Published online Apr 15, 2024. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v15.i4.697

Peer-review started: November 19, 2023

First decision: December 8, 2023

Revised: December 19, 2023

Accepted: February 27, 2024

Article in press: February 27, 2024

Published online: April 15, 2024

Processing time: 144 Days and 14.6 Hours

The importance of age on the development of ocular conditions has been reported by numerous studies. Diabetes may have different associations with different stages of ocular conditions, and the duration of diabetes may affect the deve

To examine associations between the age of diabetes diagnosis and the incidence of cataract, glaucoma, age-related macular degeneration (AMD), and vision acuity.

Our analysis was using the UK Biobank. The cohort included 8709 diabetic participants and 17418 controls for ocular condition analysis, and 6689 diabetic participants and 13378 controls for vision analysis. Ocular diseases were identified using inpatient records until January 2021. Vision acuity was assessed using a chart.

During a median follow-up of 11.0 years, 3874, 665, and 616 new cases of cataract, glaucoma, and AMD, res

The younger age at the diagnosis of diabetes is associated with a larger relative risk of incident ocular diseases and greater vision loss.

Core Tip: This is the first prospective cohort study to examine the association of age at the diagnosis of diabetes with main ocular conditions. Our findings suggest the age at the diagnosis of diabetes plays an important role in the association between diabetes and incident cataract, glaucoma, and age-related macular disease as well as vision. A younger age at the diagnosis of diabetes was associated with larger excessive relative risk for ocular conditions and larger vision loss. Type 1 diabetes appears to have potentially more harmful effects.

- Citation: Ye ST, Shang XW, Huang Y, Zhu S, Zhu ZT, Zhang XL, Wang W, Tang SL, Ge ZY, Yang XH, He MG. Association of age at diagnosis of diabetes with subsequent risk of age-related ocular diseases and vision acuity. World J Diabetes 2024; 15(4): 697-711

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v15/i4/697.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v15.i4.697

Although the age-standardised prevalence of avoidable vision impairment did not change, the global number of cases increased substantially due to the increasing aging population[1]. Cataract, glaucoma, and age-related macular degen

Previous evidence has highlighted the importance of diabetes in the development of ocular conditions[3,4]. Diabetes has been linked to numerous ocular conditions, including cataract[5], glaucoma[6], and AMD[7]. The United Kingdom Million Women Study, involving 1312051 postmenopausal women, demonstrated that diabetes was an important risk factor for cataract surgery[8]. In contrast, evidence suggests diabetes is not among the leading predictors for glaucoma[9,10], and other studies did not find a significant association between diabetes and glaucoma[11]. Previous studies have been inconsistent regarding the association of diabetes with AMD[7]. Several studies have demonstrated a positive rela

The importance of age on the development of ocular conditions has been reported by numerous studies[5,7,9,10]. Diabetes may have different associations with different stages of ocular conditions[19], and the duration of diabetes may affect the development of diabetic eye disease[3]. While there is a dose-response relationship between the age at diagnosis of diabetes and the risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality[20,21], whether the age at diagnosis of diabetes is asso

It is important to identify the life stage at which a diagnosis of diabetes is associated with the highest risk of major ocular conditions for the prevention or screening of these conditions. Using the UK Biobank, we sought to examine the association between age at the diagnosis of diabetes and the incidence of cataract, glaucoma, and AMD.

The UK Biobank is a population-based cohort of more than 500000 participants aged 40-73 years at baseline, recruited between 2006 and 2010 from one of the 22 assessment centres across England, Wales, and Scotland[22]. The design and population of the UK Biobank study have been described in detail elsewhere[22]. The UK Biobank Study’s ethical app

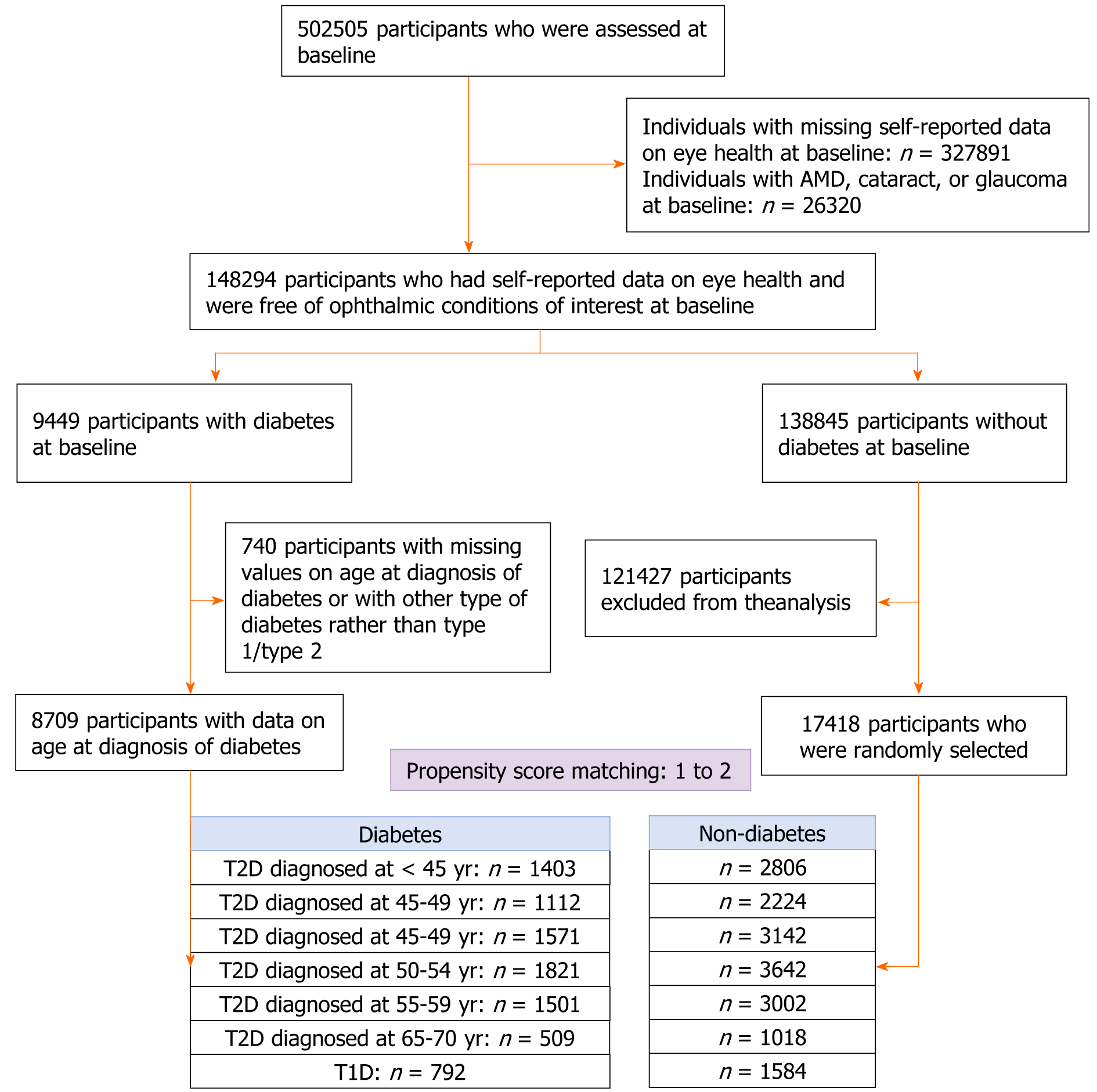

Individuals with missing data on self-reported eye health (n = 327891), or those with ocular diseases (n = 26320) at baseline were excluded from the analysis. After the exclusion of individuals with missing values on the age at the diagnosis of diabetes or with other type of diabetes rather than type 1 diabetes (T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D, n = 264), 7917 participants with T2D were divided into six groups according to the age at diagnosis: < 45, 45-49, 50-54, 55-59, 60-64, and ≥ 65 years. For each diabetic participant, two controls were randomly selected from those without diabetes at baseline using propensity scores matched by age, gender, ethnicity, education, household income, physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption, sleep duration, depression, hypertension, heart disease, stroke, body mass index (BMI), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and triglycerides. This analysis was conducted for each diabetes diagnosis age group. The same method was used to randomly select controls for T1D patients (n = 792, Figure 1).

Among 117252 individuals who had their vision acuity assessed, 7274 had diabetes at baseline. After excluding individuals with missing values on diabetes diagnosis age or with other type of diabetes rather than T1D/T2D (n = 585), 6192 with T2D were divided into six groups according to the diagnosis age: < 45, 45-49, 50-54, 55-59, 60-64, and ≥ 65 years. The same method was used to select controls for individuals with T1D (Supplementary Figure 1).

First, participants were classified as diabetic if they reported that a doctor had ever told them that they had diabetes (Field code: 2443). For those with a self-reported diagnosis of diabetes, they were asked a follow-up question “What was your age when diabetes was first diagnosed?” Participants with a potentially abnormal age at the diagnosis of diabetes were asked to confirm. Algorithms based on self-reported medical history and medication were used to identify T1D and T2D[23]. Furthermore, the codes for international classification diseases (ICD) were used to define T1D/T2D (Supplementary Table 1). The age at the diagnosis of diabetes (years) was then computed by subtracting the birth date from the initial diagnosed date divided by 365.25.

Individuals were classified as having AMD (Field code: 1528), cataract (1278), or glaucoma (1277) if they reported a diagnosis of the corresponding conditions. Cases of ocular conditions were also identified using hospital inpatient records based on ICD codes (Supplementary Table 1). Furthermore, we used surgical procedures by OPCS4 to identify cataract events (codes: C71.2 or C75.1)[24]. The onset date of ocular condition was defined as the earliest recorded code date regardless of source. Person-years were calculated from the date of baseline assessment to the date of onset ocular condition, date of death, or the end of follow-up (December 31, 2020 for England and Wales and January 31, 2021 for Scotland), whichever came first.

The baseline vision acuity examination was performed among a sub-cohort of the UK Biobank from June 2009 to July 2010. The procedure for the vision acuity test has been described in detail elsewhere[25]. Presenting distance vision acuity was measured at 4 m or at 1 m (if a participant was unable to read) using the logarithm of the minimum angle of re

BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. A touchscreen computer was used to collect information, including age, gender, education, income, smoking, alcohol consumption, and sleep duration. Metabolic equivalent-hours/week of physical activity during work and leisure time was estimated using specific que

Hypertension, depression, stroke, and heart disease at baseline were defined based on self-reported data. Glycated hae

T-test was used to test the difference in continuous variables and Chi-square test in categorical variables between diabetic participants and controls in each diabetes diagnosis age group.

The HR with 95%CIs for incident ocular condition associated with T1D and age at diagnosis of T2D was estimated using Cox proportional hazard regression models. The multivariable analysis included adjustment for matching factors (propensity score) and the full model further incorporated concurrent HbA1c. This analysis was separately conducted for incidence of cataract, cataract surgery, glaucoma, and AMD. The analysis was not performed for types of glaucoma or AMD due to their low incidence.

General linear regression models were used to test the difference in LogMAR between diabetic participants and controls for each diagnosis age group. The multivariable analysis included adjustments for matching factors (propensity score). The association between age at the diagnosis of diabetes and intraocular pressure (IOP) was examined using general linear regression models.

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to examine whether the association between age at the diagnosis of T2D and ocular conditions and vision acuity was independent of duration of diabetes. In this analysis, two controls for each T2D patient were randomly selected using propensity score matching based on the same factors as depicted in Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure 1, without stratification by the age at the diagnosis of diabetes. The age at the diagnosis of T2D, treated as a categorical variable (< 45, 45-49, 50-54, 55-59, 60-64, and ≥ 65 years), was analysed to assess the association between the age at the diagnosis of diabetes and ocular conditions and vision acuity.

Missing values for categorical variables were assigned as a single category. Missing values for continuous covariates were imputed with the mean.

Data analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc.), and all P values were two-sided, with statistical significance set at < 0.05.

For ocular condition analysis, 26127 participants (36.9% females) aged 40-70 (mean ± SD: 59.1 ± 8.2) years old were included in the analysis. Diabetic participants had higher HbA1c, and education levels compared to the controls. No significant difference in other characteristics between the two groups were observed (Table 1). Individuals with T1D had higher HbA1c but did not differ in other characteristics compared to the controls (Supplementary Table 2).

| < 45 yr1 | 45-49 yr1 | 50-54 yr1 | 55-59 yr1 | 60-64 yr1 | ≥ 65 yr1 | |||||||

| Non-diabetes | Diabetes | Non-diabetes | Diabetes | Non-diabetes | Diabetes | Non-diabetes | Diabetes | Non-diabetes | Diabetes | Non-diabetes | Diabetes | |

| Age (yr) | 51.9 ± 8.4 | 51.9 ± 7.9 | 54.7 ± 8.6 | 54.7 ± 5.8 | 58.7 ± 7.8 | 58.7 ± 4.8 | 62.2 ± 5.9 | 62.0 ± 3.5 | 65.0 ± 3.6 | 64.9 ± 2.4 | 67.6 ± 2.7 | 67.6 ± 1.4 |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Female | 1032 (36.8) | 506 (36.1) | 743 (33.4) | 400 (36.0) | 1163 (37.0) | 600 (38.2) | 1312 (36.0) | 652 (35.8) | 1075 (35.8) | 541 (36.0) | 402 (39.5) | 202 (39.7) |

| Male | 1774 (63.2) | 897 (63.9) | 1481 (66.6) | 712 (64.0) | 1979 (63.0) | 971 (61.8) | 2330 (64.0) | 1169 (64.2) | 1927 (64.2) | 960 (64.0) | 616 (60.5) | 307 (60.3) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Whites | 1937 (69.0) | 968 (69.0) | 1634 (73.5) | 812 (73.0) | 2522 (80.3) | 1255 (79.9) | 3225 (88.6) | 1600 (87.9) | 2715 (90.4) | 1352 (90.1) | 939 (92.2) | 469 (92.1) |

| Non-whites | 785 (28.0) | 421 (30.0) | 535 (24.1) | 296 (26.6) | 548 (17.4) | 297 (18.9) | 367 (10.1) | 207 (11.4) | 245 (8.2) | 141 (9.4) | 71 (7.0) | 36 (7.1) |

| Unknown | 84 (3.0) | 14 (1.0) | 55 (2.5) | 4 (0.4) | 72 (2.3) | 19 (1.2) | 50 (1.4) | 14 (0.8) | 42 (1.4) | 8 (0.5) | 8 (0.8) | 4 (0.8) |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| 0-5 yr | 863 (30.8) | 379 (27.0) | 640 (28.8) | 266 (23.9) | 839 (26.7) | 397 (25.3) | 907 (24.9) | 436 (23.9) | 650 (21.7) | 318 (21.2) | 206 (20.2) | 105 (20.6) |

| 6-12 yr | 1270 (45.3) | 687 (49.0) | 1108 (49.8) | 597 (53.7) | 1524 (48.5) | 776 (49.4) | 1631 (44.8) | 853 (46.8) | 1368 (45.6) | 681 (45.4) | 419 (41.2) | 202 (39.7) |

| ≥ 13 yr | 567 (20.2) | 292 (20.8) | 421 (18.9) | 225 (20.2) | 706 (22.5) | 361 (23.0) | 1044 (28.7) | 493 (27.1) | 927 (30.9) | 477 (31.8) | 369 (36.2) | 192 (37.7) |

| Missing | 106 (3.8) | 45 (3.2) | 55 (2.5) | 24 (2.2) | 73 (2.3) | 37 (2.4) | 60 (1.6) | 39 (2.1) | 57 (1.9) | 25 (1.7) | 24 (2.4) | 10 (2.0) |

| Household income (pounds) | ||||||||||||

| < 18000 | 680 (24.2) | 418 (29.8) | 575 (25.9) | 320 (28.8) | 846 (26.9) | 470 (29.9) | 1075 (29.5) | 550 (30.2) | 912 (30.4) | 528 (35.2) | 372 (36.5) | 209 (41.1) |

| 18000-30999 | 529 (18.9) | 285 (20.3) | 446 (20.1) | 242 (21.8) | 696 (22.2) | 328 (20.9) | 868 (23.8) | 445 (24.4) | 751 (25.0) | 371 (24.7) | 267 (26.2) | 121 (23.8) |

| 31000-51999 | 535 (19.1) | 244 (17.4) | 420 (18.9) | 211 (19.0) | 576 (18.3) | 273 (17.4) | 600 (16.5) | 297 (16.3) | 454 (15.1) | 218 (14.5) | 110 (10.8) | 55 (10.8) |

| 52000-100000 | 369 (13.2) | 152 (10.8) | 319 (14.3) | 129 (11.6) | 356 (11.3) | 184 (11.7) | 353 (9.7) | 171 (9.4) | 227 (7.6) | 102 (6.8) | 52 (5.1) | 22 (4.3) |

| > 100000 | 101 (3.6) | 44 (3.1) | 67 (3.0) | 25 (2.2) | 80 (2.5) | 34 (2.2) | 99 (2.7) | 42 (2.3) | 55 (1.8) | 17 (1.1) | 14 (1.4) | 5 (1.0) |

| Unknown | 212 (7.6) | 103 (7.3) | 128 (5.8) | 77 (6.9) | 169 (5.4) | 121 (7.7) | 182 (5.0) | 96 (5.3) | 178 (5.9) | 92 (6.1) | 57 (5.6) | 32 (6.3) |

| Not answered | 380 (13.5) | 157 (11.2) | 269 (12.1) | 108 (9.7) | 419 (13.3) | 161 (10.2) | 465 (12.8) | 220 (12.1) | 425 (14.2) | 173 (11.5) | 146 (14.3) | 65 (12.8) |

| Physical activity (MET-minutes/week) | 2287 ± 2162 | 2264 ± 2201 | 2281 ± 2153 | 2223 ± 2176 | 2205 ± 1959 | 2197 ± 2142 | 2350 ± 2204 | 2366 ± 2231 | 2475 ± 2230 | 2376 ± 2188 | 2553 ± 2113 | 2523 ± 2360 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||||||||

| Never | 365 (13.0) | 209 (14.9) | 250 (11.2) | 142 (12.8) | 296 (9.4) | 148 (9.4) | 272 (7.5) | 121 (6.6) | 191 (6.4) | 92 (6.1) | 73 (7.2) | 33 (6.5) |

| Previous | 196 (7.0) | 125 (8.9) | 141 (6.3) | 96 (8.6) | 201 (6.4) | 129 (8.2) | 216 (5.9) | 130 (7.1) | 141 (4.7) | 116 (7.7) | 61 (6.0) | 33 (6.5) |

| Current | 2192 (78.1) | 1063 (75.8) | 1804 (81.1) | 868 (78.1) | 2623 (83.5) | 1288 (82.0) | 3144 (86.3) | 1563 (85.8) | 2662 (88.7) | 1292 (86.1) | 881 (86.5) | 442 (86.8) |

| Missing | 53 (1.9) | 6 (0.4) | 29 (1.3) | 6 (0.5) | 22 (0.7) | 6 (0.4) | 10 (0.3) | 7 (0.4) | 8 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) |

| Smoking | ||||||||||||

| Never | 1549 (55.2) | 831 (59.2) | 1082 (48.7) | 554 (49.8) | 1524 (48.5) | 741 (47.2) | 1605 (44.1) | 779 (42.8) | 1261 (42.0) | 627 (41.8) | 406 (39.9) | 191 (37.5) |

| Former | 846 (30.1) | 366 (26.1) | 783 (35.2) | 380 (34.2) | 1245 (39.6) | 639 (40.7) | 1621 (44.5) | 840 (46.1) | 1472 (49.0) | 728 (48.5) | 511 (50.2) | 274 (53.8) |

| Current | 368 (13.1) | 193 (13.8) | 341 (15.3) | 173 (15.6) | 355 (11.3) | 176 (11.2) | 400 (11.0) | 188 (10.3) | 251 (8.4) | 133 (8.9) | 99 (9.7) | 41 (8.1) |

| Missing | 43 (1.5) | 13 (0.9) | 18 (0.8) | 5 (0.4) | 18 (0.6) | 15 (1.0) | 16 (0.4) | 14 (0.8) | 18 (0.6) | 13 (0.9) | 2 (0.2) | 3 (0.6) |

| Sleep duration (h) | ||||||||||||

| < 7 | 871 (31.0) | 462 (32.9) | 685 (30.8) | 391 (35.2) | 907 (28.9) | 475 (30.2) | 957 (26.3) | 517 (28.4) | 705 (23.5) | 359 (23.9) | 249 (24.5) | 124 (24.4) |

| 7-9 | 1768 (63.0) | 845 (60.2) | 1436 (64.6) | 653 (58.7) | 2076 (66.1) | 1002 (63.8) | 2533 (69.5) | 1205 (66.2) | 2151 (71.7) | 1071 (71.4) | 727 (71.4) | 358 (70.3) |

| > 9 | 107 (3.8) | 72 (5.1) | 57 (2.6) | 52 (4.7) | 106 (3.4) | 70 (4.5) | 116 (3.2) | 80 (4.4) | 112 (3.7) | 56 (3.7) | 31 (3.0) | 18 (3.5) |

| Missing | 60 (2.1) | 24 (1.7) | 46 (2.1) | 16 (1.4) | 53 (1.7) | 24 (1.5) | 36 (1.0) | 19 (1.0) | 34 (1.1) | 15 (1.0) | 11 (1.1) | 9 (1.8) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.4 ± 6.8 | 31.5 ± 6.5 | 31.7 ± 6.6 | 31.9 ± 6.2 | 31.6 ± 6.4 | 31.8 ± 5.9 | 31.1 ± 5.7 | 31.2 ± 5.4 | 30.6 ± 5.4 | 30.8 ± 5.2 | 30.0 ± 4.8 | 30.2 ± 4.8 |

| Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.70 ± 1.02 | 4.63 ± 1.10 | 4.64 ± 0.98 | 4.60 ± 1.09 | 4.63 ± 0.96 | 4.57 ± 1.07 | 4.59 ± 0.97 | 4.52 ± 1.03 | 4.65 ± 0.96 | 4.60 ± 1.04 | 4.76 ± 1.01 | 4.66 ± 1.05 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.22 ± 0.32 | 1.21 ± 0.32 | 1.21 ± 0.30 | 1.21 ± 0.32 | 1.23 ± 0.31 | 1.23 ± 0.30 | 1.23 ± 0.31 | 1.22 ± 0.30 | 1.25 ± 0.31 | 1.25 ± 0.30 | 1.28 ± 0.31 | 1.26 ± 0.31 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.85 ± 0.73 | 2.83 ± 0.82 | 2.80 ± 0.71 | 2.79 ± 0.80 | 2.77 ± 0.70 | 2.76 ± 0.78 | 2.73 ± 0.69 | 2.72 ± 0.75 | 2.78 ± 0.70 | 2.77 ± 0.78 | 2.86 ± 0.73 | 2.80 ± 0.77 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 2.03 ± 1.43 | 2.02 ± 1.22 | 2.12 ± 1.47 | 2.10 ± 1.24 | 2.12 ± 1.43 | 2.09 ± 1.20 | 2.15 ± 1.38 | 2.16 ± 1.23 | 2.06 ± 1.27 | 2.08 ± 1.06 | 2.04 ± 1.20 | 2.07 ± 1.09 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 36.3 ± 5.4 | 54.3 ± 17.22 | 36.7 ± 5.8 | 52.6 ± 15.52 | 36.9 ± 5.5 | 51.4 ± 14.22 | 37.3 ± 5.3 | 49.7 ± 12.42 | 37.3 ± 6.7 | 47.6 ± 10.82 | 37.5 ± 4.5 | 46.5 ± 10.42 |

| Hypertension | 1501 (53.5) | 764 (54.5) | 1307 (58.8) | 671 (60.3) | 2079 (66.2) | 1012 (64.4) | 2414 (66.3) | 1179 (64.7) | 1963 (65.4) | 984 (65.6) | 643 (63.2) | 340 (66.8) |

| Heart disease | 301 (10.7) | 147 (10.5) | 306 (13.8) | 154 (13.8) | 450 (14.3) | 221 (14.1) | 607 (16.7) | 293 (16.1) | 556 (18.5) | 271 (18.1) | 183 (18.0) | 90 (17.7) |

| Depression | 300 (10.7) | 142 (10.1) | 167 (7.5) | 99 (8.9) | 230 (7.3) | 109 (6.9) | 284 (7.8) | 142 (7.8) | 160 (5.3) | 82 (5.5) | 42 (4.1) | 22 (4.3) |

For vision acuity analysis, 20067 participants (37.8% females) aged 40-70 years (mean ±S D: 59.9 ± 7.9), were included. Diabetic participants across all age groups of diabetes diagnosis had higher HbA1c than the controls (Table 2). Individuals with T1D were more likely to have a normal sleep duration and higher HbA1c compared to the controls (Supplementary Table 3).

| < 45 yr | 45-49 yr | 50-54 yr | 55-59 yr | 60-64 yr | ≥ 65 yr | |||||||

| Non-diabetes | Diabetes | Non-diabetes | Diabetes | Non-diabetes | Diabetes | Non-diabetes | Diabetes | Non-diabetes | Diabetes | Non-diabetes | Diabetes | |

| Age (yr) | 53.1 ± 8.6 | 52.8 ± 8.5 | 54.8 ± 8.5 | 54.7 ± 5.8 | 59.0 ± 7.9 | 58.9 ± 4.8 | 62.5 ± 5.9 | 62.3 ± 3.5 | 65.2 ± 3.6 | 65.0 ± 2.4 | 67.5 ± 2.8 | 67.6 ± 1.3 |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Female | 751 (37.6) | 379 (37.9) | 577 (36.4) | 284 (35.8) | 937 (39.2) | 480 (40.2) | 1035 (35.5) | 512 (35.1) | 962 (36.7) | 485 (37.1) | 363 (41.4) | 177 (40.4) |

| Male | 1249 (62.5) | 621 (62.1) | 1009 (63.6) | 509 (64.2) | 1453 (60.8) | 715 (59.8) | 1879 (64.5) | 945 (64.9) | 1656 (63.3) | 824 (62.9) | 513 (58.6) | 261 (59.6) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Whites | 1268 (63.4) | 606 (60.6) | 1078 (68.0) | 518 (65.3) | 1793 (75.0) | 866 (72.5) | 2478 (85.0) | 1223 (83.9) | 2302 (87.9) | 1122 (85.7) | 768 (87.7) | 379 (86.5) |

| Non-whites | 611 (30.6) | 373 (37.3) | 454 (28.6) | 270 (34.0) | 511 (21.4) | 306 (25.6) | 378 (13.0) | 222 (15.2) | 267 (10.2) | 172 (13.1) | 86 (9.8) | 54 (12.3) |

| Unknown | 121 (6.1) | 21 (2.1) | 54 (3.4) | 5 (0.6) | 86 (3.6) | 23 (1.9) | 58 (2.0) | 12 (0.8) | 49 (1.9) | 15 (1.1) | 22 (2.5) | 5 (1.1) |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| 0-5 yr | 585 (29.3) | 285 (28.5) | 490 (30.9) | 215 (27.1) | 683 (28.6) | 330 (27.6) | 755 (25.9) | 359 (24.6) | 619 (23.6) | 306 (23.4) | 193 (22.0) | 92 (21.0) |

| 6-12 yr | 942 (47.1) | 487 (48.7) | 811 (51.1) | 430 (54.2) | 1171 (49.0) | 589 (49.3) | 1359 (46.6) | 693 (47.6) | 1156 (44.2) | 590 (45.1) | 375 (42.8) | 183 (41.8) |

| ≥ 13 yr | 369 (18.5) | 192 (19.2) | 239 (15.1) | 130 (16.4) | 462 (19.3) | 244 (20.4) | 736 (25.3) | 370 (25.4) | 783 (29.9) | 385 (29.4) | 287 (32.8) | 151 (34.5) |

| Missing | 104 (5.2) | 36 (3.6) | 46 (2.9) | 18 (2.3) | 74 (3.1) | 32 (2.7) | 64 (2.2) | 35 (2.4) | 60 (2.3) | 28 (2.1) | 21 (2.4) | 12 (2.7) |

| Household income (pounds) | ||||||||||||

| < 18000 | 475 (23.8) | 266 (26.6) | 359 (22.6) | 217 (27.4) | 607 (25.4) | 330 (27.6) | 842 (28.9) | 418 (28.7) | 796 (30.4) | 414 (31.6) | 286 (32.6) | 165 (37.7) |

| 18000-30999 | 377 (18.9) | 212 (21.2) | 346 (21.8) | 167 (21.1) | 521 (21.8) | 244 (20.4) | 718 (24.6) | 370 (25.4) | 673 (25.7) | 341 (26.1) | 227 (25.9) | 106 (24.2) |

| 31000-51999 | 372 (18.6) | 179 (17.9) | 313 (19.7) | 143 (18.0) | 415 (17.4) | 205 (17.2) | 493 (16.9) | 245 (16.8) | 402 (15.4) | 199 (15.2) | 120 (13.7) | 55 (12.6) |

| 52000-100000 | 256 (12.8) | 113 (11.3) | 234 (14.8) | 106 (13.4) | 298 (12.5) | 151 (12.6) | 301 (10.3) | 149 (10.2) | 220 (8.4) | 106 (8.1) | 52 (5.9) | 23 (5.3) |

| > 100000 | 72 (3.6) | 34 (3.4) | 61 (3.8) | 24 (3.0) | 77 (3.2) | 29 (2.4) | 82 (2.8) | 36 (2.5) | 54 (2.1) | 15 (1.1) | 14 (1.6) | 5 (1.1) |

| Unknown | 132 (6.6) | 76 (7.6) | 70 (4.4) | 56 (7.1) | 122 (5.1) | 83 (6.9) | 117 (4.0) | 71 (4.9) | 126 (4.8) | 71 (5.4) | 44 (5.0) | 24 (5.5) |

| Not answered | 316 (15.8) | 120 (12.0) | 203 (12.8) | 80 (10.1) | 350 (14.6) | 153 (12.8) | 361 (12.4) | 168 (11.5) | 347 (13.3) | 163 (12.5) | 133 (15.2) | 60 (13.7) |

| Physical activity (MET-minutes/week) | 2225 ± 2087 | 2269 ± 2134 | 2154 ± 2019 | 2147 ± 2086 | 2206 ± 2023 | 2180 ± 2171 | 2433 ± 2190 | 2384 ± 2204 | 2410 ± 2206 | 2426 ± 2231 | 2591 ± 2341 | 2518 ± 2271 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||||||||

| Never | 233 (11.7) | 156 (15.6) | 178 (11.2) | 106 (13.4) | 205 (8.6) | 135 (11.3) | 213 (7.3) | 107 (7.3) | 168 (6.4) | 91 (7.0) | 60 (6.8) | 30 (6.8) |

| Previous | 110 (5.5) | 78 (7.8) | 96 (6.1) | 58 (7.3) | 138 (5.8) | 85 (7.1) | 170 (5.8) | 81 (5.6) | 131 (5.0) | 77 (5.9) | 55 (6.3) | 34 (7.8) |

| Current | 1595 (79.8) | 755 (75.5) | 1283 (80.9) | 623 (78.6) | 2000 (83.7) | 966 (80.8) | 2509 (86.1) | 1260 (86.5) | 2294 (87.6) | 1133 (86.6) | 751 (85.7) | 371 (84.7) |

| Missing | 62 (3.1) | 11 (1.1) | 29 (1.8) | 6 (0.8) | 47 (2.0) | 9 (0.8) | 22 (0.8) | 9 (0.6) | 25 (1.0) | 8 (0.6) | 10 (1.1) | 3 (0.7) |

| Smoking | ||||||||||||

| Never | 1089 (54.5) | 591 (59.1) | 778 (49.1) | 405 (51.1) | 1132 (47.4) | 590 (49.4) | 1271 (43.6) | 648 (44.5) | 1144 (43.7) | 550 (42.0) | 383 (43.7) | 182 (41.6) |

| Former | 581 (29.1) | 260 (26.0) | 563 (35.5) | 258 (32.5) | 946 (39.6) | 458 (38.3) | 1308 (44.9) | 648 (44.5) | 1220 (46.6) | 632 (48.3) | 410 (46.8) | 222 (50.7) |

| Current | 260 (13.0) | 130 (13.0) | 222 (14.0) | 124 (15.6) | 273 (11.4) | 130 (10.9) | 312 (10.7) | 145 (10.0) | 221 (8.4) | 109 (8.3) | 70 (8.0) | 31 (7.1) |

| Missing | 70 (3.5) | 19 (1.9) | 23 (1.5) | 6 (0.8) | 39 (1.6) | 17 (1.4) | 23 (0.8) | 16 (1.1) | 33 (1.3) | 18 (1.4) | 13 (1.5) | 3 (0.7) |

| Sleep duration (h) | ||||||||||||

| < 7 | 580 (29.0) | 313 (31.3) | 474 (29.9) | 281 (35.4) | 652 (27.3) | 347 (29.0) | 745 (25.6) | 392 (26.9) | 594 (22.7) | 314 (24.0) | 231 (26.4) | 98 (22.4) |

| 7-9 | 1274 (63.7) | 625 (62.5) | 1025 (64.6) | 461 (58.1) | 1604 (67.1) | 782 (65.4) | 2043 (70.1) | 982 (67.4) | 1880 (71.8) | 923 (70.5) | 610 (69.6) | 320 (73.1) |

| > 9 | 64 (3.2) | 39 (3.9) | 48 (3.0) | 37 (4.7) | 72 (3.0) | 42 (3.5) | 90 (3.1) | 63 (4.3) | 102 (3.9) | 55 (4.2) | 23 (2.6) | 11 (2.5) |

| Missing | 82 (4.1) | 23 (2.3) | 39 (2.5) | 14 (1.8) | 62 (2.6) | 24 (2.0) | 36 (1.2) | 20 (1.4) | 42 (1.6) | 17 (1.3) | 12 (1.4) | 9 (2.1) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.3 ± 6.7 | 31.2 ± 6.7 | 31.8 ± 6.6 | 32.0 ± 6.3 | 31.0 ± 6.1 | 31.3 ± 5.6 | 30.8 ± 5.5 | 30.9 ± 5.1 | 30.6 ± 5.5 | 30.6 ± 5.1 | 29.8 ± 4.9 | 30.1 ± 4.9 |

| Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.67 ± 1.01 | 4.62 ± 1.11 | 4.63 ± 1.00 | 4.59 ± 1.08 | 4.59 ± 0.95 | 4.58 ± 1.06 | 4.58 ± 0.95 | 4.52 ± 1.05 | 4.68 ± 0.95 | 4.61 ± 1.04 | 4.71 ± 0.96 | 4.68 ± 1.06 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.24 ± 0.31 | 1.23 ± 0.33 | 1.21 ± 0.31 | 1.22 ± 0.33 | 1.24 ± 0.30 | 1.24 ± 0.31 | 1.24 ± 0.31 | 1.24 ± 0.30 | 1.27 ± 0.30 | 1.26 ± 0.31 | 1.29 ± 0.32 | 1.27 ± 0.31 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.83 ± 0.75 | 2.81 ± 0.83 | 2.79 ± 0.72 | 2.78 ± 0.78 | 2.75 ± 0.68 | 2.76 ± 0.78 | 2.72 ± 0.68 | 2.70 ± 0.76 | 2.80 ± 0.69 | 2.76 ± 0.77 | 2.83 ± 0.71 | 2.82 ± 0.78 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.88 ± 1.28 | 1.92 ± 1.15 | 2.08 ± 1.47 | 2.07 ± 1.22 | 2.01 ± 1.37 | 2.00 ± 1.10 | 2.11 ± 1.41 | 2.10 ± 1.21 | 2.01 ± 1.21 | 2.02 ± 1.04 | 1.96 ± 1.19 | 1.98 ± 1.01 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 36.6 ± 5.3 | 53.5 ± 16.62 | 36.6 ± 5.0 | 52.8 ± 15.62 | 37.0 ± 4.9 | 51.2 ± 13.82 | 37.1 ± 5.3 | 49.4 ± 12.52 | 37.3 ± 7.0 | 47.4 ± 10.92 | 37.6 ± 10.3 | 45.5 ± 9.62 |

| Hypertension | 1058 (52.9) | 528 (52.8) | 971 (61.2) | 480 (60.5) | 1486 (62.2) | 746 (62.4) | 1883 (64.6) | 930 (63.8) | 1707 (65.2) | 842 (64.3) | 547 (62.4) | 280 (63.9) |

| Heart disease | 200 (10.0) | 99 (9.9) | 177 (11.2) | 95 (12.0) | 314 (13.1) | 157 (13.1) | 481 (16.5) | 230 (15.8) | 447 (17.1) | 222 (17.0) | 158 (18.0) | 78 (17.8) |

| Depression | 162 (8.1) | 84 (8.4) | 129 (8.1) | 66 (8.3) | 146 (6.1) | 70 (5.9) | 190 (6.5) | 95 (6.5) | 127 (4.9) | 63 (4.8) | 24 (2.7) | 12 (2.7) |

Over a median follow-up of 11.0 years (interquartile range: 10.7-11.5), 3874 new cases of cataract, 665 new cases of gla

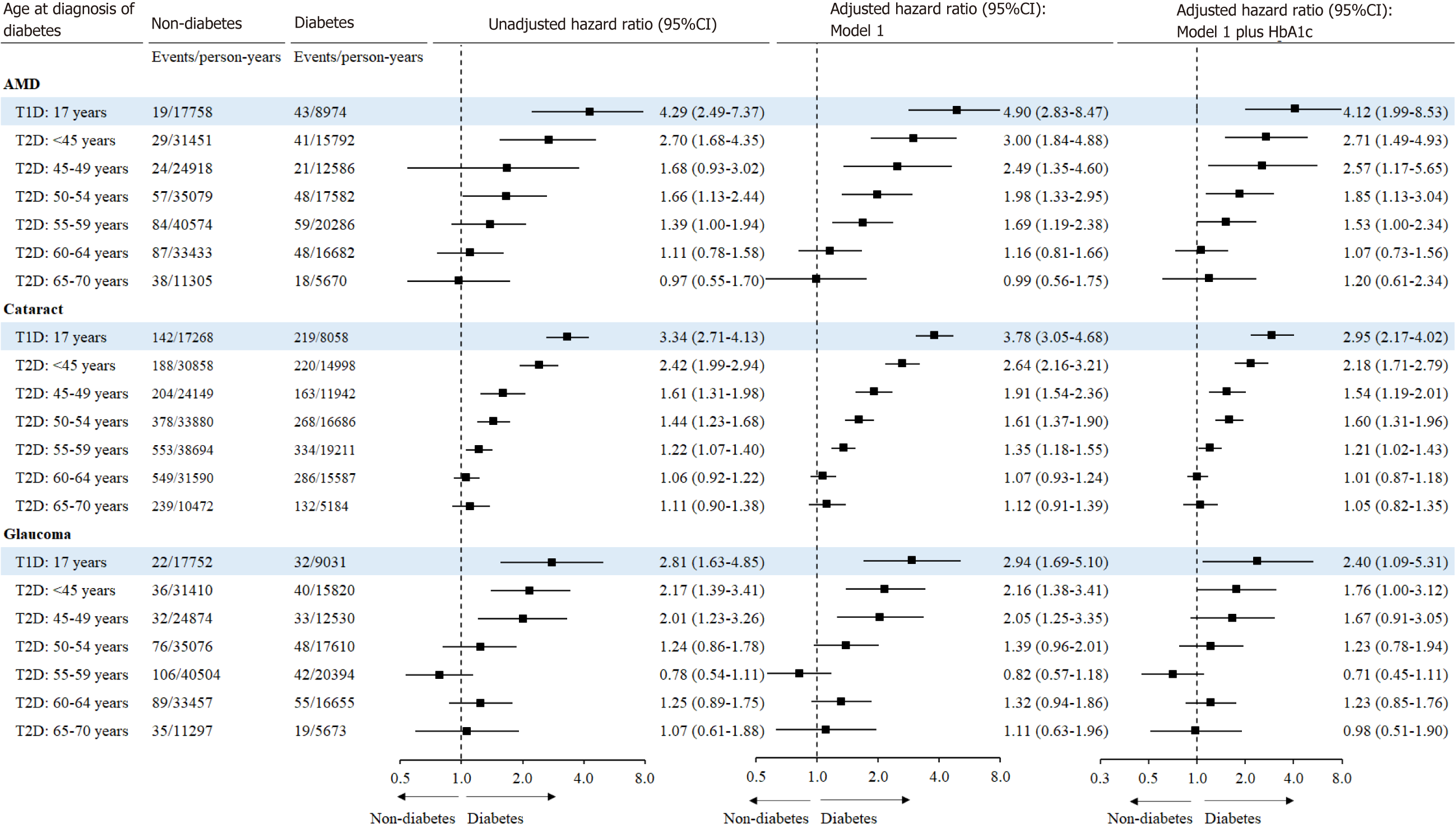

As shown in Figure 2, the relative risk for incident AMD associated with diabetes decreased with the increasing age at diagnosis of diabetes. In the multivariable-adjusted analysis, T2D diagnosed at age of < 45 [HR (95%CI): 2.71 (1.49-4.93)], 45-49 [2.57 (1.17-5.65)], 50-54 [1.85 (1.13-3.04)], or 55-59 years [1.53 (1.00-2.34)] was associated with a higher risk of incident AMD. T1D [HR (95%CI): 4.12 (1.99-8.53)] was associated with an increased risk of AMD independent of concurrent HbA1c.

Similarly, the association between diabetes and glaucoma was dependent on the age at diagnosis of diabetes. After adjustment for HbA1c and other covariates, only diabetes diagnosed at age of < 45 years only [HR (95%CI): 1.76 (1.00-3.12)] was associated with an increased risk of glaucoma. The multivariable-adjusted HR (95%CI) for glaucoma associated with T1D was 2.40 (1.09-5.31).

In the multivariable-adjusted model, the HRs (95%CIs) for incident cataract associated with diabetes diagnosed at < 45, 45-49, 50-54, and 55-59 years of age were 2.18 (1.71-2.79), 1.54 (1.19-2.01), 1.60 (1.31-1.96), and 1.21 (1.02-1.43), respectively. T1D was independently associated with an increased risk of incident cataract [2.95 (2.17-4.02)].

As shown in Supplementary Figure 2, T2D diagnosed at < 45, 45-49, 50-54, and 55-59, but not 60-64 or ≥ 65 years of age was associated with an increased risk of cataract surgery, where individuals with T2D diagnosed < 45 years had the highest excess risk of cataract surgery [HR (95%CI): 2.67 (1.88-3.79)]. The multivariable-adjusted HR (95%CI) for cataract surgery associated with T1D was 4.63 (3.10-6.93).

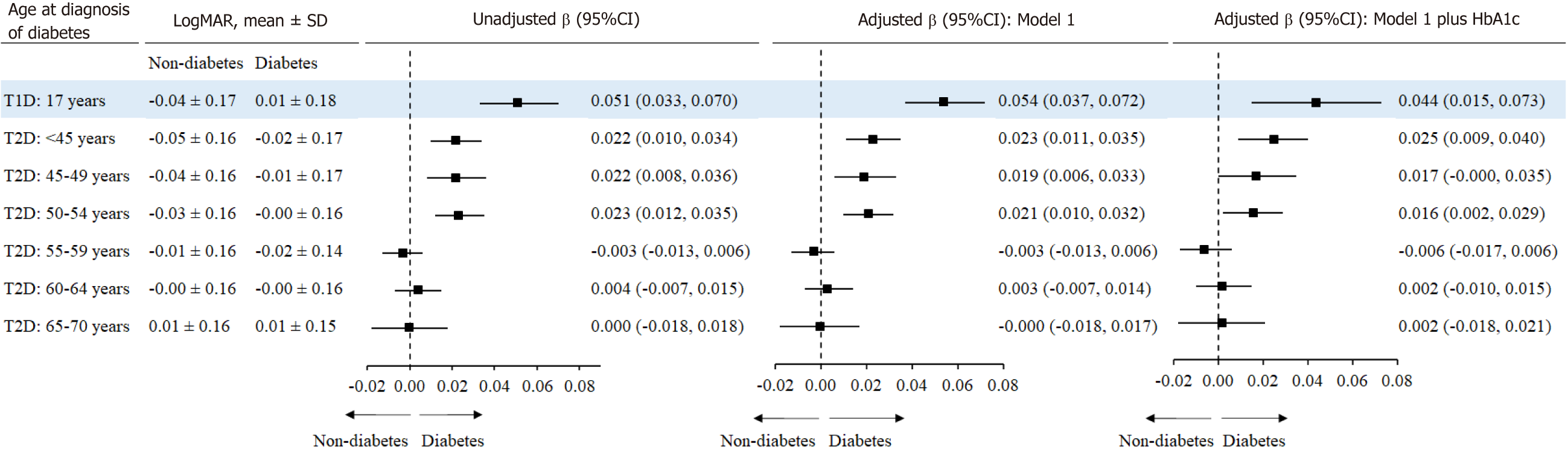

After adjustment for covariates and HbA1c, individuals with T2D diagnosed at age of < 45 [β 95%CI: 0.025 (0.009, 0.040)], and 50-54 years [0.016 (0.002, 0.029)] had higher LogMAR compared to the corresponding controls. T1D was associated with a larger LogMAR [0.044 (0.015,0.073), Figure 3].

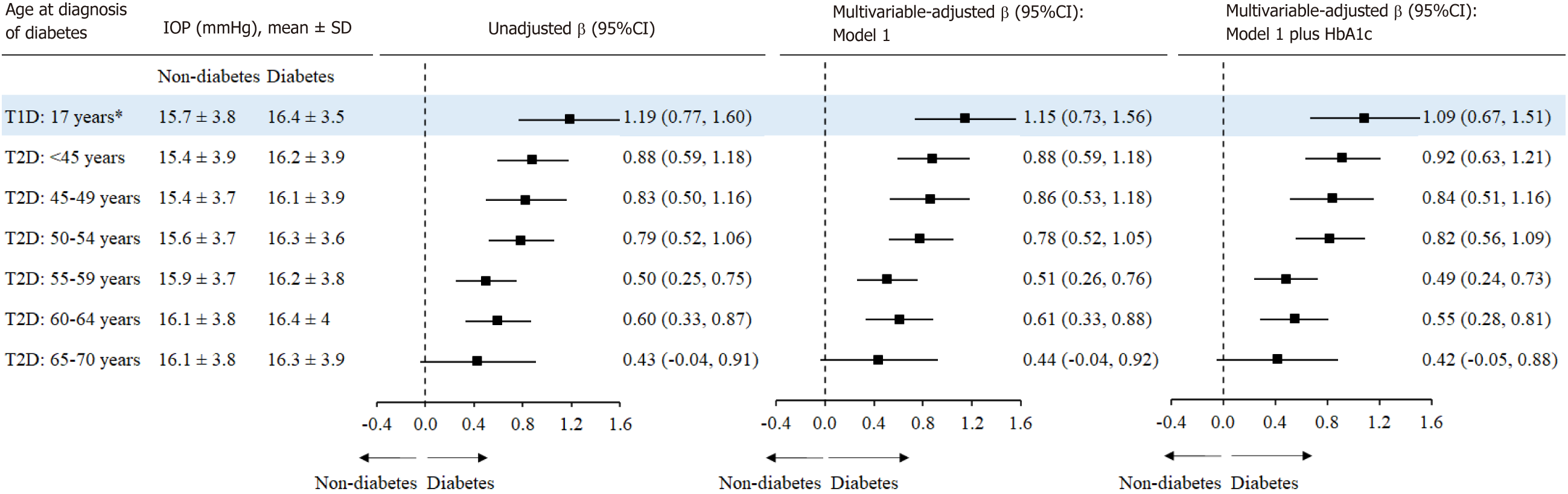

As shown in Figure 4, individuals with T2D diagnosed at < 45 [β (95%CI): 0.88 (0.59, 1.18) mmHg], 45-49 [0.86 (0.53, 1.18) mmHg], and 50-54 years of age [0.78 (0.52, 1.05) mmHg] had higher IOP compared with the controls. The β (95%CI) for IOP associated with T1D was larger [1.15 (0.73,1.56) mmHg].

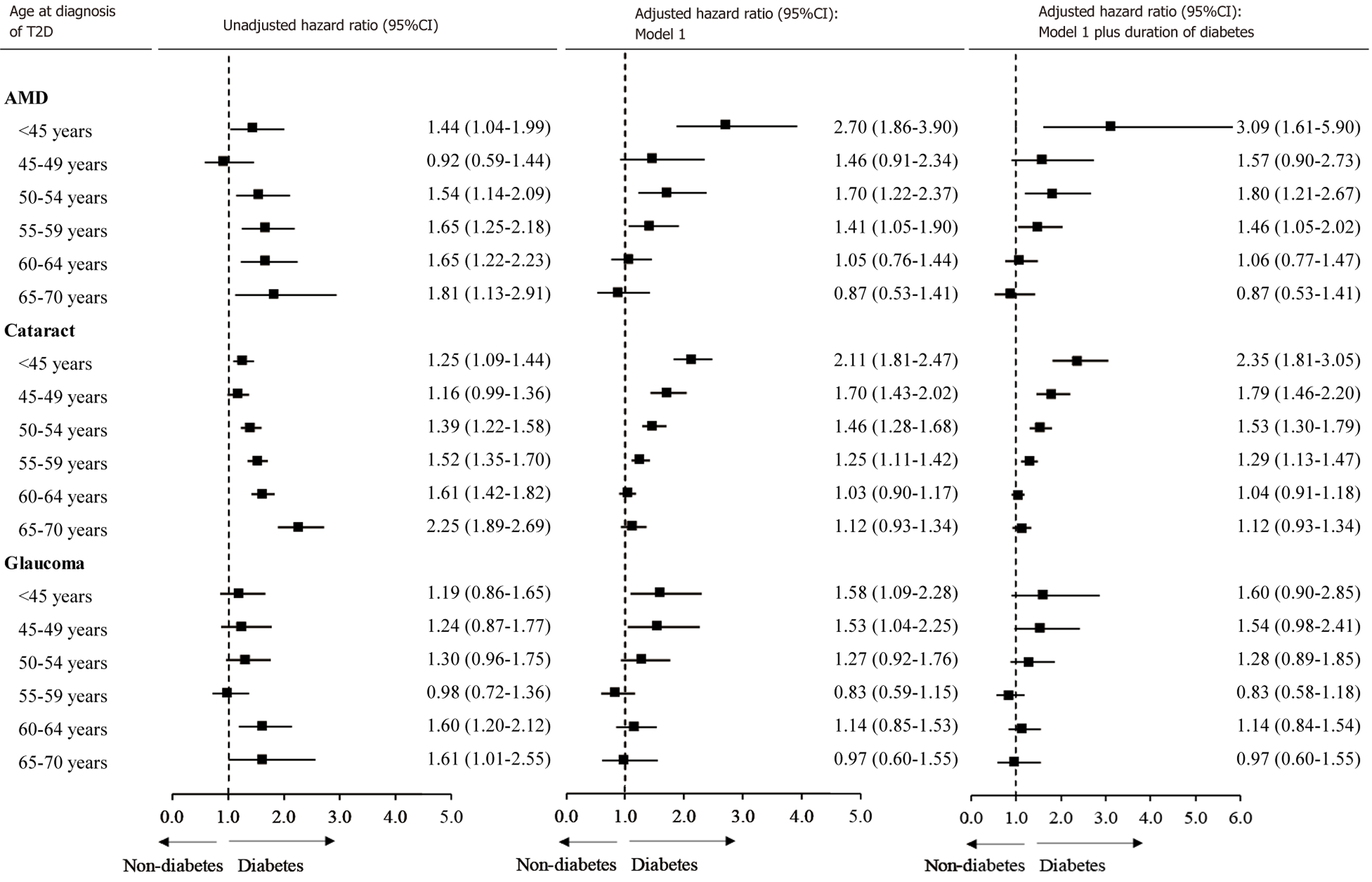

Individuals with diabetes diagnosed at < 50 years of age were younger but had a higher incidence of ocular diseases compared with controls (Supplementary Figure 3). A larger HR was observed for those with diabetes diagnosed at older age. After adjustment for covariates, the association was reversed with diabetes diagnosed at younger age associated with a larger HR. This trend remained consistent after further adjustment for diabetes duration (Figure 5). Individuals with diabetes diagnosed at < 45, 45-49, or 50-54 years of age were younger and had higher LogMAR compared with controls (Supplementary Figure 4). Older age at the diagnosis of diabetes was associated with a larger increase in LogMAR compared with controls. However, after adjustment for covariates, diabetes diagnosed at a younger age was associated with a larger increase in LogMAR (Supplementary Figure 5).

This large prospective cohort study demonstrated that younger age at diagnosis of diabetes was associated with a larger relative risk for cataract, glaucoma, and AMD independent of concurrent HbA1c levels. Individuals with T2D diagnosed before the age of 45 years were more than twice as likely to develop these ocular conditions, while those with T1D exhibited a more pronounced relative risk. Similarly, T2D diagnosed before the age of 55 years and T1D were associated with an increased LogMAR. Sensitivity analysis suggests these associations are independent of duration of diabetes.

Diabetes is one of the most important determinants for cataract[8,28,29]. We found that diabetes was associated with an increased risk of incident cataract, and in particular diabetes diagnosed at < 45 years of age had larger excessive risk of cataract. To our knowledge, no previous study has investigated the impact of age at diagnosis of diabetes on the association between diabetes and cataract. However, several studies have shown that the association between diabetes and cataract was stronger among younger than older adults[28-30]. In a cross-sectional analysis, longer duration of diabetes was associated with a higher prevalence of cataract[28]. These studies provide indirect evidence for the rationale of our findings that younger age at diagnosis of diabetes was associated with a larger excess risk of cataract.

Previous studies have been inconsistent on the association between diabetes and glaucoma. Although a meta-analysis showed that diabetes was associated with a higher risk of glaucoma [relative risk (95%CI): 1.36 (1.25-1.50)], only three out of seven prospective studies included in the meta-analysis found a significant association between diabetes and glaucoma[11]. The lack of significance in some studies may be attributed to a relatively short duration of diabetes[31]. We found individuals with T1D or T2D diagnosed before the age of 45 years but not at 45 years or older had a higher risk of glaucoma. This is consistent with previous studies showing controversial associations between diabetes and glaucoma. It is possible that cumulative exposure to hyperglycemia from an early life may contribute to increased IOP[32], thus elevating the risk of glaucoma. This is supportive by further analysis demonstrating that diabetes diagnosed at a younger age was associated with a larger increase in IOP.

A meta-analysis showed that diabetes was associated with an increased risk of incident AMD [relative risk (95%CI): 1.05 (1.00–1.11)], although the effect size is small[19]. Among 7 cohort studies in this meta-analysis, only one study reported a significant association[33]. Another prospective study (not included in this meta-analysis) of 71904 patients with diabetes and 270213 patients without diabetes found no significant association between diabetes and incident AMD[34]. A recent prospective study even found that diabetes was associated with a decreased progression of AMD[35]. However, we found that diabetes diagnosed at a younger age but not at an older age was associated with an increased risk of AMD. This finding may offer an explanation for the lack of significant associations reported in most previous studies. Notably, previous studies often combined individuals with diabetes diagnosed at both younger and older ages, which may introduce a bias towards a null association.

Whether the association between diabetes and incident cataract, glaucoma, or AMD is moderated by the age at diagnosis of diabetes has not been reported in previous studies. However, our study is consistent with a cross-sectional study of 3322 individuals demonstrating that early-onset T2D was associated with a higher prevalence of diabetic re

The mechanisms undelying the association between a younger age at the diagnosis of diabetes and ocular conditions and vision loss remain largely unknown. A prospective study has shown that T2D developed at a younger age was associated with a higher risk of obesity, worse lipid profiles and higher HbA1c, and a faster deterioration in glycaemic control compared to those with diabetes onset at an older age[37]. These markers have been shown to be important determinants for cataract[38] and glaucoma[31,39] among diabetic patients. This may indicate that early-onset diabetes may represent a more pathogenic condition than late-onset disease for the development of ocular conditions[37]. Fur

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first prospective cohort study to examine the association of age at the dia

In conclusion, our findings suggest the age at the diagnosis of diabetes plays an important role in the association between diabetes and incident cataract, glaucoma, and AMD as well as vision. A younger age at the diagnosis of diabetes was associated with larger excessive relative risk for ocular conditions and larger vision loss. T1D appears to have potentially more harmful effects.

Diabetes has been linked to numerous ocular conditions, including cataract, glaucomaand age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Several studies have demonstrated a positive relationship between diabetes and AMD, but more studies did not find a significant association. Diabetes may have different associations with different stages of ocular conditions, and the duration of diabetes may affect the development of diabetic eye disease. It is important to identify the life stage at which a diagnosis of diabetes is associated with the highest risk of najor ocular conditions for the prevention or screening of these conditions.

To examine associations between the age of diabetes diagnosis and the incidence of cataract, glaucoma, AMD, and vision acuity. It is important to identify the life stage at which a diagnosis of diabetes is associated with the highest risk of najor ocular conditions for the prevention or screening of these conditions.

To examine associations between the age of diabetes diagnosis and the incidence of cataract, glaucoma, AMD, and vision acuity. A stronger association between diabetes and incident ocular conditions was observed where diabetes was dia

This is the first prospective cohort study to examine the association of age at the diagnosis of diabetes with main ocular conditions. Our analysis was using the UK Biobank. The cohort included 8709 diabetic participants and 17418 controls for ocular condition analysis, and 6689 diabetic participants and 13378 controls for vision analysis. Ocular diseases were identified using inpatient records until January 2021. Vision acuity was assessed using a chart.

This large prospective cohort study demonstrated that younger age at diagnosis of diabetes was associated with a larger relative risk for cataract, glaucoma, and AMD independent of concurrent glycated haemoglobin levels. Individuals with type 2 diabetes (T2D) diagnosed before the age of 45 years were more than twice as likely to develop these ocular conditions, while those with type 1 diabetes (T1D) exhibited a more pronounced relative risk. Similarly, T2D diagnosed before the age of 55 years and T1D were associated with an increased LogMAR. However, the clear pathogenesis of ocular conditions, especially AMD due to diabetes, needs further exploration in research.

Our findings suggest the age at the diagnosis of diabetes plays an important role in the association between diabetes and incident cataract, glaucoma, and AMD as well as vision. A younger age at the diagnosis of diabetes was associated with larger excessive relative risk for ocular conditions and larger vision loss. T1D appears to have potentially more harmful effects.

Investigated the impact of age at diagnosis of diabetes on the association between diabetes and cataract, glaucoma, AMD, and vision acuity, by the more detailed breakdown of factors. To analyse more about the shared genetics between diabetes and ocular conditions.

This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under Application Number (62443, 62525, 62491, 94372, 105658). We thank the participants of the UK Biobank. We thank the language proofreading by Shahin Alam.

| 1. | GBD 2019 Blindness and Vision Impairment Collaborators; Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: the Right to Sight: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9:e144-e160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1680] [Cited by in RCA: 1809] [Article Influence: 361.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Keel S, Cieza A. Rising to the challenge: estimates of the magnitude and causes of vision impairment and blindness. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9:e100-e101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pearce I, Simó R, Lövestam-Adrian M, Wong DT, Evans M. Association between diabetic eye disease and other complications of diabetes: Implications for care. A systematic review. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:467-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Araújo LR, Orefice JL, Gonçalves MA, Guimarães NS, Soares AN, Salomon T, de Souza AH. Use of digital retinography to detect vascular changes in pre-diabetic patients: a cross-sectional study. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2023;15:225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kiziltoprak H, Tekin K, Inanc M, Goker YS. Cataract in diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes. 2019;10:140-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 6. | Fujita A, Hashimoto Y, Matsui H, Yasunaga H, Aihara M. Association between lifestyle habits and glaucoma incidence: a retrospective cohort study. Eye (Lond). 2023;37:3470-3476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Heesterbeek TJ, Lorés-Motta L, Hoyng CB, Lechanteur YTE, den Hollander AI. Risk factors for progression of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2020;40:140-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 46.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Floud S, Kuper H, Reeves GK, Beral V, Green J. Risk Factors for Cataracts Treated Surgically in Postmenopausal Women. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:1704-1710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chan TCW, Bala C, Siu A, Wan F, White A. Risk Factors for Rapid Glaucoma Disease Progression. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;180:151-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jiang X, Varma R, Wu S, Torres M, Azen SP, Francis BA, Chopra V, Nguyen BB; Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Group. Baseline risk factors that predict the development of open-angle glaucoma in a population: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2245-2253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhao YX, Chen XW. Diabetes and risk of glaucoma: systematic review and a Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int J Ophthalmol. 2017;10:1430-1435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Clemons TE, Milton RC, Klein R, Seddon JM, Ferris FL 3rd; Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. Risk factors for the incidence of Advanced Age-Related Macular Degeneration in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) AREDS report no. 19. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:533-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 404] [Cited by in RCA: 485] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang IK, Lin HJ, Wan L, Lin CL, Yen TH, Sung FC. Risk of age-related macular degeneration in end-stage renal disease patients receiving long-term dialysis. Retina. 2016;36:1866-1873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tomany SC, Wang JJ, Van Leeuwen R, Klein R, Mitchell P, Vingerling JR, Klein BE, Smith W, De Jong PT. Risk factors for incident age-related macular degeneration: pooled findings from 3 continents. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1280-1287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 390] [Cited by in RCA: 413] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jonasson F, Fisher DE, Eiriksdottir G, Sigurdsson S, Klein R, Launer LJ, Harris T, Gudnason V, Cotch MF. Five-year incidence, progression, and risk factors for age-related macular degeneration: the age, gene/environment susceptibility study. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:1766-1772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Saunier V, Merle BMJ, Delyfer MN, Cougnard-Grégoire A, Rougier MB, Amouyel P, Lambert JC, Dartigues JF, Korobelnik JF, Delcourt C. Incidence of and Risk Factors Associated With Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Four-Year Follow-up From the ALIENOR Study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136:473-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Buch H, Vinding T, la Cour M, Jensen GB, Prause JU, Nielsen NV. Risk factors for age-related maculopathy in a 14-year follow-up study: the Copenhagen City Eye Study. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2005;83:409-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tan JS, Mitchell P, Smith W, Wang JJ. Cardiovascular risk factors and the long-term incidence of age-related macular degeneration: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1143-1150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chen X, Rong SS, Xu Q, Tang FY, Liu Y, Gu H, Tam PO, Chen LJ, Brelén ME, Pang CP, Zhao C. Diabetes mellitus and risk of age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sattar N, Rawshani A, Franzén S, Svensson AM, Rosengren A, McGuire DK, Eliasson B, Gudbjörnsdottir S. Age at Diagnosis of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Associations With Cardiovascular and Mortality Risks. Circulation. 2019;139:2228-2237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 377] [Article Influence: 62.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Ramsey DJ, Kwan JT, Sharma A. Keeping an eye on the diabetic foot: The connection between diabetic eye disease and wound healing in the lower extremity. World J Diabetes. 2022;13:1035-1048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 22. | Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, Beral V, Burton P, Danesh J, Downey P, Elliott P, Green J, Landray M, Liu B, Matthews P, Ong G, Pell J, Silman A, Young A, Sprosen T, Peakman T, Collins R. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6354] [Cited by in RCA: 8733] [Article Influence: 793.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Eastwood SV, Mathur R, Atkinson M, Brophy S, Sudlow C, Flaig R, de Lusignan S, Allen N, Chaturvedi N. Algorithms for the Capture and Adjudication of Prevalent and Incident Diabetes in UK Biobank. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0162388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 365] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chua SYL, Luben RN, Hayat S, Broadway DC, Khaw KT, Warwick A, Britten A, Day AC, Strouthidis N, Patel PJ, Khaw PT, Foster PJ, Khawaja AP; UK Biobank Eye and Vision Consortium. Alcohol Consumption and Incident Cataract Surgery in Two Large UK Cohorts. Ophthalmology. 2021;128:837-847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chua SYL, Thomas D, Allen N, Lotery A, Desai P, Patel P, Muthy Z, Sudlow C, Peto T, Khaw PT, Foster PJ; UK Biobank Eye & Vision Consortium. Cohort profile: design and methods in the eye and vision consortium of UK Biobank. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e025077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | International Physical Activity Questionnaire. Guidelines for data processing and analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). Nov 2005 [cited 3 August 2022]. Available from: https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/showcase/ukb/docs/ipaq_analysis.pdf. |

| 27. | Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Cappuccio FP, Brunner E, Miller MA, Kumari M, Marmot MG. A prospective study of change in sleep duration: associations with mortality in the Whitehall II cohort. Sleep. 2007;30:1659-1666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 405] [Cited by in RCA: 396] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Klein BE, Klein R, Moss SE. Prevalence of cataracts in a population-based study of persons with diabetes mellitus. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:1191-1196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 29. | Klein BE, Klein R, Moss SE. Incidence of cataract surgery in the Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;119:295-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Nielsen NV, Vinding T. The prevalence of cataract in insulin-dependent and non-insulin-dependent-diabetes mellitus. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1984;62:595-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Zhao D, Cho J, Kim MH, Friedman DS, Guallar E. Diabetes, fasting glucose, and the risk of glaucoma: a meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:72-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Weinreb RN, Aung T, Medeiros FA. The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: a review. JAMA. 2014;311:1901-1911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1848] [Cited by in RCA: 3003] [Article Influence: 250.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Shalev V, Sror M, Goldshtein I, Kokia E, Chodick G. Statin use and the risk of age related macular degeneration in a large health organization in Israel. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2011;18:83-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | He MS, Chang FL, Lin HZ, Wu JL, Hsieh TC, Lee YC. The Association Between Diabetes and Age-Related Macular Degeneration Among the Elderly in Taiwan. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:2202-2211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Chakravarthy U, Bailey CC, Scanlon PH, McKibbin M, Khan RS, Mahmood S, Downey L, Dhingra N, Brand C, Brittain CJ, Willis JR, Venerus A, Muthutantri A, Cantrell RA. Progression from Early/Intermediate to Advanced Forms of Age-Related Macular Degeneration in a Large UK Cohort: Rates and Risk Factors. Ophthalmol Retina. 2020;4:662-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Middleton TL, Constantino MI, Molyneaux L, D'Souza M, Twigg SM, Wu T, Yue DK, Zoungas S, Wong J. Young-onset type 2 diabetes and younger current age: increased susceptibility to retinopathy in contrast to other complications. Diabet Med. 2020;37:991-999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Steinarsson AO, Rawshani A, Gudbjörnsdottir S, Franzén S, Svensson AM, Sattar N. Short-term progression of cardiometabolic risk factors in relation to age at type 2 diabetes diagnosis: a longitudinal observational study of 100,606 individuals from the Swedish National Diabetes Register. Diabetologia. 2018;61:599-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Drinkwater JJ, Davis WA, Davis TME. A systematic review of risk factors for cataract in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2019;35:e3073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Song BJ, Aiello LP, Pasquale LR. Presence and Risk Factors for Glaucoma in Patients with Diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2016;16:124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Cha AE, Villarroel MA, Vahratian A. Eye Disorders and Vision Loss Among U.S. Adults Aged 45 and Over With Diagnosed Diabetes, 2016-2017. NCHS Data Brief. 2019;1-8. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Shen L, Walter S, Melles RB, Glymour MM, Jorgenson E. Diabetes Pathology and Risk of Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma: Evaluating Causal Mechanisms by Using Genetic Information. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183:147-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Chang C, Zhang K, Veluchamy A, Hébert HL, Looker HC, Colhoun HM, Palmer CN, Meng W. A Genome-Wide Association Study Provides New Evidence That CACNA1C Gene is Associated With Diabetic Cataract. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:2246-2250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Ludwig PE, Freeman SC, Janot AC. Novel stem cell and gene therapy in diabetic retinopathy, age related macular degeneration, and retinitis pigmentosa. Int J Retina Vitreous. 2019;5:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Endocrinology and metabolism

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Al-Suhaimi EA, Saudi Arabia; Cai L, United States S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang YL