Published online May 15, 2020. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v12.i5.592

Peer-review started: December 30, 2019

First decision: February 21, 2020

Revised: March 23, 2020

Accepted: April 18, 2020

Article in press: April 18, 2020

Published online: May 15, 2020

Processing time: 135 Days and 13.3 Hours

Rectal cancer (RC) is one of the most common diagnosed cancers, and one of the major causes of cancer-related death nowadays. Majority of the current guidelines rely on TNM classification regarding therapy regiments, however recent studies suggest that additional histopathological findings could affect the disease course.

To determine whether perineural invasion alone or in combination with lymphovascular invasion have an effect on 5-years overall survival (OS) of RC patients.

A prospective study included newly diagnosed stage I-III RC patients treated and followed at the Digestive Surgery Clinic, Clinical Center of Serbia, between the years of 2014–2016. All patients had their diagnosis histologically confirmed in accordance with both TMN and Dukes classification. In addition, the patient’s demographics, surgical details, postoperative pathological details, differentiation degree and their correlation with OS was investigated.

Of 245 included patients with stage I-III RC, lymphovascular invasion (LVI) was identified in 92 patients (38%), whereas perineural invasion (PNI) was present in 46 patients (19%). Using Kaplan-Meier analysis for overall survival rate, we have found that both LVI and PNI were associated with lower survival rates (P < 0.01). Moreover when Cox multiple regression model was used, LVI, PNI, older age, male gender were predictors of poor prognosis (HR = 5.49; 95%CI: 2.889-10.429; P < 0.05).

LVI and PNI were significant factors predicting worse prognosis in early and intermediate RC patients, hence more aggressive therapy should be reserved for these patients after curative resection.

Core tip: Perineural invasion alone is a strong predictor of poor survival of rectal cancer patients, however combined with lymphovascular invasion suggest even worse prognosis in these patients, even in early stages, hence adjuvant therapy should be administered in these cases.

- Citation: Stojkovic Lalosevic M, Milovanovic T, Micev M, Stojkovic M, Dragasevic S, Stulic M, Rankovic I, Dugalic V, Krivokapic Z, Pavlovic Markovic A. Perineural invasion as a prognostic factor in patients with stage I-III rectal cancer – 5-year follow up. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2020; 12(5): 592-600

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v12/i5/592.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v12.i5.592

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is still the most common gastrointestinal malignancy Worldwide, and one of the most common cancers in general population[1]. Concerning geographical distribution, among different regions in Europe, South-eastern Europe has one of the highest incidences and mortality rates of CRC[2]. Recent data of the Institute of Public Health of Serbia, have marked CRC as the second most common malignancy in men, with an incidence of approximately 70 per 100000 individuals[3]. Rectal cancer (RC) accounts about one third of all diagnosed CRCs, with rising incidence especially in in Western countries[4]. Earlier studies have speculated that left-sided CRC and right-sided CRC are potentially two biologically distinct entities, with different molecular pathways as well as different clinical and histopathological characteristics. It has been noted that patients with RC are older, with larger tumor diameter as well as higher metastasis rate, poorer differentiation and high reoccurrence rate[5]. Features affecting the outcome of these patients are multiple, and different histology markers have been proposed as important prognostic factors. Despite the fact that previous studies have examined numerous markers regarding the adequate staging of the disease, TNM staging is still used in everyday clinical practice, although it relays only on the anatomic progression of the disease. Though TNM staging has proven as applicable in very early and very late disease stages, still its accuracy in the intermediary stages of the disease remains controversial[6]. Precise pathological examination is needed in order to determine which patients would benefit from adjuvant therapy. Earlier investigations have observed that the presence of perineural invasion (PNI) or/as well as lymphovascular invasion (LVI) considerably correlates with the cancer-related outcome[7]. PNI is defined as invasion of nervous structures by malignant cells, whereas LVI is considered as presence of malignant cells in blood/lymphatic vessels. Considering adjuvant therapy is reserved for RC patients with locally advanced stage III, it remains challenging whether patients with earlier stages should receive adjuvant therapy. In the present study we aimed to analyze the clinical significance of PNI as well as LVI in patients with stage I-III RC and to investigate whether these two histopathological features alone or combined affect overall survival of RC patients.

A prospective study included newly diagnosed stage I-III RC patients treated and followed at the Clinic for Digestive Surgery, Clinical Center of Serbia, between the years of 2014–2016. All recruited patients had their diagnosis histologically confirmed in accordance with both TNM and Dukes classification[8]. Patients obtained diagnosis of RC adenocarcinoma initially on histopathology reports after colonoscopy and later confirmed after surgical treatment. All patients underwent abdominal ultrasonography, abdominal and pelvic CT/or MRI, or endorectal ultrasonography when necessary and chest radiography. In addition, the patient’s demographics, surgical details, histopathological details and postoperative outcome were also noted. Histopathology details included: Size of the tumor as well as infiltration, number of involved lymph nodes, differentiation, LVI, PNI and all other characteristics of standard protocol were recorded. Lymphovascular invasion has been defined as presence of cancer cells in vascular or lymphatic structures, whereas perineural invasion has been defined as presence of cancer cells in any of the layers of nerve sheath or perineural space[7]. PNI and LVI were detected using routine H&E staining. Patients with locally advanced stage RC received adjuvant chemoradiotherapy, consisted of 44-50 Gy radiotherapy delivered into the whole pelvis, and capecitabine or 5-FU as chemotherapy. Surgical treatment was according to principles of total or partial mesorectal excision[9]. Patients meeting the following criteria were excluded from our study: (1) Recurrent RC or metastatic RC disease; (2) Prior 5-years history of other malignancy; (3) Presence of inflammatory bowel disease; (4) Histopathologically confirmed squamocellular carcinoma or neuroendocrine tumor; and (5) Unresectable RC. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical board (approval number 56-6, Clinical center of Serbia) and was performed in accordance with principles of Helsinki declaration. Informed written consent was obtained from all recruited subjects.

Statistical analysis was carried out using the SPSS ver. 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Patient’s demographics, clinical and pathological characteristics were summarized. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD. Normality of distribution was investigated by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The clinicopathological variables between the groups were analyzed using χ2 test. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date the diagnosis has been made till the date of lethal outcome or the date of last follow-up. Disease free survival (DFS) was calculated from the date the diagnosis has been made till the date of last follow-up. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis has been used for plot of survival data and differences were analyzed by log-rank test. Cox proportional hazard models were used to analyze survival by each variable. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Demographic, clinical and pathological characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1. The mean follow-up time in our cohort of patients was 45 mo.

| Variable | RC |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 62.27 ± 10.74 |

| Gender (male/female), n (%) | 150 (61)/90 (29) |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 25.27 ± 3.55 |

| T stage, n (%) | |

| 1 | 42 (17) |

| 2 | 56 (23) |

| 3 | 117 (48) |

| 4 | 30 (12) |

| N stage, n (%) | |

| 0 | 146 (60) |

| 1 | 61 (25) |

| 2 | 38 (15) |

| TNM stage AJCC, n (%) | |

| I | 87 (36) |

| II | 59 (24) |

| III | 99 (40) |

| Patological differentiation, n (%) | |

| Well | 188 (76) |

| Moderate | 50 (21) |

| Poor | 7 (3) |

| Lymphovascular invasion, n (%) | |

| Absent | 153 (62) |

| Present | 92 (38) |

| Perineural invasion, n (%) | |

| Absent | 199 (81) |

| Present | 46 (19) |

| Residual status, n (%) | |

| R0 | 212 (87) |

| R1 | 33 (13) |

| Adjuvant therapy, n (%) | |

| Yes | 104 (42) |

| No | 141 (58) |

| Smoking, n (%) | |

| Ever | 173 (70) |

| Never | 72 (30) |

| Average size of tumor (mm) | 152 ± 292 |

We found no significant differences regarding age, sex and body mass index in different PNI as well as LVI status (P > 0.05). However, there was statistically significant difference in T stage, N stage and differentiation grade in patients with different PNI status (P < 0.05) (Table 2). Moreover, we found statistically significant difference in same tumor characteristics regarding LVI status (P < 0.05). Additionally, patients with LVI and PNI had more advanced disease in the setting of T stage as well as N stage, and a tendency towards poorer differentiation (P < 0.05).

| Characteristics | PNI absent | PNI present | P value | LVI absent | LVI present | P value |

| Age | 62.39 ± 10.58 | 61.72 ± 11.58 | 0.730 | 61.89 ± 10.52 | 62.89 ± 11.14 | 0.491 |

| Gender (male/female) | 123/76 | 27/19 | 0.409 | 97/56 | 53/39 | 0.222 |

| BMI | 25.46 ± 3.58 | 24.40 ± 3.33 | 0.067 | 25.66 ± 3.66 | 25.61 ± 3.27 | 0.270 |

| CEA | 11.58 ± 38.33 | 31.37 ± 148.37 | 0.379 | 9.85 ± 39.11 | 24.44 ± 108.03 | 0.223 |

| CA 19-9 | 16.86 ± 23.88 | 48.24 ± 158.40 | 0.192 | 15.64 ± 22.25 | 34.74 ± 114.60 | 0.123 |

| T stage, n (%) | ||||||

| T1 | 42 (100) | 0 (0) | 0.000 | 41 (98) | 1 (2) | 0.000 |

| T2 | 54 (96) | 2 (4) | 44 (79) | 12 (21) | ||

| T3 | 90 (77) | 27 (23) | 59 (50) | 58 (50) | ||

| T4 | 13 (43) | 17 (57) | 9 (30) | 21 (70) | ||

| N stage, n (%) | ||||||

| 0 | 137 (94) | 9 (6) | 0.000 | 123 (84) | 23 (16) | 0.000 |

| 1 | 39 (64) | 22 (36) | 24 (39) | 37 (61) | ||

| 2 | 23 (60) | 15 (40) | 6 (16) | 32 (84) | ||

| TNM, n (%) | ||||||

| Stage I | 86 (99) | 1 (1) | 0.000 | 81 (93) | 6 (7) | 0.000 |

| Stage II | 51 (86) | 8 (14) | 42 (71) | 17 (29) | ||

| Stage III | 62 (63) | 37 (37) | 30 (30) | 69 (70) | ||

| Differentiation grade, n (%) | ||||||

| Well | 157 (83) | 31 (17) | 0.023 | 125 (66) | 63 (34) | 0.018 |

| Moderate | 39 (78) | 11 (22) | 25 (50) | 25 (50) | ||

| Poor | 3 (43) | 4 (57) | 3 (43) | 4 (57) |

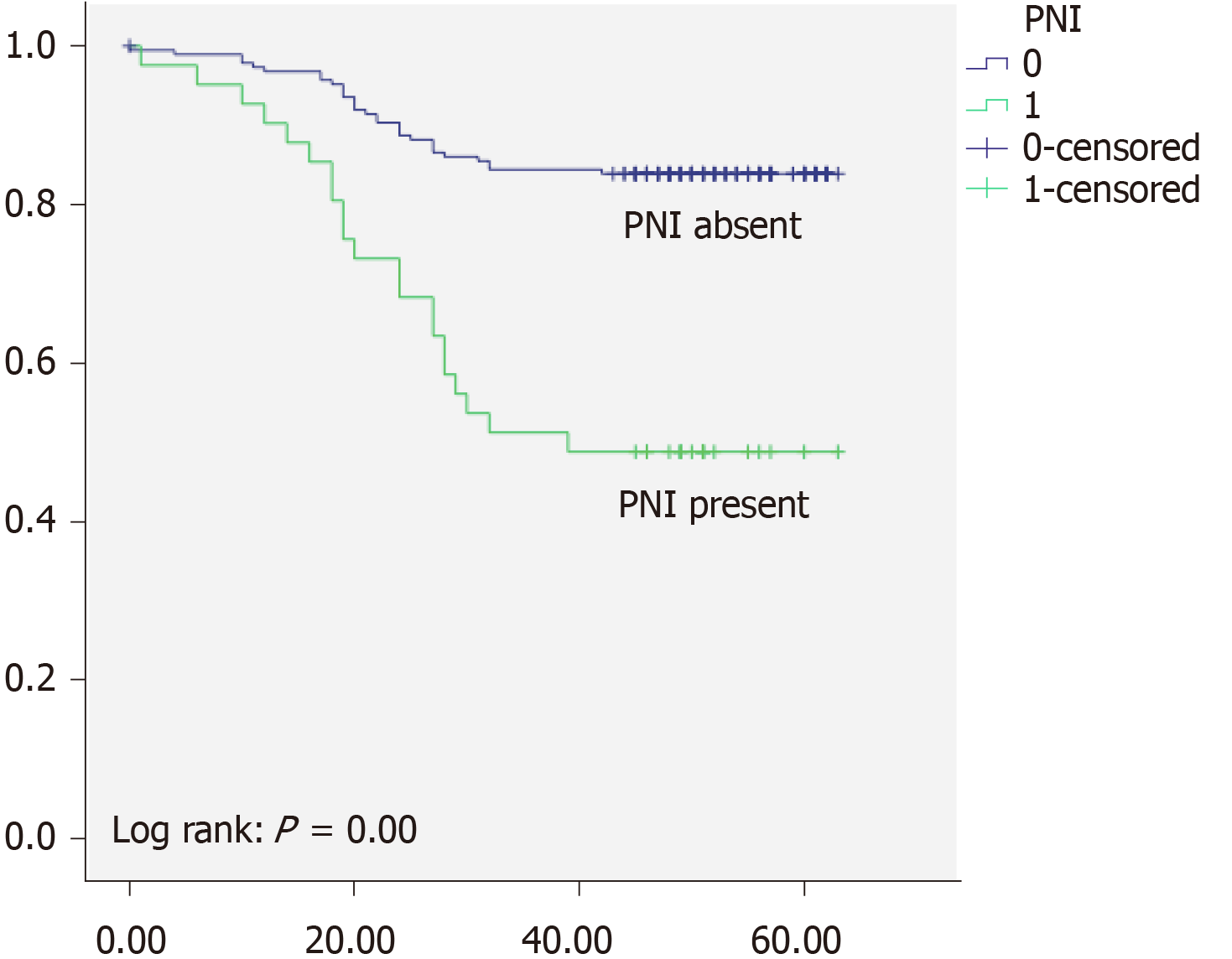

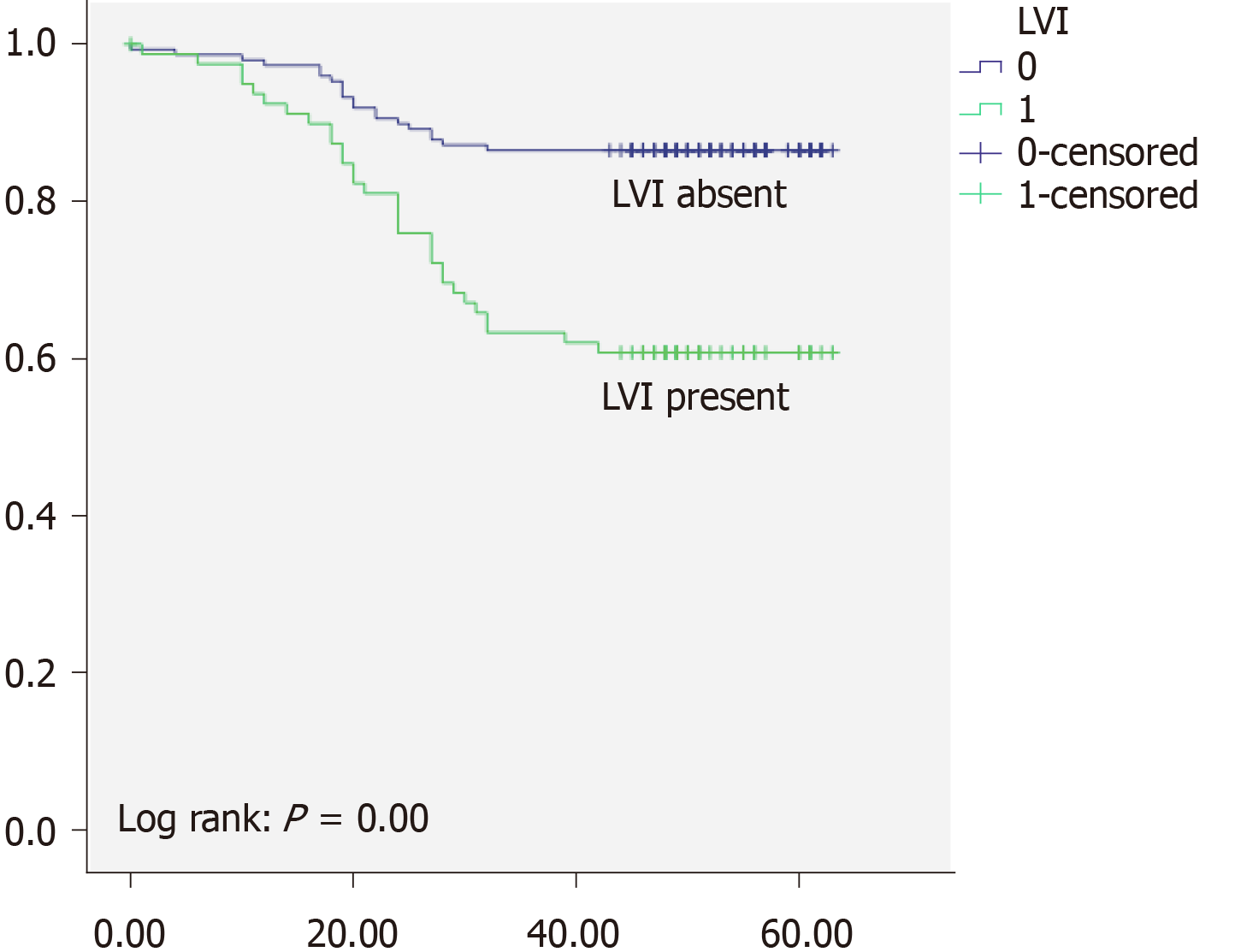

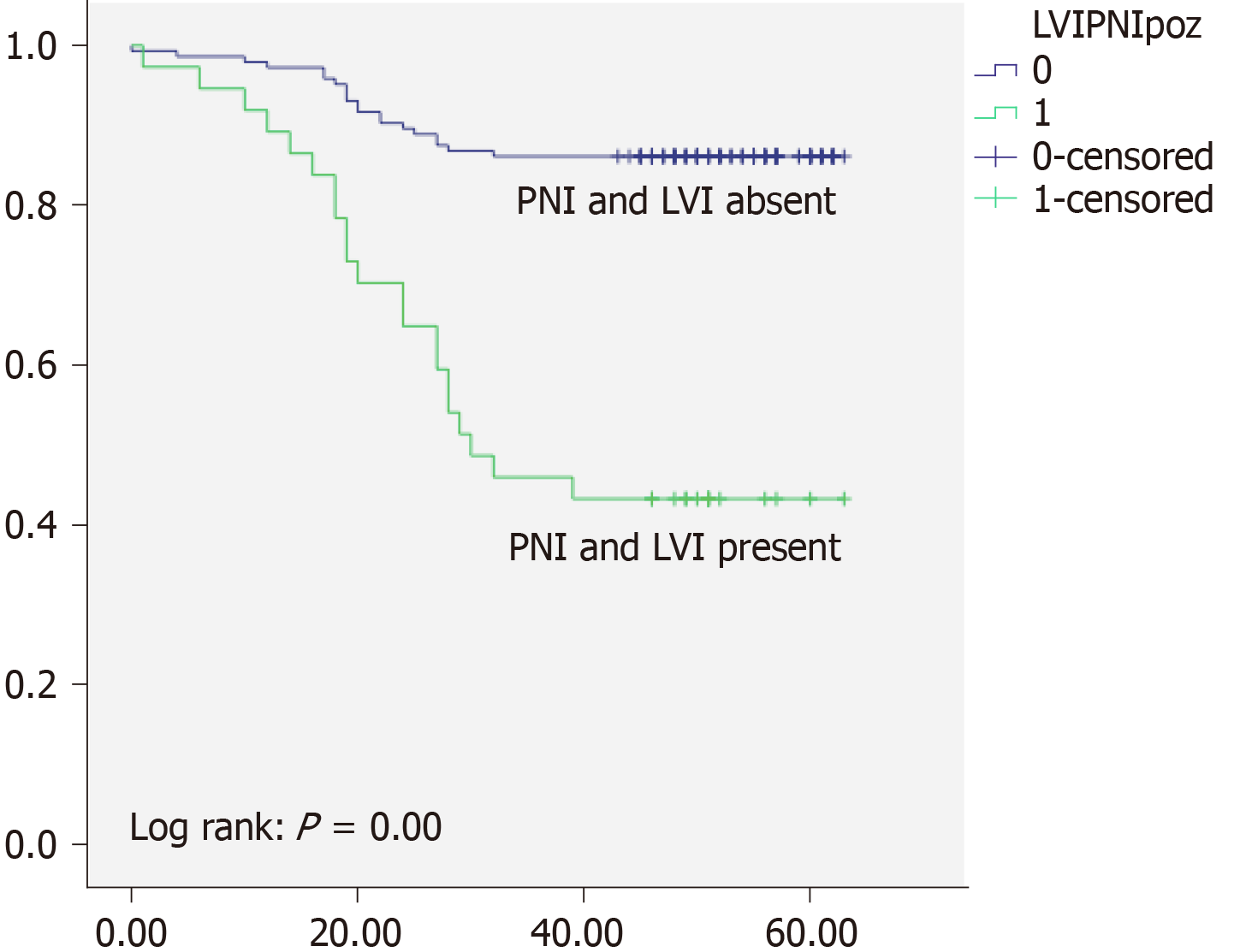

Overall 5-years survival rate was 97% for TNM stage I, 89% for TNM stage II, and 49% for TNM stage III respectively. There was high statistically significant difference regarding OS between different TNM stages (P < 0.05) (Figure 1). Local recurrence was observed in 32 patients (10%), and distant recurrence was found in 45 (15%). Disease free survival was 87% for TNM stage I, 79% for TNM stage II, and 34% for TNM stage III respectively. When we analyzed survival rates with regards to PNI status, we found that patients without PNI had 84% OS and 66% DFS and whereas patients with PNI had OS of 48% and DFS of 34% (Figure 2). Moreover patients without LVI had 87% OS, and 66% DFS while patients with LVI had 61% OS and 34% (Figure 3). There was high statistically significant difference regarding OS and DFS between different LVI and PNI status (P < 0.05). Furthermore when patients were both LVI and PNI positive survival rate was 43% in comparison to both LVI and PNI negative status 86% (P < 0.05) (Figure 4). Cox proportional hazard model was further used to investigate the independent survival prognostic factors. After controlling the age and gender both LVI presence and PNI presence significantly correlated with poor overall survival and disease free survival (P < 0.05). Namely presence of LVI was associated with 3-fold higher risk of lethal outcome (HR = 3.23; 95%CI: 1.800-5.800; P < 0.05) and 2-fold higher risk of disease recurrence (HR = 2.33; 95%CI: 1.094-4.967; P < 0.05). Presence of PNI was associated with almost 4-fold higher risk of lethal outcome (HR = 3.99; 95%CI: 2.231-7.148; P < 0.05), and 6-fold higher risk of disease recurrence (HR = 6.11; 95%CI: 2.651-14.079; P < 0.05). Lethal outcome risk was higher when both PNI and LVI were present (HR = 5.49; 95%CI: 2.889-10.429; P < 0.05).

Previous studies have widely investigated pathways of metastases formation in CRC. Namely, vascular and lymphatic pathways have been acknowledged as common route for distant cancer spreading. However, numerous investigations have highlighted the pathway of cancer spreading trough nerve invasion of cancer cells. Bearing in mind that first step in metastases formation is invasion of vascular and neural structures, LVI and PNI individually as well as combined have been a focus of investigations in different cancer types, including CRC[10]. However limited number of studies investigated influence of both LVI and PNI in early and intermediate stages of RC.

In the available literature presence of LVI ranges from 10% up to almost 90%[11,12]. In comprehensive retrospective analysis of Hogan et al[13] where LVI was observed in both CRC and RC patients, LVI was present in about 30% of the patients with RC. Results of Hogan et al[13] are similar to our own, where LVI was present in 38% of the patients. However, the results of Zhong et al[14] as well as Kim et al[6] reported presence of LVI in 20% and 16% patients, respectively. Wide discrepancies in the presence of LVI could be due to heterogeneity of study population, taking into account that majority of studies included both CRC and RC patients. Moreover, different histopathology methods used in specimen staining could potentially influence detection of LVI. Discrepancies could also be due to differences in interpretation of LVI, as some authors note LVI as lymphatic invasion, or angiolymphatic invasion or venous invasion[15,16].

Hogan et al[13] state that LVI is associated with adverse OS in RC group of patients, although the presence of LVI was higher in colon cancer patients. This furthermore emphasizes the necessity of LVI assessment in RC patients.

In our cohort of patients with LVI had 61% survival rate, while patients without LVI had 87% survival rate. There was high statistically significant difference regarding OS between different LVI statuses. In study of Cho et al[17], LVI was found to be strong prognostic factor for worse OS in RC patients, with 3-fold higher risk of lethal outcome. Results of the Sun et al[7] additionally emphasize the significance of LVI detection in RC patients, where LVI presence was associated with even 4-fold higher risk of poor survival. Results of both studies are in concordance with the results of our investigation, where we have found that patients with LVI have 3-fold higher risk of lethal outcome.

PNI has been a field of investigation in many cancers, firstly head and neck, and later bladder and prostate cancer as well as pancreatic and gastric cancers[18-20]. The importance of PNI detection in the terms of treatment decision is necessary, considering that earlier investigations in patients with CRC have marked PNI as a predictor of poor prognosis[12].

In large study of Song et al[21] presence of PNI was found in 17% of the patients, while Huh et al[12] reported presence of PNI was found in 19% of the patients. Results of our study are in concordance with the results of previous investigations. To be specific, PNI was present in 19% of our patients with RC.

Kinugasa et al[22] reported that patients with PNI had 51% 5-year survival rate compared to PNI absent patients with 80% survival rate. Results of our study are similar to previously reported. In our cohort patients with PNI had survival rate of 48%, and patients without PNI had 84% of 5-year survival rate. The data in available literature demonstrate that OS in CRC as well as RC, differ trough stages, and is dependent from many cofounding factors including LVI and PNI[23]. Namely it has been shown that presence of LVI and PNI is associated with more advanced tumors, as well as poor overall survival. In the study of Zheng et al[24] patients with PNI showed significantly worse survival than those without PNI. In the previously mentioned study of Sun et al[7] patients with PNI had 4.8-fold higher risk of poor survival. Swets et al[25] have marked PNI as a indicator for adjuvant therapy, with presence of PNI associated with 3-fold higher worse survival. Results of our investigation suggest that patients with PNI had almost 4-fold higher risk of lethal outcome, which is in accordance with previously reported. Risk is even higher when both PNI and LVI are present, which is similar to the results of Sun et al[7].

This was a single center study on early and intermediate rectal cancer patients who were all Caucasian, so these were the limitations of our study.

In conclusion results of our study suggest that PNI and LVI individually and combined have significant impact on survival rates of early and intermediate rectal cancer patients. Additional randomized prospective studies are necessary to investigate potential benefits of adjuvant therapy for these patients.

Rectal cancer (RC) accounts about one third of all diagnosed colorectal cancers. Although TNM staging has proven as applicable in very early and late disease stages, accuracy in the intermediary stages of the RC remains controversial. Precise pathological examination is needed in order to determine which patients would benefit from adjuvant therapy. Few previous investigations have focused on correlation of presence of perineural invasion (PNI) or/as well as lymphovascular invasion (LVI) with the cancer-related outcome in RC patients, therefore more studies in this field are needed.

Considering the rising incidence of RC, we have investigated easily applicable and reliable factors that can potentially predict potential outcomes in patients with RC.

We evaluated the clinical significance of PNI as well as LVI in patients with stage I-III RC and further investigated whether these two histopathological features alone and combined affect survival of RC patients.

We have prospectively studied patients with early and intermediate RC. Using Kaplan-Meier method we have analyzed the median survival time, whereas Cox proportional hazards models were used to evaluate the influence of PNI and LVI as prognostic factors in RC patients.

Using Kaplan-Meier analysis for overall survival rate, we have found that both LVI and PNI were associated with lower overall survival rates as well as disease free survival rates (P < 0.01). Moreover when Cox multiple regression model was used, presence of LVI was associated with 3-fold higher risk of lethal outcome and 2-fold higher risk of disease recurrence (P < 0.05). Presence of PNI was associated with almost 4-fold higher risk of lethal outcome and 6-fold higher risk of disease recurrence (P < 0.05).

This study supports the hypothesis that PNI as well as LVI should be carefully and thoroughly examined in the histopathological analysis of RC patients even in early and intermediate disease stages, bearing in mind that such findings could have a great impact on the prognosis. Also patients with both LVI and PNI involvement even in early stages of the disease should not be overlooked, and must be monitored carefully with more frequent and detailed check-ups.

PNI and LVI should be included as obligatory analysis in histopathology reports of RC patients. Additional randomized prospective studies are necessary to confirm these results, and also to investigate other potential prognostic factors in RC patients.

| 1. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13300] [Cited by in RCA: 15624] [Article Influence: 2232.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (11)] |

| 2. | Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Dyba T, Randi G, Bettio M, Gavin A, Visser O, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: Estimates for 40 countries and 25 major cancers in 2018. Eur J Cancer. 2018;103:356-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1625] [Cited by in RCA: 1733] [Article Influence: 216.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Batut DMJ. Health of Population of Serbia. Serbia: Institute of Public Health of Serbia, 2006: 176. |

| 4. | Glynne-Jones R, Wyrwicz L, Tiret E, Brown G, Rödel C, Cervantes A, Arnold D; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:iv263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 38.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mik M, Berut M, Dziki L, Trzcinski R, Dziki A. Right- and left-sided colon cancer - clinical and pathological differences of the disease entity in one organ. Arch Med Sci. 2017;13:157-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kim CH, Yeom SS, Lee SY, Kim HR, Kim YJ, Lee KH, Lee JH. Prognostic Impact of Perineural Invasion in Rectal Cancer After Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy. World J Surg. 2019;43:260-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sun Q, Liu T, Liu P, Luo J, Zhang N, Lu K, Ju H, Zhu Y, Wu W, Zhang L, Fan Y, Liu Y, Li D, Zhu Y, Liu L. Perineural and lymphovascular invasion predicts for poor prognosis in locally advanced rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and surgery. J Cancer. 2019;10:2243-2249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471-1474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5537] [Cited by in RCA: 6610] [Article Influence: 413.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Delibegovic S. Introduction to Total Mesorectal Excision. Med Arch. 2017;71:434-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Roxburgh CS, McMillan DC, Richards CH, Atwan M, Anderson JH, Harvey T, Horgan PG, Foulis AK. The clinical utility of the combination of T stage and venous invasion to predict survival in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2014;259:1156-1165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lim TY, Pavlidis P, Gulati S, Pirani T, Samaan M, Chung-Faye G, Dubois P, Irving P, Heneghan M, Hayee B. Vedolizumab in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Associated with Autoimmune Liver Disease Pre- and Postliver Transplantation: A Case Series. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:E39-E40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Huh JW, Lee JH, Kim HR, Kim YJ. Prognostic significance of lymphovascular or perineural invasion in patients with locally advanced colorectal cancer. Am J Surg. 2013;206:758-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hogan J, Chang KH, Duff G, Samaha G, Kelly N, Burton M, Burton E, Coffey JC. Lymphovascular invasion: a comprehensive appraisal in colon and rectal adenocarcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:547-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhong JW, Yang SX, Chen RP, Zhou YH, Ye MS, Miao L, Xue ZX, Lu GR. Prognostic Value of Lymphovascular Invasion in Patients with Stage III Colorectal Cancer: A Retrospective Study. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:6043-6050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Compton CC, Fielding LP, Burgart LJ, Conley B, Cooper HS, Hamilton SR, Hammond ME, Henson DE, Hutter RV, Nagle RB, Nielsen ML, Sargent DJ, Taylor CR, Welton M, Willett C. Prognostic factors in colorectal cancer. College of American Pathologists Consensus Statement 1999. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:979-994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sibio S, Di Giorgio A, D'Ugo S, Palmieri G, Cinelli L, Formica V, Sensi B, Bagaglini G, Di Carlo S, Bellato V, Sica GS. Histotype influences emergency presentation and prognosis in colon cancer surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2019;404:841-851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cho HJ, Baek JH, Baek DW, Kang BW, Lee SJ, Kim HJ, Park SY, Park JS, Choi GS, Kim JG. Prognostic Significance of Clinicopathological and Molecular Features After Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy in Rectal Cancer Patients. In Vivo. 2019;33:1959-1965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Carr RA, Roch AM, Zhong X, Ceppa EP, Zyromski NJ, Nakeeb A, Schmidt CM, House MG. Prospective Evaluation of Associations between Cancer-Related Pain and Perineural Invasion in Patients with Resectable Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21:1658-1665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zareba P, Flavin R, Isikbay M, Rider JR, Gerke TA, Finn S, Pettersson A, Giunchi F, Unger RH, Tinianow AM, Andersson SO, Andrén O, Fall K, Fiorentino M, Mucci LA; Transdisciplinary Prostate Cancer Partnership (ToPCaP). Perineural Invasion and Risk of Lethal Prostate Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26:719-726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Muppa P, Gupta S, Frank I, Boorjian SA, Karnes RJ, Thompson RH, Thapa P, Tarrell RF, Herrera Hernandez LP, Jimenez RE, Cheville JC. Prognostic significance of lymphatic, vascular and perineural invasion for bladder cancer patients treated by radical cystectomy. Pathology. 2017;49:259-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Song JH, Yu M, Kang KM, Lee JH, Kim SH, Nam TK, Jeong JU, Jang HS, Lee JW, Jung JH. Significance of perineural and lymphovascular invasion in locally advanced rectal cancer treated by preoperative chemoradiotherapy and radical surgery: Can perineural invasion be an indication of adjuvant chemotherapy? Radiother Oncol. 2019;133:125-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kinugasa T, Mizobe T, Shiraiwa S, Akagi Y, Shirouzu K. Perineural Invasion Is a Prognostic Factor and Treatment Indicator in Patients with Rectal Cancer Undergoing Curative Surgery: 2000-2011 Data from a Single-center Study. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:3961-3968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Merkel S, Mansmann U, Papadopoulos T, Wittekind C, Hohenberger W, Hermanek P. The prognostic inhomogeneity of colorectal carcinomas Stage III: a proposal for subdivision of Stage III. Cancer. 2001;92:2754-2759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zheng HT, Shi DB, Wang YW, Li XX, Xu Y, Tripathi P, Gu WL, Cai GX, Cai SJ. High expression of lncRNA MALAT1 suggests a biomarker of poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:3174-3181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Swets M, Kuppen PJK, Blok EJ, Gelderblom H, van de Velde CJH, Nagtegaal ID. Are pathological high-risk features in locally advanced rectal cancer a useful selection tool for adjuvant chemotherapy? Eur J Cancer. 2018;89:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: Serbia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Feng YJ, Petrusel L, Zhou ZH S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Qi LL