Published online Feb 15, 2024. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v16.i2.514

Peer-review started: November 16, 2023

First decision: December 2, 2023

Revised: December 16, 2023

Accepted: January 15, 2024

Article in press: January 15, 2024

Published online: February 15, 2024

Processing time: 78 Days and 1 Hours

Gastric cancer is the third most common cause of cancer related death worldwide. Surgery with or without chemotherapy is the most common approach with curative intent; however, the prognosis is poor as mortality rates remain high. Several indexes have been proposed in the past few years in order to estimate the survival of patients undergoing gastrectomy. The preoperative nutritional status of gastric cancer patients has recently gained attention as a factor that could affect the postoperative course and various indexes have been developed. The aim of this systematic review was to assess the role of the prognostic nutritional index (PNI) in predicting the survival of patients with gastric or gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma who underwent gastrectomy with curative intent.

To investigate the role of PNI in predicting the survival of patients with gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma.

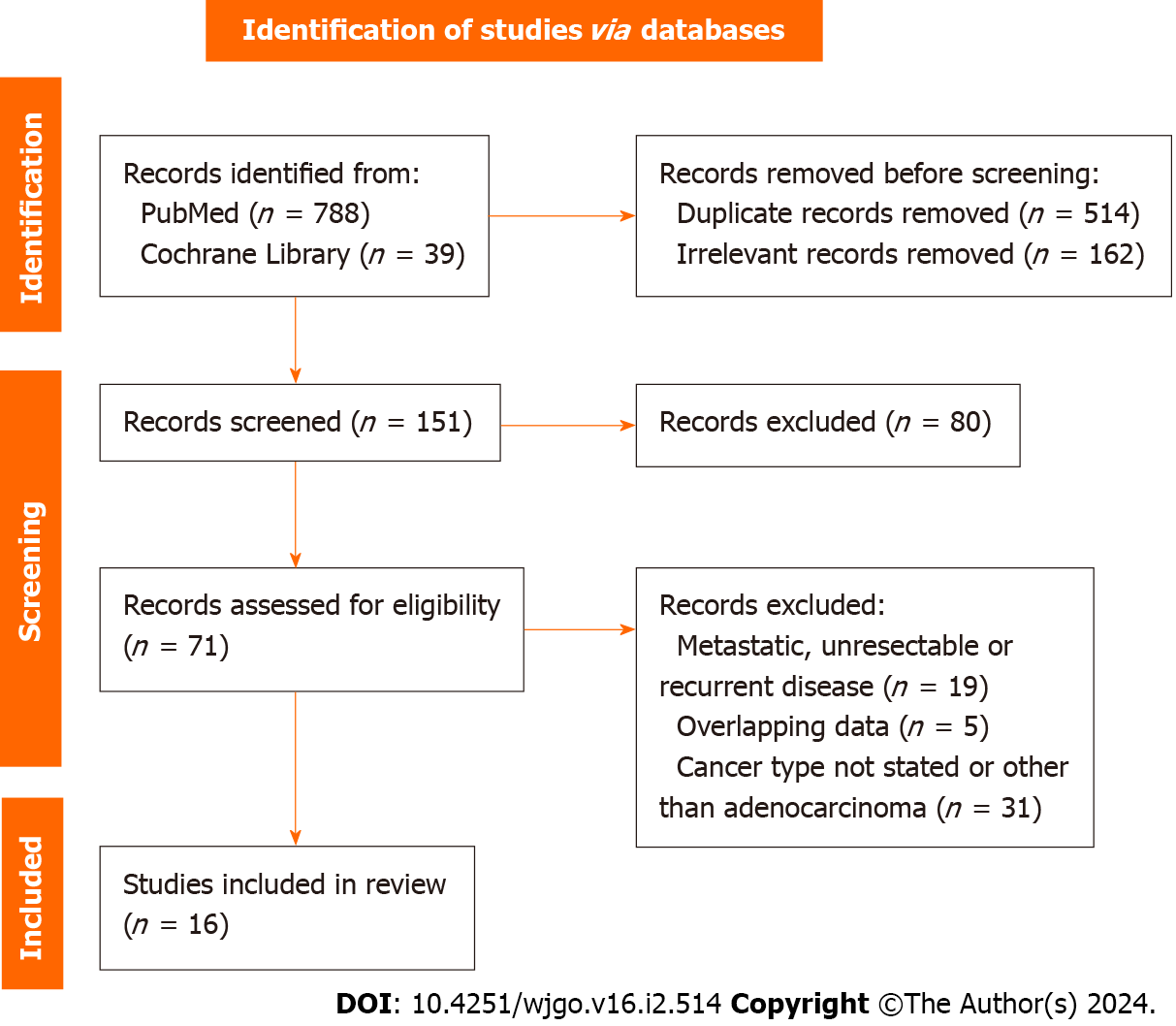

A thorough literature search of PubMed and the Cochrane library was performed for studies comparing the overall survival (OS) of patients with gastric or gastroesophageal cancer after surgical resection depending on the preoperative PNI value. The PRISMA algorithm was used in the screening process and finally 16 studies were included in this systematic review. The review protocol was regis

Sixteen studies involving 14551 patients with gastric or esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma undergoing open or laparoscopic or robotic gastrectomy with or without adjuvant chemotherapy were included in this systematic review. The patients were divided into high- and low-PNI groups according to cut-off values that were set according to previous reports or by using receiver operating characteristic curve analysis in each individual study. The 5-year OS of patients in the low-PNI groups ranged between 39% and 70.6%, while in the high-PNI groups, it ranged between 54.9% and 95.8%. In most of the included studies, patients with high preoperative PNI showed statistically significant better OS than the low PNI groups. In multivariate analyses, low PNI was repeatedly recognised as an independent prognostic factor for poor survival.

According to the present study, low preoperative PNI seems to be an indicator of poor OS of patients undergoing gastrectomy for gastric or gastroesophageal cancer.

Core Tip: In the present systematic review, we investigated the role of prognostic nutritional index (PNI) in predicting the survival of patients with gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma that were submitted to surgery with or without chemotherapy. PNI is easy to calculate and provides information about the nutritional status of the patients. Low preoperative PNI seems to be associated with worse survival in patients that will undergo surgery for gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma and therefore could be useful for decision making in clinical practice.

- Citation: Fiflis S, Christodoulidis G, Papakonstantinou M, Giakoustidis A, Koukias S, Roussos P, Kouliou MN, Koumarelas KE, Giakoustidis D. Prognostic nutritional index in predicting survival of patients with gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma: A systematic review. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2024; 16(2): 514-526

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v16/i2/514.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v16.i2.514

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most common malignancies and the third most common cause of cancer-related deaths. In 2018, there were approximately 1033701 new cases of GC reported worldwide, resulting in 783000 associated deaths[1-3]. Surgery with or without chemotherapy remains the cornerstone in the management, as it may have curative results. Despite advancements in surgical procedures, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and targeted treatments, postoperative complications and mortality rates remain high, leading to a poor prognosis for patients[4].

Pathological characteristics such as tumor stage, nodal status, and resection margin are thought to be crucial in determining cancer patient survival[5]. However, it is now obvious that tumor pathology is not the only factor that influences cancer survival; muscle mass, nutritional profile, immunological conditions, and other variables could significantly affect surgical outcomes[6,7]. Malnutrition is particularly common among this group of patients and is attributed to inadequate oral intake, protein-losing gastropathy, ongoing bleeding due to tumors, and ineffective nutri

Historically, tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification has been the most prevalent and reliable indicator for patient prognosis. However, there is an increasing number of cases where patients classified at the same stage exhibit significantly different prognoses[12,13]. Recent studies have demonstrated that perioperative inflammation-based prognostic scores can predict overall survival (OS) in patients with diverse forms of cancer[14]. Albumin levels are a key indicator of a patient’s nutritional status. Several scores based on albumin levels have been developed, such as the nutritional index (NI), Glasgow Prognostic Score, Nutrient Profiling System, and Controlling Nutritional Status score[11,15]. The prognostic NI (PNI) has gained popularity as a means of predicting the surgical risk of patients with GC. It is calculated by multiplying 10 times the serum albumin value (g/dL) plus 0.005 times the lymphocytes count (/mm3). It utilizes nutritional and inflammation status instead of tumor growth, node invasion, and metastasis stage[1,16,17]. PNI has been used as a prognostic tool for patients with solid organ tumors with significant prognostic value regarding survival and postoperative complications, paving the way for individualized perioperative management[12,17,18]. In this systematic review, we aimed to assess the role of PNI in predicting the survival of patients undergoing curative intent surgery for gastric or gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma.

A thorough literature search of PubMed and the Cochrane library was conducted for articles comparing the OS of patients with gastroesophageal cancer after surgical resection depending on their preoperative PNI over the past 10 years. The terms “prognostic nutritional index”, “PNI”, “gastric cancer”, “gastroesophageal cancer”, “gastric adenocarcinoma”, and “survival” were used in various combinations. The PubMed search yielded 788 results that were scrutinized against the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1). After title and abstract screening and exclusion of duplicates and irrelevant articles, 71 were eligible for further assessment. After full text screening, finally 16 studies were included in our systematic review. The search and screening processes were completed by two independent reviewers using the PRISMA algorithm and any conflict was resolved through discussion (Figure 1)[19]. The study protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO ID CRD42023461282).

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Cohort studies | Metastatic or recurrent disease |

| Studies in English language | Patients receiving palliative care |

| Studies published over the past 10 yr (2013 to 2023) | Cancer other than adenocarcinoma |

| Adult patients (over 18 years old) | Case-control studies |

| Patients with histologically confirmed esophagogastric or gastric adenocarcinoma | Commentaries or letters to the editor |

| Open or laparoscopic gastrectomy | |

| Effect of preoperative PNI on OS as primary outcome |

Only cohort studies were included in our systematic review. The risk of bias and the quality of each individual study were assessed using the Cochrane Tool to assess Risk of Bias in Cohort studies and the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale (NOS), respectively[20]. The Cochrane Tool consists of seven questions and according to the answers a cohort study was categorized as of low or of high risk of bias. The NOS consists of three categories (Selection, Comparability, and Outcome) and eight items. A maximum of one star can be awarded for each item within the selection and outcome categories and a maximum of two stars for the comparability[1,12,13,15,17,21-31] (Table 2). A study with a score of over six stars is considered to be of high quality.

| Ref. | Selection | Comparability | Outcomes | Total | |||||

| Representativeness of the exposed cohort | Selection of the non exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Outcome of interest not present at the start of the study | Assessment of outcome | Length of follow-up | Adequacy of follow-up | |||

| Hashimoto et al[21] | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6/8 | ||

| Hirahara et al[31] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 8/8 |

| Hirahara et al[22] | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6/8 | ||

| Ishiguro et al[23] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 7/8 | |

| Kudou et al[12] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 8/8 |

| Lee et al[13] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 8/8 |

| Lin et al[15] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 8/8 |

| Liu et al[24] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 7/8 | |

| Murakami et al[1] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 7/8 | |

| Saito et al[25] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 7/8 | |

| Shen et al[26] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 8/8 |

| Takechi et al[17] | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6/8 | ||

| Toyokawa et al[27] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 8/8 |

| Toyokawa et al[28] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 8/8 |

| Wu et al[29] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 7/8 | |

| Xu et al[30] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 8/8 |

The following data were extracted: Year of publication, institution, study period, number of participants, patient diagnosis and operation, PNI cut-off value, patient age, sex, body mass index, albumin and lymphocyte count, tumor location and TNM stage, follow-up period, OS, and the univariate and multivariate analysis results. Data extraction was completed by four of the reviewers. Any disagreement during that phase was resolved by consulting a senior reviewer.

Sixteen studies involving 14551 patients with non-metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma who underwent surgery with curative intent between 1997 and 2021 were included in our systematic review. The clinical and pathological characteristics of the patients are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

| Ref. | Institute | Period | Patients number | Sex | Age (yr) |

| Hashimoto et al[21] | Sasebo City General Hospital, Japan | 2013-2020 | 109 | 68 M, 41 F | 83 (80-94) |

| Hirahara et al[31] | Department of Digestive and General Surgery, Shimane University, Japan | 2009-2016 | 218 | 145 M, 77 F | Low PNI group (n = 109): 78 (46-91). High PNI group (n = 259): 69 (36-89) |

| Hirahara et al[22] | Department of Digestive and General Surgery, Shimane University, Japan | 2010-2016 | 368 | 254 M, 114 F | Absent postoperative complications group (n = 265): 70 (36-91). Present postoperative complications group (n = 103): 73 (41-90) |

| Ishiguro et al[23] | Department of Surgery in Yokohama City, Japan | 2015-2021 | 258 | 183 M, 75 F | 31-88 |

| Kudou et al[12] | Department of Surgery and Science, Kyushu University; Department of Gastroenterological Surgery, National Kyushu Medical Center, Japan | 2005-2016; 2010-2019 (respectively to the 2 institutes) | 206 | 151 M, 55 F | 66.3 (35-92) |

| Lee et al[13] | Severance Hospital, South Korea | 2001-2010 | 7781 | 5150 M, 2631 F | 57.1 ± 11.9 |

| Lin et al[15] | Fujian Medical University Union Hospital, China | 2009-2014 | 2182 | 1643 M, 539 F | 60.8 (54-68.3) |

| Liu et al[24] | Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, China | 2000-2012 | 1330 | 905 M, 425 F | 59 (19-89) |

| Murakami et al[1] | Tottori University Faculty of Medicine, Japan | 2001-2013 | 254 | 186 M, 68 F | > 70, n = 128; < 70, n = 126 |

| Saito et al[25] | Division of Surgical Oncology, Department of Surgery, School of Medicine, Tottori University Faculty of Medicine, Japan | 2005-2013 | 453 | 331 M, 122 F | Low PNI group (n = 188): 73.5. High PNI group (n = 265): 63.5 |

| Shen et al[26] | General Surgery Department of the Jinling Hospital, China | 2010-2018 | 525 | 387 M, 138 F | Training set (n = 369): 58.53 ± 10.14. Validation set (n = 156): 57.87 ± 10.28 |

| Takechi et al[17] | Onomichi General Hospital, Hiroshima, Japan | 2011-2014 | 182 | 130 M, 52 F | 70 (38-91) |

| Toyokawa et al[27] | Osaka City University Hospital, Japan | 1997-2012 | 240 | 168 M, 72 F | 64.5 (58-71.3) |

| Toyokawa et al[28] | Osaka City University Hospital, Japan | 1997-2012 | 225 | 147 M, 78 F | 68 (60-75) |

| Wu et al[29] | Affiliated Hospital of Jiangnan University, Jiangsu Province, China | 2015-2017 | 77 | 59 M, 18 F | 62.58 ± 8.97 |

| Xu et al[30] | Shantou University Medical College’s cancer hospital, China | 2016-2020 | 236 | 171 M, 65 F | 43.68 ± 4.62 |

The PNI cut-off values used in the studies and the survival outcomes are shown in Table 4. PNI was calculated as 10 × albumin (g/dL) + 0.005 × total lymphocyte count (/mm3) and its thresholds ranged between 44.2 and 47 in the majority of the studies; however, three studies used the cut-off values 42.3, 49.2, and 52, respectively. There were 10864 patients in the high PNI group and 3687 in the low PNI group. The patients were submitted to total or partial gastrectomy and lymphadenectomy with or without adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The primary endpoint of our study was OS and the results of univariate and multivariate analyses of the studies that were included are shown in Tables 5 and 6.

| Ref. | Tumor location | TNM stage | Operation | Chemotherapy |

| Hashimoto et al[21] | NS | I, n = 53 (48.6%). II, n = 31 (28.4%). III, n = 25 (22.9%) | Open surgery 54 (49.5%), laparoscopic 55 (50.5%). Distal/total/proximal gastrectomy: 70/37/2. D2 lymphadenectomy, n = 38 (34.9%) | Adjuvant 13 (11.9%). Neoadjuvant NS |

| Hirahara et al[31] | EGJ, n = 6. Upper, n = 41. Middle, n = 91. Lower, n = 80 | Ia-Ib, n = 92, IIa-IIb, n = 51, IIIa-IIIc, n = 75. T1/2/3/4: 80/27/45/66. N0/1/2/3: 120/30/33/35 | Laparoscopic total/laparoscopic partial/laparoscopy assisted distal gastrectomy: 60/14/144 | Adjuvant: Yes n = 79, no n = 139. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the exclusion criteria |

| Hirahara et al[22] | EGJ, n = 11. U, n = 70. M, n = 162. L, n = 125 | IA-IB, n = 217. IIA-IIB, n = 65. IIIC-IIIC, n = 86. T1/2/3/4: 192/48/54/74. N0/1/2/3: 244/40/42/42 | Laparoscopic total/laparoscopic partial/laparoscopy assisted distal gastrectomy: 82/37/249 | Adjuvant: Yes n = 100, no n = 268 |

| Ishiguro et al[23] | Upper, n = 63 (24.4%). Middle, n = 113 (43.8%). Lower, n = 82 (31.8%) | T1, n = 138 (53.5%). T2 or T3, n = 120 (46.5%). Lymphatic invasion positive/negative: 90 (34.9%)/168 (65.1%) | Total/distal/partial gastrectomy: 66/180/11. D1+/D2 lymphadenectomy: 139/112 | 77% of the patients in the high PNI group and 47% in the low PNI group (amongst stages II and III patients) |

| Kudou et al[12] | EGJ = 96, UGC = 110 | T1 97 (47.1%), T2 25 (12.1%), T3 55 (26.7%), T4 29 (14.1%). N0 136 (66.0%), N1 33 (16.0%), N2 13 (6.3%), N3 24 (11.7%). I/II/III: 113 (54.9%)/52 (25.2%)/41 (19.9%) | Total/proximal gastrectomy: 161/45. D1 lymphadenectomy (for T1 tumors), n = 97. D2 lymphadenectomy (for T2-4 tumors), n = 64 | Adjuvant: Yes, n = 51 (24.8%), no, n = 155 (75.2%). Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the exclusion criteria |

| Lee et al[13] | NS | T1 4182 (53.8%), T2 944 (12.1%), T3 913 (11.7%), T4a 1700 (21.9%), T4b 42 (0.5%). N0 4967 (63.8%), N1 941 (12.1%), N2 798 (10.3%), N3 1075 (13.8%). Stage I 4608 (59.2%), II 1286 (16.5%), III 1887 (24.3%) | Subtotal gastrectomy 5895 (75.8%). Total gastrectomy 1886 (24.2%) | Patients with stage II or higher disease were recommended for adjuvant chemotherapy (numbers not mentioned). Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the exclusion criteria |

| Lin et al[15] | Upper 521 (23.9%). Middle 465 (21.3%). Lower 923 (42.3%). Mixed 273 (12.5%) | TNM stage: I 632 (29.0), II 526 (24.1), III 1024 (46.9) | Total gastrectomy 1134 (52.0%). Distal gastrectomy 998 (45.7%). Proximal gastrectomy 50 (2.3%) | 1223 patients (56%): Adjuvant chemotherapy n = 1223 (56%). Neoadjuvant chemotherapy NS |

| Liu et al[24] | Upper third 511 (38.4%). Middle third 278 (20.9%). Lower third 541 (40.7%) | I 220 (16.5%). II 334 (25.1%). III 776 (58.3%) | D2 gastrectomy with R0 resection | Adjuvant chemotherapy n = 817. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the exclusion criteria |

| Murakami et al[1] | NS | T1 n = 147, T2/3/4 n = 107. N0 n = 181, N1/2/3 n = 73. Stage I n = 161, II/III n = 93 | Distal/proximal gastrectomy n = 181, total gastrectomy n = 73. D0/1/1+ lymphadenectomy n = 171, D2 lymphadenectomy n = 83 | NS |

| Saito et al[25] | NS | T1 n = 284, T2/3/4 n = 169. Lymph node metastasis absent/present: 343/110 | Curative gastrectomy (R0 resection) with regional dissection of lymph nodes. Partial/proximal/total gastrectomy: 311/42/100 | Adjuvant chemotherapy n = 64, neoadjuvant chemotherapy n = 5, perioperative chemotherapy n = 10 |

| Shen et al[26] | Upper 158. Middle 202. Lower 165 | Training/validation set: I 138 (37.40%)/64 (41.03%), II 84 (22.76%)/39 (25.00%), III 147 (39.84%)/53 (33.97%) | Robotic gastrectomy proximal/distal/total: 110/272/143 | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy n = 116, adjuvant n = 267 |

| Takechi et al[17] | NS | Stage: I n = 114 (62.6%), II n = 38 (20.9%), III n = 30 (16.5%) | Distal/total/proximal gastrectomy: 124 (68.1%)/51 (28%)/7 (3.8%). D1/D1+/D2 lymphadenectomy: 32 (17.6%)/74 (40.7%)/76 (41.8%) | Postoperative patients with stages II and III GC n = 33 (18.1%). Neoadjuvant NS |

| Toyokawa et al[27] | Upper n = 57 (23.8%). Middle n = 98 (40.8%). Lower n = 83 (34.6%). Whole n = 2 (0.8%) | Only stage II patients: IIA n = 111 (46.3%), IIB n = 129 (53.7%) | Total/proximal/distal gastrectomy: 72/1/167 | Adjuvant chemotherapy: Yes 62/no 178. Neoadjuvant in the exclusion criteria |

| Toyokawa et al[28] | Upper/middle/lower n = 209 (92.9%). Whole 16 (7.1%) | IIIA 80 (35.6%), IIIB 72 (32.0%), IIIC 73 (32.4%) | Total/distal gastrectomy: 108 (48%)/117 (52%) | Adjuvant chemotherapy: Yes 41 (18.2%)/no 184 (81.8%) |

| Wu et al[29] | NS | Only stage III: n = 77 (100%) | Partial gastrectomy (n = 15), total gastrectomy (n = 62) | The average number of chemotherapy cycles was 6.77 ± 4.14, and all patients completed > 2 chemotherapy cycles. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the exclusion criteria |

| Xu et al[30] | EGJ | I 48 (20.3%), II 53 (22.4%), III 135 (57.2%) | Curative gastro-esophageal resection with R0 resection | NS |

| Ref. | PNI calculation | PNI cut-off value and groups | PNI range | Follow up (months) | Outcome |

| Hashimoto et al[21] | ROC curve analysis | 44.2. PNI > 44.2 (n = 72), PNI < 44.2 (n = 37) | NS | 23.9 (0.4-81.9) | The 30-d, 180-d, 1-yr, and 3-yr cumulative OS rates were 100%, 97.0%, 91.6%, and 74.7%, respectively |

| Hirahara et al[31] | ROC curve analysis | 44.3. PNI < 44.3 (n = 109), PNI > 44.3, n = 109 | NS | Observation period from date of surgery till day of death | 5-yr OS: Low PNI, 50.9%; high PNI, 73.6% (P < 0.001). In elderly patients (age > 70) 5-yr OS: Low PNI 52.5%, high PNI 82.5%. Non elderly patients (age < 70), 5-yr OS: Low PNI 46.6%, high PNI 54.7% |

| Hirahara et al[22] | ROC curve analysis | 44.5. PNI < 44.5 n = 114, PNI > 44.5, n = 254 | NS | NS | NS |

| Ishiguro et al[23] | Set according to previous reports | 47. PNI < 47 (n = 75), PNI > 47 (n = 183) | NS | NS | 5-yr OS: A: 44.7%; B: 77.2% (P < 0.001) |

| Kudou et al[12] | ROC curve analysis | 44.7. PNI < 44.7 (n = 167, 81.1%), PNI > 44.7 (n = 39, 18.9%) | NS | 60 | Worse 5-year OS rates were associated with PNI < 44.7 (vs > 44.7) (OS: 41.7% vs 84.5%, HR = 5.460, P < 0.0001). In subgroup analysis PNI < 44.7 (vs > 44.7) was significantly associated with poor prognosis in patients with stages II and III disease |

| Lee et al[13] | ROC curve analysis | 46.7. PNI < 46,7 (n = 779), PNI > 46,7, n = 7002 | 54.2 ± 5.9 | 60 | The low PNI group had a poor prognosis for all stages of disease (for all stages and stages I, II, and III: P < 0.001) |

| Lin et al[15] | Set according to previous reports | 46. PNI ≤ 46 (n = 1348, (61.8%), PNI > 46 (n = 834, 38.2%) | NS | 52 (1-118) | Low PNI 5-yr OS = 55.5%, high PNI 5-yr OS = 75.4% |

| Liu et al[24] | Set according to previous reports | 45. Low PNI group PNI < 45. Number of patients NS | 35 (range 1-179). Final follow-up June 2015, 806 patients were alive by then | NS | |

| Murakami et al[1] | ROC curve analysis | Preoperative PNI of ≥ 52 (pre-PNIhigh) n = 82, preoperative PNI < 52 (pre-PNIlow) n = 172, postoperative PNI ≥ 49 (post-PNIhigh) n = 95, postoperative PNI < 49 (pre-PNIlow) n = 159. Group A, patients with pre-PNIhigh and post-PNIhigh; group B, patients with either pre-PNIhigh and post-PNIlow or pre-PNIlow and post-PNIhigh; group C, patients with pre-PNIlow and post-PNIlow | Preoperative PNI range 30.6-63.6. Postoperative range 24.2-61.7 | NS | 5-yr OS prePNIhigh 95.8%, prePNIlow 70% (P < 0.0001). 5-yr OS postPNIhigh 91.4%, postPNIlow 70.1% (P < 0.0001). 5-yr OS prePNIlow and postPNIhigh 80.1%, prePNIlow and postPNIlow 67.1% (P = 0.031). 5-yr OS prePNIhigh and postPNIhigh 100%, prePNIhigh and postPNIlow 83.4% (P = 0.0021) |

| Saito et al[25] | ROC curve analysis | 46.7. PNI ≥ 46.7 (n = 265, 58.5%) and PNI < 46.7 (PNIlow, n = 188, 41.5%) | Range 27.7-63.6 | NS | 5-yr OS PNIlow 59.5%, PNIhigh 88.2% (P < 0.0001) |

| Shen et al[26] | X-tile 3.6.1 software1 (Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States) | 45.39. Training set low PNI n = 48 (13.01%), high PNI 321 (86.99%), validation set low PNI n = 29 (18.59%), high PNI n = 127 (81.41%). Patients were randomly divided into the training set and the validation set at a 7:3 ratio | NS | 41 (range 2-102) training set and 38 (range 1-101) validation set | 3-yr and 5-yr OS rates were 80.9% and 74.8% in the training set, and 81.6% and 73.5% in the validation set |

| Takechi et al[17] | Set according to previous reports | 45. PNI < 45 (n = 97), PNI ≥ 45 (n = 85) | NS | 39 (range, 1-72) | NS |

| Toyokawa et al[27] | ROC curve analysis | 49.2. PNI ≤ 49.2 (n = 136), PNI > 49.2) (n = 104) | NS | 100.5 (70.0-136.8) | The 5-yr OS rate for the entire study population was 78.8% |

| Toyokawa et al[28] | ROC curve analysis | 45.6. PNI ≤ 45.6 (n = 90, 40%), PNI > 45.6 (n = 135, 60%) | 46.8 (IQR: 42.5-49.9) | Median 80 (69-124) | The 5-yr OS rate for the entire study population was 48.7%. |

| Wu et al[29] | ROC curve analysis | 42.3. Low PNI group PNI < 42.3. Number of patients NS | NS | Shortest 30, longest 64 | 3-yr OS low PNI group < 40%, high PNI group > 60%. Exact number NS (only survival curves available) |

| Xu et al[30] | ROC curve analysis | 45.6. Propensity matching patients. PNI < 45.6 (n = 58), PNI > 45.6 (n = 85) | NS | Every 3 months first 2 yr, every 12 months for 3rd-5th yr, once per year after that. Final follow-up December 2022 | Low PNI group had a 5-yr OS rate of 46.9%, high PNI group had a 5-yr OS rate of 71.30% |

| Ref. | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis |

| Hashimoto et al[21] | Low PNI associated with poor OS (P = 0.049) | Low PNI was an independent prognostic factor for poor OS (P = 0.044) |

| Hirahara et al[31] | Low PNI value was a significant risk factor for shorter OS (P < 0.001) | PNI was confirmed as an independent prognostic factor for OS (P < 0.001) |

| Hirahara et al[22] | PNI was significantly associated with OS (HR = 3.316, 95%CI: 2.133-5.196, P < 0.001) | In patients with high PNI, only CEA was was independently associated with OS (P = 0.002) |

| Ishiguro et al[23] | PNI was significantly associated with OS (P < 0.001) | PNI was an independent predictor of OS (HR = 3.452, 95%CI: 2.042-5.836, P = 0.007) |

| Kudou et al[12] | PNI < 44.7 (vs > 44.7) was associated with worse OS (P < 0.0001) | PNI (P < 0.0001, HR = 8.946) was independently associated with OS |

| Lee et al[13] | Low PNI was significantly associated with worse OS (HR = 2.864, 95%CI: 2.544-3.223, P < 0.001) | Low PNI was independently associated with OS (HR = 1.383, 95%CI: 1.221-1.568, P < 0.001) |

| Lin et al[15] | PNI was significantly associated with OS (P < 0.001) | PNI was independently associated with OS (P = 0.004) and the 5-yr OS rate in the low PNI group was significantly lower than that in the normal PNI group (55.5% vs 75.4%, P < 0.05) |

| Liu et al[24] | PNI was associated with OS (HR = 1.627, 95%CI: 1.274-2.078, P < 0.001) | PNI (HR = 1.356, 95%CI: 1.051-1.748, P = 0.019) was independently associated with OS. In stage stratified analysis PNI was not significantly associated with OS |

| Murakami et al[1] | 5-yr survival rates were 100.0, 83.0, and 67.1% for groups A, B, and C, respectively | 5-yr OS 100%, 92.4%, and 78.3% for groups A, B, and C, respectively, in non-elderly patients (age < 70) (P = 0.017). 5-yr OS 100%, 75.1%, and 59% for groups A, B, and C, respectively, for elderly patients (age > 70) (P = 0.0029). Group stratification mentioned in Table 4 |

| Saito et al[25] | NS | 5-yr OS PNI low group 59.5%, PNI high group 88.2% (P < 0.0001). Median age of the PNI high group (63.5 yr) was significantly younger than of the PNI low group (73.5 yr) |

| Shen et al[26] | PNI was an independent prognostic factor for OS. PNI (≤ 45.39 vs > 45.39) (HR = 0.439, 95%CI: 0.236-0.734, P = 0.002) | PNI was an independent prognostic factor for OS. PNI (≤ 45.39 vs > 45.39) (HR = 0.553, 95%CI: 0.306-0.993, P = 0.048) |

| Takechi et al[17] | Low PNI was significantly associated with worse OS (HR = 4.261, 95%CI: 1.734-10.47, P = 0.002). Stage I GC patients in the high PNI group showed significantly better OS than patients in the low PNI group (P < 0.001). No significant difference in OS between PNI groups in stage II and III GC patients | Only PNI score was an independent prognostic factor for OS (HR = 2.889, 95%CI: 1.104-7.563, P = 0.031) |

| Toyokawa et al[27] | PNI was significantly associated with OS (HR = 0.381, 95%CI: 0.219-0.662, P = 0.001) | PNI was an independent prognostic factor for OS (HR = 0.415, 95%CI: 0.234-0.736, P = 0.003) |

| Toyokawa et al[28] | PNI was not significantly associated with OS (P = 0.073) | PNI was not significantly associated with OS (P = 0.676) |

| Wu et al[29] | - | The group with high pre-chemotherapy PNI values had significantly better overall survival than the group with low pre-chemotherapy PNI values (HR = 0.485, 95%CI: 0.255-0.920; P = 0.027) |

| Xu et al[30] | Lower PNI was a significant predictor of shorter OS (P = 0.004) | In comparison to the high PNI group, the hazard of endpoint mortality was 2.442 times greater in the low PNI group (P = 0.003) |

PNI was significantly associated with the OS in all of the studies included except for Toyokawa et al[27] enrolled 225 patients with stage III only gastric adenocarcinoma; 184 of them were submitted to adjuvant chemotherapy and PNI was not associated with OS. Hirahara et al[22] included 368 patients that were submitted to laparoscopic or laparoscopy assisted gastrectomy and 100 of them were also submitted to adjuvant chemotherapy. The authors demonstrated in univariate analysis that PNI was significantly associated with OS; however, the same result was not reached in multivariate analysis which showed that only carcinoembryonic antigen was significantly associated with OS.

Of 258 patients who underwent curative resection for GC and were included in Ishiguro et al[23]’s study, adjuvant chemotherapy was not administered to patients with stage I GC but only to patients with stage II or III. The authors demonstrated that PNI was independently associated with OS.

Lin et al[15] included 632 patients with stage I GC, 526 with stage II, and 1024 with stage III who underwent curative gastrectomy; 56% of them received adjuvant chemotherapy. The authors showed that PNI was independently associated with OS. Saito et al[24] included 111 GC patients with and 343 without lymphatic invasion; 64 patients received adjuvant and 5 neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The authors demonstrated that high PNI was significantly associated with better OS.

Hashimoto et al[21] included only elderly patients between 80 and 94 years of age. Fifty-four of them were submitted to open surgery and fifty-five to laparoscopic surgery; however, it was not stated whether neoadjuvant chemotherapy was administered. The authors demonstrated that PNI was an independent prognostic factor for OS and reported a cumulative 3-year OS rate of 74.7%. Xu et al[30] included younger patients (mean age 43.68 ± 4.62) and they also showed that low PNI was significantly associated with lower OS.

Shen et al[26] included 525 patients with stages I-III GC in their study who were submitted to robotic gastrectomy, 116 of them to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and 267 of them to adjuvant chemotherapy, and they randomly divided the patients to a training and a validation set. The authors showed that PNI was significantly associated with OS in both sets and that PNI was an independent prognostic factor for OS.

Wu et al[29], Liu et al[24], and Toyokawa et al[27] also showed that PNI was significantly associated with OS. Of note, Wu et al[29] included only patients with stage III adenocarcinoma in their study. Toyokawa et al[28], who also included only stage III patients, demonstrated that PNI was not significantly associated with OS in those patients. In another study, which included stage II only GC patients, Toyokawa et al[27] showed that PNI was an independent prognostic factor for OS. Takechi et al[17] confirmed a significant association of PNI and OS only for stage I patients but not for stage II or III patients. Finally, Lee et al[13] and Kudou et al[12] showed that PNI was significantly associated with OS in stage-stratified analysis for stage I, stage II, and stage III gastric adenocarcinoma patients.

Murakami et al[1] reported a 5-year OS rate of 70% and 95.8% in preoperatively low- and high PNI groups, respectively (P < 0.0001). In this study, postoperative PNI values were also recorded at 1 month after surgery. The authors demonstrated that the patients with preoperative and postoperative PNI higher than the threshold had a better 5-year OS (100%) compared to those who had preoperative or postoperative PNI lower than the threshold (5-year OS 83%) and compared to the patients with preoperative and postoperative low PNI (5-year OS 67.1%). The authors also compared the 5-year OS rates of these groups in elderly (age over 70 years old) and non-elderly patients (age under 70 years old) and they reported lower OS rates for elderly patients (100% vs 75.1% vs 59% for elderly patients and 100% vs 92.4% vs 78.3% for non-elderly patients). Hirahara et al[31] also examined the 5-year OS in low- and high-PNI groups in elderly and non-elderly patients. A greater difference in 5-year OS was reported between the low- and high-PNI groups in elderly patients (52.5% vs 82.5%) compared to non-elderly patients (46.6% vs 54.7%).

In the present study, we assessed the role of PNI in the prognosis of patients with gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer. However, there are discrepancies in the literature depending on cancer stage. For instance, according to Migita et al[32], a low PNI is a significant predictor of poor OS in patients with GC at stages I and III, but not at stages II and IV. In the study of Sakurai et al[33], a low PNI was found to be a negative prognostic factor in stages I and II, but not in stage III. This disparity could be explained by the fact that, in addition to cancer stage, other clinicopathological factors, including but not limited to patient’s age, nutritional status, or lymphatic or vessel invasion, could influence the survival of patients with different stages of GC[34-36]. Of note, the data are still not conclusive as to whether PNI has better prognostic value in early or advanced GC stage[36-38].

Undoubtedly, there is a link between the nutritional status and the prognosis of patients with GC. Many studies have shown that malnutrition has a negative impact on the prognosis of cancer patients due to its effects on the immune system function resulting in impaired general health and increased treatment complications[9,36]. PNI is a systemic inflammatory marker that has been shown to be useful in cancer prognosis. However, there has been little research into the impact of inflammation on the tumor microenvironment[15]. It is unclear whether a low preoperative PNI is a cause or a result of tumor progression. A low preoperative PNI, according to a meta-analysis of Li et al[39], was significantly associated with poor OS, as well as increased postoperative mortality. Therefore, assessing nutritional status is critical because it allows for the identification of malnourished patients at high risk and the implementation of appropriate nutritional interventions that could possibly improve prognosis and reduce complications. However, Migita et al[40] showed that preoperative oral nutritional supplementation did not improve low preoperative PNI, therefore more research needs to be done regarding the optimal means of preoperative nutritional support.

The PNI cut-off values varied between the studies that were included in this systematic review and the methods that were used to calculate the PNI cut-off value are mentioned in Table 4. An optimal cut-off value for predicting long-term outcomes has not been established in the literature[36]. Future research should focus on standardizing the PNI thresholds by performing receiver operating characteristic curve analysis in prospective studies that include patients with minimum clinicopathological characteristics heterogeneity in order to identify the PNI cut-off value with the maximum sensitivity and specificity, as a standardized PNI cut-off value may have significant impact in daily clinical practice and decision-making. For instance, in the study of Kosuga et al[41], it was shown that preoperative PNI may help clarify the extent of lymphadenectomy in patients undergoing gastrectomy for GC.

In our study, there are some limitations that need to be addressed. First, all of the included studies were retrospective cohort studies, which are prone to selection or recall bias. Furthermore, not all patients included in this study had the same stage of cancer. Also, some of them received neoadjuvant therapy prior to surgery, which possibly affected the overall course of the disease. Patients were not divided according to specific tumor characteristics, such as the TNM stage, the size or depth or the tumor, the Siewert type, or the tumor differentiation, therefore a correlation between the PNI and the survival depending on the multiple tumor characteristics could not be established. It would be of interest if future studies would stratify patients and assess the prognostic significance of the PNI based on those characteristics. Due to high heterogeneity of the recorded data, a meta-analysis could not be performed. Of note, the fact that not all deaths were confirmed cancer-related deaths is something to take into account. Furthermore, the studies that we included in our study were all performed in Eastern Asia countries and there were no studies performed in Western countries that matched our inclusion criteria. This could be attributed to the fact that East Asia has the highest prevalence of GC (20-25 patients per 100000, less than 5 patients per 100000 in Northern America)[42]. Finally, patients underwent operations in different institutions by different surgical teams of variable experience, which may have had an impact on the postoperative events.

In conclusion, all of the studies that we included showed that patients with higher preoperative PNI demonstrate better survival than those with lower PNI after surgery for gastric or gastroesophageal cancer with or without chemotherapy regardless of the tumor stage, patients age, total or partial gastrectomy, and open or laparoscopic gastrectomy, except for one study that included stage III GC patients. Future studies should focus on stratifying patients based on tumor stage, as well as on standardizing the PNI cut-offs. Moreover, more research needs to be done in terms of preoperative nutritional support as it could increase PNI and therefore improve short- and long-term outcomes. Moreover, more studies should be performed in Western countries in order to examine whether the association between PNI and survival persists in those patients who undoubtedly present different genetic factors. Finally, PNI could be a useful clinical tool, as it is easy to calculate with standard everyday labs and may lead to individualized patient care and clinical decisions with optimal results.

Gastric cancer (GC) is a major health problem worldwide. Patients with GC that are eligible for surgery are submitted to gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy followed or not by adjuvant chemotherapy. It is important to identify prognostic factors that could predict the survival of those patients. The prognostic nutritional index (PNI) is an indicator of the nutritional and immune status of GC patients that could assist in identifying patients that will benefit the most from being submitted to surgery and that will present better survival rates.

GC patients with high preoperative PNI seem to present higher survival rates than those with lower PNI. PNI is easy to calculate and low-cost but in order to be used in everyday clinical practice, future research should be conducted to establish a standardized PNI threshold for GC patients that could be submitted to surgery.

To identify whether the PNI could be used in predicting survival outcomes in patients with GC that are submitted to surgery.

We performed a thorough literature search of PubMed, the Cochrane library, and Reference Citation Analysis for cohort studies that included patients with gastric adenocarcinoma who were submitted to gastrectomy. The keywords that we used for our search were “Prognostic nutritional index”, “survival”, and “gastric cancer” in combinations, which lead to the retrieval of 16 studies that matched our inclusion criteria. We performed risk of bias assessment and quality assessment of each individual study and our study was prospectively registered in PROSPERO.

Our systematic review showed that the PNI could be an important prognostic marker in patients undergoing surgery for gastric adenocarcinoma. All of the studies that we included demonstrated that preoperative PNI is significantly associated with survival in GC patients except for one study which included stage III only gastric adenocarcinoma patients. However, two of the studies that we included showed that PNI is significantly associated with survival in patients with stage III gastric adenocarcinoma. Further studies should aim to identify a standardized PNI threshold for gastric adenocarcinoma patients. Moreover, future studies should analyze the correlation between PNI and the stage of disease and whether PNI is associated with survival regardless of the disease stage.

PNI could be an important prognostic marker that could assist in predicting the survival of patients submitted to gastrectomy.

Future research should aim at identifying a standardized PNI cut-off value. Furthermore, the correlation between PNI and tumor stage, Lauren classification, and patients’ clinicopathological characteristics should be analyzed.

| 1. | Murakami Y, Saito H, Kono Y, Shishido Y, Kuroda H, Matsunaga T, Fukumoto Y, Osaki T, Ashida K, Fujiwara Y. Combined analysis of the preoperative and postoperative prognostic nutritional index offers a precise predictor of the prognosis of patients with gastric cancer. Surg Today. 2018;48:395-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Park SH, Lee S, Song JH, Choi S, Cho M, Kwon IG, Son T, Kim HI, Cheong JH, Hyung WJ, Choi SH, Noh SH, Choi YY. Prognostic significance of body mass index and prognostic nutritional index in stage II/III gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020;46:620-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18694] [Cited by in RCA: 21466] [Article Influence: 1951.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 4. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 56690] [Article Influence: 7086.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (135)] |

| 5. | Liu YP, Ma L, Wang SJ, Chen YN, Wu GX, Han M, Wang XL. Prognostic value of lymph node metastases and lymph node ratio in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:155-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 6. | Schwegler I, von Holzen A, Gutzwiller JP, Schlumpf R, Mühlebach S, Stanga Z. Nutritional risk is a clinical predictor of postoperative mortality and morbidity in surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2010;97:92-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Takahashi T, Saikawa Y, Kitagawa Y. Gastric cancer: current status of diagnosis and treatment. Cancers (Basel). 2013;5:48-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sasahara M, Kanda M, Ito S, Mochizuki Y, Teramoto H, Ishigure K, Murai T, Asada T, Ishiyama A, Matsushita H, Tanaka C, Kobayashi D, Fujiwara M, Murotani K, Kodera Y. The Preoperative Prognostic Nutritional Index Predicts Short-Term and Long-Term Outcomes of Patients with Stage II/III Gastric Cancer: Analysis of a Multi-Institution Dataset. Dig Surg. 2020;37:135-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lien YC, Hsieh CC, Wu YC, Hsu HS, Hsu WH, Wang LS, Huang MH, Huang BS. Preoperative serum albumin level is a prognostic indicator for adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:1041-1048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhao Y, Deng Y, Peng J, Sui Q, Lin J, Qiu M, Pan Z. Does the Preoperative Prognostic Nutritional Index Predict Survival in Patients with Liver Metastases from Colorectal Cancer Who Underwent Curative Resection? J Cancer. 2018;9:2167-2174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kubota T, Shoda K, Konishi H, Okamoto K, Otsuji E. Nutrition update in gastric cancer surgery. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2020;4:360-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kudou K, Nakashima Y, Haruta Y, Nambara S, Tsuda Y, Kusumoto E, Ando K, Kimura Y, Hashimoto K, Yoshinaga K, Saeki H, Oki E, Sakaguchi Y, Kusumoto T, Ikejiri K, Shimokawa M, Mori M. Comparison of Inflammation-Based Prognostic Scores Associated with the Prognostic Impact of Adenocarcinoma of Esophagogastric Junction and Upper Gastric Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28:2059-2067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lee JY, Kim HI, Kim YN, Hong JH, Alshomimi S, An JY, Cheong JH, Hyung WJ, Noh SH, Kim CB. Clinical Significance of the Prognostic Nutritional Index for Predicting Short- and Long-Term Surgical Outcomes After Gastrectomy: A Retrospective Analysis of 7781 Gastric Cancer Patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e3539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hirahara N, Matsubara T, Mizota Y, Ishibashi S, Tajima Y. Prognostic value of preoperative inflammatory response biomarkers in patients with esophageal cancer who undergo a curative thoracoscopic esophagectomy. BMC Surg. 2016;16:66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lin JX, Lin LZ, Tang YH, Wang JB, Lu J, Chen QY, Cao LL, Lin M, Tu RH, Huang CM, Li P, Zheng CH, Xie JW. Which Nutritional Scoring System Is More Suitable for Evaluating the Short- or Long-Term Prognosis of Patients with Gastric Cancer Who Underwent Radical Gastrectomy? J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24:1969-1977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hirahara N, Tajima Y, Fujii Y, Kaji S, Yamamoto T, Hyakudomi R, Taniura T, Kawabata Y. Prognostic nutritional index as a predictor of survival in resectable gastric cancer patients with normal preoperative serum carcinoembryonic antigen levels: a propensity score matching analysis. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Takechi H, Fujikuni N, Tanabe K, Hattori M, Amano H, Noriyuki T, Nakahara M. Using the preoperative prognostic nutritional index as a predictive factor for non-cancer-related death in post-curative resection gastric cancer patients: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20:256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Migita K, Matsumoto S, Wakatsuki K, Ito M, Kunishige T, Nakade H, Kitano M, Nakatani M, Kanehiro H. A decrease in the prognostic nutritional index is associated with a worse long-term outcome in gastric cancer patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Surg Today. 2017;47:1018-1026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 51894] [Article Influence: 10378.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 20. | Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Losos WM, Tugwell P, Wells Ga S, Zello G, Petersen J. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta- analysis. [cited 14 December 2023]. Available from: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. |

| 21. | Hashimoto S, Araki M, Sumida Y, Wakata K, Hamada K, Kugiyama T, Shibuya A, Nishimuta M, Nakamura A. Short- and Long-term Outcome After Gastric Cancer Resection in Patients Aged 80 Years and Older. Cancer Diagn Progn. 2022;2:201-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hirahara N, Tajima Y, Fujii Y, Kaji S, Kawabata Y, Hyakudomi R, Yamamoto T. High Preoperative Prognostic Nutritional Index Is Associated with Less Postoperative Complication-Related Impairment of Long-Term Survival After Laparoscopic Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24:2852-2855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ishiguro T, Aoyama T, Ju M, Kazama K, Fukuda M, Kanai H, Sawazaki S, Tamagawa H, Tamagawa A, Cho H, Hara K, Numata M, Hashimoto I, Maezawa Y, Segami K, Oshima T, Saito A, Yukawa N, Rino Y. Prognostic Nutritional Index as a Predictor of Prognosis in Postoperative Patients With Gastric Cancer. In Vivo. 2023;37:1290-1296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Liu X, Qiu H, Kong P, Zhou Z, Sun X. Gastric cancer, nutritional status, and outcome. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:2107-2114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Saito H, Kono Y, Murakami Y, Kuroda H, Matsunaga T, Fukumoto Y, Osaki T. Influence of prognostic nutritional index and tumor markers on survival in gastric cancer surgery patients. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2017;402:501-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Shen D, Zhou G, Zhao J, Wang G, Jiang Z, Liu J, Wang H, Deng Z, Ma C, Li J. A novel nomogram based on the prognostic nutritional index for predicting postoperative outcomes in patients with stage I-III gastric cancer undergoing robotic radical gastrectomy. Front Surg. 2022;9:928659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Toyokawa T, Muguruma K, Tamura T, Sakurai K, Amano R, Kubo N, Tanaka H, Yashiro M, Hirakawa K, Ohira M. Comparison of the prognostic impact and combination of preoperative inflammation-based and/or nutritional markers in patients with stage II gastric cancer. Oncotarget. 2018;9:29351-29364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Toyokawa T, Muguruma K, Yoshii M, Tamura T, Sakurai K, Kubo N, Tanaka H, Lee S, Yashiro M, Ohira M. Clinical significance of prognostic inflammation-based and/or nutritional markers in patients with stage III gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wu P, Du R, Yu Y, Tao F, Ge X. Nutritional statuses before and after chemotherapy predict the prognosis of Chinese patients after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2020;29:706-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Xu S, Zhu H, Zheng Z. Preoperative Prognostic Nutritional Index Predict Survival in Patients with Resectable Adenocarcinoma of the Gastroesophageal Junction: A Retrospective Study Based on Propensity Score Matching Analyses. Cancer Manag Res. 2023;15:591-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Hirahara N, Tajima Y, Fujii Y, Yamamoto T, Hyakudomi R, Taniura T, Kaji S, Kawabata Y. Preoperative Prognostic Nutritional Index Predicts Long-term Outcome in Gastric Cancer: A Propensity Score-matched Analysis. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:4735-4746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Migita K, Takayama T, Saeki K, Matsumoto S, Wakatsuki K, Enomoto K, Tanaka T, Ito M, Kurumatani N, Nakajima Y. The prognostic nutritional index predicts long-term outcomes of gastric cancer patients independent of tumor stage. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2647-2654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Sakurai K, Ohira M, Tamura T, Toyokawa T, Amano R, Kubo N, Tanaka H, Muguruma K, Yashiro M, Maeda K, Hirakawa K. Predictive Potential of Preoperative Nutritional Status in Long-Term Outcome Projections for Patients with Gastric Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:525-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Urabe M, Yamashita H, Watanabe T, Seto Y. Comparison of Prognostic Abilities Among Preoperative Laboratory Data Indices in Patients with Resectable Gastric and Esophagogastric Junction Adenocarcinoma. World J Surg. 2018;42:185-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Sun K, Chen S, Xu J, Li G, He Y. The prognostic significance of the prognostic nutritional index in cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140:1537-1549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 319] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Yang Y, Gao P, Song Y, Sun J, Chen X, Zhao J, Ma B, Wang Z. The prognostic nutritional index is a predictive indicator of prognosis and postoperative complications in gastric cancer: A meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:1176-1182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Jiang N, Deng JY, Ding XW, Ke B, Liu N, Zhang RP, Liang H. Prognostic nutritional index predicts postoperative complications and long-term outcomes of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10537-10544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 38. | Sun KY, Xu JB, Chen SL, Yuan YJ, Wu H, Peng JJ, Chen CQ, Guo P, Hao YT, He YL. Novel immunological and nutritional-based prognostic index for gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:5961-5971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Li J, Xu R, Hu DM, Zhang Y, Gong TP, Wu XL. Prognostic Nutritional Index Predicts Outcomes of Patients after Gastrectomy for Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Nonrandomized Studies. Nutr Cancer. 2019;71:557-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Migita K, Matsumoto S, Wakatsuki K, Kunishige T, Nakade H, Miyao S, Sho M. Effect of Oral Nutritional Supplementation on the Prognostic Nutritional Index in Gastric Cancer Patients. Nutr Cancer. 2021;73:2420-2427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Kosuga T, Konishi T, Kubota T, Shoda K, Konishi H, Shiozaki A, Okamoto K, Fujiwara H, Kudou M, Arita T, Morimura R, Murayama Y, Kuriu Y, Ikoma H, Nakanishi M, Otsuji E. Value of Prognostic Nutritional Index as a Predictor of Lymph Node Metastasis in Gastric Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2019;39:6843-6849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Shin WS, Xie F, Chen B, Yu P, Yu J, To KF, Kang W. Updated Epidemiology of Gastric Cancer in Asia: Decreased Incidence but Still a Big Challenge. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: Greece

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Liu T, China; Sun Y, China; Wan XH, China S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Yu HG