Published online Feb 15, 2026. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v18.i2.113673

Revised: November 3, 2025

Accepted: December 10, 2025

Published online: February 15, 2026

Processing time: 155 Days and 13 Hours

Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) beyond the Milan criteria or with portal vein tumor thrombosis are often excluded from the transplant list owing to aggressive biology and recurrence risk. While high alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) sig

To assess the prognostic value of PIVKA-II in normal AFP HCC.

Retrospective cohort of 113 patients with normal AFP and normal or elevated PIVKA-II. “Aggressive” tumors were defined as beyond Milan and/or portal vein tumor thrombosis (n = 63); others were non-aggressive (n = 50). Receiver ope

This study included 78 men and 35 women; mean age 58.4 ± 11.1 years; 62.8% with decompensated cirrhosis. PIVKA-II was higher in aggressive tumors: Me

In normal AFP HCC, PIVKA-II discriminates aggressive biology. A cut-off of 1609.5 mAU/mL balances sensitivity and specificity; 400 mAU/mL favors sensitivity; ≥ 4000 mAU/mL delineates an ultra-high-risk subgroup. Findings support the incorporation of PIVKA-II into risk stratification.

Core Tip: Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) often underperforms as a biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Our study shows that protein induced by vitamin K absence/antagonist-II (PIVKA-II) better indicates aggressive disease when AFP is normal. In normal AFP HCC, PIVKA-II ≥ 400 mAU/mL is linked to high-risk features, and ≥ 4000 mAU/mL identifies an especially aggressive group. Using PIVKA-II in surveillance and treatment planning could improve early detection and outcomes, particularly for AFP-negative patients. Transplant choices may change: Low PIVKA-II, even with large tumors, may suggest slower disease, while very high PIVKA-II within size limits signals higher post-transplant recurrence risk. These findings support updating HCC management guidelines and practice.

- Citation: Abbas Z, Gazder DP, Hyder Z, Qadeer MA, Abbas M. Serum protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II predicts aggressive tumor biology in alpha-fetoprotein-normal hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2026; 18(2): 113673

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v18/i2/113673.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v18.i2.113673

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a leading cause of cancer-related mortality, with prognosis largely determined by tumor burden and vascular invasion[1]. Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) is widely used to gauge tumor aggressiveness; higher levels generally indicate more aggressive disease and inform prognosis and treatment selection[2]. However, up to 30% of HCC cases present with normal AFP, limiting early risk stratification[3]. These normal AFP cases pose diagnostic and prognostic challenges because aggressive disease can still occur despite normal values[4]. Thus, AFP alone may not adequately reflect tumor behavior in this subgroup.

Protein induced by vitamin K absence/antagonist-II (PIVKA-II), also known as des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin, has emerged as a complementary biomarker, particularly in AFP-negative cohorts[5,6]. It is produced by defective vitamin K-dependent carboxylation in malignant hepatocytes, and its serum levels correlate with tumor size, vascular invasion, and poor differentiation in HCC[7]. Despite its diagnostic and prognostic utility in Asian guidelines, PIVKA-II remains underutilized in Western protocols, where AFP and imaging predominate[8]. We therefore evaluated the predictive value of PIVKA-II in HCC patients with normal AFP, focusing on its ability to identify aggressive tumor biology[9]. To our knowledge, this is among the first studies dedicated specifically to the normal AFP HCC population.

This retrospective study analyzed 113 HCC patients with normal AFP levels (≤ 20 ng/mL) and available PIVKA-II measurements, seen over the past three years at our center. Clinical data, including tumor characteristics and treatment outcomes, were collected. Patients were categorized into two groups based on tumor behavior: Aggressive tumors that exceeded Milan criteria, or there was portal vein tumor thrombosis (PVTT), and non-aggressive tumors (within Milan criteria and no PVTT). Clinical parameters included etiology, liver function, and tumor characteristics. PIVKA-II levels were measured via the ARCHITECT PIVKA-II chemiluminescence immunoassay 3C10 with a cutoff value of 40 mAU/mL. The AFP concentration was analyzed using an ARCHITECT AFP 3P36 (Abbott Laboratories, IL, United States) kit, which uses a two-step immunoassay for quantitative measurement. AFP was considered normal if the value was less than 20 ng/mL.

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they had a confirmed diagnosis of HCC, either through histopathological examination or non-invasive imaging criteria, specifically demonstrating arterial hyperenhancement with washout on contrast-enhanced computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging. Additionally, participants were required to have normal AFP levels, defined as ≤ 20 ng/mL at diagnosis. Furthermore, pre-treatment serum PIVKA-II measurements needed to be available in the medical records. To ensure real-world heterogeneity in the study population, patients with various etiologies of liver disease were included, encompassing hepatitis B and C viral infections, alcohol-related liver disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and autoimmune liver disease.

Patients were excluded from the study if they presented with mixed histology, specifically intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma or mixed HCC-cholangiocarcinoma. Furthermore, those with concurrent malignancies, including extrahepatic cancers or metastatic HCC, were not eligible for participation. Additionally, patients who had received any prior anti-tumor therapy, such as chemotherapy, transarterial chemoembolization, microwave ablation, or resection before PIVKA-II measurement, were excluded from the study. Moreover, the study excluded patients who were on vitamin K antagonists, specifically those taking warfarin or who had received recent vitamin K supplementation, as these medications could potentially alter PIVKA-II levels.

While the study did not explicitly calculate a sample size, the cohort of 113 patients aligns with similar retrospective studies evaluating PIVKA-II in AFP-negative HCC. With 113 patients, our study had > 80% power to detect the observed difference in mean PIVKA-II levels at α = 0.05, based on descriptive sensitivity check. This sample size is in line with prior studies of PIVKA-II in HCC (e.g., Saeki et al[10], n = 90).

For baseline comparisons, continuous variables, such as PIVKA-II levels, were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test due to their non-normal distribution as evident from the Shapiro-Wilk test. Categorical variables, including etiology and decompensation, were analyzed using either Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, where appropriate. A two-tailed P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to determine the optimal PIVKA-II cutoff for predicting aggressive behavior using Youden’s index, which maximizes the sum of sensitivity and specificity. The area under the ROC curve was calculated to evaluate diagnostic accuracy. Significant variables for aggressive tumors with univariable P < 0.10 were entered into a multivariable logistic regression. Adjusted odds ratios and P values are reported. The statistical analysis was performed by IBM SPSS Statistics 30.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States).

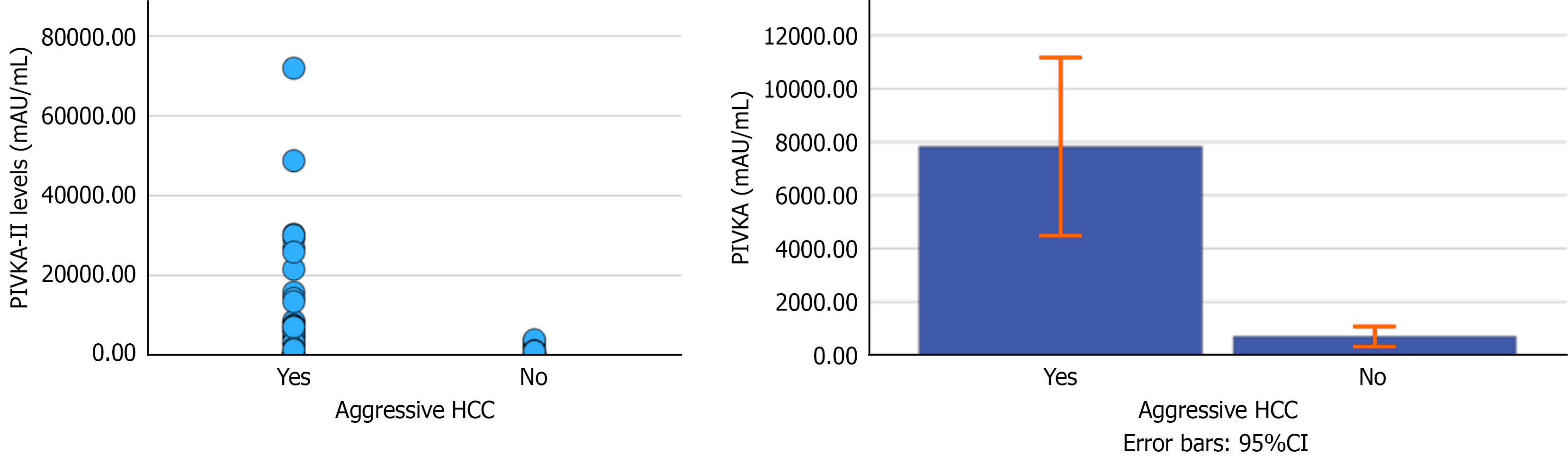

A total of 113 patients were included, with a mean age of 58.4 ± 11.1 years; 69% were male. Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics, including etiologies of liver disease and liver function status. Seventy-one (62.8%) patients had decompensated liver disease due to ascites or encephalopathy. Out of 63 patients with aggressive tumors, 30 patients fulfilling the Milan criteria also had portal PVTT. In only 4 patients, PVTT was present with HCC of less than the Milan criteria. Patients with aggressive tumors had markedly higher PIVKA-II levels than those with non-aggressive tumors (n = 50): Median with interquartile range values were 2785 mAU/mL (222-8152) vs 239 mAU/mL (55-727), P < 0.001 (Figure 1). There was no significant difference in the PIVKA-II levels of patients with (n = 34) and without PVTT (n = 29) within the aggressive groups (P = 0.202 by Mann-Whitney U test).

| Variables | Values |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 58 (52-66) |

| Gender (male/female) | |

| Male | 78 (69) |

| Female | 5 (31) |

| Etiology | |

| HC | 49 (43.4) |

| HB | 27 (23.9) |

| HB + HD | 3 (2.6) |

| HC + HB | 2 (1.7) |

| MASLD | 6 (14.1) |

| Alcohol | 6 (5.3) |

| Autoimmune liver disease | 6 (5.3) |

| Cryptogenic | 4 (3.5) |

| Lab parameters, median (IQR) | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.0 (9.3-13.0) |

| White cell count (× 109/L) | 6.8 (5.0-9.0) |

| Platelets (× 109/L) | 116.5 (84-168) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.3 (0.7-2.3) |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 47.0 (30.0-73.0) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L) | 58 (37.5-87.5) |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 96.5 (140.5-219.0) |

| International normalized ratio | 1.27 (1.10-1.44) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.76 (3.10-3.61) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.89 (0.70-1.20) |

| PIVKA-II (mAU/mL) | 492.8 (106.6-4284.8) |

| Alpha-fetoprotein (ng/mL) | 6.0 (3.6-10.0) |

| Elevated PIVKA-II levels | 97 (85.8) |

| PIVKA-II levels ≥ 400 | 62 (54.8) |

| PIVKA-II levels ≥ 4000 | 16 (14.2) |

| Child Class | |

| A | 38 (33.6) |

| B | 56 (49.6) |

| C | 19 (16.8) |

| Decompensated liver disease (ascites or encephalopathy) | 71 (62.8) |

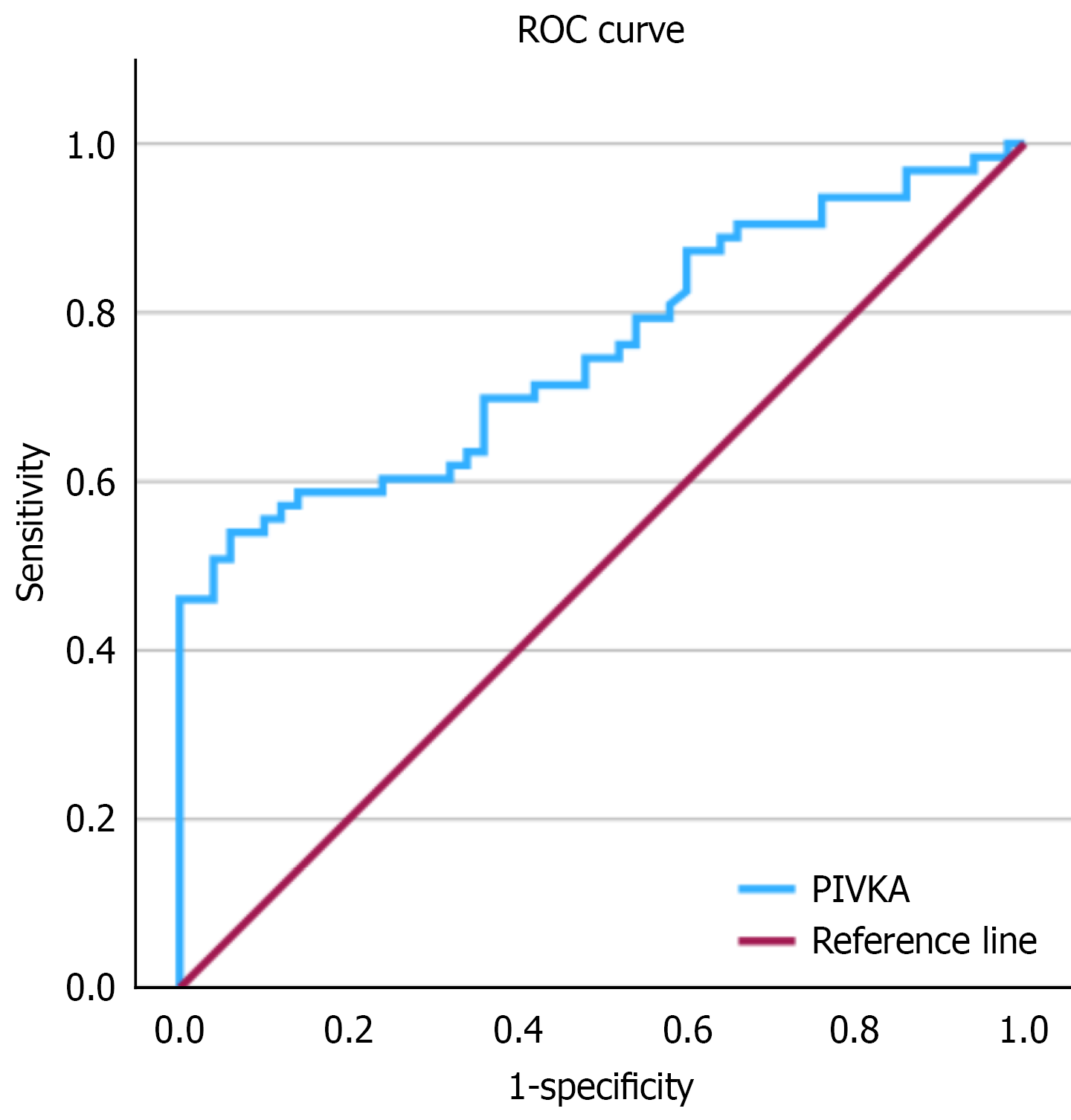

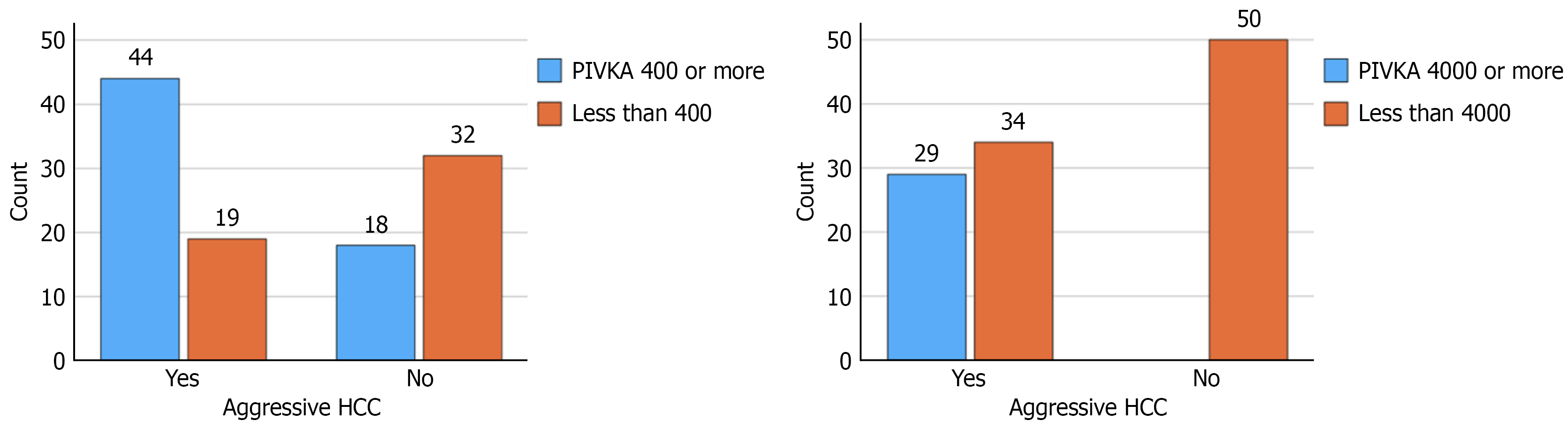

ROC curve analysis for PIVKA-II value for aggressive tumors revealed an area under the ROC curve of 0.756 (SE: 0.045; 95% confidence interval: 0.669-0.844; P < 0.001) (Figure 2). The Youden-optimized cut-off was 1609.5 mAU/mL, yielding sensitivity 0.54 and specificity 0.94; corresponding precision [positive predictive value (PPV)] on the precision-recall curve was 0.919. Given the aim to prioritize sensitivity while maintaining reasonable specificity, we selected a pragmatic threshold of 400 mAU/mL. with a sensitivity 0.69 and specificity 0.64 (PPV: 0.71). At a high-stringency threshold of 4000 mAU/mL (n = 29), precision was 1.00 with recall 0.24-0.25 and specificity 1.00, indicating a very specific but insensitive rule (Figure 3). Two-way contingency table analysis for aggressive tumors with PIVKA-II of 4000 or more showed a P value < 0.001 and relative risk with 95% confidence interval of 2.471 (1.929-2.471).

Demographic and etiologic variables (age, sex, hepatitis B virus/hepatitis C virus status), liver function metrics (albumin, international normalized ratio, bilirubin, Child class) and tumor variables were compared for aggressive and non-aggressive tumors. Parameters for aggressive tumors with P-values < 0.1 were hepatitis B etiology (0.080), hepatitis C etiology (0.039), white blood cell count (0.094), platelets count (0.015), serum sodium (0.025), bilirubin (0.039), aspartate transaminase (0.010), alanine transaminase (0.018), alkaline phosphatase (0.004), and PIVKA-II levels > 400 mAU/mL (P < 0.001). In the logistic regression analysis, PIVKA-II > 400 mAU/mL was strongly associated with aggressive tumor phenotype (adjusted odds ratio = 5.16, P = 0.001). Platelet count and alkaline phosphatase showed inverse associations (Table 2). Model calibration was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, which showed no evidence of lack of fit (χ2 = 2.786, df = 8, P = 0.947).

| Variable | Sig | Exp(B) |

| Hepatitis B etiology | 0.083 | 2.977 |

| Hepatitis C etiology | 0.581 | 0.744 |

| White blood cell count (× 109/L) | 0.130 | 1.097 |

| Platelets count (× 109/L) | 0.014 | 0.988 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.264 | 0.929 |

| Aspartate transaminase (IU/L) | 0.311 | 0.994 |

| Alanine transaminase (IU/L) | 0.962 | 1.000 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 0.009 | 0.994 |

| PIVKA-II 400 or more | 0.001 | 5.155 |

Our study emphasizes the need for improved assessment tools for patients with HCC. By evaluating PIVKA-II in patients with normal AFP levels, healthcare providers can gain a better understanding of tumor behavior, which is crucial for treatment planning and patient management[6,11]. This study demonstrates that elevated PIVKA-II levels were a significant predictor of aggressive HCC in normal-AFP patients, aligning with prior evidence linking PIVKA-II to vascular invasion and tumor progression[12]. In a study by Bhatti et al[13] involving 57 patients with microvascular invasion, the combination of AFP ≥ 40 ng/mL plus PIVKA-II ≥ 350 mAU/mL yielded a sensitivity of 69.6%. In another study by the same group, a combination of AFP > 20 ng/mL and PIVKA-II > 1000 mAU/mL predicted 47.1% of HCC recurrences after liver transplant, whereas HCC recurred in 6.1% of patients not meeting this threshold[14]. Our study differed from the above studies as our patients had normal AFP levels. By ROC analysis, the Youden-optimized PIVKA-II cut-off was 1609.5 mAU/mL (sensitivity: 0.54, specificity: 0.94). To prioritize sensitivity while maintaining reasonable specificity, we also considered a pragmatic threshold of 400 mAU/mL (sensitivity: 0.69, specificity: 0.64). Notably, all patients with PIVKA-II ≥ 4000 mAU/mL (n = 29) were in the aggressive group, suggesting this value delineates an ultra-high-risk stratum. However, this finding is exploratory and limited by sample size and prevalence.

Currently, PIVKA-II is not widely included in most HCC management guidelines. While American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidelines omit PIVKA-II for screening, Japanese protocols endorse its combined use with AFP[15]. In light of our findings, PIVKA-II could be adopted alongside AFP in risk stratification protocols for HCC, particularly in patients with normal AFP, where it fills a prognostic gap. Integrating PIVKA-II into practice could improve risk assessment and guide management decisions, potentially leading to better patient outcomes. Understanding the role of PIVKA-II in predicting tumor aggressiveness allows for more tailored treatment strategies. For instance, patients with elevated PIVKA-II levels, despite normal AFP, may require more aggressive treatment approaches or closer monitoring to manage the risk of recurrence and improve survival rates[16]. Post-treatment PIVKA-II dynamics (e.g., decline after resection) may predict recurrence, as shown in longitudinal studies[17-20].

The strength of this study is that it focuses on AFP-negative HCC. Unlike many earlier studies that included all HCC patients, our normal AFP cohort allowed us to highlight the subset of patients for whom AFP fails to flag risk. This population is underrepresented in guidelines. Our patients had diverse liver disease etiologies and both early and advanced tumor stages, which improves the applicability of our findings to general HCC populations, albeit still needing external validation. Patients with HCC exceeding Milan criteria and those with PVTT are often excluded from transplant lists due to their aggressive nature. Biomarker-based assessments (including PIVKA-II) might one day be used to refine transplant eligibility; for instance, distinguishing patients who, despite large tumors, have indolent tumor biology and could benefit from transplant, as opposed to those with aggressive biology where transplant would be futile.

The limitations of this study are the retrospective design, relatively small sample size, single-center cohort, and lack of longitudinal PIVKA-II measurements to assess dynamic changes. Because we only included patients who had PIVKA-II measured, there may be an inherent selection bias; clinicians might have ordered PIVKA-II in cases they suspected to be high-risk, potentially enriching our cohort with aggressive cases. Our definition of ‘aggressive tumor’ is partly based on tumor size and number (Milan criteria) or vascular invasion, which is inherently correlated with PIVKA-II levels. This relationship might inflate the predictive performance of PIVKA-II for our endpoint. However, it’s noteworthy that PIVKA-II identified this aggressive phenotype even in normal-AFP patients, supporting its utility.

Our findings open avenues for further research into the role of PIVKA-II in HCC. While AFP is a traditional marker for assessing HCC aggressiveness, its limitations in patients with normal levels necessitate the exploration of alternative biomarkers. Prospective trials could test whether incorporating PIVKA-II into HCC surveillance or treatment allocation improves outcomes. By incorporating PIVKA-II into evaluation, clinicians might identify certain patients with traditionally ‘aggressive’ tumors who could still benefit from transplant, for example, those beyond Milan criteria but with low biomarker levels suggesting less aggressive biology. Monitoring PIVKA-II after curative treatment (resection/ablation) in AFP-negative patients might help predict recurrence. This could provide additional insights into the behavior of HCC.

In HCC patients with normal AFP, elevated PIVKA-II levels (especially ≥ 400 mAU/mL) are strongly associated with aggressive tumor characteristics. Incorporating PIVKA-II into risk assessments could improve prognostication and guide management, such as transplant eligibility and adjuvant therapy decisions. Our findings support including PIVKA-II alongside AFP in HCC workups, but prospective multi-center studies are warranted to validate the cutoff values and refine their clinical use.

| 1. | Ganesan P, Kulik LM. Hepatocellular Carcinoma: New Developments. Clin Liver Dis. 2023;27:85-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 98.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Galle PR, Foerster F, Kudo M, Chan SL, Llovet JM, Qin S, Schelman WR, Chintharlapalli S, Abada PB, Sherman M, Zhu AX. Biology and significance of alpha-fetoprotein in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2019;39:2214-2229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 436] [Article Influence: 62.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Han LL, Lv Y, Guo H, Ruan ZP, Nan KJ. Implications of biomarkers in human hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis and therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10249-10261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Poté N, Cauchy F, Albuquerque M, Voitot H, Belghiti J, Castera L, Puy H, Bedossa P, Paradis V. Performance of PIVKA-II for early hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis and prediction of microvascular invasion. J Hepatol. 2015;62:848-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 5. | Liebman HA, Furie BC, Tong MJ, Blanchard RA, Lo KJ, Lee SD, Coleman MS, Furie B. Des-gamma-carboxy (abnormal) prothrombin as a serum marker of primary hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1427-1431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 395] [Cited by in RCA: 432] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (16)] |

| 6. | Liu Z, Wu M, Lin D, Li N. Des-gamma-carboxyprothrombin is a favorable biomarker for the early diagnosis of alfa-fetoprotein-negative hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. J Int Med Res. 2020;48:300060520902575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Inagaki Y, Tang W, Xu H, Wang F, Nakata M, Sugawara Y, Kokudo N. Des-gamma-carboxyprothrombin: clinical effectiveness and biochemical importance. Biosci Trends. 2008;2:53-60. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Heimbach JK, Kulik LM, Finn RS, Sirlin CB, Abecassis MM, Roberts LR, Zhu AX, Murad MH, Marrero JA. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2018;67:358-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2107] [Cited by in RCA: 3143] [Article Influence: 392.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 9. | Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, Montalto F, Ammatuna M, Morabito A, Gennari L. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:693-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5110] [Cited by in RCA: 5388] [Article Influence: 179.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 10. | Saeki I, Yamasaki T, Tanabe N, Iwamoto T, Matsumoto T, Urata Y, Hidaka I, Ishikawa T, Takami T, Yamamoto N, Uchida K, Terai S, Sakaida I. A new therapeutic assessment score for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients receiving hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Suttichaimongkol T, Mitpracha M, Tangvoraphonkchai K, Sadee P, Sawanyawisuth K, Sukeepaisarnjaroen W. PIVKA-II or AFP has better diagnostic properties for hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis in high-risk patients. J Circ Biomark. 2023;12:12-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Si YQ, Wang XQ, Fan G, Wang CY, Zheng YW, Song X, Pan CC, Chu FL, Liu ZF, Lu BR, Lu ZM. Value of AFP and PIVKA-II in diagnosis of HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma and prediction of vascular invasion and tumor differentiation. Infect Agent Cancer. 2020;15:70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bhatti ABHH, Naz K, Abbas G, Khan NY, Zia HH, Ahmed IN. Clinical Utility of Protein Induced by Vitamin K Absence-II in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2021;22:1731-1736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bhatti ABH, Shafique U, Ahmed N, Abbas G, Atiq M, Zia HH, Khan NY, Rana A. Prothrombin-induced by vitamin K absence II as a prognostic factor in living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2025;15:21900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kudo M, Kawamura Y, Hasegawa K, Tateishi R, Kariyama K, Shiina S, Toyoda H, Imai Y, Hiraoka A, Ikeda M, Izumi N, Moriguchi M, Ogasawara S, Minami Y, Ueshima K, Murakami T, Miyayama S, Nakashima O, Yano H, Sakamoto M, Hatano E, Shimada M, Kokudo N, Mochida S, Takehara T. Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Japan: JSH Consensus Statements and Recommendations 2021 Update. Liver Cancer. 2021;10:181-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 523] [Article Influence: 104.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lai Q, Iesari S, Levi Sandri GB, Lerut J. Des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin in hepatocellular cancer patients waiting for liver transplant: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Biol Markers. 2017;32:e370-e374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhu W, Wang W, Zheng W, Chen X, Wang X, Xie J, Jiang S, Chen H, Zhu S, Xue P, Jiang X, Li H, Wang G. Diagnostic performance of PIVKA-II in identifying recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma following curative resection: a retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep. 2024;14:8416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sun H, Yang W, Zhou W, Zhou C, Liu S, Shi H, Tian W. Prognostic value of des-γ-carboxyprothrombin in patients with AFP-negative HCC treated with TACE. Oncol Lett. 2023;25:69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Devillers MJC, Pluimers JKF, van Hooff MC, Doukas M, Polak WG, de Man RA, Sonneveld MJ, Boonstra A, den Hoed CM. The Role of PIVKA-II as a Predictor of Early Hepatocellular Carcinoma Recurrence-Free Survival after Liver Transplantation in a Low Alpha-Fetoprotein Population. Cancers (Basel). 2023;16:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chen J, Wu G, Li Y. Evaluation of Serum Des-Gamma-Carboxy Prothrombin for the Diagnosis of Hepatitis B Virus-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Meta-Analysis. Dis Markers. 2018;2018:8906023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/