Published online Oct 16, 2014. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v6.i10.493

Revised: July 21, 2014

Accepted: September 4, 2014

Published online: October 16, 2014

Processing time: 115 Days and 4.7 Hours

AIM: To investigate whether out-patient based endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) for colon polyps ≤ 10 mm is safe.

METHODS: Between January 2004 and December 2012, a total of 3015 EMR cases conducted in 1320 patients were retrospectively reviewed. The factors contributing delayed hemorrhage were analyzed. We calculated the probability of delayed bleeding after stratifying conditions of specific risk factors.

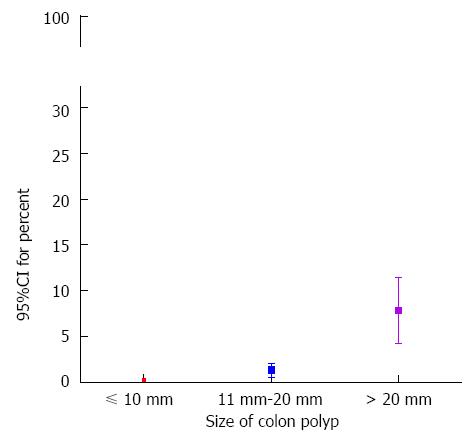

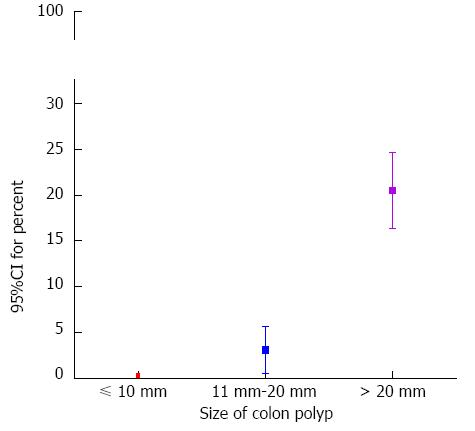

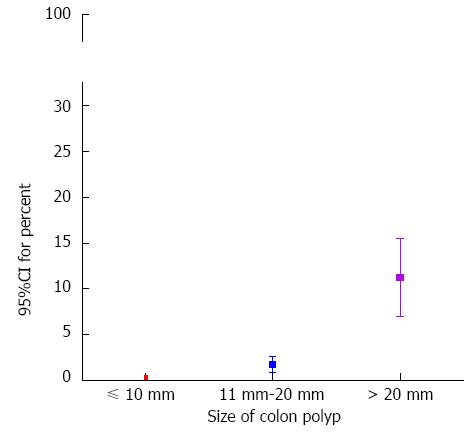

RESULTS: The size of the polyp (95%CI: 1.096-1.164, P < 0.001) and patients with chronic renal failure (95%CI: 1.856-45.106, P = 0.007) were identified as independent risk factors for delayed bleeding in multivariate analysis. 95%CI for percent of delayed bleeding according to polyp size was determined for the following conditions: size ≤ 10 mm, 0.05%-0.43%; 20 mm ≥ size > 10 mm, 0.54%-2.08%; size > 20 mm, 4.22%-11.41%. 95%CI was determined for the risk of serious immediate bleeding for a polyp ≤ 10 mm was 0.10%-0.56%. Finally, 95%CI for percent of incomplete resection was 0.07%-0.49% in polyps ≤ 10 mm.

CONCLUSION: It seems acceptable to perform outpatient-based EMR for colon polyps ≤ 10 mm.

Core tip: There has been a belief that it is safe to perform outpatient-based endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) for a colon polyp ≤ 10 mm. We found out that the risk of delayed bleeding was 0.05% to 0.43% and that the risk of serious immediate bleeding was 0.10% to 0.56% in polyps ≤ 10 mm. From these results, we induced the conclusion that outpatient-based EMR for polyps no more than 10 mm can be performed without serious concern.

- Citation: Kim HH, Kim SE, Cho EJ. What can be the criteria of outpatient-based endoscopic resection for colon polyp? World J Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 6(10): 493-498

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v6/i10/493.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v6.i10.493

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), by snare polypectomy for a pedunculated type or by injection and cutting for a sessile type, is the most common method for removing colon polyps[1] and is widely performed in many clinical fields, from small private clinics to tertiary hospitals. EMR technique should be focused on efficient removal and minimal complication[2]. The most frequent complication is bleeding[3]. Bleeding can be categorized as either immediate or delayed depending on the onset time. Immediate bleeding just after the procedure can be easily managed with recent advancing endoscopic technology and hemostasis equipment[4-6], but delayed hemorrhages causes more serious problem because of unpredictable onset and occurrence after hospital discharge[3,7]. Several research studies showed that locations and the types of polyp could be risk factors for delayed bleeding[4,7,8]. However, the size of the polyp was determined to be the most reliable factor for delayed bleeding[8-11]. Although many endoscopists believe that it is safe to perform outpatient-based EMR for a polyp no more than 10 mm, no definite report about the possibility of delayed bleeding associated with specific conditions of alleged risk factors has been published. In this study, we calculated the possibility of delayed bleeding according to specific situations of risk factors to understand conditions in which outpatient-based EMR can be performed.

We retrospectively reviewed all of the patients that underwent an EMR for a colon polyp between January 2004 and January 2013 at the Gospel Hospital, Kosin University College of Medicine. The institutional review board approved the study protocol. Patients with submucosal tumors, hereditary polyposis syndrome, and inflammatory bowel disease such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, were excluded. Endoscopic submucosal dissection cases were also excluded because we wanted to focus on understanding the safety and efficacy of EMR.

Two conditions were used to define delayed bleeding in the outpatient setting. The first condition was when the patient experienced more than one episode of hematochezia at least one hour after EMR. The second condition was identifiable evidence of hemorrhage from an EMR site; this was established to differentiate delayed bleeding from blood passing during EMR. Immediate serious bleeding was defined as bleeding which required hemostatic clipping (Easy clips; Olympus Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) just after EMR. Histological complete resection was defined when there was no tumor involvement at horizontal and vertical margins. A complete endoscopic resection was defined when en bloc resection was achieved.

Patients were instructed to discontinue the use of anticoagulant or anti-platelet therapy at least 5 to 7 d before endoscopic procedures. The patient’s blood count and coagulation laboratory were measured. Patients were recommended to have a 72 h-fiber-free diet and an 8 h-4-L polyethylene glycol solution to prepare colonoscopy. 25-50 mg of meperidine (Demerol®) was administered intravenously for reducing pain during the colonoscopy. Conscious sedation colonoscopy was performed with 0.05-0.07 mg/kg of initial midazolam, an additional 1-3 mg of midazolam was injected at the discretion of the practitioner if the patient expressed pain.

The procedure was performed with electronic video colonoscopes (types Q260AL and H260AI; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Electrosurgery was performed using ICC 200 (ErbeElektromedizin GmbH, Tübingen, Germany) or a VIO 300D APC2 (ErbeElektromedizin GmbH, Tübingen, Germany). Fours killed endoscopists, each with at least 5 year-experiences with EMR, performed the procedures. Snare polypectomy without submucosal injection was performed for pedunculated polyps. Open snare was placed around the stalk of a pedunculated polyp and was gently grasped. After snare excision, the colon was expanded again to visualize the resection area. For sessile polyps, submucosal injections were performed. The injection solution was composed of saline and epinephrine (1:100000). Injection volume usually ranged from 5 cc to 30 cc. Close observation was applied to each lesion during and after submucosal injection for excluding the presence of a non-lifting sign. EMR was canceled if there was a non-lifting sign. After then, a biopsy was performed and the patient was transferred to surgical unit. En bloc EMR was regarded as complete endoscopic resection of a lesion, and piecemeal EMR was defined when multiple snaring was used. Hot biopsy forceps (FD-1U-1 or FD-1U-2, Olympus Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) were applied to ablate the possible bleeding foci in EMR-related ulcers. If there was serious immediate bleeding, hemostatic clips were applied to control the bleeding and prevent possible delayed bleeding. After EMR, all patients were hospitalized for at least 18 h, and they revisited the outpatient clinic 7 to 14 d after discharge for histologic assessment and to report delayed bleeding or other discomfort.

All resected tissue was collected by a basket or through the suction channel. The size of each polyp was measured. Vienna criteria was applied for histological diagnosis of colorectal neoplasms[12]. Reconstruction of separated specimens was performed to evaluate the horizontal and vertical margins. All resected specimens were evaluated histologically at low-power and high-power magnification using light microscopy.

Reported cases of hematochezia after EMR were confirmed by an attending physician by assessing blood on a digital rectal examination. To check the lesions and to stop bleeding, an emergent colonoscopy was always performed. When an EMR site of delayed bleeding was identified, hemostasis was performed immediately. Clipping was done to control large bleeding or non-bleeding vessels, and hot biopsy forceps was performed for coagulating small vessels or locations where placing hemostatic clips was difficult due to tissue consolidation.

The risk factors for delayed bleeding were analyzed in the view of the patients’ condition, polyp characteristics, and the procedure. Patient-related factors included age, sex, comorbidities, and the use of antiplatelet agents or anticoagulants. The factors related with the characteristics of polyp such as size, location, shape, and pathologic result were investigated. The size of the polyp was measured and compared with the size of the biopsy forceps. The polyp shapes were categorized as sessile or pedunculated. The polyp locations within cecum, ascending colon, and transverse colon were classified as right colon, and the others were regarded as left colon. Based on pathologic reports, the polyps were differentiated as adenocarcinoma, adenoma, or others. Laboratory evaluation before EMR included platelet count, prothrombin time, and activated partial thromboplastin time. Procedure-related factors included en bloc vs piecemeal resection and the presence of serious, immediate bleeding followed by hemostatic clipping.

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Analysis System software for Windows (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States). Depending on the presence of delayed bleeding, the patient characteristic distributions were analyzed using T-test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables, whereas the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test were used to analyze categorical variables. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05, and if there was more than one predictor with a significant difference by univariate analysis, multivariate analysis using a logistic regression model was planned. Furthermore, we planned to calculate 95%CI or proportion to understand the possible risk of specific factors in conditioned situations.

Data were investigated for 3015 polyps, from 1320 patients who were treated by EMR during a 9-year period. The clinical data and demographics of patients and colon polyp characteristics are presented in Table 1. The mean (± SD) age of the patients was 59.6 ± 10.4 years. The mean (± SD) polyp size was 11.1 ± 6.8 mm, and the most common location was the sigmoid colon, which was identified in 817 cases (25.9%). The pedunculated type occurred in 18.2% (550 cases), and 3.0% (89 cases) of investigated polyps were carcinomas. Ten cases showed submucosal invasion. Piecemeal resection was performed for 130 cases (4.3%). There was serious bleeding which required clipping just after EMR in 78 cases (2.6%). Delayed bleeding occurred in 25 cases (0.8%). The mean onset of delayed bleeding was 9.9 ± 0.4 h. Perforation was observed in six cases (0.2%), and all cases were successfully managed by clips. Prophylactic hemostatic clipping was done for 345 (11.4%) EMR sites in order to prevent possible delayed bleeding.

| n = 3015 | |

| Age, mean ± SD, yr | 59.6 ± 10.4 |

| Male | 1771 (70.0) |

| Comorbidity | |

| Hypertension | 564 (18.7) |

| Cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease | 389 (12.9) |

| Chronic renal failure | 23 (0.8) |

| Liver cirrhosis | 75 (2.5) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 157 (5.2) |

| Cancer history | 353 (11.7) |

| Anti-coagulants and anti-platelets | |

| Aspirin | 253 (8.3) |

| Clopidogrel | 57 (1.9) |

| Warfarin | 43 (1.4) |

| Size of lesion, mean ± SD, mm | 11.1 ± 6.8 |

| Locations | |

| Right side colon | 1296 (43.0) |

| Cecum | 109 (3.6) |

| Ascending colon | 805 (26.7) |

| Transverse colon | 382 (12.7) |

| Left side colon | 1719 (57.0) |

| Descending colon | 346 (11.5) |

| Sigmoid colon | 817 (25.9) |

| Rectum | 556 (18.4) |

| Morphologic classification | |

| Pedunculated type | 550 (18.2) |

| Piecemeal resection | 130 (4.3) |

| Pathologic complete resection | 2956 (98.0) |

| Horizontal margin involvement | 31 (1.0) |

| Vertical margin involvement | 10 (0.3) |

| Serious immediate bleeding1 | 78 (2.6) |

| Prophylactic hemostatic clipping | 345 (11.4) |

| Delayed bleeding | 25 (0.8) |

| Spurting, n | 2 |

| Oozing, n | 13 |

| Clots with or without vessel exposure, n | 10 |

| Onset of delayed post-EMR bleeding, mean ± SD (range), h | 9.9 ± 0.4 |

| (7-72) | |

| Perforation | 6 (0.2) |

| Histology | |

| Adenoma | 2357 (78.2) |

| Tubular adenoma | 2026 (67.2) |

| Tubulovillous adenoma | 233 (7.7) |

| Villous adenoma | 99 (3.3) |

| Serrated adenoma | 66 (2.2) |

| Carcinoma | 89 (3.0) |

| Submucosal invasive carcinoma | 10 (0.3) |

| Hyperplastic polyp | 413 (13.6) |

| Others | 90 (3.0) |

There were no differences between the delayed bleeding and uneventful groups in age, sex, and pre-EMR laboratory results. The size of the polyp was much greater in the delayed bleeding group (25.8 ± 11.6 vs 11.0 ± 6.6; P < 0.001). The pedunculated-type polyp was more frequently observed in the delayed bleeding group (P = 0.003). Piecemeal resection and serious immediate bleeding were more frequently noticed in the delayed bleeding group (P = 0.001 and P = 0.025). Patients with chronic renal failure showed significant correlation with delayed bleeding (P = 0.015). There were no significant differences in the locations or histologic types of the polyps. A comparison of the delayed bleeding group and the uneventful group are presented in Table 2.

| Delayed bleeding n = 25 | Uneventful group n = 2990 | P value | |

| Age, mean ± SD, yr | 58.4 ± 10.1 | 59.6 ± 10.4 | 0.646 |

| Male | 15 (60.0) | 1756 (58.7) | 0.898 |

| Laboratory before EMR | |||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.2 ± 1.4 | 13.66 ± 1.8 | 0.187 |

| Platelet, × 103 count/mm3 | 60.5 ± 12.1 | 71.9 ± 1.3 | 0.81 |

| Prothrombin time, INR | 0.984 ± 0.067 | 0.989 ± 0.528 | 0.785 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time, s | 33.8 ± 4.4 | 34.9 ± 23.2 | 0.665 |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Hypertension | 5 (20.0) | 559 (18.7) | 0.800 |

| Cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease | 5 (20.0) | 384 (12.8) | 0.362 |

| Chronic renal failure | 2 (8.0) | 21 (0.7) | 0.015 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 1 (4.0) | 74 (2.5) | 0.131 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 (12.0) | 154 (5.1) | 0.140 |

| Cancer history | 3 (12.0) | 350 (11.7) | 1.000 |

| Anti-coagulants and anti-platelets | |||

| Aspirin | 3 (12.0) | 250 (8.4) | 1.000 |

| Clopidogrel | 1 (4.0) | 56 (1.9) | 0.381 |

| Warfarin | 0 (0.0) | 43 (1.4) | 1.000 |

| Size of lesion, mean ± SD, mm | 25.8 ± 11.6 | 11.0 ± 6.6 | < 0.001 |

| Locations | |||

| Right side colon1 | 8 (32.0) | 1288 (43.1) | 0.314 |

| Morphologic classification | |||

| Pedunculated | 11 (44.0) | 539 (18.0) | 0.003 |

| Piecemeal resection | 6 (24.0) | 124 (4.1) | 0.001 |

| Pathologic complete resection | 25 (100.0) | 2954 (79.9) | 1.000 |

| Horizontal margin involvement | 0 (0.0) | 31 (1.0) | 1.000 |

| Vertical margin involvement | 0 (0.0) | 10 (0.3) | 1.000 |

| Serious immediate bleeding2 | 3 (12.0) | 75 (2.5) | 0.025 |

| Prophylactic hemostatic clipping | 4 (16.0) | 341 (11.4) | 0.319 |

| Histology | |||

| Adenoma | 23 (92.0) | 2337 (78.2) | 0.140 |

| Carcinoma | 1 (4.0 ) | 88 (18.4) | 0.529 |

| Hyperplastic polyp | 1 (4.0) | 412 (13.8) | 0.240 |

| Others | 0 (0.0) | 90 (3.0) | 1.000 |

Logistic regression used for multivariate analysis revealed that size [Odds ratio (OR) = 1.129, 95%CI: 1.096-1.164, P < 0.001] was an independent risk factor for delayed bleeding (Table 3). Furthermore, chronic renal failure was revealed to independently increase the delayed bleeding (OR = 9.150, 95%CI: 1.856-45.106, P = 0.007).

95%CI for percent of delayed bleeding in this study was 0.05% to 0.43% (3/2061) in polyps that were no more than 10 mm in size (Figure 1). 95%CI for percent of delayed bleeding was between 0.54% and 2.08% (8/754) as the polyp size was more than 10 mm and no more than 20 mm. In the situation that the polyp size was more than 20 mm, 95%CI for percent of delayed bleeding increased dramatically, 4.22%-11.41% (14/200).

95%CI for percent of serious immediate bleeding in this study was 0.10% to 0.56% (5/2061) in polyps that were no more than 10 mm in size (Figure 2). 95%CI for percent of serious immediate bleeding was between 2.80% to 5.62% (30/754). The condition that the polyp size was over 10 mm and no more than 20 mm. As the polyp size was more than 20 mm, 95%CI for percent of serious immediate bleeding increased enormously, 16.37%-27.70% (43/200).

95%CI for percent of incomplete resection was 0.07% to 0.49% (4/2061) when the polyp size was no more than 10 mm (Figure 3). As the size of polyp increased, the 95%CI for percent of incomplete resection increased exponentially: 20 mm ≥ Size > 10 mm 0.82%-2.59% (11/754) and Size > 20 mm, 6.97%-15.52% (21/200).

Our study confirmed that polyp size is the substantial risk factor for delayed bleeding which was discussed in previous reports[8-11]. The risk increased by 12.9% (95%CI: 1.096-1.164) per mm increase in diameter; this result was similar to previous investigations[10,11]. The type of polyp, whether sessile or pedunculated, was not a risk factor for delayed bleeding in the present study like other literature[7,9,13,14]. Histologic findings and location did not influence the occurrence of delayed bleeding either.

We calculated the risk of delayed bleeding according to the polyp size because we needed to determine the size of polyps that can be removed by outpatient-based EMR. The risk of delayed bleeding was 0.05% to 0.43% when the polyp size was no more than 10 mm. Serious immediate bleeding causes the procedure to be unstable and can require a patient hospitalized for close observation. In our investigation, serious immediate bleeding occurred in 2.6% (78/3015) of all cases, and this frequency was in the range of a previous report, 1.5% to 2.8%[15]. The risk of serious immediate bleeding was 0.10% to 0.56% in polyps ≤ 10 mm. In our perspective, the risk of delayed bleeding and the risk of immediate bleeding were so low that we were able to conclude outpatient-based EMR for polyps no more than 10 mm can be performed without serious concern.

Contrasting to polyps ≤ 10 mm, outpatient-based EMR for larger polyps can be challenging because of relatively high risk of delayed bleeding and immediate serious bleeding. The risk of delayed bleeding and serious immediate bleeding went beyond 2% and 5% in polyps between 10 mm and 20 mm. The risk rockets when the polyp size was over 20 mm; the risk of delayed bleeding went over 11%, and the risk of serious immediate bleeding exceeded 25%. Considering these results, we suggest doing EMR for patients with polyps no less than 20 mm in size with in-patient setting. We recommend meticulous prophylactic bleeding control for EMR site when polyps are more than 10 mm and no more than 20 mm. Furthermore, it would be beneficial to stress the possibility of hospitalization, if out-patient based EMR should be performed.

We calculated the efficacy of EMR according to polyp sizes. The risk of incomplete resection of a polyp ≤ 10 mm was 0.07% to 0.49%; the actual proportion of our center was 4/2061, and as the size increased, the risk of incomplete resection sharply increased. In our opinion, the range of incomplete polyp resection ≤ 10 mm was acceptable.

Because the sample size was too small in this study, it is difficult to determine whether chronic renal failure was a risk factor for delayed bleeding. However, considering the report that chronic renal failure was the risk factor of immediate bleeding[16] and based on many endoscopists’ experience, this factor should be seriously considered.

There were several limitations to this study. In our center, we used standardized records for EMR to check each step of the procedure, complications, and management with endoscopic photos. However, it is possible that some information was incomplete or missed due to the characteristics of the retrospective design. Second, delayed bleeding with a long time interval could not be reported although the possibility of this occurring was extremely low[17]. Finally, this study did not provide strong evidence for safety in regards to delayed bleeding in a real outpatient setting. The results from this report were obtained from in-patient data. For more solid evidence, prospective study in a real out-patient setting environment should be performed.

In the present investigation, we observed that the risks of delayed bleeding and serious immediate bleeding were very low for a polyp ≤ 10 mm. Moreover, the risk of incomplete resection was acceptable, according to the outlined condition. From these findings, we conclude that it is safe and acceptable to perform outpatient-based EMR for polyps no more than 10 mm.

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) is widely performed in many clinical fields. Depending on the time of onset, cases of bleeding can be classified as either immediate or delayed. Delayed hemorrhages can be more serious because their onset is unpredictable and often occurs after hospital discharge. Although many endoscopists believe that it is safe to perform outpatient-based EMR for a polyp no more than 10 mm, no definite report about the possibility of delayed bleeding associated with specific conditions of alleged risk factors has been published.

Depending on the time of onset, cases of bleeding can be classified as either immediate or delayed. Cases of immediate bleeding directly following the procedure can be easily managed with recent advancing endoscopic technology and hemostasis equipment, but delayed hemorrhages can be more serious because their onset is unpredictable and often occurs after hospital discharge. The size of the polyp was determined to be the most reliable factor for delayed bleeding. However, there has been no definite report about the actual possibility of delayed bleeding according to the sizes of polyps.

In the present study, the authors revealed that the risks of delayed bleeding and serious immediate bleeding were very low for a polyp ≤ 10 mm. Moreover, the risk of incomplete resection was acceptable, according to the outlined condition.

If the size of the polyp is no more than 10 mm, it would be desirable to perform outpatient-based EMR. Unless, inpatient-based practice might be needed to ensure safety of a patient regarding delayed bleeding.

Delayed bleeding was defined by two conditions in this article. The first condition was when the patient experienced more than one episode of hematochezia at least one hour after EMR. The second condition was identifiable evidence of hemorrhage from an EMR site.

This study is to evaluate the possibility of delayed bleeding according to specific situations of risk factors to understand conditions in which outpatient-based can be performed. This is very important study.

| 1. | Kantsevoy SV, Adler DG, Conway JD, Diehl DL, Farraye FA, Kwon R, Mamula P, Rodriguez S, Shah RJ, Wong Kee Song LM. Endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:11-18. |

| 2. | Rex DK. Have we defined best colonoscopic polypectomy practice in the United States? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:674-677. |

| 3. | Waye JD, Lewis BS, Yessayan S. Colonoscopy: a prospective report of complications. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;15:347-351. |

| 4. | Binmoeller KF, Thonke F, Soehendra N. Endoscopic hemoclip treatment for gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 1993;25:167-170. |

| 5. | Parra-Blanco A, Kaminaga N, Kojima T, Endo Y, Uragami N, Okawa N, Hattori T, Takahashi H, Fujita R. Hemoclipping for postpolypectomy and postbiopsy colonic bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:37-41. |

| 6. | Hachisu T. A new detachable snare for hemostasis in the removal of large polyps or other elevated lesions. Surg Endosc. 1991;5:70-74. |

| 7. | Sorbi D, Norton I, Conio M, Balm R, Zinsmeister A, Gostout CJ. Postpolypectomy lower GI bleeding: descriptive analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:690-696. |

| 8. | Kim JH, Lee HJ, Ahn JW, Cheung DY, Kim JI, Park SH, Kim JK. Risk factors for delayed post-polypectomy hemorrhage: a case-control study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:645-649. |

| 9. | Watabe H, Yamaji Y, Okamoto M, Kondo S, Ohta M, Ikenoue T, Kato J, Togo G, Matsumura M, Yoshida H. Risk assessment for delayed hemorrhagic complication of colonic polypectomy: polyp-related factors and patient-related factors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:73-78. |

| 10. | Sawhney MS, Salfiti N, Nelson DB, Lederle FA, Bond JH. Risk factors for severe delayed postpolypectomy bleeding. Endoscopy. 2008;40:115-119. |

| 11. | Buddingh KT, Herngreen T, Haringsma J, van der Zwet WC, Vleggaar FP, Breumelhof R, Ter Borg F. Location in the right hemi-colon is an independent risk factor for delayed post-polypectomy hemorrhage: a multi-center case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1119-1124. |

| 12. | Schlemper RJ, Riddell RH, Kato Y, Borchard F, Cooper HS, Dawsey SM, Dixon MF, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Fléjou JF, Geboes K. The Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia. Gut. 2000;47:251-255. |

| 13. | Rosen L, Bub DS, Reed JF, Nastasee SA. Hemorrhage following colonoscopic polypectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:1126-1131. |

| 14. | Church JM. Experience in the endoscopic management of large colonic polyps. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:988-995. |

| 15. | Consolo P, Luigiano C, Strangio G, Scaffidi MG, Giacobbe G, Di Giuseppe G, Zirilli A, Familiari L. Efficacy, risk factors and complications of endoscopic polypectomy: ten year experience at a single center. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2364-2369. |

| 16. | Kim HS, Kim TI, Kim WH, Kim YH, Kim HJ, Yang SK, Myung SJ, Byeon JS, Lee MS, Chung IK. Risk factors for immediate postpolypectomy bleeding of the colon: a multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1333-1341. |

| 17. | Singaram C, Torbey CF, Jacoby RF. Delayed postpolypectomy bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:146-147. |

P- Reviewer: Ikematsu H, Sajid MS S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN