Published online Oct 16, 2014. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v6.i10.499

Revised: July 31, 2014

Accepted: September 4, 2014

Published online: October 16, 2014

Processing time: 125 Days and 8.5 Hours

AIM: To ascertain fine needle aspiration (FNA) techniques by endosonographers with varying levels of experience and environments.

METHODS: A survey study was performed on United States based endosonographers. The subjects completed an anonymous online electronic survey. The main outcome measurements were differences in needle choice, FNA technique, and clinical decision making among endosonographers and how this relates to years in practice, volume of EUS-FNA procedures, and practice environment.

RESULTS: A total of 210 (30.8%) endosonographers completed the survey. Just over half (51.4%) identified themselves as academic/university-based practitioners. The vast majority of respondents (77.1%) identified themselves as high-volume endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) (> 150 EUS/year) and high-volume FNA (> 75 FNA/year) performers (73.3). If final cytology is non-diagnostic, high-volume EUS physicians were more likely than low volume physicians to repeat FNA with a core needle (60.5% vs 31.2%; P = 0.0004), and low volume physicians were more likely to refer patients for either surgical or percutaneous biopsy, (33.4% vs 4.9%, P < 0.0001). Academic physicians were more likely to repeat FNA with a core needle (66.7%) compared to community physicians (40.2%, P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION: There is significant variation in EUS-FNA practices among United States endosonographers. Differences appear to be related to EUS volume and practice environment.

Core tip: Endoscopic ultrasound with fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) has become a mainstay in the evaluation of various gastrointestinal diseases. However, little is known about the preferred FNA techniques used by practitioners. The aim of this survey study was to evaluate the practice patterns of a heterogeneous group of endosonographers. Subjects were queried in regards to training, experience, case volume, and preferences regarding FNA needle choice and techniques used. The results demonstrate a moderate variation in EUS-FNA practices among those endosonographers who responded to the survey (n = 210). Significant differences appear to be related to EUS volume and practice environment.

- Citation: DiMaio CJ, Buscaglia JM, Gross SA, Aslanian HR, Goodman AJ, Ho S, Kim MK, Pais S, Schnoll-Sussman F, Sethi A, Siddiqui UD, Robbins DH, Adler DG, Nagula S. Practice patterns in FNA technique: A survey analysis. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 6(10): 499-505

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v6/i10/499.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v6.i10.499

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with fine needle aspiration (FNA) has become a mainstay for the diagnosis of a variety of gastrointestinal diseases. Despite its widespread use, little is known about the preferred FNA techniques utilized by most practitioners. Numerous studies have attempted to address the relative importance of needle size, use of a stylet, use of suction, number of needle passes, and the use of rapid on-site evaluation of cytology (ROSE) as it relates to the effect on diagnostic yield of FNA[1,2]. Despite these studies, there is no consensus as to which techniques are preferred and most frequently practiced. In addition, it is unclear as to whether the level of experience of the endosonographer and the environment in which they practice has an impact on FNA technique. This information is relevant as differences in FNA technique may allow for analysis of one’s own EUS practice, and afford an opportunity to assess if optimal techniques are being implemented for maximal diagnostic yield. The aim of this study was to ascertain current FNA technique by endosonographers with varying levels of experience from various practice environments across the United States.

This study was designed as an electronic survey. Institutional review board approval was granted to conduct this research. Gastroenterology physicians who perform EUS-FNA in the United States were identified from a list of providers assembled by a major FNA needle manufacturer (Cook Medical Inc., Winston-Salem, NC). E-mail addresses were then queried via the membership directories of three major gastroenterology societies (American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, American Gastroenterological Association, and American College of Gastroenterology). Subjects were contacted through e-mail via a commercially-available electronic survey tool, and were asked to complete an anonymous electronic survey assessing their FNA practice. The survey was designed to be completed in less than 5 min. Emails requesting participation were sent out every two weeks to subjects who did not respond to the initial invitation to participate in the survey. There were no incentive programs utilized to increase the response rate. The survey was sent out between October 2011 and November 2011, and was closed after 5 wk.

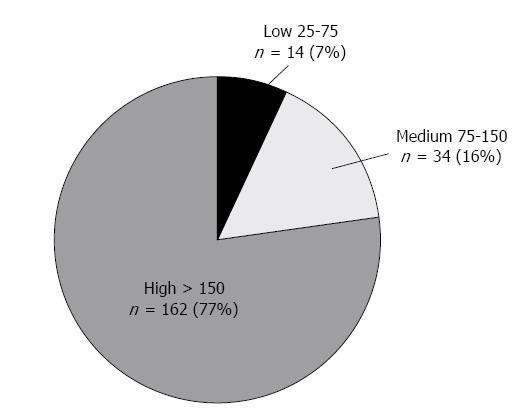

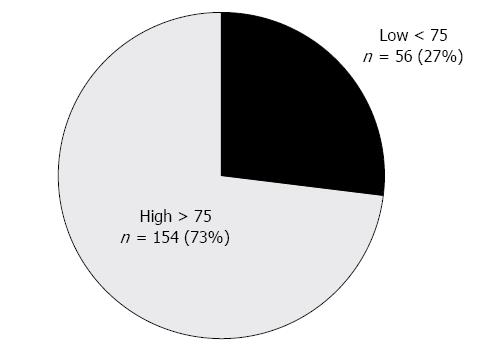

High-volume EUS practitioners were defined as those physicians performing greater than 150 EUS examinations per year, medium volume defined as between 75-150 EUS exams per year, while low-volume EUS practitioners were defined as those physicians performing less than 75 EUS examinations per year. Recognizing that not all EUS practitioners perform FNA, we further stratified EUS practitioners by volume of FNA performed per year. High-volume FNA was defined as greater than 75 FNA per year, whereas low-volume was less than 75 FNA per year.

When defining FNA techniques, the term “needle pass” referred to one direct insertion of the needle across the GI lumen into the target lesion. The term “needle throw” was defined as one to-and-fro motion with the needle once it is already inside the target lesion.

Results of the survey were tabulated. Surveys with incomplete demographic information were excluded from the analysis. Blank responses to individual questions were excluded from the analysis of that question; no imputations were made for missing data. χ2 analysis was used to assess associations between demographic variables and survey responses. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA).

A total of 681 EUS-FNA practitioners were identified and contacted; a total of 210 (30.8%) completed the survey (Table 1).

| Category | n (%) |

| When training was completed | |

| < 3 yr ago | 38 (18.1) |

| 3-10 yr ago | 96 (45.7) |

| > 10 yr ago | 76 (36.2) |

| Fourth year fellowship | |

| Yes | 116 (55.2) |

| No | 94 (44.8) |

| Practice environment | |

| Academic/University-Based | 108 (51.4) |

| Community Practice | 102 (48.6) |

| Annual EUS volume | |

| 25-75 | 14 (6.7) |

| 75-150 | 34 (16.2) |

| > 150 | 162 (77.1) |

| Annual FNA volume | |

| < 75 | 56 (26.7) |

| > 75 | 154 (73.3) |

Most practitioners completed their GI fellowship training 3-10 years ago (n = 96; 45.7%) or more than 10 years ago (n = 76; 36.2%), while a small portion completed fellowship training within the past 3 years (n = 38; 18.1%). More than half of the respondents (n = 116; 55.2%) had received formal training in EUS during a 4th year advanced endoscopy fellowship. Just over half (n = 108; 51.4%) identified themselves as academic/university-based practitioners, while 48.6% (n = 102) were community-based.

The vast majority of respondents (n = 162; 77.1%) identified themselves as high-volume EUS practitioners (> 150 EUS/year), compared to 16.2% (n = 34) medium-volume, with the remainder performing less than 75 EUS exams per year (Figure 1). With regards to FNA volume, 73.3% (n = 154) of respondents identified themselves as high-volume FNA practitioners (> 75 FNA/year) (Figure 2).

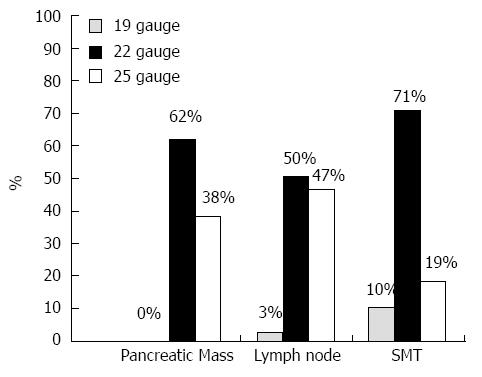

When performing FNA of a solid pancreatic mass, the majority of respondents preferred to use a 22 gauge needle as their initial choice of needle (n = 130; 62%), compared to the 25 gauge needle (n = 80; 38.0%) or 19 gauge needle (0%, Figure 3). When performing FNA of a submucosal mass lesion in the esophagus, stomach, or rectum, the majority of respondents preferred the 22 gauge needle as their initial choice of needle (n = 149; 71.0), compared to the 25 gauge needle (n = 39; 18.6%), or the 19 gauge needle (n = 22; 10.5%, Figure 3). When performing FNA of a lymph node (mediastinal, abdominal, peri-rectal), respondents chose either the 22 gauge needle (n =106; 50.5%) or the 25 gauge needle (n = 98; 46.7%), with only 2.9% (n = 6) choosing a 19 gauge needle (Figure 3).

The vast majority of respondents reported an average of 3-5 needle passes (n = 173; 82.4%) when performing FNA of a solid pancreatic mass, while 13.3% (n = 28) reported performing 6 or more passes and 4.3% (n = 9) perform 1-2 passes.

For lymph nodes, 66.7% (n = 140) of respondents perform 3-5 needle passes on average, while 31.4% (n = 66) perform only 1-2 passes, and 1.9% (n = 4) perform 6 or more passes.

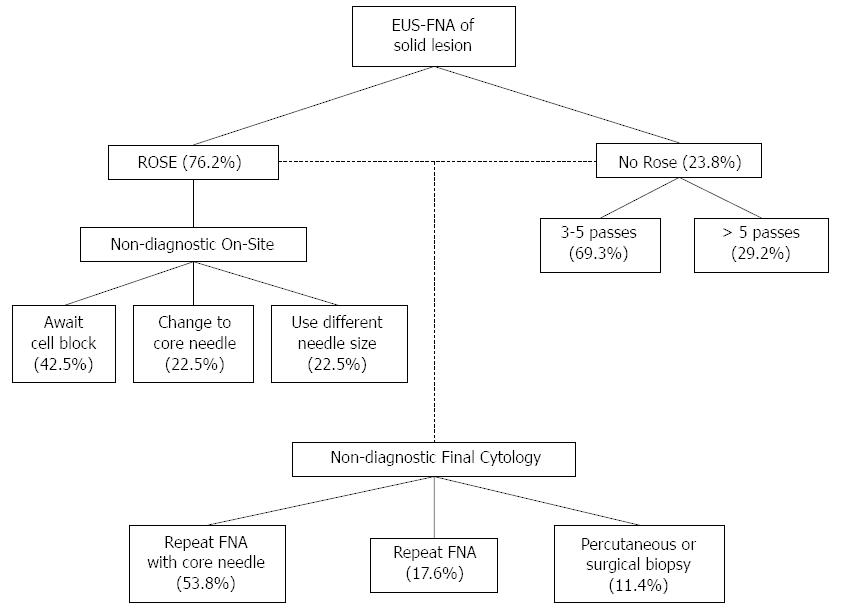

If ROSE is not available, over two-thirds of endosonographers (n = 140 out of 203 responses; 69.3%) will perform 3-5 passes, while 29.2% (n = 59) will perform 6 or more passes (Figure 4).

Once the needle tip is in the target lesion, 48.6% (n = 102) of respondents perform 10-20 needle throws, while 37.6% (n = 79) perform 6-10 needle throws, 8.6% (n = 18) perform more than 20 needle throws, and 5.2% (n = 11) perform 5 or less needle throws.

A stylet is used on the initial needle pass by 91.4% (n = 192) of practitioners. On subsequent needle passes, the stylet is used by 81.8% (n = 171/209) of practitioners.

The routine use of suction was favored by 85.5% (n = 177/207) of respondents for FNA of solid lesions, and 66.8% (n = 140) of respondents for FNA of lymph nodes.

The vast majority of respondents (n = 160; 76.2%) utilize ROSE when performing EUS-FNA (Figure 4). Of those practitioners using ROSE, 38.1% (n = 61) report that the specimen is read by an attending cytopathologist, 24.4% (n = 39) report that a cytotechnician examines the specimen, and 36.9% (n = 59) report that the specimen is analyzed by both. One subject (0.6%) reported self-review of the specimen as the main type of ROSE.

If inadequate specimen is obtained as determined by ROSE, 42.5% (n = 68) of practitioners will cease performing further tissue acquisition and will await results of the cell block, while 22.5% (n = 36) change to core biopsy needle, 14.4% (n = 23) will change to a larger gauge FNA needle, and 8.1% (n = 13) will change to a smaller gauge FNA needle (Figure 4).

If a bloody specimen is obtained, 48.6% (n = 102) will continue FNA but without suction, while 23.8% (n = 50) will continue FNA but without any change in technique or needle size, 14.8% (n = 31) will continue FNA with both a change in needle size and without suction, and 3.3% (n = 7) will continue FNA with change in needle size only.

If the final cytology is non-diagnostic, 53.8% (n = 113) of subjects will repeat EUS-FNA and will consider using a core biopsy needle, 17.6% (n = 37) will simply repeat EUS-FNA, 7.6% (n = 16) will refer patient for a percutaneous biopsy, and 3.8% (n = 8) will refer patient for a surgical biopsy (Figure 4).

Training: When comparing responses based on when training was completed, there was no statistical difference seen on all questions.

If adequate tissue was not obtained as determined by ROSE, those practitioners having completed a 4th year advanced endoscopy fellowship were more likely to switch to a core needle compared to those who did not complete a 4th year fellowship (28.0% vs 14.9%, P = 0.05). For the remainder of the questions, there was no statistically significant difference among the responses.

Practice environment: If the final cytology assessment was deemed non-diagnostic, academic-based physicians were more likely to repeat EUS-FNA and use a core biopsy needle, compared to community-based practitioners (66.7% vs 40.2%, P = 0.00012). For the remainder of the questions, there was no statistically significant difference among the responses.

EUS volume: If adequate tissue was not obtained as determined by ROSE, low/medium volume EUS practitioners (< 150 EUS/year n = 20/35) were more likely to await results of the cell block compared to high-volume EUS practitioners (> 150 EUS/year, n = 40/125) (57.1% vs 32.0%, P = 0.04). High volume practitioners (n = 35) were more likely to utilize a core biopsy needle compared to low/medium volume practitioners (n = 1) (28% vs 2.6%, P = 0.002).

If the final cytology assessment was deemed non-diagnostic, high-volume physicians (n = 98) were more likely than low-volume physicians (n =15) to repeat FNA with a core needle (60.5% vs 31.2%, P = 0.0004). When compared to high-volume EUS physicians, low-volume EUS physicians were more likely to refer patients for a percutaneous biopsy (18.8% vs 4.3%, P = 0.0009) or a surgical biopsy (14.6% vs 0.6%, P = 0.000009). For the remainder of the questions, there was no statistically significant difference among the responses.

FNA volume: If adequate tissue was not obtained as determined by ROSE, low-volume FNA practitioners were more likely to terminate the procedure and await the results of the cell block as compared to high-volume FNA physicians (44.6% vs 27.9%, P = 0.006). High-volume FNA practitioners were more likely to use a core biopsy needle compared to low-volume FNA practitioners (23.4% vs 0%, P = 0.00006).

If the final cytology assessment was deemed non-diagnostic, high-volume FNA physicians were more likely to repeat FNA with a core needle, as compared to low-volume FNA physicians (59.7% vs 37.5%%, P = 0.004). When compared to high-volume FNA physicians, low-volume FNA physicians were more likely to refer to patients for a percutaneous biopsy (16.1% vs 4.5%, P = 0.005) or surgical biopsy (8.9% vs 1.9%, P = 0.02).

In an attempt to gain a snapshot of EUS practices and techniques, this electronic survey was distributed to endosonographers across the entire United States. Our results represent a cross-section of endosonographers as relates to their training, time in practice, and type of practice environment. This study demonstrates that there is variation in EUS-FNA techniques among EUS practitioners. In addition, we gain some insight into the volume of procedures performed, noting that the majority of respondents were considered high-volume, as based on our definition. Interestingly, but perhaps not surprising, a significant number of high volume endosonographers were community-based practitioners, which signifies the growth and acceptance of EUS beyond the tertiary referral center.

This study provides concrete data regarding practice patterns in actual clinical practice across a wide spectrum of endosonographers. For example, the 22-gauge needle appears to be the most popular needle used for FNA of solid pancreatic masses as well as submucosal tumors. This data is a bit surprising, as numerous randomized studies show no statistically significant difference in diagnostic yield between the 25-gauge and 22-gauge needles, but actually a trend towards better yield with the 25-gauge needle[3-5]. Furthermore, it is recognized that the use of the 25-gauge needle may actually pose a benefit when performing FNA of the pancreatic head or uncinate process, due to its flexibility and thus ease of use when compared to a higher gauge needle (1). However, we were not surprised to see that the 19-gauge needle was the least used needle for initial attempt at FNA. Still, despite these studies, 22 gauge needles appear to be overwhelmingly the needle of choice in most situations. Though our study did not address this specifically, we suspect that the associated technical difficulty of using the 19-gauge needle, particularly when performing trans-duodenal FNA for the pancreatic head/uncinate, and potential concerns about increased procedural risk (pancreatitis, bleeding, and perforation) are likely the reason behind this.

Survey responders favored the use of 3-5 needle passes for solid pancreatic mass lesions and for lymph nodes. The majority preferred a high number of needle throws as well (either 6-10 or 10-20). It is very interesting that nearly all responders utilized a stylet on the initial and subsequent FNA attempts, and nearly all used suction when performing FNA of a solid mass lesion. Two-thirds of respondents utilized suction when performing FNA on a lymph node. Numerous randomized trials have concluded that the use of a stylet increases the bloodiness of a specimen and ultimately does not improve the diagnostic yield in FNA[6-9]. Similarly, the use of suction has not been shown to enhance diagnostic yield in two randomized trials[10,11].

The ability to perform ROSE is perhaps the most important determinant of diagnostic yield when performing EUS-FNA. A number of studies have demonstrated that utilization of ROSE is associated with a significantly higher diagnostic yield, lower rate of indeterminate or unsatisfactory samples, and decreased number of needle passes[12-17]. Just over three quarters of respondents utilized ROSE when performing EUS-FNA. Interestingly, there was no difference in the utilization of ROSE between academic providers and those who considered themselves community practice based.

Perhaps the most relevant data from this study is the analysis of practice patterns amongst practitioners when a non-diagnostic specimen is obtained. Roughly one-half of respondents will repeat an EUS-FNA and consider obtaining a core biopsy at that time. Approximately 10% of respondents will not repeat EUS, but rather refer patients for either a percutaneous or surgical biopsy. Upon sub-group analysis, it appears that those practitioners who were either academic based, completed a 4th year advanced endoscopy fellowship, or were performed high volume EUS-FNA were significantly more likely to repeat an EUS-FNA and consider obtaining core biopsy. Low-volume practitioners, who were community based, were less likely to repeat endoscopic attempts at tissue acquisition and were more likely to refer for percutaneous or surgical biopsy. Knowing the overall safety and efficacy of EUS-FNA in general, this data may present an opportunity for low-volume and/or community based practitioners to re-evaluate their practice patterns when encountering a non-diagnostic specimen.

The main strength of our study is the novel attempt by our group to ascertain EUS practice patterns among a variety of endosonographers with diverse training backgrounds, experience, and practice environments. The high response rate (210/681, 30.8%) can purportedly be ascribed to the high level of interest and curiosity on practice patterns among practicing EUS physicians.

There are a number of limitations to our study. One major limitation is that of the inherent nature of survey studies with their associated recall bias. Another major limitation is the use of industry-supplied databases and society member lists to identify US endosonographers. This method most certainly did not identify every endosonographer eligible for participation in the study, and thus may introduce an element of selection bias in our study population. On the other hand, using this method did help identify over 600 eligible practitioners. The decision to use a database provided by a major needle manufacturer was based on the fact that at the time of this study, this company had the largest market share in the FNA needle market place, and was thus most likely to capture the largest number of endosonographers who perform FNA. Another limitation is that we did not inquire as to what region of the US our responders practiced in. There is a tendency for graduating trainees to practice in the region in which they completed their training. Thus, analysis of this aspect may have uncovered regional differences in practice patterns. This survey placed less emphasis on the use of core needle technology. During the time in which this survey was designed and implemented, newer reverse-bevel needle and large-gauge flexible needles were just being introduced into the marketplace, as were innovative changes in FNA technique (e.g., capillary action by “slow pull” technique). Though we do assess utilization of core needles in some of our survey questions, we postulate that in the interim time frame since implementation of this survey, more endosonographers have had experience with these newer needle designs and FNA techniques, and thus we suspect that many endosonographers who have routinely adopted them in practice. Finally, we did not inquire as to each individual endosonographer’s own rate of diagnostic yield and/or accuracy. Although this would be subject to tremendous recall bias, this information would give credence as to whether or not their preferred techniques are effective.

In conclusion, the results of this survey study of United States endosongraphers provides an opportunity for practitioners to examine their practice patterns, and compare their FNA technique to that of their peers. This may allow practitioners to identify areas for further self-education regarding implementation of evidence-based best practices. These results may help define a “standard” or preferred technique and could thus potentially be used as a reference point when designing prospective, comparative trials in EUS-FNA.

Endoscopic ultrasound with fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) has become a mainstay in the evaluation of various gastrointestinal diseases, in particular neoplastic mass lesions, both luminal and extraluminal. Despite its widespread use, little is known about the preferred FNA techniques used by practititioners.

There are various types of FNA needles currently available. The main difference is in the size, or gauge, of the needle. The majority of the published data demonstrates that needle gauge does not seem to impact the success in obtaining sufficient tissue adequate to assess a diagnosis. Some needle types have the ability to obtain “core” biopsies of the target lesion, which allows for pathologic analysis (as opposed to cytologic analysis). Traditional core biopsy needles are cumbersome, and have been proven difficult to use under certain circumstances due to their rigidity and impact on the flexibility of the echoendoscope (e.g., biopsies of the pancreatic head). Newer designs of the core biopsy hold promise in circumventing these issues, but their use in clinical practice remains unproven at this time. The aim of this current study was to assess the preferred FNA techniques and needle preferences among a large group of United States based endosonographers.

The results of this study demonstrate that there is moderate variation in EUS-FNA practices among EUS practitioners. Significant differences appear to be related to the volume of EUS performed by a particular physician, as well as whether they are based at an academic medical center as opposed to a community practice.

The results of this survey study of United States endosongraphers provide an opportunity for practitioners to examine their practice patterns, and compare their FNA technique to that of their peers. This may allow practitioners to identify areas for further self-education regarding implementation of evidence-based best practices. These results may help define a “standard” or preferred technique and could thus potentially be used as a reference point when designing prospective, comparative trials in EUS-FNA.

EUS is an endoscopic procedure whereby a flexible tube with a video camera at its end is inserted through the mouth (or rectum) into the gastrointestinal tract. These scopes are equipped with a special ultrasound transducer at its tip, allowing for the performance of an ultrasound exam from within the gastrointestinal tract. This allows for detailed visualization of the wall layers of various gastrointestinal organs (e.g., esophagus, stomach), as well as visualization of organs and structures immediately adjacent to the wall (e.g., pancreas, lymph nodes). Fine needle aspiration (FNA) is a technique whereby a specially-designed needle is inserted through an accessory channel of the echoendoscope, and inserted directly into a target lesion under direct EUS guidance. The target lesion may be a lesion originating from within the gastrointestinal tract or be in an organ outside of the gastrointestinal tract. Cells obtained from FNA can be examined under the microscope for diagnostic purposes. Core biopsies refer to the ability to obtain “chunks” of tissue from the target lesion, allowing for microscopic analysis of not only cells, but the actual tissue architecture. This technique is often used when attempts at standard FNA have proven unfruitful.

This is an electronic survey of eusonographers in the United States selected from a list provided by Cook Inc. with a response rate of approximately 30%.

| 1. | Varadarajulu S, Fockens P, Hawes RH. Best practices in endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:697-703. |

| 2. | Polkowski M, Larghi A, Weynand B, Boustière C, Giovannini M, Pujol B, Dumonceau JM. Learning, techniques, and complications of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided sampling in gastroenterology: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Technical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2012;44:190-206. |

| 3. | Camellini L, Carlinfante G, Azzolini F, Iori V, Cavina M, Sereni G, Decembrino F, Gallo C, Tamagnini I, Valli R. A randomized clinical trial comparing 22G and 25G needles in endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of solid lesions. Endoscopy. 2011;43:709-715. |

| 4. | Fabbri C, Polifemo AM, Luigiano C, Cennamo V, Baccarini P, Collina G, Fornelli A, Macchia S, Zanini N, Jovine E. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration with 22- and 25-gauge needles in solid pancreatic masses: a prospective comparative study with randomisation of needle sequence. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:647-652. |

| 5. | Siddiqui UD, Rossi F, Rosenthal LS, Padda MS, Murali-Dharan V, Aslanian HR. EUS-guided FNA of solid pancreatic masses: a prospective, randomized trial comparing 22-gauge and 25-gauge needles. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:1093-1097. |

| 6. | Sahai AV, Paquin SC, Gariépy G. A prospective comparison of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration results obtained in the same lesion, with and without the needle stylet. Endoscopy. 2010;42:900-903. |

| 7. | Rastogi A, Wani S, Gupta N, Singh V, Gaddam S, Reddymasu S, Ulusarac O, Fan F, Romanas M, Dennis KL. A prospective, single-blind, randomized, controlled trial of EUS-guided FNA with and without a stylet. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:58-64. |

| 8. | Wani S, Gupta N, Gaddam S, Singh V, Ulusarac O, Romanas M, Bansal A, Sharma P, Olyaee MS, Rastogi A. A comparative study of endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration with and without a stylet. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2409-2414. |

| 9. | Wani S, Early D, Kunkel J, Leathersich A, Hovis CE, Hollander TG, Kohlmeier C, Zelenka C, Azar R, Edmundowicz S. Diagnostic yield of malignancy during EUS-guided FNA of solid lesions with and without a stylet: a prospective, single blind, randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:328-335. |

| 10. | Wallace MB, Kennedy T, Durkalski V, Eloubeidi MA, Etamad R, Matsuda K, Lewin D, Van Velse A, Hennesey W, Hawes RH. Randomized controlled trial of EUS-guided fine needle aspiration techniques for the detection of malignant lymphadenopathy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:441-447. |

| 11. | Puri R, Vilmann P, Săftoiu A, Skov BG, Linnemann D, Hassan H, Garcia ES, Gorunescu F. Randomized controlled trial of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle sampling with or without suction for better cytological diagnosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:499-504. |

| 12. | Klapman JB, Logrono R, Dye CE, Waxman I. Clinical impact of on-site cytopathology interpretation on endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1289-1294. |

| 13. | Chang KJ, Katz KD, Durbin TE, Erickson RA, Butler JA, Lin F, Wuerker RB. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:694-699. |

| 14. | Erickson RA, Sayage-Rabie L, Beissner RS. Factors predicting the number of EUS-guided fine-needle passes for diagnosis of pancreatic malignancies. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:184-190. |

| 15. | Hikichi T, Irisawa A, Bhutani MS, Takagi T, Shibukawa G, Yamamoto G, Wakatsuki T, Imamura H, Takahashi Y, Sato A. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of solid pancreatic masses with rapid on-site cytological evaluation by endosonographers without attendance of cytopathologists. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:322-328. |

| 16. | Alsohaibani F, Girgis S, Sandha GS. Does onsite cytotechnology evaluation improve the accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy? Can J Gastroenterol. 2009;23:26-30. |

| 17. | Iglesias-Garcia J, Dominguez-Munoz JE, Abdulkader I, Larino-Noia J, Eugenyeva E, Lozano-Leon A, Forteza-Vila J. Influence of on-site cytopathology evaluation on the diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) of solid pancreatic masses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1705-1710. |

P- Reviewer: Chen JQ, Farmer AD, Ooi LL S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN