INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is ranked the sixth most common tumor type worldwide, and because of its very poor prognosis, is the third most common cause of cancer death with an annual mortality of 600 000 patients[1]. Before the development of sorafenib, effective standard chemotherapy was unavailable. Sorafenib has anti-proliferative, anti-angiogenic, and anti-apoptotic effects by inhibiting multiple kinases such as RAF kinase, and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR)-1, VEGFR-2, and VEGFR-3[2]. We previously reported that suppression of VEGF and VEGFR signaling significantly suppressed HCC growth in the animal model[3]. Accordingly, it has been shown that sorafenib significantly improved the overall survival in patients with advanced HCC in Western countries in the SHARP trial[4]. Furthermore, an Asia-Pacific trial has shown that it was also effective in the region[5]. Sorafenib is now recognized in many countries as one of the standard therapies for advanced HCC, and consequently medical treatment has changed dramatically. However, so far many types of diverse side effects have been reported, such as hand-foot skin reaction, gastrointestinal bleeding and arterial thromboembolism. Furthermore, additional unexpected effects include spleen infarction, acute pancreatitis and thyroiditis, which are rare in conventional chemotherapy[6-8]. To our knowledge, there is no report linking a case of acute cholecystitis with sorafenib treatment. Here, we report a case of acute acalculous cholecystitis along with a marked eosinophilia in an advanced HCC patient during the course of treatment with sorafenib.

CASE REPORT

A 43-year-old woman with hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related liver cirrhosis was admitted to our hospital to treat the advanced HCC. She had previously received transcatheter hepatic arterial chemoembolization (TACE) 3 times, and recently 2 cycles of hepatic artery infusion (HAI) chemotherapy to treat the multiple HCC. However, the presence of several new lesions within a few months after the treatment led to categorize the case as a progressive disease in agreement with RECIST criteria (Figure 1A). She was in a good state of health (ECOG PS 0) before the treatment. The absence of encephalopathy and ascites, and the normality of coagulation parameters (PT-INR 1.12) of bilirubin (0.7 mg/mL), and albumin (3.9 g/dL) led to classifying the patient into functional class Child-Pugh A. Blood chemistry tests showed a mild elevation of α-fetoprotein values (33.2 ng/mL), and a slight increase of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (61 IU/L) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (49 IU/L). Treatment with sorafenib at 800 mg/d was started from the next admission. Although she showed several diverse effects such as diarrhea and hand-foot-skin reaction, which met the criteria of grade 1-2 of Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Event v3.0 (CTCAE), these symptoms were manageable and did not interfere with the patient’s daily activities. At 27th day of sorafenib therapy, the patient complained of a sudden onset of severe right hypocondrial pain with rebound tenderness and muscle defense. Laboratory examination revealed mild elevation of transaminases (AST: 134 IU/L, ALT: 118 IU/L), biliary enzymes (γGTP: 78 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase: 503 IU/L), bilirubin (1.4 mg/ml), inflammation markers (WBC: 10 500/μL, CRP: 2.3 mg/dL) and a marked eosinophilia (eosinocyte 32.3%). Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed a swollen gallbladder with exudate associated with severe inflammation without stones or debris (Figure 1B). Unfortunately, in this case no other diagnostic image such as MRCP, was performed at the same time. Sorafenib was immediately stopped, and steroid-pulse therapy was performed. Prednisolone (500 mg/d) for 3 d drastically improved all clinical manifestations along with normalization of CT findings, eosinophilia, and liver functions. Five days after treatment, the gallbladder swelling was markedly improved with reduced ascites exudate (Figure 1C). The patient was discharged from hospital 2-wk after treatment.

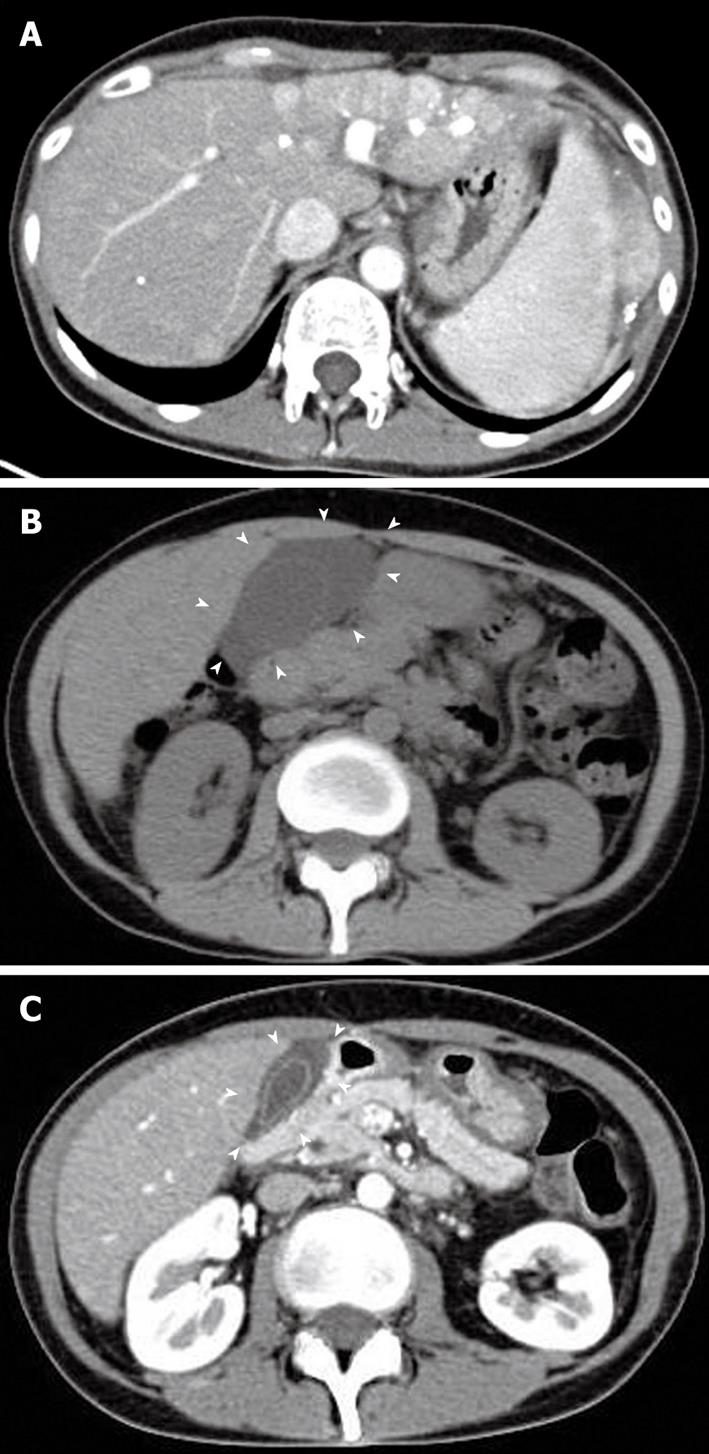

Figure 1 Abdominal computed tomography scan of the patient.

A: Enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showing the diffuse HCC which occupied whole left lobe and several new lesions within diameter 1 cm in right liver before the treatment with sorafenib. Triangle indicates the HCC lesion; B: Abdominal CT scan at the onset of acute cholecystitis during the treatment with sorafenib. The CT revealed the gallbladder swelling with exudate associated with severe inflammation without stones or debris (arrowheads); C: Follow-up abdominal CT scan at 5 d after treatment of acute cholecystitis. Gallbladder swelling was markedly improved with reduced ascites exudate (arrowheads).

DISCUSSION

In this report, we describe a patient who developed acute acalculous cholecystitis during the course of sorafenib treatment along with a marked eosinophilia in an advanced HCC. The most common adverse effects of sorafenib consist of fatigue, as well as gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea and diarrhea, anorexia, weight loss, and skin toxicity such as hand-foot syndrome[4]. Most of these effects are tolerable, and we can manage these clinical symptoms since we have experienced them with conventional chemotherapeutic agents. However, unexpected sorafenib toxicities have also been reported including thrombotic events and splenic infarction[6]. To date, there is no report describing acute acalculous cholecystitis during the course of sorafenib treatment. The exact mechanism of this effect is unclear at this time. However, we postulate that eosinophilic cholecystitis could occur due to a marked peripheral blood eosinophilia. Eosinophilic cholecystitis is an infrequent form of cholecystitis[9,10]. In clinical practice, eosinophilic cholecystitis is usually unsuspected and is clinically indistinguishable from the predominant form of calculous cholecystitis[10,11]. Although the etiology of eosinophilic cholecystitis is still uncertain, the proposed causes include parasites, gallstones, and allergic hypersensitivity response to drugs such as phenytoin, erythromycin, cephalosporin, and herbal medications[12,13]. The condition sometimes shows a marked peripheral blood eosinophilia. Eosinophilic cholecystitis may develop with several diseases, such as eosinophilic gastroenteritis, eosinophilic pancreatitis, and idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome[14-16]. Unlike eosinophilic gastritis, most patients with eosinophilic cholecystitis have no history of allergy, similar to our case[17]. Peripheral hypereosinophilia is not a constant finding either, although the characteristic histologic feature of eosinophilic cholecystitis is transmural inflammatory infiltration of the gallbladder wall that is composed of more than 90% eosinophils[10]. In the current case, we did not have any histological evidence of eosinophilic cholecystitis since the patient did not undergo cholecystectomy. This is the main negative point of the final diagnosis of eosinophilic cholecystitis in our case. However, the patient exhibited a marked peripheral eosinophilia along with confirmation of acute cholecystitis by several imaging modalities such as CT. It has been reported that a marked peripheral eosinophilia mostly correlates with eosinophilic infiltration in the gallbladder wall, indicating that, at least, there was some infiltration of eosinophils in the gallbladder. Medical management of eosinophilic cholecystitis may depend on the severity and disease location. Considerable infiltration of the muscularis by eosinophils with vascular occlusion entails surgery, whereas involvement of the mucosa or adventitia without vascular changes responds well to steroids[18]. In this case, after termination of sorafenib and treatment with steroid, eosinophilia and all clinical manifestations drastically improved along with normalization of the imaging features.

Another possibility is the ischemic change of the gallbladder by sorafenib since ischemic heart disease has been reported in the SHARP trial[4]. It has been reported that gallbladder ischemia sometimes occurred after the treatment with TACE, especially along with embolization of the gallbladder artery[19]. However, we postulate that this was not the case in our patient. We performed selective TACE and HAI for the respective tumor lesion, and we did not inject the gelform and chemotherapeutic agent into a cholecystic artery in this patient. Furthermore the clinical course of this patient was not typical of manifestations of ischemic cholecystitis. In future, further examination of this type of patient is required to elucidate the exact mechanisms.

In conclusion, we report a rare case of acute cholecystitis along with a marked eosinophilia in a patient with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma during the course of sorafenib treatment. Since this compound can induce multiple adverse effects, which are uncommon using conventional chemotherapeutic agents, physicians should be aware and consider the possibility of clinical manifestations of acute cholecystitis when using sorafenib.