Published online Dec 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i12.112789

Revised: September 29, 2025

Accepted: October 29, 2025

Published online: December 15, 2025

Processing time: 131 Days and 20.2 Hours

Epigenetic regulation of leptin (LEP) plays a critical role in metabolic disorders, yet its promoter methylation patterns in lean diabetic populations remain poorly characterized. Emerging evidence suggests DNA methylation may precede clinical hyperglycemia, offering potential for early risk stratification. While obesity-associated LEP methylation is well-studied, lean Asian populations who exhibit high diabetes prevalence despite lower adiposity, represent an underexplored cohort. This study hypothesizes that LEP promoter methylation in per

To investigate LEP promoter methylation status and its association with serum LEP levels across glycemic states in lean Chinese adults.

We enrolled 392 participants including 120 normoglycemic controls, 94 pre

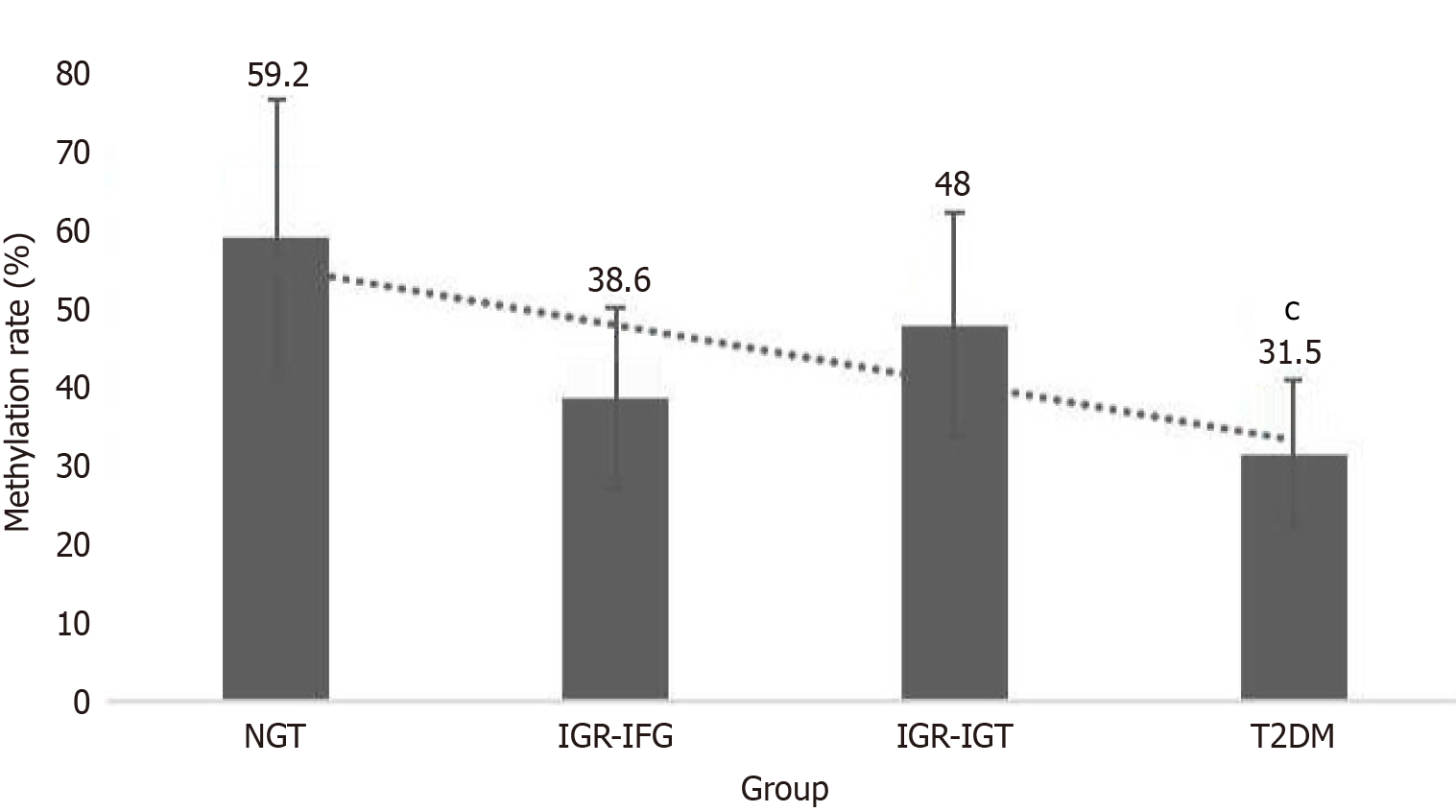

Methylation frequencies declined progressively: 59.2% (controls) reduced to 43.6% (prediabetes; IFG: 38.6%, IGT: 48%) reduced to 31.5% (T2DM) (all P < 0.05 vs controls; T2DM vs IGT: P = 0.030). Serum LEP levels increased significantly in T2DM (16.94 ± 4.19 μg/L) vs controls (11.33 ± 3.10 μg/L; P = 0.002), with intermediate values in prediabetes (IFG: 13.79 ± 3.32 μg/L; IGT: 12.62 ± 4.81 μg/L). A near-perfect inverse correlation between methylation and LEP levels was observed (r = -0.95, 95%CI: -0.97 to -0.92, P < 0.001), persisting after adjusting for age and BMI (β = -0.91, P < 0.001).

LEP promoter hypomethylation parallels worsening glycemic status in lean Chinese adults, suggesting its potential as a blood-based epigenetic biomarker for diabetes progression, pending validation in longitudinal cohorts.

Core Tip: This study reveals progressive hypomethylation of the leptin (LEP) gene promoter in peripheral leukocytes of relatively lean Chinese adults (body mass index < 24 kg/m2) across glycemic states: (1) Normoglycemia (59.2%); (2) Prediabetes (43.6%); and (3) Type 2 diabetes mellitus (31.5%). The methylation decline correlated inversely with serum LEP levels (r = -0.95, P < 0.001), suggesting epigenetic dysregulation precedes metabolic dysfunction independent of obesity. These findings position LEP promoter methylation as a potential blood-based biomarker for early diabetes risk stratification in lean populations, highlighting its clinical utility for preventive strategies.

- Citation: Sun SQ, Liang SZ, Huang Q, Sun JZ. Methylation status of leptin gene promoter in relatively lean Chinese adults with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes 2025; 16(12): 112789

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v16/i12/112789.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i12.112789

Diabetes mellitus has emerged as a global health crisis, with its pathogenesis involving complex interactions between genetic predisposition and environmental factors. The epigenetic basis of diabetes was first proposed by Maier and Olek[1], who established DNA methylation as a crucial regulatory mechanism in disease development. Contemporary re

The leptin (LEP) gene encodes a pleiotropic adipokine that orchestrates multiple metabolic processes[3] through: (1) Central appetite regulation via hypothalamic signaling; (2) Enhancement of energy expenditure through sympathetic activation; (3) Inhibition of adipogenesis in white adipose tissue; and (4) Modulation of pancreatic β-cell function.

While extensive research has characterized LEP methylation patterns in obesity[4,5], its role in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) – particularly in lean populations and prediabetic states – remains understudied. This knowledge gap is clinically relevant because: (1) LEP resistance frequently coexists with insulin resistance in T2DM pathogenesis; (2) Epigenetic modifications may precede clinical hyperglycemia[6]; and (3) Lean diabetic phenotypes [body mass index (BMI) < 24 kg/m2] may exhibit distinct epigenetic signatures[7]. This addresses a gap in understanding epigenetic dysregulation independent of adiposity.

The current investigation addresses critical unanswered questions: (1) How LEP promoter methylation patterns vary across the glycemic spectrum [convert normal glucose tolerance (NGT) to impaired glucose regulation (IGR) to T2DM]; (2) Whether methylation changes correlate with serum LEP concentrations[8]; and (3) How these relationships manifest in relatively lean populations[9].

This research provides novel insights into epigenetic mechanisms underlying diabetes development, with potential applications for: (1) Early risk stratification using blood-based epigenetic markers; (2) Monitoring responses to lifestyle interventions; and (3) Targeted prevention strategies for high-risk populations.

Peripheral blood samples were randomly collected from 94 patients with IGR, 178 patients with T2DM, and 120 volunteers with NGT from Department of Endocrinology, Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University. All participants provided informed consent for the testing procedures. This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and national ethical guidelines. The diagnosis of IGR and T2DM was based on the criteria established by the World Health Organization in 1999, and patients with type 1 diabetes, T2DM with acute complications (ketoacidosis, hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state), malignant diseases (cancer, cachexia, etc.), severe heart, brain, and kidney diseases, moderate to severe liver and kidney impairment, pancreatic damage, or other stress responses were excluded. Additionally, age, BMI, similar diets, and participation in moderate daily physical exercise were included as selection criteria.

DNA extraction kits were obtained from Shanghai Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. The EZ-DNA Methylation-Gold Kit was purchased from Zymo Research (United States). Hot-start DNA polymerase (TaKaRa Taq HS, Japan) and 20 bp DNA molecular weight standards were purchased from TaKaRa (Japan). Primers were synthesized by Shanghai Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. The Human Leptin Quantitative ELISA Kit was obtained from Shanghai Senxiong Technology Industry Co., Ltd.

Sample collection: After meeting the blood collection criteria, all patients and controls had 3 mL of blood collected from the median cubital vein in a seated position after fasting in the morning. The blood was collected into ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid anticoagulant tubes and stored in a -20 °C refrigerator.

Genomic DNA extraction: The extraction was performed following the manufacturer’s protocol, with an A260/A280 ratio between 1.7 and 2.0 for all samples. The DNA samples were stored at -20 °C for future use.

Bisulfite modification and purification of DNA: Take 14 µL of the extracted DNA sample and follow the instructions in the DNA methylation modification kit strictly. Perform bisulfite modification on the genomic DNA of the samples, with 10 specimens in each group and 2 specimens selected for sequencing validation. Convert all unmethylated cytosines in the modified DNA sequence to uracil. Store the DNA solution at -20 °C.

Obtaining positive control DNA: Draw 3 mL of peripheral blood from a healthy volunteer, extract 8 µL of genomic DNA, add 2.5 µL of CpG methylase (M.SssI) and S-adenosylmethionine, along with buffer to a 50 µL system, and incubate at 37 °C for 4 hours. Perform methylation modification using the EZ-DNA Methylation™ Kit and store the DNA solution at -20 °C.

Methylation-specific PCR and electrophoresis analysis: Methylation-specific PCR (MSP) and unmethylation-specific primer pairs (Table 1) were designed to semi-quantitatively assess CpG methylation in the LEP promoter region of LEP gene [(chr7: 127884135-127884240) 23]. MSP was selected for its clinical feasibility, cost-effectiveness, and proven reliability in detecting methylation differences. While bisulfite sequencing offers single-CpG resolution, MSP provides robust semi-quantitative data suitable for cohort comparisons. Droplet digital PCR was employed to validate the methylation quantification results obtained from MSP. DNA samples (4 μL) were bisulfite-modified using 10 μL reagent to distinguish methylated (C to T) and unmethylated cytosines. The PCR reaction system was 25 µL, consisting of 2.5 µL of 10 × PCR buffer (Mg2 + plus), 2 µL of dNTP mixture (each at 2.5 mmol/L), 1/2 µL each of methylated and non-methylated upstream and downstream primers (10 pmol/L), 0.5 µL of hot-start Taq enzyme (5 U/L), 4 µL of modified DNA template, and sterile double-distilled water added to a total volume of 25 µL. The PCR reaction conditions were as follows: (1) Initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 minutes; (2) Denaturation at 95 °C for 30 seconds; (3) Annealing at 62 °C (for methylated primers) or 60 °C (for non-methylated primers) for 1 minute; (4) Extension at 72 °C for 1 minute; (5) For a total of 35 cycles; and (6) Followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 10 minutes. Simultaneously, normal human peripheral blood DNA modified by methylation enzyme was amplified as a methylated positive control, and sterile double-distilled water was used in place of the processed DNA template as a negative control. PCR amplicons were purified using QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) to remove primer dimers and residual nucleotides, with elution in 50 μL EB buffer. DNA concentration was determined by Image J analysis of ethidium bromide-stained gels (accuracy ± 5%). Products were separated on 2% agarose gels containing 0.5 μg/mL ethidium bromide at 100 V for 30 minutes, followed by ultraviolet visualization.

| Primer name primers sequence (5' to 3') | Annealing temperature (°C) | Primer length (bp) | |

| Methylation | Upstream: TTGGCGTTTAGGGTCGTC | 62 | 106 |

| Downstream: AACTCCGCGAAACGAACT | |||

| Non-methylation | Upstream: TTTTTGGTGTTTAGGGTTGTT | 60 | 112 |

| Downstream: AAAAACTCCACAAAACAAACT | |||

Measurement of plasma LEP levels: The serum LEP levels were measured using a double-antibody sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, following the instructions strictly.

Data were systematically analyzed and presented as mean ± SD following rigorous verification of normal distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test (P > 0.05). For categorical variables, intergroup differences were evaluated through χ² tests, while continuous variables were compared using analysis of variance, with all reported P values being Bonferroni-corrected to account for multiple comparisons. To examine potential associations between study variables, linear regression models were employed, with all analyses being preceded by confirmation of data normality. Correlations were assessed via Pearson’s r values after verifying normality. Bonferroni-adjusted P values are reported. The complete statistical workflow was implemented in Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 26.0 (IBM Corp.), employing a conventional two-tailed significance level of α = 0.05 for all hypothesis testing. This comprehensive approach ensured robust statistical evaluation while maintaining appropriate control for type I error.

The methylation status of the LEP gene promoter was systematically analyzed across three glycemic groups (Figure 1). Methylation frequencies exhibited a progressive decline from normoglycemic controls (NGT: 59.2%, 95%CI: 53.7%-64.7%) to prediabetes (IGR: 43.6%, 95%CI: 38.1%-49.1%) and T2DM (31.5%, 95%CI: 26.8%-36.2%).

The statistics for the number of methylated cases are presented in Table 2. Statistical comparisons revealed: (1) T2DM vs NGT: χ² = 22.499, P < 0.001; odds ratio = 0.31 (95%CI: 0.21-0.46); (2) IGR vs NGT: χ² = 5.109, P = 0.024; (3) Impaired fasting glucose (IFG) subgroup vs NGT: χ² = 5.457, P = 0.019; and (4) T2DM vs impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) subgroup: χ² = 4.688, P = 0.030.

| Clinical classification | Number of cases (n) | Leptin gene methylation | Methylation rate (%) |

| Positive (complete/incomplete), negative | |||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 178 | 56 (21/35), 122 | 31.5a,b,c |

| Impaired glucose regulation | 94 | 41 (16/25), 53 | 43.6d |

| Impaired fasting glucose | 44 | 17 (7/10), 27 | 38.6e |

| Impaired glucose tolerance | 50 | 24 (11/13), 26 | 48 |

| Normal glucose tolerance | 120 | 71 (32/39), 49 | 59.2 |

The non-overlapping confidence intervals between T2DM and NGT groups (31.5% vs 59.2%) strongly support the biological significance of this methylation gradient. Notably, the T2DM group demonstrated 3.2-fold lower odds of methylation compared to NGT controls.

These findings suggest that LEP promoter methylation status may serve as a potential biomarker for diabetes progression in lean populations. The consistent methylation pattern across glycemic states warrants further investigation into its clinical utility for early risk stratification.

Serum LEP levels exhibited significant variation across glycemic states (F = 11.49, P < 0.001), with T2DM patients demonstrating markedly elevated concentrations (16.94 ± 4.19 μg/L) compared to normoglycemic controls (11.33 ± 3.10 μg/L; q = 6.81, P < 0.01), while prediabetic individuals displayed intermediate values (IFG: 13.79 ± 3.3 μg/L; IGT: 12.62 ± 4.81 μg/L). Notably, the study groups showed comparable baseline characteristics including age (mean range: 46.7-49.4 years), BMI (21.19-23.23 kg/m2), hypertension prevalence (21.7%-34%), and smoking rates (20.5%-26.7%), with no statistically significant differences observed (all P > 0.05), suggesting that the observed LEP dysregulation occurs independently of these traditional metabolic risk factors in this lean population (BMI < 24 kg/m2) (Table 3).

| Impaired glucose regulation | Type 2 diabetes mellitus | Normal glucose tolerance | |

| Impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance | |||

| Number (male/female) | 44 (20/24), 50 (26/24) | 178 (88/90) | 120 (60/60) |

| Age (years) | 49.4 ± 6.2, 47.2 ± 6.3 | 47.5 ± 5.5 | 46.7 ± 7.4 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.37 ± 2.66, 23.23 ± 3.52 | 22.99 ± 2.53 | 21.19 ± 3.42 |

| Leptin (μg/L) | 13.79 ± 3.32, 12.62 ± 4.81 | 16.94 ± 4.19a | 11.33 ± 3.10 |

| Hypertension (%) | 12 (27.3), 17 (34) | 41 (23.1) | 26 (21.7) |

| Smoking (%) | 9 (20.5), 12 (26) | 44 (24.7) | 27 (22.5) |

Linear regression analysis revealed a progressive increase in LEP levels as DNA methylation incidence decreased. A robust inverse correlation was observed between LEP levels and methylation status. Unadjusted correlation: r = -0.95 (95%CI: -0.97 to -0.92, P < 0.001), indicating a near-perfect negative association. Adjusted analysis: After controlling for age and BMI, the association remained significant (β = -0.91, P < 0.001), suggesting methylation-independent effects on LEP regulation.

IGR is classified into IFG and IGT based on fasting and post-load blood glucose levels. Both conditions can coexist and are referred to as "prediabetes", representing an intermediate state between normal glucose homeostasis and diabetic hyperglycemia. According to the 2010 diabetes epidemiology survey in China, the prevalence rates of prediabetes and diabetes were as high as 15.5% and 9.7%, respectively. IGR is one of the major risk factors for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases as well as the progression to clinical diabetes[9]. The incidence of metabolic syndrome, which comprises T2DM, obesity, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, is showing an increasing trend in the Chinese population. Epigenetic regulation plays a non-negligible role in these syndromes[9]. Diabetes, as a syndrome of energy metabolism disorder, is mainly characterized by peripheral insulin resistance and varying degrees of insulin secretion insufficiency, accompanied by hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and LEP metabolism dysregulation[10], which are involved in the occurrence and progression of its complications.

The expression of LEP protein can be regarded as a marker of adipocyte differentiation and maturation. During the process of preadipocytes differentiating into mature adipocytes, the methylation level of the LEP gene promoter gradually decreases, leading to enhanced gene expression[11,12] and increased LEP content. This study confirms the trend of increasing LEP levels as the incidence of DNA methylation decreases, with a significant negative correlation between LEP levels and the incidence of DNA methylation (r = -0.95, P < 0.001). Consequently, mature adipocytes begin to secrete LEP, participating in the regulation of energy metabolism balance in the body[5,13]. Research by Caspar-Bauguil et al[8] demonstrated that, among obese women undergoing a low-carbohydrate diet intervention, successful weight losers had lower baseline methylation levels of the LEP gene compared to others, suggesting that this methylation status could guide future individual weight loss plans. In experiments with diet-induced obese rats, changes in DNA methylation levels were accompanied by increases in LEP mRNA and serum LEP levels[5]. Bouchard's study on pregnant women with poorly controlled gestational diabetes mellitus found that alterations in the methylation status of the maternal LEP gene led to demethylation of the fetal LEP gene, increasing fetal LEP mRNA and LEP protein expression, thereby elevating the long-term incidence of T2DM in the fetus[14]. These studies all indicate that changes in LEP gene methylation are involved in the progression of obesity and diabetes, suggesting that epigenetic mechanisms, represented by DNA methylation, may play a crucial role in the development of diabetes.

Our study demonstrates decreasing LEP promoter methylation from normoglycemia (59.2%) to prediabetes (43.6%) and T2DM (31.5%) in lean Chinese adults (BMI < 24 kg/m2). This extends prior obesity-focused methylation research[5,6] to non-obese populations, filling a critical knowledge gap given Asia's high diabetes prevalence among lean individuals. The inverse correlation between methylation and serum LEP (r = -0.95, P < 0.001) suggests epigenetic involvement in metabolic dysregulation. The high inverse correlation (r = -0.95) mirrors findings in obese cohorts, suggesting methylation tightly regulates LEP expression in lean individuals. While the strong correlation aligns with mechanistic studies showing LEP’s transcriptional sensitivity to promoter methylation[5,13], its magnitude may reflect cohort homogeneity (narrow BMI range) and MSP’s amplification bias. Prior studies[8,14] in obese cohorts report similar trends (r = -0.82 to -0.79), supporting biological plausibility. Unlike obese cohorts[8], our lean subjects show steeper methylation declines, suggesting adiposity-independent epigenetic dysregulation. Our cross-sectional data reveal an association, not causation, between hypomethylation and hyperleptinemia. Longitudinal studies are needed to establish temporal relationships.

Due to the interplay between genetic and environmental factors in epigenetic regulation, various factors such as age[15], diet and obesity[5,16], stress response[17], physical exercise[18], hyperglycemia, and hyperlipidemia can all influ

This study primarily focused on IFG/IGT and T2DM patients, observing alterations in the DNA methylation status of the LEP gene and the expression of LEP protein. Compared to IGR, T2DM patients exhibited a decreased methylation incidence (χ² = 3.962, P = 0.047), with a statistically significant difference particularly when compared to IGT patients (χ² = 4.688, P = 0.030). Our findings could enable early identification of high-risk individuals via blood-based methylation profiling. For example, Caspar-Bauguil et al[8] demonstrated that baseline LEP methylation predicts dietary intervention responses[14]. Additionally, demethylating agents like 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine[5] warrant exploration in preclinical models. These changes can aid in early screening and prediction of high-risk populations for diabetes. Given the reversibility and heritability of epigenetic changes[20], appropriate interventions (diet, exercise, medication, etc.) can delay the progression of T2DM to a certain extent, stabilize or halt the advancement of IFG/IGT, which holds great clinical significance. Preventing and treating the manifestation of clinical diabetes and the occurrence and progression of long-term cardiovascular complications are crucial.

This study demonstrates a progressive decline in LEP promoter methylation from normoglycemia (59.2%) to prediabetes (43.6%) and T2DM (31.5%) in lean Chinese adults (BMI < 24 kg/m2), accompanied by a significant inverse correlation with serum LEP levels (r = -0.95, P < 0.001). After controlling for age and BMI, the association remained significant (β = -0.91, P < 0.001), suggesting methylation-independent effects on LEP regulation. These findings suggest that epigenetic dysregulation of the LEP gene may contribute to metabolic dysfunction independent of adiposity, offering potential as a blood-based biomarker for diabetes risk stratification in lean populations.

This study demonstrates that LEP promoter methylation status may serve as an early epigenetic marker for diabetes progression in lean individuals, particularly those with prediabetes or T2DM, highlighting its potential clinical relevance for risk stratification. Mechanistically, the strong inverse correlation between hypomethylation and elevated serum LEP levels underscores the role of epigenetic modifications in LEP dysregulation, independent of obesity. However, the cross-sectional design limits causal inferences, and the tissue-specific nature of methylation patterns (peripheral blood vs adipose tissue) necessitates further investigation to validate these findings. Prospective cohort studies are needed to validate these findings and explore interventions targeting LEP methylation (lifestyle modifications or demethylating agents). Additionally, integrating multi-omics approaches (bisulfite sequencing) could enhance the precision of methylation profiling. This work underscores the importance of epigenetic mechanisms in diabetes pathogenesis beyond traditional obesity-associated models, highlighting avenues for personalized prevention strategies in lean populations.

| 1. | Maier S, Olek A. Diabetes: a candidate disease for efficient DNA methylation profiling. J Nutr. 2002;132:2440S-2443S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Barrès R, Osler ME, Yan J, Rune A, Fritz T, Caidahl K, Krook A, Zierath JR. Non-CpG methylation of the PGC-1alpha promoter through DNMT3B controls mitochondrial density. Cell Metab. 2009;10:189-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 480] [Cited by in RCA: 477] [Article Influence: 28.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 3. | Münzberg H, Heymsfield SB, Berthoud HR, Morrison CD. History and future of leptin: Discovery, regulation and signaling. Metabolism. 2024;161:156026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Milagro FI, Campión J, García-Díaz DF, Goyenechea E, Paternain L, Martínez JA. High fat diet-induced obesity modifies the methylation pattern of leptin promoter in rats. J Physiol Biochem. 2009;65:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yokomori N, Tawata M, Onaya T. DNA demethylation modulates mouse leptin promoter activity during the differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells. Diabetologia. 2002;45:140-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lavery WJ, Barski A, Wiley S, Schorry EK, Lindsley AW. KMT2C/D COMPASS complex-associated diseases [K(CD)COM-ADs]: an emerging class of congenital regulopathies. Clin Epigenetics. 2020;12:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yang W, Lu J, Weng J, Jia W, Ji L, Xiao J, Shan Z, Liu J, Tian H, Ji Q, Zhu D, Ge J, Lin L, Chen L, Guo X, Zhao Z, Li Q, Zhou Z, Shan G, He J; China National Diabetes and Metabolic Disorders Study Group. Prevalence of diabetes among men and women in China. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1090-1101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2186] [Cited by in RCA: 2326] [Article Influence: 145.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 8. | Caspar-Bauguil S, Cousin B, Bour S, Casteilla L, Penicaud L, Carpéné C. Erratum to: Adipose tissue lymphocytes: types and roles. J Physiol Biochem. 2011;67:497. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shen J, Goyal A, Sperling L. The emerging epidemic of obesity, diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome in china. Cardiol Res Pract. 2012;2012:178675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kieffer TJ, Habener JF. The adipoinsular axis: effects of leptin on pancreatic beta-cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000;278:E1-E14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Miranda TB, Jones PA. DNA methylation: the nuts and bolts of repression. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:384-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 473] [Cited by in RCA: 477] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Clouaire T, Stancheva I. Methyl-CpG binding proteins: specialized transcriptional repressors or structural components of chromatin? Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1509-1522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pena-Leon V, Perez-Lois R, Villalon M, Prida E, Muñoz-Moreno D, Fernø J, Quiñones M, Al-Massadi O, Seoane LM. Novel mechanisms involved in leptin sensitization in obesity. Biochem Pharmacol. 2024;223:116129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bouchard L, Thibault S, Guay SP, Santure M, Monpetit A, St-Pierre J, Perron P, Brisson D. Leptin gene epigenetic adaptation to impaired glucose metabolism during pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2436-2441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kominato R, Fujimoto S, Mukai E, Nakamura Y, Nabe K, Shimodahira M, Nishi Y, Funakoshi S, Seino Y, Inagaki N. Src activation generates reactive oxygen species and impairs metabolism-secretion coupling in diabetic Goto-Kakizaki and ouabain-treated rat pancreatic islets. Diabetologia. 2008;51:1226-1235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Campión J, Milagro FI, Martínez JA. Individuality and epigenetics in obesity. Obes Rev. 2009;10:383-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Franco R, Schoneveld O, Georgakilas AG, Panayiotidis MI. Oxidative stress, DNA methylation and carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2008;266:6-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 408] [Cited by in RCA: 423] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | McGee SL, Hargreaves M. Exercise and skeletal muscle glucose transporter 4 expression: molecular mechanisms. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2006;33:395-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shehab MJ, Al-Mofarji ST, Mahdi BM, Ameen RS, Al-Zubaidi MM. The correlation between obesity and leptin signaling pathways. Cytokine. 2025;192:156970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Godfrey KM, Lillycrop KA, Burdge GC, Gluckman PD, Hanson MA. Epigenetic mechanisms and the mismatch concept of the developmental origins of health and disease. Pediatr Res. 2007;61:5R-10R. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 450] [Cited by in RCA: 367] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/