Published online Jun 15, 2020. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v12.i6.632

Peer-review started: January 11, 2020

First decision: April 7, 2020

Revised: May 13, 2020

Accepted: May 14, 2020

Article in press: May 14, 2020

Published online: June 15, 2020

Processing time: 155 Days and 10.3 Hours

For laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery, the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) can be ligated at its origin from the aorta [high ligation (HL)] or distally to the origin of the left colic artery [low ligation (LL)]. Whether different ligation levels are related to different postoperative complications, operation time, and lymph node yield remains controversial. Therefore, we designed this study to determine the effects of different ligation levels in rectal cancer surgery.

To investigate the operative results following HL and LL of the IMA in rectal cancer patients.

From January 2017 to July 2019, this retrospective cohort study collected information from 462 consecutive rectal cancer patients. According to the ligation level, 235 patients were assigned to the HL group while 227 patients were assigned to the LL group. Data regarding the clinical characteristics, surgical characteristics and complications, pathological outcomes and postoperative recovery were obtained and compared between the two groups. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the possible risk factors for anastomotic leakage (AL).

Compared to the HL group, the LL group had a significantly lower AL rate, with 6 (2.8%) cases in the LL group and 24 (11.0%) cases in the HL group (P = 0.001). The HL group also had a higher diverting stoma rate (16.5% vs 7.5%, P = 0.003). A multivariate logistic regression analysis was subsequently performed to adjust for the confounding factors and confirmed that HL (OR = 3.599; 95%CI: 1.374-9.425; P = 0.009), tumor located below the peritoneal reflection (OR = 2.751; 95%CI: 0.772-3.985; P = 0.031) and age (≥ 65 years) (OR = 2.494; 95%CI: 1.080-5.760; P = 0.032) were risk factors for AL. There were no differences in terms of patient demographics, pathological outcomes, lymph nodes harvested, blood loss, hospital stay and urinary function (P > 0.05).

In rectal cancer surgery, LL should be the preferred method, as it has a lower AL and diverting stoma rate.

Core tip: Anastomotic leakage (AL) is one of the most common and serious postoperative complications of colorectal surgery and is a major cause of postoperative mortality and morbidity. Our study shows that low ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery in rectal cancer patients has a lower AL rate and diverting stoma rate. Older age and tumor located below the peritoneal reflection are also risk factors for AL. In rectal cancer surgery, low ligation should be the preferred method.

- Citation: Chen JN, Liu Z, Wang ZJ, Zhao FQ, Wei FZ, Mei SW, Shen HY, Li J, Pei W, Wang Z, Yu J, Liu Q. Low ligation has a lower anastomotic leakage rate after rectal cancer surgery. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2020; 12(6): 632-641

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v12/i6/632.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v12.i6.632

With the improvement in living standards and changes in dietary habits, the incidence and mortality of rectal cancer in China is increasing. It is one of the most common causes of cancer-related deaths in both Western and Asian countries[1]. In the 1980s, Heald proposed the total mesorectal excision (TME) concept, which resulted in revolutionary changes in surgical technology for rectal cancer[2]. In recent years, laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery has rapidly replaced open surgery, which has obvious advantages in short-term outcomes, such as less pain, less blood loss, and faster recovery. Two techniques are used to handle the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) and its branches during surgery: High ligation (HL) and low ligation (LL). The debate regarding HL and LL dates back more than 100 years. In 1908, Miles and Moynihan performed LL and HL, respectively. Moynihan believed that HL could achieve a better total number of lymph nodes harvested[3]. Nowadays, some scholars believe that LL can reduce the incidence of postoperative complications, especially the anastomotic leakage (AL) rate; however, other studies suggest that HL can obtain a higher lymph node yield, and shorten the operation time, without having any effect on the AL[4-6]. A recent nationwide cohort study in Sweden showed that the ligation level did not influence patients’ overall survival and oncological outcomes[7].

AL is one of the most common and serious complications after laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery. A large number of studies have shown that the lower the anastomosis, the higher the AL rate[8,9]. Recent studies have reported that the AL rate after rectal cancer surgery is 3% to 26%[10-12]. The occurrence of AL prolongs hospitalization time, increases the economic and mental burden for patients and increases short-term morbidity and mortality[13,14]. Poor blood supply is an important factor in AL. After HL, the blood supply to the anastomosis is mainly from the marginal artery formed by the middle colic artery, while LL of the IMA can preserve the left colic artery and its branches, which can theoretically provide more blood perfusion for the distal colon, therefore reducing the incidence of AL[3,15]. However, some studies have suggested that different approaches to IMA ligation do not change the AL rate[4,15,16]. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to investigate whether different ligation levels affect the perioperative outcomes.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the National Cancer Center and it conformed to the ethical standards of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. All patients signed an informed consent. A total of 462 consecutive rectal cancer patients who underwent TME at the National Cancer Center/National Sciences Research Center for Cancer/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College from July 2017 to July 2019 were enrolled in this study. The mean age of the patients was 58.4 ± 9.0 years; 244 (52.8%) patients were men and 218 (47.2%) patients were women. The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) Patients with rectal adenocarcinoma confirmed by endoscopic biopsy; (2) Patients confirmed to have TNM stage I-III by magnetic resonance imaging/computed tomography at the time of diagnosis; (3) The distal margin of the tumor was located within 15 cm from the anal verge; and (4) Patients who had undergone laparoscopic rectal surgery using the double stapling end-to-end technique. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Stage IV at diagnosis; (2) Patients who underwent intersphincteric resection or abdominal perineal resection; (3) Patients who underwent emergency surgery; and (4) Patients whose medical records were not complete.

The enrolled patients were assigned to the following two groups: The HL group (n = 235), patients who underwent ligation at the root of the IMA; and the LL group (n = 227), patients who under ligation just below the origin of the left colic artery (LCA) branch. All operations were performed by experienced surgeons who majored in colorectal cancer.

All patients underwent bowel preparation with oral sulfate-free polyethylene glycol electrolyte powder the day before surgery. Antibiotics were instilled once 30 min before surgery and once within 24 h after surgery.

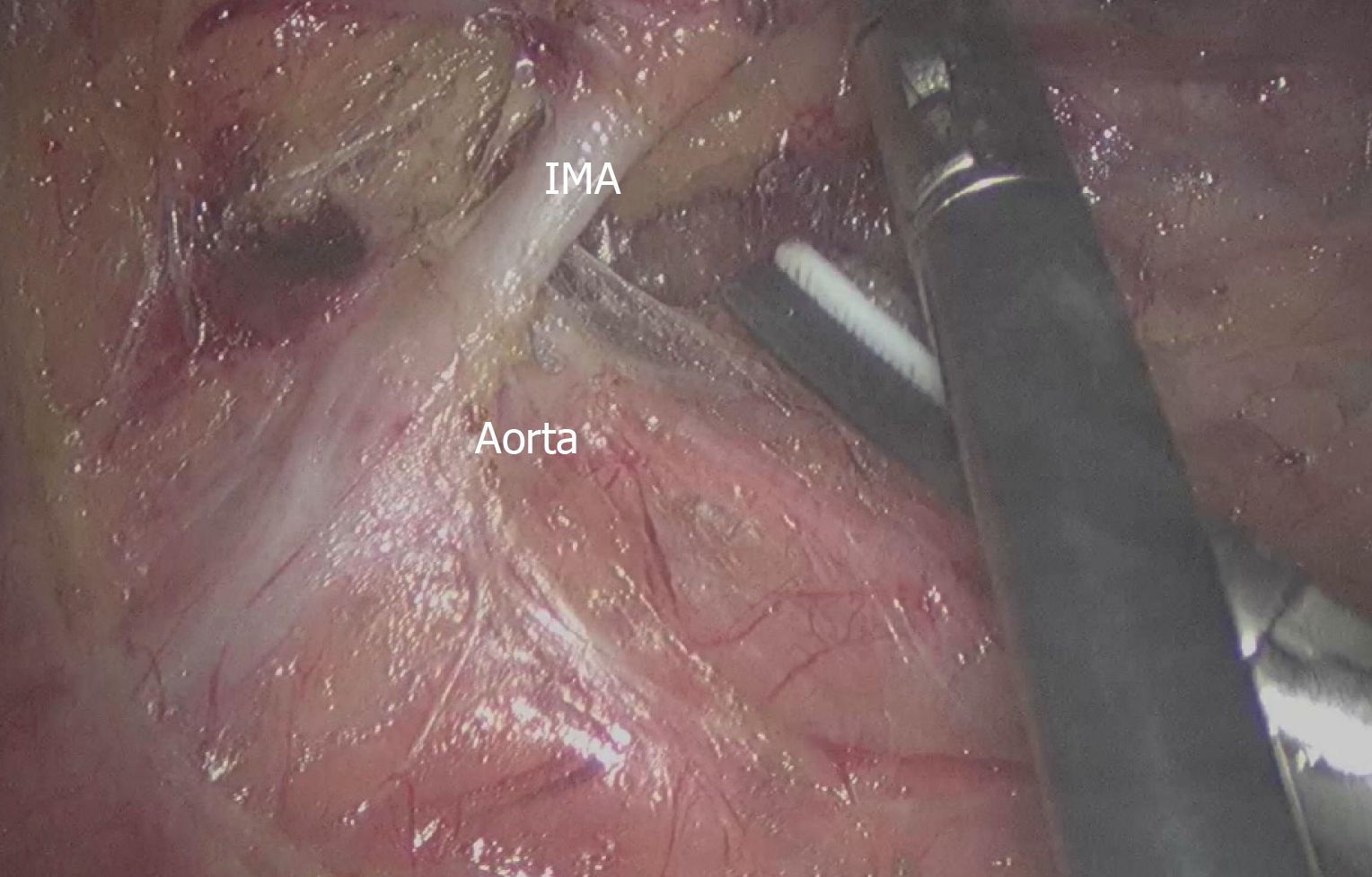

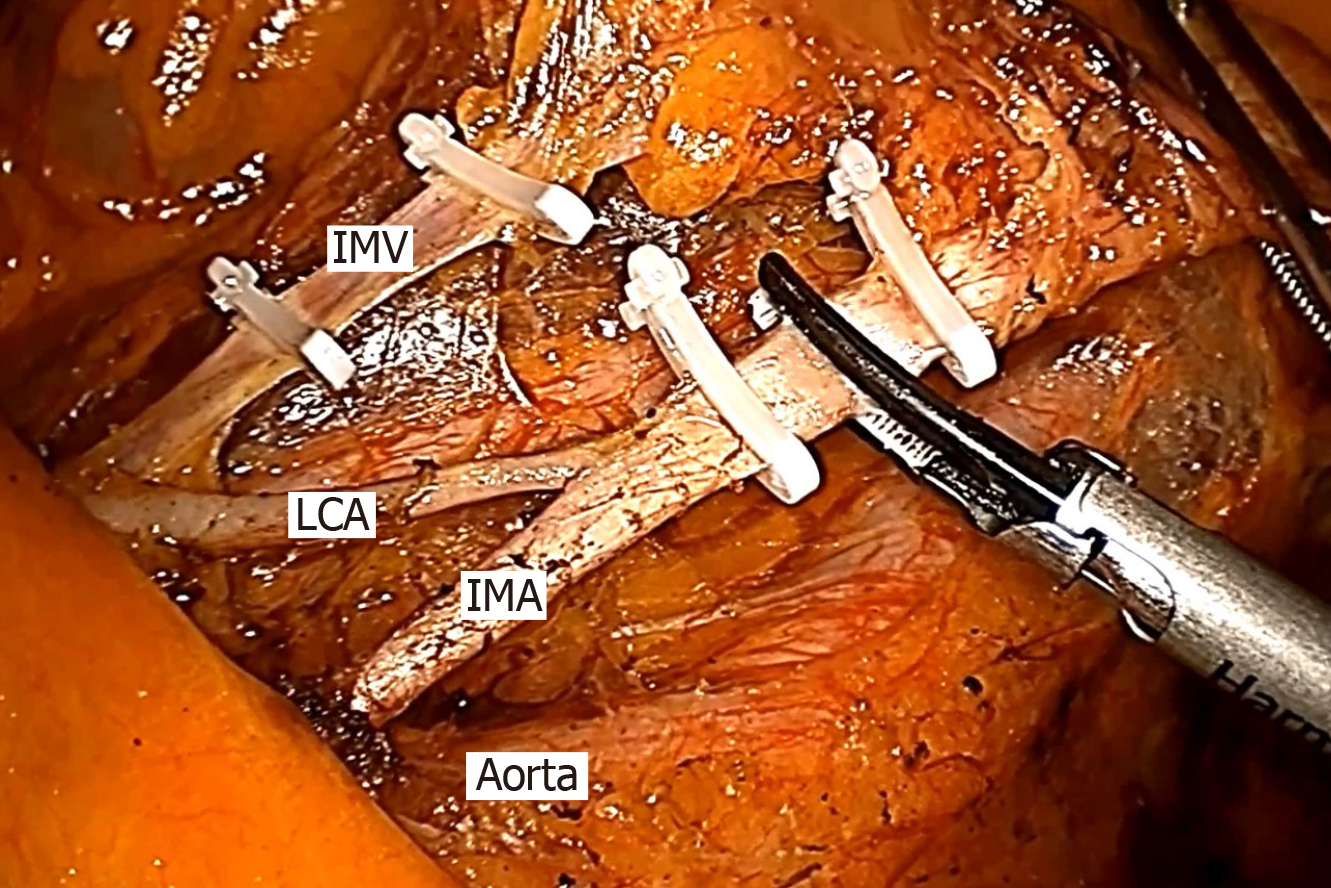

The patients were placed in the modified lithotomy position after anesthesia and all underwent laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery with TME. We performed laparoscopic resection for rectal cancer patients using four trocars (2 mm × 12 mm and 2 mm × 0.5 mm), and a pneumoperitoneum was created at 12 mmHg. The camera trocar was inserted in the umbilical region or the adjacent area. The pelvic peritoneum was opened, and the hypogastric nerves were identified and preserved. A double stapling technique was used to form an end-to-end anastomotic stoma. According to the distal colonic blood supply and the tension of the anastomotic stoma, surgeons decided whether to perform anterior resection (AR), Hartmann’s procedure or loop-ileostomy. According to the preferences of different surgeons, whether to retain the LCA was decided during the operation. In the HL group, the IMA was divided and ligated at 1 cm from its origin to avoid damaging the nerves (n = 235), and the fatty tissue around the root of the IMA was swept to harvest the maximum number of metastatic lymph nodes (Figure 1). In the LL group (n = 227), the sheath of the IMA was carefully exposed all the way to the LCA and the adipose tissue with lymph nodes of the triangular area of the aorta, IMA and the LCA was dissected (Figure 2). Two pelvic drainage tubes were placed along the anastomotic stoma for both groups. A transanal tube was also placed in some patients, to reduce the postoperative AL rate by decreasing intraluminal pressure and preventing fecal extrusion through the staple line. The tumor stage was decided by professional pathologists according to the 7th and 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer.

The urinary catheter was removed on the morning of the 5th postoperative day. Before removal, the clamping test was performed. If the patients were unable to void urine within 8 h after catheter removal and the bladder was distended on physical examination, residual urine volume was measured by ultrasound. Postoperative urinary retention was defined when residual urine volume was ≥ 150 mL, and reinsertion of an indwelling urinary catheter was required.

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 21.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) was used for data analyses. We excluded patients whose information was not clearly recorded in their medical records, and there were no missing data in this study. Quantitative data are shown as the mean ± SD and were analyzed by the t-test. Categorical data are shown as frequencies and percentages and were analyzed by the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. To decrease any confounding bias and to evaluate the comparability between the HL and LL group, a total of 23 variables were included in our investigation. All factors can be roughly divided into patient demographics, surgical data and complications, and pathological outcomes. All these data were collected from detailed medical records. Multivariate logistic regression analysis and stratification analysis were performed in the AR + anastomosis patients to examine the predictors of AL in calculating the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Differences were considered significant when the P value was less than 0.05. The data were reviewed by a biomedical statistician in our institution.

Between July 2017 and July 2019, 462 patients with rectal cancer treated at the National Cancer Center/Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences were included in this study. The baseline characteristics of the HL group (n = 235, 50.9%) and LL group (n = 227, 49.1%) are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of gender, age, body mass index, American Society of Anesthesiologists score or history of neoadjuvant chemoradiation.

| Variables | High ligation (n = 235) | Low ligation (n = 227) | P value |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.356 | ||

| Male | 127 (54.0) | 117 (51.5) | |

| Female | 108 (46.0) | 110 (48.5) | |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 57.9 ± 9.1 | 58.6 ± 8.9 | 0.57 |

| BMI (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 24.1 ± 2.6 | 23.7 ± 3.1 | 0.761 |

| Neoadjuvant therapy, n (%) | 80 (34.0) | 75 (33.0) | 0.819 |

| ASA score, n (%) | 0.624 | ||

| ASA I | 80 (34.0) | 69 (30.4) | |

| ASA II | 127 (54.0) | 126 (55.5) | |

| ASA III | 28 (12.0) | 32 (14.1) |

The surgical data and related postoperative complications are summarized in Table 2. The transanal tube placement rate was significantly higher in the HL group (62.5% vs 42.3%, P < 0.001). In addition, a significantly higher incidence of AL was observed in the HL group than in the control group (10.2% vs 2.6%, P = 0.001). With regard to the type of operation performed, conversion to open surgery, estimated blood loss and number of harvested lymph nodes, there were no significant differences. The operation time in the LL group was longer than that in the HL group, but was not statistically significant (163.1 ± 51.3 min vs 174.4 ± 49.8 min, P = 0.142). Also, postoperative complications including anastomotic bleeding and urinary dysfunction were not significantly different between the two groups. All complications were successfully resolved. In terms of recovery, there were no significant differences in time to first flatus and hospital stay after surgery (2.1 ± 0.6 d vs 1.9 ± 0.8 d, P = 0.177; 7.0 ± 1.2 d vs 6.3 ± 1.3 d, P = 0.236, respectively). There were no deaths reported within 30 days after surgery in either group.

| Variables | High ligation (n = 235) | Low ligation (n = 227) | P value |

| Type of operation, n (%) | 0.453 | ||

| AR + anastomosis | 218 (92.7) | 216 (95.1) | |

| AR + Hartmann's procedure | 5 (2.1) | 2 (0.9) | |

| AR + anastomosis + ileostomy | 12 (5.1%) | 9 (4.0) | |

| Conversion to open surgery, n (%) | 4 (1.7%) | 6 (2.6) | |

| Operation time (min, mean ± SD) | 163.1 ± 51.3 | 174.4 ± 61.8 | 0.142 |

| Estimated blood loss (mL, mean ± SD) | 47.5 ± 21.2 | 52.6 ± 23.7 | 0.363 |

| Number of harvested lymph nodes (mean ± SD) | 16.8 ± 6.2 | 13.7 ± 7.4 | 0.399 |

| Transanal tube, n (%) | 147 (62.5) | 96 (42.3) | < 0.001 |

| Anastomotic leakage, n (%) | 24 (10.2) | 6 (2.6) | 0.001 |

| Anastomotic bleeding, n (%) | 4 (1.7) | 3 (1.3) | 0.738 |

| Urinary dysfunction, n (%) | 9 (3.8) | 7 (3.1) | 0.661 |

| Time to first flatus (d, mean ± SD) | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 0.177 |

| Hospital stay after operation (d, mean ± SD) | 7.0 ± 1.2 | 6.3 ± 1.3 | 0.236 |

Table 3 shows the pathological results and no significant differences between the two groups were observed.

| Variables | High ligation (n = 235) | Low ligation (n = 227) | P value |

| Tumor size (cm, mean ± SD) | 4 ± 0.7 | 4.1 ± 0.8 | 0.314 |

| Tumor location, n (%) | 0.114 | ||

| Below the peritoneal reflection | 127 (54.0) | 106 (46.7) | |

| Above the peritoneal reflection | 108 (46.0) | 121 (53.3) | |

| Differentiation degree, n (%) | 0.324 | ||

| Poor | 66 (28.1) | 50 (22.0) | |

| Moderate | 146 (62.1) | 153 (67.4) | |

| Well | 23 (9.8) | 24 (10.6) | |

| p-Stage, n (%) | 0.184 | ||

| I | 24 (10.2) | 19 (8.4) | |

| II | 95 (40.4) | 111 (48.9) | |

| III | 116 (49.4) | 97 (42.7) |

Stratification analysis was performed to control for confounding biases. Details of AL in the AR + anastomosis group are shown in Table 4. Depending on the impact of AL on clinical management, three grades of leakage severity were defined and classified as grade A (subclinical leak, no therapy changes), grade B (non-surgical therapy change), and grade C (surgery required), and according to the International Study Group of Rectal Cancer criteria[17] clinical AL occurred in a total of 30 (7.1%) patients. Two patients were readmitted to hospital due to delayed AL. Two of thirty patients had grade B leakage, they received conservative treatment and were discharged within three weeks. The remaining twenty-eight patients suffered grade C AL and received a loop ileostomy. Our data showed a significant difference in the AL rate between the HL and LL groups who underwent AR + anastomosis (11.0% vs 2.8%, P = 0.001). Several previous studies have suggested that the risk factors for AL included age, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, preservation of LCA, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, gender, transanal tube placement, tumor location, and tumor stage[18,19]. We carried out a multivariate logistic regression analysis to analyze factors that might influence AL (Table 5). After adjusting for confounding factors, the regression model demonstrated that HL (OR = 3.599; 95%CI: 1.374-9.425; P = 0.009), age (≥ 65 years) (OR = 2.494; 95%CI: 1.080-5.760; P = 0.032) and tumor located below the peritoneal reflection (OR = 2.751; 95%CI: 0.772-3.985; P = 0.031) were associated with an increased risk of AL.

| Variables | High ligation (n = 218) | Low ligation (n = 216) | P value |

| AL patients, n (%) | 24 (11.0) | 6 (2.8) | 0.001 |

| Grade, n (%) | 0.464 | ||

| A | 0 | 0 | |

| B | 2 (0.1) | 0 | |

| C | 22 (10.1) | 6 (2.8) | |

| Onset of AL, n (%) | 0.464 | ||

| Early AL | 22 (10.1) | 6 (2.8) | |

| Delayed AL | 2 (0.1) | 0 |

| Variables | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| High or Low ligation | 0.009 | 3.599 | 1.374-9.425 |

| Age (< 65 yr or ≥ 65 yr) | 0.032 | 2.494 | 1.080-5.760 |

| ASA score | 0.108 | 1.798 | 0.879-3.675 |

| Neoadjuvant therapy | 0.058 | 2.144 | 0.974-4.717 |

| Gender | 0.195 | 0.583 | 0.258-1.317 |

| Transanal tube | 0.180 | 1.754 | 0.772-3.985 |

| Tumor location | 0.031 | 2.715 | 1.098-5.760 |

| pTNM | 0.477 | 1.245 | 0.680-2.280 |

Table 6 shows the overall diverting stoma rate (12.1%). Thirty-nine (16.5%) patients in the HL group and seventeen (7.5%) in the LL group had a diverting stoma, and the difference between the groups was statistically significant (P = 0.003).

| Variables | High ligation (n = 235) | Low ligation (n = 227) | P value |

| Stoma, n (%) | 0.003 | ||

| Yes | 39 (16.5) | 17 (7.5) | |

| No | 196 (83.5) | 210 (92.5) |

The controversy regarding the ligation level of the IMA in rectal cancer has continued for over 100 years since 1908 when Miles recommended a division of the IMA distal to the branching of the LCA, while Moynihan suggested resection of the IMA at its origin. The main arguments are mainly related to two aspects: Oncologic and anatomic.

The focus of the debate on the oncological result is whether LL can result in a complete lymphadenectomy especially at the root of the IMA, obtain accurate pTNM staging to guide follow-up treatment, and consequently improve the prognosis of patients with metastatic lymph nodes. The results of a study in Japan which enrolled 1188 patients showed that HL improved the 5-year overall survival rate up to 40% in patients with IMA root lymph node metastasis[20]. Moreover, according to a study conducted by researchers in Taiwan, the apical lymph node metastatic rate was low, at 0% (pT1), 1.0% (pT2), 2.6% (pT3), and 4.3% (pT4), respectively, and apical lymph node dissection was more beneficial in pT4 patients[21]. Several other studies have also shown that the incidence of metastatic apical lymph nodes ranges from 0.3% to 8.6%[22-25]. Boström et al[7] recently published a nationwide cohort study and showed that the level of ligation did not influence the oncological outcome or overall survival. Sakamoto et al[26] investigated the potential impact of the lymph-vascular microanatomy of the IMA, and their findings partially support the surgical concept of LCA preserving lymph node dissection around the IMA due to potential metastasis in the lymphatic ducts within the IMA sheath. However, our experience indicated that HL is not the only way to eradicate apical lymph nodes and the IMA sheath. In our study, we dissected the IMA sheath and the adipose tissue with lymph nodes in the triangular area of the aorta, IMA and the LCA in the LL group (Figure 2). As our results show, the number of harvested lymph nodes was not significantly different between the HL group and the LL group (16.8 ± 6.2 vs 15.9 ± 7.4, P = 0.399). Therefore, there is no contradiction between LCA preservation and apical lymph node dissection. Laparoscopic dissection of the lymph nodes with preservation of LCA is technically demanding, and the operation time was longer in the LL group, but was not significantly different (163.1 ± 51.3 min vs 174.4 ± 61.8 min, P = 0.142).

With regard to the anatomical aspect, the effect of different ligation levels on AL was considered. AL is one of the most common and serious complications, and the reported incidence of AL after AR varies from 3%-26%[10,12,27]. AL results in a postoperative mortality rate of 6%-9%[28]. The most two important factors in preventing AL is to ensure the anastomosis is tension-free and has a sufficient blood supply. Following HL, the anastomosis blood supply is from the middle colic artery and marginal arteries. Riolan’s arch, which is derived from the superior mesenteric artery, is believed to be the marginal arteries that provide perfusion of the transverse and descending colon after HL[29]. Griffiths reported that the middle colic artery is absent in 22% of patients. In such cases, the right colic artery joins the marginal artery near the hepatic flexure, and the LCA is large and its terminal branches extend into the transverse colon, and under these circumstances, Rioland’s arch may not supply enough blood to the distal colon and hence ischemia may occur after HL of the IMA. This view has been confirmed by several other authors[30]. Seike et al[31] used laser Doppler to assess the blood flow caused by the ligation level and reported a reduction of 38.5% ± 1.8% in blood flow in HL patients. Several other studies also reported that compared to HL, the perfusion of the proximal loop of the anastomosis was better after LL[32]. If ischemia is found during surgery, more bowel will need to be dissected, and the AR may change to Hartmann’s procedure. It is possible that after surgery, the patient may have another diverting operation due to AL. However, Rutegård et al[33] reported that colonic perfusion was not markedly affected by HL of the IMA. In our clinical experience, after LL, the color of the proximal colon is better, and the bleeding of the end is better than that after HL. In addition, as there is no need to resect more colon, the tension of the anastomosis was better in the LL group. A multicenter study also suggested that preservation of the LCA during laparoscopic AR for middle and low rectal cancers is associated with lower AL rates (7.4% vs 13.2%, P = 0.005)[34]. Several others studies have reported the same conclusion[35-37]. Our study also suggested a statistically higher rate of AL and diverting stoma in the HL group (10.2% vs 2.6%, P = 0.001; 16.5% vs 7.5%, P = 0.003, respectively).

The multivariate logistic regression analysis in our study also indicated that older age (≥ 65) and tumor located below the peritoneal reflection are common risk factors for AL (OR = 2.494; 95%CI: 1.080-5.760; P = 0.032 and OR = 2.751; 95%CI: 0.772-3.985; P = 0.031, respectively). Older patients are more likely to have diabetes, atherosclerotic stenosis, and decreased tissue healing ability; therefore, the probability of AL is higher[12,38,39]. Another possible cause of AL is tumor location. For tumors located below the peritoneal reflection, anastomosis will be more difficult. This will cause more tissue trauma, more tension, and a poorer blood supply. Some studies have even suggested that the level of anastomosis was the most important predictive factor for leakage[18,40].

The main limitation of our study lies in its retrospective nature, and we mainly focused on short-term postoperative complications and there is the risk of selection bias, information bias and confounding bias, although we tried to obtain as many variables as possible and incorporated them into the multivariate analysis and stratification analysis. A larger, multicenter randomized controlled trial is needed to confirm the superiority of LL over HL in rectal cancer surgery.

In conclusion, our study results showed a lower AL and diverting stoma rate in the LL group. In rectal cancer surgery, LL should be the preferred method.

Rectal cancer is a common malignancy of the digestive tract, and laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery has rapidly replaced open surgery. The ligation level of the inferior mesenteric artery during the surgery remains a controversial topic.

There is a lack of consensus concerning the management of the left colic artery in the low anterior resection of rectal cancer. Whether ligation level is associated with anastomotic leakage (AL) is still under debate. There are limited data regarding surgical outcomes of total mesorectal excision with left colic artery preservation.

The main aim of this study was to investigate whether different ligation levels affect perioperative outcomes.

We performed a retrospective cohort study and enrolled rectal cancer patients treated with different ligation levels. Information regarding the clinicopathological features and clinical outcomes were obtained and analyzed. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the possible risk factors for AL in rectal cancer patients.

Preservation of the left colic artery was associated with a significantly lower AL rate. Tumor located below the peritoneal reflection and age (≥ 65 years) were also risk factors for AL.

Our study showed a lower AL and diverting stoma rate in the left colic artery preservation group. Low ligation should be the preferred method for rectal cancer patients.

Larger prospective multicenter clinal studies need to be performed so that standard management regarding the left colic artery in rectal cancer can be established.

The authors are grateful to Gretchen Gao for producing the figures and tables.

| 1. | Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:115-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11444] [Cited by in RCA: 13321] [Article Influence: 1332.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Heald RJ, Ryall RD. Recurrence and survival after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Lancet. 1986;1:1479-1482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1867] [Cited by in RCA: 1933] [Article Influence: 48.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Miles WE. A method of performing abdomino-perineal excision for carcinoma of the rectum and of the terminal portion of the pelvic colon (1908). CA Cancer J Clin. 1971;21:361-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cirocchi R, Trastulli S, Farinella E, Desiderio J, Vettoretto N, Parisi A, Boselli C, Noya G. High tie versus low tie of the inferior mesenteric artery in colorectal cancer: a RCT is needed. Surg Oncol. 2012;21:e111-e123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Guo Y, Wang D, He L, Zhang Y, Zhao S, Zhang L, Sun X, Suo J. Marginal artery stump pressure in left colic artery-preserving rectal cancer surgery: a clinical trial. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:576-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Matsuda K, Hotta T, Takifuji K, Yokoyama S, Oku Y, Watanabe T, Mitani Y, Ieda J, Mizumoto Y, Yamaue H. Randomized clinical trial of defaecatory function after anterior resection for rectal cancer with high versus low ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery. Br J Surg. 2015;102:501-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Boström P, Hultberg DK, Häggström J, Haapamäki MM, Matthiessen P, Rutegård J, Rutegård M. Oncological Impact of High Vascular Tie After Surgery for Rectal Cancer: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Ann Surg. 2019;. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Frasson M, Granero-Castro P, Ramos Rodríguez JL, Flor-Lorente B, Braithwaite M, Martí Martínez E, Álvarez Pérez JA, Codina Cazador A, Espí A, Garcia-Granero E; ANACO Study Group. Risk factors for anastomotic leak and postoperative morbidity and mortality after elective right colectomy for cancer: results from a prospective, multicentric study of 1102 patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31:105-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Detry RJ, Kartheuser A, Delriviere L, Saba J, Kestens PJ. Use of the circular stapler in 1000 consecutive colorectal anastomoses: experience of one surgical team. Surgery. 1995;117:140-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Peeters KC, Tollenaar RA, Marijnen CA, Klein Kranenbarg E, Steup WH, Wiggers T, Rutten HJ, van de Velde CJ; Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group. Risk factors for anastomotic failure after total mesorectal excision of rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2005;92:211-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 492] [Cited by in RCA: 513] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 11. | Jestin P, Påhlman L, Gunnarsson U. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after rectal cancer surgery: a case-control study. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:715-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee WS, Yun SH, Roh YN, Yun HR, Lee WY, Cho YB, Chun HK. Risk factors and clinical outcome for anastomotic leakage after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. World J Surg. 2008;32:1124-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang ZJ, Tao JH, Chen JN, Mei SW, Shen HY, Zhao FQ, Liu Q. Intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy increases the incidence of anastomotic leakage after anterior resection of rectal tumors. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;11:538-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Boström P, Haapamäki MM, Rutegård J, Matthiessen P, Rutegård M. Population-based cohort study of the impact on postoperative mortality of anastomotic leakage after anterior resection for rectal cancer. BJS Open. 2019;3:106-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yang Y, Wang G, He J, Zhang J, Xi J, Wang F. High tie versus low tie of the inferior mesenteric artery in colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2018;52:20-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rutegård M, Hemmingsson O, Matthiessen P, Rutegård J. High tie in anterior resection for rectal cancer confers no increased risk of anastomotic leakage. Br J Surg. 2012;99:127-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rahbari NN, Weitz J, Hohenberger W, Heald RJ, Moran B, Ulrich A, Holm T, Wong WD, Tiret E, Moriya Y, Laurberg S, den Dulk M, van de Velde C, Büchler MW. Definition and grading of anastomotic leakage following anterior resection of the rectum: a proposal by the International Study Group of Rectal Cancer. Surgery. 2010;147:339-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 732] [Cited by in RCA: 1100] [Article Influence: 68.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 18. | Kawada K, Sakai Y. Preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative risk factors for anastomotic leakage after laparoscopic low anterior resection with double stapling technique anastomosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:5718-5727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhang W, Lou Z, Liu Q, Meng R, Gong H, Hao L, Liu P, Sun G, Ma J, Zhang W. Multicenter analysis of risk factors for anastomotic leakage after middle and low rectal cancer resection without diverting stoma: a retrospective study of 319 consecutive patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32:1431-1437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kanemitsu Y, Hirai T, Komori K, Kato T. Survival benefit of high ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery in sigmoid colon or rectal cancer surgery. Br J Surg. 2006;93:609-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chin CC, Yeh CY, Tang R, Changchien CR, Huang WS, Wang JY. The oncologic benefit of high ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery in the surgical treatment of rectal or sigmoid colon cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:783-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Dworak O. Morphology of lymph nodes in the resected rectum of patients with rectal carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. 1991;187:1020-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kawamura YJ, Sakuragi M, Togashi K, Okada M, Nagai H, Konishi F. Distribution of lymph node metastasis in T1 sigmoid colon carcinoma: should we ligate the inferior mesenteric artery? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:858-861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Steup WH, Moriya Y, van de Velde CJ. Patterns of lymphatic spread in rectal cancer. A topographical analysis on lymph node metastases. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:911-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Uehara K, Yamamoto S, Fujita S, Akasu T, Moriya Y. Impact of upward lymph node dissection on survival rates in advanced lower rectal carcinoma. Dig Surg. 2007;24:375-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sakamoto W, Yamada L, Suzuki O, Kikuchi T, Okayama H, Endo H, Fujita S, Saito M, Momma T, Saze Z, Ohki S, Kono K. Microanatomy of inferior mesenteric artery sheath in colorectal cancer surgery. J Anus Rectum Colon. 2019;3:167-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Law WI, Chu KW, Ho JW, Chan CW. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after low anterior resection with total mesorectal excision. Am J Surg. 2000;179:92-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | den Dulk M, Marijnen CA, Collette L, Putter H, Påhlman L, Folkesson J, Bosset JF, Rödel C, Bujko K, van de Velde CJ. Multicentre analysis of oncological and survival outcomes following anastomotic leakage after rectal cancer surgery. Br J Surg. 2009;96:1066-1075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lange JF, Komen N, Akkerman G, Nout E, Horstmanshoff H, Schlesinger F, Bonjer J, Kleinrensink GJ. Riolan's arch: confusing, misnomer, and obsolete. A literature survey of the connection(s) between the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries. Am J Surg. 2007;193:742-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Meyers MA. Griffiths' point: critical anastomosis at the splenic flexure. Significance in ischemia of the colon. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1976;126:77-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Seike K, Koda K, Saito N, Oda K, Kosugi C, Shimizu K, Miyazaki M. Laser Doppler assessment of the influence of division at the root of the inferior mesenteric artery on anastomotic blood flow in rectosigmoid cancer surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:689-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Komen N, Slieker J, de Kort P, de Wilt JH, van der Harst E, Coene PP, Gosselink MP, Tetteroo G, de Graaf E, van Beek T, den Toom R, van Bockel W, Verhoef C, Lange JF. High tie versus low tie in rectal surgery: comparison of anastomotic perfusion. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:1075-1078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Rutegård M, Hassmén N, Hemmingsson O, Haapamäki MM, Matthiessen P, Rutegård J. Anterior Resection for Rectal Cancer and Visceral Blood Flow: An Explorative Study. Scand J Surg. 2016;105:78-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Hinoi T, Okajima M, Shimomura M, Egi H, Ohdan H, Konishi F, Sugihara K, Watanabe M. Effect of left colonic artery preservation on anastomotic leakage in laparoscopic anterior resection for middle and low rectal cancer. World J Surg. 2013;37:2935-2943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Boström P, Haapamäki MM, Matthiessen P, Ljung R, Rutegård J, Rutegård M. High arterial ligation and risk of anastomotic leakage in anterior resection for rectal cancer in patients with increased cardiovascular risk. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:1018-1027. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Sörelius K, Svensson J, Matthiessen P, Rutegård J, Rutegård M. A nationwide study on the incidence of mesenteric ischaemia after surgery for rectal cancer demonstrates an association with high arterial ligation. Colorectal Dis. 2019;21:925-931. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Kato H, Munakata S, Sakamoto K, Sugimoto K, Yamamoto R, Ueda S, Tokuda S, Sakuraba S, Kushida T, Orita H, Sakurada M, Maekawa H, Sato K. Impact of Left Colonic Artery Preservation on Anastomotic Leakage in Laparoscopic Sigmoid Resection and Anterior Resection for Sigmoid and Rectosigmoid Colon Cancer. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2018;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Jung SH, Yu CS, Choi PW, Kim DD, Park IJ, Kim HC, Kim JC. Risk factors and oncologic impact of anastomotic leakage after rectal cancer surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:902-908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Parthasarathy M, Greensmith M, Bowers D, Groot-Wassink T. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after colorectal resection: a retrospective analysis of 17 518 patients. Colorectal Dis. 2017;19:288-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Sciuto A, Merola G, De Palma GD, Sodo M, Pirozzi F, Bracale UM, Bracale U. Predictive factors for anastomotic leakage after laparoscopic colorectal surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:2247-2260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 263] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 30.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Brisinda G, Exbrayat JM S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Webster JR E-Editor: Xing YX