INTRODUCTION

Lipoma of the colon is a rare condition which may be detected incidentally at colonoscopy, surgery or autopsy[1]. Most colonic lipomas occur in the cecum and ascending colon, and are asymptomatic and need no treatment. However, if the lesion exceeds 2 cm in diameter, it may produce symptoms, such as abdominal pain, bleeding, obstruction, intussusception, and even weight loss[2-6]. Large colonic lipomas, can sometimes be mistaken for malignancy, which may result in extensive surgical operations[7]. We report a large broad-based ulcerated cecal lipoma (6.0 cm in greatest dimension) in a 68-year-old woman, who presented with abdominal pain and weight loss. The ulcerated lesion was highly suspicious for malignancy radiologically and endoscopically. The patient underwent laparoscopic right hemicolectomy, and the lesion was diagnosed as a cecal submucosal lipoma pathologically.

CASE REPORT

A 68-year-old woman with history of hypertension, coronary artery disease, hypercholesterolemia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and arthritis, presented with abdominal pain for 1 mo and 10 pounds weight loss within 7 mo. The patient noted that the pain was in the right abdomen with a gradual onset and it was relieved after passing stool. The pain was 5/10 on the pain scale. The patient had no constipation or bloody stool. Physical examination of the abdomen revealed no masses or tenderness. Stool examination was negative for occult blood. The hemoglobin level was 10.6 g/dL (normal: 12.0-16.0 g/dL). Serum carcinoembryonic antigen level was within normal limits. Helical computed tomography (CT) imaging of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous and enteric contrast showed a cecal mass extending into the lumen with marked wall thickening, and multiple subcentimeter lymph nodes in the abdominal right lower quadrant. The CT diagnosis was that inflammatory vs neoplastic process could not be differentiated, and correlation with colonoscopy and biopsy were recommended. The following colonoscopy examination revealed an ulcerated mass located in the cecum, and the colonoscope could not pass beyond the lesion that appeared grossly malignant. Multiple biopsies from the lesion were obtained and sent for pathology. Histopathologic examination of biopsy specimens showed colonic mucosa with areas of acutely inflamed fibrous exudates and no identifiable malignancy.

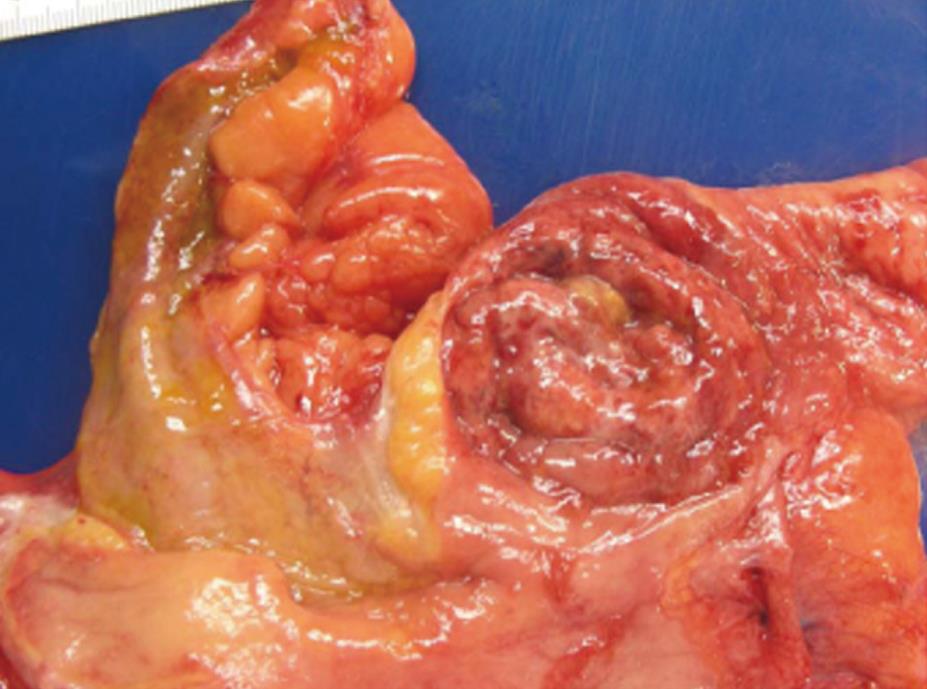

Because of the radiological and endoscopical suspicion of malignancy and even though no malignancy was identified in biopsy specimens, the patient underwent laparoscopic right hemicolectomy. Pathological gross examination showed a cecal ulcerated mass with a broad base measuring 6.0 cm × 5.1 cm (Figure 1). The ulcerated surface was covered with green/grey necrotic and mucinous material. Cut sections showed the ulcerated lesion was within the submucosa with a tan-yellow appearance and soft consistency. The lesion had no clear border with the surrounding tissues. Histopathologic examination revealed that the mass was located in the submucosa and composed of mature adipose tissue. The adipose tissue had no demarcated border to the surrounding tissue, and even protruded into the adjacent submucosa which was covered by chronic inflamed cecal mucosa (Figure 2A and B). The overlying mucosa was ulcerated and replaced by granulation tissue with acute and chronic inflammatory cells infiltration (Figure 2C). There was no carcinoma identified. The pathology diagnosis was cecal submucosal lipoma with overlying mucosa ulceration.

Figure 1 Gross photograph of broad-based and ulcerated mass in cecum (6.

0 cm in greatest dimension) mimicking malignancy.

Figure 2 Histopathologic examination.

A: Submucosal mass is composed of mature adipose tissue covered by granulation tissue with inflammatory cells infiltration (HE stain, × 100); B: Junction of ulcerated mass and adjacent cecal mucosa (HE stain, × 100). The submucosal lipoma has no defined margin to the surrounding tissues. The cecal mucosa presents with chronic inflammation; C: Overlying cecal mucosa replaced by granulation tissue with acute and chronic inflammatory cells infiltration (HE stain, × 400).

DISCUSSION

Lipomas are rare nonepithelial benign tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, and are found most frequently in the cecum and ascending colon. Weinberg and Feldman reviewed 1310 autopsies and found an incidence of 4.4%[8]. However, a meta-analysis by these same investigators identified 135 gastrointestinal lipomas in over 60 000 autopsies, with an incidence of 0.2%[8]. Colonic lipomas arise in the submucosa but occasionally extend into the muscularis propria or subserosa[3,9,10]. Usually, the lipomas are solitary, but can be multiple[11]. A rare lipomatosis syndrome, with numerous lipomas throughout the bowel, has been described[12,13]. Colonic lipomas usually do not cause symptoms and are often discovered incidentally at colonoscopy, surgery or autopsy. Only 25% of patients with colonic lipoma develop symptoms. When lipomas are larger than 2 cm in diameter they may cause symptoms including abdominal pain, diarrhea or constipation, weight loss, bowel obstruction either secondary to intussuseption or through direct luminal protrusion of the enlarging mass. Rarely, ulceration of the overlying mucosa may cause clinically apparent bleeding or chronic anemia[2-6].

Colonic lipomas are mainly found in the ascending colon and cecum, and typically appear grossly as small polypoid masses with a wide base and normal overlying mucosa[3,14]. The incidence of lipomas relative to all polyploid lesions of the large intestine is reported to range from 0.035% to 4.4%[15]. Various imaging modalities can indicate the diagnosis of colonic lipomas[3,4,14]. In spite of this, colonic lipomas continue to present difficulties in the preoperative differentiation between malignant and benign colonic neoplasm. Barium enema may reveal an ovoid filling defect with well-defined borders. A so-called “squeeze sign”, indicating a change in size and shape of a radiolucent lesion in response to peristalsis or the application of external pressure to the abdomen, can sometimes be elicited. CT scan may demonstrate a well-circumscribed intraluminal mass with absorption densities characteristic of fatty tissue. In the current case, CT scan did not show the typical features of lipoma. This was probably due to the large ulcerated mass with a broad base, unclear border to the surrounding tissues, and granulation tissue formation, which are different from the typical polypoid mass containing fatty tissue and protruding into the lumen. Endoscopy can usually distinguish lipomas from cancer or other tumors. Lipomas are seen as smooth, rounded yellowish polyps with a thick stalk or broad-based attachment. Typical colonoscopic features are the “cushion sign” or “pillow sign” (pressing forceps against the lesion results in depression or pillowing of the mass) and the “naked fat sign” (extrusion of yellowish fat at the biopsy site)[4]. Usually, the mucosa overlying a colonic lipoma is intact. In rare cases, as in the present patient, colonoscopy may reveal large-sized flat-shaped mass with ulceration that may lead to a impression of malignancy[7].

The etiology of gastrointestinal lipomas is not yet well understood[16]. In the majority of cases they are true neoplastic lipomas. They arise from the submucosa with a well-circumscribed margin, and protrude into the gastrointestinal lumen. They have a polypoid appearance, and rarely extend to muscularis propria, even subserosa. However, sometimes, the lipoma may be a result of chronic inflammation, especially in the cecum. The chronic inflammatory process may result in abnormal intestinal motility and this may cause the mucosa to pull away from the deeper submucosa, resulting in the creation of a tissue space with subsequent adipose tissue deposition. The deposited adipose tissues have no well-defined margins with adjacent tissues, and the overlying and adjacent colonic mucosa always presents with inflammatory changes, as in our current case. In this situation, it is better to call this a “pseudolipoma” to distinguish it from the true neoplastic lipoma. However, the differentiation of neoplastic lipoma and pseudolipoma is still controversial and not well recognized.

Generally, small colonic pedunculated lipomas can be safely removed endoscopically. Endoscopic resection of large colonic lipomas remains controversy. Surgical resection is recommended for larger lipomas to relieve the symptoms or exclude malignancy. Colostomy with lipomectomy and limited colon resection are considered an adequate treatment for certain lipomas diagnosed preoperatively. A segmental resection, hemicolectomy or subtotal colectomy may be necessary in cases when diagnosis is questionable or when a complication occurs. If the preoperative diagnosis of colonic lipoma can be made correctly, the extent of surgery may be appropriately limited[17,18].

In conclusion, colonic lipomas are rare nonepithelial benign tumors. Their accurate preoperative diagnosis is difficult and they can be mistaken for malignancy, especially when the lesion is large in size, and with ulceration. The etiology can be that of a true neoplasm or that of an inflammatory process. A surgical approach remains the treatment of choice for large and complicated cases.