Published online Feb 15, 2026. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v18.i2.114690

Revised: November 9, 2025

Accepted: December 15, 2025

Published online: February 15, 2026

Processing time: 130 Days and 16.6 Hours

Advanced pancreatic cancer (PC) is associated with a poor prognosis. The inte

To assess the short-term and long-term efficacy and safety of ICWM compared with Western medicine (WM) as a standalone treatment for advanced PC.

We enrolled 136 patients with advanced PC admitted to Henan Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Me

The median overall survival was 12.91 months and 10.64 months in the ICWM and WM groups, while the median progression-free survival was 5.12 months and 3.55 months, respectively. The disease control rate was significantly higher in the ICWM group than that in the the WM group, while the myelosuppression was significantly milder. The serum tumor markers carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 and CA125 showed a significant downward trend before and after treatment in the ICWM group, whereas only CA19-9 showed a significant decrease in the WM group. Post-treatment, both groups showed an upward trend in natural killer cells and CD3+, CD4+, and CD4+/CD8+ lymphocytes compared with pre-treatment, with the ICWM group exhibiting a more pronounced increase. The two groups showed no significant differences in hepatic and renal function impairment.

ICWM extended survival in patients with advanced PC, improved long-term efficacy, controlled local lesions, reduced serum tumor markers, enhanced immune function, and improved short-term outcomes, with a favorable safety profile.

Core Tip: Advanced pancreatic cancer (PC) is associated with poor prognosis. In this double-center retrospective cohort study, the median survival time in the Western medicine (WM) group was 10.67 months, while the integration of Chinese and WM group demonstrated an additional 2.24 months of survival. This breakthrough exceeded the conventional 12-month median survival time threshold for PC, nearing the survival outcomes achieved with targeted immunotherapy and combination chemotherapy, which are at the forefront of precision treatments. These findings suggest that integrated Chinese and WM models may provide survival advantages to patients with advanced PC.

- Citation: Wang YR, Wang JQ, Chen XJ, Yan Y, Zhang Y, Li MY, Wang W, Fan TY, Jiao PF, Zhou CF. Efficacy and safety of integrated Chinese and Western medicine in advanced pancreatic cancer: A double-center retrospective cohort study. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2026; 18(2): 114690

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v18/i2/114690.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v18.i2.114690

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is one of the most aggressive malignancies of the gastrointestinal tract and is characterized by an insidious onset, high invasiveness, and rapid progression. Approximately 90% of patients with PC are diagnosed at intermediate or advanced stages[1]. However, the development of effective therapeutic strategies for PC is slow and lags significantly behind that for other malignancies. Traditional chemotherapy regimens, the first-line treatment for advanced PC[2], yield a 5-year survival rate of only 2%-9%[3], with reports revealing that PC is the second leading cause of cancer-associated death[4].

The therapeutic approach of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is rooted in the harmonization of yin-yang and qi-blood. This is achieved through multifaceted actions, including modulation of the immune system, remodeling of the tumor microenvironment, and inhibition of tumor microvessels, which collectively enhance the host immune defense and potentiate the efficacy of antitumor therapies[5,6]. Mechanistic investigations demonstrated that a novel artemisinin derivative, ZQJ29, induces ferroptosis in PC cells via PARP1 inhibition, highlighting its potential as a lead compound in the development of novel anticancer drug development[7]. Clinical research on the TCM compound Qingyi Xiaoji Formula has indicated its utility in PC treatment by mitigating chemotherapy-induced toxicity, improving patient quality of life, and alleviating common side effects[8]. Despite these promising findings, the integration of TCM with conventional therapies requires validation through more robust clinical trials to establish their therapeutic efficacy and safety profile, and thus facilitate their widespread adoption in PC management. Therefore, in this retrospective cohort study, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of integration of Chinese and Western medicine (ICWM) vs Western medicine (WM) alone for the treatment of advanced PC, with the aim to provide scientific evidence for the broader application of integrated approaches in treatment.

A total of 136 patients with advanced PC who were admitted to Henan Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Henan Provincial People’s Hospital between 2019 and 2024 were included in this study. The patients were divided into two distinct groups according to the treatment modality: (1) The combined ICWM group (n = 66); and (2) The WM group (n = 70). The ICWM group comprised 37 males and 29 females; 36 patients were under 65 years of age, and 30 were 65 years or older. The performance status (PS) scores were 0 and 1 in 45 patients and ≥ 2 in 21 patients. Histologically, 62 cases were ductal adenocarcinomas and 4 cases were of other types. Differentiation levels were low in 50 cases, moderate in 15, and high in one. The distribution by pancreatic location was as follows: (1) Head (36 cases); (2) Body (4 cases); (3) Tail (11 cases); and (4) Mixed locations (15 cases). The TNM stage was stage III in 11 cases and stage IV in 55; additional findings included 8 cases of ascites and 39 cases of hepatic impairment. Treatment regimens included chemotherapy in 48 patients, chemotherapy combined with targeted therapy in 4, chemotherapy with immunotherapy in 1, radiofrequency ablation in 6, and radioactive seed implantation brachytherapy in 7. The WM group comprised 39 males and 31 females. Thirty-four patients were < 65 years, and 36 were ≥ 65 years. The PS scores were 0 and 1 in 56 patients and ≥ 2 in 14 patients. Histologically, 63 cases were ductal adenocarcinomas, with seven cases of other types. The differentiation levels included 46 cases with low differentiation, 20 with moderate differentiation, and four with high differentiation. The tumor locations were as follows: (1) Pancreatic head (51 cases); (2) Body (three cases); (3) Tail (seven cases); and (4) Mixed sites (nine cases). TNM staging revealed stages III and IV disease in 12 patients and 58 patients, respectively. Ascites was present in eight cases and hepatic impairment in 46 cases. Treatment options included chemotherapy in 50 patients and chemotherapy combined with targeted therapy in two patients. Chemotherapy was combined with immunotherapy in eight cases, radiofrequency ablation in five, and radioactive seed implantation brachytherapy in five. There were no statistically significant differences in the general data of the two groups (P > 0.05), indicating comparability (Table 1). This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Henan Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

| Characteristics | Integration of Chinese and Western medicine group (n = 66) | Western medicine group | χ2 | P value |

| Gender | 0.002 | 0.968 | ||

| Female | 29 (43.9) | 31 (44.3) | ||

| Male | 37 (56.1) | 39 (55.7) | ||

| Age (years) | 0.485 | 0.486 | ||

| < 65 | 36 (54.5) | 34 (48.6) | ||

| ≥ 65 | 30 (45.5) | 36 (51.4) | ||

| Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status | 2.483 | 0.115 | ||

| 0 and 1 | 45 (68.2) | 56 (80.0) | ||

| 2 | 21 (31.8) | 14 (20.0) | ||

| Histological type | 0.709 | 0.400 | ||

| Ductal adenocarcinoma | 62 (93.9) | 63 (90.0) | ||

| Other | 4 (6.1) | 7 (10.0) | ||

| Differentiation grade | 2.566 | 0.277 | ||

| Poorly differentiated | 50 (75.8) | 46 (65.7) | ||

| Moderately differentiated | 15 (22.7) | 20 (28.6) | ||

| Well differentiated | 1 (1.5) | 4 (5.7) | ||

| Primary site | 5.005 | 0.171 | ||

| Head of pancreas | 36 (54.5) | 51 (72.9) | ||

| Body of pancreas | 4 (6.1) | 3 (4.3) | ||

| Tail of pancreas | 11 (16.7) | 7 (10.0) | ||

| Mixed | 15 (22.7) | 9 (12.9) | ||

| TNM stage | 0.636 | 0.425 | ||

| Stage III | 11 (16.7) | 12 (17.1) | ||

| Stage IV | 55 (83.3) | 58 (82.9) | ||

| Ascites presence | ||||

| Present | 8 (12.1) | 8 (11.4) | ||

| Absent | 58 (87.9) | 62 (88.6) | ||

| Hepatic impairment | ||||

| Present | 39 (59.1) | 46 (65.7) | ||

| Absent | 27 (40.9) | 24 (34.3) | ||

| Treatment regimen | 6.464 | 0.167 | ||

| Chemotherapy | 48 (72.7) | 50 (71.4) | ||

| Chemotherapy plus targeted therapy | 4 (6.1) | 2 (2.9) | ||

| Chemotherapy plus immunotherapy | 1 (1.5) | 8 (11.4) | ||

| Radiofrequency ablation | 6 (9.1) | 5 (7.1) | ||

| Radioactive seed implantation brachytherapy | 7 (10.6) | 5 (7.1) |

The diagnostic criteria followed the European Society of Medical Oncology Clinical Practice Guidelines for PC, published in September 2023 by the European Society of Medical Oncology[9]. Diagnosis was confirmed through pathological examination of PC or clinical diagnosis based on symptoms, physical signs, laboratory tests, and imaging studies.

The clinical staging criteria followed the PC staging standards in the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual[10], which includes patients classified as having stage III or IV PC.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients who met the diagnostic criteria for WM and were diagnosed with primary PC through pathological or imaging examinations; (2) Aged ≥ 18 years; (3) Patients who have received at least three courses of TCM treatment within 6 months of the initial consultation; (4) Detailed treatment plans, efficacy evaluation results, and adverse reaction records; and (5) Confirmed date of death or last follow-up.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients with concurrent primary malignancies; (2) Patients with autoimmune or active infections; (3) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status score of ≥ 3; (4) Pediatric cases, pregnant individuals, or those with severe mental health conditions; (5) Patients who have severe infections or other organ diseases; and (6) Patients with significant deficiencies in clinical data or relevant examinations.

(1) The inclusion criteria were met, but the treatment course was insufficient for analysis; and (2) Patients for whom time to progression and overall survival (OS) could not be assessed.

The ICWM group used Chinese medicine as the foundation for each hospitalization combined with multidisciplinary treatments, including chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy, tailored to clinical needs. TCM treatments were administered in 21-28-day cycles, with evaluations performed after two cycles. For patients with stable disease (SD), subsequent treatment intervals may be extended, and for those with disease progression, treatment regimens will be adjusted. Western medical treatment followed the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines and incorporated chemotherapy, radiofrequency ablation, particle implantation, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy. Follow-up continued until July 31, 2025.

Long-term efficacy: OS was defined as the time from diagnosis of advanced PC to death from any cause. Deceased subjects were considered to have complete data, and OS was defined as the time span from diagnosis until death. Incomplete data included survivors and those who were lost to follow-up. Survivors were treated as right-censored, with OS defined as the time from diagnosis to the last follow-up visit; subjects lost to follow-up were treated as left-censored, and OS was defined as the time from diagnosis to the last follow-up visit.

Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from the diagnosis of advanced PC until the first tumor progression, death (from any cause), or the end of follow-up.

Short-term efficacy: (1) Efficacy in solid tumors: Progressive disease (PD), SD, partial response (PR), and complete response (CR) were assessed based on the 2009 revised New Solid Tumor Efficacy Evaluation Criteria, RECIST (version 1.1)[11]. The disease control rate (DCR) was calculated as the SD rate + PR rate + CR rate. The objective response rate (ORR) was calculated as the PR rate + CR rate. Two physicians conducted all assessments; (2) Serum tumor markers: The levels of carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9, CA125, and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) were measured in both patient groups before (prior to the first treatment) and after treatment (prior to the third treatment) for evaluation; (3) Immune function: The numbers of CD3+, CD4+, CD4+/CD8+, and natural killer (NK) cells were assessed in both groups before (prior to the first treatment) and after (prior to the third treatment) treatment; and (4) Safety evaluation: Adverse events were graded and documented according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events of the United States National Cancer Institute. Adverse reactions were classified as grades I-IV. The primary observations focused on the incidence of grade I-IV adverse reactions during treatment in both groups, including myelosuppression and hepatorenal impairment.

Data were analyzed and visualized using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 26.0 and R 4.3.3 statistical software. Quantitative data are presented as the mean ± SD for normally distributed data, and non-normally distributed data are presented as medians with interquartile ranges. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method to estimate the median survival time (MST) and median modified PFS (mPFS), reported in months, with a 95%CI. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

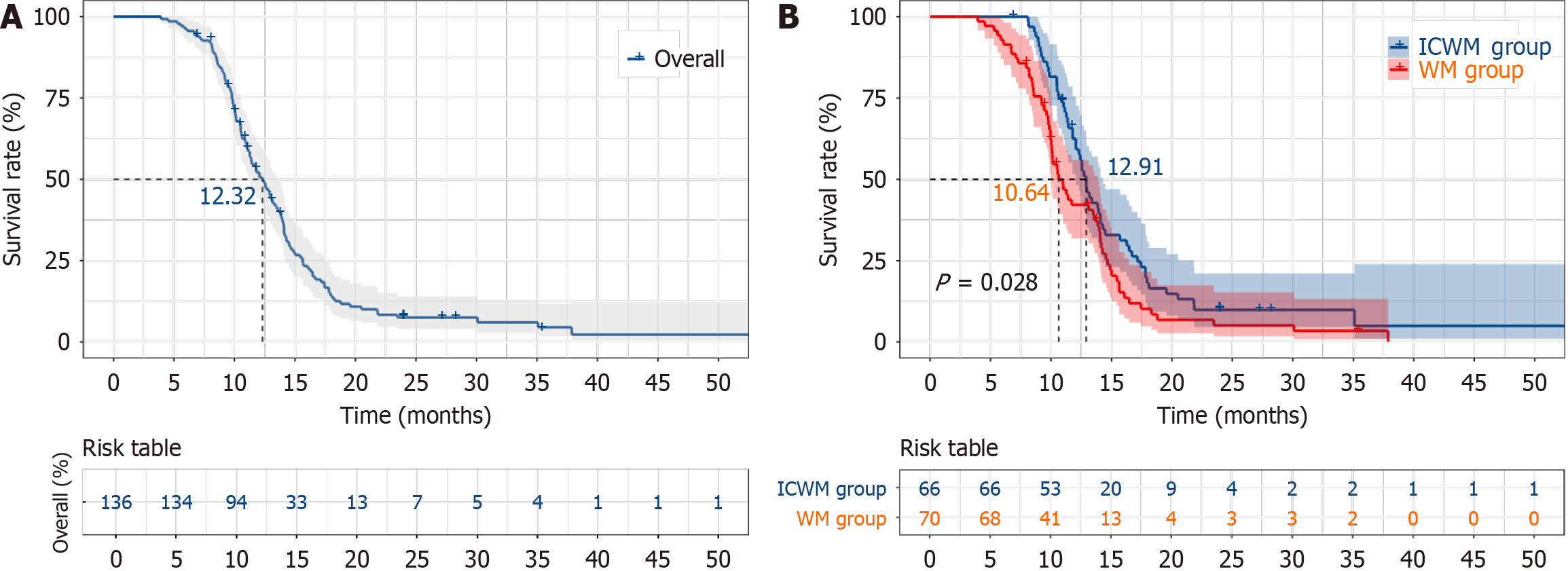

The MST of the 136 patients was 12.32 months (95%CI: 11.06-13.58). The 9-month, 12-month, 15-month, and 18-month survival rates were 82.9%, 54.6%, 26.7%, and 13.4%, respectively. The MST for patients in the ICWM group was 12.91 months (95%CI: 12.10-13.72), while that in the WM group was 10.64 months (95%CI: 9.41-11.87). The 9-month, 12-month, 15-month, and 18-month survival rates were 90.8%, 59.2%, 32.9%, and 16.4% in the ICWM group and 74.1%, 42.2%, 20.3%, and 8.5% in the WM group, respectively. The MST was significantly longer in the ICWM group than that in the WM group (P < 0.05; Figure 1).

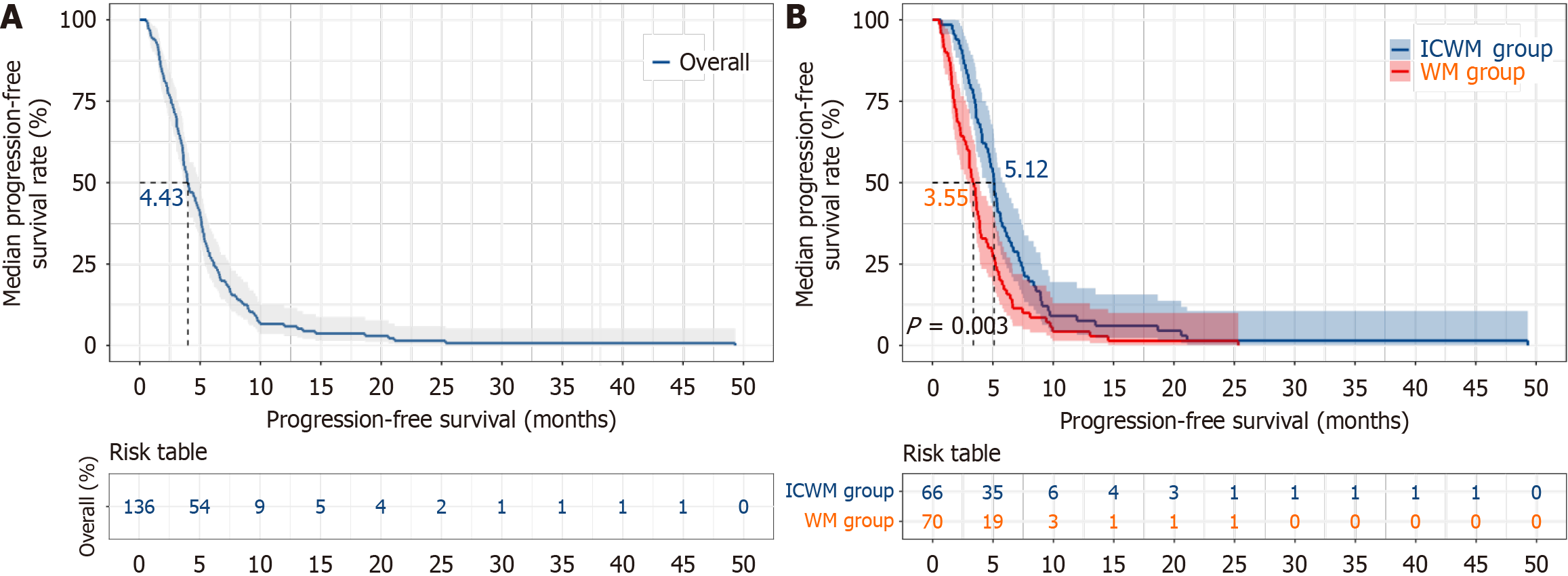

The median mPFS of the 136 patients was 4.43 months (95%CI: 3.38-5.28). Specifically, the mPFS for patients in the ICWM group was 5.12 months (95%CI: 4.74-5.50), while that for patients in the WM group was 3.55 months (95%CI: 3.07-4.03). The mPFS was significantly longer in the ICWM group than in the WM group (P < 0.05; Figure 2).

Efficacy in solid tumors: The DCR rate in the ICWM group was 62 patients, accounting for 96.9% of the total number of patients in the ICWM group. In the WM group, the DCR rate was 58 patients, representing 82.5% of the total number of patients in the WM group. The DCR rate was significantly higher in the ICWM group than in the WM group (P < 0.05). The PR, progressive disease, or ORR did not differ significantly between the two groups (Table 2).

| Group | Complete response | Partial response | Stable disease | Progressive disease | Disease control rate | Objective response rate |

| Integration of Chinese and Western medicine group (n = 66) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (21.2) | 48 (72.7) | 4 (6.1) | 62 (93.9)a | 14 (21.2) |

| Western medicine group (n = 70) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (21.4) | 45 (63.3) | 10 (14.3) | 58 (82.9) | 15 (21.4) |

The serum tumor markers CA199 and CA125 showed a significant decrease in the ICWM group after treatment (P < 0.05). However, in the WM group, only the CA199 Levels decreased significantly vs the levels before treatment (P < 0.05). The CEA levels did not differ significantly between the two groups before and after treatment (P > 0.05; Table 3).

| Group | Time | CA199 (U/mL) | CA125 (U/mL) | CEA (ng/mL) |

| Integration of Chinese and Western medicine group (n = 66) | Before treatment | 853.31 (20.70, 8560.03) | 55.90 (24.90, 252.70) | 5.67 (2.59, 18.83) |

| After treatment | 317.95 (28.35, 5593.16)a | 47.50 (16.80, 169.10)a | 6.94 (3.40, 21.81) | |

| Western medicine group (n = 70) | Before treatment | 455.29 (55.77, 2722.84) | 66.12 (23.67, 150.46) | 6.16 (3.30, 24.10) |

| After treatment | 628.21 (42.18, 1902.00)a | 67.65 (20.43, 200.30) | 8.81 (4.08, 28.38) |

Both the ICWM and WM groups exhibited an upward trend in NK cells and CD3+, CD4+, and CD4+/CD8+ lymphocytes after treatment vs before treatment (P < 0.05). However, the immune parameters in the ICWM group showed a more pronounced increase after treatment than those in the WM group (P < 0.05; Table 4).

| Group | Time | CD3+ (%) | CD4+ (%) | CD4+/CD8+ | NK (%) |

| Integration of Chinese and Western medicine group (n = 66) | Before treatment | 58.02 ± 4.48 | 35.01 ± 3.81 | 1.14 ± 0.13 | 5.85 ± 1.57a |

| After treatment | 69.98 ± 8.01a,b | 45.02 ± 3.47a,b | 1.83 ± 0.79a,b | 17.44 ± 3.68a,b | |

| Western medicine group (n = 70) | Before treatment | 58.71 ± 3.45 | 36.31 ± 3.84 | 1.17 ± 0.97 | 7.85 ± 0.97 |

| After treatment | 64.07 ± 4.47a | 38.95 ± 4.57a | 1.48 ± 0.11a | 14.94 ± 0.43a |

The incidences of grade II and III myelosuppression in the ICWM group were 14 cases and 6 cases vs 21 patients and 12 patients in the WM group; these represented 21.7% and 9.1% of the total in the ICWM group vs 30.0% and 17.1% in the WM group, respectively, showing statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). However, no significant differences were observed in hepatic or renal function impairment between the two groups (P > 0.05; Table 5).

| Group | Myelosuppression | Hepatic impairment | Renal impairment | |||||||||

| Grade I | Grade II | Grade III | Grade IV | Grade I | Grade II | Grade III | Grade IV | Grade I | Grade II | Grade III | Grade IV | |

| Integration of Chinese and Western medicine group (n = 66) | 30 | 14 | 6 | 1 | 12 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Western medicine group (n = 70) | 30 | 21 | 12 | 3 | 12 | 5 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| P value | 0.003 | 0.890 | 0.631 | |||||||||

In this study, we analyzed the clinical data of patients with advanced PC treated at Henan Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Henan Provincial People’s Hospital between January 2019 and December 2024. Patients were divided into the ICWM and WM groups according to the treatment modality. The MST was 12.91 months for the ICWM group compared with 10.64 months in WM group. A systematic review and network meta-analysis in

In terms of tumor response, the ORR did not differ significantly between the two groups. However, the DCR in the ICWM group was significantly higher, exceeding that reported for modified FOLFIRINOX (86.5%) and nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine (82.4%)[20,21]. These findings suggest that TCM contributes to the stabilization of local diseases. Among the tumor markers, serum CA19-9, CA125, and CEA levels remain important prognostic indicators in PC. A CA19-9 reduction is typically associated with a decreased tumor burden[22], while elevated CA125 Levels are often linked to metastasis and peritoneal involvement. In this study, only CA19-9 levels decreased significantly in the WM group, whereas both CA19-9 and CA125 levels declined in the ICWM group, suggesting a broader biomarker im

Safety evaluations demonstrated that hepatic and renal function impairments did not differ significantly between the groups. However, the incidence of grade II and III myelosuppression was significantly lower in the ICWM group, indicating the protective effect of TCM against chemotherapy-related hematological toxicity. These findings highlight the favorable safety profile of integrated therapies.

Guided by the core TCM principles of a holistic perspective and treatment based on syndrome differentiation, the integrated therapy used in this study employed a systematic and standardized approach. Unlike single-modality TCM treatments, this involves the dynamic adjustment of the therapeutic regimen in accordance with the progression of the patient’s condition and their constitutional changes. Unlike WM alone, it leverages multidimensional TCM participation across the entire treatment process, complementing modern medicine. Collectively, this study suggests that ICWM can prolong survival, control local disease, reduce tumor markers, enhance immune function, and improve both short-term and long-term efficacy, while maintaining safety.

This study has several limitations inherent to its dual-center retrospective cohort design. First, selection bias could have been introduced because of patient preferences in choosing a healthcare facility. Second, heterogeneity in treatment details exists between centers, and center effects may arise from variations in instrument calibration standards and clinical follow-up procedures. Third, the retrospective nature of the study precludes complete control for unmeasured confounding factors, and the relatively small sample size may limit the statistical power. Nevertheless, both hospitals included in this study are tertiary A-class hospitals in China, characterized by a high degree of standardization in diagnostic and therapeutic technologies. Furthermore, no statistically significant differences were observed in baseline characteristics between the two groups, which helped mitigate potential bias and enhance the reliability of the findings. Future research should involve randomized controlled trials with larger multicenter cohorts to further investigate and validate the efficacy and safety of ICWM in treating advanced PC, thereby providing higher-level evidence for clinical practice.

ICWM constitutes an effective and safe strategy for treating advanced PC, as evidenced by prolonged OS, improved local tumor control, reduced serum tumor markers, and enhanced immunological function.

| 1. | Wood LD, Canto MI, Jaffee EM, Simeone DM. Pancreatic Cancer: Pathogenesis, Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Gastroenterology. 2022;163:386-402.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 599] [Article Influence: 149.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rehman M, Khaled A, Noel M. Cytotoxic Chemotherapy in Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2022;36:1011-1018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | McGuigan A, Kelly P, Turkington RC, Jones C, Coleman HG, McCain RS. Pancreatic cancer: A review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:4846-4861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1338] [Cited by in RCA: 1341] [Article Influence: 167.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (47)] |

| 4. | Stoop TF, Javed AA, Oba A, Koerkamp BG, Seufferlein T, Wilmink JW, Besselink MG. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2025;405:1182-1202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 123.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Arnab MKH, Islam MR, Rahman MS. A comprehensive review on phytochemicals in the treatment and prevention of pancreatic cancer: Focusing on their mechanism of action. Health Sci Rep. 2024;7:e2085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhang Y, Xu H, Li Y, Sun Y, Peng X. Advances in the treatment of pancreatic cancer with traditional Chinese medicine. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1089245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chen J, Yue L, Pan Y, Jiang B, Wan J, Lin H, Guo F, Li H, Li Y, Zhao Q. Novel Cyano-Artemisinin Dimer ZQJ29 Targets PARP1 to Induce Ferroptosis in Pancreatic Cancer Treatment. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2025;12:e01935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Song LB, Gao S, Zhang AQ, Qian X, Liu LM. Babaodan Capsule () combined with Qingyi Huaji Formula () in advanced pancreatic cancer-a feasibility study. Chin J Integr Med. 2017;23:937-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Conroy T, Pfeiffer P, Vilgrain V, Lamarca A, Seufferlein T, O'Reilly EM, Hackert T, Golan T, Prager G, Haustermans K, Vogel A, Ducreux M; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Pancreatic cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2023;34:987-1002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 342] [Article Influence: 114.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kang H, Kim SS, Sung MJ, Jo JH, Lee HS, Chung MJ, Park JY, Park SW, Song SY, Park MS, Bang S. Evaluation of the 8th Edition AJCC Staging System for the Clinical Staging of Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:4672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, Rubinstein L, Shankar L, Dodd L, Kaplan R, Lacombe D, Verweij J. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15860] [Cited by in RCA: 22774] [Article Influence: 1339.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Mastrantoni L, Chiaravalli M, Spring A, Beccia V, Di Bello A, Bagalà C, Bensi M, Barone D, Trovato G, Caira G, Giordano G, Bria E, Tortora G, Salvatore L. Comparison of first-line chemotherapy regimens in unresectable locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2024;25:1655-1665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sha H, Tong F, Ni J, Sun Y, Zhu Y, Qi L, Li X, Li W, Yang Y, Gu Q, Zhang X, Wang X, Zhu C, Chen D, Liu B, Du J. First-line penpulimab (an anti-PD1 antibody) and anlotinib (an angiogenesis inhibitor) with nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine (PAAG) in metastatic pancreatic cancer: a prospective, multicentre, biomolecular exploratory, phase II trial. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9:143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gao Y, Chen S, Sun J, Su S, Yang D, Xiang L, Meng X. Traditional Chinese medicine may be further explored as candidate drugs for pancreatic cancer: A review. Phytother Res. 2021;35:603-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Schultheis B, Reuter D, Ebert MP, Siveke J, Kerkhoff A, Berdel WE, Hofheinz R, Behringer DM, Schmidt WE, Goker E, De Dosso S, Kneba M, Yalcin S, Overkamp F, Schlegel F, Dommach M, Rohrberg R, Steinmetz T, Bulitta M, Strumberg D. Gemcitabine combined with the monoclonal antibody nimotuzumab is an active first-line regimen in KRAS wildtype patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: a multicenter, randomized phase IIb study. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:2429-2435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouché O, Guimbaud R, Bécouarn Y, Adenis A, Raoul JL, Gourgou-Bourgade S, de la Fouchardière C, Bennouna J, Bachet JB, Khemissa-Akouz F, Péré-Vergé D, Delbaldo C, Assenat E, Chauffert B, Michel P, Montoto-Grillot C, Ducreux M; Groupe Tumeurs Digestives of Unicancer; PRODIGE Intergroup. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817-1825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4838] [Cited by in RCA: 5896] [Article Influence: 393.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (23)] |

| 17. | Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, Chiorean EG, Infante J, Moore M, Seay T, Tjulandin SA, Ma WW, Saleh MN, Harris M, Reni M, Dowden S, Laheru D, Bahary N, Ramanathan RK, Tabernero J, Hidalgo M, Goldstein D, Van Cutsem E, Wei X, Iglesias J, Renschler MF. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1691-1703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4035] [Cited by in RCA: 5141] [Article Influence: 395.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (12)] |

| 18. | Chen MM, Gao Q, Ning H, Chen K, Gao Y, Yu M, Liu CQ, Zhou W, Pan J, Wei L, Dou W, Zhang D, Zhu L, Zhang Q, Chen R, Zhang Z. Integrated single-cell and spatial transcriptomics uncover distinct cellular subtypes involved in neural invasion in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2025;43:1656-1676.e10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Maddipati R. Metastatic heterogeneity in pancreatic cancer: mechanisms and opportunities for targeted intervention. J Clin Invest. 2025;135:e191943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Stein SM, James ES, Deng Y, Cong X, Kortmansky JS, Li J, Staugaard C, Indukala D, Boustani AM, Patel V, Cha CH, Salem RR, Chang B, Hochster HS, Lacy J. Final analysis of a phase II study of modified FOLFIRINOX in locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2016;114:737-743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhang F, Wang Y, Yang F, Zhang Y, Jiang M, Zhang X. The Efficacy and Safety of PD-1 Inhibitors Combined with Nab-Paclitaxel Plus Gemcitabine versus Nab-Paclitaxel Plus Gemcitabine in the First-Line Treatment of Advanced Pancreatic Cancer: A Retrospective Monocentric Study. Cancer Manag Res. 2022;14:535-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Xu HX, Li S, Wu CT, Qi ZH, Wang WQ, Jin W, Gao HL, Zhang SR, Xu JZ, Liu C, Long J, Xu J, Ni QX, Yu XJ, Liu L. Postoperative serum CA19-9, CEA and CA125 predicts the response to adjuvant chemoradiotherapy following radical resection in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreatology. 2018;18:671-677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Liu L, Xu HX, Wang WQ, Wu CT, Xiang JF, Liu C, Long J, Xu J, Fu de L, Ni QX, Houchen CW, Postier RG, Li M, Yu XJ. Serum CA125 is a novel predictive marker for pancreatic cancer metastasis and correlates with the metastasis-associated burden. Oncotarget. 2016;7:5943-5956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sun Y, Zhang P, Ma J, Chen Y, Huo X, Song H, Zhu Y. Mechanism of traditional drug treatment of cancer-related ascites: through the regulation of IL-6/JAK-STAT3 pathway. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2025;77:264-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Xu X, Wang N, Li Y, Fan S, Mu B, Zhu J. Acupuncture Potentiates anti-PD-1 Efficacy by Promoting CD5(+) Dendritic Cells and T Cell-Mediated Tumor Immunity in a Mouse Model of Breast Cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2025;1-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wang D, Cui Q, Yang YJ, Liu AQ, Zhang G, Yu JC. Application of dendritic cells in tumor immunotherapy and progress in the mechanism of anti-tumor effect of Astragalus polysaccharide (APS) modulating dendritic cells: a review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;155:113541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Li S, Chen X, Shi H, Yi M, Xiong B, Li T. Tailoring traditional Chinese medicine in cancer therapy. Mol Cancer. 2025;24:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 64.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/