Published online Jan 15, 2026. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v18.i1.114745

Revised: November 10, 2025

Accepted: November 27, 2025

Published online: January 15, 2026

Processing time: 107 Days and 20.8 Hours

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is a type of malignant tumor originating from rhab

This paper reports a special case of an elderly woman whose initial liver puncture biopsy showed pleomorphic RMS. After chemotherapy with the vincristine + doxorubicin + cyclophosphamide regimen, the alpha-fetoprotein level increased significantly. Therefore, a second liver puncture was performed, the pathological result of which was hepatic sarcomatoid carcinoma. Next-generation sequencing revealed MET gene amplification with an average copy number of 9 in the tumor tissue; however, both fluorescence in situ hybridization and immunohistochemical tests were negative for MET amplification. The treatment regimen was adjusted to chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy; however, the disease progressed rapidly, and the overall survival was only 6 months.

By sharing the diagnosis and treatment process of this patient and reviewing the relevant literature, we aim to help clinicians enhance their understanding of two rare diseases, namely pleomorphic RMS and sarcomatoid carcinoma of the liver.

Core Tip: Pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma and hepatic sarcomatoid carcinoma are both rare malignant liver tumors. This case report highlights the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges of rare hepatic malignancies, particularly, the critical im

- Citation: Ma JQ, Wang C, Li SN, Zheng Q, Bai J, Ding CX, Zhang YB. Adult liver rhabdomyosarcoma complicated with sarcomatoid carcinoma: A case report. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2026; 18(1): 114745

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v18/i1/114745.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v18.i1.114745

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is a type of malignant tumor originating from rhabdomyocytes or mesenchymal cells differentiating into rhabdomyocytes. According to the 2020 World Health Organization classification, RMS is divided into four major categories on the basis of pathological and morphological features: Embryonal RMS, alveolar RMS, pleomorphic RMS, and spindle cell/sclerosing RMS[1]. Embryonal and alveolar RMS account for 70%-80% of all RMS, whereas pleomorphic RMS is relatively rare. Embryonal RMS mainly occurs in children under 10 years of age; alveolar RMS is common in adolescents, and pleomorphic RMS predominantly occurs in adults over 40 years of age. RMS primarily occurs in the head and neck, followed by the genitourinary system, trunk, and extremities[2,3]. Primary RMS of the liver is extremely rare, accounting for less than 0.1% of all primary liver malignancies[4]. Hepatic sarcomatoid carcinoma (HSC) is also a rare epithelial malignant tumor originating from the liver; it is characterized by the coexistence of both carcinomatous and sarcomatoid spindle cell components. HSC accounts for 0.5%-3.9% of primary liver malignancies[5]. Therefore, an in-depth understanding of the clinical features of these diseases is essential for early diagnosis and timely treatment.

A 68-year-old woman presented to our hospital on February 27, 2023 with a complaint of upper abdominal distending pain for 2 months.

For over 2 months before her visit, the patient experienced upper abdominal distending pain without an obvious triggering factor, accompanied by decreased appetite and aversion to greasy food. She did not report symptoms such as fever, hematemesis, or melena.

In 2003, she was infected with hepatitis C due to a blood transfusion and took antiviral drugs for half a year.

The patient denied having any personal or family history pertinent to her current presentation.

Physical examination at the time of admission revealed no evident positive signs.

The pre-transfusion test was positive for hepatitis B e-antibody, hepatitis B core antibody, and hepatitis C virus antibody. The liver function test showed the following: Alanine transaminase (ALT), 88 U/L; aspartate transaminase (AST), 167

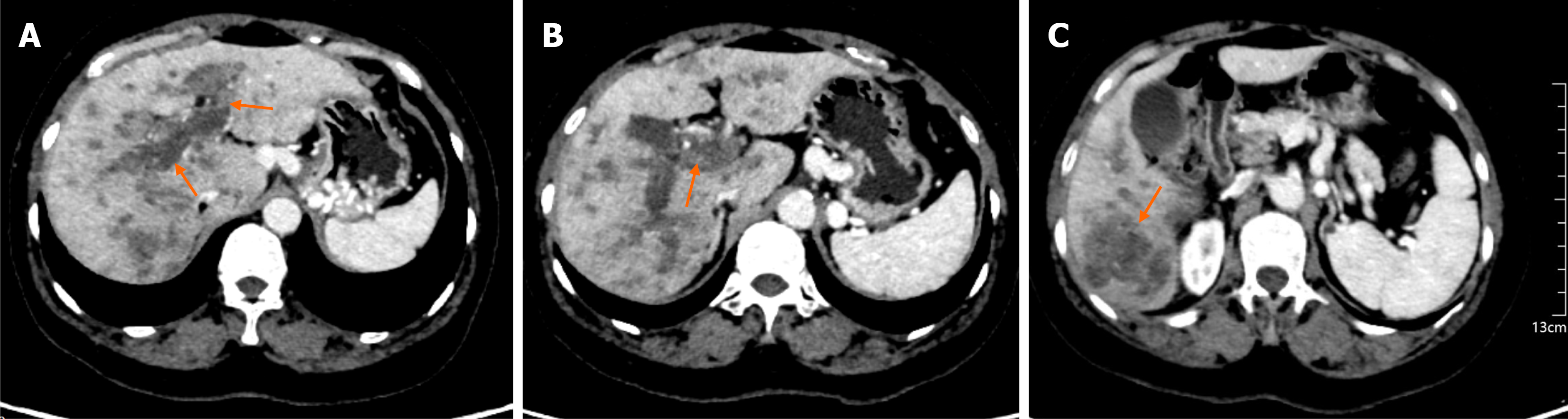

Plain and contrast-enhanced computed tomography: The liver capsule was smooth and morphology was normal. Multiple low-density nodules and masses were seen in the liver, with the largest one measuring approximately 5.1 cm in diameter and having unclear boundaries. After contrast medium injection, they showed heterogeneous enhancement, and some lesions had calcification. The intrahepatic bile ducts were not dilated. Low-density shadows were seen in the main portal vein and its branches. The esophageal-gastric fundus veins and splenic veins were tortuously dilated. The gal

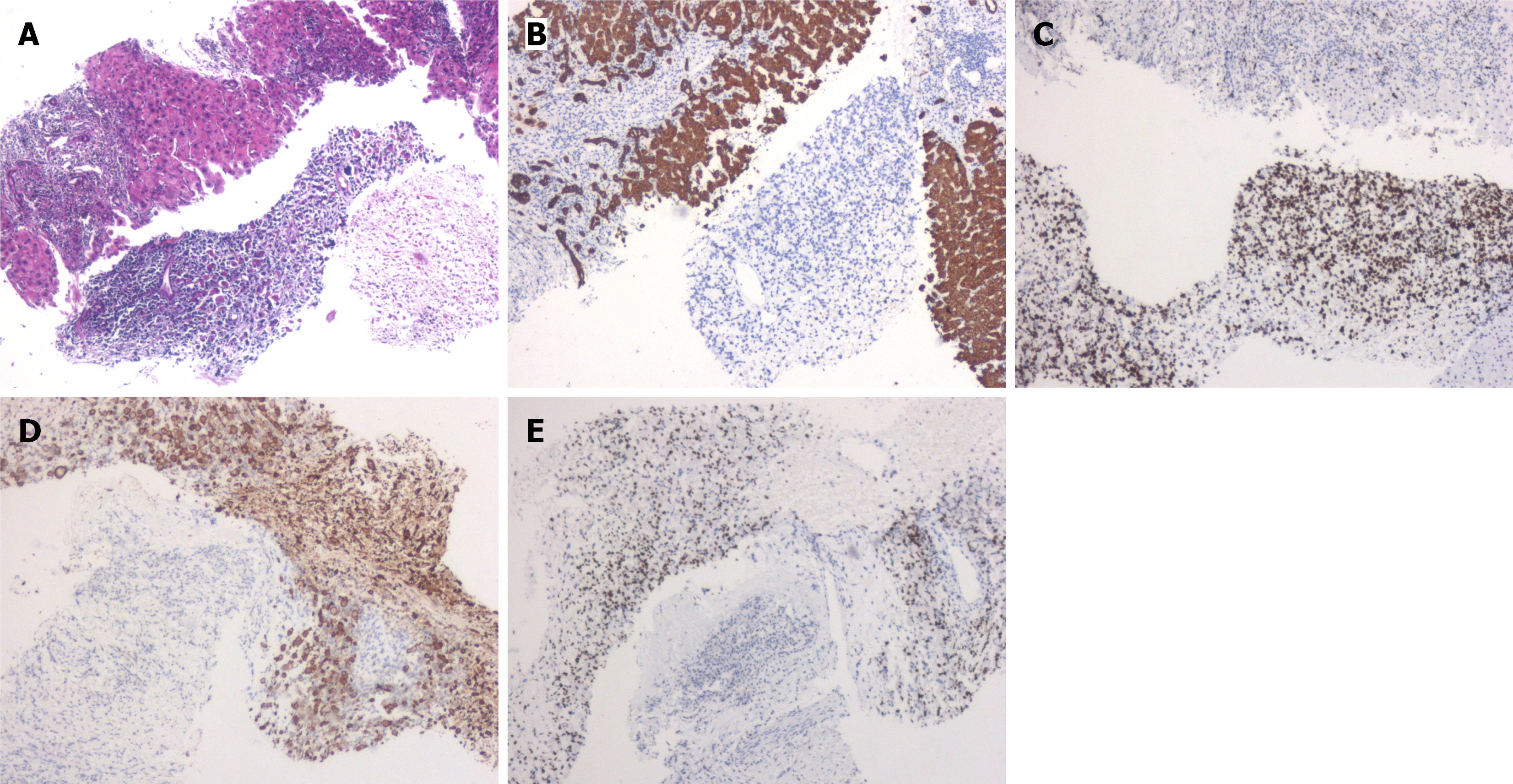

First liver puncture pathology: Histologically, the tumor cells showed evident atypia, with large cell volume, round or polygonal shape, deeply eosinophilic cytoplasm, deformed large cells resembling rhabdomyoblasts, and focal tumor giant cells. Immunohistochemistry showed Ki67 (60%), cytokeratin pan (CKpan) (-), CK8 (-), hepatocyte paraffin 1 (-), S-100 (-), HMB45 (-), desmin (+), and myogenic differentiation 1 (MyoD1) (+). The structure in the “liver” section combined with immunohistochemistry was consistent with pleomorphic RMS (Figure 2).

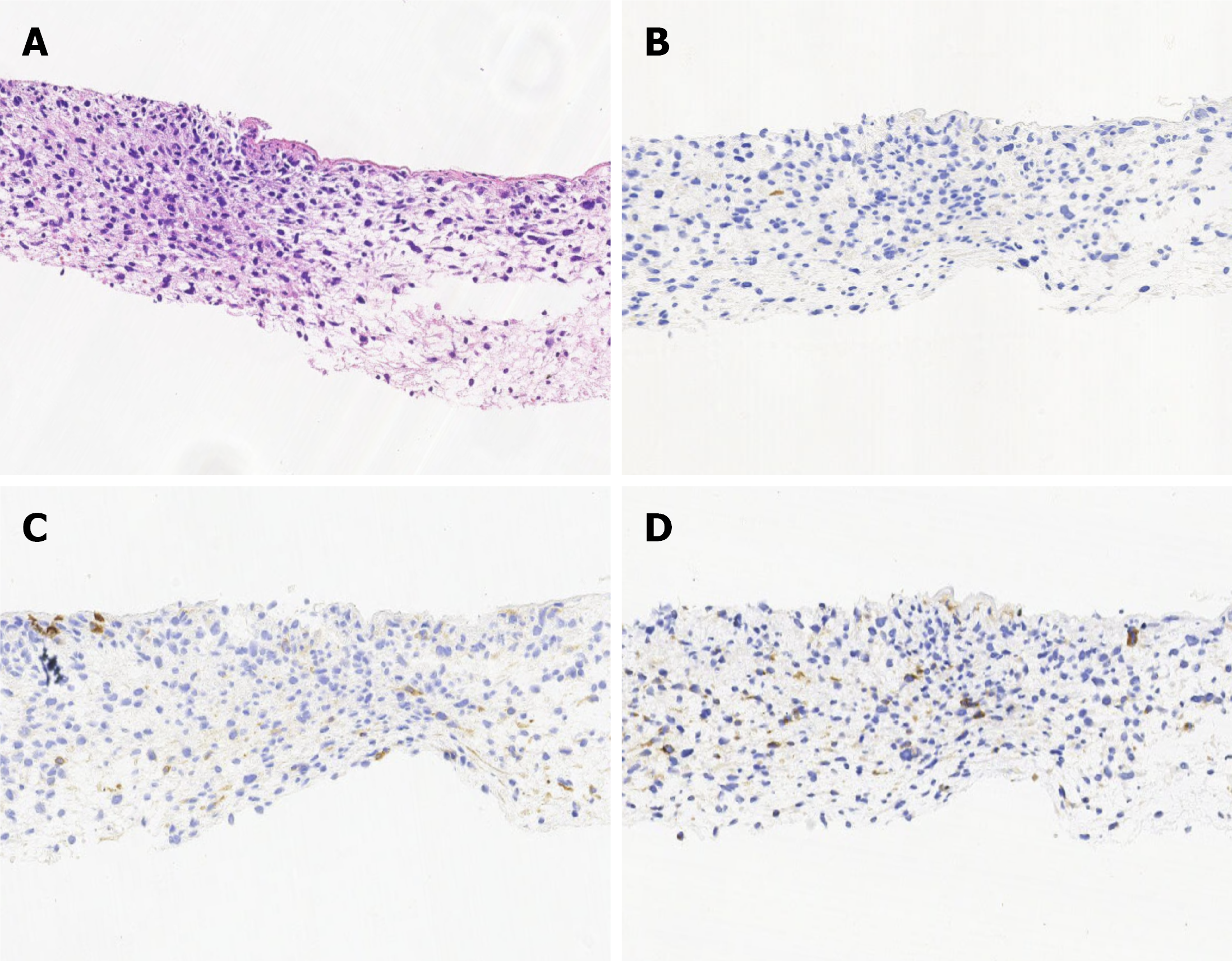

Second liver puncture pathology: Pathological findings showed that most of the tumor cells were spindle-shaped and diffusely arranged, and some local cells were epithelioid. Immunohistochemistry revealed the following: Hepatocyte paraffin 1 (-), glypican-3 (-), Ki-67 (80%), CK7 (-), vimentin (focal +), CK8 (focal +), CK19 (focal +), SMARCA4/BRG1 (+), integrase interactor-1 (+), calretinin-B (membrane +), glutamine synthetase (+), desmin (-), smooth muscle actin (-), MyoD1 (-), and CD34 (vascular +). The structure in the “liver” section, combined with immunohistochemistry, was con

Next-generation sequencing: The result of tissue next-generation sequencing (NGS) showed that the patient had MET amplification (copy number 9), TP53 mutation (L252P, mutation abundance 81%), PDGFRA amplification, RET am

The patient was diagnosed as having a malignant liver tumor (pleomorphic RMS combined with sarcomatoid carcinoma, stage IV) complicated with secondary malignant liver tumors, portal vein cancer emboli, esophageal-gastric fundus varicose veins, and splenic varicose veins. Liver function was classified as Child-Pugh grade B.

After a multidisciplinary consultation, the general surgery and radiotherapy departments found the current liver tumors to be too extensive to be resolved with surgical treatment or local radiotherapy. The interventional department de

To clarify whether the patient had a hepatocellular carcinoma component, a second liver puncture was performed. According to the pathological findings of the second liver puncture and the NGS detection result, the treatment regimen was adjusted to liposomal doxorubicin 40 mg + cisplatin 90 mg + sintilimab 200 mg by intravenous drip for 2 cycles. The AFP level declined from 10150 IU/mL to 3810 IU/mL. The contrast-enhanced CT re-examination performed on July 19, 2024, showed multiple liver masses, and the range of emboli in the main portal vein and its branches was larger than before. The curative effect was evaluated as progressive disease.

The patient died on August 23, 2023, with an overall survival (OS) of 6 months.

Liver RMS is an extremely rare primary malignant tumor of the liver. From 1956 to date, only 34 cases of hepatic RMS have been reported abroad. Since 1995 in China, a total of 13 cases of hepatic RMS have been reported. Table 1 sum

| Case number | Age/sex | Tumor size | Histopathology | Treatment | Follow-up (month) | Outcome |

| 1 | 14/Female | 15.5 cm × 9.5 cm × 12 cm | NA | Heavy dose of X-ray therapy and radiation therapy + total right hepatic lobectomy | NA | NA |

| 2 | 65/Female | 35 cm × 15 cm × 10 cm | Embryonal/alveolar | Untreated | 3 | Death |

| 3 | 76/Male | NA | Embryonal | Untreated | 2 | Death |

| 4 | 70/Male | Multinodular liver tumors | Pleomorphic | Untreated | 8 | Death |

| 5 | 62/Male | 14 cm × 9 cm × 9 cm | NA | Operation + trans-arterial embolisation therapy + chemotherapy | 3 | Death |

| 6 | 1.4/Male | NA | NA | Palliative CA/VD chemotherapy | 15 | Death |

| 2.4/Male | NA | NA | Left hepatectomy + adjuvant CA/VD chemotherapy + radiotherapy | 76 + | Survival | |

| 7/Male | NA | NA | Palliative CA/VD chemotherapy | 8 | Death | |

| 7 | 68/Male | NA | Alveolar | NA | NA | NA |

| 8 | 53/Male | 20 cm | Embryonal | Surgical resection | 3 | Death |

| 9 | 34/Female | 12 cm × 12 cm × 6 cm | NA | Surgery | NA | NA |

| 10 | 69/Male | NA | Pleomorphic | NA | NA | NA |

| 11 | 63/Female | 10 cm × 8 cm × 7 cm | Pleomorphic | Left hepatectomy | 108 | Survival |

| 29/Female | 11 cm | Pleomorphic | Right hepatectomy + adjuvant AI chemotherapy | 180 | Survival | |

| 12 | 52/Male | 19 cm × 12 cm × 11 cm | NA | Untreated | 2 | Death |

| 13 | 8/Male | NA | Pleomorphic | Extended right hepatectomy | 2 | Death |

| 14 | 14/Male | NA | Embryonal | Induction CEV chemotherapy | NA | NA |

| 15 | 59/Female | 6 cm | Alveolar | Left hemi-hepatectomy + palliative AI chemotherapy | 31 | Death |

| 16 | 17/Male | 20 cm × 13 cm | Embryonal | Palliative VCD, MAID, gemcitabine-paclitaxel chemotherapy | 31 | Death |

| 17 | 67/Male | 14.5 cm × 12.3 cm × 9.1 cm | Embryonal | Left hepatectomy + adjuvant AIV chemotherapy | 24 | Survival |

| 18 | 40/Male | 4.5 cm × 4 cm × 4 cm | Embryonal | Hepatic left lateral lobectomy | NA | NA |

| 19 | 66/Female | 20 cm × 15 cm | Pleomorphic | Right hepatectomy | 5 | Death |

| 20 | 57/Female | 18.5 cm | Spindle cell/sclerosing | Partial hepatectomy + adjuvant VCD/IE chemotherapy | 12 | Survival |

| 21 | 73/Female | 12 cm × 10 cm | Pleomorphic | Right hepatectomy + palliative trabectedin chemotherapy | 6 | Death |

| 22 | 5/Female | Diffuse lesions | Embryonal | Induction VCD/VI chemotherapy + SIRT with yttrium-90 + EBRT + palliative VIE chemotherapy | 29 | Death |

| 23 | 7/Male | 7.5 cm × 7.3 cm × 7.7 cm | Embryonal | Neoadjuvant VIE chemotherapy + left hepatectomy + prophylactic radiotherapy + adjuvant VIE chemotherapy | 38 | Survival |

| 24 | 71/Male | 5.6 cm | Epithelioid | Untreated | 12 | Death |

| 25 | 60/Female | 8 cm × 7 cm × 6 cm | Pleomorphic | Neoadjuvant IVAD chemotherapy + right hepatectomy + adjuvant IVAD chemotherapy | 12 | Survival |

| 26 | 15/Male | 15.3 cm × 15.6 cm × 16 cm | Embryonal | Neoadjuvant AI chemotherapy + right extended hepatectomy + adjuvant AI chemotherapy | 36 | Survival |

| 27 | 1.4/Female | 9.4 cm × 9 cm × 11 cm | NA | Neoadjuvant VCD chemotherapy + left hepatectomy + IMRT + adjuvant VCD chemotherapy | 48 | Survival |

The imaging findings of hepatic RMS are non-specific. The tumor is typically solitary, with a diameter of 4.5-35 cm (average diameter, 14 cm). It is round or oval; its interior is prone to bleeding and necrosis, and it typically shows uneven enhancement on enhanced CT scans[8]. Owing to its large size, the most common symptom is upper abdominal pain or discomfort, which may be accompanied by abdominal distension, fatigue, poor appetite, nausea, and fever. Since primary hepatic RMS does not invade the biliary tract, jaundice does not usually occur. Laboratory tests may show a mild increase in lactate dehydrogenase, and liver function indicators are generally within the normal range, as is the AFP level.

Given the non-specificity of imaging, symptoms, and laboratory tests, pathological diagnosis is the gold standard for hepatic RMS. Under the microscope, the tumor cells of hepatic pleomorphic RMS appear polygonal, round, and spindle-shaped, showing skeletal muscle differentiation without embryonic or alveolar components. In most cases, varying numbers of pleomorphic rhabdomyoblasts can be seen, which are large cells with significant atypia, abundant and deeply eosinophilic cytoplasm, no cross-striations, and large pleomorphic nuclei. Immunohistochemistry shows diffuse ex

Surgical resection is the most preferred treatment method to improve the prognosis of patients with hepatic RMS[10,11]. The average survival time of patients who undergo surgery is 16.7 months, whereas that of those who do not receive surgical treatment is only 9.5 months[12]. Surgical methods include anatomical hepatectomy (left/right hemi-hepa

In our case, the patient was an elderly woman with a complaint of upper abdominal pain. The first puncture biopsy showed rhabdomyoblasts under the microscope, characterized by evident atypia, large cell volume, round or polygonal shape, deeply eosinophilic cytoplasm, and deformed large cells. The immunohistochemistry was positive for the skeletal muscle differentiation markers desmin and MyoD1 but negative for the epithelial markers CKpan, CK8, and Hepa. Based on the morphological features and immunohistochemical markers, the diagnosis of PRMS was clear. Following mul

HSC is also a rare epithelial malignant tumor originating from the liver. Its biological behavior is highly invasive and its prognosis is extremely poor. HSC predominantly occurs in middle-aged and elderly people and is more common in males, and it has an average onset age of approximately 50 years. Currently, the pathogenesis of HSC is not fully un

The clinical manifestations and imaging findings of HSC also lack characteristic features. Patients may present with symptoms like abdominal pain, abdominal distension discomfort, jaundice, and fever[17]. The levels of serum tumor markers, such as AFP, CEA, and CA125, may be mildly elevated. Enhanced CT scanning shows a massive mass with a peripheral-to-central filling enhancement pattern or continuous enhancement of the peripheral solid component[18].

The pathological characteristic of HSC is the presence of varying degrees of trabecular pattern transition between the sarcomatoid and ordinary hepatocellular carcinoma areas. The hepatocellular carcinoma area can present a trabecular, nested, or pseudo-glandular structure, and the sarcomatoid area is typically composed of spindle cells arranged in an interlacing bundle pattern. Immunohistochemistry shows positive expression of both epithelial tumor markers (CKpan, keratin, and epithelial membrane antigen) and mesenchymal tumor markers (vimentin and smooth muscle actin). Intermediate keratins, namely CAM5.2, CK8, CK18, and CK19, may also be positively expressed[19]. In our patient, the second puncture biopsy showed spindle-shaped and diffusely arranged tumor cells, with some local epithelioid cells. These cells were positive for both the mesenchymal marker vimentin and epithelial markers CK8 and CK19 but negative for the skeletal muscle differentiation markers desmin and MyoD1. Therefore, the diagnosis of HSC was made.

The main treatment method for HSC is surgical resection[20], and postoperative adjuvant therapy significantly prolongs DFS in patients with HSC[21]. However, due to the rapid growth of the tumor, it is often in the advanced stage at the time of discovery, and the postoperative recurrence rate is relatively high. The efficacy of radiotherapy, chemo

This case reflects the high heterogeneity of tumors, and based on the pathogenesis, we postulate two potential sce

At the same time, this case reflects the high heterogeneity of tumor genes. The patient’s tissue NGS showed MET gene amplification, with an average copy number of 9; however, FISH was negative for MET amplification. Previous studies by Zhang et al[29] have shown that MET gene amplification is an independent prognostic factor for HSC, and MET gene amplification in HSC is more common in the sarcomatoid area than in the epithelial area. Although this patient’s NGS testing indicated MET amplification, the MET FISH was negative. Given that FISH is the gold standard for detecting MET amplification, we were uncertain about using a MET-TKI, and thus, we did not use it.

In conclusion, both hepatic RMS and HSC are rare hepatic malignant tumors, and their pathogenesis, molecular characteristics, and optimal treatment strategies need further exploration.

The authors sincerely thank the patient for her consent to participate in this study.

| 1. | Choi JH, Ro JY. The 2020 WHO Classification of Tumors of Bone: An Updated Review. Adv Anat Pathol. 2021;28:119-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 45.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dehner CA, Rudzinski ER, Davis JL. Rhabdomyosarcoma: Updates on classification and the necessity of molecular testing beyond immunohistochemistry. Hum Pathol. 2024;147:72-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Agaram NP. Evolving classification of rhabdomyosarcoma. Histopathology. 2022;80:98-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Finney N, Tran T, Hasjim BJ, Jakowatz J, Chiao E, Eng O, Wolf R, Jutric Z, Yamamoto M, Tran TB. Primary sarcoma of the liver: A nationwide analysis of a rare mesenchymal tumor. J Surg Oncol. 2024;129:358-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hu C, Zhao M, Wei Q, Chen Z, Zhao B. Sarcomatoid hepatocellular carcinoma: A case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103:e37641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Schoofs G, Braeye L, Vanheste R, Verswijvel G, Debiec-Rychter M, Sciot R. Hepatic rhabdomyosarcoma in an adult: a rare primary malignant liver tumor. Case report and literature review. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2011;74:576-581. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Akki AS, Harrell DK, Weaver KD, Esnakula AK, Shenoy A. Rare case of spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma in adult liver. Pathology. 2019;51:745-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hayakawa K, Shibata T, Yamashita K, Hamanaka D, Tanigawa N, Urata Y, Hosokawa Y, Suzuki T, Wakata Y. Computed tomography and angiogram of primary hepatic rhabdomyosarcoma: report of two adult cases. Radiat Med. 1990;8:35-39. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Ma Y, Guo LC, Huang S, Yang QQ. [Clinicopathologic analysis of pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma]. Zhongguo Linchuang Yixue. 2024;31:100-105. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Li H, Zhang Y, Pan Y, Hui D, Chen J, Jin Y. Clinicopathological analysis of concomitant hepatic embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma and hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2017;213:1014-1018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Arora A, Jaiswal R, Anand N, Husain N. Primary embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the liver. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2016218292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Li X, Li X, Yang DF, Li M, Xu HQ, Zheng S, Gao PJ. Case Report: Pediatric Hepatic Rhabdomyosarcoma With Maximum Lifetime. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:858219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Brimo Alsaman MZ, Ghanem R, Nahas MA, Chatty EM, Hasan HA, Othman ZN, Horoub R. Successful management strategy for giant primary hepatic rhabdomyosarcoma in 15-year-old male: a case report. J Surg Case Rep. 2024;2024:rjad707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Niharika VS, Patkar S, Pai T, Qureshi S. Primary Liver Rhabdomyosarcoma with Burnt-out Paravertebral Disease. Indian J Pediatr. 2025;92:402-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Patel R, Roberson J, Prakash D, Meyer R, Hogan L, Azmy C, Suprenant V, Ryu S, Stessin A. Potential alternative treatment approach for pediatric patient with diffusely infiltrative primary rhabdomyosarcoma of the liver. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2021;26:143-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jia B, Xia P, Dong J, Feng W, Wang W, Liu E, Jiang G, Qin Y. Genetic testing and prognosis of sarcomatoid hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1086908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ma S, Li C, Ma Y, Wang X, Zhang D, Lu Z. A retrospective study on the clinical and pathological features of hepatic sarcomatoid carcinoma: Fourteen cases of a rare tumor. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e30005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | He G, Huang W, Zhou Z, Wu H, Tian Q, Tan L, Li X. Dynamic contrast-enhanced CT and clinical features of sarcomatoid hepatocellular carcinoma. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2023;48:3091-3100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yu MX, Lin XC, Xu DY, Sun GZ. [Sarcomatoid Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Case Report]. Wenzhou Yike Daxue Xuebao. 2021;51:72-74. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Dai Y, Xu M. Hepatic sarcomatoid carcinoma: A case report and literature review. Asian J Surg. 2024;47:2954-2955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ji J, Hu D, Wang J, Qiu G, Wang H, Huang J. Prognostic impact of adjuvant therapy following surgical resection in primary hepatic sarcomatoid carcinoma: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2025;111:8621-8625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wu L, Tsilimigras DI, Farooq A, Hyer JM, Merath K, Paredes AZ, Mehta R, Sahara K, Shen F, Pawlik TM. Management and outcomes among patients with sarcomatoid hepatocellular carcinoma: A population-based analysis. Cancer. 2019;125:3767-3775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Liao SH, Su TH, Jeng YM, Liang PC, Chen DS, Chen CH, Kao JH. Clinical Manifestations and Outcomes of Patients with Sarcomatoid Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology. 2019;69:209-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Queiroz MM, Munhoz RR, Masotti C, Souza LM, Lima LGCA, Asprino PF, Begnami MDFS, Camargo AA, Bettoni F. Durable Response to Nivolumab in a Patient With Hepatic Sarcomatoid Carcinoma: Evolutive Characterization of Genomic and Immunohistochemical PD-L1 Expression Findings. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022;6:e2200163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhu SG, Li HB, Yuan ZN, Liu W, Yang Q, Cheng Y, Wang WJ, Wang GY, Li H. Achievement of complete response to nivolumab in a patient with advanced sarcomatoid hepatocellular carcinoma: A case report. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2020;12:1209-1215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Zhao Z, Wang T, Sun Z, Cao X, Zhang X. Primary hepatic carcinosarcoma: a case report with insights from retrospective analysis of clinical characteristics and prognostic factors. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1470419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Liu LI, Ahn E, Studeman K, Campbell K, Lai J. Primary Hepatic Carcinosarcoma Composed of Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Cholangiocarcinoma, Osteosarcoma and Rhabdomyosarcoma With Poor Prognosis. Anticancer Res. 2020;40:2225-2229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Akasofu M, Kawahara E, Kaji K, Nakanishi I. Sarcomatoid hepatocellular-carcinoma showing rhabdomyoblastic differentiation in the adult cirrhotic liver. Virchows Arch. 1999;434:511-515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zhang X, Zhou C, Zhou KQ, Bai QM, Jiang DX, Sujie AKS, Hou YY, Wang Z, Ji Y. [MET gene amplification and its prognostic role in sarcomatoid hepatocellular carcinoma]. Zhongguo Aizheng Zazhi. 2020;30:641-649. [DOI] [Full Text] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/