Published online Feb 16, 2026. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v18.i2.114400

Revised: November 9, 2025

Accepted: January 4, 2026

Published online: February 16, 2026

Processing time: 138 Days and 20.2 Hours

The clinical management of small gastric submucosal tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer is a non-negligible challenge. We have proposed a safe and simple method called precutting endoscopic band ligation (EBL).

To assess the long-term viability of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and precutting EBL and clarify precutting EBL’s safety and efficacy.

In this retrospective study, 94 patients with small gastric muscularis propria tumors underwent ESD or precutting EBL at a tertiary hospital. Patient demo

We reviewed 94 patients with gastric submucosal tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer (< 20 mm), including 48 treated by ESD and 46 by precutting EBL. No local recurrences were detected in either group during follow-up, and the median follow-up period was 48.60 months (interquartile range: 48.00-60.00) in the ESD group and 52.00 months (interquartile range: 36.00-84.00) in the precutting EBL group. However, precutting EBL was significantly superior in terms of operative time (46 minutes vs 17 minutes, P < 0.001) and the AE rate (11.47% vs 0%, P = 0.024).

Precutting EBL had a shorter operative time than ESD and was associated with no AEs. Future randomized controlled studies are required to confirm the feasibility of this approach.

Core Tip: This article compared endoscopic submucosal dissection and precutting endoscopic band ligation (EBL) for gastric submucosal tumors < 20 mm originating from the muscularis propria. Both techniques achieved excellent long-term tumor control without recurrence, but precutting EBL demonstrated significant advantages, including a shorter operative time and fewer adverse events. These findings suggest that precutting EBL is a safer, simpler, and more efficient alternative to endoscopic submucosal dissection, warranting further validation in prospective randomized controlled trials.

- Citation: Ou Y, Wang J, Liu MF, Yuan R, Min J, Li S, Deng L. Retrospective comparison of precutting endoscopic band ligation and endoscopic submucosal dissection for small gastric muscularis propria tumors. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2026; 18(2): 114400

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v18/i2/114400.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v18.i2.114400

Gastric submucosal tumors (SMTs) originating from the muscularis propria (MP) are predominantly gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). These lesions typically exhibit an endophytic or intraluminal growth pattern and appear as submucosal protrusions on endoscopy or imaging. Small GISTs (diameter < 2 cm), regardless of their anatomical location, are generally associated with a very low or low risk of malignancy. Therefore, conservative management is recommended by the European Society for Medical Oncology Guidelines[1]. In a study including 378 patients with small GISTs, metastasis was observed at diagnosis in 11.4% of cases[2]. Therefore, tumor size alone should not guide clinical decision-making. Although current recommendations tend to be conservative, including for the management of low-risk GISTs, active resection should be considered according to the patient’s wishes[3].

With the advancement of endoscopic techniques, surgical excision is no longer the sole standard treatment for SMTs originating from the MP layer (SMT-MPs). Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), and endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR) can remove SMT-MPs effectively. These techniques have been applied in clinical practice, but they must be performed by experienced and skilled endoscopists and are time-consuming. Meanwhile, resecting MP lesions via standard endoscopic electrosurgery is technically demanding and may cause serious adverse events (AEs) such as perforation or bleeding. In contrast with EMR, ESD achieves a larger tissue resection range and improves overall lesion resection[4]. A North American study demonstrated that ESD is safe, effective, and associated with a lower recurrence rate for the treatment of select gastrointestinal neoplasms[5]. A meta-analysis revealed that in patients treated using ESD in the MP layer, the overall complete resection rate was decreased (84.4% vs 91.4%) compared to that when using ESD for lesions originating from the submucosal layer. ESD is difficult to perform for GISTs originating from the MP and growing extraluminally[6].

To address this challenge, we proposed a novel endoscopic technique involving endoscopic band ligation (EBL) with precutting of the covering mucosa, termed precutting EBL[7]. In a previous single-arm study, short-term safety and efficacy were proved initially. Nevertheless, extended follow-up is necessary to thoroughly evaluate its efficacy. The hypothesis of this study was that novel endoscopic management can reduce the incidence of hazards; has effectiveness comparable to ESD in terms of tumor recurrence over long-term follow-up; and can markedly reduce the operative time. Therefore, in this long-term and retrospective study, we investigated the feasibility and safety of this method for small SMT-MPs compared with traditional ESD.

A minimum of 12 participants per group was estimated to be required to achieve sufficient statistical power (90%) to detect a significant difference in operative time between the two surgical methods. The sample size calculation was conducted using the pwr package (version 1.3-0; https://cran.r-project.org/package=pwr) in R (version 4.4.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; https://www.R-project.org) based on an effect size of 1.41, a significance level of 0.05, and the difference in mean operative times (38.3 minutes vs 16.6 minutes) reported in previous studies[7,8]. The effect size was derived from the reported mean difference of 21.7 minutes between the two techniques, together with the corresponding variability in operative times described in the same references. This yielded a large estimated effect (d = 1.41). Although the minimum sample size required to ensure adequate statistical power (90%) was calculated to be 12 participants per group, to enhance the robustness of the findings, the final study was expanded to include a total of 94 patients.

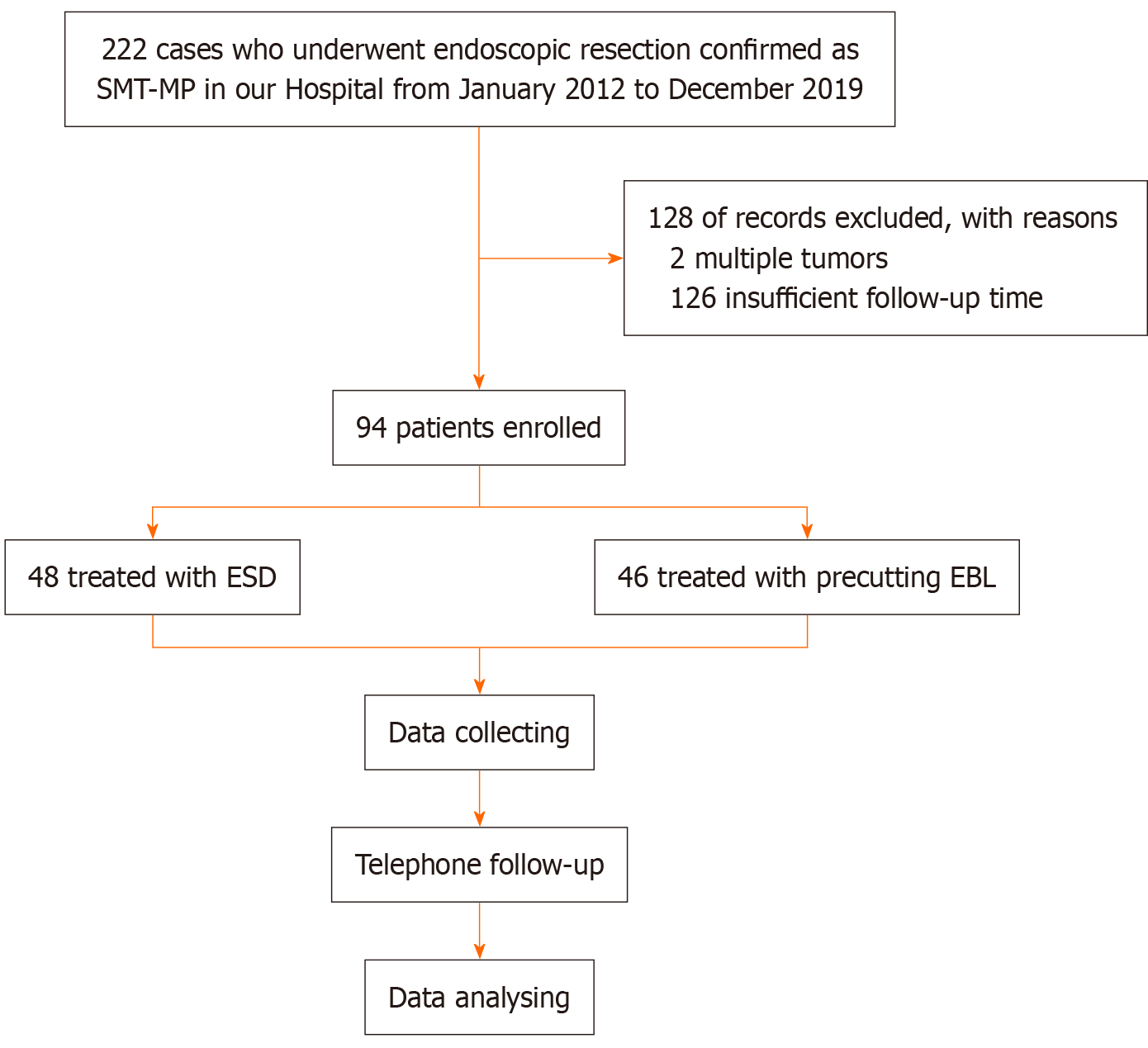

We retrospectively evaluated SMT-MP patients receiving ESD or precutting EBL at the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University between January 2012 and December 2019. Patients who satisfied all of the following criteria were considered eligible for the procedure: (1) Lesions < 20 mm; (2) Long-term (> 3 years) gastroscopic follow-up performed after surgery; and (3) Tumor originating from the MP layer. Those who met the following criteria were not included: (1) Non-compliance with endoscopic follow-up within 3 years; and (2) Multiple tumors. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2008). Due to its retrospective design, the requirement for informed consent was waived (Figure 1). It should be noted that the patients assigned to the precutting EBL group were identical to those described in our previous study, as they were part of the same patient cohort[7].

Before the procedure, endoscopic ultrasonography (EU-M2000, 20 MHz; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was generally per

For ESD, saline solution was injected to enable submucosal lifting. Then, using the Dual Knife (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and IT knife2 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), the mucosal tumor was closely incised and dissected.

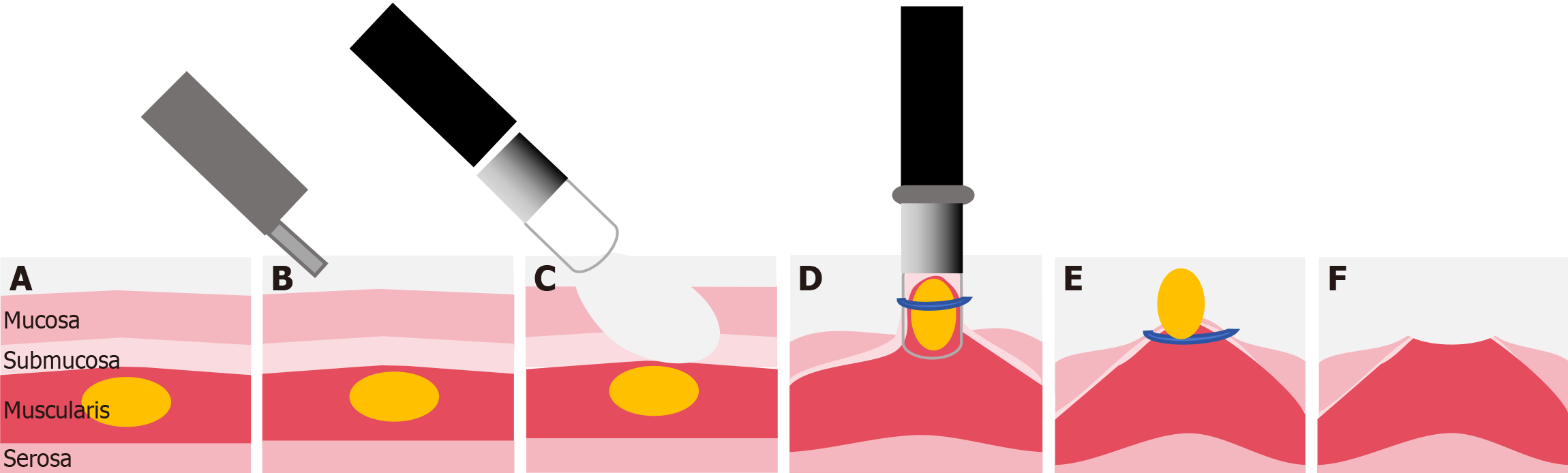

For precutting EBL, precutting was performed in the following sequence. To expose the SMT, the mucosa was denuded from the submucosal lesion using a standard endoscope (CV-260; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), electrosurgical loop snare (SD-210U-25; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and electronic cutting device (VIO 200S; ERBE, Tübingen, Germany)[7]. A standard endoscope equipped with an appropriate transparent ligation cap was employed to capture and ligate the lesion, avoiding electrocautery-assisted resection of the lesion or submucosal injection. In addition, we used three types of ligator caps for different tumor sizes; all ligators were disposable. Finally, given the small size of the mucosal defects, natural healing was sufficient, so prophylactic clipping to prevent bleeding or perforation was unnecessary[9]; the tumor was left to fall off due to necrosis, a process that takes about 2-7 days. Because no pathological results were obtained, the tumor cannot be evaluated for pathologic staging. A schematic of the precutting EBL process is shown in Figure 2.

All ESD patients were required to be hospitalized for observation after operation. AEs were evaluated using the Clavien-Dindo grading criteria[10]. The fasting time depended on tumor size and the occurrence of AEs. Most patients who underwent precutting EBL were managed as outpatients. They were instructed to fast for 6 hours after the procedure and were prescribed esomeprazole (40 mg once daily) for 2 weeks to minimize gastric mucosal injury. A subset of precutting EBL patients received inpatient care, either based on personal preference for closer postoperative monitoring or due to baseline comorbidities (e.g., urinary tract infection, coronary heart disease, or type 2 diabetes, with the latter requiring inpatient blood glucose monitoring). The remaining hospitalized patients received postoperative care similar to that provided after ESD. Postoperative management for hospitalized patients included nil per os for 24 hours and administration of proton pump inhibitors to protect the gastric mucosa. Antibiotics were administered selectively based on intraoperative findings, such as mucosal injury or prolonged procedure time.

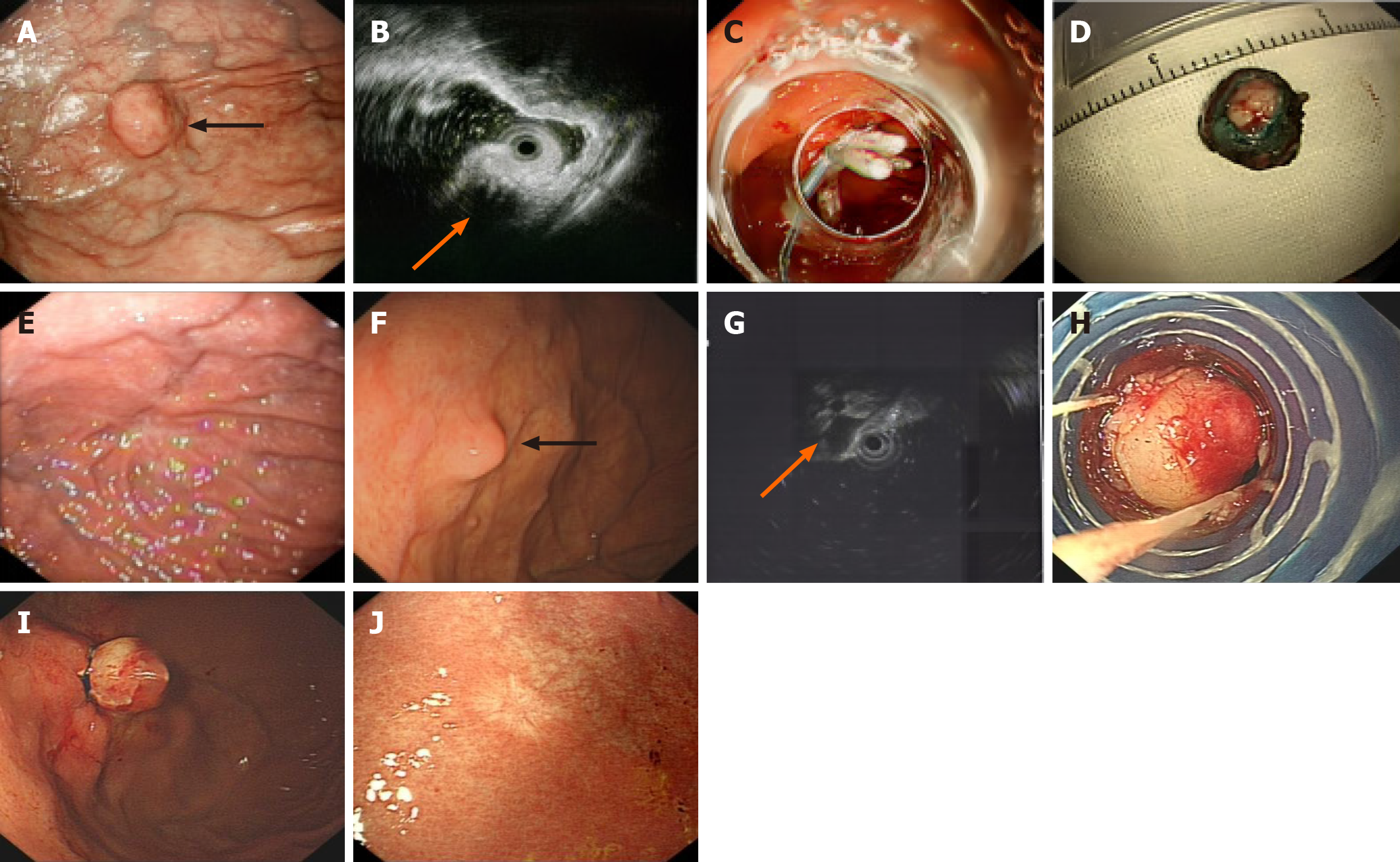

Postoperative tumor recurrence and the duration of the procedure were defined as the primary outcomes. To precisely assess the incidence of AEs, all patients received follow-up via telephone or outpatient visit 1 month postoperatively during the research phase. Telephone follow-up was conducted by trained researchers primarily for patients unable to attend on-site visits (e.g., due to geographic distance) and documented in structured telephone follow-up forms (with fields for “patient-reported symptoms”, “adverse events”, and “follow-up compliance”). Long-term follow-up remains the only reliable approach to determine whether a resected lesion has progressed or recurred. Postoperative endoscopic surveillance was conducted in accordance with the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Guidelines for ESD[11,12]. The follow-up protocol included an endoscopic examination at 3-6 months after the procedure, followed by annual endoscopic surveillance thereafter. For patients with tumors initially presenting high-risk features (e.g., a specific location or growth pattern), we supplemented annual abdominal ultrasound (or contrast-enhanced computed tomography if clinically indicated) to screen for distant metastasis. If no recurrence was detected in subsequent follow-ups, the surveillance interval could be extended as appropriate. Endoscopic follow-up entailed detailed inspection of the presence of clips and the scar in the resection area. Data were also collected for patients who received endoscopic follow-up in other hospitals. Beyond standardized follow-up, the clinical care workflow and safety safeguards were fully unified for both groups. All follow-up plans were formulated by the same medical team, and both cohorts adhered to the identical “abnormal finding management protocol”. To ensure data accuracy, all follow-up records (electronic endoscopic reports and telephone forms) were cross-checked by two independent researchers every 6 months during the study period; discrepancies (e.g., missing endoscopic data) were resolved by reviewing original procedure notes or contacting attending clinicians. The procedure and postoperative surveillance steps are described in Figure 3.

We collected data on age, gender, tumor size, tumor location and histopathology, patient type, procedure duration, local recurrence, AEs, follow-up time, and cost of operation. Surgical costs mainly refer to surgical consumables. The source of data was our hospital electronic medical record system. Endoscopic findings (e.g., lesion size, recurrence status) were documented by attending endoscopists immediately after each procedure, with standardized templates used to ensure consistency.

R version 4.4.3 was employed for data analysis. The χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze categorical variables, while the Shapiro-Wilk test assessed data distribution normality. Age, which was normally distributed, was expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed using a t-test. Continuous variables with skewed distributions were summarized as median [interquartile range (IQR)] and analyzed between groups using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were described as n (%). P < 0.05 (two-sided) indicated statistical significance. Inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) was used to balance baseline characteristics, including age, gender, location, and size, between the two study groups (ESD and precutting EBL). Covariate balance was evaluated using standardized mean differences (SMDs), with values < 0.1 indicating adequate balance between groups. Univariate linear regression analyses were first performed to identify potential predictors of the outcome variable. Variables with a P value < 0.05 were considered candidates for multivariate analysis. Multicollinearity among covariates was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF), and variables with significant collinearity were considered for exclusion. A multivariate linear regression model was then constructed using stepwise selection based on the Akaike information criterion, using both the forward and backward directions. To evaluate model robustness, results before and after IPTW adjustment were compared. The statistical methods were reviewed by the Biostatistics Teaching and Research Section, Fourth Military Medical University.

From January 2012 to December 2019, 94 patients with SMT-MPs were finally included. The baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The research process is presented as a simple flow chart in Figure 1. Patients were separated into ESD and precutting EBL groups. In the ESD group, the mean age at baseline was 54.27 ± 8.61 years, with 56.25% of patients being female and 62.50% having tumors located in the gastric fundus. The median tumor size was 10 mm (IQR: 10.00-10.00). In comparison, the precutting EBL group had a mean age of 53.13 ± 11.10 years at baseline; 56.52% were female patients, and 58.70% of tumors were situated in the fundus. The median tumor diameter was 11 mm (IQR: 9.25-14.75). No significant differences in gender, age, tumor size, and tumor location were detected between the groups. Notably, prior to IPTW adjustment, tumor size, and age exhibited SMDs > 0.1, suggesting meaningful baseline im

| Variables | ESD (n = 48) | Precutting EBL (n = 46) | P value | Standardized difference | ||

| Before IPTW | After IPTW | Before IPTW | After IPTW | |||

| Gender | - | - | 1 | 0.964 | 0.005 | 0.010 |

| Male | 21 (43.75) | 20 (43.48) | - | - | - | - |

| Female | 27 (56.25) | 26 (56.52) | - | - | - | - |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 54.27 ± 8.61 | 53.13 ± 11.10 | 0.578 | 0.734 | 0.115 | 0.013 |

| Tumor size, mm | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 10.00 (10.00-10.00) | 11.00 (9.25-14.75) | 0.134 | 0.939 | 0.333 | 0.016 |

| Tumor location | - | - | 0.868 | 0.977 | 0.078 | 0.006 |

| Fundus | 30 (62.50) | 27 (58.70) | - | - | - | - |

| Others | 18 (37.50) | 19 (41.30) | - | - | - | - |

| Cardia | 1 (2.08) | 1 (2.17) | - | - | - | - |

| Body | 15 (31.25) | 9 (19.57) | - | - | - | - |

| Antrum | 2 (4.17) | 9 (19.57) | - | - | - | - |

Table 2 shows the perioperative outcomes. The main AEs for ESD were infection (3/48, 6.25%), hypotension (1/48, 2.08%) and antispasmodic-induced dysuria (1/48, 2.08%). No obvious AEs were observed in the remaining 46 precutting EBL patients. Five patients experienced grade II complications, all of which required pharmacological treatment such as antibiotics. No patient required surgical, endoscopic, or radiological intervention. These events were considered mo

| Variables | Before IPTW adjustment | After IPTW adjustment | ||||

| ESD (n = 48) | Precutting EBL (n = 46) | Significance (P value) | ESD (n = 93.97) | Precutting EBL (n = 94.27) | Significance (P value) | |

| Procedure duration, minutes | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 46 (40-50) | 17 (16-18) | < 0.001 | 46.00 (40.00-49.56) | 17.00 (16.00-18.00) | < 0.001 |

| Adverse events | 5 (10.42) | 0 | 0.073 | 10.78 (11.47) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.024 |

| Cost of operation | ||||||

| Median (IQR), dollars | 1754.48 (1585.08-1843.45) | 525.33 (507.59-657.71) | < 0.001 | 1751.72 (1557.30-1852.06) | 515.57 (507.59-627.14) | < 0.001 |

| Patient type | - | - | < 0.001 | - | - | < 0.001 |

| Outpatient | 0 (0.00) | 15 (32.61) | - | 0.00 (0.00) | 29.09 (30.86) | - |

| Inpatient | 48 (100.00) | 31 (67.39) | - | 93.97 (100.00) | 65.18 (69.14) | - |

| Follow-up time, months | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 48 (48-60) | 54 (36-84) | 0.394 | 48.60 (48.00-60.00) | 52.00 (36.00-84.00) | 0.398 |

| Local recurrence | - | - | NA | - | - | NA |

| No recurrence | 48 (100.00) | 46 (100.00) | - | 93.97 (100.00) | 94.27 (100.00) | - |

| Recurrence | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

In an adjusted analysis, the median follow-up time for ESD and precutting EBL was 48.60 months (IQR: 48.00-60.00) and 52.00 months (IQR: 36.00-84.00), respectively. The follow-up duration did not differ significantly between the two groups (P = 0.398). Notably, no local recurrence occurred in either group, and no patients died during follow-up.

Because the lesion wounds sloughed off spontaneously after ligation in the precutting group, no pathological results were obtained. In the ESD group, we classified patients based on histopathological and immunohistochemical staining. Histopathological assessment revealed 48/48 R0 resections (100%), of which 33/48 were GISTs. The mitotic index was < 5/50 high-power fields in all cases. The distribution of lesion types is shown in the Supplementary Table 1.

To explore factors associated with surgical time, we first conducted univariable linear regression analyses for each candidate covariate. Variables with P values < 0.2 in the univariable analysis, including method, follow-up time, size, cost, inpatients, and AEs, were included in the multivariable model. Before constructing the multivariable model, multicollinearity was assessed using the VIF. All included variables showed acceptable VIF values (< 10), with method (VIF = 8.34) and cost (VIF = 7.84) exhibiting multicollinearity that was moderate but still within acceptable thresholds. Stepwise linear regression analysis (Akaike information criterion-based selection) was then performed to identify independent predictors of surgical time. The final model retained method, cost, and AEs as covariates. The overall model demonstrated excellent explanatory power [R2 = 0.899, adjusted R2 = 0.896, F (3, 90) = 267.0, P < 0.001]. Notably, surgical method was a strong predictor of surgical time (β = -24.55, 95% confidence interval: -30.10 to -19.00, P < 0.001), indicating that patients treated with the novel method had shorter operative durations compared to those in the conventional group. Neither cost (β = 0.0037, P = 0.115) nor AEs (β = -3.46, P = 0.135) showed statistical significance, although their inclusion improved the model’s overall fit.

As presented in Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 3, the coefficient for surgical method remained significant in both the unweighted and IPTW-weighted models. The estimated coefficient for method remained significant, and was even more pronounced in the IPTW-weighted model (β = -28.31) compared to the unweighted model (β = -24.55), suggesting a robust reduction in procedure time in association with the experimental method. The estimates for cost and AEs in the unweighted model were not statistically significant, and were not included in the weighted model due to the IPTW adjustment focusing solely on method-related confounding.

Small gastric stromal tumors, a common subtype of SMT-MPs, possess malignant potential, even when measuring < 2 cm. These lesions may also exhibit significant growth during follow-up. As SMT-MPs primarily arise from the MP[13], their complete removal remains technically challenging. Currently, simple and effective techniques for the complete removal of small gastric tumors arising from the MP are limited. Endoscopic resection has been shown to be more effective than surgery for treating SMT-MPs. Endoscopic resection is associated with rapid recovery, minimal invasion, and cost-effectiveness. ESD, EMR, and EFTR are generally acknowledged as the most recognized techniques[3]. In developing regions, the utilization of these techniques is limited by high cost and the requirement for sophisticated skills in experienced endoscopists. A review pointed out that the median procedure time for ESD was 46.5-70.16 minutes, and that for EFTR was 41-271 minutes[13]. Hence, there is an increasing need for novel endoscopic treatments with easier procedures and lower cost. Our previous retrospective investigation, which involved 111 patients and 124 gastric SMT-MPs, revealed that the precutting EBL approach is a practical and efficient option for resecting gastric lesions smaller than 16 mm[7].

The key procedure of precutting EBL is the additional precutting. Precutting uncovers tumors in MP layers and ensures ligation of the whole tumor body. Moreover, closure of the muscle defect is common in ESD, which is larger in the final defect compared to precutting EBL. In contrast, precutting EBL results in small wounds in which defect closure is not routinely performed, based on our hands-on experience. Installation of an appropriate ligator on the endoscope could avoid excess suction and ligation. Concurrent en bloc resection does not increase the risk of procedure-related complications[14]. In addition, lesions located in the anterior wall of the gastric fundus and gastric fundus fornix are exposed more efficiently in our experience of precutting EBL.

Our study found that ESD and precutting EBL are similarly effective in the treatment of SMT-MPs. However, precutting EBL has a shorter surgery time and fewer AEs. Some studies have pointed out that prolonged operation time increases the incidence of post-ESD hemorrhage[15,16]. Precutting EBL consists of only two steps, precutting and ligating, for a relatively short operation time.

Furthermore, several studies demonstrated that ESD has a higher incidence of postoperative complications[17,18]. AEs associated with ESD include perforation of the gastric wall and massive bleeding. When perforation occurs, there is a risk of bacterial contamination in the peritoneum.

For the SMT-MPs in this study, AEs tended to be more common with ESD, with precutting EBL not causing any com

During the median observational period for ESD and precutting EBL, patients underwent more than one endoscopic follow-up to evaluate wound healing and tumor recurrence. At the last follow-up, no patients had recurrence or apparent discomfort during food intake, and there were no differences in long-term survival between the groups.

There are some limitations to our study. First, it was limited by its retrospective nature, and a prospective randomized controlled trial is required to supplement the findings. For instance, patients with SMT-MPs from multiple centers could be enrolled and randomly assigned to ESD and precutting EBL groups. By comparing the metastasis rate and treatment efficacy between the two groups over a long follow-up period, this design would provide a higher level of evidence re

While we pioneered the use of precutting EBL to treat SMT-MPs, our study was conducted at a single medical center without randomization. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the long-term outcomes of precutting EBL and ESD. Given the feasibility of precutting EBL in SMT-MPs, future studies should aim to further validate the efficacy and safety of precutting EBL.

The results indicate that both ESD and precutting EBL can effectively treat small gastric SMT-MPs. However, precutting EBL had a shorter operation time and fewer AEs. Precutting EBL has potential as a widely used treatment, especially for lesions originating from the MP layer. In conclusion, precutting EBL is feasible and safe for treating small gastric SMT-MPs.

| 1. | ESMO/European Sarcoma Network Working Group. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2014;25 Suppl 3:iii21-iii26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Coe TM, Fero KE, Fanta PT, Mallory RJ, Tang CM, Murphy JD, Sicklick JK. Population-Based Epidemiology and Mortality of Small Malignant Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors in the USA. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:1132-1140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cheng BQ, Du C, Li HK, Chai NL, Linghu EQ. Endoscopic resection of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Dig Dis. 2024;25:550-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Oka S, Tanaka S, Kaneko I, Mouri R, Hirata M, Kawamura T, Yoshihara M, Chayama K. Advantage of endoscopic submucosal dissection compared with EMR for early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:877-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 487] [Cited by in RCA: 535] [Article Influence: 26.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Draganov PV, Aihara H, Karasik MS, Ngamruengphong S, Aadam AA, Othman MO, Sharma N, Grimm IS, Rostom A, Elmunzer BJ, Jawaid SA, Westerveld D, Perbtani YB, Hoffman BJ, Schlachterman A, Siegel A, Coman RM, Wang AY, Yang D. Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection in North America: A Large Prospective Multicenter Study. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:2317-2327.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Bang CS, Baik GH, Shin IS, Suk KT, Yoon JH, Kim DJ. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric subepithelial tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Korean J Intern Med. 2016;31:860-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Li S, Liang X, Zhang B, Tao X, Deng L. Novel endoscopic management for small gastric submucosal tumors: A single-center experience (with video). Dig Liver Dis. 2021;53:895-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li B, Chen T, Qi ZP, Yao LQ, Xu MD, Shi Q, Cai SL, Sun D, Zhou PH, Zhong YS. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic resection for small submucosal tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer in the gastric fundus. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:2553-2561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Libânio D, Pimentel-Nunes P, Bastiaansen B, Bisschops R, Bourke MJ, Deprez PH, Esposito G, Lemmers A, Leclercq P, Maselli R, Messmann H, Pech O, Pioche M, Vieth M, Weusten BLAM, Fuccio L, Bhandari P, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection techniques and technology: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Technical Review. Endoscopy. 2023;55:361-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 42.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, de Santibañes E, Pekolj J, Slankamenac K, Bassi C, Graf R, Vonlanthen R, Padbury R, Cameron JL, Makuuchi M. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250:187-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6210] [Cited by in RCA: 9215] [Article Influence: 542.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Pimentel-Nunes P, Libânio D, Bastiaansen BAJ, Bhandari P, Bisschops R, Bourke MJ, Esposito G, Lemmers A, Maselli R, Messmann H, Pech O, Pioche M, Vieth M, Weusten BLAM, van Hooft JE, Deprez PH, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial gastrointestinal lesions: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2022. Endoscopy. 2022;54:591-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 579] [Cited by in RCA: 479] [Article Influence: 119.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Deprez PH, Moons LMG, OʼToole D, Gincul R, Seicean A, Pimentel-Nunes P, Fernández-Esparrach G, Polkowski M, Vieth M, Borbath I, Moreels TG, Nieveen van Dijkum E, Blay JY, van Hooft JE. Endoscopic management of subepithelial lesions including neuroendocrine neoplasms: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2022;54:412-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 60.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Tan Y, Tan L, Lu J, Huo J, Liu D. Endoscopic resection of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Imai K, Hotta K, Yamaguchi Y, Ito S, Ono H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for large colorectal neoplasms. Dig Endosc. 2017;29 Suppl 2:53-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yano T, Tanabe S, Ishido K, Suzuki M, Kawanishi N, Yamane S, Watanabe A, Wada T, Azuma M, Katada C, Koizumi W. Different clinical characteristics associated with acute bleeding and delayed bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection in patients with early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:4542-4550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Toyokawa T, Inaba T, Omote S, Okamoto A, Miyasaka R, Watanabe K, Izumikawa K, Horii J, Fujita I, Ishikawa S, Morikawa T, Murakami T, Tomoda J. Risk factors for perforation and delayed bleeding associated with endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric neoplasms: analysis of 1123 lesions. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:907-912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhao Y, Wang C. Long-Term Clinical Efficacy and Perioperative Safety of Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection versus Endoscopic Mucosal Resection for Early Gastric Cancer: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:3152346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Facciorusso A, Antonino M, Di Maso M, Muscatiello N. Endoscopic submucosal dissection vs endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer: A meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;6:555-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 19. | Libânio D, Costa MN, Pimentel-Nunes P, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Risk factors for bleeding after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:572-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lin C, Sui C, Tao T, Guan W, Zhang H, Tao L, Wang M, Wang F. Prognostic analysis of 2-5 cm diameter gastric stromal tumors with exogenous or endogenous growth. World J Surg Oncol. 2023;21:139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhang H, Liu Q. Prognostic Indicators for Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors: A Review. Transl Oncol. 2020;13:100812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/