CASE REPORT

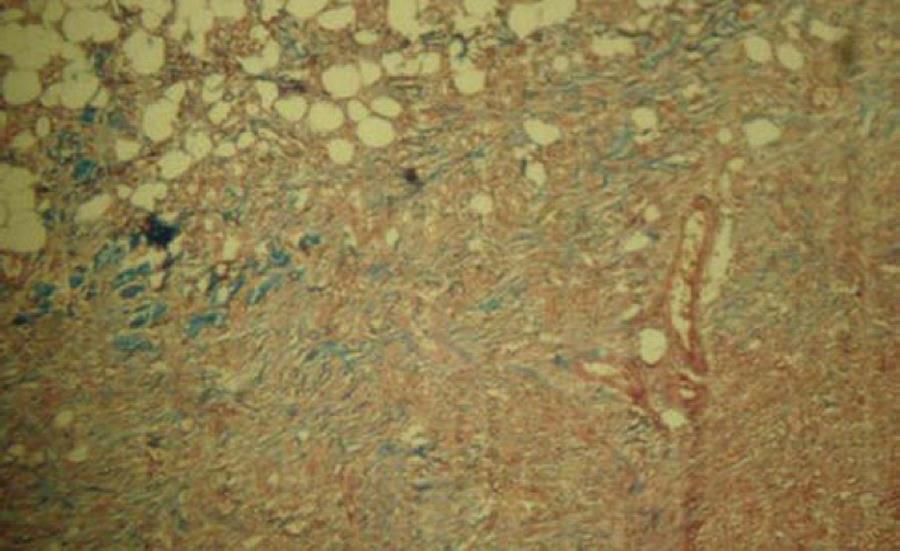

A 27-year-old male patient presented at the emergency department complaining of a 6-wk history of recurrent cramping abdominal pain. He had previously been admitted at three hospitals. Increased abdominal pain, nausea and seven episodes of vomiting occurred during the 24 h prior to admission at our institution. Physical examination revealed signs of dehydration, a temperature of 36.8°C, a pulse of 94 beats per minute, a respiratory rate of 18 per minute and blood pressure 100/60 mmHg. Bowel sounds were hyperactive, his abdomen was distended, with tenderness, but no guarding or rebound. White blood cell count was 8090 per cubic millimeter, with 76% neutrophils. Other tests were unremarkable. Plain abdominal film showed dilated bowel loops and air-fluid levels (Figure 1). At the second day after admission, after fluid resuscitation, the patient recovered transit of feces and gases, and vital signs normalized; white blood cell count was 6400 per cubic millimeter, with 80% neutrophils. Transabdominal ultrasound, gave images suggestive of an intussusception (Figure 2A and B). On an elective basis, the patient underwent a laparotomy. Dilated jejunum and ileum proximal to an intussusception which was 30 cm proximal to the ileocecal valve were found (Figure 3A). Resection and anastomosis were performed around the intussusception, whose lead point was a 3 cm pedunculated-type polypoid tumor (Figure 3B). No other palpable tumor was found during exploration of the bowel. Histopathology revealed a solid mass with vascular congestion and superficial necrosis, formed by well-differentiated adult-type adipose cells, separated by fibrous tissue, fibrocytes, fibroblasts and mesenchymal cells, which showed no pleomorphic or mitotic features, although irregular vessel distribution was observed. These findings are compatible with the diagnosis of an ileal hamartoma (Figure 4). After an uneventful recovery, the patient was discharged on the fifth postoperative day. After 18 mo, the patient is in good health.

Figure 1 Plain abdominal film showed dilated bowel loops and air-fluid levels.

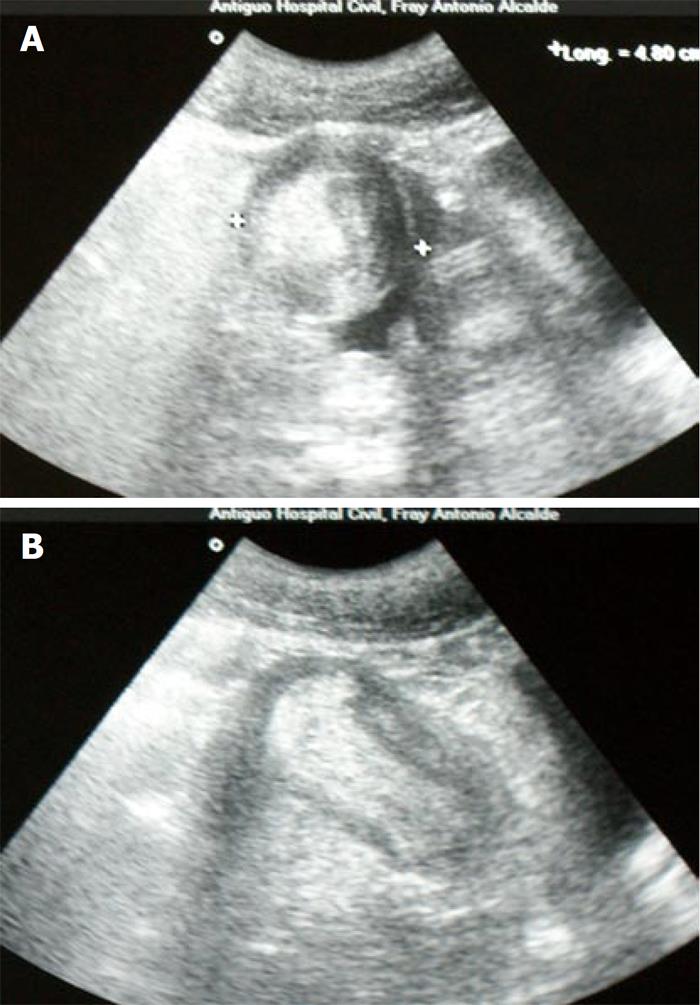

Figure 2 Ultrasonographic feature of a “target” sign on a transverse view (A), and a “sausage-shaped image” in a longitudinal view (B).

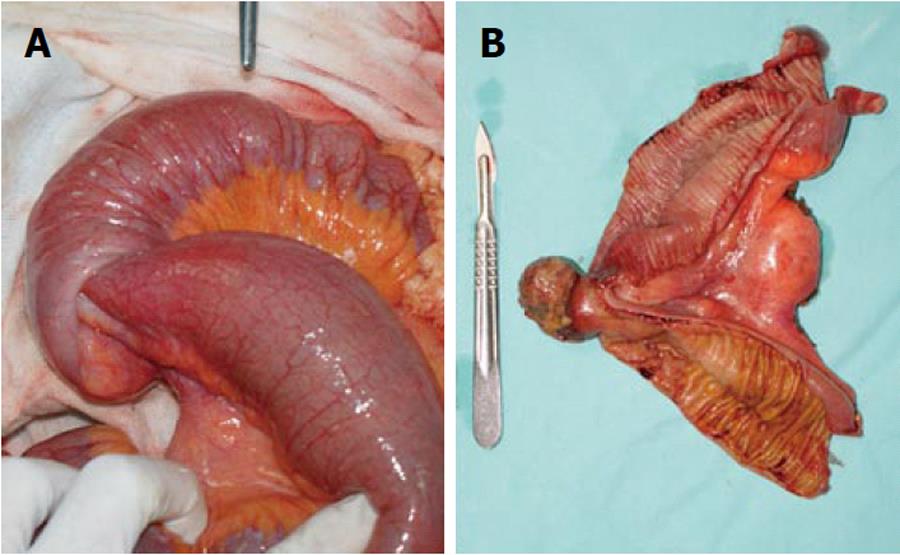

Figure 3 Distended bowel proximal to the intussusception (A), open surgical specimen showing a 3 cm pedunculated-type polypoid tumor (B).

Figure 4 Histopathologic appearance of the ileal tumor showing an active mesenchymal lesion, with no malignant transformation (Masson’s trichrome stain, × 10).

DISCUSSION

Intussusception refers to the telescoping displacement of a proximal segment of bowel (intussusceptum) into the lumen of the adjacent distal segment (intussuscipiens). It accounts for 1%-5% of all cases of intestinal obstruction in adults[1]. In contrast to children, in whom 95% of intussusceptions take place, an etiology is found in 70%-90% of adult patients[2]. However, preoperative diagnosis in adult cases is infrequent, due to its varying presentation, which most often is consistent with intestinal obstruction, but may manifest with acute, intermittent or chronic symptoms[2,3]. In up to 90% of adult cases, a well defined lesion serves as a lead point for the adjacent bowel segment to telescope into the lumen of the distal segment, causing mesentery compromise. The bowel edema and subsequent compression of vessels in the mesentery may cause ischemic necrosis of the bowel wall[4]. Clinical presentation of intussusception is nonspecific. The predominant symptoms are those of partial intestinal obstruction, where the most important characteristic of abdominal pain is its periodic, intermittent and cramping nature[2,4,5]. Other signs and symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, constipation, fever, intestinal bleeding, diarrhea, and a palpable abdominal mass are less frequent. Although there are acute presentations, the mean duration of symptoms exceeds 7 d, while clinical manifestations have been present from two weeks to several months in most of the cases, sometimes reaching one to five years[1,2,4-9].

A correct preoperative diagnosis ranging from 30% to 70% has been reported, mainly due to the varying and nonspecific clinical presentation[1,2,4-7,9]. Since obstructive symptoms predominate in most cases, plain abdominal films are the first diagnostic modality. Signs of intestinal obstruction such as dilated loops and air fluid level may be seen, and information about the site of obstruction may be obtained[1,4,7-10]. An upper gastrointestinal series may reveal a small bowel intussusception; a proximal dilated bowel and a beaklike change in the caliber at the obstruction. The classic “stacked coin” or “coiled spring” signs are characteristic in upper gastrointestinal series[1,2,4,5,10,11]. Ultrasonography is a useful diagnostic modality; the classic imaging features are the “target” or “doughnut” signs in the transverse view and the “pseudo-kidney” sign in the longitudinal view. However, obesity, the presence of air in the distended bowel loops and operator skill may limit the study accuracy[9,10,12]. Abdominal Computed Tomography scan is considered the most useful imaging modality, with a diagnostic accuracy of 58% to 100%. It is particularly useful when a mass is found on physical examination. The characteristic features correspond to an early target mass with enveloped, eccentrically located areas of low density, which may appear as “target sign”, “sausage shaped mass” or “reniform mass”. A CT scan may define the location, nature of the mass, its relationship to surrounding tissues, and staging in the case of suspected malignancy[1,2,8,10].

In adult intussusception, surgical exploration remains essential. Nevertheless, controversy persists concerning the optimal surgical management strategy. The principle of resection without reduction is well established[11]. Several considerations have been highlighted: the frequency of an underlying etiology, the prevalence of associated malignancy, the anatomic site and extent of intussusception, and the degree of inflammation and ischemia in the affected bowel segment[5]. The high likelihood of malignancy in colonic intussusception justifies resection without reduction. In small bowel intussusception, a more selective approach seems feasible, although resection is advocated unless a benign lesion has been previously confirmed. Nevertheless, in the majority of cases, the inability to differentiate benign from malignant etiologies, signs of bowel ischemia and the possibility of perforation should be considered[1,4,6]. The overall incidence of malignancy in adult intussusception lesions is approximately 40%; an overall malignancy incidence of up to 40% in small bowel intussusception has been reported, whereas in colonic intussusception it has been as high as 65%[1,2,4,5,10,11].

In 1940, Clarke used the term “Myoepithelial hamartoma” to describe gastrointestinal submucosal tumors comprising glandular elements, lined by epithelial cells and smooth muscle[13]. The predominant tissue in these tumors may be either connective tissue derivatives such as lamina propia, smooth muscle, vasoformative tissue, or nerve elements, or epithelial elements[14]. Only a few cases of intussusception secondary to a solitary hamartoma have been reported, most of them in the pediatric population[15-22]. In adult patients, reported cases are also scarce, both among series and in case reports[1,4,23-27].

In the adult patient herein reported, a 6-wk history of recurrent cramping abdominal pain, requiring three previous hospital admissions, as well as the increased pain, nausea and vomits that occurred during the 24 h, were consistent with intermittent intestinal obstruction. Dilated intestinal loops with air-fluid levels seen on the plain abdominal film were accordingly indicative. The classic ultrasound findings were consistent with an intussusception as the cause of the intestinal obstruction, making the CT scan non- essential. The apparent transient resolution manifested by the regaining of transit of gas and feces allowed a non-urgent laparotomy. Reduction was avoided for reasons already described, and resection of an intestinal segment proximal and distal to the intussusception was performed.

In conclusion, we have reported an unusual cause of obstruction in an adult patient, secondary to a hamartoma as the lead point of an ileal intussusception.