Published online Nov 15, 2024. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v15.i11.2220

Revised: August 17, 2024

Accepted: September 23, 2024

Published online: November 15, 2024

Processing time: 197 Days and 3.8 Hours

Diabetic nephropathy (DN), affecting half of diabetic patients and contributing significantly to end-stage kidney disease, poses a substantial medical challenge requiring dialysis or transplantation. The nuanced onset and clinical progression of kidney disease in diabetes involve consistent renal function decline and persistent albuminuria.

To investigate Tiliroside's (Til) protective effect against diabetic nephropathy (DN) in rats under diabetic conditions.

Five groups of six rats each were included in this study: Rats treated with DMSO by intraperitoneal injection as controls, those treated with STZ by intraperitoneal injection, those treated with STZ + Til (25 mg/kg body weight [bwt]) or Til (50 mg/kg bwt), and those treated with anti-diabetic medication glibenclamide (600 μg/kg bwt). Biochemical markers, fasting blood glucose, food intake, kidney weight, antioxidant enzymes, inflammatory and fibrotic markers, and renal injury were monitored in different groups. Molecular docking analysis was performed to identify the interactions between Til and its targeted biomarkers.

Til significantly reduced biochemical markers, fasting blood glucose, food intake, and kidney weight and elevated antioxidant enzymes in diabetic rats. It also mitigated inflammatory and fibrotic markers, lessened renal injury, and displayed inhibitory potential against crucial markers associated with DN as demonstrated by molecular docking analysis.

These findings suggest Til's potential as a therapeutic agent for DN treatment, highlighting its promise for future drug development.

Core Tip: Tiliroside (Til) demonstrates potent protective effects against diabetic nephropathy (DN) in rats, alongside glibenclamide. Through attenuating oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis, Til treatment significantly improves renal function and reduces biochemical markers associated with DN. Molecular docking analysis reveals its potential inhibition of key markers linked to the disease. These findings underscore Til's promising role as a therapeutic agent for DN, suggesting avenues for future drug development.

- Citation: Shang Y, Yan CY, Li H, Liu N, Zhang HF. Tiliroside protects against diabetic nephropathy in streptozotocin-induced diabetes rats by attenuating oxidative stress and inflammation. World J Diabetes 2024; 15(11): 2220-2236

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v15/i11/2220.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v15.i11.2220

Diabetes mellitus (DM), a prevalent and potentially fatal medical condition, has been linked to various cardiovascular disorders, including stroke, peripheral arterial disease, coronary heart disease, retinopathy, kidney disorder, and peripheral neuropathy[1]. The incidence of diabetes has elevated significantly over the world in recent decades as a consequence of alterations in lifestyle and socioeconomic development[2]. A serious chronic consequence of DM types 1 and 2 is diabetic nephropathy (DN), the leading global cause of dialysis, renal failure, and transplantation[3]. The prevalence of DN peaks after 10 to 20 years of diabetes and is a chronic kidney disease that gradually progresses[4]. DN, a metabolic illness, is the primary cause of end-stage renal failure, characterized by renal hyperfiltration, early microalbuminuria, and increased permeability to protein, urea, and macromolecules[5]. Modifiable risk factors include glycemic control, dyslipidemia, hypertension, age, ethnicity, and genetic profile, while inevitable factors include family history and men's higher risk[6].

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced in higher concentrations as a result of oxidative stress induced by hyperglycemia[7]. ROS cause cell membrane destruction, deactivation of anti-oxidant enzymes, and modifications in the expression of endogenous anti-oxidant genes, and contribute to the development of DN[8]. ROS trigger signal transduction cascades, causing profibrotic molecules like collagen IV, fibronectin, and lamin expression, and promoting extracellular matrix build-up and inflammatory gene expression. It also promotes tissue fibrosis and cell proliferation[9]. New research shows that angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors are effective in treating DN, halving renal disease risk by 45%, but adverse effects limit their clinical use[10].

Since hundreds of years ago, several medicinal plants have been employed often in the management of diabetes and its complications. For potential in vitro inhibitory actions on advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), various plant extracts have recently undergone screening[11]. Plant flavonoids exhibit anti-allergic, anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, anti-carcinogenic, antiviral, and anti-thrombotic properties, primarily due to their antioxidant activity, which involves chelation, elimination, and repression of ROS-producing enzymes[12]. A glycosidic flavonoid called Tiliroside (Til) is present in several food and medicine sources, including linden, rose hips, and strawberries[13]. There have been no reports of Til toxicity against non-cancerous cells, and it has been shown to have antioxidant, antiobesity, antidiabetic, and other properties[14].

Til, a flavonoid glycoside, has antioxidant properties and potential benefits in diabetes treatment, particularly DN. It modulates signaling pathways related to DN, including inflammation and apoptosis[15]. Til's antioxidant properties mitigate oxidative damage caused by hyperglycemia, which is crucial for DN pathogenesis. It also influences inflammatory pathways, potentially reducing inflammatory responses in DN[16]. Additionally, it reduces apoptosis in renal cells, preserving renal function. Further research is needed to understand its molecular mechanisms and potential clinical applications. Til's antioxidant effects also influence various inflammatory pathways, which are critical factors in DN[17]. By downregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines and pathways involved in inflammation, Til could potentially reduce inflammatory responses that exacerbate DN. Additionally, Til may reduce apoptosis in renal cells, which is a significant contributor to renal cell death in DN[18].

The primary goal of the current study was to evaluate Til's effectiveness against streptozotocin (STZ)-provoked diabetes in SD rats by examining the biochemical and histological markers. The impact of Til on levels of fasting blood glucose (FBG), food intake, body weight (BW), water intake, insulin, kidney weight, antioxidants and pro-inflammatory markers, biochemical markers, and fibrotic markers levels in untreated and treated rats was examined.

Glibenclamide (GB), Til, and STZ were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich in the United States. All of the other necessary chemicals and reagents were of high analytical category.

After receiving approval from the Institutional Review Board, mature healthy Wistar rats weighing 180-200 g were purchased from the Animal Facility. In a fully sanitary laboratory, the rat adaptation was carried out by keeping the temperature at 25 °C, the relative humidity at 55 °C for a duration of 1 wk, and the cycle of daylight and darkness for 12 h. Following adaptation, rats were fed regular rat food, and freshwater was always supplied. All experimental techniques utilized in the current study were approved by the local ethics committee, and the rats were handled with the utmost care.

Using the medication STZ, diabetes was triggered in the experimental animals. STZ (60 mg/kg) was intraperitoneally provided to the animals in a 0.1 M citrate buffer at pH 4.4. The blood glucose level was measured to verify the onset of diabetes after 7 d of STZ therapy. In the current experimental investigation, rats having a blood glucose value of more than 11 mmol/L were used.

Five groups of six rats each were used in the study. Groups were randomly split. The first group of rats (control group) received an intraperitoneal injection of about 0.5% of DMSO. The second group of rats received an intraperitoneal injection of the medication STZ at a dose of 60 mg/kg. The third group received Til (25 mg/kg body weight [bwt]) after being given STZ. The fourth group received Til (50 mg/kg bwt) after being given STZ. The fifth group received the anti-diabetic medication GB (600 μg/kg bwt) after being given STZ. GB and Til, dissolved in 0.5% DMSO, were given orally once daily in the morning for 60 d. Following the conclusion of the course of therapy, the rats were sacrificed, their blood was obtained for biochemical analysis, and their kidney, liver, and pancreas tissues were obtained for histological research.

The BW of the experimental animals was recorded on the 0th and final day of the experiment and compared between all experimental groups. On the 0th, 30th, and 60th days following the administration of medication, fasting blood samples were taken. Before measuring the FBG, the rats had a fast for an entire night. Precisely drawn orbital sinus blood samples were used to estimate glucose levels utilizing the glucose assessment kit.

Regular measurements of food and water consumption were taken for each group of rats during the course of the study. All of the rats in the group were killed under anesthetic circumstances (24 mg/kg BW of ketamine intramuscularly). Blood was extracted into collection tubes both with and without anticoagulants. Immediately after being separated, the kidney and liver were weighed and thoroughly cleansed in ice-cold saline to remove any blood. After that, 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer was used to yield a 10% homogenate, which was then centrifuged at 1000 g for a duration of 10 min. Tests on biochemical parameters were conducted using the isolated supernatants. An ELISA kit that is available commercially was used to measure the insulin levels in the test animals. A microplate ELISA reader was used to measure the final absorbance of the standard and sample at 450 nm just after the stop solution was added. The homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was employed to determine the level of plasma insulin resistance in the experimental animals. The subsequent formula was used to compute HOMA-IR using fasting glucose and insulin values: HOMA-IR = fasting glucose (mmol/L) × fasting insulin (uIU/mL)/22.5.

To evaluate the renal function, serum was centrifuged at 3600 g for 10 min. On an automated biochemical analyzer, the blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine (SCr) levels were measured. The levels of N-acetyl glucosamine (NAG), uric acid, and urinary microalbumin (U-mAlb) were measured from the collected urine samples by utilizing respective commercially available kits.

The levels of anti-oxidant biomarkers including glutathione peroxidase (GPx), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and glutathione (GSH) were estimated calorimetrically utilizing commercially available kits by following the protocols provided by the manufacturer. ELISA kits were used following the instructions provided by the manufacturer to determine the levels of plasma AGEs. The production of intracellular ROS in rat kidney homogenate was fluorometrically measured by oxidizing the nonfluorescent label 2,7-dichloro fluorescein diacetate (DCFDA) to the fluorescent products dichloro fluorescein (DCF). Briefly, 5 μmol/L DCF-DA was added to 30 µL of kidney homogenate in phosphate-buffered saline, and the mixture was then left to sit at room temperature for 30 min. Following that, the mean fluorescence intensity was directly measured at 485 nm and 535 nm for the excitation and emission wavelengths, respectively.

The levels of pro-inflammatory markers including interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) in each group were measured using commercial ELISA kits that were acquired from the market. The experiment followed the instructions given by the manufacturer. The experiment was done in triplicate, and the absorbance at 450 nm was determined. The standard curve with established standard concentrations was used to compute the final results.

The assessment of fibronectin and transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1) levels in the renal tissue was carried out utilizing ELISA kits. The renal cortex was centrifuged at a speed of 9000 rpm for a duration of 20 min at 4 °C after being instantly homogenized in ice-cold phosphate buffer saline with 0.05% Tween 20. The supernatants were then used to estimate the concentrations of fibronectin and TGF-β1 using ELISA kits that were commercially available.

All five investigation groups-Control, diabetic provoked, diabetic provoked and Til-treated (25 mg/kg and 50 mg/kg), and diabetic-provoked & GB-treated had their renal tissues subjected to histopathological analysis. Initial formalin (10%) treatment of the tissues was carried out for 24 h. The tissue was subsequently sliced into 3-5 µm thick sections with a rotary microtome, embedded in paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). The stained slides were subsequently observed using an Olympus light microscope.

All statistical analyses were completed using GraphPad Prism version 6.01. The results are reported as the mean ± SD. ANOVA and the Tukey post hoc test were used to check whether there were any differences between the groups. P values < 0.05 were deemed statistically significant.

Homology modeling and its validation: Due to the lack of three-dimensional (3D) structure for TGF-β1 (UniProt ID: Q3UNK5) in the PDB, the TGFβ1 structure was modeled using the alpha fold2 method integrated with the SWISS model. The Ramachandran plot (RP) is a highly valuable tool for validating protein structures. It displays the mapping of φ/ψ torsion angles of the polypeptide backbone in pairs against the predicted or "allowed" values. In this context, the modeled 3D structure of TGF-β1 was verified using RP to identify an amino acid corrosive in a protein structure by the use of Verify3D and ERRAT through SAVES server (https://saves.mbi.ucla.edu/; Accessed on 17 November 2023), which demonstrated specific details regarding the stability, consistency, and dependability of the protein's tertiary structure.

Active site prediction: The active sites for the described biomarkers, such as fibronectin and TGF-β1, were predicted using PrankWeb, which provides an interface to P2Rank, a template-free machine learning method to detect the ligand binding sites (http: //prankweb.cz/; accessed on 18 November 2023)[19].

Preparation of protein structure and ligand: The 3D structure of the described rat renal fibrotic markers such as fibronectin (PDB ID: 1MFN) and TGF-β1 (UniProt ID: Q3UNK5) and pro-inflammatory biomarkers such as IL-6 (PDB ID: 2 L3Y), TNF-α (PDB ID: 2TNF), and IL-1β (PDB ID: 4G6M) were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank and UniProt[20-23]. The water molecules and associated ligands were removed for the retrieved biomarkers using the Discovery Studio Visualizer v19.1.0.18287 (www.accelerys.com). The ligand Til was downloaded from the PubChem compound database[24] and saved in the SDF file format with the provided atomic coordinates and converted into PDB format using Discovery Studio Visualizer v19.1.0.18287 (www.accelerys.com).

After preparing the chemical compound Til as a ligand, and fibronectin (PDB ID: 1MFN), TGF-β1 (UniProt ID: Q3UNK5), IL-6 (PDB ID: 2 L3Y), TNF-α (PDB ID: 2TNF), and IL-1β (PDB ID: 4G6M) as targets, we used PyRx software to implement Autodock Vina for the molecular docking process. The docking propensity of Til and the interfaces between Til and the target residues are examined. The prepared targets and ligand were saved in PDBQT format. The size was assigned to the grid box properties as fibronectin (size_x = 23.44 Å, y = 20.53 Å, and size_z = 23.61 Å), TGF-β1 (size_x = 27.67 Å, y = 24.01 Å, and size_z = 23.00 Å), IL-6 (size_x = 28.37 Å, y = 25.22 Å, and size_z = 34.11 Å), TNF-α (size_x = 18.36 Å, y = 19.34 Å, and size_z = 18.64 Å), and IL-1β (size_x = 55.68 Å, y = 52.27 Å, and size_z = 51.22 Å). The PyRx virtual screening tool identified the interacted active site residues of the targeted biomarkers inhibited by Til. The interactions between Til and its targeted biomarkers were visualized in 3D by importing the docked data into PyMol, Lig-Plot+, and Discovery Studio Visualizer v19.1.0.1828 [Dassault Systèmes BIOVIA, Rue Marcel Dassault, Vélizy-Villacoublay-78140, France, www.accelerys.com (accessed on 20 November 2023)]. Additionally, the 2D diagram was obtained for the interacted ligand and targets using LigPlot+. A molecular docking study was carried out using Autodock Vina by utilizing PyRx which offers an integrated scoring algorithm.

Figure 1 depicts the impact of Til on the FBG level in the experimental animals on the 7th, 30th, and 60th days. On the 7th day, the level of blood glucose was almost the same for all the experimental groups except the control group. On the 30th day, the blood glucose level was decreased in all groups in comparison to the STZ-treated control animals (group II). Whereas on the 60th day, there was a significant decrease in the blood glucose level in animals treated with Til in a dose-based manner (groups III and IV). At the end of the study, there was no considerable change in the FBG level between the Til -treated and GB-treated animals.

Figure 2 depicts the effect of Til on the BW in STZ-treated rats. On the 0th day, the BW of the experimental animals in all the groups was the same. Group II (STZ-treated) animals showed a reduction in their BW in comparison to the STZ-induced animals treated with Til extract in a dose-dependent manner (group III and group IV). Til extract almost maintained the animal BW in group III and group IV.

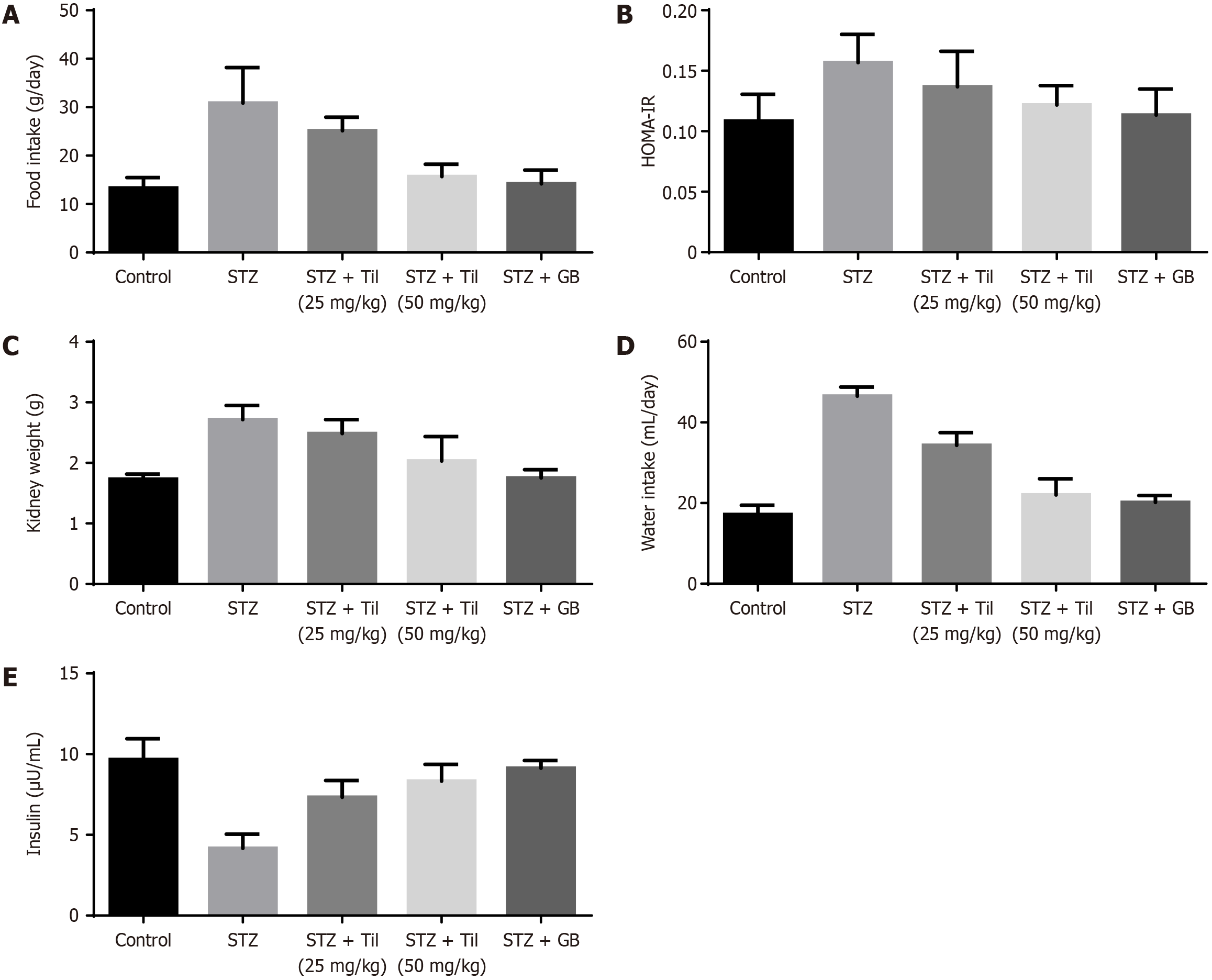

In the DR animals, the effects of Til medication on many parameters, including food intake, kidney weight, HOMA-IR, water consumption, and insulin levels, were investigated. The average food intake, HOMA-IR, kidney weight, and water consumption levels of the STZ-induced DR animals were shown to be higher when compared to those of control animals. In STZ-induced mice, Til treatment dramatically decreased food intake, HOMA-IR, kidney weight, and water con-sumption. Additionally, compared to rats exposed to STZ, Til treatment elevated the insulin level in animals (Figure 3). The effects of GB treatment were comparable to those of Til.

Figure 4 illustrates the effect of Til on the serum levels of BUN, SCr, uric acid, NAG, ROS, and microalbumin in STZ-treated rats. The findings revealed that 24 h after receiving STZ, the rats had acute nephrotoxicity as evidenced by a substantial rise in BUN, uric acid, SCr, NAG, and microalbumin levels. When rats with nephrotoxicity induced by STZ were treated with Til (group III and group IV), the levels of BUN, SCr, NAG, uric acid, and microalbumin were significantly decreased in a dose-dependent manner when compared with those of the STZ-treated animals (group II). The effects of GB treatment were comparable to those of Til.

The effect of Til treatment on the levels of different antioxidants in untreated and treated rats was evaluated. Figure 5 shows that STZ-stimulated animals had considerably decreased levels of antioxidants including SOD, GSH, and GPx in their retinal tissues when compared to control animals. It's noteworthy to note that Til treatment dramatically increased the SOD, GSH, and GPx in the STZ-induced rats. The level of ROS and plasma AGE level were elevated in the STZ-provoked animals in comparison to control rats. On treatment with Til, the levels of ROS and plasma AGEs were reduced. Administration of Til increased antioxidant state in the STZ-provoked DR rats.

The levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β were measured in the retinal tissues of untreated and treated rats and are shown in Figure 6. The levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β in the retinal tissues were significantly increased in the STZ-stimulated rats as compared to the control animals. When Til was administered as a supplement, the levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β expression in the STZ rats, however, significantly decreased (Figure 6). The expression of these markers in the retinal tissue of STZ-provoked animals was likewise decreased by GB treatment.

The 3D modeled structure of transforming growth factor-beta 1 (UniProt ID: Q3UNK5) is a crucial validation tool for 3D protein structures, assessing the quality of backbone conformation. It visualizes allowed and disallowed regions for dihedral angles, indicating rotation around bonds. Interpreting the Ramachandran Plot helps identify allowed and disallowed regions, red flags, and outliers (Figure 7).

Additionally, the molecular docking analysis was performed to identify the crucial interactions of Til with the described pro-inflammatory and renal fibrotic markers. In this context, we focused on the task of predicting active sites using the target 3D structures which include IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, fibronectin, and TGF-β1 (Figure 8). The predicted active site residues of the targets were finalized based on the first ranking method which uses the machine learning approach P2Rank (Table 1). The molecular docking analysis was performed between Til and the predicted active site of the targeted biomarkers. The resulting molecular docking analysis confirmed that Til interacted with the residues of IL-6 such as SER93 and ILE92 via hydrogen bond and pi-sigma bond formed with VAL136. Additionally, the pi-cation, pi-alkyl, and pi-pi T-shaped bonds formed with the residues such as CYs78, CYS88, and HIS 140. It was also surrounded by hydrophobic residues such as TYR83, ASN84, GLN85, GLU86, ILE87, LEU89, LEU90, LYS91, ASN133, PHE132, LEU139, and ILE142 with a binding affinity of -8.4 kcal/mol and root mean square distance (RMSD) of 2.652Å (Figure 8C and D; Table 2). Likely, Til interacted with TNF-α residues such as SER99, LYS112, and TYR115 via hydrogen bond with a binding affinity of -5.4 kcal/mol and RMSD of 1.816Å. Also, the pi-cation and pi-alkyl bonds formed with the residues CYS69 and LYS98. Additionally, the hydrophobic residues such as VAL97, GLU116, TRP114, GLY68, PRO113, PRO102, THR105, LYS103, PRO106, and LYS103 were surrounded with the Til-IL-6 complex (Figure 8E and F; Table 2). Also, Til interacted via hydrogen bonds with the residues of IL-1beta which include TYR24, LYS77(2), and LEU82(2). Likely, the pi-cation, pi-alkyl, and pi-pi sigma bonds are formed with the residues LYS74, PRO131, and PHE13(2). Also, the hydrophobic residues were surrounded by the Til-IL-1beta complex with a binding affinity of -7.5 kcal/mol and RMSD of 2.062Å (Figure 8G and H; Table 2).

| No. | Biomarker name | Targets (PDB ID) | Rank | Score | Probability | Predicted active sites |

| 1 | Fibronectin | 1MFN | 1 | 2.74 | 0.084 | HIS36, HIS37, ALA38, SER41, ARG46, ASN61, LEU62, ASN63, TYR68 |

| 2 | TGF-β1 | Q3UNK5 | 1 | 9.11 | 0.534 | ARG277, THR282, ASN283, ASN292, CYS293, CYS294, TRP330, ASP333, GLN359, SER386, CYS387, CYS389, PRO99 |

| 3 | IL-6 | 2 L3Y | 1 | 10.37 | 0.597 | ILE129, PHE132, ASN133, GLU135, VAL136, ILE142, LEU184, THR187, ARG188, THR27, VAL30, GLY31, LEU89, LEU90, LYS91, ILE92, SER93, LEU96 |

| 4 | TNF-α | 2TNF | 1 | 8.36 | 0.491 | PRO100, PRO102, TRP114, GLU116, LYS98, SER99 |

| Target name | Target PDB/UniProt ID | Binding affinity (kcal/mol) | RMSD (Å) | Type of interacted bonds | ||

| Hydrogen bond | Hydrophobic residues | Other bonds | ||||

| Fibronectin | 1MFN | -7.6 | 2.583 | ARG44, ASN61 | HIS37, HIS40, SER41, GLY43, PRO45, LEU62, ASN63, THR66, TYR68, | ALA38pa, ARG46 |

| IL-6 | 2 L3Y | -8.4 | 2.652 | ILE92, SER93(2) | LYS91, LEU89, ILE142, LEU90, ASN133, PHE132, LEU139, ILE87, GLU86, GLN85, TYR83, ASN84 | VAL136psa, CYC78ps, CYC88 Lps |

| TNF-α | 2TNF | -5.4 | 1.816 | SER99, TYR115, LYS112 | GLY68, VAL97, PRO102, LYS103, PRO105, PRO106, TRP114, PRO113, GLU116, | LYS98pc, ch, CYS69pa |

| IL-1β | 4G6M | -7.5 | 2.062 | TYR24, LYS77(2), LEU82(2) | GLU25, THR79, SER125, MET130, VAL132 | LYS74pc, PRO131pa, PHE133pps (2) |

| TGF-β1 | Q3UNK5 | -9.1 | 2.125 | GLU96, GLU100, ARG277, LEU280, THR282, ASN283, CYS293, GLN359 | PRO95, PRO99, SER274, ARG275, ARG278, ALA279, ASN292, CYS326, TRP330, SER386, CYS389, | GLU98pc, GLU100pc, ARG277ps, pa, ASN283ch, HIS276ch, ASP333ch |

The effect of Til treatment on fibrotic markers including TGF-β1 and fibronectin in untreated and treated rats was evaluated, as depicted in Figure 9. The levels of fibronectin and TGF-β1 were significantly increased in the STZ-stimulated rats as compared to the control animals. When Til was administered as a supplement, the levels of TGF-β1 and fibronectin in the STZ rats, however, considerably decreased. The effects of GB treatment were comparable to those of Til.

Due to the lack of TGF-β1 (Uniprot ID: Q3UNK5) structure, the Q3UNK5 structure was modeled, ranging between amino acid residues 1-390, using the TGF-β1 from Mustela putorious with a sequence identity of 90.00% (Figure 10A). The modeled TGF-β1 3D structure showed 87.8% residues in the most favored regions and 11.30% in additional allowed regions, indicating that the model can be taken into further study (Figure 10B). The molecular docking analysis of fibronectin found that that Til formed two hydrogen bonds with the residues ARG44 and ASN61 and a pi-alkyl bond with ALA38. Also, the Til-fibronectin complex surrounded by hydrophobic residues such as HIS37, HIS40, SER41, GLY43, PRO45, LEU62, ASN63, THR66, and TYR68 with a binding affinity of -7.6 kcal/mol and RMSD of 2.583Å (Figure 8A and B; Table 2). Above all, Til interacted well with the TGF-β1 via hydrogen bonds such as GLU96, GLU100, ARG277, LEU280, THR282, ASN283, CYS293, and GLN359 (Figure 10C-E). Also, the pi-cation bond formed with GLU98 and GLU100. The pi-sulfur and pi-alkyl bonds formed with ARG277. Additionally, the carbon-hydrogen bond formed with ASN283, HIS276, and ASP333 with a binding affinity of -9.1 kcal/mol and RMSD of 2.125Å (Figure 8I and J; Table 2). The overall resulting binding affinity, RMSD, interacting residues, and the types of bonds formed between the targeted biomarkers and Til are listed in Table 2.

The renal tissues from animals treated with Til and GB as well as control animals underwent histological examination (Figure 11). Renal tissues stained with H&E showed that STZ caused glomeruli to contract and necrotize, renal tubular epithelial cells to be damaged, edema, and neutrophil infiltration. When Til (groups III and IV) and GB (group V) were given to diabetic rats, histological alterations such as edema, tubular and glomerular injury, and neutrophil penetrations in the renal tissues were all minimized.

In individuals with type 1 or type 2 DM, nephropathy continues to be a major source of morbidity and significant predictor of death. The development of proteinuria, which is usually accompanied by a gradual deterioration in renal function, is one of the characteristics of DN. From an epidemiological, pathophysiological, and clinical standpoint, the condition is typically accompanied by high blood pressure and poor glycemic control[25]. Numerous investigations on diabetes and its consequences frequently employ the STZ-induced mouse model of the disease[26]. Investigations dependent on the pathogenic components of DN have led to the development of many new therapy options, including intensive glycemic management, precise control of blood pressure, ideal renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockade with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/ARBs, nutritional and physical activity, and a large number of novel agents[27]. Nowadays, many medications are derived from plants since they offer therapeutic benefits and are often devoid of side effects. Several chemical substances found in plants that are utilized for the treatment of DN include glycosides, alkaloids, terpenoids, and flavonoids[28]. The emphasis of the current study was to investigate the way that a naturally occurring substance called Til affected the progression of problems related to diabetes in STZ-stimulated SD rats. To compare Til's anti-diabetic activity, GB, a common medication, was used.

STZ, a pancreatic medication that kills the cells located in the islets of Langerhans, was administered to SD rats as part of this investigation. As a result, the amount of insulin secreted significantly decreased while blood glucose levels surged[29]. A significant increase in fasting blood sugar was observed after STZ treatment, and these findings are consistent with previous research[30]. In the current investigation, treatment with Til significantly reduced the level of fasting glucose in the STZ-provoked animals in a dose-based manner. This finding demonstrates the anti-diabetic properties of Til. Animals treated with STZ develop diabetic conditions and it is related to excessive weight loss due to hypoinsulinemia, increased muscle wasting, hyperglycemia, and loss of tissue proteins[31]. After receiving Til medication, the BW of STZ-diabetic rats dramatically increased, showing that the hyperglycemia-related deterioration of muscle tissue had been prevented.

A significant reduction in insulin levels was observed after STZ treatment, and these findings are consistent with previous research[32]. Interstitial atrophy and vasodilated atrophic alterations in the glomeruli and tubules contribute to an increased kidney weight as diabetes progresses[33]. HOMA-IR is calculated to evaluate resistance to insulin by the animals. A high HOMA-IR value indicates high resistance to insulin. The consumption of food and water was consi

It is important to boost both enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants in the body to counteract oxidative stress, which is the main reason causing the challenges to occur[37]. Antioxidant enzymes, such as GPx, SOD, and catalase (CAT), are the most important components of the defense system and actively contribute to ROS homeostasis. SOD is engaged in the catalysis of superoxide radical degradation, whereas GPx and CAT enzymes catalyze the decomposition of H2O2 to create oxygen and water. GSH reductase catalyzes the conversion of GSH disulfide to GSH sulfhydryl, which is essential for avoiding oxidative stress[38]. The reduction in antioxidant enzyme activities in diabetic rats has been demonstrated in several studies, and it may be caused by prolonged hyperglycemia-induced ROS production that leads to the decline of antioxidants[39]. Potentially effective treatment options for DN include inhibiting the generation of AGEs, suppressing receptor for AGEs (RAGE) expression, or blocking RAGE downstream signaling[40]. In the present investigation, the levels of antioxidant enzymes including SOD, GSH, and GPx were elevated on treatment with Til. The level of ROS was reduced. This demonstrates the antioxidant properties of Til. In addition, the level of AGE was also reduced in Til-treated animals in comparison to the treated control group. This indicates that Til can be a potent therapeutic for treating DN.

The occurrence of DN is influenced by inflammatory cytokines including IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α. Additionally, IL-1β is speculated to contribute to the development of intraglomerular hemodynamic abnormalities linked to prostaglandin production. Increased fibronectin levels, accelerated mesangial cell proliferation, altered extracellular matrix dynamics, and increased endothelial permeability are all effects of IL-6[41]. The onset and progression of renal damage in DN have been linked to TNF-α, a strong pro-inflammatory cytokine. It stimulates swelling, the build-up of the extracellular matrix, and impairment of the glomerular permeability barrier, which results in the onset of albuminuria[42]. The levels of these inflammatory mediators significantly decreased after Til treatment in diabetic rats, indicating that the drug may have anti-inflammatory properties. During renal damage, fibronectin expression is enhanced. TGF-β, a cytokine that plays a role in the formation of the ECM along with fibronectin, is regarded as the most effective pro-fibrotic molecule. Even though TGF-β and its three isoforms exist, TGF-1β is known to play a part in renal fibrosis. The expression of TGF-1β is elevated in DN[43]. Til treatment was successful in downregulating the levels of fibronectin and TGF-1β.

This study has several limitations, such as the absence of full replication of human DN in the in vitro model and a specific lack of capture of all aspects of the disease in the in vivo model. Studies of Til treatment have been based on specific dosages and durations, there is still confusion about the precise molecular mechanisms, and in silico docking analysis only provides insights into molecular interactions. There is much value in translating animal models to human clinical practice, and larger sample sizes would be able to provide more robust data in the future.

Our histological findings showed injuries to renal tubular epithelial cells, shrinkage and necrosis of glomeruli, swelling, and neutrophil infiltration in STZ-treated rats, which were consistent with the biochemical data and those from other investigations. Reduced glomerular and tubular injury, edema, and neutrophil penetrations in the renal tissues were all seen as a result of Til therapy in a dose-dependent manner. Also, the molecular docking analysis confirmed that there is a good interaction between Til and the targeted biomarkers including fibronectin, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, and TGF-β1. Specifically, Til highly interacted with TGF-β1.

Our research showed that Til reduced inflammatory mediators, blood glucose levels, and oxidative stress, enhanced antioxidants, and inhibited ROS to attenuate the STZ-induced DN in rats. These results validated the suggestion that Til could be a promising treatment for DN. However, further research will be required in the future to produce further evidence of the benefits of Til in DN.

The authors acknowledge their research institutes for the technical support.

| 1. | Tomic D, Shaw JE, Magliano DJ. The burden and risks of emerging complications of diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2022;18:525-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 771] [Cited by in RCA: 617] [Article Influence: 154.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yang X. Design and optimization of crocetin loaded PLGA nanoparticles against diabetic nephropathy via suppression of inflammatory biomarkers: a formulation approach to preclinical study. Drug Deliv. 2019;26:849-859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ninčević V, Zjalić M, Kolarić TO, Smolić M, Kizivat T, Kuna L, Včev A, Tabll A, Ćurčić IB. Renoprotective Effect of Liraglutide Is Mediated via the Inhibition of TGF-Beta 1 in an LLC-PK1 Cell Model of Diabetic Nephropathy. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2022;44:1087-1114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sagoo MK, Gnudi L. Diabetic Nephropathy: An Overview. Methods Mol Biol. 2020;2067:3-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 41.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Alhaider AA, Korashy HM, Sayed-Ahmed MM, Mobark M, Kfoury H, Mansour MA. Metformin attenuates streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy in rats through modulation of oxidative stress genes expression. Chem Biol Interact. 2011;192:233-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lim AKh. Diabetic nephropathy - complications and treatment. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2014;7:361-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 414] [Article Influence: 34.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zou J, Yu X, Qu S, Li X, Jin Y, Sui D. Protective effect of total flavonoids extracted from the leaves of Murraya paniculata (L.) Jack on diabetic nephropathy in rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2014;64:231-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Swaminathan S, Shah SV. Novel approaches targeted toward oxidative stress for the treatment of chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2008;17:143-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhang S, Xu H, Yu X, Wu Y, Sui D. Metformin ameliorates diabetic nephropathy in a rat model of low-dose streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Exp Ther Med. 2017;14:383-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Huang WJ, Liu WJ, Xiao YH, Zheng HJ, Xiao Y, Jia Q, Jiang HX, Zhu ZB, Xia CH, Han XT, Sun RX, Nan H, Feng ZD, Wang SD, Zhao JX. Tripterygium and its extracts for diabetic nephropathy: Efficacy and pharmacological mechanisms. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;121:109599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rahman MS, Hosen ME, Faruqe MO, Khalekuzzaman M, Islam MA, Acharjee UK, Bin Jardan YA, Nafidi HA, Mekonnen AB, Bourhia M, Zaman R. Evaluation of Adenanthera pavonina-derived compounds against diabetes mellitus: insight into the phytochemical analysis and in silico assays. Front Mol Biosci. 2023;10:1278701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schinella GR, Tournier HA, Máñez S, de Buschiazzo PM, Del Carmen Recio M, Ríos JL. Tiliroside and gnaphaliin inhibit human low density lipoprotein oxidation. Fitoterapia. 2007;78:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Goto T, Horita M, Nagai H, Nagatomo A, Nishida N, Matsuura Y, Nagaoka S. Tiliroside, a glycosidic flavonoid, inhibits carbohydrate digestion and glucose absorption in the gastrointestinal tract. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2012;56:435-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Grochowski DM, Locatelli M, Granica S, Cacciagrano F, Tomczyk M. A Review on the Dietary Flavonoid Tiliroside. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2018;17:1395-1421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hu Q, Qu C, Xiao X, Zhang W, Jiang Y, Wu Z, Song D, Peng X, Ma X, Zhao Y. Flavonoids on diabetic nephropathy: advances and therapeutic opportunities. Chin Med. 2021;16:74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Caturano A, D'Angelo M, Mormone A, Russo V, Mollica MP, Salvatore T, Galiero R, Rinaldi L, Vetrano E, Marfella R, Monda M, Giordano A, Sasso FC. Oxidative Stress in Type 2 Diabetes: Impacts from Pathogenesis to Lifestyle Modifications. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2023;45:6651-6666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 87.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Xue R, Xiao H, Kumar V, Lan X, Malhotra A, Singhal PC, Chen J. The Molecular Mechanism of Renal Tubulointerstitial Inflammation Promoting Diabetic Nephropathy. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2023;16:241-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ma X, Ma J, Leng T, Yuan Z, Hu T, Liu Q, Shen T. Advances in oxidative stress in pathogenesis of diabetic kidney disease and efficacy of TCM intervention. Ren Fail. 2023;45:2146512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jendele L, Krivak R, Skoda P, Novotny M, Hoksza D. PrankWeb: a web server for ligand binding site prediction and visualization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W345-W349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 38.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Copié V, Tomita Y, Akiyama SK, Aota S, Yamada KM, Venable RM, Pastor RW, Krueger S, Torchia DA. Solution structure and dynamics of linked cell attachment modules of mouse fibronectin containing the RGD and synergy regions: comparison with the human fibronectin crystal structure. J Mol Biol. 1998;277:663-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Baeyens KJ, De Bondt HL, Raeymaekers A, Fiers W, De Ranter CJ. The structure of mouse tumour-necrosis factor at 1.4 A resolution: towards modulation of its selectivity and trimerization. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:772-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Veverka V, Baker T, Redpath NT, Carrington B, Muskett FW, Taylor RJ, Lawson AD, Henry AJ, Carr MD. Conservation of functional sites on interleukin-6 and implications for evolution of signaling complex assembly and therapeutic intervention. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:40043-40050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Blech M, Peter D, Fischer P, Bauer MM, Hafner M, Zeeb M, Nar H. One target-two different binding modes: structural insights into gevokizumab and canakinumab interactions to interleukin-1β. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:94-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kim S, Chen J, Cheng T, Gindulyte A, He J, He S, Li Q, Shoemaker BA, Thiessen PA, Yu B, Zaslavsky L, Zhang J, Bolton EE. PubChem 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51:D1373-D1380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1785] [Article Influence: 446.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fineberg D, Jandeleit-Dahm KA, Cooper ME. Diabetic nephropathy: diagnosis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9:713-723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kitada M, Ogura Y, Koya D. Rodent models of diabetic nephropathy: their utility and limitations. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2016;9:279-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sun GD, Li CY, Cui WP, Guo QY, Dong CQ, Zou HB, Liu SJ, Dong WP, Miao LN. Review of Herbal Traditional Chinese Medicine for the Treatment of Diabetic Nephropathy. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:5749857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Shahin D H H, Sultana R, Farooq J, Taj T, Khaiser UF, Alanazi NSA, Alshammari MK, Alshammari MN, Alsubaie FH, Asdaq SMB, Alotaibi AA, Alamir AA, Imran M, Jomah S. Insights into the Uses of Traditional Plants for Diabetes Nephropathy: A Review. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2022;44:2887-2902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hamza RZ, Al-eisa RA, El-shenawy NS. RETRACTED: Efficacy of Mesenchymal Stem Cell and Vitamin D in the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus Induced in a Rat Model: Pancreatic Tissues. Coat. 2021;11:317. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hao HH, Shao ZM, Tang DQ, Lu Q, Chen X, Yin XX, Wu J, Chen H. Preventive effects of rutin on the development of experimental diabetic nephropathy in rats. Life Sci. 2012;91:959-967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Mestry SN, Dhodi JB, Kumbhar SB, Juvekar AR. Attenuation of diabetic nephropathy in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats by Punica granatum Linn. leaves extract. J Tradit Complement Med. 2017;7:273-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Dhaliwal J, Dhaliwal N, Akhtar A, Kuhad A, Chopra K. Beneficial effects of ferulic acid alone and in combination with insulin in streptozotocin induced diabetic neuropathy in Sprague Dawley rats. Life Sci. 2020;255:117856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Wang J, Liu H, Li N, Zhang Q, Zhang H. The protective effect of fucoidan in rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy. Mar Drugs. 2014;12:3292-3306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Azarkish F, Hashemi K, Talebi A, Kamalinejad M, Soltani N, Pouladian N. Effect of the Administration of Solanum nigrum Fruit on Prevention of Diabetic Nephropathy in Streptozotocin-induced Diabetic Rats. Pharmacognosy Res. 2017;9:325-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kokate D, Marathe P. Evaluation of Effect of Montelukast in the Model of Streptozotocin Induced Diabetic Nephropathy in Rats. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2024;28:47-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Jiang T, Wang L, Ma A, Wu Y, Wu Q, Wu Q, Lu J, Zhong T. The hypoglycemic and renal protective effects of Grifola frondosa polysaccharides in early diabetic nephropathy. J Food Biochem. 2020;44:e13515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Lubrano V, Balzan S. Enzymatic antioxidant system in vascular inflammation and coronary artery disease. World J Exp Med. 2015;5:218-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Nna VU, Bakar ABA, Mohamed M. Malaysian propolis, metformin and their combination, exert hepatoprotective effect in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Life Sci. 2018;211:40-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Giribabu N, Eswar Kumar K, Swapna Rekha S, Muniandy S, Salleh N. Vitis vinifera (Muscat Variety) Seed Ethanolic Extract Preserves Activity Levels of Enzymes and Histology of the Liver in Adult Male Rats with Diabetes. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:542026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Kim YS, Jung DH, Sohn E, Lee YM, Kim CS, Kim JS. Extract of Cassiae semen attenuates diabetic nephropathy via inhibition of advanced glycation end products accumulation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Phytomedicine. 2014;21:734-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Xie R, Zhang H, Wang XZ, Yang XZ, Wu SN, Wang HG, Shen P, Ma TH. The protective effect of betulinic acid (BA) diabetic nephropathy on streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats. Food Funct. 2017;8:299-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Barzegar-Fallah A, Alimoradi H, Asadi F, Dehpour AR, Asgari M, Shafiei M. Tropisetron ameliorates early diabetic nephropathy in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2015;42:361-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Malik S, Suchal K, Khan SI, Bhatia J, Kishore K, Dinda AK, Arya DS. Apigenin ameliorates streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy in rats via MAPK-NF-κB-TNF-α and TGF-β1-MAPK-fibronectin pathways. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2017;313:F414-F422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/