Published online Dec 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i12.112580

Revised: September 5, 2025

Accepted: November 6, 2025

Published online: December 15, 2025

Processing time: 137 Days and 18.6 Hours

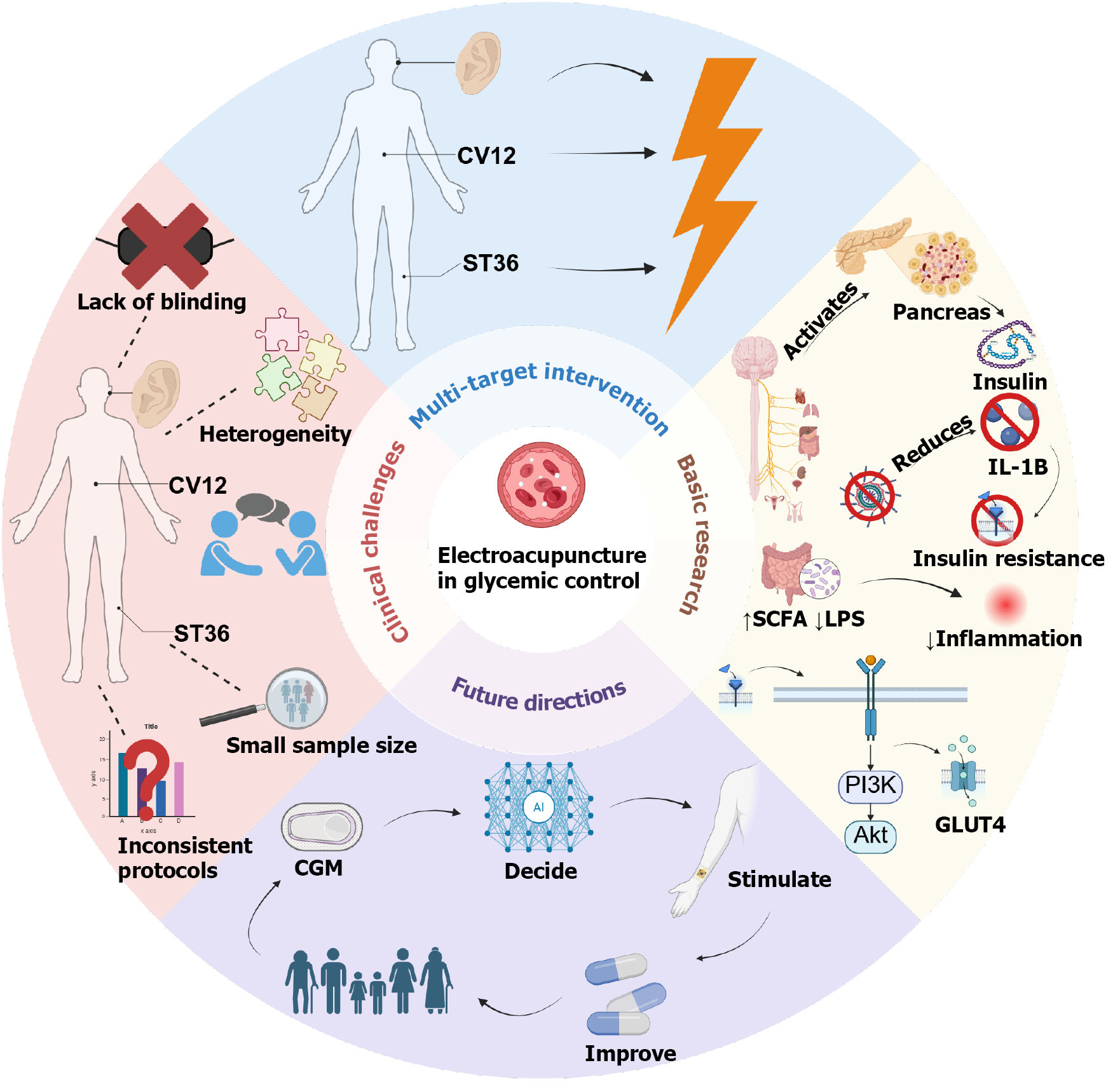

Diabetes is a major global metabolic disorder, with the type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) population in China expected to reach 168 million by 2050. Electroacupuncture (EA) and auricular acupuncture represent safe, accessible, and multi-targeted strategies for glycemic control with strong translational potential. Cli

Core Tip: This review examines electroacupuncture (EA) for glycemic control, addressing clinical controversies and underlying mechanisms. While EA shows promise in reducing blood glucose levels in type 2 diabetes, current clinical trials are limited by small sample sizes and heterogeneous designs, lacking robust international consensus. Basic research indicates that EA’s hypoglycemic effects involve modulating the neuro-endocrine-immune axis, enhancing insulin signaling, and improving gut microbiota. Future work should focus on optimizing EA protocols and developing standardized interventions to advance its clinical application in diabetes management.

- Citation: Wang SY, Deng CX, Huang YN, Tian MX, Zhuang SY, Deng YF, Xu B, Xu TC. Electroacupuncture in glycemic control: Transitioning from clinical controversies to potential basic research. World J Diabetes 2025; 16(12): 112580

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v16/i12/112580.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i12.112580

Diabetes mellitus, as the most prevalent chronic metabolic disease worldwide, exhibits a yearly escalation in incidence and complication burden. In China, the number of individuals aged 20-79 years with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is expected to reach 168 million by 2050[1]. Recently, non-pharmacological interventions, particularly electroacupuncture (EA), have garnered attention for their potential in regulating glucose metabolism due to their ease of use and minimal side effects. Clinical studies demonstrate that needling at trunk and limb acupoints can significantly reduce fasting blood glucose (FBG) and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels in patients with type 2 diabetes[2,3], while auricular acupuncture, owing to its convenience for self-management, is widely utilized in regions such as Europe, the Americas, and Australia, with multiple clinical reports supporting its hypoglycemic effects[4]. Nevertheless, its underlying mechanisms warrant further elucidation. Variability in study designs, small sample sizes, and insufficient randomization and blinding hinder the integration of conclusions across studies[5]. Additionally, many systematic reviews highlight the lack of large-scale, multicenter, rigorously bias-controlled randomized controlled trials (RCTs), preventing EA's efficacy from achieving broad international consensus[6]. Therefore, in-depth investigation of EA's neuro-endocrine mechanisms not only facilitates a scientific evaluation of its effectiveness but also provides theoretical foundational support for future multi

In contrast, mechanistic studies primarily utilizing experimental animals such as rats have fully demonstrated the scientific value and future potential of EA in hyperglycemia, with multiple independent teams[7] respectively reporting that EA at Zusanli (ST36) or Tianshu (ST25) acupoints can reduce blood glucose levels in diabetic animals, with mecha

Despite the fact that the existing evidence is not yet sufficient to establish a unified consensus, EA and auricular acupuncture have demonstrated considerable potential as safe, accessible, and multi-targeted strategies for glycemic control. This review first recapitulates the controversies and criticisms in clinical research; subsequently summarizes the progress in basic research on EA for hyperglycemia, including characteristics of animal models, experimental designs, primary intervention acupoints, and therapeutic effects; then discusses the differences in acupoint selection between clinical and basic research and the underlying reasons; and finally proposes potential future directions in mechanistic research on auricular and body acupuncture, with the aim of providing insights for the standardization of EA in blood glucose management and the integration of acupuncture into modern science. The target audience of this study includes clinicians and researchers involved in diabetes management and treatment, as well as scholars and professionals interested in non-pharmacological interventions for diabetes.

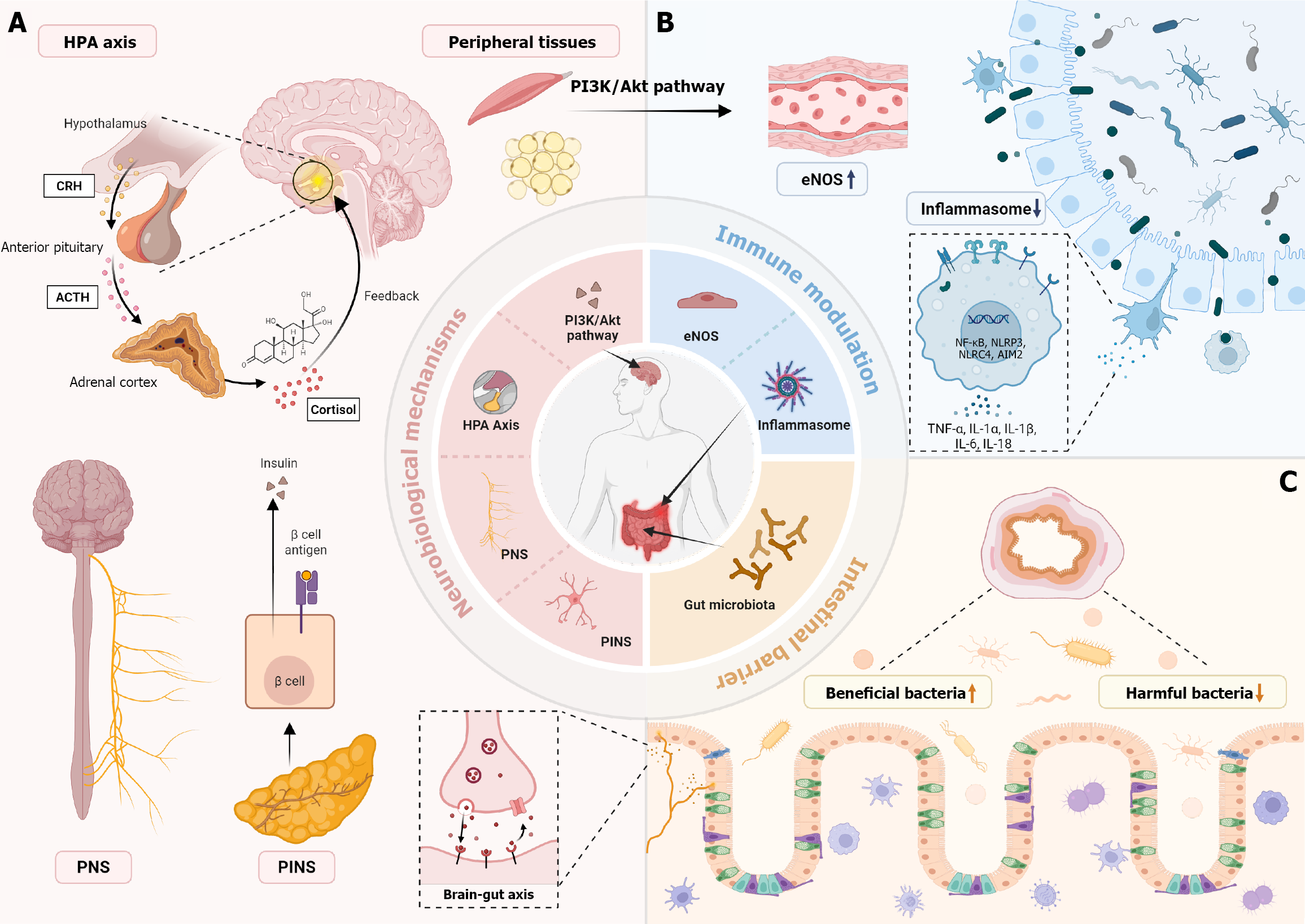

Body acupoints refer to acupoints located on any part of the human body, including the head, face, abdomen, back, waist, etc. (excluding the ear)[9], while auricular acupoints refer to acupoints distributed on the auricle[10]; these stimulation sites exert hypoglycemic effects from different perspectives. Acupuncture practitioners commonly employ body acupoints on the trunk and limbs, such as Zusanli (ST36) and Sanyinjiao (SP6)[11], as well as auricular targets like the pancreas area and endocrine area to assist in blood glucose reduction. Research by Lee et al[12] demonstrated that EA at ST36 (15 Hz, 30 minutes) enhances the muscle insulin receptor substrate (IRS)-1/AKT signaling pathway by stimulating the parasympathetic nervous system (with atropine completely blocking the hypoglycemic effect), thereby reducing blood glucose. For auricular acupoints, Guo et al[13] indicated that auricular vagus nerve stimulation can regulate autonomic nerves via the nucleus tractus solitarius to activate pancreatic β-cells, promoting insulin secretion and inhibiting glucagon release. Empirical studies also show that interventions at auricular acupoints such as AH6a, TF4, and AT4 can improve glucose metabolism. A meta-analysis by Yu et al[14] of 14 studies revealed that auricular acupressure combined with conventional treatment significantly reduced FBG, 2-hour postprandial blood glucose, and HbA1c in T2DM patients, while also improving lipid profiles and body mass index (BMI); through data mining, they identified AH6a, TF4 (endocrine), AT4, CO18, and CO10 as key auricular acupoints related to the regulation of the pancreas and digestive system. A meta-analysis by Hua et al[15] of 22 studies indicated that auricular acupuncture has significant effects in reducing fasting serum insulin levels and homeostasis model assessment insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), with its primary mechanism likely involving stimulation of the auricular vagus nerve to modulate autonomic nerves, which in turn improve pancreatic islet function and subsequently regulate insulin.

Existing research indicates that EA at specific acupoints has a significant short-term hypoglycemic effect, but its efficacy as a long-term management strategy for T2DM lacks support from high-quality evidence. Several RCTs have already evaluated the short-term effects of EA on blood glucose, with commonalities among these studies including: (1) Similar single-session durations: Clinical experiments using 30-minute stimulation periods on different body acupoints, all resulting in significant reductions in blood glucose levels; (2) Meta-analyses (all concerning EA) collectively demon

Overall, clinical research on EA for hyperglycemia exhibits the following major issues: (1) Insufficient sample sizes (most studies involve only around 20 patients); (2) Methodological deficiencies; and (3) Inability to conduct double-blind experiments, resulting in uneven methodological quality. Due to substantial variations in inclusion and exclusion criteria, the available clinical trials exhibit high heterogeneity, making it inappropriate to perform a reliable meta-analysis. Multiple systematic reviews have identified recurrent flaws in acupuncture RCTs, including unclear or inadequate randomization, lack of blinding, and small sample sizes[20], which severely limit the strength of conclusions. Through re-evaluation of relevant system evaluations, it was found that most RCTs have low quality, with common deficiencies including lack of registration schemes, incomplete searches, and high risk of bias[21]. The quality of clinical evidence for EA therapy in diabetes management is dually constrained by its technical complexity and methodological limitations. The unique characteristics of EA therapy determine the heterogeneity of its outcomes and the controversies surrounding placebo effects. Many acupuncture studies “lack rigorous design (e.g., inadequate control groups, insufficient blinding), which restricts the reproducibility and generalizability of the results”. Different studies often employ sham EA (without current output), simple acupuncture, or conventional medications (e.g., oral hypoglycemic agents) as control groups. While this diversity enriches study designs, it further exacerbates outcome heterogeneity and perpetuates debates over placebo effects. Fundamentally, EA requires precise regulation of stimulation parameters (frequency, intensity, waveform), and practitioners must adjust these settings based on real-time feedback from both acupoint sensation and patient physiology (e.g., blood glucose fluctuations). This necessity makes true double-blind implementation extremely challenging, particularly in blinding the acupuncturist. It represents a core methodological barrier: Operator awareness of allocation may unconsciously influence point selection or stimulation settings [e.g., Zusanli (ST36) + Sanyinjiao (SP6) combination], thereby introducing performance bias and potentially exaggerating or diminishing observed hypoglycemic effects. This blinding limitation not only reduces the internal validity of the studies but may also lead to external validity issues: In clinical practice, the hypoglycemic effects of EA often depend on the practitioner's experience and the patient's immediate physiological feedback; if studies cannot simulate a true double-blind environment, the generalizability of their results to diabetic patient populations is compromised. From the perspective of evidence grading, such design flaws may lead to the downgrading of the evidence for EA in lowering blood glucose (e.g., low or very low quality in the GRADE system), thereby affecting its recommendation strength in diabetes clinical guidelines, for example, rendering it incomparable to standard hypoglycemic drugs (e.g., metformin). RCTs remain the gold standard to address most of these methodological deficits, as they enable proper randomization and control for confounding factors. However, even within randomized designs, the nature of EA often restricts feasible blinding to single-blind approaches. For example, due to program limitations, most RCTs of EA for insomnia could only be conducted using a single blind method. This methodological weakness, however, could be addressed through the adoption of standardized research protocols. It is recom

EA therapy possesses unique advantages. EA enables personalized treatment protocols through precise regulation of electrical parameters, which to some extent compensates for the shortcomings of traditional acupuncture; moreover, compared to the hypoglycemia risks associated with hypoglycemic drugs such as insulin, the side effects of EA are minimal. For example, EA can adjust stimulation intensity and frequency according to individual patient differences, thereby better inducing hypoglycemic responses. Additionally, EA therapy demonstrates good tolerability and safety in clinical practice, with few adverse reactions, providing strong support for its application in diabetes management[22]. In the future, innovative methods can be employed to mitigate current limitations, such as adopting patient blinding combined with objective biomarker assessments (e.g., continuous glucose monitoring or inflammatory marker levels), or introducing automated EA devices to minimize practitioner bias. Simultaneously, strengthening the design of mul

While clinical studies often employ multi-acupoint protocols to enhance therapeutic efficacy through synergistic effects, basic research tends to focus on single-acupoint stimulation to isolate specific mechanisms. This methodological diver

Basic research on EA for hyperglycemia is primarily conducted in animals; understanding the characteristics of these animal models helps us comprehend the differences in the hypoglycemic effects of EA on humans and animals. Current models can relatively comprehensively reflect the damage to various organs under diabetic conditions. In the past five years, research on EA for hyperglycemia has mainly employed two types of models: First, the T2DM model induced by high-fat diet (HFD) combined with low-dose STZ, which more closely approximates the characteristics of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, and is commonly used to evaluate the improvement of insulin sensitivity by EA[24]. Genetic models such as Diabetic (db/db) mice possess advantages like spontaneous hyperglycemia and rapid progre

| Model name | Number of published articles in WoS and PubMed (from the database to the present) | Number of published electroacupuncture articles in WoS and PubMed | Acupoints | Major references | Ref. |

| HFD + STZ; T2DM | 15200 | 68 | Tianshu (ST25) (88%), Zusanli (ST36) | Hypoglycemic effect of electroacupuncture | [3] |

| Diabetic (db/db) mice | 8300 | 52 | Yishu (EX-B3) (79%), Zusanli (ST36) (76%) | Electroacupuncture at Yishu (EX-B3) promotes β-cell regeneration via modulating pancreatic innervation in type 2 diabetic db/db mice | [26] |

Although animal experiments provide abundant mechanistic evidence for EA in hyperglycemia, high caution is warranted when extrapolating these results to clinical settings due to biases arising from interspecies differences. These differences are primarily manifested in three aspects: First, inherent differences in pancreatic islet structure and function. Rodents have a significantly higher proportion of pancreatic islet β-cells (75%-80%) compared to humans (50%-60%), with α-cells exhibiting peripheral distribution (whereas they are intermixed in humans), leading to species-specific insulin/glucagon secretion responses following EA[27]; second, differences in neuro-endocrine pathway sensitivity. Rodents are more sensitive to stimulation of the hepatic branch of the abdominal vagus nerve, while humans have a denser distribution of the auricular vagus nerve; the temporal dynamics of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis feedback regulation differ markedly between rats (corticosterone half-life of 20 minutes) and humans (cortisol half-life of 60-90 minutes), affecting the evaluation of EA's anti-stress effects[28]; third, effects of metabolic rate and body size scaling. Mice have a basal metabolic rate approximately several times that of humans[29], whereas larger animals (e.g., pigs, dogs) more closely approximate human physiology. For instance, in the spontaneously diabetic minipig - a large-animal model whose pancreatic innervation and metabolic scaling more closely approximate human physiology - EA at ST36 must be delivered at 0.5 mA (continuous square wave, 5-10 Hz) to elicit a hypoglycaemic decrement equivalent to that observed in rodents at markedly lower current densities. This quantitative discrepancy underscores the necessity of species-specific calibration of electrical dose, rather than direct extrapolation of stimulation parameters validated in small-animal studies.

In basic research, the focus of studies on EA intervention strategies centers on classical acupoints, stimulation parameters, and the synergistic effects exerted by the combined use of multiple acupoints (i.e., multi-acupoint superiority over single-acupoint). Electrical stimulation of classical acupoints such as Zusanli (ST36) and Zhongwan (CV12) has been confirmed to stably reduce FBG, with mechanisms closely related to β-endorphin release and opioid receptor activation. Regarding stimulation parameters, commonly used frequencies are concentrated between 2-15 Hz, with waveforms primarily consisting of continuous waves or dilatational waves; single-session stimulation durations are typically 30-60 minutes, and treatment courses often span 2-4 weeks. Additionally, a few studies have explored the combined application of EA with oral hypoglycemic agents (e.g., acarbose), finding synergistic enhancements in reducing blood glucose and improving insulin curves. However, current research also exposes key issues, such as inconsistencies in EA parameter standards and insufficient control group designs, which severely impact the horizontal comparability and experimental reproducibility of results; these are critical directions for future optimization of intervention strategies (Tables 2 and 3)[30-34].

| Stimulation frequency and current intensity | Waveform | Acupoints | Treatment duration | Ref. |

| 2 Hz, 1 mA | Continuous | Zusanli (ST36) | 20 minutes/session, once daily for 4 weeks | [30] |

| 2 Hz, 1 mA | Continuous | Zhongwan (CV12), Zusanli (ST36), Guanyuan (CV4), Fenglong (ST40) | 15 minutes/session, every other day for 8 weeks | [26] |

| 10 Hz, 2 mA | Continuous | Zhongwan (CV12) | 30 minutes/session, every other day for 3 weeks | [3] |

| 15 Hz, 1-2 mA | Continuous | Zusanli (ST36), Zhongwan (CV12) | 20-30 minutes/session, once daily for 4 weeks | [12] |

| 2-10 Hz, 1.5-2 mA, 100 Hz, 3 mA | Sparse-dense wave, interrupted wave | Tianshu (ST25), Zusanli (ST36), Shenshu (BL23) | 30 minutes/session, every other day for 3 weeks | [3] |

| 10 Hz, 1-3 mA | Sparse-dense wave | Tianshu (ST25) | 30 minutes/session, once daily for 2 weeks | [2] |

| Species | Diabetic state | Acupoints (bilateral or unilateral) | Frequency (Hz) | Duration | Current (mA) | Effect description | Mechanism research conclusion | Ref. |

| Rat | Type 1 diabetes (fasted) | Zusanli (ST36) (ST36, bilateral) | 15 | 30-60 minutes | - | Reduces fasting blood sugar | Activates vagus nerve-liver axis: Enhances parasympathetic activity, promotes glycogen synthesis in liver and inhibits gluconeogenesis | [31] |

| Type 1 diabetes (STZ induced) | Zusanli (ST36) (ST36, bilateral) | 15 | 30/60 minutes | - | Enhances insulin signaling protein expression, significantly lowers blood sugar | Modulates IRS-1/AKT pathway: Stimulates vagus nerve to release acetylcholine, activating insulin signaling pathways in skeletal muscle and liver | [32] | |

| Type 2 diabetes (fasted) | Zusanli (ST36) (ST36, bilateral) | 2 | 20 minutes | 1 | Reduces blood sugar | Inhibits hypothalamic inflammation: Modulates HPA axis, reduces corticosterone levels, alleviates inflammation and improves insulin resistance | [33] | |

| Type 2 diabetes (HFD + low-dose STZ induced) | Zusanli (ST36), Pishu (BL20), bilateral | 15 | 30 minutes per session, once per day for 14 days | 1 | Significantly improves insulin sensitivity | Reshapes gut microbiota: Increases SCFA-producing bacteria, reduces LPS levels, alleviates systemic inflammation, improves insulin sensitivity | [25] | |

| Mouse | Normal (fasted) | Zusanli (ST36), bilateral | 15 | 30 minutes | - | Reduces blood sugar | Activates cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway: Enhances vagus nerve activity, inhibits splenic TNF-α release, reduces inflammation | [24] |

| Type 2 diabetes (HFD) | Guanyuan (CV4) + Zhongwan (CV12), bilateral | 3 | 30 minutes | - | Significantly lowers postprandial blood sugar | Activates cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway: Enhances vagus nerve activity, inhibits splenic TNF-α release, reduces inflammation | [34] | |

| Type 2 diabetes (STZ induced) | Zusanli (ST36), bilateral | 10 | 30 minutes per day, for 8 weeks | 1-3 | Lowers random blood sugar and fasting blood sugar | Promotes β-cell regeneration: Modulates PINS, activates β-cell proliferation signals (e.g., PDX-1), inhibits pancreatic fibrosis | [2] |

Existing mechanistic studies have revealed key pathways through which EA exerts its role in blood glucose control, with neurobiological mechanisms and anti-inflammatory pathways being the focal points of research; these findings primarily originate from animal experiments stimulating body acupoints rather than auricular acupoints, and most target single acupoints such as ST25, ST36, CV12, and CV4. First, in terms of neurobiological mechanisms, EA demonstrates significant regulatory capacity on the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which is considered one of the core components of its hypoglycemic effects. Studies have found that EA at specific acupoints (e.g., Zhongwan CV12, Tianshu ST25) can enhance parasympathetic nervous activity (particularly the vagus nerve), improve local tissue blood circulation and glucose utilization, thereby contributing to blood glucose reduction. Further research indicates that EA stimulation of specific acupoints, such as Yishu (EX-B3), can directly regulate the pancreatic intrinsic nerves (PINS), thereby improving pancreatic β-cell function, promoting normal insulin secretion or improving its efficacy, and achieving the goal of blood glucose reduction; by modulating the HPA axis, it reduces levels of stress hormones such as cortisol, corrects endocrine disruptions, and indirectly exerts beneficial effects on glucose metabolism. Concurrently, studies suggest that EA can activate intracellular insulin signaling pathways, such as the PI3K/Akt pathway, enhancing glucose uptake and uti

Second, anti-inflammatory pathways are also one of the primary mechanisms through which EA exerts its hypogly

In summary, mechanistic research on EA for hyperglycemia has made significant progress at the animal experiment level, revealing its multi-target and multi-pathway characteristics. Current evidence strongly supports that EA primarily achieves blood glucose control through complex neurobiological regulation (involving the ANS, PINS, HPA axis, and insulin signaling pathways, among others) as well as effective anti-inflammatory pathways (including inhibition of inflammasomes, modulation of cytokine networks, and improvement of gut microbiota) (Figure 2 and Table 4)[38-40].

| Specific mechanism | Supporting evidence | Relevant acupoints | Experimental subjects | Ref. |

| HPA axis regulation | Reduces adrenal corticosteroids (such as cortisol), improves endocrine disorders | Yishu (EX-B3) | T2DM rats | [3] |

| Anti-inflammatory pathway | Inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation, reduces IL-1β, improves chronic inflammation | Non-specific | STZ-induced diabetic rats, HFD high-fat diet mice, db/db genetically diabetic mice, OLETF obese diabetic rats | [12] |

| Neurobiological mechanism | Enhances parasympathetic nerve (e.g., vagus nerve) activity, improves local circulation and glucose consumption | Zhongwan (CV12), Tianshu (ST25), etc. | OLETF rats | [38] |

| Gut microbiota and inflammation control | Increases SCFAs, reduces circulating LPS levels, lowers systemic inflammation | Zhongwan (CV12), Tianshu (ST25), Zusanli (ST36) | T2DM model | [26] |

| Insulin signaling pathway activation | Activates PI3K/Akt pathway, enhances GLUT2 and GCK mRNA expression, reduces fasting insulin levels | Zusanli (ST36), Shenshu (BL23) | T2DM rats | [3] |

| ta-VNS | Stimulates auricular vagus nerve via projections from the vagus nerve (ABVN) to the NTS, affects the concentration changes of the neurotransmitters noradrenaline, GABA and ACh in the central nervous system | Non-specific | Humans, SD rats | [39,40] |

The stimulation targets of auricular acupuncture are localized to the auricle, which contains a rich neural distribution, particularly the auricular branch of the vagus nerve - the only cutaneous sensory branch of the vagus nerve. Mechanistically, converging evidence from human neuroimaging and physiological studies indicates that cymba conchae stimulation engages brainstem autonomic nuclei, notably the nucleus tractus solitarius, and exerts a causal influence on cardiovagal outflow, providing a direct pathway from auricular input to central autonomic control relevant to glycemic regulation[41]. Auricular acupuncture or auricular acupressure can induce vagal tone, potentially regulating cardio

Although these preliminary evidences highlight the clinical potential of auricular acupuncture in the field of hyper

To overcome these bottlenecks, it is necessary to develop more precise acupoint mapping technologies and unified stimulation protocols, thereby bridging the gap between basic research and clinical practice. We propose progress in three areas: Localization, parameters, and translation. First, establish a standardized auricular acupoint localization system by constructing a 3D atlas of neurovascular structures, supported by VR/AR navigation and wearable products using surface scanning, skin impedance, or high-frequency ultrasound, to ensure reproducible and individualized acupoint selection. Second, formulate unified stimulation prescriptions and reporting standards (frequency, pulse width, duty cycle, intensity upper limits, and treatment courses), and develop wearable auricular vagus stimulation devices with closed-loop parameter adjustment capabilities, utilizing objective indicators such as skin impedance, heart rate varia

Supported by basic research, EA therapy and body acupoint therapy have been widely applied in the clinical management of blood glucose control in diabetes. Clinical studies indicate that traditional multi-acupoint EA protocols, while capable of achieving significant therapeutic effects, may result in lower patient compliance due to the complexity of the treatment regimens. Therefore, researchers and clinicians have begun exploring ways to reduce the number of acupoints used while ensuring therapeutic efficacy, thereby enhancing treatment convenience and patient adherence. Taking T2DM as an example, traditional acupuncture protocols often employ multi-acupoint combined interventions, focusing on acupoints along the spleen and stomach meridians and those related to metabolic regulation, such as Zusanli (ST36), Zhongwan (CV12), Sanyinjiao (SP6), Shenshu (BL23), and Neiguan (PC6), aimed at improving digestive and absorptive functions, promoting energy metabolism, enhancing bodily immunity, and regulating endocrine functions. Notably, some treatment protocols, building on traditional acupuncture, further integrate composite therapies such as EA, auricular acupuncture (e.g., selecting auricular concha secretion point, pancreaticobiliary area), and acupoint thread embedding; such multi-target comprehensive treatments not only enhance efficacy but also help reduce the number of acupoints.

Additionally, researchers can draw inspiration from advances in basic research, deriving insights from core pathways and circuits of EA in glucose control to optimize and streamline treatment acupoints. Multiple basic studies have confirmed that using a limited number of high-efficiency acupoints for EA can achieve therapeutic effects comparable to those of traditional multi-acupoint protocols within a shorter time frame. This strategy simplifies the treatment process, reduces patient burden, and significantly improves adherence. At the same time, it facilitates the clinical translation of basic research findings. In clinical practice, the aforementioned approaches to reducing EA acupoint application are typically used in combination, thereby forming effective synergies and enhancing clinical efficacy. By optimizing treat

Guided by foundational neuroscience research, a key strategy for refining acupuncture protocols in diabetes involves streamlining acupoint selection based on mechanistic insights. This can be achieved by merging acupoints that share common spinal segment innervation. The concept of a “spinal segment” originates from the neuroanatomical theory of “segmental innervation”, which posits that specific spinal segments (e.g., thoracic T1-T12, lumbar L1-L5) provide neural supply to their corresponding dermatomes (skin regions) and myotomes, thereby transmitting sensory, motor, and autonomic neural impulses[51]. Histological analyses and imaging studies have revealed that acupoints exhibit widespread and anatomically specific neural projections in the brain, forming neural circuits that participate in fundamental physiological functions[52]. Notably, acupoints can be mapped to defined spinal segmental neural projections - for instance, acupoints on the lower limbs are typically associated with the lumbosacral spinal cord. Therefore, by merging acupoints within the same spinal segment - combining those innervated by the same or adjacent spinal segments - it is possible to synergistically activate shared spinal reflex arcs and related neural pathways, thereby enhancing stimulation efficiency and avoiding redundancy. For example, integrating lower limb acupoints such as Zusanli (ST36) and Sanyinjiao (SP6) - which correspond to the neuronal networks of the L4-S1 segments - can activate shared reflex arcs and cover multiple metabolic pathways without redundant stimulation, as studies show that spinal segmental organization allows a single input to elicit multiple output reflexes, thereby optimizing peripheral neural integration[53]. Similarly, prioritizing acupoints with well-elucidated neurophysiological pathways relies on neuroi

The convergence of acupuncture principles with advanced bioengineering is paving the way for intelligent, personalized glycemic management tools. Basic research utilizing high-resolution neuroimaging (e.g., functional magnetic resonance imaging) can map brain network dynamics elicited by acupoint stimulation, clarifying how electrical parameters precisely modulate the HPA axis and vagal pathways. This provides a data-driven foundation for personalized protocols[58]. Simultaneously, artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms can analyze real-time physiological streams - such as CGM data and heart rate variability (HRV) - to simulate multimodal neural feedback. This enables the optimization of key stimulation parameters - including frequency (e.g., 2-15 Hz), intensity (e.g., 0.5-2 mA), and duration - based on objective physiological feedback, moving beyond empirical adjustment to maximize anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitizing effects[59]. Building on this, the development of closed-loop wearable devices represents a significant advancement. Existing technical prototypes, such as smart earpieces employing taVNS or limb patches utilizing transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation (TEAS), are being designed to monitor physiological signals (e.g., skin impedance, simplified EEG/EMG) and dynamically adjust stimulation parameters within predefined safety limits[60,61]. Conceptualized future technology forms envision fully integrated systems where AI-driven algorithms automatically titrate stimulation parameters in real-time based on CGM-derived feedback signals (e.g., time in range trends, glucose rate of change) and other physiological indicator thresholds (e.g., HRV indices). The aim is to create adaptive closed-loop circuits that precisely target core neural modules (e.g., vagus nerve branches), enhancing hypoglycemic durability and patient adherence while minimizing side effects[62].

The "medicine-health maintenance integration" model seeks to translate optimized auricular stimulation into viable adjunctive methods to pharmacological therapy for home-based glycemic management. Clinical studies on acupuncture adjunctive to glucose-lowering drugs have shown promising results in improving glycemic indicators, although the evidence level requires further strengthening by larger, rigorous trials[63]. This model facilitates the development of user-friendly devices (e.g., smart earpieces for taVNS) for home use, applying low-intensity stimulation (e.g., 2-10 Hz, 0.5-1 mA) to key auricular points (e.g., AH6a, TF4, Shenmen). When used adjunctively with standard oral hypoglycemic agents (e.g., metformin), these interventions aim to enhance synergistic effects and potentially reduce medication dependency. Supported by education and mobile health apps, users can adjust stimulation based on real-time CGM feedback, enabling individualized management. This approach bridges clinical oversight with home-based self-care, incorporates safety models, and mitigates over-medicalization risks[64]. Promoting these home-based protocols involves integrating wearable technology with pharmacotherapy into closed-loop systems. Evidence suggests that non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation in home settings may reduce HbA1c and, via long-term neuro-endocrine regulation, potentially lower diabetes complication risks[65]. This approach suits middle-aged and elderly patients, emphasizing prevention and shifting care from hospitals to communities. Multicenter trials indicate that combining this stimulation with drugs can reduce blood sugar levels by 20%-30%, achieving significant synergistic effects and providing a sustainable, low-cost solution[66]. Crucially, promoting these devices necessitates comprehensive risk mitigation. Safety mechanisms (e.g., parameter ceilings, auto-shutoff), clear guidance, and remote medical support for data monitoring and personalized adjustments are essential to prevent over-stimulation or misuse, thereby ensuring safety and compliance[67]. If suc

In conclusion, EA and auricular acupuncture show substantial potential as non-pharmacological interventions for blood glucose regulation in individuals with T2DM. Both therapies have demonstrated significant short-term benefits, with evidence supporting their hypoglycemic effects via multiple mechanisms, including modulation of the autonomic nervous system, enhancement of insulin sensitivity, and anti-inflammatory pathways. However, clinical research continues to be hindered by methodological challenges, including small sample sizes, insufficient blinding, and heterogeneity in study designs, which hinder the ability to generalize findings and establish long-term efficacy[68]. Basic research has played a pivotal role in elucidating the neurobiological and anti-inflammatory mechanisms underlying EA’s effects, offering valuable insights for optimizing acupuncture protocols. Notably, the integration of single-acupoint studies with clinical multi-acupoint applications could lead to more standardized and effective treatments, enhancing both therapeutic efficacy and patient adherence. Furthermore, advancements in wearable technology and AI-driven systems promise to revolutionize the integration of acupuncture into diabetes management by providing real-time, personalized adjustments to treatment parameters based on physiological feedback. Despite the promising findings, further large-scale, multicenter, randomized controlled trials are essential to validate the long-term efficacy and establish standardized treatment protocols. Ultimately, bridging the gap between basic research and clinical application, while optimizing treatment parameters and acupoint selection, could pave the way for incorporating acupuncture as a mainstream adjunctive therapy in diabetes care, potentially alleviating the growing public health burden of diabetes.

| 1. | International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes Atlas. 11th ed. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, 2025: 47. |

| 2. | An J, Wang L, Song S, Tian L, Liu Q, Mei M, Li W, Liu S. Electroacupuncture reduces blood glucose by regulating intestinal flora in type 2 diabetic mice. J Diabetes. 2022;14:695-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Liu XX, Zhang LZ, Zhang HH, Lai LF, Wang YQ, Sun J, Xu NG, Li ZX. Low-frequency electroacupuncture improves disordered hepatic energy metabolism in insulin-resistant Zucker diabetic fatty rats via the AMPK/mTORC1/p70S6K signaling pathway. Acupunct Med. 2022;40:360-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Boccino J. Auricular Acupuncture for Lowering Blood Glucose in Type 2 Diabetes: A Pilot Study. Med Acupunct. 2023;35:186-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kann JR. Acupuncture Not Supported By Strong Scientific Evidence. Am Fam Physician. 2020;101:326-328. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Lu L, Zhang Y, Tang X, Ge S, Wen H, Zeng J, Wang L, Zeng Z, Rada G, Ávila C, Vergara C, Tang Y, Zhang P, Chen R, Dong Y, Wei X, Luo W, Wang L, Guyatt G, Tang C, Xu N. Evidence on acupuncture therapies is underused in clinical practice and health policy. BMJ. 2022;376:e067475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Xu T, Yu Z, Liu Y, Lu M, Gong M, Li Q, Xia Y, Xu B. Hypoglycemic Effect of Electroacupuncture at ST25 Through Neural Regulation of the Pancreatic Intrinsic Nervous System. Mol Neurobiol. 2022;59:703-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dong S, Zhao L, Liu J, Sha X, Wu Y, Liu W, Sun J, Su Y, Zhuang Z, Chen J, Dong Y, Xie B, Zhou A, Ji H, Wang Y, Deng X, Jing X, Ma Q, Wang N, Liu S. Neuroanatomical organization of electroacupuncture in modulating gastric function in mice and humans. Neuron. 2025;113:3243-3259.e11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang M, Liu W, Ge J, Liu S. The immunomodulatory mechanisms for acupuncture practice. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1147718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Li Q, Chen Y, Pang Y, Kou L, Lu D, Ke W. An AAM-Based Identification Method for Ear Acupoint Area. Biomimetics (Basel). 2023;8:307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang LQ, Chen Z, Zhang K, Liang N, Yang GY, Lai L, Liu JP. Zusanli (ST36) Acupoint Injection for Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Altern Complement Med. 2018;24:1138-1149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Lee YC, Li TM, Tzeng CY, Chen YI, Ho WJ, Lin JG, Chang SL. Electroacupuncture at the Zusanli (ST-36) Acupoint Induces a Hypoglycemic Effect by Stimulating the Cholinergic Nerve in a Rat Model of Streptozotocine-Induced Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:650263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Guo K, Lu Y, Wang X, Duan Y, Li H, Gao F, Wang J. Multi-level exploration of auricular acupuncture: from traditional Chinese medicine theory to modern medical application. Front Neurosci. 2024;18:1426618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yu Y, Xiang Q, Liu X, Yin Y, Bai S, Yu R. Auricular pressure as an adjuvant treatment for type 2 diabetes: data mining and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;15:1424304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hua K, Usichenko T, Cummings M, Bernatik M, Willich SN, Brinkhaus B, Dietzel J. Effects of auricular stimulation on weight- and obesity-related parameters: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Front Neurosci. 2024;18:1393826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kumar R, Mooventhan A, Manjunath NK. Immediate Effect of Needling at CV-12 (Zhongwan) Acupuncture Point on Blood Glucose Level in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Pilot Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 2017;10:240-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mooventhan A, Ningombam R, Nivethitha L. Effect of bilateral needling at an acupuncture point, ST-36 (Zusanli) on blood glucose levels in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: A pilot randomized placebo controlled trial. J Complement Integr Med. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Liu C, Ao Y, Liu B, Huang J, Wang Q, Ao X, Wang X, Ban X. The safety and efficacy of acupuncture in treating nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis based on randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore). 2025;104:e42272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Li SQ, Chen JR, Liu ML, Wang YP, Zhou X, Sun X. Effect and Safety of Acupuncture for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of 21 Randomised Controlled Trials. Chin J Integr Med. 2022;28:463-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | McDonald JL, Bauer M. Is Electroacupuncture Contraindicated for Preventing and Treating Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy? Med Acupunct. 2023;35:290-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Li T, Yan J, Hu J, Liu X, Wang F. Efficacy and safety of electroacupuncture for carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS): A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Surg. 2022;9:952361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Han Y, Lu Z, Chen S, Gao T, Gang X, Pan T, Meng M, Liu M. Effect of electroacupuncture on glucose and lipid metabolism in type 2 diabetes: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e27762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sang P, Zhao J, Yang H. The efficacy of electroacupuncture in among early diabetic patients with lower limb arteriosclerotic wounds. Int Wound J. 2024;21:e14526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Manlai U, Chang SW, Lee SC, Ho WJ, Hsu TH, Lin JG, Lin CM, Chen YI, Chang SL. Hypoglycemic Effect of Electroacupuncture Combined with Antrodia cinnamomea in Dexamethasone-Induced Insulin-Resistant Rats. Med Acupunct. 2021;33:58-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yang YJ, Zhou XC, Tian HR, Liang FX. Electroacupuncture relieves type 2 diabetes by regulating gut microbiome. World J Diabetes. 2025;16:103032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Huang Q, Chen R, Peng M, Li L, Li T, Liang FX, Xu F. [Effect of electroacupuncture on SIRT1/NF-κB signaling pathway in adipose tissue of obese rats]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2020;40:185-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Cabrera O, Berman DM, Kenyon NS, Ricordi C, Berggren PO, Caicedo A. The unique cytoarchitecture of human pancreatic islets has implications for islet cell function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2334-2339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 862] [Cited by in RCA: 921] [Article Influence: 46.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Finnerup NB, Kuner R, Jensen TS. Neuropathic Pain: From Mechanisms to Treatment. Physiol Rev. 2021;101:259-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 962] [Article Influence: 160.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Diaz-Cuadros M, Miettinen TP, Skinner OS, Sheedy D, Díaz-García CM, Gapon S, Hubaud A, Yellen G, Manalis SR, Oldham WM, Pourquié O. Metabolic regulation of species-specific developmental rates. Nature. 2023;613:550-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zhuang S, Liu S, Li R, Duan H. Electroacupuncture alleviates insulin resistance and impacts the hypothalamic IRS-1/PI3K/AKT pathway and miRNA-29a-3p in a rat model of type 2 diabetes. Acupunct Med. 2025;43:104-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Peplow PV, Baxter GD. Electroacupuncture for control of blood glucose in diabetes: literature review. J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 2012;5:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Man KM, Lee YC, Chen YI, Chen YH, Chang SL, Huang CC. Electroacupuncture at Bilateral ST36 Acupoints: Inducing the Hypoglycemic Effect through Enhancing Insulin Signal Proteins in a Streptozotocin-Induced Rat Model during Isoflurane Anesthesia. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021;2021:5852599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Zhang S, Cui Y, Sun ZR, Zhou XY, Cao Y, Li XL, Yin HN. Research progress on the mechanism of acupuncture on type Ⅱ diabetes mellitus. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu. 2024;49:641-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Yin J, Kuang J, Chandalia M, Tuvdendorj D, Tumurbaatar B, Abate N, Chen JD. Hypoglycemic effects and mechanisms of electroacupuncture on insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2014;307:R332-R339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Feng Y, Fang Y, Wang Y, Hao Y. Acupoint Therapy on Diabetes Mellitus and Its Common Chronic Complications: A Review of Its Mechanisms. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:3128378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Li N, Guo Y, Gong Y, Zhang Y, Fan W, Yao K, Chen Z, Dou B, Lin X, Chen B, Chen Z, Xu Z, Lyu Z. The Anti-Inflammatory Actions and Mechanisms of Acupuncture from Acupoint to Target Organs via Neuro-Immune Regulation. J Inflamm Res. 2021;14:7191-7224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 35.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 37. | Zhang L, Chen X, Wang H, Huang H, Li M, Yao L, Ma S, Zhong Z, Yang H, Wang H. "Adjusting Internal Organs and Dredging Channel" Electroacupuncture Ameliorates Insulin Resistance in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus by Regulating the Intestinal Flora and Inhibiting Inflammation. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2021;14:2595-2607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Ding SS, Hong SH, Wang C, Guo Y, Wang ZK, Xu Y. Acupuncture modulates the neuro-endocrine-immune network. QJM. 2014;107:341-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Butt MF, Albusoda A, Farmer AD, Aziz Q. The anatomical basis for transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation. J Anat. 2020;236:588-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 357] [Article Influence: 51.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 40. | He W, Jing XH, Zhu B, Zhu XL, Li L, Bai WZ, Ben H. The auriculo-vagal afferent pathway and its role in seizure suppression in rats. BMC Neurosci. 2013;14:85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Toschi N, Duggento A, Barbieri R, Garcia RG, Fisher HP, Kettner NW, Napadow V, Sclocco R. Causal influence of brainstem response to transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation on cardiovagal outflow. Brain Stimul. 2023;16:1557-1565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | He W, Wang X, Shi H, Shang H, Li L, Jing X, Zhu B. Auricular acupuncture and vagal regulation. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:786839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Müller SJ, Teckentrup V, Rebollo I, Hallschmid M, Kroemer NB. Vagus nerve stimulation increases stomach-brain coupling via a vagal afferent pathway. Brain Stimul. 2022;15:1279-1289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Yeh CH, Chien LC, Chiang YC, Huang LC. Auricular point acupressure for chronic low back pain: a feasibility study for 1-week treatment. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:383257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Borgmann D, Fenselau H. Vagal pathways for systemic regulation of glucose metabolism. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2024;156:244-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Rong PJ, Zhao JJ, Li YQ, Litscher D, Li SY, Gaischek I, Zhai X, Wang L, Luo M, Litscher G. Auricular acupuncture and biomedical research--A promising Sino-Austrian research cooperation. Chin J Integr Med. 2015;21:887-894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Kaniusas E, Kampusch S, Tittgemeyer M, Panetsos F, Gines RF, Papa M, Kiss A, Podesser B, Cassara AM, Tanghe E, Samoudi AM, Tarnaud T, Joseph W, Marozas V, Lukosevicius A, Ištuk N, Šarolić A, Lechner S, Klonowski W, Varoneckas G, Széles JC. Current Directions in the Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation I - A Physiological Perspective. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 29.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Kiernan JA, Mitchell R. Some observations on the innervation of the pinna of the ear of the rat. J Anat. 1974;117:397-402. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Wirz-Ridolfi A. The History of Ear Acupuncture and Ear Cartography: Why Precise Mapping of Auricular Points Is Important. Med Acupunct. 2019;31:145-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Gao Z, Jia S, Li Q, Lu D, Zhang S, Xiao W. [Deep learning approach for automatic segmentation of auricular acupoint divisions]. Sheng Wu Yi Xue Gong Cheng Xue Za Zhi. 2024;41:114-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Hashmi SS, van Staalduinen EK, Massoud TF. Anatomy of the Spinal Cord, Coverings, and Nerves. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2022;32:903-914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Liang J, Sun W, Zhou Y, Zhang P, Chen Y, Li X, He H, Liu X, Zhou S, Shen J, Jiang H, Chen Y, Tang R, Yan L. Study on the Central Neural Pathways Connecting the Brain and Peripheral Acupoints Using Neural Tracers. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2025;31:e70554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Lo YT, Lam JL, Jiang L, Lam WL, Edgerton VR, Liu CY. Cervical spinal cord stimulation for treatment of upper limb paralysis: a narrative review. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2025;50:781-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Davids M, Guerin B, Klein V, Wald LL. Optimization of MRI Gradient Coils With Explicit Peripheral Nerve Stimulation Constraints. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2021;40:129-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Tian H, Wang Y, Ji Y, Rahman MM. [Fully Automatic Glioma Segmentation Algorithm of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Based on 3D-UNet With More Global Contextual Feature Extraction: An Improvement on Insufficient Extraction of Global Features]. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2024;55:447-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Sugimoto YA, Yadohisa H, Abe MS. Network structure influences self-organized criticality in neural networks with dynamical synapses. Front Syst Neurosci. 2025;19:1590743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Li J, Fei Z, Xie Y, Deng D, Ming X, Niu F. A review of acupoint localization based on deep learning. Chin Med. 2025;20:116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Vachha B, Huang SY. MRI with ultrahigh field strength and high-performance gradients: challenges and opportunities for clinical neuroimaging at 7 T and beyond. Eur Radiol Exp. 2021;5:35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Huang G, Chen X, Liao C. AI-Driven Wearable Bioelectronics in Digital Healthcare. Biosensors (Basel). 2025;15:410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Dimitri P, Savage MO. Artificial intelligence in paediatric endocrinology: conflict or cooperation. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2024;37:209-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Romano M, Fratini A, Gargiulo GD, Cesarelli M, Iuppariello L, Bifulco P. On the Power Spectrum of Motor Unit Action Potential Trains Synchronized With Mechanical Vibration. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2018;26:646-653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Du J, Luo S, Shi P. A Wearable EMG-Driven Closed-Loop TENS Platform for Real-Time, Personalized Pain Modulation. Sensors (Basel). 2025;25:5113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Tryggestad JB, Willi SM. Complications and comorbidities of T2DM in adolescents: findings from the TODAY clinical trial. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29:307-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Tarr AW, Backx M, Hamed MR, Urbanowicz RA, McClure CP, Brown RJP, Ball JK. Immunization with a synthetic consensus hepatitis C virus E2 glycoprotein ectodomain elicits virus-neutralizing antibodies. Antiviral Res. 2018;160:25-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Liu FJ, Wu J, Gong LJ, Yang HS, Chen H. Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation in anti-inflammatory therapy: mechanistic insights and future perspectives. Front Neurosci. 2024;18:1490300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Staats PS, Staats A, Mikhaiel B, Chen J, Azabou E, Rangon CM. Combined minimally invasive vagal cranial nerve and trigeminocervical complex peripheral nerve stimulation produces prolonged improvement of severe painful peripheral neuropathy and hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes. Front Neurosci. 2025;19:1644961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Chen Y. Applying auricular magnetic therapy to decrease blood glucose levels and promote the healing of gangrene in diabetes patients: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2024;18:636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Zhang Z, Li R, Chen Y, Yang H, Fitzgerald M, Wang Q, Xu Z, Huang N, Lu D, Luo L. Integration of traditional, complementary, and alternative medicine with modern biomedicine: the scientization, evidence, and challenges for integration of traditional Chinese medicine. Acupunct Herb Med. 2024;4:68-78. [DOI] [Full Text] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/