Published online Jan 15, 2020. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v12.i1.83

Peer-review started: May 10, 2019

First decision: July 31, 2019

Revised: August 9, 2019

Accepted: September 12, 2019

Article in press: September 12, 2019

Published online: January 15, 2020

Processing time: 237 Days and 11 Hours

Gemcitabine plus platinum is the standard of care first-line treatment for advanced biliary tract cancers (BTC). There is no established second-line therapy, and retrospective reviews report median progression-free survival (PFS) less than 3 mo on second-line therapy. 5-Fluorouracil plus irinotecan (FOLFIRI) is a commonly used regimen in patients with BTC who have progressed on gemcitabine plus platinum, though there is a paucity of data regarding its efficacy in this population.

To assess the efficacy of FOLFIRI in patients with biliary tract cancers.

We retrospectively identified patients with advanced BTC who were treated with FOLFIRI at MD Anderson, University of Michigan and Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville. Data were collected on patient demographics, BTC subtype, response per RECIST v1.1, progression and survival.

Ninety-eight patients were included of which 74 (75%) had metastatic and 24 (25%) had locally advanced disease at the time of treatment with FOLFIRI. The median age was 60 (range, 22-86) years. The number of patients with extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, gall bladder cancer and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma were 10, 17 and 71, respectively. FOLFIRI was used as 1st, 2nd, 3rd or 4th – Nth lines in 8, 50, 36 and 4 patients, respectively. Median duration on FOLFIRI in the entire cohort was 2.2 (range, 0.5-8.4) mo. The median PFS and overall survival were 2.4 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.7-3.1) and 6.6 (95%CI: 4.7-8.4) mo, respectively. Median PFS for patients treated with FOLFIRI in 1st, 2nd, 3rd or 4th – Nth lines were 3.1, 2.5, 2.3 and 1.5 mo, respectively. Eighteen patients received concurrent bevacizumab (n = 13) or EGFR-targeted therapy (n = 5) with FOLFIRI, with a median PFS of 2.7 mo (95%CI: 1.7-5.1).

In this largest multi-institution retrospective review of 98 patients with BTC treated with FOLFIRI, efficacy appears to be modest with outcomes similar to other cytotoxic chemotherapy regimens.

Core tip: We retrospectively analyzed patients with advanced biliary tract cancers treated with 5-fluorouracil plus irinotecan at three institutions, MD Anderson, University of Michigan and Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville. We identified 98 patients with a median age of 60 years, most (72%) of whom had intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Fifty and 36 patients were treated in the second and third-line settings, respectively. The median progression-free survival and overall survival were 2.4 (95%CI: 1.7-3.1) and 6.6 (95%CI: 4.7-8.4) mo, respectively.

- Citation: Mizrahi JD, Gunchick V, Mody K, Xiao L, Surapaneni P, Shroff RT, Sahai V. Multi-institutional retrospective analysis of FOLFIRI in patients with advanced biliary tract cancers. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2020; 12(1): 83-91

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v12/i1/83.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v12.i1.83

Biliary tract cancers (BTCs) are rare but aggressive malignancies that arise from epithelial cells in the bile ducts or gallbladder. BTCs are anatomically classified as intrahepatic and extrahepatic (perihilar and distal) cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), and gallbladder carcinoma (GBCA)[1-3].

In the United States alone, more than 12000 people are estimated to be diagnosed with BTC in 2019[4]. Advanced BTCs are considered aggressive cancers with a reported median overall survival (OS) of approximately 12 mo. Over 85000 people lost their lives to BTC between 1999 and 2014[5], and mortality rates continue to rise[5,6]. It is clear that more effective management strategies are needed to reverse these rising rates, particularly for patients with advanced BTCs. Standard of care first-line therapy for these patients involves multi-agent chemotherapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin[7-9]. In the phase 3 ABC-02 trial published in 2010, gemcitabine and cisplatin was demonstrated to improve median OS to 11.7 mo from 8.1 mo with gemcitabine alone. However, durable response rates are infrequent, and a substantial number of patients progress quickly. Additional strategies and subsequent lines of therapy remain largely investigational with no clear standard at present, although FOLinic acid and Fluorouracil in combination with either OXaliplatin (FOLFOX) or IRInotecan (FOLFIRI) are often used[10-12].

The efficacy of FOLFIRI as a first or second-line treatment has been previously assessed in small retrospective studies. In a single institution review of 17 patients with advanced BTC treated with FOLFIRI as first-line therapy, the authors noted a median progression free survival (PFS) and OS of 2.6 and 6.5 mo, respectively[13]. In another retrospective analysis of 64 patients with advanced BTC treated with either FOLFIRI or XELIRI as second-line therapy, Brieau et al[10] observed a similar median PFS and OS of 2.6 and 6.2 mo, respectively. Additionally, a smaller retrospective analysis of five BTC patients treated with either FOLFIRI or FOLFOX as second-line therapy reported a median PFS and OS of 4.4 and 6.1 mo, respectively[14].

The primary objective of this retrospective analysis was to identify the efficacy of irinotecan-based regimens in the management of patients with advanced BTC in a larger multi-institutional cohort.

The study was individually approved by the institutional review boards at University of Michigan, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and Mayo Clinic Cancer Center at Jacksonville. The informed consent was waived for this HIPAA compliant retrospective study. The eligibility criteria included patients aged 18 years or older with pathologic confirmation of BTC and advanced unresectable or metastatic disease on imaging. Eligible subjects must have received irinotecan-based systemic chemotherapy. Patients with ICD9 and ICD10 diagnosis codes for BTC were retrospectively identified at each institution with at least one encounter between January 2007 and October 2017. Data were collected on patient demographics, subtype of BTC, response per RECIST v1.1, progression and survival. In addition, genomic analysis data were also collected, when available.

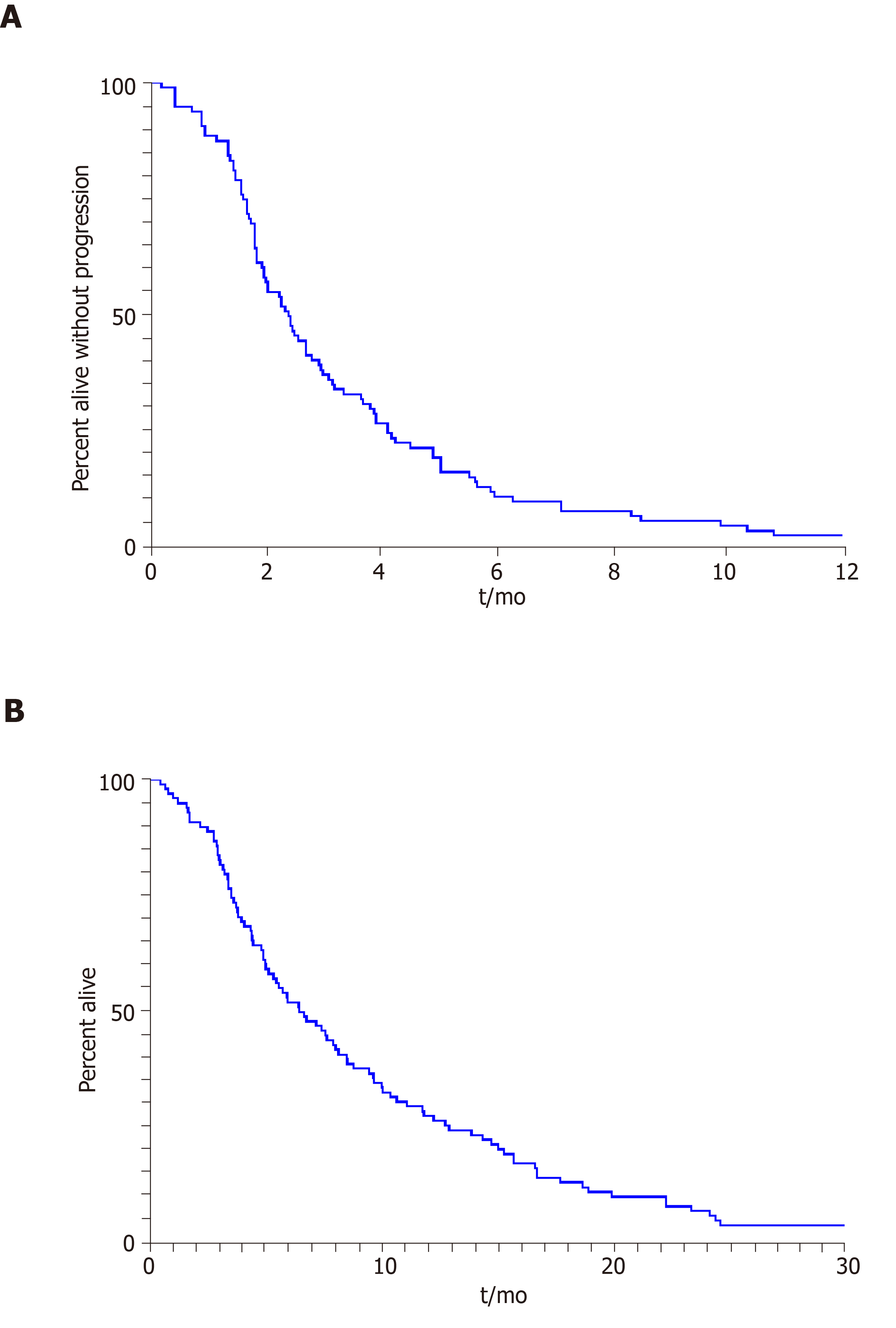

Descriptive statistics such as mean, standard deviation, median and range, frequency and percentage were used to summarize patient characteristics. The Kaplan-Meier method was applied to estimate survival outcomes (Figure 1), i.e., OS and PFS, and the log rank test was used for comparison of these outcomes between subgroups of patients. The OS time was calculated as the time period from the date of the treatment start to the date of death or to the date of the last follow-up for patients alive, and patients alive were censored for the analysis of OS. The PFS time was calculated as the time period from the date of start of treatment to the date of progression or death, whichever occurred first; and patients alive and without progression were censored to the date of the last follow-up. SAS software v9.4 (SAS institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States) and Splus software v8.2 (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA, Unites States).

A total of 98 consecutive patients who met the eligibility criteria were included in the analysis. The median age was 60 years (range, 22-86 years), and 46 (46.9%) subjects were women. Sixty-one patients were identified at MD Anderson, 26 at University of Michigan, and 11 at Mayo Clinic Cancer Center in Jacksonville. Seventy-four (75%) patients had distant metastases at the time of treatment with FOLFIRI, while 24 (25%) had locally advanced disease. The majority of patients had intrahepatic CCA (n = 71), compared with 17 with GBCA and 10 with extrahepatic CCA. The patient baseline characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

| Characteristic | Value |

| Total, n | 98 |

| Age in yr, median (range) | 60 (22-86) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 46 (47) |

| Male | 52 (53) |

| Institution, n (%) | |

| MD Anderson Cancer Center | 61 (62) |

| University of Michigan | 26 (27) |

| Mayo Clinic Cancer Center | 11 (11) |

| Stage at Treatment with FOLFIRI, n (%) | |

| Locally advanced | 24 (25) |

| Metastatic | 74 (75) |

| Subtype of BTC, n (%) | |

| Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma | 10 (10) |

| Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma | 71 (72) |

| Gallbladder carcinoma | 17 (17) |

| Line of Therapy, n (%) | |

| First | 8 (8) |

| Second | 50 (51) |

| Third | 36 (37) |

| Fourth or greater | 4 (4) |

| Irinotecan-based regimen, n (%) | |

| FOLFIRI | 77 (79) |

| FOLFIRI + bevacizumab | 13 (13) |

| FOLRIRI + anti-EGFR | 5 (5) |

| FOLFIRINOX | 2 (2) |

| FOLFIRI + nab-paclitaxel | 1 (1) |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | |

| 0 | 11 (11) |

| 1 | 48 (49) |

| 2 | 3 (3) |

| 3 | 2 (2) |

| Not documented | 34 (35) |

The median duration on FOLFIRI, or FOLFIRI-containing regimens, was 2.2 mo (range, 0.5 to 8.4), and the median PFS was 2.4 mo (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.7-3.1) for the entire cohort. The median PFS for patients treated with FOLFIRI as 1st, 2nd, 3rd or 4th – Nth line therapy was 3.1 (95%CI: 1.4-4.8), 2.4 (95%CI: 1.8-3.7), 2.3 (95%CI: 1.5-3.1) and 1.5 (95%CI: 0.9-2.0) mo, respectively. The median OS for patients treated with FOLFIRI as 1st, 2nd, 3rd or 4th – Nth line therapy was 12.3 (95%CI: 5.6-23.4), 7.7 (95%CI: 4.9-10.5), 5.0 (95%CI: 3.6-7.3) and 7.5 (95%CI: 5.2-9.8) mo, respectively. The median OS for the cohort was 6.6 mo (95%CI: 4.7-8.4) from start of therapy. The best overall response rate was 9.8% per RECIST v1.1 with a disease control rate of 45.1%.

Thirteen patients received vascular endothelial growth factor targeted therapy with bevacizumab, and five patients received anti-epidermal growth factor receptor therapy with erlotinib (n = 4) and panitumumab (n = 1) concurrently with FOLFIRI. Patients in both of these groups of patients exhibited a median PFS of 2.7 mo.

There was no statistically significant difference in median PFS for patients with locally advanced disease when compared to those with distant metastases (3.2 vs 2.1 mo, P = 0.16) at the time of FOLFIRI treatment. There was a trend towards prolonged median OS for patients with locally advanced cancer compared to those with distant metastases (9.3 vs 5.6 mo, P = 0.08) (Table 2).

| Variable | Median PFS (95%CI) | P value | Median OS (95%CI) | P value |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 2.4 (1.6–3.6) | 0.65 | 6.6 (4.5–9.9) | 0.65 |

| Male | 2.3 (1.5–3.4) | 6.9 (4.6–10.3) | ||

| Subtype of BTC | ||||

| Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma | 3.7 (1.5–18.9) | 0.14 | 8.0 (1.8–22.3) | 0.61 |

| Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma | 2.3 (1.9-2.8) | 6.5 (4.5–9.7) | ||

| Gallbladder carcinoma | 2.1 (1.8–3.7) | 6.5 (5.2–10.1) | ||

| Stage at treatment with FOLFIRI | ||||

| Locally Advanced | 3.2 (2.0–5.2) | 0.16 | 9.3 (5.9–14.7) | 0.08 |

| Metastatic | 2.1 (1.3–3.3) | 5.6 (3.5–8.8) | ||

| Line of therapy | ||||

| First | 3.1 (1.4–4.8) | 0.24 | 12.3 (5.6–23.4) | 0.08 |

| Second | 2.4 (1.8–3.7) | 7.7 (4.9–10.5) | ||

| Third | 2.3 (1.5–3.1) | 5.0 (3.6–7.3) | ||

| Fourth or greater | 1.5 (0.9–2.0) | 7.5 (5.2–9.8) | ||

| ECOG performance status | ||||

| 0 or 1 | 2.5 (2.0–3.1) | 0.44 | 7.7 (5.6–11.9) | 0.03 |

| 2 or greater | 1.5 (0.8–4.9) | 2.9 (1.7–8.6) | ||

| Undocumented | 2.1 (1.6–3.4) | 5.3 (3.8–8.2) | ||

| Genomic analysis | ||||

| KRAS | ||||

| Wildtype | 2.4 (1.1–5.1) | 0.12 | 11.8 (5.5–25.4) | 0.06 |

| Mutant | 3.7 (1.7–8.0) | 7.5 (3.5–16.1) | ||

| FGFR | ||||

| Wildtype | 2.5 (1.0–6.0) | 0.29 | 8.0 (3.3–19.4) | 0.56 |

| Fusion | 4.3 (1.8–10.5) | 13.4 (5.5–32.2) | ||

| IDH1 | ||||

| Wildtype | 2.7 (1.2–6.0) | 0.02 | 10.8 (4.9–23.9) | 0.14 |

| Mutant | 2.1 (0.9–4.6) | 4.1 (2.3–11.1) |

Thirty-four (35%) of the patients included in the study had genomic profiling of their BTC completed, including five with extrahepatic CCA, 27 with intrahepatic CCA and two with GBCA. The genomic profiling results are summarized in Table 3. The most frequent alterations identified included mutations in TP53 (35.3%), IDH1 and IDH2 (29.4%) and KRAS (20.6%) genes. FGFR2 fusions were identified in four patients with intrahepatic CCA and two patients with extrahepatic CCA, however, the IDH1 and IDH2 mutations were restricted to the intrahepatic subtype.

| Total patients profiled, n = 34 | Cholangiocarcinoma | Gallbladder carcinoma, n = 2 (6%) | |

| Extrahepatic, n = 5 (15%) | Intrahepatic, n = 27 (79%) | ||

| Mutation | n (% of profiled) | n (% of profiled) | n (% of profiled) |

| TP53 | - | 10 (37) | 2 (100) |

| IDH1 | - | 8 (30) | - |

| KRAS | 1 (20) | 6 (22) | - |

| FGFR2 | 2 (40) | 4 (15) | - |

| IDH2 | - | 2 (7) | - |

| PBRM1 | - | 2 (7) | - |

| BAP1 | - | 2 (7) | - |

| NF1 | - | 1 (4) | 1 (50) |

| ARID1A | - | 1 (4) | 1 (50) |

| CDKN2A | - | - | 1 (50) |

| MET | - | 1 (4) | - |

| CCND1 | - | 1 (4) | - |

| PBX1 | - | 1 (4) | - |

| MYC | - | 1 (4) | - |

| RB1 | - | 1 (4) | - |

| MAP3K1 | - | 1 (4) | - |

| S76 | - | 1 (4) | - |

| SPTA1 | - | 1 (4) | - |

| RET | - | 1 (4) | - |

| ALK | - | 1 (4) | - |

| ATM | - | 1 (4) | - |

| CCNE1 | - | 1 (4) | - |

| GNAS | - | 1 (4) | - |

| SMAD4 | - | 1 (4) | - |

| PIK3CA | - | 1 (4) | - |

| PIK3CB | - | 1 (4) | - |

| PTEN | - | 1 (4) | - |

| PALB2 | - | 1 (4) | - |

| ARID2 | - | 1 (4) | - |

| BRCA2 | - | 1 (4) | - |

| BRAF | - | 1 (4) | - |

| MDM2 | 1 (20) | - | - |

| FRS2 | 1 (20) | - | - |

In this multi-institution retrospective study, FOLFIRI, or FOLFIRI-containing regimens had modest efficacy with a median PFS of 2.4 mo and OS of 6.6 mo in patients with advanced unresectable or metastatic BTC. To our knowledge, this is the largest analysis of outcomes with FOLFIRI in BTCs. Expectedly, patients treated with FOLFIRI earlier in the course of their therapy tended to have longer PFS (P = 0.53), likely due to use of other 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) containing regimens prior to FOLFIRI and development of multi-drug resistance. Additionally, patients with locally advanced stage may have longer PFS (3.2 vs 2.1 mo; P = 0.16) compared to those with distant metastasis.

The majority of the patients included in our analysis had intrahepatic CCA (72%). This subtype of BTC may be associated with better outcomes compared to extrahepatic CCA and GBCA[15], which could potentially bias our results. However, a difference in survival was not seen in our patients based on subtype of BTC, though the sample size of patients with extrahepatic CCA and GBCA was small.

The survival outcomes we describe are comparable to those reported by Brieau et al[10] and Moretto et al[13] utilizing FOLFIRI and similar to published data regarding other chemotherapy regimens, such as FOLFOX in this patient population[16,17]. FOLFOX has been evaluated in multiple prospective studies as second-line therapy with a reported time to progression of 3.1 mo in a 37 patient phase II trial from China[18] and a PFS of 3.9 mo in a 66 patient observational study from Japan[19]. A retrospective analysis of 144 patients with BTCs treated with second-line chemotherapy (70% regimens 5-FU based) at a single institution in Germany found an overall response rate of 9.7% with a disease control rate of 33.6% and median OS of 9.9 mo[20]. An additional retrospective study of 18 patients from an institution in Chile showed a median PFS and OS of 3.2 and 4.6 mo, respectively[17]. There are several other clinical trials accruing patients for second-line therapy, including the phase Ib/II trial evaluating the combination of 5-FU, folinic acid and nanoliposomal irinotecan in conjunction with an anti-PD1 antibody nivolumab (BilT-03)[21].

In the subgroup of 18 patients who were treated concurrently with either anti-EGFR or anti-vascular endothelial growth factor targeted therapy, there did not appear to be a clinical benefit of the additional drug, though this was a small cohort. This is in contrast to a single institution analysis from France of 13 patients with metastatic intrahepatic CCA treated with FOLFIRI with bevacizumab as second-line therapy that reported a best overall response rate of 38.4%, median PFS of 8 mo and OS of 20 mo[22].

We identified no significant correlation between specific somatic mutations and patient outcomes or response to FOLFIRI, though this conclusion is limited by the small number of patients in our study. Recently, the most promising therapeutic advances in BTC have resulted from the identification and targeting of actionable driver somatic mutations. Multiple phase II clinical trials have yielded encouraging results by taking advantage of driver mutations such as FGFR, IDH1, IDH2 and BRAF[23-26]. However, most patients with BTCs do not harbor mutations that are currently targetable, limiting the benefits of these recent advances to only a select cohort.

Given the lack of other standard therapies for patients with BTCs who have progressed on first-line therapy, our results indicate that FOLFIRI may indeed have a role in these patients. The results of our study further emphasize the need for more effective treatment options for patients with advanced unresectable or metastatic BTCs after failure of first-line systemic chemotherapy, especially in absence of actionable driver mutations.

Advanced biliary tract cancers (BTC) are aggressive malignancies without an established standard of care after progression on first-line combination chemotherapy with gemcitabine plus cisplatin. Fluoropyrimidine-based therapies, such as 5-fluorouracil plus either oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) or irinotecan (FOLFIRI) are commonly used in this setting. There is limited data on the efficacy of such regimens in patients with BTCs, particularly in the patients who have progressed on first-line therapy.

There is a significant need for evidence-based treatment of patients with advanced BTCs who have previously progressed of first-line systemic chemotherapy. Only small, primarily single-institution analyses have been published about the role of FOLFIRI in this population. We sought to combine the experiences of multiple institutions to provide the largest dataset with this regimen.

Our study assessed the efficacy of FOLFIRI in patients with BTC by measuring progression-free survival and overall survival.

We retrospectively identified patients with advanced, unresectable BTC who were treated with FOLFIRI at three institutions: MD Anderson, University of Michigan and Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville. We collected data on survival, response per RECIST v1.1, patient demographics and tumor characteristics.

Ninety-eight patients were included in our analysis, most of whom were treated in the second and third-line setting. Median duration on FOLFIRI was 2.2 mo. Median progression-free survival was 2.4 mo (95%CI: 1.7-3.1), and median overall survival was 6.6 mo (95%CI: 4.7-8.4).

The efficacy of FOLFIRI for patients with BTCs appears to be modest with survival outcomes that are similar to historical controls of other retrospectively examined second-line cytotoxic therapy options.

Based on this multi-institutional analysis, FOLFIRI seems to have a limited role in the treatment of patients with BTCs, though there are no prospective studies that have assessed this regimen in this patient population. The recently reported results of the randomized phase III ABC-06 trial demonstrating an increase in OS with modified FOLFOX plus active symptom control compared to active symptom control alone likely makes this a more appealing treatment option for most patients who have progressed on gemcitabine plus cisplatin.

| 1. | Bridgewater J, Galle PR, Khan SA, Llovet JM, Park JW, Patel T, Pawlik TM, Gores GJ. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2014;60:1268-1289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 862] [Cited by in RCA: 1122] [Article Influence: 93.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bridgewater JA, Goodman KA, Kalyan A, Mulcahy MF. Biliary Tract Cancer: Epidemiology, Radiotherapy, and Molecular Profiling. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016;35:e194-e203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wistuba II, Gazdar AF. Gallbladder cancer: lessons from a rare tumour. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:695-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 332] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13300] [Cited by in RCA: 15625] [Article Influence: 2232.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (11)] |

| 5. | Yao KJ, Jabbour S, Parekh N, Lin Y, Moss RA. Increasing mortality in the United States from cholangiocarcinoma: an analysis of the National Center for Health Statistics Database. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16:117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Khan SA, Toledano MB, Taylor-Robinson SD. Epidemiology, risk factors, and pathogenesis of cholangiocarcinoma. HPB (Oxford). 2008;10:77-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in RCA: 343] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, Madhusudan S, Iveson T, Hughes S, Pereira SP, Roughton M, Bridgewater J; ABC-02 Trial Investigators. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine vs gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1273-1281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2617] [Cited by in RCA: 3338] [Article Influence: 208.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (15)] |

| 8. | Okusaka T, Nakachi K, Fukutomi A, Mizuno N, Ohkawa S, Funakoshi A, Nagino M, Kondo S, Nagaoka S, Funai J, Koshiji M, Nambu Y, Furuse J, Miyazaki M, Nimura Y. Gemcitabine alone or in combination with cisplatin in patients with biliary tract cancer: a comparative multicentre study in Japan. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:469-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 570] [Cited by in RCA: 586] [Article Influence: 36.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Park JO, Oh DY, Hsu C, Chen JS, Chen LT, Orlando M, Kim JS, Lim HY. Gemcitabine Plus Cisplatin for Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer: A Systematic Review. Cancer Res Treat. 2015;47:343-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Brieau B, Dahan L, De Rycke Y, Boussaha T, Vasseur P, Tougeron D, Lecomte T, Coriat R, Bachet JB, Claudez P, Zaanan A, Soibinet P, Desrame J, Thirot-Bidault A, Trouilloud I, Mary F, Marthey L, Taieb J, Cacheux W, Lièvre A. Second-line chemotherapy for advanced biliary tract cancer after failure of the gemcitabine-platinum combination: A large multicenter study by the Association des Gastro-Entérologues Oncologues. Cancer. 2015;121:3290-3297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chun YS, Javle M. Systemic and Adjuvant Therapies for Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Control. 2017;24:1073274817729241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lamarca A, Palmer DH, Wasan HS, Ross PJ, Ma YT, Arora A, Falk S, Gillmore R, Wadsley J, Patel K, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, Waters JS, Hobbs C, Barber S, Ryder D, Ramage J, Davies LM, Bridgewater JA, Valle JW, on behalf of the Advanced Biliary Cancer (ABC) Working Group. ABC-06 | A randomised phase III, multi-centre, open-label study of active symptom control (ASC) alone or ASC with oxaliplatin / 5-FU chemotherapy (ASC+mFOLFOX) for patients (pts) with locally advanced / metastatic biliary tract cancers (ABC) previously-treated with cisplatin/gemcitabine (CisGem) chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2019;4003. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Moretto R, Raimondo L, De Stefano A, Cella CA, Matano E, De Placido S, Carlomagno C. FOLFIRI in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic or biliary tract carcinoma: a monoinstitutional experience. Anticancer Drugs. 2013;24:980-985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fiteni F, Jary M, Monnien F, Nguyen T, Beohou E, Demarchi M, Dobi E, Fein F, Cleau D, Fratté S, Nerich V, Bonnetain F, Pivot X, Borg C, Kim S. Advanced biliary tract carcinomas: a retrospective multicenter analysis of first and second-line chemotherapy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lamarca A, Ross P, Wasan HS, Hubner RA, McNamara MG, Lopes A, Manoharan P, Palmer D, Bridgewater J, Valle JW. Advanced intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: post-hoc analysis of the ABC-01, -02 and -03 clinical trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rogers JE, Law L, Nguyen VD, Qiao W, Javle MM, Kaseb A, Shroff RT. Second-line systemic treatment for advanced cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2014;5:408-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Leal JL, Roa JC, Jarufe N, Madrid J, Ibanez C, Herrera ME, Garrido M, Nervi B. Second-line FOLFOX chemotherapy in patients with metastatic gallbladder cancer and cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:322-322. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | He S, Shen J, Sun X, Liu L, Dong J. A phase II FOLFOX-4 regimen as second-line treatment in advanced biliary tract cancer refractory to gemcitabine/cisplatin. J Chemother. 2014;26:243-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dodagoudar C, Doval DC, Mahanta A, Goel V, Upadhyay A, Goyal P, Talwar V, Singh S, John MC, Tiwari S, Patnaik N. FOLFOX-4 as second-line therapy after failure of gemcitabine and platinum combination in advanced gall bladder cancer patients. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2016;46:57-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Schweitzer N, Kirstein MM, Kratzel AM, Mederacke YS, Fischer M, Manns MP, Vogel A. Second-line chemotherapy in biliary tract cancer: Outcome and prognostic factors. Liver Int. 2019;39:914-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center. Phase Ib/II trial of Nal-irinotecan and nivolumab as second-line treatment in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer. [accessed 2019 Apr 25]. In: ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): U.S. National Library of Medicine. Available from: https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03785873 ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03785873. |

| 22. | Guion-Dusserre JF, Lorgis V, Vincent J, Bengrine L, Ghiringhelli F. FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as a second-line therapy for metastatic intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:2096-2101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lowery MA, Abou-Alfa GK, Burris HA, Janku F, Shroff RT, Cleary JM, Azad NS, Goyal L, Maher EA, Gore L, Hollebecque A, Beeram M, Trent JC, Jiang L, Ishii Y, Auer J, Gliser C, Agresta SV, Pandya SS, Zhu AX. Phase I study of AG-120, an IDH1 mutant enzyme inhibitor: Results from the cholangiocarcinoma dose escalation and expansion cohorts. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:4015-4015. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Javle M, Lowery M, Shroff RT, Weiss KH, Springfeld C, Borad MJ, Ramanathan RK, Goyal L, Sadeghi S, Macarulla T, El-Khoueiry A, Kelley RK, Borbath I, Choo SP, Oh DY, Philip PA, Chen LT, Reungwetwattana T, Van Cutsem E, Yeh KH, Ciombor K, Finn RS, Patel A, Sen S, Porter D, Isaacs R, Zhu AX, Abou-Alfa GK, Bekaii-Saab T. Phase II Study of BGJ398 in Patients With FGFR-Altered Advanced Cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:276-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 510] [Cited by in RCA: 536] [Article Influence: 67.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hollebecque A, Lihou C, Zhen H, Abou-Alfa GK, Borad M, Sahai V, Catenacci DVT, Murphy A, Vaccaro G, Paulson A, Oh D-Y, Féliz L. Interim results of fight-202, a phase II, open-label, multicenter study of INCB054828 in patients (pts) with previously treated advanced/metastatic or surgically unresectable cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) with/without fibroblast growth factor (FGF)/FGF receptor (FGFR) genetic alterations. Ann Oncol. 2018;29. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wainberg ZA, Lassen UN, Elez E, Italiano A, Curigliano G, Braud FGD, Prager G, Greil R, Stein A, Fasolo A, Schellens JHM, Wen PY, Boran AD, Burgess P, Gasal E, Ilankumaran P, Subbiah V. Efficacy and safety of dabrafenib (D) and trametinib (T) in patients (pts) with BRAF V600E–mutated biliary tract cancer (BTC): A cohort of the ROAR basket trial. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:187-187. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cao ZF, Frena A S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Liu MY