Published online Feb 16, 2026. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v18.i2.113912

Revised: October 17, 2025

Accepted: December 12, 2025

Published online: February 16, 2026

Processing time: 151 Days and 8.7 Hours

Artificial intelligence (AI) has become an increasingly valuable tool in gastro

Core Tip: This article highlights the evolving role of artificial intelligence in gastrointestinal endoscopy for patients with inflammatory bowel disease, emphasizing its potential to improve early dysplasia detection and strengthen colorectal cancer surveillance. Artificial intelligence-assisted systems enhance diagnostic accuracy, reduce interobserver variability, and support real-time clinical decision-making in the management of inflammatory bowel disease.

- Citation: Popovic DD, Dragovic M, Panic N, Marjanovic-Haljilji M, Glisic T, Lukic S, Mijac D, Bogdanovic J, Bogdanović L, Djokovic A, Starcevic A, Filipovic B. Harnessing artificial intelligence in gastrointestinal endoscopy for early detection of dysplastic lesions in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2026; 18(2): 113912

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v18/i2/113912.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v18.i2.113912

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are chronic, progressive, immune-mediated disorders that affect the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and extraintestinal organs. The main clinical types are ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease, while some patients are classified as having indeterminate colitis or IBD unclassified. Although the exact cause is not fully under

Human intelligence refers to the cognitive capacity to learn, adapt, and understand abstract concepts, including emotional and social dimensions[3]. Importantly, it involves the ability to apply prior knowledge and learned patterns to predict outcomes in novel situations. Artificial intelligence (AI) replicates many of these functions synthetically.

In endoscopy, AI tools are mainly computer-aided detection (CADe) systems, which identify abnormalities with high sensitivity, and computer-aided diagnosis systems, which characterize lesions with high specificity[4,5]. AI includes machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), with ML often classified into supervised, unsupervised, and re

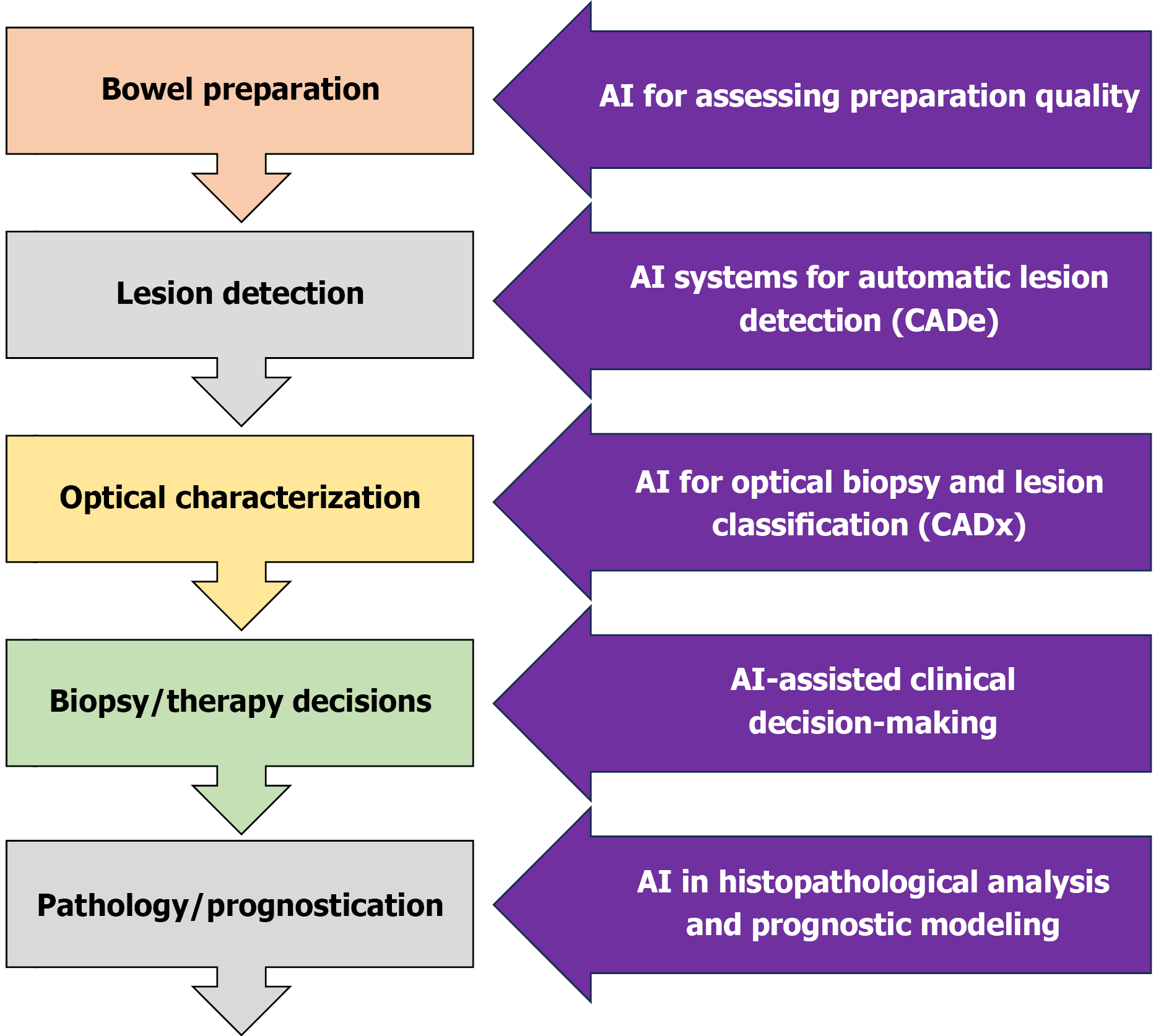

The integration of AI into medicine is advancing rapidly, particularly in imaging-focused fields such as radiology and gastroenterology. In IBD endoscopy, AI development focuses on early detection of premalignant lesions, reduction of human error, and improved assessment of inflammatory activity. Accurate evaluation currently requires expertise and is affected by significant interobserver variability[1]. Key applications of AI in IBD include dysplasia detection, colorectal cancer (CRC) screening, and standardized assessment of disease activity. While several reviews have explored the application of AI in gastroenterology, this review specifically focuses on the challenges and recent advancements in detecting dysplasia in patients with IBD. Unlike previous works that broadly address AI applications in IBD or general endoscopy, our analysis emphasizes the unique clinical, technological, and pathological aspects related to dysplasia surveillance in the context of IBD. A schematic overview of the endoscopic approach to IBD and potential AI integration points throughout the workflow is provided in Figure 1.

This narrative review explores the application of AI in GI endoscopy for detecting dysplastic lesions in patients with IBD. The focus is on both real-time and offline AI-based solutions, emphasizing their clinical relevance, diagnostic accuracy, and potential integration into routine surveillance practices.

A comprehensive literature search was performed in PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science databases to identify relevant studies published from January 2015 to June 2025. The search strategy combined AI-related keywords (“artificial intelligence”, “machine learning”, “deep learning”) with IBD-specific terms (“inflammatory bowel disease”, “ulcerative colitis”, “Crohn’s disease”) and endoscopy-related terms (“dysplasia”, “neoplasia”, “endoscopy”, “colonoscopy”). Studies were included if they investigated AI-based detection or classification of dysplastic or neoplastic lesions in IBD populations using endoscopic imaging modalities such as high-definition white-light endoscopy (HD-WLE), chromoendoscopy, confocal laser endomicroscopy (CLE), or endocytoscopy. Both real-time and offline AI applications in clinical or experimental settings were considered. Non-English articles, studies not focusing on IBD-related dysplasia, research limited to histopathology or genomics without endoscopic correlation, and non-original publications (except those influencing surveillance guidelines) were excluded.

Given the narrative nature of this article, no formal risk-of-bias assessment nor systematic data extraction was per

One of the key aspects of endoscopic evaluation in patients with IBD is the timely detection of dysplasia, which enables prompt and adequate therapeutic intervention. The relevance of AI in dysplasia detection has been confirmed by several significant studies.

One of the most impactful AI-based models for detecting both polypoid and non-polypoid lesions in patients with IBD was developed by Guerrero Vinsard et al[12] in 2023. This model was trained using data from 3437 colonoscopies performed with both HD-WLE and dye-based chromoendoscopy[12]. Key inclusion criteria were the presence of a macroscopically visible lesion during surveillance colonoscopy in patients with IBD, and histopathological confirmation of the findings[12]. Lesions were categorized into five groups, namely dysplastic lesions, non-dysplastic lesions, pseudopolyps, superficial elevated components (SECs), and sessile serrated adenomas (SSAs)[12].

The CADe system demonstrated excellent diagnostic performance, achieving a sensitivity of 95.1%, specificity of 98.8%, positive predictive value (PPV) of 98.9%, negative predictive value (NPV) of 94.7%, overall accuracy of 96.8%, and an area under the curve of 0.85[12]. The algorithm achieved a similar sensitivity of 90% for both non-dysplastic and dysplastic polyps, with a PPV of 100% for non-dysplastic polyps and 95% for dysplastic polyps[12]. For SECs, the system achieved a sensitivity of 85% and a PPV of 100%, while for SSAs, sensitivity reached 94% with a PPV of 100%[12]. In terms of lesion size, the IBD-CADe system showed consistent performance for smaller lesions, with a true positive rate of 91%-93%, whereas detection accuracy slightly declined for lesions larger than 10 mm, with a true positive rate of 85%[12]. These results reflect the model’s diagnostic performance using HD-WLE.

In contrast, the system’s performance when applied to chromoendoscopy images was notably lower, with a sensitivity of 67.4%, specificity of 88.0%, PPV of 83.3%, accuracy of 77.8%, and an area under the curve of 0.65[12]. The highest sensitivity in this modality was noted for SECs, while detection of SSAs was markedly reduced, with a true positive rate of only 36%[12]. Detection rates for dysplastic, non-dysplastic lesions, and pseudopolyps were relatively comparable. For chromoendoscopy, the highest true positive rate of 73% was recorded for lesions larger than 10 mm[12].

Another AI system developed by Yamamoto et al[13] employed a deep CNN architecture based on EfficientNet-B3 to differentiate neoplastic lesions in patients with IBD. Lesions were classified into two groups: Adenocarcinoma/high-grade dysplasia and low-grade dysplasia/sporadic adenoma/normal mucosa[13]. The AI model demonstrated a superior diagnostic accuracy of 79% [95% confidence interval (CI): 72.5%-84.6%], outperforming non-expert endoscopists, who achieved an accuracy of 75.8% (95%CI: 72.0%-79.3%), and slightly exceeding the accuracy of expert endoscopists at 77.8% (95%CI: 74.7%-80.8%)[13]. The model’s sensitivity and specificity were 72.5% (95%CI: 60.4%-82.5%) and 82.9% (95%CI: 74.8%-89.2%), respectively, suggesting its applicability in routine clinical practice for objective assessment of high-risk lesions in patients with IBD[13].

Early detection of dysplasia is inextricably linked to the implementation of regular screening and surveillance colonoscopies in patients with IBD. Dysplasia is rarely identified during the initial colonoscopy at diagnosis, as its development requires a prolonged period of chronic inflammation and disease progression.

Certain subgroups of patients with IBD are at increased risk of developing CRC compared to the general population[14,15]. Owing to the adoption of modern, innovative detection tools and advanced therapeutic modalities, the incidence and mortality of IBD-associated CRC have significantly decreased in recent years[15].

Chronic inflammation is the key driver of neoplastic transformation in IBD. The cumulative effect of prolonged inflammation promotes the development of dysplastic lesions - characterized by dysplastic cells extending throughout the crypt height in colitis - which may serve as precursors to colitis-associated CRC[15]. Histologically, dysplasia is defined as a neoplastic proliferation of the intestinal mucosa confined to the basement membrane, without evidence of invasion[16].

The Paris classification is commonly used to describe the morphology of superficial GI lesions in IBD[17]. According to this system, GI lesions are categorized into polypoid and non-polypoid types. Polypoid lesions may be pedunculated, semi-pedunculated, or sessile, while non-polypoid lesions include slightly elevated, flat, slightly depressed, or ulcerated/eroded morphologies[17].

Despite significant advances in endoscopic technology and lesion detection techniques, a considerable proportion of adenomas - especially those with malignant potential - remain undetected. A meta-analysis by Zhao et al[18], based on more than 15000 tandem colonoscopies, reported miss rates of 26% (95%CI: 23%-30%) for adenomas, 9% (95%CI: 4%-16%) for advanced adenomas, and 27% (95%CI: 16%-40%) for serrated polyps. As human error is the primary contributor to these missed lesions, there is growing interest in AI-assisted detection tools to support early CRC diagnosis. However, it is important to note that inadequate bowel preparation - a factor beyond the current scope of AI correction - continues to pose a significant challenge to optimal visualization and lesion detection.

Various AI-based systems have been developed for the early detection of colorectal lesions using DL and ML models[18]. Most studies show that AI systems significantly improve the adenoma detection rate compared to human en

One of the most effective techniques for dysplasia detection remains chromoendoscopy, which can be performed using either dye-based chromoendoscopy or virtual chromoendoscopy (VCE)[21]. Dye-based chromoendoscopy involves the topical application of contrast agents such as indigo carmine or absorptive dyes such as methylene blue or crystal violet directly onto the mucosa to enhance visualization of subtle abnormalities. Each dye has its advantages; indigo carmine and crystal violet can be easily applied using a spray catheter, whereas methylene blue requires additional preparation. Contrast dyes are more commonly used in the colon, while absorptive dyes are typically reserved for the upper GI tract[22,23]. In contrast, VCE employs optical or digital technologies to achieve mucosal contrast enhancement without the need for dyes. Optical filter-based systems, such as narrow band imaging (NBI), restrict the light spectrum to narrow blue and green wavelengths absorbed by hemoglobin, thereby enhancing vascular patterns and mucosal detail. Digital post-processing systems, including i-SCAN and Fujifilm’s VCE system, further refine image contrast through algorithmic enhancement[21,23,24].

HD-WLE provides image resolutions of up to two million pixels per frame, facilitating detailed assessment of mucosal architecture[25]. For even greater optical precision, methods such as CLE and endocytoscopy allow for real-time, high-magnification imaging. These methods - often termed “optical biopsy” tools - enable targeted lesion evaluation using fluorescent dyes and enhanced magnification[26]. CLE systems are available in two configurations: Probe-based CLE and endoscope-based CLE. Although CLE is widely used in GI endoscopy, it is particularly helpful in assessing dysplasia, inflammation, and disease activity in patients with IBD[26]. In a study by Kiesslich et al[27], the performance of CLE and chromoendoscopy was compared with that of conventional colonoscopy. The detection rate of neoplastic lesions in patients with UC was nearly five times higher when advanced imaging techniques were used compared to conventional colonoscopy alone[27]. Various guidelines exist for endoscopic surveillance of patients with IBD, and the most commonly used are those from the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization (ECCO)[28]. According to these recommendations, the risk of CRC is highest in patients with extensive colitis, moderate in those with left-sided (segmental) colitis, and lowest in those with proctitis[28]. Patients with severe inflammation, colitis associated with primary sclerosing cho

The SCENIC consensus also provides recommendations for surveillance endoscopy in patients with IBD and highlights the superiority of chromoendoscopy over WLE. According to these guidelines, chromoendoscopy is preferred to WLE, particularly when standard-definition colonoscopy is used[29].

Although current guidelines provide clear recommendations for surveillance colonoscopies in patients with IBD, they still do not include instructions for the use of AI-assisted detection systems - an area expected to evolve and become more standardized in the near future.

The first AI system for computer-aided polyp detection approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration was GI Genius (Medtronic Corp., Dublin, Ireland)[30]. Since then, several AI-based systems, such as GI Genius, Endo-AID (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), CAD EYE (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan), Discovery (Pentax Medical, Tokyo, Japan), and EndoBRAIN (Cybernet Systems Corp., Ann Arbor, MI, United States) have been introduced into clinical practice. Among these, EndoBRAIN has been specifically tested in patients with IBD.

In a multicenter study conducted by Kudo et al[31], the EndoBRAIN system was evaluated for its diagnostic per

Neoplasia detection in patients with IBD remains a significant diagnostic challenge, as inflammatory and regenerative mucosal changes can obscure the presence of dysplasia. To improve the detection and characterization of such lesions, Abdelrahim et al[32] developed a deep artificial neural network model based on the RetinaNet architecture with a ResNet-101 backbone. This design enables precise extraction and analysis of complex image features during endoscopic assessment. In the initial phase of model development, the system was evaluated using a dataset of 478 static endoscopic images obtained from 30 patients with IBD. Among these, 25 neoplastic lesions, including sessile serrated polyps, were identified in 10 patients. The model demonstrated a sensitivity of 93.5% and specificity of 80.6% for lesion detection[32]. In the second, real-time validation phase during colonoscopy in an additional 30 patients with IBD, 25 neoplastic lesions were detected in 11 patients. The system achieved a lesion detection rate of 90.4%, with an average of 4.6 lesions and 0.96 neoplasms per colonoscopy[32]. For lesion characterization (neoplastic vs non-neoplastic), the model showed 87.5% sensitivity and 80.6% specificity[32].

These findings are particularly encouraging given the diagnostic complexity posed by chronic inflammatory conditions such as IBD. The ability to apply AI in real time opens promising avenues for more consistent, objective, and reproducible surveillance strategies - especially in centers with limited access to highly experienced endoscopists.

In addition to large-scale studies, several case reports have highlighted the potential impact of AI in dysplasia detection.

Maeda et al[33] described the case of a 72-year-old patient with an 18-year history of ulcerative pancolitis who underwent screening colonoscopy using HD-WLE assisted by the EndoBRAIN-EYE AI detection system. This system successfully identified two dysplastic lesions, which were subsequently confirmed by histopathological examination.

Similarly, Fukunaga et al[34] reported the case of a 46-year-old woman with long-standing pancolitis in whom a suspicious rectal lesion was detected during surveillance endoscopy using NBI and endocytoscopy. The EndoBRAIN system classified the lesion as neoplastic, which was later confirmed as high-grade dysplasia on histological examination. The patient underwent endoscopic submucosal dissection as definitive treatment[34].

Both reports emphasized that AI-assisted systems may improve the early detection of neoplastic changes, especially when procedures are performed by non-expert endoscopists[33,34]. Moreover, they highlighted the potential of AI to reduce the number of unnecessary biopsies in patients with long-standing UC, thereby increasing procedural efficiency and reducing patient discomfort. The key characteristics of all studies discussed in this review, including study design, dataset, and AI performance, are summarized in Table 1.

| Ref. | Country | AI model/technique | Study design | Dataset | AI performance | |||

| Mode | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) | |||||

| Guerrero Vinsard et al[12], 2023 | United States | IBD-CADe system with HD-WLE and chromoendoscopy (Scaled-YOLOv4) | Retrospective | 3437 colonoscopies, 1692 endoscopic images (HD-WLE and dye chromoendoscopy) | HD-WLE | 95.1 | 98.8 | 96.8 |

| Chromoendoscopy | 67.4 | 88 | 77.8 | |||||

| Yamamoto et al[13], 2022 | Japan | Deep CNN (EfficientNet-B3) | Retrospective (Pilot Study) | 862 endoscopic images (WLE and chromoendoscopy) | - | 72.5 | 82.9 | 79 |

| Abdelrahim et al[32], 2024 | United Kingdom | Deep CNN (RetinaNet; ResNet-101 backbone) | Prospective | 478 endoscopic images and real-time colonoscopy data | Lesion detection | 93.5 | 80.6 | N/A |

| Lesion characterization | 87.5 | 80.6 | N/A | |||||

| Maeda et al[33], 2021 | Japan | EndoBRAIN-EYE | Case report | Single case (patient with ulcerative colitis) | - | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Fukunaga et al[34], 2021 | Japan | EndoBRAIN | Case report | Single case (patient with pancolitis) | - | N/A | N/A | N/A |

While the application of AI in endoscopy is expanding, its role in the histopathological analysis of IBD and associated neoplasia is equally important. Histopathological examination remains the gold standard for diagnosing dysplasia and cancer; however, it is time-consuming and subject to interobserver variability.

Noguchi et al[35] developed an AI model capable of detecting p53 positivity in tissue samples stained with he

A major strength of this model lies in its cost-effectiveness, as it could reduce the need for additional IHC staining in certain diagnostic workflows. Moreover, its rapid processing capabilities make it a valuable adjunct in busy pathology settings.

While the detection of dysplastic lesions remains a critical goal, AI has demonstrated its greatest clinical impact in GI endoscopy for IBD through the accurate assessment of mucosal inflammation and disease activity, which is essential for guiding therapeutic decisions and monitoring patient outcomes. Several DL algorithms have been developed to classify endoscopic disease severity in UC with high sensitivity and specificity. Ozawa et al[36] developed a CNN-based model trained on over 26000 colonoscopic images, which accurately distinguished between mucosal healing and active inflammation, achieving an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.98 for Mayo scores 0-1[36].

Fan et al[37] designed an AI system capable of assigning both Mayo and UC Endoscopic Index of Severity scores directly from full-length colonoscopy videos. This model provided consistent grading across different colonic segments and generated an integrated visualization of inflammatory distribution[37].

Takenaka et al[38] introduced the “deep neural network system based on endoscopic images of UC” model, an AI-based system capable of predicting both endoscopic and histologic remission without the need for biopsy. The model achieved a sensitivity of 92%, specificity of 91.3%, PPV of 86.2%, and NPV of 95.1%. Notably, this model also correlated with clinical outcomes such as hospitalization and relapse, underscoring its significant prognostic value[38]. Similarly, Iacucci et al[39] created a CNN-based AI system for detecting endoscopic and histologic remission in UC. When applied to WLE, the model achieved a sensitivity of 72% (95%CI: 55%-85%), specificity of 87% (95%CI: 81%-91%), PPV of 53% (95%CI: 43%-63%), NPV of 94% (95%CI: 90%-96%), accuracy of 84% (95%CI: 79%-89%), and an AUROC of 0.85 (95%CI: 0.79-0.90). Enhanced performance was observed using VCE, yielding a sensitivity of 79% (95%CI: 63%-90%), specificity of 95% (95%CI: 91%-98%), PPV of 77% (95%CI: 64%-86%), NPV of 96% (95%CI: 92%-97%), accuracy of 92% (95%CI: 88%-95%), and an AUROC of 0.94 (95%CI: 0.91-0.97)[39].

The first fully automated, real-time AI model for UC activity scoring was developed by Kim et al[40], showing strong agreement with expert assessments (weighted kappa: 0.78-0.90) and effectively addressing the well-known issue of interobserver variability in clinical practice. Maeda et al[41] also highlighted the importance of real-time AI systems in predicting disease relapse in patients with UC who are in clinical remission, an advancement that carries significant clinical implications for proactive disease management.

AI has also shown promise in assessing Crohn’s disease activity and differentiating IBD from other conditions. Yang et al[42] reported AI models that predict UC severity and distinguish Crohn’s disease from Behçet’s disease and intestinal tuberculosis, with sensitivities ranging between 72% and 83% and specificities between 86% and 96%.

Although current evidence highlights the potential of AI to enhance early detection of dysplasia and CRC in patients with IBD, further large-scale, multicenter, prospective studies are needed. Many studies remain preliminary, often limited by small sample sizes, single-center designs, or retrospective methodologies. Furthermore, regulatory agencies and major clinical guidelines, including those from the ECCO and the SCENIC consensus, have yet to fully incorporate AI-assisted technologies into standard surveillance protocols.

Nonetheless, accumulating data suggest that AI - when used as an adjunct to expert interpretation - can significantly improve lesion detection, reduce interobserver variability, and streamline clinical decision-making. As these systems become more sophisticated and widely validated, they are expected to become integral components of IBD surveillance and management, both in endoscopy and histopathology.

Despite promising results, several real-world barriers still limit the widespread implementation of AI in endoscopy for patients with IBD, as well as for other GI indications. One of the major challenges is cost-effectiveness. The integration of AI systems requires significant resources, including specialized software, high-performance hardware, and secure data storage infrastructure. This is particularly problematic in resource-limited settings and in centers with a relatively low patient volume, where the cost–benefit ratio of AI adoption may be less favorable. Another critical limitation is the need for adequate training of both endoscopists and endoscopy assistants. In addition to mastering core endoscopic competencies, clinicians must also understand the basic technical principles of AI, correctly interpret AI-generated outputs, and - most importantly - recognize the limitations of these systems. Closely related to this is the important issue of the medicolegal implications of AI in endoscopy. The legal responsibility for clinical decisions made with AI assistance remains unclear, especially when AI-generated recommendations conflict with the clinician’s judgment. The authors of this review maintain the position that, in any case of discrepancy between AI output and clinical expertise, the final decision should always be based on the physician’s judgment. We believe that it will take considerable time for AI systems to match the comprehensive, contextual clinical evaluation performed by experienced endoscopists.

Workflow integration represents another major challenge. AI tools must be incorporated seamlessly into existing clinical protocols without prolonging the duration or complexity of endoscopic procedures significantly.

When discussing practical constraints, it is essential to consider studies highlighting implementation challenges in the context of IBD. A systematic review by Liu et al[43] demonstrated that many image-based AI models for IBD carry a high risk of bias. Common issues included small sample sizes, poor handling of missing data, and lack of external validation cohorts[43].

Similarly, López-Serrano et al[44] compared the performance of VCE with the CADe Discovery™ AI system for dysplasia detection in patients with UC. While both methods achieved a high sensitivity of 90%, the CADe system showed poor specificity (5%), a very low PPV (2%), and an overall diagnostic accuracy of just 22.9%[44]. These findings suggest that, despite high dysplasia detection rates, the CADe system yielded a substantial number of false positives, potentially limiting its clinical utility. Such negative or limited results underscore that, although AI holds significant promise, its real-world application is often hindered by methodological shortcomings, disease heterogeneity, and a lack of robust validation studies. Future research should address these challenges by incorporating both positive and negative outcomes, ensuring adequate sample sizes, and conducting externally validated, multicenter studies to better evaluate AI performance across diverse clinical environments.

AI has significantly advanced diagnostic, therapeutic, and prognostic methods in gastroenterology. In the context of IBD endoscopy, AI improves diagnostic accuracy by detecting subtle mucosal changes, differentiating UC from Crohn’s disease and non-IBD colitis, and predicting histological remission. It enables faster, more precise decision-making, crucial for dysplasia detection and disease activity assessment, ultimately supporting personalized patient care. Future de

| 1. | Singh N, Bernstein CN. Environmental risk factors for inflammatory bowel disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2022;10:1047-1053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 33.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Da Rio L, Spadaccini M, Parigi TL, Gabbiadini R, Dal Buono A, Busacca A, Maselli R, Fugazza A, Colombo M, Carrara S, Franchellucci G, Alfarone L, Facciorusso A, Hassan C, Repici A, Armuzzi A. Artificial intelligence and inflammatory bowel disease: Where are we going? World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:508-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Sternberg RJ. Human intelligence. [cited 5 September 2025]. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/science/human-intelligence-psychology. |

| 4. | Urquhart SA, Christof M, Coelho-Prabhu N. The impact of artificial intelligence on the endoscopic assessment of inflammatory bowel disease-related neoplasia. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2025;18:17562848251348574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Popovic D, Glisic T, Milosavljevic T, Panic N, Marjanovic-Haljilji M, Mijac D, Stojkovic Lalosevic M, Nestorov J, Dragasevic S, Savic P, Filipovic B. The Importance of Artificial Intelligence in Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:2862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ebigbo A, Palm C, Probst A, Mendel R, Manzeneder J, Prinz F, de Souza LA, Papa JP, Siersema P, Messmann H. A technical review of artificial intelligence as applied to gastrointestinal endoscopy: clarifying the terminology. Endosc Int Open. 2019;7:E1616-E1623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mori Y, Kudo SE, Mohmed HEN, Misawa M, Ogata N, Itoh H, Oda M, Mori K. Artificial intelligence and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: Current status and future perspective. Dig Endosc. 2019;31:378-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jordan MI, Mitchell TM. Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science. 2015;349:255-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2833] [Cited by in RCA: 2155] [Article Influence: 195.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Le Berre C, Sandborn WJ, Aridhi S, Devignes MD, Fournier L, Smaïl-Tabbone M, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Application of Artificial Intelligence to Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:76-94.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 355] [Article Influence: 59.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 10. | Cannarozzi AL, Massimino L, Latiano A, Parigi TL, Giuliani F, Bossa F, Di Brina AL, Ungaro F, Biscaglia G, Danese S, Perri F, Palmieri O. Artificial intelligence: A new tool in the pathologist's armamentarium for the diagnosis of IBD. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2024;23:3407-3417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Urban G, Tripathi P, Alkayali T, Mittal M, Jalali F, Karnes W, Baldi P. Deep Learning Localizes and Identifies Polyps in Real Time With 96% Accuracy in Screening Colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1069-1078.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 398] [Cited by in RCA: 453] [Article Influence: 56.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Guerrero Vinsard D, Fetzer JR, Agrawal U, Singh J, Damani DN, Sivasubramaniam P, Poigai Arunachalam S, Leggett CL, Raffals LE, Coelho-Prabhu N. Development of an artificial intelligence tool for detecting colorectal lesions in inflammatory bowel disease. iGIE. 2023;2:91-101.e6. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yamamoto S, Kinugasa H, Hamada K, Tomiya M, Tanimoto T, Ohto A, Toda A, Takei D, Matsubara M, Suzuki S, Inoue K, Tanaka T, Hiraoka S, Okada H, Kawahara Y. The diagnostic ability to classify neoplasias occurring in inflammatory bowel disease by artificial intelligence and endoscopists: A pilot study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37:1610-1616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fatakhova K, Rajapakse R. From random to precise: updated colon cancer screening and surveillance for inflammatory bowel disease. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;9:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ang TL, Wang LM. Artificial intelligence for the diagnosis of dysplasia in inflammatory bowel diseases. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37:1469-1470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sharma P, Montgomery E. Gastrointestinal dysplasia. Pathology. 2013;45:273-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:S3-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1117] [Cited by in RCA: 1380] [Article Influence: 60.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (13)] |

| 18. | Zhao S, Wang S, Pan P, Xia T, Chang X, Yang X, Guo L, Meng Q, Yang F, Qian W, Xu Z, Wang Y, Wang Z, Gu L, Wang R, Jia F, Yao J, Li Z, Bai Y. Magnitude, Risk Factors, and Factors Associated With Adenoma Miss Rate of Tandem Colonoscopy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1661-1674.e11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 433] [Article Influence: 61.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Kröner PT, Engels MM, Glicksberg BS, Johnson KW, Mzaik O, van Hooft JE, Wallace MB, El-Serag HB, Krittanawong C. Artificial intelligence in gastroenterology: A state-of-the-art review. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:6794-6824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (11)] |

| 20. | Hassan C, Spadaccini M, Iannone A, Maselli R, Jovani M, Chandrasekar VT, Antonelli G, Yu H, Areia M, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Bhandari P, Sharma P, Rex DK, Rösch T, Wallace M, Repici A. Performance of artificial intelligence in colonoscopy for adenoma and polyp detection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93:77-85.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 361] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 70.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 21. | Milosavljevic T, Popovic D, Zec S, Krstic M, Mijac D. Accuracy and Pitfalls in the Assessment of Early Gastrointestinal Lesions. Dig Dis. 2019;37:364-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tanaka S, Kaltenbach T, Chayama K, Soetikno R. High-magnification colonoscopy (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:604-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zammarchi I, Santacroce G, Iacucci M. Next-Generation Endoscopy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:2547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Shahsavari D, Waqar M, Thoguluva Chandrasekar V. Image enhanced colonoscopy: updates and prospects-a review. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | van der Laan JJH, van der Waaij AM, Gabriëls RY, Festen EAM, Dijkstra G, Nagengast WB. Endoscopic imaging in inflammatory bowel disease: current developments and emerging strategies. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;15:115-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Pilonis ND, Januszewicz W, di Pietro M. Confocal laser endomicroscopy in gastro-intestinal endoscopy: technical aspects and clinical applications. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kiesslich R, Goetz M, Lammersdorf K, Schneider C, Burg J, Stolte M, Vieth M, Nafe B, Galle PR, Neurath MF. Chromoscopy-guided endomicroscopy increases the diagnostic yield of intraepithelial neoplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:874-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 383] [Cited by in RCA: 379] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Gordon H, Biancone L, Fiorino G, Katsanos KH, Kopylov U, Al Sulais E, Axelrad JE, Balendran K, Burisch J, de Ridder L, Derikx L, Ellul P, Greuter T, Iacucci M, Di Jiang C, Kapizioni C, Karmiris K, Kirchgesner J, Laharie D, Lobatón T, Molnár T, Noor NM, Rao R, Saibeni S, Scharl M, Vavricka SR, Raine T. ECCO Guidelines on Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Malignancies. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:827-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Laine L, Kaltenbach T, Barkun A, McQuaid KR, Subramanian V, Soetikno R; SCENIC Guideline Development Panel. SCENIC international consensus statement on surveillance and management of dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:639-651.e28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 344] [Cited by in RCA: 417] [Article Influence: 37.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Kamitani Y, Nonaka K, Isomoto H. Current Status and Future Perspectives of Artificial Intelligence in Colonoscopy. J Clin Med. 2022;11:2923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kudo SE, Misawa M, Mori Y, Hotta K, Ohtsuka K, Ikematsu H, Saito Y, Takeda K, Nakamura H, Ichimasa K, Ishigaki T, Toyoshima N, Kudo T, Hayashi T, Wakamura K, Baba T, Ishida F, Inoue H, Itoh H, Oda M, Mori K. Artificial Intelligence-assisted System Improves Endoscopic Identification of Colorectal Neoplasms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:1874-1881.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Abdelrahim M, Siggens K, Iwadate Y, Maeda N, Htet H, Bhandari P. New AI model for neoplasia detection and characterisation in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2024;73:725-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Maeda Y, Kudo SE, Ogata N, Misawa M, Mori Y, Mori K, Ohtsuka K. Can artificial intelligence help to detect dysplasia in patients with ulcerative colitis? Endoscopy. 2021;53:E273-E274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Fukunaga S, Kusaba Y, Ohuchi A, Nagata T, Mitsuyama K, Tsuruta O, Torimura T. Is artificial intelligence a superior diagnostician in ulcerative colitis? Endoscopy. 2021;53:E75-E76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Noguchi T, Ando T, Emoto S, Nozawa H, Kawai K, Sasaki K, Murono K, Kishikawa J, Ishi H, Yokoyama Y, Abe S, Nagai Y, Anzai H, Sonoda H, Hata K, Sasaki T, Ishihara S. Artificial Intelligence Program to Predict p53 Mutations in Ulcerative Colitis-Associated Cancer or Dysplasia. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28:1072-1080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Ozawa T, Ishihara S, Fujishiro M, Saito H, Kumagai Y, Shichijo S, Aoyama K, Tada T. Novel computer-assisted diagnosis system for endoscopic disease activity in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:416-421.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 37. | Fan Y, Mu R, Xu H, Xie C, Zhang Y, Liu L, Wang L, Shi H, Hu Y, Ren J, Qin J, Wang L, Cai S. Novel deep learning-based computer-aided diagnosis system for predicting inflammatory activity in ulcerative colitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;97:335-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Takenaka K, Ohtsuka K, Fujii T, Oshima S, Okamoto R, Watanabe M. Deep Neural Network Accurately Predicts Prognosis of Ulcerative Colitis Using Endoscopic Images. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:2175-2177.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 39. | Iacucci M, Cannatelli R, Parigi TL, Nardone OM, Tontini GE, Labarile N, Buda A, Rimondi A, Bazarova A, Bisschops R, Del Amor R, Meseguer P, Naranjo V, Ghosh S, Grisan E; PICaSSO group. A virtual chromoendoscopy artificial intelligence system to detect endoscopic and histologic activity/remission and predict clinical outcomes in ulcerative colitis. Endoscopy. 2023;55:332-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Kim JH, Choe AR, Park Y, Song EM, Byun JR, Cho MS, Yoo Y, Lee R, Kim JS, Ahn SH, Jung SA. Using a Deep Learning Model to Address Interobserver Variability in the Evaluation of Ulcerative Colitis (UC) Severity. J Pers Med. 2023;13:1584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Maeda Y, Kudo SE, Ogata N, Misawa M, Iacucci M, Homma M, Nemoto T, Takishima K, Mochida K, Miyachi H, Baba T, Mori K, Ohtsuka K, Mori Y. Evaluation in real-time use of artificial intelligence during colonoscopy to predict relapse of ulcerative colitis: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;95:747-756.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Yang LS, Perry E, Shan L, Wilding H, Connell W, Thompson AJ, Taylor ACF, Desmond PV, Holt BA. Clinical application and diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence in colonoscopy for inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review. Endosc Int Open. 2022;10:E1004-E1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Liu X, Reigle J, Prasath VBS, Dhaliwal J. Artificial intelligence image-based prediction models in IBD exhibit high risk of bias: A systematic review. Comput Biol Med. 2024;171:108093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | López-Serrano A, Voces A, Lorente JR, Santonja FJ, Algarra A, Latorre P, Del Pozo P, Paredes JM. Artificial intelligence for dysplasia detection during surveillance colonoscopy in patients with ulcerative colitis: A cross-sectional, non-inferiority, diagnostic test comparison study. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;48:502210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/