Published online Feb 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i2.95463

Revised: September 10, 2024

Accepted: October 22, 2024

Published online: February 15, 2025

Processing time: 263 Days and 15.9 Hours

Food insecurity (FI) during pregnancy negatively impacts maternal health and raises the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH), resulting in adverse outcomes for both mother and baby.

To investigate the relationships between FI and pregnancy outcomes, particularly GDM and PIH, while also examining the mediating role of the dietary diversity score (DDS).

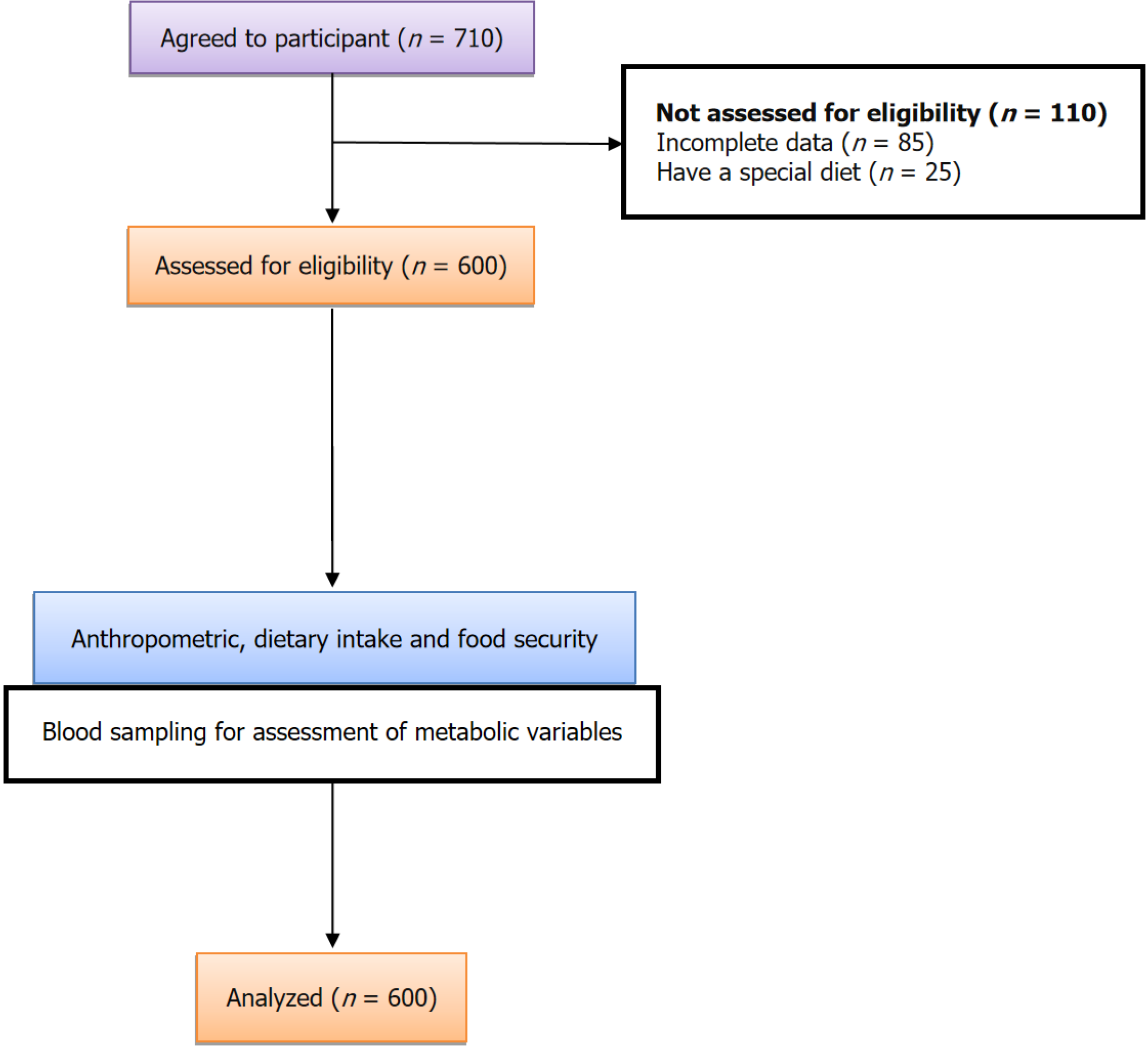

A cross-sectional study was undertaken to examine this relationship, involving 600 pregnant women. Participants were women aged 18 years or older who provided complete data on FI and pregnancy outcomes. The FI was measured via the Household Food Security Survey Module, with GDM defined as fasting plasma glucose levels of ≥ 5.1 mmol/L or a 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test value of ≥ 8.5 mmol/L. The DDS is determined by evaluating one's food con

Seventeen percent of participants reported experiencing FI during pregnancy. The study found a significant association between FI and an elevated risk of GDM [odds ratio (OR) = 3.32, 95%CI: 1.2-5.4]. Once more, food-insecure pregnant wo

These findings underscore the serious challenges that FI presents during pregnancy and its effects on maternal and infant health. Additionally, the study explored how DDS mediates the relationship between FI and the incidence of GDM.

Core Tip: Ensuring proper nutrition and food security during pregnancy is vital for maintaining maternal health and reducing the risk of complications like gestational diabetes mellitus and pregnancy-induced hypertension. Promoting dietary diversity and addressing food insecurity can lead to healthier outcomes for both mother and baby. Healthcare providers and policymakers should prioritize addressing these issues to improve overall maternal and infant health.

- Citation: Hou HL, Sun GX. Associations between food insecurity with gestational diabetes mellitus and maternal outcomes mediated by dietary diversity: A cross-sectional study. World J Diabetes 2025; 16(2): 95463

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v16/i2/95463.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i2.95463

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) are significant complications of pregnancy that have been linked to negative neonatal and maternal outcomes[1]. These conditions can lead to complications such as preterm delivery, macrosomia, and an increased risk of chronic diseases in both mother and child[2]. The etiology of GDM and PIH is multifaceted, involving complex interactions between genetic predisposition, metabolic factors, and environmental influences[3,4]. Among the environmental factors, food insecurity (FI) has emerged as a potential determinant of adverse pregnancy outcomes[5,6]. The FI refers to the limited or uncertain access to safe, sufficient, and nutritious food that is essential for maintaining a healthy lifestyle[7]. This issue affects a substantial number of households worldwide, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. The FI is associated with sub

Pregnancy represents a critical period when the nutritional needs of both the mother and the developing fetus are substantially increased. Adequate maternal nutrition is crucial for supporting optimal fetal growth and development, as well as maintaining the mother's health[9]. However, FI during pregnancy can disrupt the attainment of optimal nutrition, potentially leading to adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes[10,11]. During pregnancy, essential nutrients like folate, iron, calcium, and omega-3 fatty acids are crucial for maternal and fetal health. However, food-insecure women often rely on low-quality, high-calorie foods, leading to lower dietary diversity and inadequate intake of fruits, vegetables, meats, and dairy[12]. This deficiency can result in decreased potassium and calcium, raising the risk of hypertension and diabetes by Jouanne et al[9]. Additionally, the stress associated with FI further exacerbates these health issues, as higher stress levels are linked to poor mental health and increased risk of diabetes

Dietary diversity, defined as the consumption of a variety of different food groups, has been proposed as a potential mediator in the relationship between FI and pregnancy outcomes[12,13]. A diverse diet ensures the intake of a wide range of essential nutrients, which is crucial for maternal and fetal well-being[14]. Previous studies have suggested that higher DDS is associated with a reduced risk of GDM and gestational hypertension, as well as improved maternal and neonatal outcomes[15].

However, the associations between FI, GDM, gestational hypertension, DDS, and maternal-neonatal outcomes have not been extensively investigated, and the existing evidence remains limited and inconsistent. Therefore, this cross-sectional study aims to examine the associations of FI with GDM and gestational hypertension, and to clarify the possible me

This cross-sectional study included 600 women who visited Shanxi Maternal and Child Health Hospital within the first 10 days after giving birth. Participants were included if they were willing to participate in the study and did not have chronic medical conditions such as overt diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, renal diseases, epilepsy, or anemia. Twenty-one participants were excluded due to incomplete questionnaires. In an effort to obtain a representative sample, we employed a stratified sampling design, dividing the Shanxi province into three geographic regions based on socio

Ethical clearance was obtained from the relevant institutional review board prior to the commencement of the study. All participants provided informed consent, ensuring that ethical standards were upheld throughout the research process. The study adhered to the STROBE guidelines for reporting observational studies. The research received approval from Children’s Hospital of Shanxi Committee (Approval Number: KLT6230511).

Maternal height and weight were measured using standard procedures and instruments (SECA) at study enrollment and subsequent visits. Participants were asked to recall their pre-pregnancy weight. Weight gain was determined by subtracting the pre-pregnancy weight from the weight in the third trimester. Pre-pregnancy weight was retrieved either from medical records or, if unavailable, obtained through self-report during the participant's first visit.

Data on FI were collected between 22 and 28 weeks of gestation using the Chinese Food Security Module of the Household Food Security Questionnaire (Supplementary material), which demonstrated acceptable reliability with an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.73. The primary focus of this study was household food security, assessed using the 18-item United States Household Food Security Survey Module. A composite score was generated from affirmative responses, with higher scores indicating greater FI. Food security was defined as zero affirmative responses, marginal food security as 1-2 responses, and FI as three or more responses, encompassing low and very low food security categories as per United States Department of Agriculture definitions[16]. The reliability of the questionnaire was assessed using the test-retest method, yielding an appropriate ICC value of 0.73. FI status was divided into three groups: Food secure (FS), FI, and marginally FS (MFS).

During fasting (after abstaining from food for 10 hours overnight), blood samples were collected. Glucose levels were determined using the glucose oxidase method. Commercial diagnostic tools were used to measure total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and triglycerides. Friedewald's formula was employed to calculate low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol values based on these measurements as well as total cholesterol and triglyceride levels.

All pregnant women were subjected to a routine 2-hour 75 g oral glucose tolerance test between the 24th and 28th week of gestation. The diagnosis of GDM was based on fasting plasma glucose levels of ≥ 5.6 mmol/L or 2-hour plasma glucose levels of ≥ 7.8 mmol/L, as per the guideline[17].

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP respectively) were also measured after a period of rest. PIH is well-defined as a DBP of 90 mmHg or higher and/or a SBP of 140 mmHg or higher that occurs after 20 weeks of gestation in women who had normal blood pressure prior to pregnancy[18].

Dietary intake was evaluated using a validated quantitative food frequency questionnaire. All consumed food items were categorized into nine food groups: Starch milk (including all dairy products), green leafy vegetables, vitamin A (carrots, apricots, sweet potatoes, cantaloupe), roots and starchy vegetables (such as potatoes and cereals), vitamin-rich fruits and vegetables, other fruits, fish (fish and seafood), meat, legumes (seeds and nuts), and oils and fats. The dietary diversity score (DDS) ranged from 0 to 9, with one point assigned for each food group consumed. The total DDS was the sum of scores from the nine main food groups[14]. To clarify, DDS refers to the variety of foods consumed, which is crucial for adequate nutrition. Dietary insecurity encompasses not only the lack of access to safe and nutritious food but also concerns regarding unsafe food practices, including the use of food additives. Furthermore, a pregnant woman's un

Statistical analysis was done via Stata version 13, thru significance fixed at a P value less than 0.05. The normality of quantitative variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, confirming a normal distribution for all variables. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics, maternal outcomes, and neonatal outcomes both overall and by food security status. The allocation of FI status was likewise displayed for every subgroup. A logistic regression model was utilized to explore the relationship between FI and PIH, GDM, adjusting for pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) and age. ANOVA and independent samples tests were employed to compare means. One-way analysis was used to compare general characteristics across DDS quartile categories. The Tukey post hoc test was applied to identify statistically significant pairwise differences. To investigate the potential mediating role of DDS between FI and GDM, a parallel mediator approach was employed, utilizing distinct indicators as mediators.

Out of the 600 women involved in this study, the median age was 32.95 years. Among the participants, approximately half (50%) had obtained at least a high school education, and 37% had an annual household income below $15000. Within our sample, 226 women (37%) were classified as marginally MFS, and 114 women (17%) were considered FI. Additionally, 76 women (13%) were diagnosed with GDM during their current pregnancy. Compared to food-secure women, women who were MFS/FI were more likely to have GDM (P = 0.001), have a lower annual household income, and have a higher rate of PIH (Table 1). There was a statistically significant higher occurrence of neonatal complication, including neonatal intensive care units (NICU) admission, in the FI group compared to the FS group (53% vs 16% respectively, P < 0.001). Additionally, there was a significantly higher rate of extremely low birth weight infants in the FI group compared to the FS group (16% vs 3% respectively, P < 0.001). FI was associated with a higher prevalence of metabolic disturbances, such as elevated foetal bovine serum (FBS), LDL, and triglyceride levels compared to the FS group. This suggests that FI has a detrimental impact on these metabolic outcomes. The mean DDS values for FS and FI during pregnancy were 7.05 and 5.78, respectively (P < 0.001), suggesting that FI has a negative impact on DDS score and an additional adverse effect on pregnancy outcomes (Table 2).

| Variable | Food secure | Marginally secure | Food insecure | All participants | P value |

| Age (years) | 32.16 ± 7.76 | 33.5 ± 7.17 | 33.76 ± 8.01 | 32.95 ± 7.3 | 0.056 |

| Education | |||||

| Less than 12th grade | 116 (43) | 120 (53) | 58 (56) | 294 (49) | 0.008a |

| High school degree | 80 (30) | 60 (26.5) | 34 (32) | 174 (29) | |

| More than high school | 74 (27) | 46 (21.5) | 12 (12) | 132 (22) | |

| Income | |||||

| Good | 197 (73) | 22 (10) | 6 (6) | 225 (37.5) | 0.001a |

| Average | 50 (19) | 76 (33) | 20 (19) | 146 (24.5) | |

| Poor | 22 (8) | 128 (57) | 78 (75) | 228 (38) | |

| Physical activity (total MET) | 62.10 ± 2.67 | 62.09 ± 3.2 | 61.36 ± 2.8 | 61.97 ± 2.9 | 0.066 |

| DDS | 7.05 ± 1.5 | 6.34 ± 1.2 | 5.78 ± 1.9 | 6.56 ± 1.3 | 0.001a |

| TG (mg/dL) | 159.38 ± 40.67 | 175.8 ± 76.1 | 174.05 ± 50.74 | 168.1 ± 58.5 | 0.004a |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 122.23 ± 27.34 | 124.14 ± 25.7 | 125.88 ± 23.2 | 123.58 ± 26.04 | 0.442 |

| TC (mg/dL) | 170.82 ± 27.7 | 180.04 ± 29.5 | 175.88 ± 23.3 | 175.17 ± 27.98 | 0.001a |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 44.45 ± 7.7 | 45.47 ± 8.2 | 42.75 ± 7.58 | 44.54 ± 7.95 | 0.015a |

| FBS (mg/dL) | 86.89 ± 11.9 | 85.74 ± 12.28 | 89.13 ± 15.09 | 86.85 ± 12.71 | 0.08 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 115.33 ± 14.43 | 116.29 ± 16.20 | 117.96 ± 15.66 | 116.15 ± 15.3 | 0.326 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 73.88 ± 9.4 | 72.8 ± 9.4 | 74.3 ± 8.7 | 73.56 ± 9.31 | 0.291 |

| Nutrient | |||||

| Total energy (kcal/day) | 2153.11 ± 319.9 | 2072.5 ± 311.2 | 2010.4 ± 376.1 | 2098.1 ± 331.1 | 0.001a |

| Carbohydrate (gr/day) | 272.18 ± 61.6 | 272.05 ± 68.4 | 279.95 ± 64.8 | 273.48 ± 64.8 | 0.535 |

| Protein (gr/day) | 89.14 ± 16.4 | 88.65 ± 16.6 | 81.11 ± 16.6 | 87.56 ± 16.7 | 0.001a |

| Fat (gr/day) | 73.08 ± 15.5 | 68.70 ± 16.2 | 69.04 ± 16.3 | 70.73 ± 16.07 | 0.005a |

| Fiber (gr/day) | 19.9 ± 2.82 | 18.3 ± 6.34 | 16.22 ± 8.06 | 18.3 ± 1.3 | 0.193 |

| Variable | Food secure | Marginally secure | Food insecure | All participants | P value |

| Maternal outcomes | |||||

| GDM | |||||

| No | 262 (84) | 202 (84) | 60 (65.5) | 524 (87) | 0.001a |

| Yes | 8 (16) | 24 (16) | 44 (34.5) | 76 (13) | |

| Hypertension/preeclampsia | |||||

| No | 248 (92) | 195 (85.5) | 65 (62.5) | 508 (84) | 0.001a |

| Yes | 22 (8) | 31 (4.5) | 39 (6.5) | 92 (16) | |

| Gestational age | 37.44 ± 2.1 | 37.47 ± 2.1 | 37.21 ± 2.2 | 37.44 ± 2.1 | 0.539 |

| Weight before pregnancy | 70.26 ± 9.3 | 71.24 ± 9.7 | 71.08 ± 10.1 | 70.77 ± 9.6 | 0.494 |

| BMI before pregnancy | 26.18 ± 3.1 | 26.61 ± 2.9 | 26.65 ± 4.1 | 26.24 ± 3.2 | 0.266 |

| Weight gain (kg) | 9.46 ± 2.5 | 9.03 ± 4.08 | 10.27 ± 2.85 | 9.44 ± 6.20 | 0.236 |

| Neonatal outcomes | |||||

| Neonatal RDS | |||||

| No | 268 (99.3) | 228 (100) | 92 (88.5) | 586 (98) | 0.001a |

| Yes | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 12 (11.5) | 14 (2) | |

| NICU admission | |||||

| No | 254 (94) | 195 (86) | 51 (49) | 500 (83) | 0.001a |

| Yes | 16 (6) | 31 (14) | 53 (51) | 100 (17) | |

| ELBW | |||||

| No | 267 (99) | 226 (100) | 88 (84) | 581 (96.5) | 0.001a |

| Yes | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 16 (16) | 19 (3.5) | |

| Birth weight (kg) | 3.61 ± 0.25 | 3.63 ± 0.18 | 3.41 ± 0.61 | 3.58 ± 0.33 | 0.001a |

The participants' characteristics related to maternal and neonatal outcomes were presented in Table 3. A higher DDS was associated with a healthier diet, as those in the upper categories consumed a greater variety of foods (8.30 vs 4.87 respectively, P < 0.001). Additionally, individuals with higher DDS had significantly higher levels of HDL and lower levels of triglycerides. Furthermore, individuals in the highest DDS quartile had lower FBS levels compared to those in the lowest quartile (84 vs 93 respectively, P = 0.001). However, there were no significant differences in other metabolic variables, including serum LDL-cholesterol, total cholesterol levels, and SBP and DBP, between DDS quartile categories. Regarding neonatal outcomes, there were no significant differences across DDS quartiles. Similar to FI category, women with lower DDS scores were more likely to have GDM (P = 0.001) and have a higher rate of PIH compared to those in the highest quartile of DDS (P = 0.004; Table 3).

| Variable | Q1 (n = 108) | Q2 (n = 164) | Q3 (n = 196) | Q4 (n = 132) | P value |

| DDS | 4.88 ± 0.36 | 5.87 ± 0.15 | 6.90 ± 0.2 | 8.30 ± 1.17 | 0.001a |

| TG (mg/dL) | 189.01 ± 88.23 | 170.78 ± 48.8 | 159.9 ± 47.4 | 159.9 ± 49.6 | 0.001a |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 124.68 ± 28.5 | 125.46 ± 26.3 | 123.43 ± 26.2 | 120.57 ± 23.6 | 0.422 |

| TC (mg/dL) | 179.59 ± 23.3 | 176.46 ± 28.6 | 174.80 ± 29.5 | 170.5 ± 27.8 | 0.08 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 41.68 ± 8.2 | 44.76 ± 9.16 | 45.23 ± 7.1 | 45.57 ± 6.8 | 0.001a |

| FBS (mg/dL) | 92.91 ± 10.7 | 86.35 ± 13.9 | 85.81 ± 12.6 | 84.03 ± 11.1 | 0.001a |

| SBP (mmHg) | 117.7 ± 15.7 | 118.43 ± 17.2 | 114.88 ± 13.1 | 113.91 ± 15.1 | 0.030a |

| DBP (mmHg) | 74.46 ± 8.3 | 74.01 ± 10.4 | 73.39 ± 8.5 | 72.52 ± 9.5 | 0.376a |

| Maternal outcomes | |||||

| GDM | |||||

| No | 76 (70.5) | 129 (78.5) | 162 (82.5) | 118 (89.5) | 0.001a |

| Yes | 44 (57) | 30 (40) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| Hypertension/preeclampsia | |||||

| No | 87 (80) | 130 (79.5) | 175 (89.5) | 116 (88) | 0.024a |

| Yes | 21 (20) | 34 (20.5) | 21 (10.5) | 16 (12) | |

| Gestational age | 37.67 ± 1.5 | 37.06 ± 2.2 | 37.33 ± 2.2 | 37.76 ± 1.9 | 0.016a |

| Weight before pregnancy | 72.11 ± 9.5 | 69.13 ± 10.09 | 71.33 ± 9.7 | 70.88 ± 8.7 | 0.056 |

| BMI before pregnancy | 26.18 ± 3.1 | 26.61 ± 2.9 | 26.65 ± 4.1 | 26.24 ± 3.2 | 0.266 |

| Total gestational weight gain (kg) | 11.12 ± 3.89 | 9.95 ± 2.50 | 7.89 ± 4.95 | 9.72 ± 1.83 | 0.001a |

| Neonatal outcomes | |||||

| Neonatal RDS | |||||

| No | 106 (98) | 158 (96.3) | 192 (96) | 130 (98.5) | 0.642 |

| Yes | 2 (2) | 6 (3.7) | 4 (2) | 2 (1.5) | |

| NICU admission | |||||

| No | 63 (59) | 123 (75) | 186 (95) | 128 (97) | 0.001a |

| Yes | 45 (41) | 41 (25) | 10 (5) | 4 (3) | |

| ELBW | |||||

| No | 106 (98) | 156 (95) | 191 (97.4) | 128 (97) | 0.526 |

| Yes | 2 (2) | 8 (5) | 5 (2.6) | 4 (3) | |

| Birth weight (kg) | 3.62 ± 0.26 | 3.53 ± 0.38 | 3.58 ± 0.32 | 3.61 ± 0.33 | 0.102 |

Table 4 displays the odds ratios (OR) and 95%CI for GDM and PIH across FI Status. In Model 1 (unadjusted), marginally secure food status is associated with an OR of 2.35 (95%CI: 1.55-3.5) for GDM, while FI shows a significantly higher OR of 4.52 (95%CI: 3.75-6.4), both statistically significant (P < 0.001). In Model 2 (adjusted for age, BMI, income, and weight gain, education), the OR for marginally secure food status decreases to 1.25 (95%CI: 0.85-1.70), yet FI increases to 3.64 (95%CI: 2.3-5.5), maintaining statistical significance (P < 0.001 for marginally secure and P = 0.002 for food insecure). For PIH, Model 1 indicates an OR of 2.77 (95%CI: 1.6-3.85) for marginally secure and 1.25 (95%CI: 1.1-1.65) for food insecure individuals (P < 0.001). In Model 2, the OR for marginally secure food status is 2.53 (95%CI: 1.84-3.55), while FI shows a decrease to 1.10 (95%CI: 1.02-1.44), with significance retained (P < 0.001 for marginally secure and P = 0.002 for food insecure). These findings underscore a significant association between FI and increased odds of adverse maternal health outcomes, highlighting the importance of addressing food security in prenatal care.

| Food security status | P value | |||

| Food secure | Marginally secure | Food insecure | ||

| Gestational diabetes Mellitus | ||||

| Model 1 | Reference | 2.35 (1.55-3.5) | 4.52 (3.75-6.4) | 0.001 |

| P value | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| Model 2 | Reference | 1.25 (0.85-1.70) | 3.64 (2.36-5.56) | 0.001 |

| P value | 0.001 | 0.002 | ||

| Gestational Hypertension | ||||

| Model 1 | Reference | 2.77 (1.6-3.85) | 1.25 (1.1-1.65) | 0.001 |

| P value | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| Model 2 | Reference | 2.53 (1.84-3.55) | 1.10 (1.02-1.44) | 0.001 |

| P value | 0.001 | 0.002 | ||

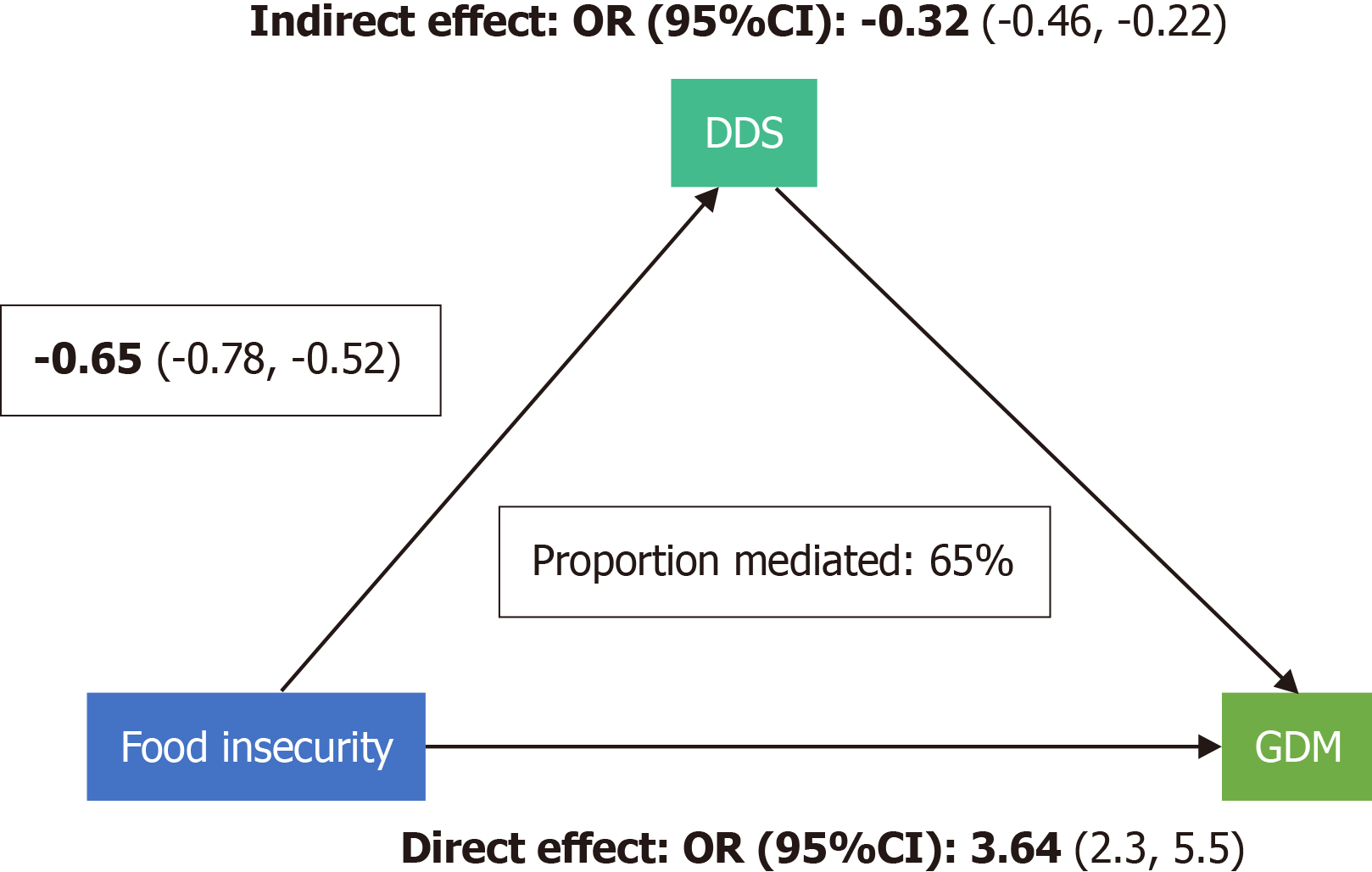

Our results suggest that the DDS plays a crucial mediating role in the relationship between FI and GDM incidence. Specifically, the mediation percentage of DDS was approximately 65%, indicating a significant influence in this association (Figure 2).

The present cross-sectional study aimed to investigate the associations between FI and GDM, PIH, and maternal outcomes, with a focus on the mediating role of the DDS. The study findings provide important insights into the relationship between FI and adverse pregnancy outcomes, highlighting the potential impact of dietary diversity on mitigating these risks. According to our results, the prevalence of FI was substantial, with 37% of women classified as MFS and 17% as FI. Women who were MFS/FI were more likely to have GDM, have a lower annual household income, and have a higher rate of PIH. Moreover, the FI group had a considerably higher occurrence of neonatal complications, such as NICU admission and extremely low birth weight infants, compared to the FS group. The FI was also associated with a higher prevalence of metabolic disturbances, including elevated FBS, LDL, and triglyceride levels. The study also examined the mediating role of DDS in the association between FI and GDM incidence. The findings showed that DDS played a significant mediating role, with approximately 65% mediation percentage, indicating a notable influence in this association.

Consistent with previous research, our study found a higher prevalence of FI among pregnant women, with 17% classified as food insecure. These findings align with national trends and highlight the persistent issue of FI among vulnerable populations, even during pregnancy[5]. This is concerning, as pregnancy is a critical period when adequate nutrition is essential for both maternal and fetal health[9]. FI during pregnancy can lead to inadequate intake of essential nutrients, including protein, vitamins, and minerals, which can have significant implications for maternal and fetal well-being[19]. This finding is consistent with studies in developed countries, where 2% to 25% of pregnant women report experiencing FI[5], but is lower than figures from studies conducted in countries like Ethiopia (40.0%)[20] and Iran (31%-40%)[21]. Discrepancies between studies could be due to variations in the tools used to assess FI (e.g., 10-item Radimer/Cornell hunger scale, 9-item household FI access scale, 18-item core food security module) and the characteristics of the study populations (e.g., education level, economic status, and food accessibility)[5,20,21].

FI has emerged as a significant public health concern, particularly among pregnant women. The study's results demonstrate that food-insecure women are more likely to develop GDM[11]. Several other studies have shown a consistent, significant relationship between FI among women, but only a few have shown evidence of a relationship between the FI and GDM and/or Glycemic control[5]. Although our study did not reveal a significant difference in maternal weight gain, we did find a significant glycemic control and occurrence of GDM among FI groups. This showed that patients with FI effect on GDM regardless of weight gain. This finding is consistent with previous research demonstrating an increased risk of GDM among food-insecure individuals[5,6]. The mechanisms underlying this as

The unhealthy diets identified in our study by low DDS may disrupt normal physiological and metabolic processes, contributing to the development of GDM. Further analysis of our data indicated a link between low DDS scores and inadequate glycemic control. Insufficient consumption of fruits and vegetables may deprive food insecure individuals of essential nutrients that protect against diseases like diabetes, which can result from poor nutrition[8]. Moreover, it is possible that women experiencing FI have limited nutrition knowledge, as well as less time and resources for preparing or engaging in healthy eating habits[28]. Additionally, pregnant women may face barriers that limit their access to food, exacerbating FI. While some studies emphasize food availability, utilization, and sustainability, others focus on eradicating poverty and malnutrition; however, tensions between sustainability and other dimensions of food security are often overlooked[29].

Furthermore, our study found that FI was associated with a higher rate of PIH. This aligns with previous research suggesting that FI is associated with hypertensive disorders during pregnancy[30]. The exact mechanisms linking FI to PIH are not fully understood but may involve the interplay of multiple factors. Inadequate nutrition due to FI can contribute to inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction, all of which are implicated in the development of hypertension[31]. Additionally, psychosocial stress associated with FI may contribute to the dysregulation of physiological processes involved in blood pressure control[32].

Importantly, our study highlighted the adverse neonatal outcomes associated with FI. The incidence of neonatal complications, including NICU admission, was significantly higher in the food-insecure group compared to the food-secure group. This finding is consistent with previous research linking FI to adverse birth outcomes[2,5,10]. Inadequate nutrition during pregnancy can negatively impact fetal growth and development, leading to increased risks of prema

The study also examined the role of DDS as a potential mediator of the associations between FI and maternal outcomes. A higher DDS was associated with a healthier diet and improved metabolic outcomes, including higher levels of HDL cholesterol and lower levels of triglycerides[12,14]. This suggests that promoting dietary diversity and ensuring access to a variety of nutritious foods during pregnancy may mitigate the adverse effects of FI on maternal health. The study also examined the role of DDS in mediating the association between FI and GDM incidence. The results showed that DDS significantly influenced this relationship, with approximately 65% of the association between FI and GDM being mediated by DDS. This underscores the importance of promoting a diverse and nutritious diet among food-insecure populations to mitigate the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

This study significantly contributes to the literature on food access during pregnancy and its effects on GDM and maternal-neonatal outcomes. Additionally, our sampling encompassed both rural and urban health centers, enhancing the generalizability of the findings. To our knowledge, our study is one of the few that examines FI in the context of GDM and evaluates the mediating role of DDS, which has shown importance in this mediation. We also recognized a limitation in our analysis: We lacked insights into how the convenience of individual food products might have affected the reliability or accuracy of our survey data. Existing literature indicates that while women often understand healthy eating principles, they face significant barriers to accessing nutritious foods due to socioeconomic constraints. This disconnect highlights the need for a multifaceted approach that enhances nutritional knowledge while addressing access barriers. Future research should integrate qualitative perspectives to deepen our understanding of these challenges and inform interventions aimed at improving maternal and neonatal health outcomes. Furthermore, the study did not consider potential confounders like other health conditions or socioeconomic status and genetic background. Additionally, the dataset lacked information on smoking status, past history of GDM, and type 2 diabetes, which was noted as a limitation that may have impacted the results. Other limitations include the modest sample size and the focus on specific neonatal outcomes.

This study highlights the significance of addressing FI during pregnancy, as it is associated with increased risks of GDM, PIH, and neonatal complications. Healthcare professionals should identify food-insecure pregnant women, offer support and interventions to improve their dietary intake, and collaborate with community resources.

In conclusion, this cross-sectional study highlights the detrimental effects of FI on GDM, PIH, and maternal outcomes. The mediating role of the DDS in this association underlines the significance of promoting dietary diversity to mitigate the adverse consequences of FI during pregnancy. Future research should focus on longitudinal studies to confirm these findings and explore potential interventions aimed at improving dietary quality and reducing FI among pregnant women. By addressing FI and promoting dietary diversity, healthcare professionals and policymakers can work towards improving pregnancy outcomes and overall health for both mothers and their newborns.

| 1. | Sugiyama T, Saito M, Nishigori H, Nagase S, Yaegashi N, Sagawa N, Kawano R, Ichihara K, Sanaka M, Akazawa S, Anazawa S, Waguri M, Sameshima H, Hiramatsu Y, Toyoda N; Japan Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group. Comparison of pregnancy outcomes between women with gestational diabetes and overt diabetes first diagnosed in pregnancy: a retrospective multi-institutional study in Japan. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103:20-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Srichumchit S, Luewan S, Tongsong T. Outcomes of pregnancy with gestational diabetes mellitus. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;131:251-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | McElwain CJ, Tuboly E, McCarthy FP, McCarthy CM. Mechanisms of Endothelial Dysfunction in Pre-eclampsia and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Windows Into Future Cardiometabolic Health? Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yahaya TO, Salisu T, Abdulrahman YB, Umar AK. Update on the genetic and epigenetic etiology of gestational diabetes mellitus: a review. Egypt J Med Hum Genet. 2020;21:13. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Richards M, Weigel M, Li M, Rosenberg M, Ludema C. Food insecurity, gestational weight gain and gestational diabetes in the National Children's Study, 2009-2014. J Public Health (Oxf). 2021;43:558-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yong HY, Mohd Shariff Z, Mohd Yusof BN, Rejali Z, Tee YYS, Bindels J, van der Beek EM. Higher Parity, Pre-Pregnancy BMI and Rate of Gestational Weight Gain Are Associated with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Food Insecure Women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:2694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Long MA, Gonçalves L, Stretesky PB, Defeyter MA. Food Insecurity in Advanced Capitalist Nations: A Review. Sustainability. 2020;12:3654. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Brandt EJ, Mozaffarian D, Leung CW, Berkowitz SA, Murthy VL. Diet and Food and Nutrition Insecurity and Cardiometabolic Disease. Circ Res. 2023;132:1692-1706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jouanne M, Oddoux S, Noël A, Voisin-Chiret AS. Nutrient Requirements during Pregnancy and Lactation. Nutrients. 2021;13:692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Young MF, Ramakrishnan U. Maternal Undernutrition before and during Pregnancy and Offspring Health and Development. Ann Nutr Metab. 2021;76 (Suppl 3):41-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Augusto ALP, de Abreu Rodrigues AV, Domingos TB, Salles-Costa R. Household food insecurity associated with gestacional and neonatal outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ruel MT. Is dietary diversity an indicator of food security or dietary quality? A review of measurement issues and research needs. Food Nutr Bull. 2003;24:231-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Madzorera I, Isanaka S, Wang M, Msamanga GI, Urassa W, Hertzmark E, Duggan C, Fawzi WW. Maternal dietary diversity and dietary quality scores in relation to adverse birth outcomes in Tanzanian women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;112:695-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gholizadeh F, Moludi J, Lotfi Yagin N, Alizadeh M, Mostafa Nachvak S, Abdollahzad H, Mirzaei K, Mostafazadeh M. The relation of Dietary diversity score and food insecurity to metabolic syndrome features and glucose level among pre-diabetes subjects. Prim Care Diabetes. 2018;12:338-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gicevic S, Gaskins AJ, Fung TT, Rosner B, Tobias DK, Isanaka S, Willett WC. Evaluating pre-pregnancy dietary diversity vs. dietary quality scores as predictors of gestational diabetes and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0195103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bickel G, Nord M, Price C, Hamilton W, Cook J. Guide to Measuring Household Food Security, Revised 2000. Mar 2000. [cited 3 August 2024]. Available from: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/337157/?v=pdf. |

| 17. | Li-Zhen L, Yun X, Xiao-Dong Z, Shu-Bin H, Zi-Lian W, Adrian Sandra D, Bin L. Evaluation of guidelines on the screening and diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus: systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e023014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Correction to: Hypertension in Pregnancy: Diagnosis, Blood Pressure Goals, and Pharmacotherapy: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2022;79:e70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Moludi J, Moradinazar M, Hamzeh B, Najafi F, Soleimani D, Pasdar Y. Depression Relationship with Dietary Patterns and Dietary Inflammatory Index in Women: Result from Ravansar Cohort Study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2020;16:1595-1603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Laraia B, Vinikoor-Imler LC, Siega-Riz AM. Food insecurity during pregnancy leads to stress, disordered eating, and greater postpartum weight among overweight women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23:1303-1311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dibaba Y, Fantahun M, Hindin MJ. The association of unwanted pregnancy and social support with depressive symptoms in pregnancy: evidence from rural Southwestern Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yadegari L, Dolatian M, Mahmoodi Z, Shahsavari S, Sharifi N. The Relationship Between Socioeconomic Factors and Food Security in Pregnant Women. Shiraz E-Med J. 2017;18:e41483. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zarei M, Qorbani M, Djalalinia S, Sulaiman N, Subashini T, Appanah G, Naderali EK. Food Insecurity and Dietary Intake Among Elderly Population: A Systematic Review. Int J Prev Med. 2021;12:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gomez H, DiTosto JD, Niznik CM, Yee LM. Understanding Food Security as a Social Determinant of Diabetes-Related Health during Pregnancy. Am J Perinatol. 2023;40:825-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Smita RM, Shuvo APR, Raihan S, Jahan R, Simin FA, Rahman A, Biswas S, Salem L, Sagor MAT. The Role of Mineral Deficiencies in Insulin Resistance and Obesity. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2022;18:e171121197987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gharachorlo M, Mahmoodi Z, Kabir K, Sharifi N. The Relationship between Food Insecurity and Lifestyle in Women with Gestational Diabetes. J Clin Diagn Res. 2018;12:QC14-QC17. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zareei S, Homayounfar R, Naghizadeh MM, Ehrampoush E, Rahimi M. Dietary pattern in pregnancy and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2018;12:399-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Mutisya M, Ngware MW, Kabiru CW, Kandala N. The effect of education on household food security in two informal urban settlements in Kenya: a longitudinal analysis. Food Sec. 2016;8:743-756. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Mello JA, Gans KM, Risica PM, Kirtania U, Strolla LO, Fournier L. How is food insecurity associated with dietary behaviors? An analysis with low-income, ethnically diverse participants in a nutrition intervention study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:1906-1911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zhang Y, Lu X. A Comprehensive Evaluation of Food Security in China and Its Obstacle Factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;20:451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Beltrán S, Pharel M, Montgomery CT, López-Hinojosa IJ, Arenas DJ, DeLisser HM. Food insecurity and hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0241628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Laraia BA. Food insecurity and chronic disease. Adv Nutr. 2013;4:203-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 280] [Cited by in RCA: 383] [Article Influence: 29.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Torrens C, Poston L, Hanson MA. Transmission of raised blood pressure and endothelial dysfunction to the F2 generation induced by maternal protein restriction in the F0, in the absence of dietary challenge in the F1 generation. Br J Nutr. 2008;100:760-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Behrooz M, Vaghef-Mehrabany E, Moludi J, Ostadrahimi A. Are spexin levels associated with metabolic syndrome, dietary intakes and body composition in children? Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;172:108634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |