Published online Jul 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i7.108162

Revised: May 8, 2025

Accepted: June 9, 2025

Published online: July 15, 2025

Processing time: 95 Days and 22.1 Hours

Pseudoachalasia closely mimics the clinical symptoms of idiopathic achalasia in both clinical symptoms and diagnostic findings, including those from high-resolution manometry and barium esophagography. The similarities often lead to misdiagnosis and the delay of appropriate treatment management. Although most malignancy-associated pseudoachalasia cases are attributed to adenocarcinoma at the gastroesophageal junction, pseudoachalasia due to esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) should also be considered. However, the diffuse infiltrative growth patterns that can occur with ESCC can make diagnosis challenging.

We report the case of a 60-year-old man who presented with progressive dysphagia, weight loss, and nocturnal cough. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy, timed barium esophagogram, and high-resolution manometry were conducted. The results of these investigations supported a diagnosis of type II idiopathic achalasia. However, preoperative computed tomography revealed atypical findings, which prompted further evaluation. Repeat endoscopy with magnifying narrow-band imaging identified abnormal mucosal and vascular patterns, and endoscopic ultrasound demonstrated hypoechoic submucosal lesions with involvement of the muscularis propria. Targeted biopsies confirmed moderately differentiated ESCC. Positron emission tomography revealed extensive metastatic disease; therefore, the patient was diagnosed with stage IVB ESCC. Peroral endoscopic myotomy was aborted, and the patient was referred for palliative chemoradiotherapy.

Atypical malignant features should be critically examined. Multimodal tools such as magnifying narrow-band imaging and endoscopic ultrasound are essential for diagnosing pseudoachalasia.

Core Tip: Pseudoachalasia is a rare condition that mimics idiopathic achalasia; therefore, it is frequently misdiagnosed. We report a case of pseudoachalasia caused by diffusely infiltrative esophageal squamous cell carcinoma that was initially misdiagnosed despite conventional imaging and manometric techniques. Magnifying endoscopy and narrow-band imaging and endoscopic ultrasound were essential in identifying subtle malignancy features. This case highlights the importance of maintaining clinical suspicion and utilizing advanced diagnostics to differentiate pseudoachalasia from primary achalasia.

- Citation: He YS, Lee CY, Shieh TY. Pseudoachalasia as first manifestation of a diffusely infiltrative esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: A case report. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(7): 108162

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i7/108162.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i7.108162

Pseudoachalasia, also known as secondary achalasia, was first described in 1947[1]. This rare condition arises from a variety of etiologies, including malignant neoplasms such as gastric or esophageal carcinoma as well as benign disorders such as amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, or postsurgical anatomical alterations[2,3]. Tumor-related pseudoachalasia can occur through four principal mechanisms: Mechanical obstruction, submucosal tumor infiltration, vagal nerve neuropathy, or paraneoplastic syndromes[3].

Pseudoachalasia frequently mimics primary (idiopathic) achalasia; the overlapping symptoms include progressive dysphagia, retrosternal discomfort, regurgitation, and unintentional weight loss. The radiological and physiological findings of these two conditions, such as those observed on timed barium esophagogram (TBE) and high-resolution manometry (HRM), are often indistinguishable, resulting in misdiagnosis and delaying appropriate treatment. In this report, we describe the case of a 60-year-old male with pseudoachalasia secondary to diffusely infiltrative esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), that was initially misdiagnosed as idiopathic achalasia based on clinical and manometric findings.

He had been experiencing progressive dysphagia involving solids and liquids for 6 months.

He reported unintentional weight loss of 6 kg over the same period, accompanied by acid regurgitation and a nocturnal cough.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease and gout.

His social history was notable for chronic alcohol consumption (300 mL of whiskey weekly to biweekly for > 20 years) and long-term tobacco use (approximately one pack per week for > 30 years). His father had a history of hypertension and benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Physical examination of the neck, chest, and abdomen revealed no abnormalities.

Laboratory tests were unremarkable except for elevated uric acid (9.9 mg/dL) and total cholesterol (238 mg/dL). The tumor marker Carcinoembryonic antigen was within the normal range (0.81 ng/mL), while the ESCC antigen was mildly elevated at 7.24 ng/mL (normal limit: ≤ 1.50 ng/mL).

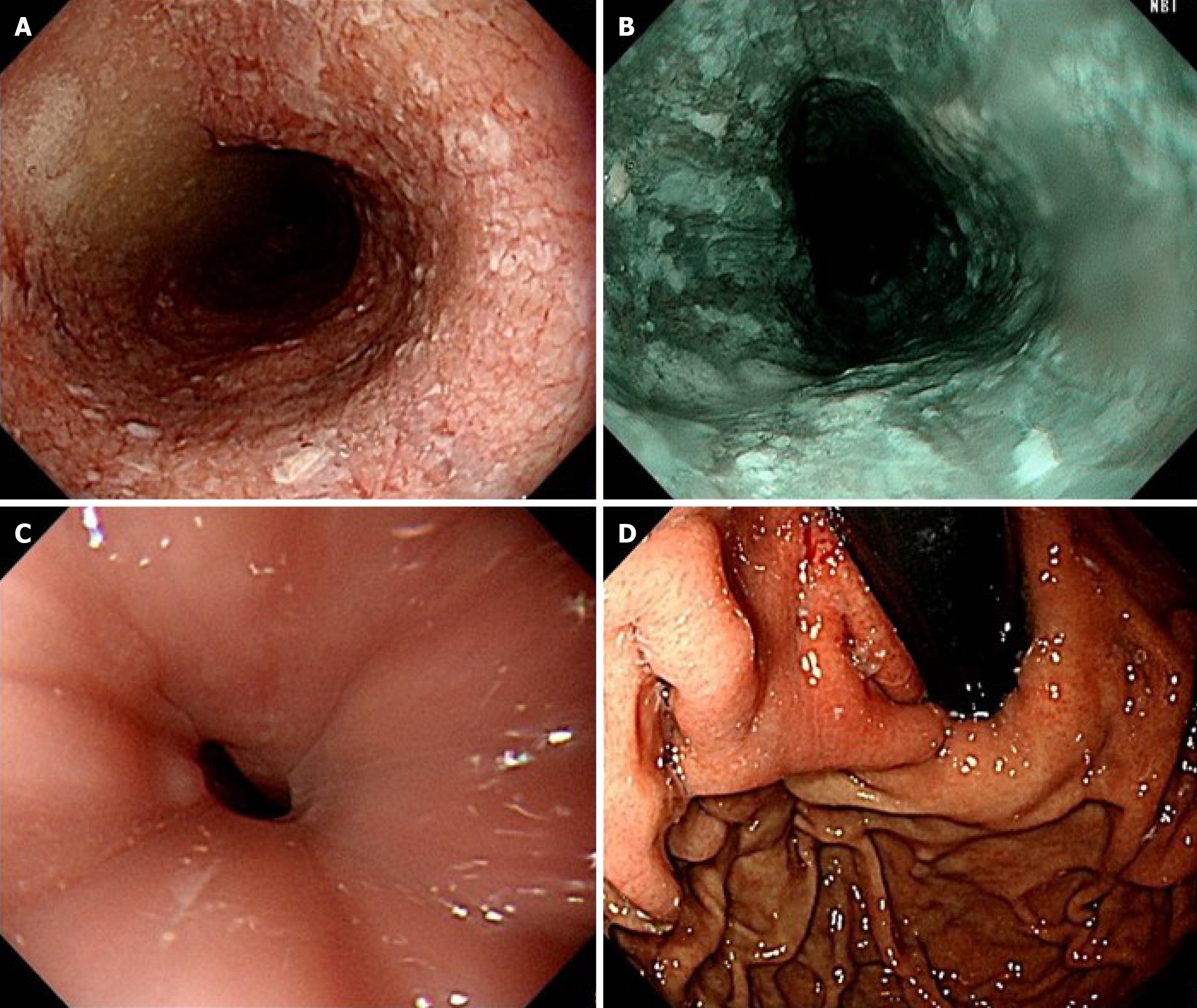

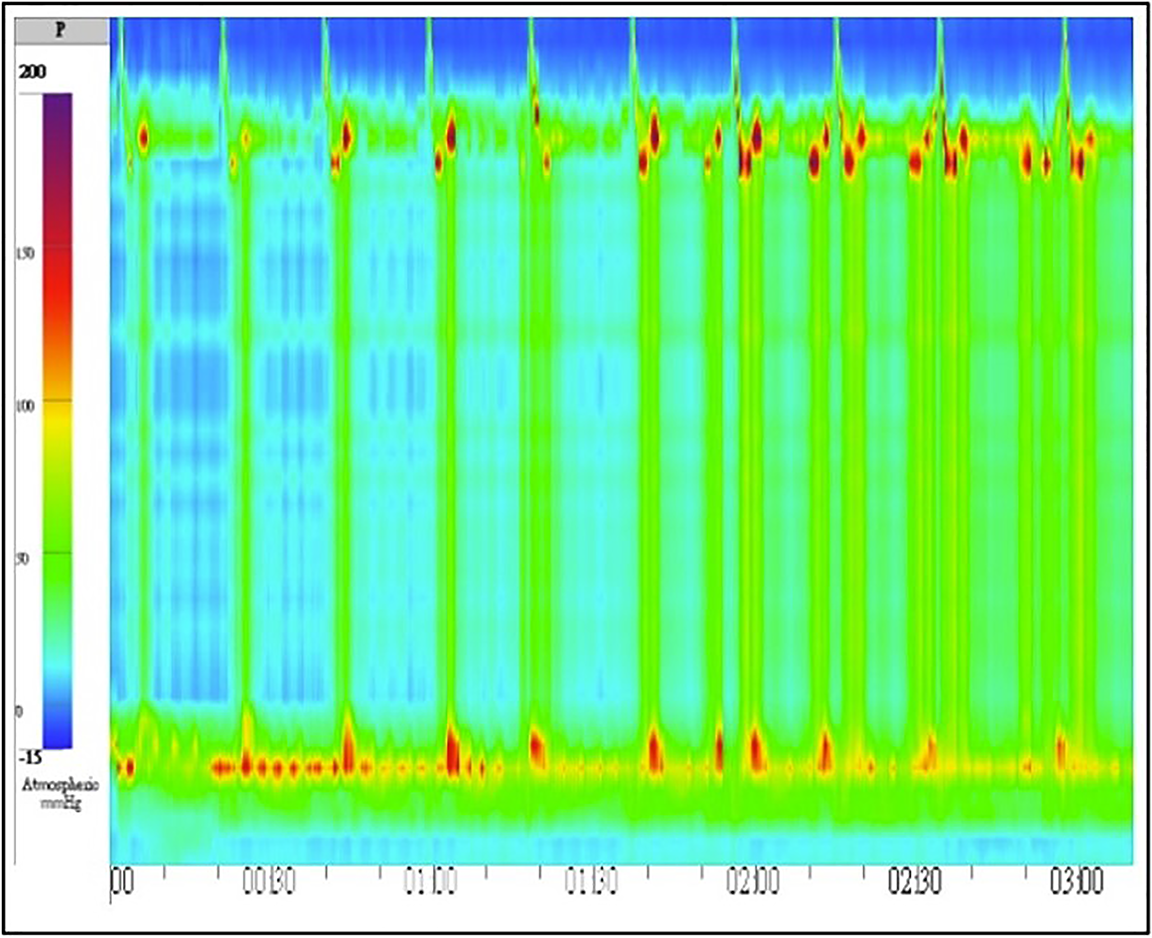

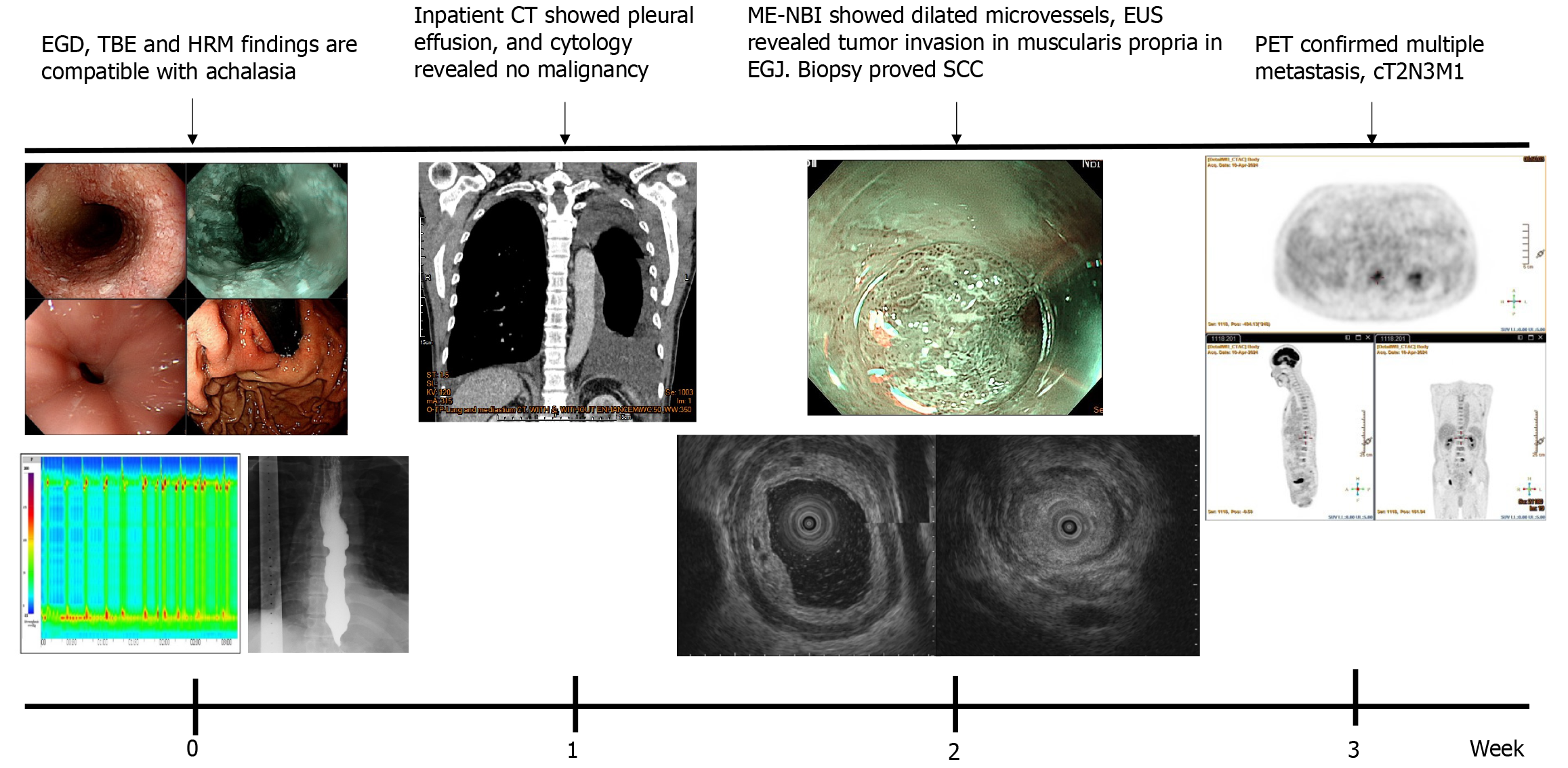

Initial esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed food retention within a markedly dilated esophageal lumen. Significant resistance was encountered during attempted passage of the endoscope through the narrowed esophagogastric junction (EGJ). A retroflexion examination of the gastric cardia revealed no overt masses or mucosal abnormalities (Figure 1). TBE demonstrated the classic “bird-beak” appearance suggestive of achalasia (Figure 2). HRM showed a median integrated relaxation pressure of 68.8 mmHg (normal: < 22 mmHg) with 100% failed peristalsis and panesophageal pressurization, consistent with type II achalasia (Figure 3).

Based on these findings, idiopathic achalasia was diagnosed, and peroral endoscopic myotomy was scheduled for symptomatic relief. However, the routine inpatient chest radiograph showed bilateral pleural effusion. Subsequent computed tomography (CT) revealed bilateral pleural effusion, a diffusely dilated esophagus, and focal wall thickening with luminal narrowing at the EGJ. Thoracentesis was performed; however, cytological analysis of the pleural fluid was negative for malignancy.

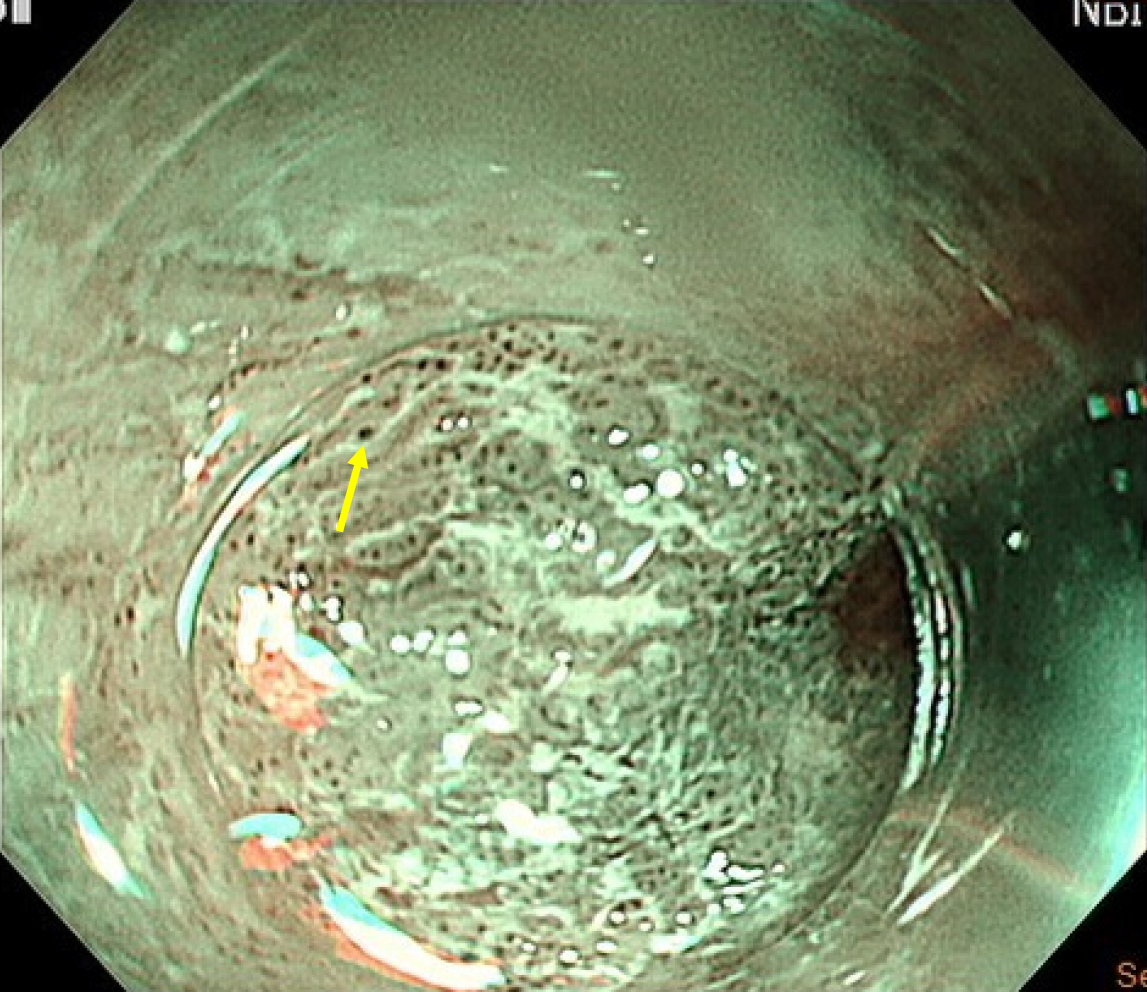

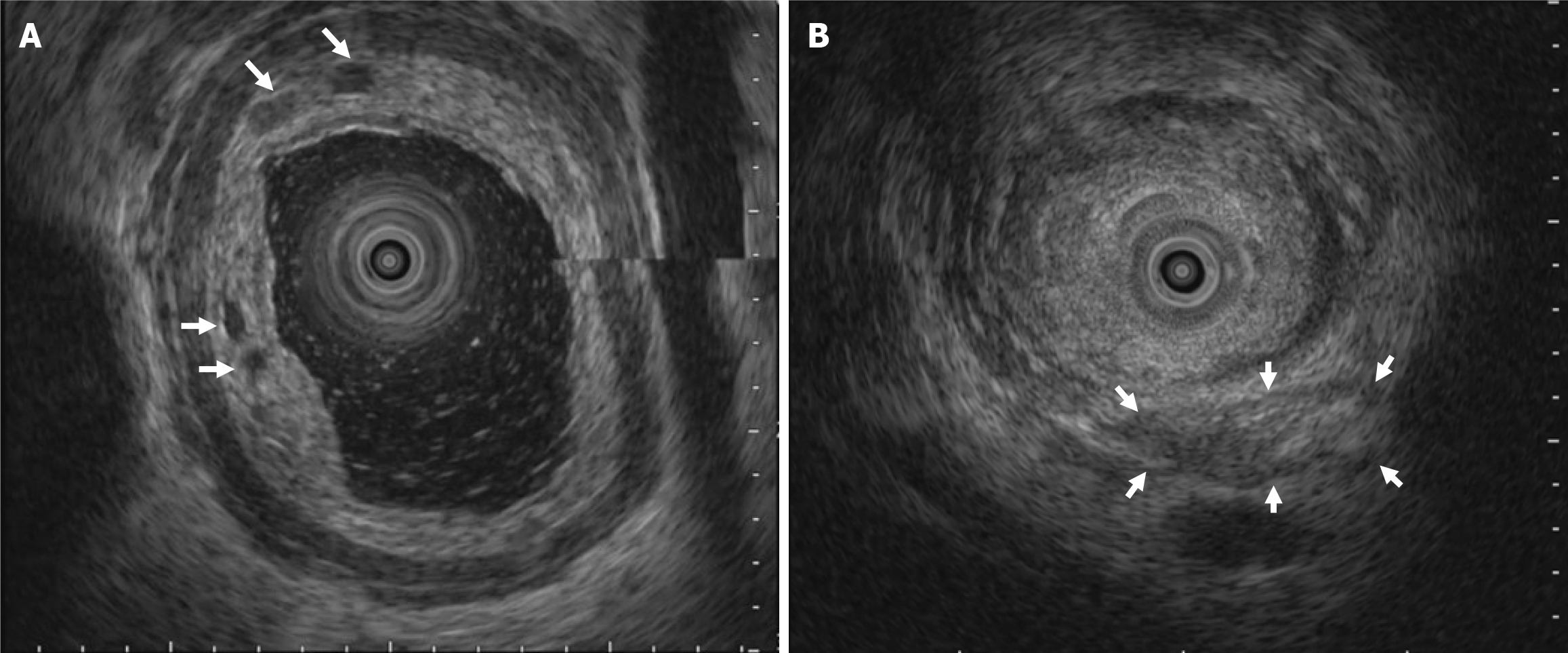

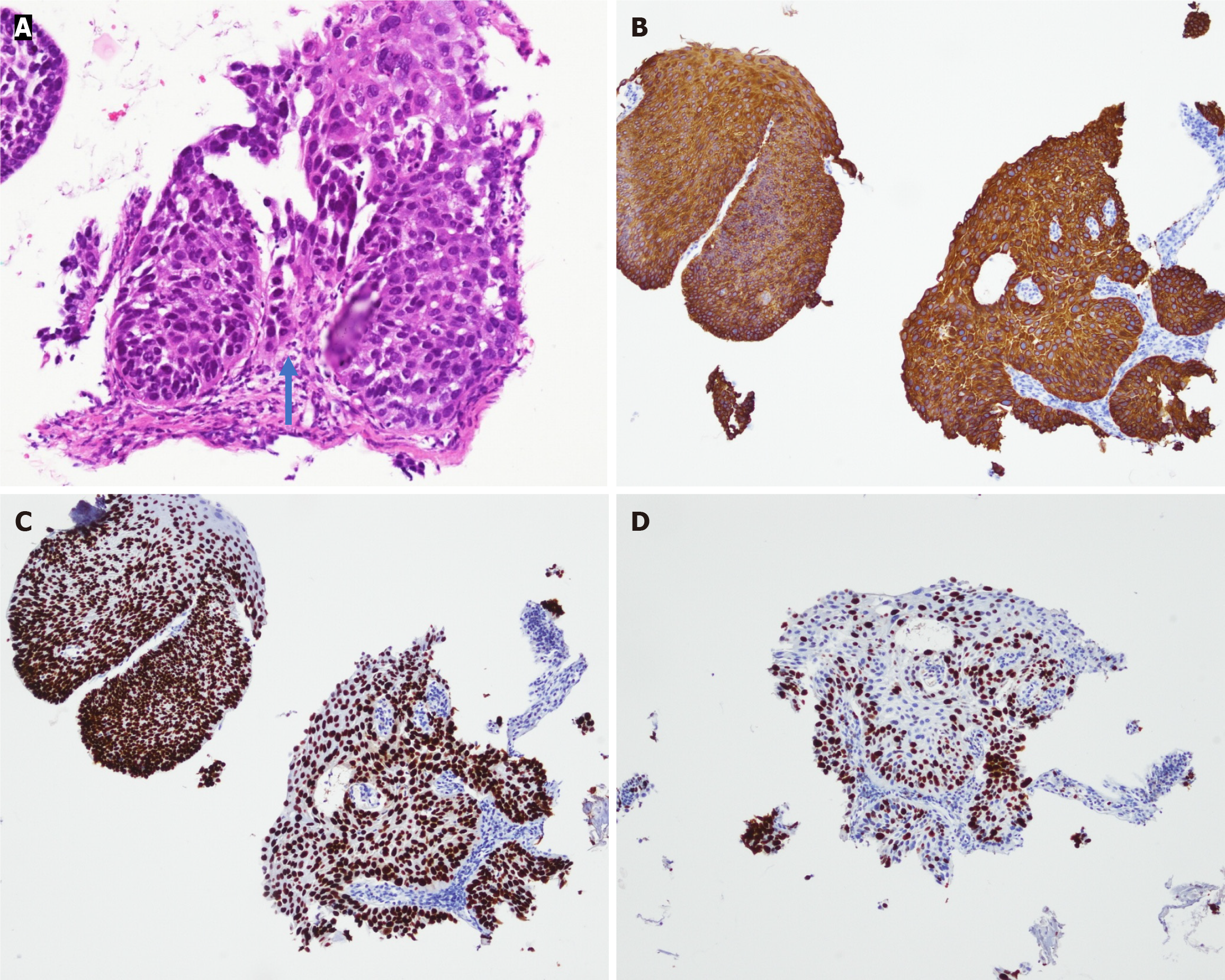

Given these atypical findings, repeat EGD was performed using magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (ME-NBI). This revealed irregular mucosa with abnormal microvascular dilation in the lower esophagus (Figure 4). Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) revealed multiple hypoechoic foci within the submucosal layer, suggestive of tumor infiltration (Figure 5A). Involvement of the muscularis propria at the EGJ was also noted (Figure 5B); this likely accounted for the dysphagia. Owing to concerns about an underlying malignancy, the peroral endoscopic myotomy was aborted. Targeted biopsies of the abnormal mucosa revealed a moderately differentiated ESCC. Immunohistochemical staining showed strong positivity for cytokeratin 5/6 and p63, confirming the squamous lineage. The Ki-67 proliferation index was estimated at approximately 60%, indicating high mitotic activity (Figure 6). No evidence of lymphovascular invasion was identified in the examined tissue specimens. This immunophenotypic profile is consistent with typical patterns observed in ESCC.

Subsequent positron emission tomography confirmed primary ESCC of the lower esophagus with invasion into the muscularis propria, and extensive regional and distant metastases. Metastatic involvement included the supraclavicular, paratracheal, parasternal, pulmonary hilar, and upper abdominal lymph nodes, as well as multiple skeletal sites. The disease was staged as cT2N3M1, corresponding to stage IVB (Figure 7).

The final diagnosis was advanced-stage pseudoachalasia secondary to diffusely infiltrative, moderately differentiated ESCC with multiple bone metastases (cT2N3M1, stage IVB).

The patient was scheduled for a jejunostomy to maintain enteral nutrition, and concurrent chemoradiotherapy was initiated.

The patient was regularly followed up at the outpatient department for nutritional support, monitoring of chemoradiotherapy-related side effects, and assessment of tumor progression.

A comprehensive review of the literature highlights several features distinguishing primary achalasia from pseudoachalasia, as summarized in Table 1[2-4]. These differences are particularly evident in the patient demographics, underlying etiologies, clinical manifestations, and endoscopic findings, all of which influence management strategies and treatment outcomes.

| Characteristic | Achalasia | Pseudoachalasia |

| Age | Average 40-60 years | Average 60 years |

| Gender | Both genders equally | Male predominance (3:2 ratio) |

| Pathophysiology | Inflammation and neuronal degeneration | Mechanical obstruction, submucosal infiltration, or paraneoplastic syndrome |

| Etiology | Unknown, autoimmune, or genetic | Malignancy (e.g., gastric adenocarcinoma); operation |

| Symptoms | Progressive dysphagia, retrosternal pain, regurgitation, weight loss | Similar to achalasia, but shorter symptom duration < 12 months, and often weight loss > 10 kg |

| Esophagogram | Bird’s beak appearance, tram-track sign | Same as with achalasia; irregularities in EGJ, longer narrowed segment (> 3.5 cm) |

| Endoscopy | Food retention, dilated lower esophagus | Food retention, dilated lower esophagus, difficulty in passing the EGJ, nodularity or ulceration |

| Manometry | Impaired LES relaxation, aperistalsis | Similar findings of HRM: Compartmentalized pressurization |

| Computed tomography imaging | Symmetrical wall thickening < 10 mm | Asymmetrical wall thickening > 10 mm, soft-tissue masses at EGJ |

| Management | Pneumatic dilation, botulinum toxin injection, Helle myotomy | Treat malignancy, surgical resection, chemotherapy, radiotherapy |

| Treatment outcome | Often effective in relieving symptoms | Poor prognosis |

Although mucosal biopsy remains the diagnostic gold standard for pseudoachalasia, clinicians must recognize the substantial risk of false negative results, particularly in patients with clinical features suggestive of malignancy. Risk factors that should prompt further evaluation include older age (≥ 55 years), a short symptom duration (≤ 12 months), significant weight loss (≥ 10 kg), and marked resistance to endoscope passage through the EGJ[4].

ME-NBI improves the sensitivity of superficial ESCC detection. A consensus meeting held in Otaru, Japan, in July 2010 endorsed ME-NBI as a valuable tool for the assessment of tumor depth in ESCC, as it allows for the identification of microvascular and mucosal pattern abnormalities that correlate with the depth of invasion[5]. This technique facilitates precise targeting for biopsy, thereby improving the diagnostic yield.

EUS is a critical adjunctive method of evaluating suspected pseudoachalasia, especially in patients with negative or inconclusive standard endoscopy findings. EUS enables high-resolution imaging of the esophageal wall layers and adjacent structures, allowing the detection of subtle submucosal infiltrations not apparent on CT. In cases of pseudoachalasia due to malignancy, EUS may reveal hypoechoic asymmetric thickening infiltrating the surrounding tissues. When combined with fine-needle aspiration, EUS enhances diagnostic accuracy by enabling targeted tissue sampling and facilitating tumor detection and staging[6-8].

Although HRM is widely regarded as the gold standard for diagnosing esophageal motility disorders[9], it lacks specificity in differentiating idiopathic achalasia from malignancy-associated pseudoachalasia[2,8]. Both conditions may exhibit impaired lower esophageal sphincter relaxation and absent peristalsis, resulting in similar HRM patterns. As illustrated in our case, HRM findings alone can be misleading, especially when neoplastic infiltration mimics primary motility disorders. Therefore, clinicians should interpret HRM results with caution in patients presenting with atypical features and should incorporate complementary imaging modalities, such as EUS or enhanced endoscopic techniques, to achieve an accurate diagnosis.

In our patient, despite undergoing EGD, TBE, and HRM - all of which supported the diagnosis of type II achalasia - the final diagnosis was pseudoachalasia. This discrepancy highlights the limitations of conventional diagnostic modalities in detecting underlying malignancies, particularly diffusely infiltrative ESCC of the esophagus[10,11].

One might question why the initial endoscopy failed to detect an esophageal carcinoma. The answer lies in the atypical presentation of the diffusely infiltrative ESCC, which predominantly involved the deeper mucosal and muscular layers. These lesions may appear endoscopically unremarkable under standard white-light imaging, particularly when obscured by retained food and debris. In the current case, subtle mucosal abnormalities and submucosal hypoechoic foci were identified only through the combined application of ME-NBI and EUS, which ultimately confirmed the malignant nature of the lesion and led to a revised diagnosis of pseudoachalasia.

This case illustrates the diagnostic challenges in distinguishing pseudoachalasia from idiopathic achalasia and highlights the limitations of relying solely on conventional imaging and manometric techniques. Although CT was performed, it failed to detect tumor invasion. This is consistent with previous studies in which diagnostic accuracies of 59%-82% were reported[12]. The majority of publications that feature malignancy-associated pseudoachalasia have described cases that were secondary to adenocarcinoma that arose from the gastric cardia[2,3,13]. In contrast, reports on pseudoachalasia caused by ESCC are uncommon.

In the present case, the diffusely infiltrative growth pattern likely contributed to the diagnostic difficulty. Tumors from ESCC often invade the submucosal and muscular layers without forming an obvious mucosal mass, thereby eluding detection by standard endoscopy. This case highlights an uncommon mechanism of pseudoachalasia and underscores the need for a high index of suspicion in patients with atypical clinical features.

Other rare conditions such as Chagas disease, paraneoplastic syndromes, amyloidosis, and sarcoidosis can mimic the clinical and manometric features of achalasia[13]. Although these conditions are less common in non-endemic regions, they should be still considered, particularly in cases with atypical clinical features or inconclusive diagnostic findings. For example, Chagas disease results from infection with Trypanosoma cruzi that leads to myenteric plexus destruction, whereas paraneoplastic pseudoachalasia is typically mediated by autoimmune responses against enteric neurons. A multimodal diagnostic approach remains essential to differentiate these entities and to ensure appropriate management.

In conclusion, clinical suspicion, particularly in patients with atypical presentations or known risk factors for malignancy, should prompt further diagnostic investigations. We advocate the routine use of EUS and image-enhanced endoscopy such as ME-NBI in patients initially diagnosed with achalasia, particularly when malignancy cannot be definitively excluded. This case underscores the need for a comprehensive and multimodal diagnostic approach to prevent misdiagnosis and ensure the timely management of pseudoachalasia secondary to malignancy.

This case underscores the limitations of standard diagnostic tools in differentiating pseudoachalasia from idiopathic achalasia, particularly in malignancies with diffuse infiltrative patterns. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for malignancy in patients with atypical features, such as rapid symptom progression, significant weight loss, and resistance to endoscope passage. A multimodal diagnostic approach - including ME-NBI and EUS - is essential to ensure accurate diagnosis and timely intervention in cases of suspected pseudoachalasia.

| 1. | Ogilvie H. The early diagnosis of cancer of the oesophagus and stomach. Br Med J. 1947;2:405-407. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Schizas D, Theochari NA, Katsaros I, Mylonas KS, Triantafyllou T, Michalinos A, Kamberoglou D, Tsekrekos A, Rouvelas I. Pseudoachalasia: a systematic review of the literature. Esophagus. 2020;17:216-222. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Haj Ali SN, Nguyen NQ, Abu Sneineh AT. Pseudoachalasia: a diagnostic challenge. When to consider and how to manage? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2021;56:747-752. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Ponds FA, van Raath MI, Mohamed SMM, Smout AJPM, Bredenoord AJ. Diagnostic features of malignancy-associated pseudoachalasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:1449-1458. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Uedo N, Fujishiro M, Goda K, Hirasawa D, Kawahara Y, Lee JH, Miyahara R, Morita Y, Singh R, Takeuchi M, Wang S, Yao T. Role of narrow band imaging for diagnosis of early-stage esophagogastric cancer: current consensus of experienced endoscopists in Asia-Pacific region. Dig Endosc. 2011;23 Suppl 1:58-71. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Rampado S, Bocus P, Battaglia G, Ruol A, Portale G, Ancona E. Endoscopic ultrasound: accuracy in staging superficial carcinomas of the esophagus. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:251-256. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Bryant RV, Holloway RH, Nguyen NQ. Education and imaging. Gastrointestinal: Role of endoscopic ultrasound in the evaluation of pseudoachalasia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1128. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Vaezi MF, Pandolfino JE, Vela MF. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1238-49; quiz 1250. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Yadlapati R, Kahrilas PJ, Fox MR, Bredenoord AJ, Prakash Gyawali C, Roman S, Babaei A, Mittal RK, Rommel N, Savarino E, Sifrim D, Smout A, Vaezi MF, Zerbib F, Akiyama J, Bhatia S, Bor S, Carlson DA, Chen JW, Cisternas D, Cock C, Coss-Adame E, de Bortoli N, Defilippi C, Fass R, Ghoshal UC, Gonlachanvit S, Hani A, Hebbard GS, Wook Jung K, Katz P, Katzka DA, Khan A, Kohn GP, Lazarescu A, Lengliner J, Mittal SK, Omari T, Park MI, Penagini R, Pohl D, Richter JE, Serra J, Sweis R, Tack J, Tatum RP, Tutuian R, Vela MF, Wong RK, Wu JC, Xiao Y, Pandolfino JE. Esophageal motility disorders on high-resolution manometry: Chicago classification version 4.0(©). Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33:e14058. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Natsugoe S, Matsushita Y, Kijima F, Tokuda K, Shimada M, Shirao K, Kusano C, Baba M, Yoshinaka H, Fukumoto T, Mueller J, Aikou T. Diffusely infiltrative squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Surg Today. 1998;28:129-134. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Usui A, Akutsu Y, Kano M, Shuto K, Sakata H, Yoneyama Y, Ikeda N, Oide T, Matsubara H. Diffusely infiltrative squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus presenting as a case with diagnostic difficulty. Surg Today. 2013;43:794-799. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Iyer R, Dubrow R. Imaging of esophageal cancer. Cancer Imaging. 2004;4:125-132. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Zanini LYK, Herbella FAM, Velanovich V, Patti MG. Modern insights into the pathophysiology and treatment of pseudoachalasia. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2024;409:65. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |