetes. Thus, new-onset diabetes may not necessarily be a direct complication of depression. In fact, depressive states may lead to behaviors that increase the risk of being overweight, which, in turn, increases the risk of new-onset diabetes.

These findings have significant public health implications. New-onset diabetes not only reduces the quality of life of middle-aged and older adults but also leads to serious diseases such as diabetic nephropathy[27], diabetic foot disease[28], diabetic retinopathy[29], and diabetic cerebrovascular disease[30]. Therefore, it is important to understand and identify the risk factors for new-onset diabetes to facilitate early diagnosis and reduce diabetes-related harm. Depression was positively associated with the risk of new-onset diabetes in middle-aged and older populations in the United States, and 61% of this process was partially mediated by overweight. In other words, new-onset diabetes was not a direct complication of depression; rather, depressive states led to behaviors that increased the risk of being overweight, which in turn increased the risk of new-onset diabetes. Therefore, identifying lifestyle factors that may lead to an increased risk of being overweight in depressed patients and controlling them are of great clinical significance for preventing new-onset diabetes. In addition to the direct treatment of depression, behavioral interventions for high-risk lifestyle factors should be integrated with weight management to develop a comprehensive intervention program to improve the overall health of middle-aged and older populations.

This study exhibited strengths and limitations. A significant strength of this study is that the data were obtained from a longitudinal follow-up cohort provided by the HRS for up to 20 years. However, this study had several limitations. First, we could not exclude the influence of bipolar disorder (BD) on the association between depression and new-onset diabetes, even though the age at onset of BD (15-25 years) was much lower than the age of the middle-aged and older populations. Second, lifestyle factors, including dietary habits, sedentary behavior, sleeping habits, and drug use, may impact the development of depression and new-onset diabetes, despite BMI reflecting lifestyle to a certain extent. However, information on lifestyle factors other than exercise and dietary patterns was not collected in the HRS.

Depression was positively associated with the risk of new-onset diabetes in middle-aged and older populations in the United States, and 61% of this process was partially mediated by overweight. This indicated that new-onset diabetes was not a direct complication of depression, but rather that depressive states led to behaviors that increased the risk of being overweight and, consequently, new-onset diabetes. Our findings have potential value in the prediction of new-onset diabetes in middle-aged and older populations that may benefit from specific interventions if validation studies can confirm our findings in other cohorts of different populations. Furthermore, randomized controlled trials are warranted to investigate whether controlling lifestyle factors that may lead to an increased risk of being overweight reduces the risk of new-onset diabetes in patients with depression.

The authors thank all the health professionals of HRS.

| 1. | Li HQ, Chi S, Dong Q, Yu JT. Pharmacotherapeutic strategies for managing comorbid depression and diabetes. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2019;20:1589-1599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | GBD 2021 Diabetes Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2023;402:203-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2437] [Cited by in RCA: 2570] [Article Influence: 856.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (18)] |

| 3. | Umpierrez G, Korytkowski M. Diabetic emergencies - ketoacidosis, hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state and hypoglycaemia. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12:222-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 317] [Article Influence: 31.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | de Boer IH, Zelnick L, Afkarian M, Ayers E, Curtin L, Himmelfarb J, Ikizler TA, Kahn SE, Kestenbaum B, Utzschneider K. Impaired Glucose and Insulin Homeostasis in Moderate-Severe CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:2861-2871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Einarson TR, Acs A, Ludwig C, Panton UH. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes: a systematic literature review of scientific evidence from across the world in 2007-2017. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17:83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1295] [Cited by in RCA: 1465] [Article Influence: 183.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | van Sloten TT, Sedaghat S, Carnethon MR, Launer LJ, Stehouwer CDA. Cerebral microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes: stroke, cognitive dysfunction, and depression. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:325-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 469] [Article Influence: 78.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Haroon NN, Austin PC, Shah BR, Wu J, Gill SS, Booth GL. Risk of dementia in seniors with newly diagnosed diabetes: a population-based study. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1868-1875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Malhi GS, Mann JJ. Depression. Lancet. 2018;392:2299-2312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1255] [Cited by in RCA: 2835] [Article Influence: 354.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tang B, Yuan S, Xiong Y, He Q, Larsson SC. Major depressive disorder and cardiometabolic diseases: a bidirectional Mendelian randomisation study. Diabetologia. 2020;63:1305-1311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhang M, Chen J, Yin Z, Wang L, Peng L. The association between depression and metabolic syndrome and its components: a bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hemmy Asamsama O, Lee JW, Morton KR, Tonstad S. Bidirectional longitudinal study of type 2 diabetes and depression symptoms in black and white church going adults. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2015;14:25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Vittengl JR. Mediation of the bidirectional relations between obesity and depression among women. Psychiatry Res. 2018;264:254-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lake S, Krook A, Zierath JR. Analysis of insulin signaling pathways through comparative genomics. Mapping mechanisms for insulin resistance in type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2003;111:191-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hauser RM, Willis RJ. Survey Design and Methodology in the Health and Retirement Study and the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. Popul Dev Rev. 2004;30:209-235. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Populat. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385-401. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Zimmerman FJ, Katon W. Socioeconomic status, depression disparities, and financial strain: what lies behind the income-depression relationship? Health Econ. 2005;14:1197-1215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ornstein KA, Aldridge MD, Garrido MM, Gorges R, Meier DE, Kelley AS. Association Between Hospice Use and Depressive Symptoms in Surviving Spouses. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1138-1146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Beeri MS, Tirosh A, Lin HM, Golan S, Boccara E, Sano M, Zhu CW. Stability in BMI over time is associated with a better cognitive trajectory in older adults. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18:2131-2139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Crimmins E, Kim JK, McCreath H, Faul J, Weir D, Seeman T. Validation of blood-based assays using dried blood spots for use in large population studies. Biodemography Soc Biol. 2014;60:38-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2014;37 Suppl 1:S81-S90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2986] [Cited by in RCA: 3566] [Article Influence: 297.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (18)] |

| 21. | Cai J, Zhang S, Wu R, Huang J. Association between depression and diabetes mellitus and the impact of their comorbidity on mortality: Evidence from a nationally representative study. J Affect Disord. 2024;354:11-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Vimalananda VG, Palmer JR, Gerlovin H, Wise LA, Rosenzweig JL, Rosenberg L, Ruiz-Narváez EA. Depressive symptoms, antidepressant use, and the incidence of diabetes in the Black Women's Health Study. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2211-2217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wang Z, Du Z, Lu R, Zhou Q, Jiang Y, Zhu H. Causal relationship between diabetes and depression: A bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. J Affect Disord. 2024;351:956-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zhang M, Ward J, Strawbridge RJ, Celis-Morales C, Pell JP, Lyall DM, Ho FK. How do lifestyle factors modify the association between genetic predisposition and obesity-related phenotypes? A 4-way decomposition analysis using UK Biobank. BMC Med. 2024;22:230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Thase ME. Recognition and diagnosis of atypical depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68 Suppl 8:11-16. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Sachdeva B, Sachdeva P, Ghosh S, Ahmad F, Sinha JK. Ketamine as a therapeutic agent in major depressive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: Potential medicinal and deleterious effects. Ibrain. 2023;9:90-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Pelle MC, Provenzano M, Busutti M, Porcu CV, Zaffina I, Stanga L, Arturi F. Up-Date on Diabetic Nephropathy. Life (Basel). 2022;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Tentolouris N, Edmonds ME, Jude EB, Vas PRJ, Manu CA, Tentolouris A, Eleftheriadou I. Editorial: Understanding Diabetic Foot Disease: Current Status and Emerging Treatment Approaches. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:753181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Li H, Liu X, Zhong H, Fang J, Li X, Shi R, Yu Q. Research progress on the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. BMC Ophthalmol. 2023;23:372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Shukla V, Shakya AK, Perez-Pinzon MA, Dave KR. Cerebral ischemic damage in diabetes: an inflammatory perspective. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14:21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |