Published online Apr 15, 2021. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v12.i4.407

Peer-review started: October 10, 2020

First decision: December 12, 2020

Revised: January 20, 2021

Accepted: March 22, 2021

Article in press: March 22, 2021

Published online: April 15, 2021

Processing time: 180 Days and 23.3 Hours

Chronic disease management requires achievement of critical individualised targets to mitigate again long-term morbidity and premature mortality associated with diabetes mellitus. The responsibility for this lies with both the patient and health care professionals. Care plans have been introduced in many healthcare settings to provide a patient-centred approach that is both evidence-based to deliver positive clinical outcomes and allow individualised care. The Alphabet strategy (AS) for diabetes is based around such a care plan and has been evidenced to deliver high clinical standards in both well-resourced and under-resourced settings. Additional patient educational resources include special care plans for those people with diabetes undertaking fasting during Ramadan, Preconception Care, Prevention and Remission of Diabetes. The Strategy and Care Plan has facilitated evidence-based, cost-efficient multifactorial intervention with an improvement in the National Diabetes Audit targets for blood pressure, cholesterol levels and glycated haemoglobin. Many of these attainments were of the standard seen in intensively treated cohorts of key randomized controlled trials in diabetes care such as the Steno-2 and United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study. This is despite working in a relatively under-resourced service within the United Kingdom National Health Service. The AS for diabetes care is a useful tool to consider for planning care, education of people with diabetes and healthcare professional. During the time of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic the risk factors for the increased mortality observed have to be addressed aggressively. The AS has the potential to help with this aspiration.

Core Tip: The alphabet strategy for diabetes care is a very useful tool for the effective long-term management of patients with diabetes. It is based on; advice on lifestyle, blood pressure targets, cholesterol targets and chronic kidney disease prevention, diabetes control, eyecare, footcare, guardian drugs where indicated. This is achieved through an approach that is similar for both health care professionals (HCP) and patients. This is achieved through care planning, HCP guidelines and specialised care plans (for Ramadan, for example). It is an evidence based, patient centred, health care professional assisted, low-cost approach for treatment of diabetes and prevention of long-term diabetes complications.

- Citation: Upreti R, Lee JD, Kotecha S, Patel V. Alphabet strategy for diabetes care: A checklist approach in the time of COVID-19 and beyond. World J Diabetes 2021; 12(4): 407-419

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v12/i4/407.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v12.i4.407

One of the major global public health burdens of this current era, with over 450 million people affected globally, is type 2 diabetes mellitus[1]. Advances in acute care have led to increased life expectancy for patients with diabetes through excellent emergency management of conditions such as acute coronary syndrome, stroke and sepsis. The challenge now is to effectively manage their chronic disease to reduce the other complications of diabetes[1]. This has become especially important as the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic continues to spread globally with diabetes mellitus being identified as a significant risk factor for mortality (increased risk: × 2.86 for type 1 diabetes, × 1.80 for type 2 diabetes)[2]. Additionally, poor glycaemic control, obesity, Black and South Asian ethnicities, and chronic kidney disease (CKD) were identified as significant risks for increased mortality in patients with diabetes and COVID-19[3].

A multifactorial approach for diabetes management to reduce complications is encouraged in the United Kingdom through the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network guidelines and the National Diabetes Audit (NDA). A recent report published by NDA showed that meeting all three treatment targets (glycated haemoglobin, blood pressure, statin prescription) was only achieved in 19.6% for type 1 diabetes and 40.5% for type 2 diabetes patients (In England)[4]. Our institutional average of meeting these targets was 46.5%. It also observed that the percentage of patients receiving NICE recommended care processes has not shown significant improvement from 2012 to 2019.

“Care planning” involves the process by which both health care workers and patients have detailed discussions on the condition that the patient has. An individualized plan of management is then agreed based on the patient’s personal values and aspirations for their life. The written document after this process of planning is the “Care plan”[5]. The action plan and interventions required to manage an acute condition are very different than what is required to manage a chronic condition. At the same time, all chronic conditions, may if they differ in the involvement of organs of human body, have a common set of problems which need to be addressed by patient, their families and health carers. This concept is motivated by the physical, psychological and social needs which arise due to the chronic conditions of the patients. Care planning may save the enormous expenditure on chronic diseases which usually runs in billions of pounds[6]. It is important to remember that in an average year of 8766 h, a patient with diabetes will only spend approximately 45 to 90 min with a health care professionals (HCP). This could be two to four appointments of 10-30 min each, rest of the 8764.5 h in the year the patient has to self-manage (personal data based on clinic survey).

Care planning is not only being implemented across different countries but also across different specialties. Though care planning can be distinguished in terms for the conditions or for the patients, in usual practice it is most often for a condition-specific basis[5]. The care planning content can reflect the perspective of health professional or patient, the extent of the plan to which the behaviour change is intended, and the spread of the plan (i.e. involving only doctor-patient or involving doctor-patient-multidisciplinary teams/social teams)[7]. Care planning also involves behaviour change and subsequent other techniques to sustain those behaviour changes[8]. Care plans are considered to be one of the best tools for standardisation of care processes[5]. Prompts on electronic records such as those used in general practice in United Kingdom also serve this purpose.

Rawshani et al[9] investigated the increased risk of cardiovascular events and mortality in type 2 diabetes patients in comparison to general population[9]. This study was conducted on 271174 patients with type 2 diabetes from the Swedish National Diabetes Register who were matched with 1355870 controls without diabetes. The strongest predictors for combined cardiovascular outcomes and death were- current smoking, blood pressure (BP) ≥ 140/80 mmHg, low-density lipoprotein ≥ 2.5 mmol/L, albuminuria (micro or macro), HbA1c ≥ 53 mmol/mol. Each of these five factors increased the risk of acute myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure and mortality in patients with diabetes. The more the number of these risk factors present in a patient with diabetes, the higher was the risk observed for both unfavourable cardiovascular outcomes and mortality in comparison to the control group. This study reflects that multifactorial intervention in patients with diabetes may strongly impact in not only decreasing the adverse cardiovascular outcomes, but also reducing the mortality in diabetic patients. In the cohort < 55 years of age, the results showed that the increased risk in those with none of these five risk factors vs those with all 5 of the risk factors was: (1) excess mortality × 4.99; (2) excess myocardial infarction × 11.35; (3) excess stroke × 7.69; and (4) excess heart failure × 7.69.

Similar results were obtained from the follow-up Steno-2 study which recruited 160 patients with type 2 diabetes with microalbuminuria[10,11]. There were two randomized groups- one group receiving conventional multifactorial treatment and other group receiving intensified target driven therapy (targets included HbA1c, fasting serum total cholesterol and triglyceride levels, systolic and diastolic BP). At the start of the initial trial both groups were similar at baseline but developed significant differences by the end, showing that the intensive therapy was better than conventional therapy in attaining the set targets. In the follow up trial, both groups had received the intensive therapy and the gap of differences was observed to be narrowed by the end of the follow-up trial. The conclusions from the entire trial suggested that there is an absolute risk reduction (ARR) of 20% for death from any cause and an ARR of 29% for cardiovascular events in the intensive therapy group. Moreover, progression of diabetic complications was significantly reduced in the intensive therapy group.

The checklist approach for patient management has been rewarding in other specialties as well. Haynes et al[12] used a two-step surgical checklist in eight hospitals eight cities in different geographical parts of the world[12]. Their intervention with the checklist showed marked improvements in outcomes as reduction of major surgical complications and rate of death.

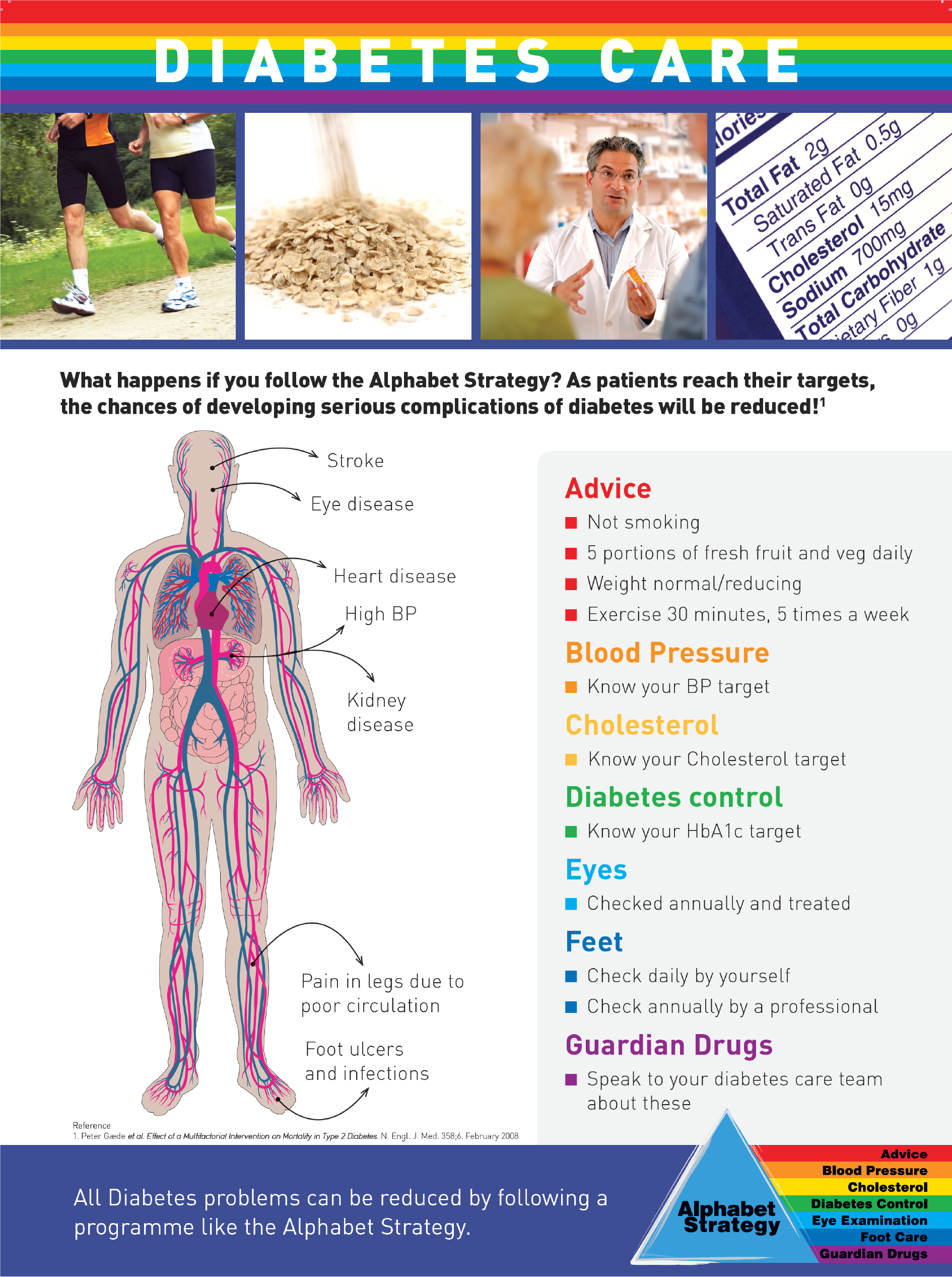

Our innovation in diabetes care was the “Alphabet strategy” (AS), which aimed for “simple things to be done right all the time”[13]. It is a mnemonic based checklist incorporating the core diabetes care components[14]; and includes the following (Figure 1): (1) advice on lifestyle: Diet, weight, and physical activity optimisation, not smoking, safe alcohol use, appropriate infection control [and very specifically vs severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)], nationally advised vaccinations (such as against influenza, SARS-CoV-2, pneumococcus); (2) BP: < 140/80 mmHg, ≤ 130/80 mmHg if kidneys or eyes affected or any cardiovascular disease; (3) cholesterol and CKD prevention: Total cholesterol ≤ 4 mmol/L, screening for and treating microalbuminuria; (4) diabetes control: HbA1c ≤ 58 mmol/mol or an individualised target, avoiding hypoglycaemia and hyperglycaemia interventions (for example diabetes ketoacidosis). Individualised glucose monitoring plans; (5) eye examination: check yearly at least, with referral if indicated; (6) foot care: Daily inspection and examination by patient and yearly examination by HCP; and (7) guardian drugs: Aspirin, clopidogrel and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers as indicated for primary and secondary preventions of cardiovascular and renal diseases.

The first version of the AS was published in 2002[14]. Since then the clinical guidance and Care Plans have been updated yearly. The strategy has proven to be adaptable and it has been relatively straight forward to adapt it to even the COVID-19 pandemic. Because of the curtailment in services during the COVID-19 pandemic we have incorporated an H for Healthcare Professional advice as follows.

Healthcare Professional advice: Especially for problems such as recurrent hypoglycaemia, recurrent diabetic keto-acidosis, difficulty accessing care (including affordability), Ramadan advice, pre-conception advice, driving and occupational advice, remission of diabetes.

The clinical impact of AS was assessed by two audits done in outpatient settings of a district level hospital in United Kingdom. The first audit involved 420 patients with diabetes who were followed over 5 years. The second audit, performed 2 years after the completion of the first audit, involved 1071 patients with diabetes. Comparison of the outcomes of the two audits showed improvement in all AS components (Table 1). An audit conducted in a low-income country (India), with 100 patients with diabetes in an outpatient clinic, also demonstrated the effectiveness of AS (Table 2).

| Alphabet strategy | Baseline audit, n = 420 | Follow-up audit, n = 1071 | P value | |

| A | Smoking status (%) | 15.5 | 14.7 | 0.83 |

| B | Blood pressure (mmHg) | 141/77 | 136/76 | 0.007 |

| C | Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.9 | 4.5 | < 0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 2.5 | 2.4 | < 0.001 | |

| Creatinine (mmol/L) | 109 | 105 | 0.036 | |

| D | HbA1c (%) (mmol/mol) | 8.3 (67.2) | 7.9 (62.8) | 0.09 |

| E | Eye examination (%) | 95.5 | 97.1 | 0.72 |

| F | Foot examination (%) | 83.5 | 97.3 | < 0.001 |

| G | Aspirin (%) | 83.5 | 88.0 | 0.20 |

| ACEI/ARB (%) | 73.0 | 74.4 | 0.75 | |

| Lipid lowering (%) | 55.0 | 73.4 | < 0.001 | |

| Pre implementation (%) | Post implementation (%) | P value | ||

| A | Body mass index | 99 | 99 | NS |

| Smoking status | 99 | 99 | NS | |

| Smoking cessation | 100 | 100 | NS | |

| B | Blood pressure | 99 | 99 | NS |

| C | Total cholesterol | 60 | 99 | < 0.001 |

| Lipid profile | 10 | 64 | < 0.001 | |

| Creatinine | 5 | 49 | < 0.001 | |

| Proteinuria | 48 | 93 | < 0.001 | |

| D | Fasting and postprandial glucose | 41 | 97 | < 0.001 |

| E | Eye examination | 98 | 100 | NS |

| F | Feet examination | 95 | 100 | NS |

| G | Aspirin therapy | 6 | 71 | < 0.001 |

| ACEI/ARB therapy | 7 | 57 | < 0.001 | |

| Statin therapy | 5 | 38 | < 0.001 | |

| All three | 2 | 20 | < 0.001 |

The potential of AS was globally assessed by a survey carried out in the Global AS Implementation Audit. It involved 4537 patients from 52 centres across 32 countries. The data showed that the strategy was highly acceptable to both patients and their healthcare professionals in high, middle and lower income countries.

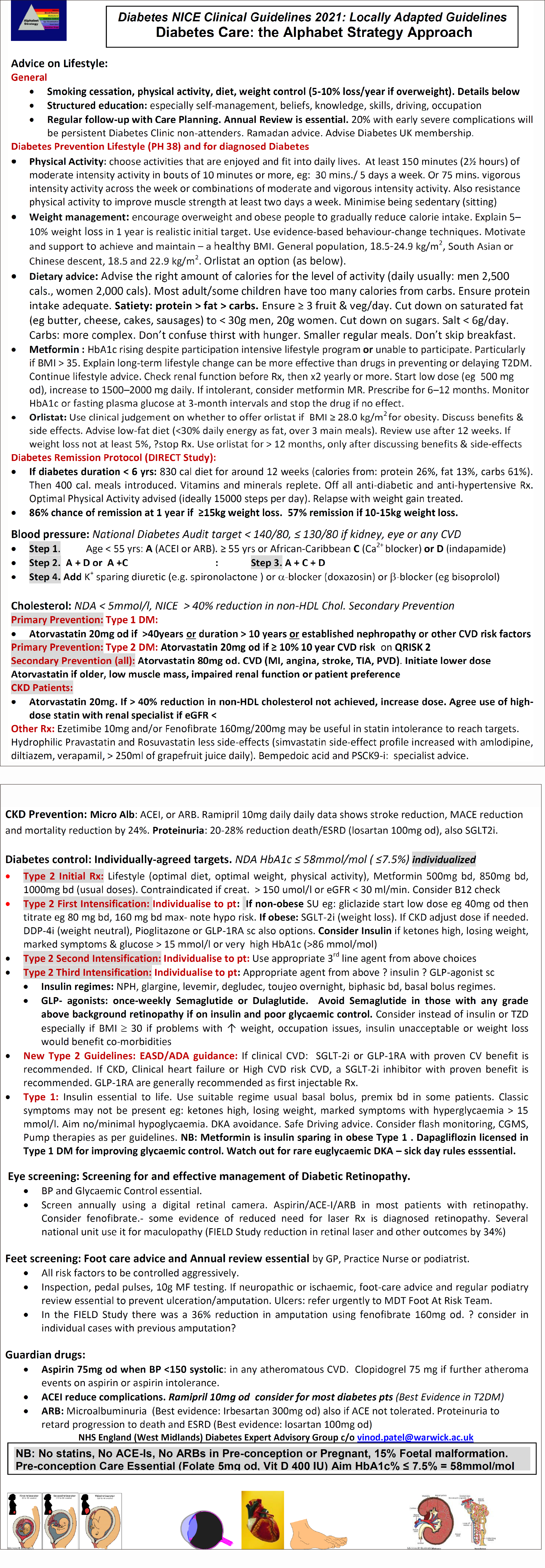

This new care plan was developed with the National Health Service (NHS) England and NHS Improvement West Midlands our Region Diabetes Expert Advisory Group, Right Care, and the Pharmacy Local Professional Network Chair (Figure 2).

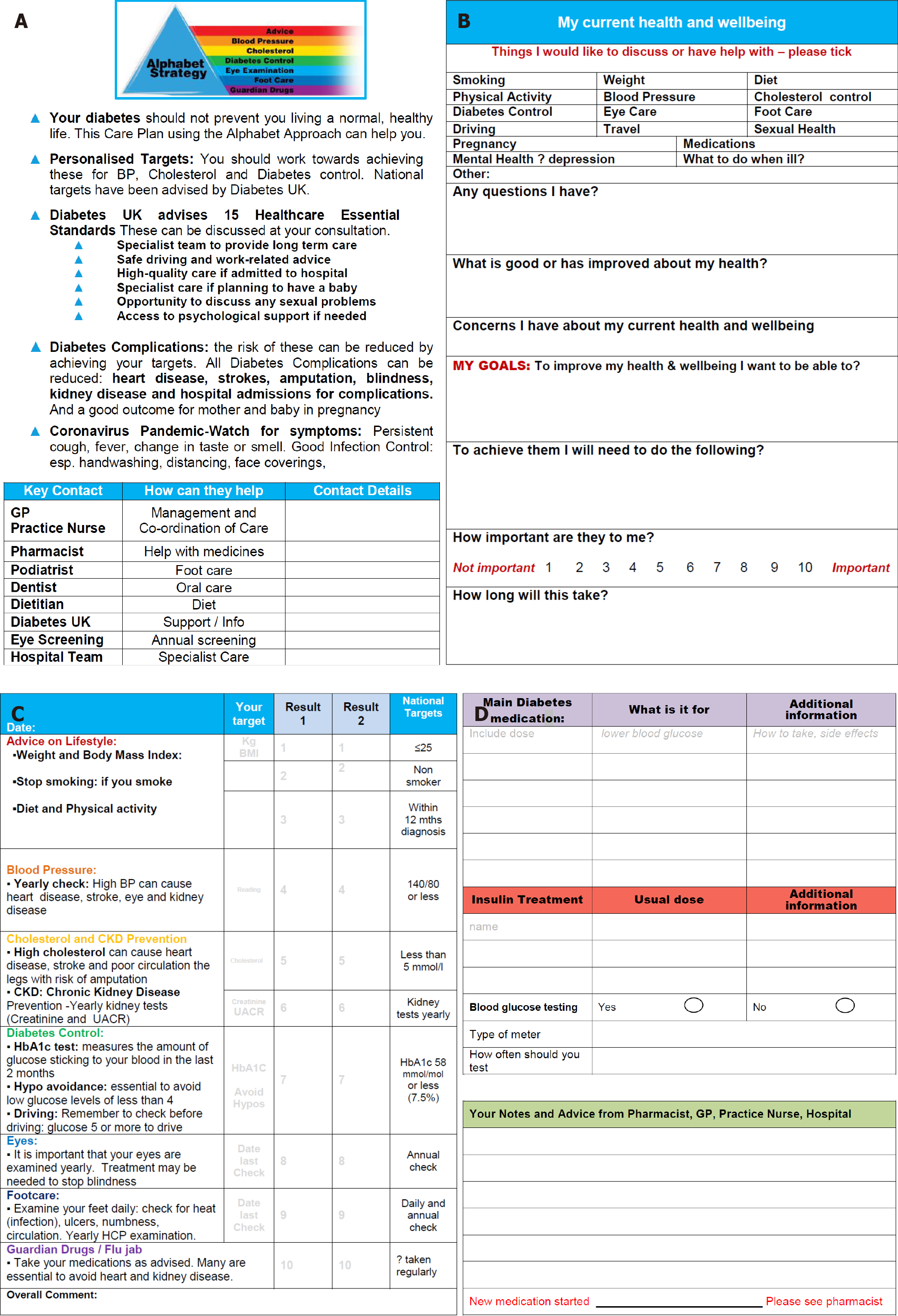

The AS core training materials (slides, documents and videos) have been created to facilitate and disseminate the programme. The training pack distributed to individual patient groups such as Diabetes United Kingdom (Figure 3) consists of:

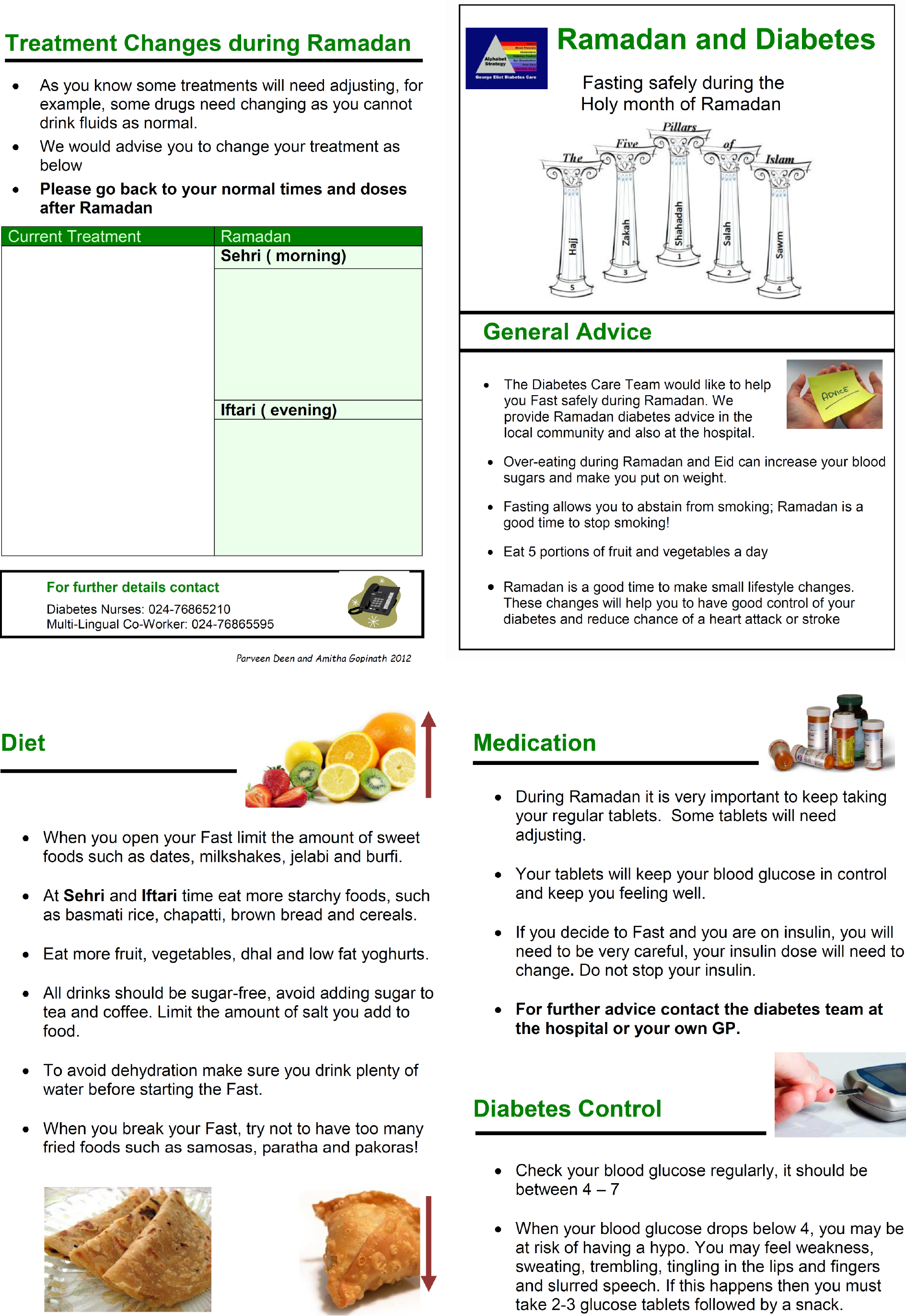

Patient education posters: Educate the patients about the AS overall. There is a similar poster for diabetes care for specifically during Ramadan developed with the South Asian Health Foundation (Figure 4).

Patient care plans: Empowering to know their NDA target and improve self-efficacy in attaining these. It also guides the important steps for pregnant patients to reduce complications (maternal and foetal). The main components of the care plan are as follows: (1) background information: Personal targets based on NDA, Diabetes United Kingdom 15 Healthcare Essentials, Key contacts; (2) patient’s agenda: Tick section for patients to indicate points for discussion, Questions to reflect on health status and specific goals; (3) patient’s personal agenda: Aspects of care to be documented such as BP, Cholesterol, Creatinine and Urine Albumin Creatinine Ratio, HbA1c, eye screening, feet examination, guardian drugs; (4) drugs and glucose monitoring: The HCP should advice on the dosing, frequency and side effects of any new drugs started for the patient. Advice for the patient on monitoring of blood glucose with an appropriate Glucose Testing Meter including frequency of monitoring. Patient should have Community Pharmacist review also where available; and (5) contact details: There is a list of the important contact details for the key specialists/organizations related to diabetic patient management.

One page guideline: Summary of one-page current NICE guidelines in relation to diabetes care (Figure 1) to achieve higher rates of NDA attainment and facilitate multifactorial interventions. This includes sections on Diabetes Prevention and Diabetes Remission.

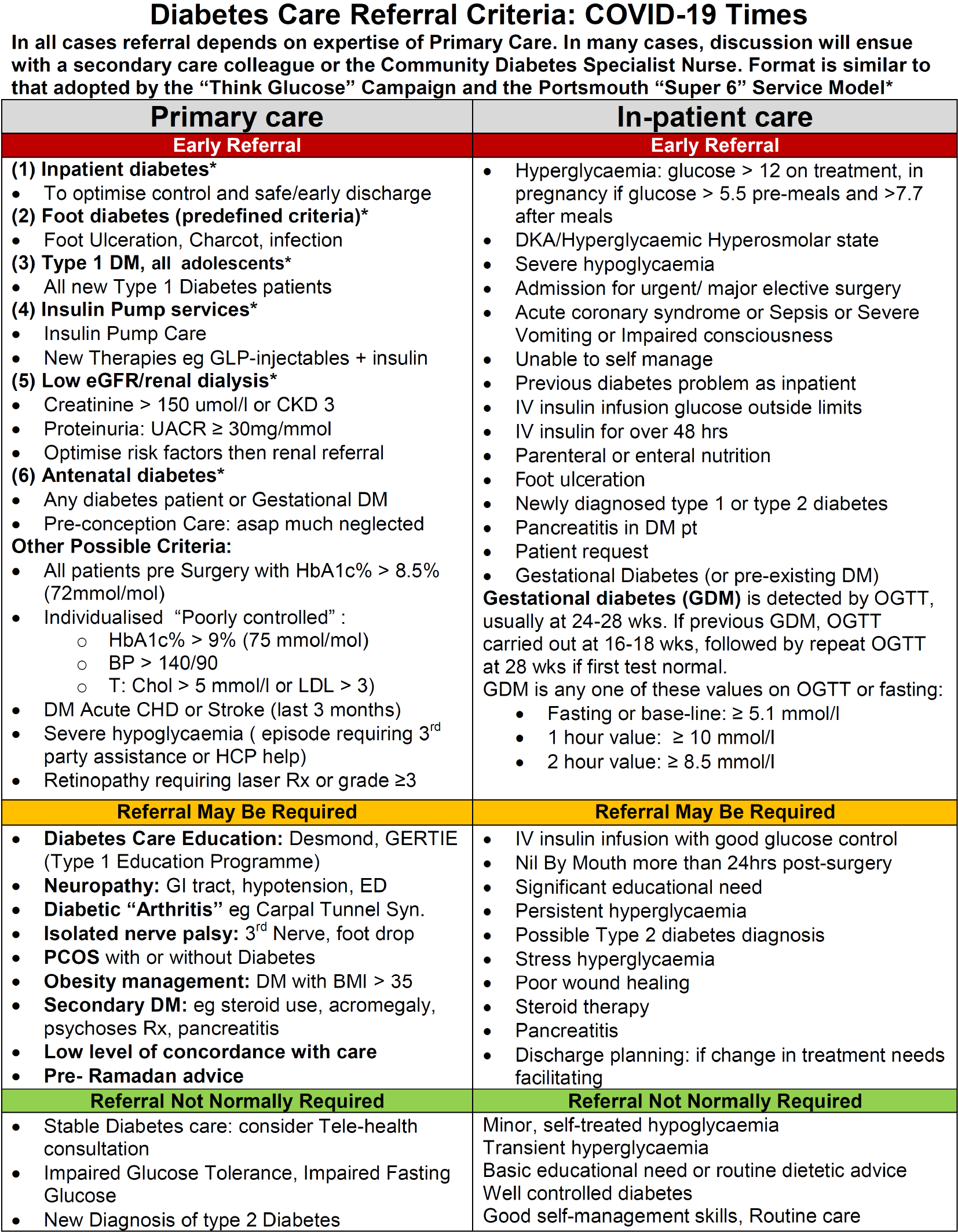

Referral guidelines: Diabetes Expert Advisory group advice has been incorporated on who to refer and who not to refer (Figure 5). Clear guidelines are given by Red Amber Green on whom to refer to the specialist diabetes team from primary care and secondary care. Such advice, if implemented, has the potential to reduce hospital admissions and reduce costly complications such as amputation and end-stage renal disease.

Glucose monitoring advice and choice of meter: This has the potential to save £1.74 million in our region if all Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) merely adopted current practice similar to the best performing CCG. Enhancement on top of this can save £6.3 million per year (NHS England and NHS Improvement-West Midlands). Our region has already saved £ 960000 in 12 mo.

Drug optimisation advice: Data from our region shows that adopting best practice across the region would save £1.65 million on one class of diabetes drugs alone, example dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (NHS England and NHS Improvement-West Midlands modelling data).

Prevention of diabetes advice: There is 86% chance of remission in selected newly diagnosed patients. Data for this comes from the DiRECT Study[15].

Achieving diabetes care excellence through primary care team programme: This is a low cost (£25) basic e-learning platform that covers all the main aspects of diabetes care and care planning using the AS. It is hosted by Coventry University Health Sciences Faculty. It is also incorporated into Sound Doctor’s Diabetes Education Program for patients, which is Quality Institute for Self-Management Education and Training approved.

Improvement in process measures: Implementation of the AS for Diabetes Care resulted in a significant (P < 0.05) improvement including lipid measurement, BP, HbA1c, eye and foot examinations. Using the parameters from NDA, this strategy showed 100% performance of seven of the NICE recommended processes[16]. Our unit scored above average in six out of the seven categories for target care process achievement.

Improvement in outcome measures: The improvement rates (Table 1) were comparable to standards achieved in clinical trial setting specifically researching intensive treatment strategies like Steno-2 and The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study.

Patient and health care professional satisfaction: An audit conducted in 27 countries (44 Diabetes service units) showed that 91% of respondent felt that the strategy would have a positive influence on diabetes care and that it would be practical to implement, even in a non-high income country (Table 2)[13].

In United Kingdom, care planning for all patients with chronic diseases has been proposed as an agreed action plan which is best reflected by the slogan–“no decisions about me without me”[17]. The 15 diabetes healthcare essentials introduced for the diabetes patients not only help in better management outcomes, but also help prevent serious future complications due to the disease[18]. One of the parts of the Year of Care programme for diabetes tested the “house of care” concept, which involves care and support planning at its core surrounded and supported by all the teams, tools and management plans[19]. The AS helps deliver these aspirations. The strategy is also compatible with helping implement other key national guidelines and recent changes in clinical practice[15,20-22].

AS for diabetes care is intended to improve the confidence of the person with diabetes to self-manage their condition with the aspirations and the constraints of the life they lead. We are confident that it has the great potential to reduce the morbidity and mortality due to diabetes in these most difficult of times internationally due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

All our resources are available electronically, gratis, on request. These resources are available to adapt to local clinical practice as HCP and patients see fit.

| 1. | Singh D, Ham C. Improving care for people with long-term conditions: a review of UK and international frameworks. University of Birmingham; NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement; Birmingham: 2006. [Cited August 10, 2020]. Available from: https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-social-sciences/social-policy/HSMC/research/Long-term-conditions.pdf. |

| 2. | Barron E, Bakhai C, Kar P, Weaver A, Bradley D, Ismail H, Knighton P, Holman N, Khunti K, Sattar N, Wareham NJ, Young B, Valabhji J. Associations of type 1 and type 2 diabetes with COVID-19-related mortality in England: a whole-population study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:813-822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 634] [Cited by in RCA: 680] [Article Influence: 113.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Holman N, Knighton P, Kar P, O'Keefe J, Curley M, Weaver A, Barron E, Bakhai C, Khunti K, Wareham NJ, Sattar N, Young B, Valabhji J. Risk factors for COVID-19-related mortality in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in England: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:823-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 620] [Cited by in RCA: 622] [Article Influence: 103.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | National Diabetes Audit. Report 1 Care Processes and Treatment Targets 2018-2019. [Cited January 10, 2021]. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/. |

| 5. | Burt J, Rick J, Blakeman T, Protheroe J, Roland M, Bower P. Care plans and care planning in long-term conditions: a conceptual model. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2014;15:342-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hex N, Bartlett C, Wright D, Taylor M, Varley D. Estimating the current and future costs of Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes in the UK, including direct health costs and indirect societal and productivity costs. Diabet Med. 2012;29:855-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 559] [Cited by in RCA: 582] [Article Influence: 41.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rogers A, Vassilev I, Sanders C, Kirk S, Chew-Graham C, Kennedy A, Protheroe J, Bower P, Blickem C, Reeves D, Kapadia D, Brooks H, Fullwood C, Richardson G. Social networks, work and network-based resources for the management of long-term conditions: a framework and study protocol for developing self-care support. Implement Sci. 2011;6:56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Scott G. Motivational interviewing. 2: How to apply this approach in nursing practice. Nurs Times. 2010;106:21-22. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Rawshani A, Rawshani A, Franzén S, Sattar N, Eliasson B, Svensson AM, Zethelius B, Miftaraj M, McGuire DK, Rosengren A, Gudbjörnsdottir S. Risk Factors, Mortality, and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:633-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 700] [Cited by in RCA: 999] [Article Influence: 124.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gaede P, Lund-Andersen H, Parving HH, Pedersen O. Effect of a multifactorial intervention on mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:580-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2459] [Cited by in RCA: 2385] [Article Influence: 132.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gæde P, Oellgaard J, Carstensen B, Rossing P, Lund-Andersen H, Parving HH, Pedersen O. Years of life gained by multifactorial intervention in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and microalbuminuria: 21 years follow-up on the Steno-2 randomised trial. Diabetologia. 2016;59:2298-2307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 313] [Cited by in RCA: 343] [Article Influence: 34.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, Lipsitz SR, Breizat AH, Dellinger EP, Herbosa T, Joseph S, Kibatala PL, Lapitan MC, Merry AF, Moorthy K, Reznick RK, Taylor B, Gawande AA; Safe Surgery Saves Lives Study Group. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:491-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3703] [Cited by in RCA: 3491] [Article Influence: 205.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lee JD, Saravanan P, Patel V. Alphabet Strategy for diabetes care: A multi-professional, evidence-based, outcome-directed approach to management. World J Diabetes. 2015;6:874-879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Patel V, Morrissey J. The Alphabet Strategy: the ABC of reducing diabetes complications. Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis. 2002;2:58-59. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lean ME, Leslie WS, Barnes AC, Brosnahan N, Thom G, McCombie L, Peters C, Zhyzhneuskaya S, Al-Mrabeh A, Hollingsworth KG, Rodrigues AM, Rehackova L, Adamson AJ, Sniehotta FF, Mathers JC, Ross HM, McIlvenna Y, Stefanetti R, Trenell M, Welsh P, Kean S, Ford I, McConnachie A, Sattar N, Taylor R. Primary care-led weight management for remission of type 2 diabetes (DiRECT): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2018;391:541-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1267] [Cited by in RCA: 1323] [Article Influence: 165.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 16. | National Diabetes Audit. Secondary Care Analysis Profiles, England, 2011-2012. [Cited August 7, 2020]. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publicl/national-diabetes-audit/national-diabetes-audit-2011-12ations/statistica. |

| 17. | Liberating the NHS. London: Department of Health, 2010. [Cited August 7, 2020]. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/216980/Liberating-the-NHS-No-decision-about-me-without-me-Government-response.pdf. |

| 18. | Diabetes UK. Your 15 Diabetes Healthcare Essentials. [Cited July 7, 2020]. Available from: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/managing-your-diabetes/15-healthcare-essentials/what-are-the-15-healthcare-essentials. |

| 19. | Eaton S, Roberts S, Turner B. Delivering person centred care in long term conditions. BMJ. 2015;350:h181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Davies MJ, D'Alessio DA, Fradkin J, Kernan WN, Mathieu C, Mingrone G, Rossing P, Tsapas A, Wexler DJ, Buse JB. Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2018. A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2018;41:2669-2701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2174] [Cited by in RCA: 1904] [Article Influence: 238.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | American Diabetes Association. 10. Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:S125-S150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 332] [Article Influence: 66.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | American Diabetes Association. 6. Glycemic Targets: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:S73-S84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 406] [Cited by in RCA: 590] [Article Influence: 118.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: GMC, No. 7651715.

Specialty type: Endocrinology and metabolism

Country/Territory of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Fatima SS, Wan TT S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH