Published online Apr 15, 2024. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v16.i4.1668

Peer-review started: December 30, 2023

First decision: January 13, 2024

Revised: January 25, 2024

Accepted: February 29, 2024

Article in press: February 29, 2024

Published online: April 15, 2024

Processing time: 102 Days and 7.4 Hours

Primary pancreatic lymphoma (PPL) is an exceedingly rare tumor with limited mention in scientific literature. The clinical manifestations of PPL are often nonspecific, making it challenging to distinguish this disease from other panc

In this case study, we present the clinical details of a 62-year-old woman who initially presented with vomiting, abdominal pain, and dorsal pain. On further evaluation through positron emission tomography-computed tomography, the patient was considered to have a pancreatic head mass. However, subsequent endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) revealed that the patient had pancreatic peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS). There was a substantial decrease in the size of the pancreatic mass after the patient underwent a cycle of chemotherapy comprised of brentuximab vedotin, gemcitabine, and oxaliplatin (brentuximab vedotin and Gemox). The patient had significant improvement in radiological findings at the end of the first cycle.

Primary pancreatic PTCL-NOS is a malignant and heterogeneous lymphoma, in which the clinical manifestations are often nonspecific. It is difficult to diagnose, and the prognosis is poor. Imaging can only be used for auxiliary diagnosis of other diseases. With the help of immunostaining, EUS-FNA could be used to aid in the diagnosis of PPL. After a clear diagnosis, chemotherapy is still the first-line treatment for such patients, and surgical resection is not recommended. A large number of recent studies have shown that the CD30 antibody drug has potential as a therapy for several types of lymphoma. However, identifying new CD30-targeted therapies for different types of lymphoma is urgently needed. In the future, further research on antitumor therapy should be carried out to improve the survival prognosis of such patients.

Core Tip: Primary pancreatic lymphoma is an extremely uncommon tumor with nonspecific clinical symptoms, making it challenging to distinguish this disease from other pancreatic-related diseases. In this case, we present the clinical details of a 62 woman who initially presented with vomiting, abdominal pain, and dorsal discomfort. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration revealed the diagnosis of pancreatic peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified. There was a substantial decrease in the size of the pancreatic mass after the patient underwent a cycle of chemotherapy comprised of brentuximab vedotin, gemcitabine, and oxaliplatin. We have further summarized these illnesses to clarify their etiology.

- Citation: Bai YL, Wang LJ, Luo H, Cui YB, Xu JH, Nan HJ, Yang PY, Niu JW, Shi MY. Primary pancreatic peripheral T-cell lymphoma: A case report. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2024; 16(4): 1668-1675

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v16/i4/1668.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v16.i4.1668

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) is a biologically and clinically heterogeneous disease that accounts for 10%-15% of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma cases but 25%-30% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) in China[1,2]. According to the most recent edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification, more than 30 different clinicopathologic subtypes of PTCL are recognized at present[3,4]. The prognosis is generally dismal for all types of cancer. The most common histological subtype of PTCL, not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS), accounting for 20%-30% of all PTCL cases[2,5]. The wastebasket category of PTCL-NOS exhibits a broad spectrum of immunophenotypic and morphological features. Approximately two-thirds of the types of PTCL can be definitively recognized according to the WHO classification, but these types of T-cell lymphoma cannot be further classified and are often accompanied by poor prognosis[4]. Although any organ can be affected, nodal illness can also impact the bone marrow (22%), liver, spleen, skin, and other organs. Nodal involvement is common upon diagnosis[6].

Only 0.1% of malignant lymphomas, 0.6% of extranodal lymphomas, and 0.2% of all pancreatic malignancies are caused by primary pancreatic lymphoma (PPL)[7,8]. The most prevalent type of PPL is diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), which potentially presents as other lymphomas; however, cases of PTCL-NOS, which are non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and T-cell lymphoma, are even rarer than are other types of PPL[9,10]. Currently, there are no available statistical data on the presence of PPL in PTCL-NOS patients. Pancreatic masses often present with symptoms such as abdominal pain, fever, and vomiting, which are similar to the clinical manifestations of PPL[11]. Therefore, it can be challenging to differentiate PPL from other pancreatic tumors based solely on clinical symptoms. Additional diagnostic tests, such as imaging studies and biopsies, are necessary to accurately diagnose PPL. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) is meaningful not only for the identification of solid tumors but also for treatment[12].

In clinical practice, the differential diagnosis of PPL from other pancreatic tumors are a major problem. However, the treatment methods used for these two diseases are extremely different. Therefore, a clear diagnosis is crucial. In contrast to adenocarcinoma, PPL frequently manifests as a pancreatic tumor greater than 5 cm in length without evidence of vascular involvement[13-15]. No prior reports of PPL involving the PTCL-NOS exist. We propose a case of CD30+ PTCL-NOS with abdominal pain as the first manifestation.

A 62-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with a chief complaint of vomiting, abdominal pain, and dorsal pain that had been aggravated for more than 2 months.

Symptoms started more than 2 months before presentation with lower abdominal pain.

There is no special abnormality in the patient's past medical history.

The patient denied any family history of malignant tumors.

Tenderness and rebound pain were found on the left abdomen, but the peritoneal irritation sign was negative, not accompanied by jaundice and hepatosplenomegaly.

Blood amylase was 181 U/L. Urinary amylase was 4841 U/L. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was 381.2 U/L. No abnormality was found in routine stool, urine analyses, levels of serum tumor markers, liver function, carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9).

Computed tomography (CT) revealed irregular low mixed-density masses in the head of the pancreas, uncinate process, and adjacent abdominal cavity with multiple exudative changes that were malignant. Abdominal color doppler ultrasound confirmed that the head of the pancreas presented a low-echo lesion of approximately 71 mm × 33 mm × 42 mm, and the boundary was not clear. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) revealed irregular and low mixed-density masses in the head of the pancreas and adjacent abdominal cavity. The maximum cross-section length was approximately 51 mm × 41 mm, and the maximal standardized uptake values (SUVmax) was approximately 20.3 (Figure 1).

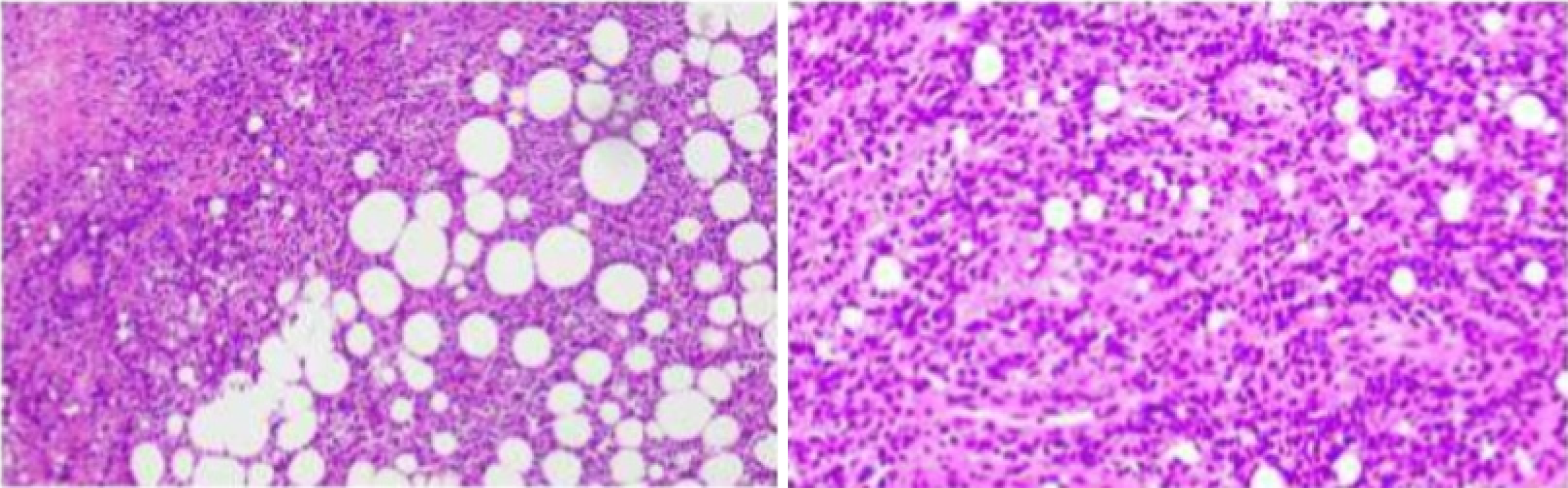

We performed EUS-FNA and successfully obtained biopsy tissue from the pancreatic head. During the EUS-FNA, a mass approximately 8 cm in diameter was found in the head of the pancreas, and the mass had invaded the mesenteric root vessels. Intraoperative frozen sectioning of the pancreatic head revealed that nuclear hyperchromatic heterotypic cells were observed in fibrous connective tissue, and there was a high likelihood of malignancy. Postoperative pathology revealed T-cell-based non-Hodgkin's lymphoma with consideration of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) and CD30+ PTCL (Figures 2 and 3). Based on these pathological results, stained sections were also evaluated independently by six pathologists. Finally, combining the patient's medical history, physical examination, imaging studies, and pathological biopsy, they came to this conclusion: CD30+ PTCL-NOS. Thus, the diagnosis of malignant lymphoma was suspected.

Postoperative pathology via endoscopic ultrasonography-guided FNA (EUS-FNA) revealed small lymphocytes and sporadic atypical tissue cells with pleomorphic vesicular nuclei. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) revealed that the interspersed large atypical lymphoid cells were positive for the pan-T-cell markers CD30, vimentin, CD3, P53, CD2, CD4, CD5, CD34 and TIA-1, with a Ki-67 index of 90%, and negative for ALK, CK, CK7, CD56, SyN, CD20, CD10, CD8, MPO, CD79a, Bcl-6 and EBER. Bone marrow biopsy revealed decreased bone marrow proliferation, and IHC revealed that the interspersed large atypical lymphoid cells were positive for the T-cell markers CD3, CD56, CD20, CD7, CD79a, and TIA-1 and negative for CD30. Flow cytometry revealed a small number of CD3+CD5-T cells. A total of 8 differential genomic variations were obtained by comparing the results of next-generation sequencing, which included ERBB4, STAT3, CARD11, B2M, CXCR4, RELN, CDKN2B and CDKN2A, but no first-order variation was found (Table 1). Based on these histological features and immunophenotypes, a diagnosis of primary pancreatic PTCL-NOS was established. According to Ann Arbor staging, the patients were in the stage III.

| Gene | Transcript | Sequence changes | Amino acid changes | Functional region | Copy frequency/copy coefficient | Variation level |

| ERBB4 | NM_005235.2 | c.3122T>G | p. I1041S | EX25 | 40.6% | III |

| STAT3 | NM_139276.2 | c.1927C>A | p. Q643K | EX21 | 37.0% | III |

| CARD11 | NM_032415.4 | c.2726A>C | p. K909T | EX21 | 35.2% | III |

| B2M | NM_004048.2 | c.2T>C | p. 0? | EX1 | 33.8% | III |

| CXCR4 | NM_003467.2 | c.1000C>T | p. R334* | EX2 | 32.8% | II |

| RELN | NM_005045.3 | c.5331T>G | p. I1777M | EX35 | 32.4% | III |

| CDKN2B | NM_004936.3 | Deficiency | 9p21.3 | 0.3 | III | |

| CDKN2A | NM_000077.4 | Deficiency | 9p21.3 | 0.2 | II |

Finally, the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis was based on the symptoms of upper abdominal pain and imaging. Based on these histological features and immunophenotypes, a diagnosis of primary pancreatic PTCL-NOS (stage III) was established.

After the diagnosis was confirmed, we first administered somatostatin, antibiotics and other symptomatic treatments for the patient's abdominal pain and inflammation, but the effect was relatively poor. We simultaneously carried out multidisciplinary consultations. According to the consultation results, she underwent gastroenterography, which was normal. She subsequently consented to chemotherapy with brentuximab vedotin, gemcitabine, and oxaliplatin combined with total intravenous nutritional support. After the first cycle, the patient's abdominal pain was significantly reduced, but severe vomiting followed, which was considered to be a chemotherapy-related adverse reaction.

Abdominal color doppler ultrasound confirmed that a low-echo lesion of approximately 61 mm × 25 mm × 35 mm was present below the head of the pancreas, with no clear boundary. She had significant improvement in radiological findings at the end of the first cycle. However, 20 d later, imaging showed that the pancreatic tumor had increased in size compared to before. In the subsequent follow-up, the patient's condition deteriorated rapidly and unfortunately passed away due to severe infection caused by intestinal perforation.

Extranodal tissues are involved in up to 40% of cases of NHL, the most common of which involves the gastrointestinal tract[16]. Among NHLs, PTCL accounts for 10% of cases. PTCL-NOS is the most prevalent subtype (26%), followed by angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (19%), ALCL with ALK-positive (7%), and ALCL with ALK-negative (6%)[17]. PPL is an extremely rare lymphoma that accounts for 0.1% of malignant lymphomas and 0.6% of extranodal lymphomas. The PPL specifically affects the pancreas[10,18]. The clinical symptoms of PPL are not consistent, and accurate identification of lesions in other pancreatic tumors is a major problem.

It is difficult to differentiate pancreatic schwannomas from other tumors of the pancreas based only on clinical symptoms, often resulting in diagnostic problems. The clinical manifestations of PPL include the following: Abdominal pain, jaundice, fever, chills, and night sweats, with or without associated lymphadenopathy. Notably, pancreatic PTCL-NOS patients exhibit gastrointestinal-associated symptoms, including stomach discomfort and vomiting, but most PTCL-NOS patients tend to exhibit characteristic B-symptoms, such as fever, weight loss, and night sweats[16,19]. Although PPL causes enlargement of the pancreas due to an infiltrative process in the pancreas, it generally does not cause obstruction of the pancreatic duct. In contrast, malignant pancreatic tumors easily compress the pancreatic duct and lead to obstruction, resulting in a series of clinical symptoms. Another important manifestation is enlarged lymph nodes, which mostly manifest as lymphoma[12,16,17]. With respect to diagnosis, CA19-9 and LDH can assist in the early diagnosis of pancreatic tumors. However, in patients with PPL, these indices are often not elevated or are only slightly elevated except for biliary obstruction. Although researchers are always learning more about the potential function of tumor markers, precise diagnoses are still lacking. Gan et al[12] Performed corresponding research on PPL and indicated that an increase in CA19-9 cannot rule out the diagnosis of lymphoma and that an increase in LDH is not a specific marker of pancreatic tumors.

In our patient, the LDH levels were slightly elevated. In addition, ultrasound, CT, magnetic resonance imaging, etc., can also be used for auxiliary diagnosis, but the above examinations are not specific for PPL. PET-CT can also be used to further evaluate the characteristics of this type of disease. It should be noted that PPL has more affinity for fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) than other pancreatic tumors, and the SUVmax range from 7.4 to 26.5[14]. Although PET-CT has a certain value in the diagnosis of PPL, it can only affect the disease staging of 5% of patients. PET-CT usage in T-cell lymphomas is still debatable but provide prognostic information[20,21]. There is currently no recommendation for the staging of PPL with PET-CT. No matter what, the treatment will not change[6]. We also used FDG for further evaluation, and her SUVmax (20.3) was within this range. There was no specificity above. In some early studies, FNA was mostly used to aspirate biopsy tissue. However, EUS-FNA is widely used because of its high safety, high accuracy and high sensitivity[19]. Furthermore, this method is also minimally invasive and can be combined with laparoscopic surgery. This method has diagnostic value and can help us make a clear diagnosis of the disease faster and more accurately, but there are still some limitations. Several recent studies noted that flow cytometry and immunophenotyping should be added to EUS-FNA cytology as a complement[12,14], which is the same as this case. In a recent study, Orsini-Arman et al[22] reported four cases of PPL, confirmed as DLBCL through endosonography-guided tissue acquisition (EUS-TA), with surgical resection initially considered due to suspicion of pancreatic cancer. EUS-TA, facilitated by advanced needles, emerges as an effective tool for tissue acquisition, enhancing diagnostic accuracy and reducing adverse event rates compared to EUS-FNA in PPL[22].

WHO provides precise diagnostic criteria: The majority of the disease is localized in the pancreas; adjacent lymph node involvement and distant spread may exist, but the primary clinical presentation involves the pancreatic gland[19,23].

Although the best chemotherapy regimen remains undetermined, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone (CHOP) or a CHOP-like regimen are the first-line treatments for PTCL-NOS patients[1]. Recently, the CD30-positive cell-targeting antibody-drug combination brentuximab vedotin has been studied for the treatment of several lymphoma entities. Several studies have reported the effectiveness of vibratuximab combined with CHOP in treating T-cell lymphoma[24]. The antibody-drug conjugate brentuximab vedotin is designed to target CD30-positive cells and has been extensively studied for its effectiveness in treating various lymphoma types. According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, brentuximab vedotin in combination with CHP is recommended as a preferred first-line therapeutic option for ALCL and other CD30-positive entities, such as PTCL-NOS[17]. Furthermore, NCCN guidelines suggest brentuximab vedotin as the preferred choice for second-line therapy in patients with recurrent/refractory ALCL and other CD30-positive entities, including PTCL-NOS[1,24]. In our case, considering that the gastrointestinal reaction of an elderly patient was very severe, the tumor progressed to stage III. Flow cytometry showed abnormal T cells. Therefore, bone marrow invasion was not ruled out. We attempted a treatment regimen involving vibratuximab, obetinib, and gemcitabine in this patient, reducing the drug dose. After the first course of treatment, the patient's pancreatic mass was significantly reduced through imaging evaluation. However, these results are not as good as we expected, and the tumor size has increased. In the end, the patient unfortunately passed away due to infection caused by intestinal perforation. The current case shows the complex clinical process of treating PPL, which includes atypical symptoms, difficult diagnosis, tortuous treatment processes and poor prognosis. Be highly vigilant about possible complications.

Primary pancreatic PTCL-NOS is a malignant and heterogeneous lymphoma, in which the clinical manifestations are often nonspecific; it is difficult to diagnose, and the prognosis is poor. Imaging can only be used for auxiliary diagnosis of other diseases. With the help of immunostaining, EUS-FNA could be used to aid in the diagnosis of PPL. After a clear diagnosis, chemotherapy is still the first-line treatment for such patients, and surgical resection is not recommended. A large number of recent studies have shown that the CD30 antibody drug has potential as a therapy for several types of lymphoma. However, identifying new CD30-targeted therapies for different types of lymphoma is urgently needed. In the future, further research on antitumor therapy should be carried out to improve the survival prognosis of such patients.

| 1. | Zhang P, Zhang M. Epigenetic alterations and advancement of treatment in peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Clin Epigenetics. 2020;12:169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | O'Connor OA, Bhagat G, Ganapathi K, Pedersen MB, D'Amore F, Radeski D, Bates SE. Changing the paradigms of treatment in peripheral T-cell lymphoma: from biology to clinical practice. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:5240-5254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Foss FM, Zinzani PL, Vose JM, Gascoyne RD, Rosen ST, Tobinai K. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;117:6756-6767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Amador C, Greiner TC, Heavican TB, Smith LM, Galvis KT, Lone W, Bouska A, D'Amore F, Pedersen MB, Pileri S, Agostinelli C, Feldman AL, Rosenwald A, Ott G, Mottok A, Savage KJ, de Leval L, Gaulard P, Lim ST, Ong CK, Ondrejka SL, Song J, Campo E, Jaffe ES, Staudt LM, Rimsza LM, Vose J, Weisenburger DD, Chan WC, Iqbal J. Reproducing the molecular subclassification of peripheral T-cell lymphoma-NOS by immunohistochemistry. Blood. 2019;134:2159-2170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Foley NC, Mehta-Shah N. Management of Peripheral T-cell Lymphomas and the Role of Transplant. Curr Oncol Rep. 2022;24:1489-1499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Broccoli A, Zinzani PL. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified. Blood. 2017;129:1103-1112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Facchinelli D, Boninsegna E, Visco C, Tecchio C. Primary Pancreatic Lymphoma: Recommendations for Diagnosis and Management. J Blood Med. 2021;12:257-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lamrani FZ, Amri F, Koulali H, Mqaddem OE, Zazour A, Bennani A, Ismaili Z, Kharrasse G. Primary pancreatic lymphoma: Report of 4 cases with literature review. Radiol Case Rep. 2024;19:70-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zheng SM, Zhou DJ, Chen YH, Jiang R, Wang YX, Zhang Y, Xue HL, Wang HQ, Mou D, Zeng WZ. Pancreatic T/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:4467-4472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hughes B, Habib N, Chuang KY. Primary Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma of the Pancreas. ACG Case Rep J. 2019;6:e00231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ries RA, Jacovides CL, Rashti J, Gong JZ, Yeo CJ. Differentiating Primary Pancreatic Lymphoma Versus Primary Splenic Lymphoma: A Case Report. J Pancreat Cancer. 2021;7:20-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gan Q, Caraway NP, Ding C, Stewart JM. Primary Pancreatic Lymphoma Evaluated by Fine-Needle Aspiration. Am J Clin Pathol. 2022;158:242-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rad N, Khafaf A, Mohammad Alizadeh AH. Primary pancreatic lymphoma: what we need to know. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2017;8:749-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Anand D, Lall C, Bhosale P, Ganeshan D, Qayyum A. Current update on primary pancreatic lymphoma. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2016;41:347-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cagle BA, Holbert BL, Wolanin S, Tappouni R, Lalwani N. Knife wielding radiologist: A case report of primary pancreatic lymphoma. Eur J Radiol Open. 2018;5:141-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Battula N, Srinivasan P, Prachalias A, Rela M, Heaton N. Primary pancreatic lymphoma: diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma. Pancreas. 2006;33:192-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Horwitz SM, Ansell S, Ai WZ, Barnes J, Barta SK, Brammer J, Clemens MW, Dogan A, Foss F, Ghione P, Goodman AM, Guitart J, Halwani A, Haverkos BM, Hoppe RT, Jacobsen E, Jagadeesh D, Jones A, Kallam A, Kim YH, Kumar K, Mehta-Shah N, Olsen EA, Rajguru SA, Rozati S, Said J, Shaver A, Shea L, Shinohara MM, Sokol L, Torres-Cabala C, Wilcox R, Wu P, Zain J, Dwyer M, Sundar H. T-Cell Lymphomas, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20:285-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Johnson EA, Benson ME, Guda N, Pfau PR, Frick TJ, Gopal DV. Differentiating primary pancreatic lymphoma from adenocarcinoma using endoscopic ultrasound characteristics and flow cytometry: A case-control study. Endosc Ultrasound. 2014;3:221-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yu L, Chen Y, Xing L. Primary pancreatic lymphoma: two case reports and a literature review. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:1687-1694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Demirel BB, Efeturk H, Ucmak G, Esen Akkas B, Dogan M, Iskender D. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified-a patient with extranodal pancreatic involvement detected by FDG PET/CT: a case report and review of the literature. Nucl Med Biomed Imaging. 2018;3. |

| 21. | Choi WH, Han EJ, O JH, Choi EK, Choi JI, Park G, Choi BO, Jeon YW, Min GJ, Cho SG; Catholic University Lymphoma Group. Prognostic Value of FDG PET/CT in Patients with Nodal Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Orsini-Arman AC, Surjan RCT, Venco FE, Ardengh JC. Primary Pancreatic Lymphoma: Endosonography-Guided Tissue Acquisition Diagnosis. Cureus. 2023;15:e34936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Fléjou JF. [WHO Classification of digestive tumors: the fourth edition]. Ann Pathol. 2011;31:S27-S31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Prince HM, Hutchings M, Domingo-Domenech E, Eichenauer DA, Advani R. Anti-CD30 antibody-drug conjugate therapy in lymphoma: current knowledge, remaining controversies, and future perspectives. Ann Hematol. 2023;102:13-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Triantafillidis J, Greece; Varma V, India S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S