Published online Aug 15, 2016. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v8.i8.629

Peer-review started: February 24, 2016

First decision: April 15, 2016

Revised: April 26, 2016

Accepted: June 2, 2016

Article in press: June 2, 2016

Published online: August 15, 2016

Processing time: 168 Days and 2.3 Hours

AIM: To measure the compliance of an Academic Hospital staff with a colorectal cancer (CRC) screening program using fecal immunochemical test (FIT).

METHODS: All employees of “Attikon” University General Hospital aged over 50 years were thoroughly informed by a team of physicians and medical students about the study aims and they were invited to undergo CRC screening using two rounds of FIT (DyoniFOB® Combo H, DyonMed SA, Athens, Greece). The tests were provided for free and subjects tested positive were subsequently referred for colonoscopy. One year after completing the two rounds, participants were asked to be re-screened by means of the same test.

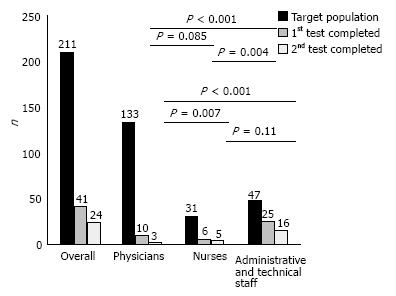

RESULTS: Among our target population consisted of 211 employees, 59 (27.9%) consented to participate, but only 41 (19.4%) and 24 (11.4%) completed the first and the second FIT round, respectively. Female gender was significantly associated with higher initial participation (P = 0.005) and test completion - first and second round - (P = 0.004 and P = 0.05) rates, respectively. Phy

sician’s (13.5% vs 70.2%, P < 0.0001) participation and test completion rates (7.5% vs 57.6%, P < 0.0001 for the first and 2.3% vs 34%, P < 0.0001 for the second round) were significantly lower compared to those of the administrative/technical staff. Similarly, nurses participated (25.8% vs 70.2%, P = 0.0002) and completed the first test round (19.3% vs 57.6%, P = 0.004) in a significant lower rate than the administrative/technical staff. One test proved false positive. No participant repeated the test one year later.

CONCLUSION: Despite the well-organized, guided and supervised provision of the service, the compliance of the Academic Hospital personnel with a FIT-based CRC screening program was suboptimal, especially among physicians.

Core tip: The fecal immunochemical test (FIT) for hemoglobin represents an attractive alternative to colonoscopy for population colorectal cancer (CRC) screening programs, since it combines high diagnostic effectiveness and wide acceptance, probably in relation to its non-invasive nature. Accordingly, we assessed the compliance of the staff of an Academic Hospital with a CRC screening program by means of FIT. Despite the well-organized, guided and supervised provision of the service, our results indicated very low overall uptake rate of the test and, interestingly, significantly less compliance of physicians and nurses as compared to the rest Hospital personnel.

- Citation: Vlachonikolou G, Gkolfakis P, Sioulas AD, Papanikolaou IS, Melissaratou A, Moustafa GA, Xanthopoulou E, Tsilimidos G, Tsironi I, Filippidis P, Malli C, Dimitriadis GD, Triantafyllou K. Academic hospital staff compliance with a fecal immunochemical test-based colorectal cancer screening program. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2016; 8(8): 629-634

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v8/i8/629.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v8.i8.629

Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening using colonoscopy in average-risk adults aged more than 50 years (or in younger subjects with a family history of CRC) decreases the incidence and mortality rates for CRC through detection and removal of premalignant lesions[1]. Given that the compliance of the general population in colonoscopy screening programs is low, other screening modalities have been implemented as well[2]. The high diagnostic performance of the fecal immunochemical test (FIT) as compared to other CRC screening tests combined with its superior acceptability as a non-invasive screening measure[3,4] result in being widely recommended for CRC screening. In addition, a positive FIT-test could represent a stronger motivation for patients to participate in colonoscopy-based CRC screening programs. However, there are no studies to confirm or reject the latter assumption, especially among health care providers.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the compliance of the staff of an Academic Hospital with a CRC screening program using FIT.

During an initiation event at the Conference Auditorium of our Hospital, expert Gastroenterologists of the Hepatogastroenterology Unit of the Second Department of Internal Medicine and Research Institute, Medical School, Athens University presented the study aims and outlines to “Attikon” University General Hospital employees. Employees aged 50 years or older were identified through the Human Resources Department of the Hospital. They were thoroughly informed by a team of physicians and medical students and they were invited to be screened for CRC by means of two rounds of FIT (DyoniFOB® Combo H, DyonMed SA, Athens, Greece).

Candidates received directly as well as by mail a letter explaining the rationale of the program, an informed consent form to sign before the procedure and a questionnaire that covered demographic data of the participants and family history for CRC or colonic polyps. In addition, a FIT kit was provided for free with instructions for collecting the stool sample and returning the kit for processing at the Hepatogastroenterology Unit of our Hospital. Upon the return of the first kit, participants were requested to repeat the procedure with a second kit. Participants were informed on their results and those who tested positive were offered colonoscopy. One year after completing the two rounds, all participants were contacted by telephone in order to be reminded of the need to repeat screening.

The study outcome was to evaluate the compliance of the Hospital personnel with a FIT-based screening program by measuring the personnel participation rates.

The study protocol and the participants’ informed consent form had been approved by the Attikon University General Hospital Ethics Committee.

Categorical variables presented as value (%) were analyzed using a χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test with the Yates correction, as needed. P value < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

The statistical methods used in the present study were reviewed by Professor Konstantinos Triantafyllou, Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University, Athens, Greece who has been trained in biostatistics.

The study was carried out from September 2013 to March 2015.

The target population - 116 males and 95 females - consisted of 133 physicians, 31 nurses and 47 administrative and technical staff members.

Fifty-nine (27.9%) employees agreed to participate and signed the informed consent form; 23 (19.8%) males vs 36 (37.9%) females (P = 0.005). All of them were asymptomatic, none had family history of CRC but 14 had a family history of colonic polyps. Participants as well as non-participants baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1.

| Characteristics | Participants n (%) | Non-participants n (%) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 23 (39) | 93 (61) |

| Female | 36 (61) | 59 (39) |

| Employee status | ||

| Physicians | 18 (30) | 115 (76) |

| Nurses | 8 (14) | 23 (15) |

| Administrative and technical staff | 33 (56) | 14 (9) |

| Educational level | ||

| High | 20 (34) | |

| Intermediate | 20 (34) | |

| Basic | 19 (32) | |

| Family history of colonic polyps | ||

| Yes | 14 (24) | |

| No | 45 (76) |

Physicians showed significantly lower willingness to participate (18 of 133 or 13.5%) in comparison to the administrative and technical staff group (33 of 47 or 70.2%, P < 0.0001) and the nurses group (8 of 31 or 25.8%, P = 0.03).

Among the participants, only 41 returned the first kit for evaluation indicating an overall completion rate of 19.4%; 15% and 54% of the participants with and without a family history of colonic polyps, respectively (P = 0.74). The first FIT round was completed by significantly more female in comparison to male participants (27 of 95 or 28.4% vs 14 of 116 or 12.1%, P = 0.004).

As shown in Figure 1, there was higher test completion rate in the administrative and technical staff group (57.6%) in comparison to the physicians’ and nurses groups (7.5% and 19.3%; P < 0.0001 and P = 0.004, respectively).

The overall completion rate for the second FIT test was 11.4% (Figure 1). Only 24 of the 40 employees who received the second test kit returned it for evaluation; 5% with family history of colonic polyps and 34% without (P = 0.06).

Similarly to the first round, significantly more female participants completed both first and second FIT rounds in comparison to male participants (16 of 95 or 16.8% vs 8 of 116 or 6.8%, P = 0.05).

Figure 1 shows that the physicians’ group second FIT round completion rate (2.3%) was the lowest in comparison to the nurses and the administrative/technical staff groups (16.1% and 34%; P = 0.007 and P < 0.0001, respectively). No difference (P = 0.11) was detected between nurses and administrative/technical staff groups in second FIT round completion rates.

Out of the 65 performed FIT examinations, a single test was proved false positive based on the colonoscopy that followed. One year later, we informed by telephone the 41 study participants who completed at least the first FIT round for the need to repeat screening. Twenty-two of them denied further screening since they believed that the negative results of their past tests would last forever, while 18 were willing to undergo screening annually. Only one of the participants accepted to be screened, but even this subject did not finally proceed to being tested.

A fundamental aspect of all screening programs and a prerequisite for their success is participation and compliance of the target population. Even though several tests for CRC screening exist, their participation rates remain suboptimal[5,6]. Population screening programs include endoscopic procedures (i.e., colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy or colon video capsule endoscopy), radiologic tests, including barium enema and computed tomography-colonography and fecal tests, such as the fecal occult blood test (FOBT) and FIT. FIT, being a non-invasive screening test could serve as an attractive alternative to colonoscopy for CRC screening, since it combines effectiveness and wide acceptance, probably due to its non-invasive nature. This has resulted in its widespread adoption in countries with organized CRC screening programs[3,7]. Recently, a CRC screening program using biannual FIT that was conducted in Italy revealed not only a reduction by 30% in CRC mortality of the general population but also a 10% decrease in CRC incidence after 8 years of study[8].

In the present study we evaluated for the first time, the compliance of the staff of an Academic Hospital to a non-invasive CRC screening program, using FIT. We proceeded with two rounds of FIT testing in order to obtain better test sensitivity without compromising overall test uptake, based on the results of a study that showed that the participation rate was similar when completing one or two samples of the FIT test[9].

Three randomized trials have indicated a participation rate for FIT approximately 60%, higher than that of the gFOBT[9-11], while the reported overall participation rate in the FIT studies ranges widely from 17%-77%[8-12].

Our results showed that: (1) the overall uptake of the FIT was within the lower reported rates worldwide, even in subjects with positive family history for colonic polyps; (2) significantly less physicians and nurses completed the FIT screening program compared to the hospital administrative and technical personnel; (3) female individuals showed both a higher willingness to participate and a higher participation rate after the two FIT rounds; and (4) participants were reluctant to continue screening annually.

The screening completion rate of our population was deemed lower - 19.4% for the first and 11.4% for the second round, respectively - than expected for a well organized, controlled and supervised in the participants’ occupational environment program. As shown in Figure 1 the low overall screening completion rate is a consequence of physicians - mainly - and nurses’ low completion rates. These disappointing rates, reaching the lowest 2.25% among physicians for the second test round, may indicate a major study limitation. Issues like embarrassment and discomfort may have eventually influenced the compliance of the medical and nursing staff, since there was an interaction between the providers of the screening test and the participants in the same practice. Low participation rates among hospital employees were shown during a CRC screening program that consisted of a questionnaire, followed by an endoscopic procedure among the personnel of an Academic Medical Center in Israel. The program yielded similar results to ours, as merely 24.7% of the staff that was invited to participate completed the questionnaire; 16.2% of them agreed to be further tested[13].

Providing the tests by dedicated unrelated to the participants services, e.g., committees organized by the Ministry of Health, although more complex, time consuming and expensive, could eventually, overcome this obstacle.

On the other hand, in a cancer screening program for cervical, breast, colorectal and prostate cancers in health care workers in Italy, the participation rate was higher than that of the general population with an overall compliance of 83.8%[14]. Moreover, it has been suggested that compliance to other cancer screening programs, such as screening for prostate cancer in men and breast cancer in women has been positively associated with compliance to CRC screening[15]. Therefore, regional and site specific issues may also be important for CRC screening program successful implementation.

Several additional factors influence CRC-screening uptake; awareness for CRC, different screening modalities - invasive and non-invasive - as well as the way in which the latter are offered to the population. Interestingly, almost half of our screening subjects who completed at least the first test round denied further screening due to ignorance for repeating CRC screening annually. Similarly, in a recent study among Greek medical students it was shown that there is lack of information about CRC screening[16]. Awareness of the risk factors for CRC, signs and symptoms as well as the prognosis of the disease are all factors that can increase screening uptake[17,18]. European studies have reported low awareness about CRC compared to other cancers such as lung cancer and prostate in men and breast cancer in women[19].

Low educational level has been associated with low participation rates in CRC screening programs[17], whereas it has also been demonstrated that there is a positive association between low socio-economic status with low screening compliance rates[20]. Interestingly, the majority (55%) of employees who initially consent to be screened were at the intermediate of basic educational level (four nurses and 28 administrative/technical staff members) compared to those with high educational level (18 physicians, 4 nurses and 5 administrative/technical staff members). This discordance with the existing literature could, at least partially, be explained by the small number of participants and the aforementioned issues of embarrassment and discomfort.

In a recent investigation regarding screening programs for breast and cervical cancers at a University Hospital in Turkey among female health care personnel, it was concluded that female physicians and nurses don’t pay the adequate attention to these screening programs[21]. Nevertheless, in our study the completion rate of both FIT rounds was higher among the female compared to that of the male hospital stuff (16.8% vs 6.8%).

Our study is limited by the small, very selected (employees of an academic health care provision) sample, which is not representative of the general population, and our results might not be directly extrapolated to other medical facilities worldwide. Another study caveat is the limited test candidate’s baseline information provided by the Human Resources Department of the Hospital that precluded the identification of predictors of participation in the program beyond that of female gender. Finally, we acknowledge as limitations of our study the fact that no data was captured regarding possible participants’ CRC screening in the past or current bowel symptoms. Identification of the reasons for non-compliance would have also been of great interest, although not available in the present study.

In conclusion, the compliance of the Attikon University General Hospital personnel with a FIT-based CRC screening program was suboptimal, especially among physicians, despite the well-organized, guided and supervised provision of the service.

DyonMed SA, Athens, Greece kindly provided the fecal immunochemical test (DyoniFOB® ComboH) for the study purposes.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening by means of colonoscopy decreases the incidence and mortality rates for CRC through early detection and removal of premalignant lesions. Fecal immunochemical test (FIT) is also implemented as a CRC screening modality and has the advantage of being a non-invasive tool. The authors aimed to assess the compliance of an Academic Hospital staff with a CRC screening program using FIT.

According to the results, the compliance of the Academic Hospital personnel with a FIT-based CRC screening program was suboptimal, especially among physicians.

Although it is established that low educational level is associated with low participation rates in CRC screening programs, the results of this study indicate that those with high educational level exhibited less compliance as compared to those of low-intermediate one.

The results of the present study may enhance the efforts for better population awareness regarding CRC screening.

The FIT is a non-invasive test that detects human hemoglobin in stool and represents an efficacious means of CRC screening. Compliance refers to the individual’s adherence to a recommended diagnostic or therapeutic procedure.

It is an interesting manuscript on important topic. The paper is well-written.

| 1. | Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18694] [Cited by in RCA: 21466] [Article Influence: 1951.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 2. | Gaglia A, Papanikolaou IS, Veltzke-Schlieker W. New endoscopy devices to improve population adherence to colorectal cancer prevention programs. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;2:244-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Allison JE, Fraser CG, Halloran SP, Young GP. Population screening for colorectal cancer means getting FIT: the past, present, and future of colorectal cancer screening using the fecal immunochemical test for hemoglobin (FIT). Gut Liver. 2014;8:117-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Quintero E, Castells A, Bujanda L, Cubiella J, Salas D, Lanas Á, Andreu M, Carballo F, Morillas JD, Hernández C, Jover R, Montalvo I, Arenas J, Laredo E, Hernández V, Iglesias F, Cid E, Zubizarreta R, Sala T, Ponce M, Andrés M, Teruel G, Peris A, Roncales MP, Polo-Tomás M, Bessa X, Ferrer-Armengou O, Grau J, Serradesanferm A, Ono A, Cruzado J, Pérez-Riquelme F, Alonso-Abreu I, de la Vega-Prieto M, Reyes-Melian JM, Cacho G, Díaz-Tasende J, Herreros-de-Tejada A, Poves C, Santander C, González-Navarro A. Colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical testing in colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:697-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 703] [Cited by in RCA: 675] [Article Influence: 48.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Smith RA, Brooks D, Andrews KS, Dash C, Giardiello FM, Glick S, Levin TR. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:130-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1125] [Cited by in RCA: 1209] [Article Influence: 67.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sharp L, Tilson L, Whyte S, O’Ceilleachair A, Walsh C, Usher C, Tappenden P, Chilcott J, Staines A, Barry M. Cost-effectiveness of population-based screening for colorectal cancer: a comparison of guaiac-based faecal occult blood testing, faecal immunochemical testing and flexible sigmoidoscopy. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:805-816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Halloran SP, Launoy G, Zappa M. European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis. First Edition--Faecal occult blood testing. Endoscopy. 2012;44 Suppl 3:SE65-SE87. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Giorgi Rossi P, Vicentini M, Sacchettini C, Di Felice E, Caroli S, Ferrari F, Mangone L, Pezzarossi A, Roncaglia F, Campari C. Impact of Screening Program on Incidence of Colorectal Cancer: A Cohort Study in Italy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1359-1366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | van Rossum LG, van Rijn AF, Laheij RJ, van Oijen MG, Fockens P, van Krieken HH, Verbeek AL, Jansen JB, Dekker E. Random comparison of guaiac and immunochemical fecal occult blood tests for colorectal cancer in a screening population. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:82-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 511] [Cited by in RCA: 526] [Article Influence: 29.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hoffman RM, Steel S, Yee EF, Massie L, Schrader RM, Murata GH. Colorectal cancer screening adherence is higher with fecal immunochemical tests than guaiac-based fecal occult blood tests: a randomized, controlled trial. Prev Med. 2010;50:297-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hol L, van Leerdam ME, van Ballegooijen M, van Vuuren AJ, van Dekken H, Reijerink JC, van der Togt AC, Habbema JD, Kuipers EJ. Screening for colorectal cancer: randomised trial comparing guaiac-based and immunochemical faecal occult blood testing and flexible sigmoidoscopy. Gut. 2010;59:62-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 345] [Cited by in RCA: 369] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Schreuders EH, Ruco A, Rabeneck L, Schoen RE, Sung JJ, Young GP, Kuipers EJ. Colorectal cancer screening: a global overview of existing programmes. Gut. 2015;64:1637-1649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 674] [Cited by in RCA: 959] [Article Influence: 87.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Levi Z, Chorev N, Segal N, Plaut S, Shemesh I, Chadad B, Murad I, Niv G, Niv Y. Screening for colorectal cancer in personnel of an academic medical center. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2301-2304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pisati G, Cerri S, Marinelli M, Tedeschi B, Valsecchi E. [Cancer screening programme in health care workers]. G Ital Med Lav Ergon. 2011;33:57-60. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Carlos RC, Fendrick AM, Ellis J, Bernstein SJ. Can breast and cervical cancer screening visits be used to enhance colorectal cancer screening? J Am Coll Radiol. 2004;1:769-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Papanikolaou IS, Sioulas AD, Kalimeris S, Papatheodosiou P, Karabinis I, Agelopoulou O, Beintaris I, Polymeros D, Dimitriadis G, Triantafyllou K. Awareness and attitudes of Greek medical students on colorectal cancer screening. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4:513-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gimeno García AZ. Factors influencing colorectal cancer screening participation. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:483417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gimeno Garcia AZ, Hernandez Alvarez Buylla N, Nicolas-Perez D, Quintero E. Public awareness of colorectal cancer screening: knowledge, attitudes, and interventions for increasing screening uptake. ISRN Oncol. 2014;2014:425787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Manning AT, Waldron R, Barry K. Poor awareness of colorectal cancer symptoms; a preventable cause of emergency and late stage presentation. Ir J Med Sci. 2006;175:55-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | James TM, Greiner KA, Ellerbeck EF, Feng C, Ahluwalia JS. Disparities in colorectal cancer screening: a guideline-based analysis of adherence. Ethn Dis. 2006;16:228-233. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Kabacaoglu M, Oral B, Balci E, Gunay O. Breast and Cervical Cancer Related Practices of Female Doctors and Nurses Working at a University Hospital in Turkey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:5869-5873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Greece

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Hallgren T, Hammerman A, Sperti C S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ