Published online Jan 16, 2026. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v18.i1.115392

Revised: November 6, 2025

Accepted: November 25, 2025

Published online: January 16, 2026

Processing time: 91 Days and 15.8 Hours

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has emerged as a key diagnostic and therapeutic modality due to its minimally invasive nature and high success rates. It is widely used for diagnosing and staging gastrointestinal (GI), pancreatobiliary, and lung malignancies. EUS-guided fine needle biopsy (EUS-FNB) provides preserved tissue architecture, improving histological diagnosis for such conditions. The elderly are at significantly higher risk of GI lesions, being ten times more prone to malignancy and experiencing higher mortality, thereby requiring safer and less invasive diagnostic approaches. Despite its increasing use, evidence on EUS-FNB safety and diagnostic yield in geriatric population, particularly from resource-limited settings, remains limited.

To assess the indications, diagnostic efficacy, and safety profile of EUS-FNB in the geriatric population.

This single-centre retrospective study included patients aged 65 years or above who underwent EUS-guided biopsy between June 2020 and June 2022 at Aga Khan University Hospital, a tertiary care centre in Karachi, Pakistan. Patient demographics, procedural details including lesion site, number of needle passes, needle type, and tissue acquisition technique, along with histopathological diagnosis, were extracted from medical records. Data were analysed using SPSS, with categorical variables reported as frequencies and per

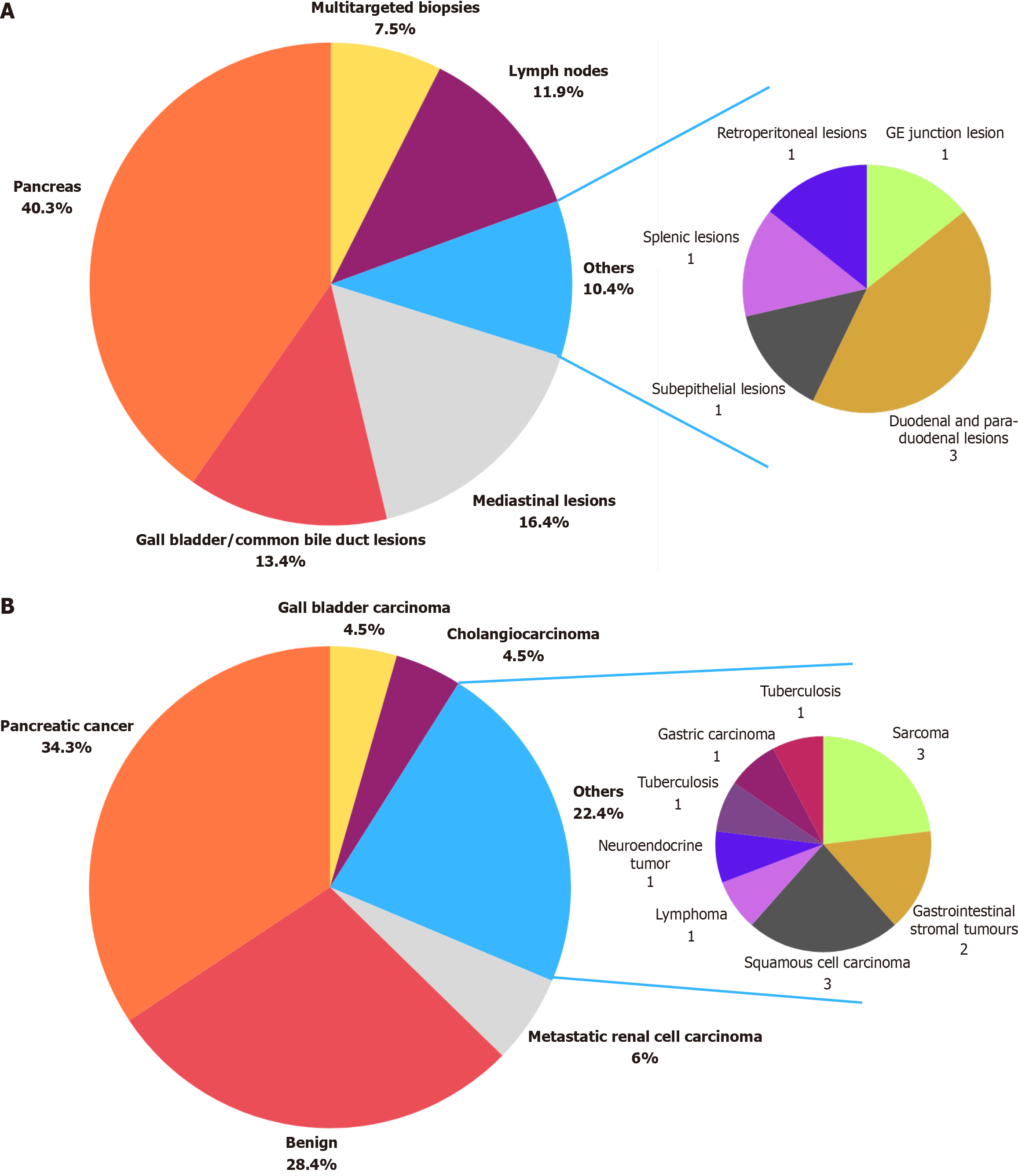

A total of 67 elderly patients were included, with a mean age of 72.7 ± 6.33 years; most were male (72%). The median duration of the EUS procedure was 19 (23) minutes. Most patients underwent biopsy for pancreatic lesions (40.3%), followed by mediastinal (16.4%) and gallbladder/common bile duct lesions (13.4%). In 31.4% cases, the specimen was obtained with 2 needle passes, while 41.4% required 1 pass and 22.9% required 3 passes. Multi-targeted biopsies using a single pass were performed in 7.5% cases. A Franseen-design needle was used in all cases, with 22G utilized in 92.5% and 25G in 7.5%. Diagnostic adequacy was 100%, with no procedure-related complications. Histopathology revealed pancreatic cancer (34.3%), benign lesions (28.4%), and metastatic renal carcinoma (6%).

EUS-FNB is an effective minimally invasive diagnostic tool in elderly, demonstrating high diagnostic adequacy without complications. Future studies are warranted to further validate its safety and effectiveness in this popu

Core Tip: This retrospective study evaluates the diagnostic yield and safety of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle biopsy (EUS-FNB) in elderly patients with gastrointestinal lesions at a tertiary care centre in Pakistan. Using the Franseen needle and macroscopic on-site evaluation, EUS-FNB achieved 100% technical success and diagnostic yield with no reported procedural related complications. The median of two needle passes along with shorter average procedure time, making it highly feasible for the geriatric population. These findings support EUS-FNB as a safe, efficient, and minimally invasive alternative for tissue diagnosis in elderly patients, even in resource-constrained settings.

- Citation: Sohail Z, Jamal A, Karim MM, Ayesha S, Shahid AH, Musharraf MB, Uddin Z, Rehman AU. Evaluating the safety and diagnostic performance of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy in the geriatric population. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2026; 18(1): 115392

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v18/i1/115392.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v18.i1.115392

Introduced in the 1980s, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has been used as a diagnostic as well as a therapeutic modality in various conditions owing to its minimally invasive technique and high success rates[1]. EUS is being commonly used in diagnosis and staging of gastrointestinal (GI), pancreato-biliary and lung malignancy. It has become a well-established technique in acquiring tissue specimens for pancreatic and non-pancreatic lesions[2-5]. Moreover, therapeutic inter

Elderly individuals aged 65 years and above represent a high-risk group for GI lesions, exhibiting a tenfold increased likelihood of developing malignancies and a sixteenfold higher mortality risk compared to younger populations[6,7]. EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) has played an essential role in diagnosing and managing these patients with a high specificity, sensitivity and a diagnostic accuracy of 78%-98%[8]. However, EUS-FNA is limited by its inability to obtain preserved core tissue architecture, which is essential for immunohistochemical staining and accurate diagnosis of lesions such as lymphoma, GI stromal tumor (GIST), and autoimmune pancreatitis[9]. On the contrary, EUS-guided fine needle biopsy (EUS-FNB) has been studied to obtain histological samples of tissues yielding greater diagnostic efficacy[10].

EUS-FNA with rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE) has been standardized for tissue sampling in EUS; however, the introduction of EUS-FNB has also encouraged the use of macroscopic on-site evaluation (MOSE) for tissue samples[8]. Introduced by Iwashita et al[11], MOSE performed by the endosonographer has proven to be a successful technique for obtaining tissue specimens, achieving a diagnostic yield of 89%. It has become increasingly popular due to the simplicity of the technique and the added advantage of cost-effectiveness[8,11].

Although several studies have evaluated the safety and diagnostic performance of EUS in elderly patients, most have focused on EUS-FNA rather than EUS-FNB. For instance, Attila and Faigel[12] assessed the safety of EUS in patients over 80 years, and Takahashi et al[13] evaluated EUS-FNA for pancreatic solid masses in an elderly cohort, both demonstrating acceptable safety profiles but without reporting tissue core adequacy or histologic yield. Only one small retrospective study by Lai et al[14] specifically examined EUS-FNB in elderly patients (n = 41, ≥ 70 years) focusing on retroperitoneal and GI tumors; however, it was limited by its small sample size and single-center design in a high-income setting. Larger series of EUS-FNB by Zhang et al[15] have included elderly patients within mixed-age cohorts but have not stratified outcomes by age or addressed geriatric-specific risks. Furthermore, no published data are available from low- and middle-income countries evaluating the safety, feasibility, and diagnostic yield of EUS-FNB exclusively in geriatric populations. This significant evidence gap highlights the novelty and relevance of our study, which evaluates the indications, diagnostic yield, and safety of EUS-FNB in elderly patients within a resource-constrained tertiary care setting.

This single-centre retrospective observational study was conducted in the gastroenterology section of the Department of Medicine at Aga Khan University Hospital, a tertiary care hospital in Karachi, Pakistan. It included consecutive inpatient and outpatient patients who aged 65 years of age or above, of either gender, who underwent EUS-FNB at the endoscopy suite unit from June 2020 to June 2022. The exclusion criteria for this study comprised patients with incomplete de

The EUS procedure was performed in a negative pressure room following all institutional standard operating procedures to ensure patient and staff safety. A minimal number of personnel were present to maintain aseptic conditions and minimize the risk of infection. All procedures were conducted under conscious sedation, with patients positioned in the left lateral position. Conscious sedation was achieved using intravenous midazolam (1-3 mg; 0.02-0.05 mg/kg), titrated to the desired clinical effect. Patients were continuously monitored for oxygen saturation, heart rate, and blood pressure throughout the procedure, with supplemental oxygen administered at 2-4 L/minute via nasal cannula. Pre-procedural assessment included documentation of comorbidities and classification according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status I-III. An anesthesiologist remained on standby during all procedures, and emergency equipment and resuscitation drugs were readily available in accordance with institutional policy. Antithrombotic therapy was managed according to the joint European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines for endoscopy in patients receiving antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy[16]. Aspirin monotherapy was continued, while P2Y12 inhibitors (e.g., clopidogrel, ticagrelor) were withheld for five days prior to the procedure. Warfarin was discontinued five days before EUS, with a target international normalized ratio < 1.5, and bridging with therapeutic-dose low-molecular-weight heparin was initiated during this interval and stopped 12-24 hours before the procedure. Direct oral anticoagulants were withheld for 48-72 hours, depending on renal function.

All procedures were performed using a PENTAX Medical Ultrasound Video Gastroscope (EUS-J10) connected to the Hitachi HI VISION Avius ultrasound system. The puncture route (transgastric, transduodenal, or transesophageal) was selected based on the location and accessibility of the target lesion. EUS-FNB was conducted under real-time ultrasound and Doppler guidance to avoid intervening vessels. Tissue acquisition was performed using Boston Scientific’s AcquireTM Fine Needle Biopsy device equipped with a Franseen needle of either 22-gauge or 25-gauge, depending on the lesion site and operator preference. The “slow-pull” technique was employed in most cases, wherein the stylet was gradually withdrawn while the needle was moved back and forth within the lesion under continuous real-time imaging. Each lesion was typically sampled with one to three needle passes until a visible core fragment was obtained on MOSE.

MOSE was conducted immediately after each EUS-FNB procedure by a senior gastroenterologist with over 10 years of independent experience in diagnostic and interventional EUS. The operator was credentialed for EUS-FNB at the institution, having completed formal fellowship training in advanced endoscopy, and had also received institutional training in MOSE interpretation based on the criteria described by Iwashita et al[11]. Each specimen was visually inspected on-site for the presence of a whitish or yellowish “core” tissue fragment distinguishable from blood clots. A sample was considered macroscopically adequate if a visible core measuring at least 4-5 mm was identified. Adequate specimens were fixed in formalin and sent for histopathological evaluation. The MOSE assessment was recorded as either adequate or inadequate according to these objective visual criteria. Diagnostic adequacy on final histopathology was subsequently correlated with MOSE findings to assess procedural accuracy. All cases yielded adequate samples for histopathological diagnosis.

Post-procedure, all patients were given oral antibiotics and observed in the recovery area for 2-3 hours to monitor for any early complications. No sedation-related adverse events were recorded. Antithrombotic agents were resumed 24 hours after the procedure, provided there was no evidence of post-procedural bleeding. High-risk cardiac or thromboembolic patients were managed in consultation with the cardiology service. Notably, no bleeding or thromboembolic complications were encountered in this study.

Patient data were extracted from health records accessed through the electronic medical records and patient files maintained at the institutional health information management system department, after obtaining approval from the institutional ethical review committee. The reviewed data included patient demographics such as age and gender, indication for EUS-FNB, procedural details and histopathological diagnosis. The procedural details included the lesion site, total number of needle passes, type of fine needle biopsy used (22-gauge or 25-gauge), technique of tissue ac

The primary outcomes of the study were diagnostic adequacy and procedure-related complications. Diagnostic adequacy was defined as the acquisition of a core tissue sample sufficient to establish a definitive histopathological diagnosis, as verified by the reporting pathologist. Samples categorized as “non-diagnostic” or “insufficient” were deemed inadequate. Procedure-related complications were assessed based on both timing and severity. Early complications, including bleeding, perforation, abdominal pain, or sedation-related events, were defined as those occurring during the procedure or within the immediate 2-3-hour post-procedure observation period. Delayed complications, such as pancreatitis, infection, delayed bleeding, or post-procedural pain, were defined as those occurring within seven days after EUS-FNB and were identified through review of electronic medical records and outpatient follow-up documentation. The severity of complications was classified according to the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy lexicon as mild (self-limiting, requiring no intervention), moderate (requiring hospitalization or endoscopic/radiologic intervention), or severe (associated with significant morbidity, surgical intervention, or death)[17].

All descriptive statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS version 23. Descriptive data were obtained, with categorical variables such as gender, indication for EUS, number of needle passes, needle type, and definitive diagnosis reported as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables, including age, were expressed as mean ± SD due to normal distribution, while procedural duration was presented as median with interquartile range owing to non-normal distribution, as determined using histograms and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

The study was approved by the institutional ethical review committee of Aga Khan University Hospital (Approval No. 6874-25427). All patient identifiers were removed during data entry, and complete confidentiality was maintained throughout the study.

A total of 67 elderly patients who underwent EUS-FNB biopsy during specified timeframe were included in our study. All patients were adults aged 65 years or older, ranging from 65 to 90 years. The mean age of the patients was 72.7 ± 6.3 years, with 72% (n = 48) being males and 28% (n = 19) females. The median duration of EUS procedure was 19 (23) minutes (Table 1).

| Variables | n | Percentage (%) |

| Total | 67 | 100 |

| Age (year), mean ± SD | 72.7 ± 6.3 (range: 65-90) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 48 | 72 |

| Female | 19 | 28 |

| EUS procedural duration (minutes), median (IQR) | 19 (23) | |

| Needle type | ||

| 22G | 62 | 92.5 |

| 25G | 5 | 7.5 |

| Needle passes, median (IQR) | 2 (1) | |

| Number of “needle” passes | ||

| 1 | 29 | 43.3 |

| 2 | 22 | 32.8 |

| 3 | 16 | 23.9 |

| EUS diagnostic yield | ||

| Sufficient to conclude diagnosis | 67 | 100 |

| EUS procedure related complications | 0 | 0 |

During the EUS procedure, specific tissue lesions or multiple lesions were targeted for biopsy based on the indication for EUS, as shown in Figure 1A. In our study, the majority of patients underwent pancreatic biopsies (40.3%, n = 27), followed by those with mediastinal lesions (16.4%, n = 11) and gallbladder or common bile duct lesions (13.4%, n = 9). Lymph node biopsies were performed in 11.9% (n = 8) of patients, while 4.5% (n = 3) had duodenal or para-duodenal lesions. Additionally, one patient each underwent EUS-FNB for a gastroesophageal junction lesion, a retroperitoneal lesion, a splenic lesion, and a subepithelial lesion.

The median number of needle passes was found to be 2.0 (1.0). In 31.4% (n = 22) cases, biopsy specimen was obtained on 2 needle passes. In 41.4% (n = 29) patients, biopsy was taken with single needle pass while 3 needle passes were done in 22.9% cases (n = 16). Among these, in 7.5% of cases (n = 5), multi targeted biopsies were obtained with a single needle pass. A Franseen design (Boston scientific aquire) needle was used in all cases, with 22G needle utilized in 92.5% (n = 62) and 25G needles in 7.5% (n = 5) cases. Subsequently, all patients underwent EUS-FNB under conscious sedation, with no post-procedural complications reported, achieving a 100% technical success and diagnostic yield (Table 1).

Upon histopathological analysis, the definitive tissue diagnoses were established and shown in Figure 1B. In our study, the most common definitive tissue diagnosis was found to be pancreatic cancer reported in 34.3% (n = 23), followed by benign lesion in 28.4% (n = 19) and metastatic renal cell carcinoma in 6.0% (n = 4). Additionally, squamous cell carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, gall bladder carcinoma, sarcoma and neuroendocrine tumors were each reported in 4.5% (n = 3) cases. GIST diagnosis was established in 3.0% (n = 2) of cases. Moreover, lymphoma, Tuberculosis, lung adenocarcinoma and gastric carcinoma were each identified in 1.5% (n = 1).

This retrospective study evaluated the diagnostic yield and safety of EUS-FNB in the geriatric population presenting to a tertiary care centre with GI lesions suspicious for malignancy. Although elderly patients constitute a major proportion of those undergoing this procedure, the safety and efficacy of EUS-FNB in this age group have been rarely assessed, with most reports focusing on EUS-FNA. A previous study by Attila and Faigel[12] reported 232 elderly patients aged above 80 years who underwent EUS-FNA over a 9-year period to assess procedural safety and clinical utility, whereas a study by Takahashi et al[13] included 600 elderly patients who underwent EUS-FNA over a 6-year period. In comparison, our study included 67 patients aged 65 years or older who underwent EUS-FNB over a 2-year period, representing a substantial number of cases given our role as a tertiary referral centre. This contrasts with the study by Lai et al[14], which reported only 41 patients aged ≥ 70 years who underwent EUS-FNB over a period exceeding two years. This study showed a female predominance around 58.5% females, whereas the study by Attila and Faigel[12] reported 60.3% females. In contrast, our study reported only 28% females, while the study by Takahashi et al[13] showed relatively higher proportion of males, with males comprising 57.1% of their cohort.

Most of our patients underwent pancreatic biopsies, with 34.3% of the cases diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, whereas study by Lai et al[14] reported 60.9% patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. In contrast, Takahashi et al[13] showed greater patients with pancreatic cancer around 91.7% cases. In a population-based study of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, Ngamruengphong et al[18] compared patients aged 65 and older who underwent EUS for diagnosis with those who did not. The study found that EUS was associated with earlier diagnosis, more timely interventions, and improved clinical outcomes in this patient population.

Routine administration of moderate sedation regimens with midazolam has shown to be more effective in endoscopic procedures with better procedural tolerance[19]. As reported by Amornyotin et al[20], various sedation regimens can be safely administered for invasive endoscopic procedures, provided that adequate monitoring and supervision by an anesthetist are ensured. In our study however, we only used conscious sedation under midazolam for EUS-FNB rendering it safe and adequate for this procedure.

EUS-FNB showed better diagnostic adequacy and preserved tissue architecture, allowing for additional immunohistochemical staining compared to EUS-FNA[21]. The number of needle passes required to obtain an adequate sample is an important factor influencing procedural ease, tissue yield and safety. EUS-FNB usually requires fewer punctures and needle passes than EUS-FNA, making the procedure easier and safer[14]. Our study showed a median of 2.0 (1.0) needle passes, with only 22.9% of cases requiring three passes to obtain a sample. In comparison, Takahashi et al[13] reported a median of three needle passes for EUS-FNA, while Lai et al[14] found a mean of 3.27 ± 1.34 for EUS-FNB. Fewer needle passes help shorten the EUS procedure duration, which is especially beneficial for elderly patients those with significant comorbidities. Similarly, the mean EUS-FNB procedure duration in our study was 19 (23) minutes, compared to the median 46 minutes reported for EUS-FNA by Takahashi et al[13]. This also contributes to higher technical success, as reflected in our study’s finding showing 100% success rate.

Our study reported no early or late complications following EUS-FNB in elderly patients, suggesting that it is a safe modality for obtaining tissue diagnoses in suspected malignancy. A study by Benson et al[22] reported a 4.8% risk of EUS-related complications in the elderly population; However, only 18% of those patients underwent fine-needle aspiration. Similarly, a study conducted about a decade earlier by Kurt et al[23] reported a higher complication rate of 36.4% in patients over 60 years of age, although only 4.9% underwent fine-needle aspiration. In contrast, our study specifically focused on EUS-guided FNB in the geriatric population and reported no complications. Meanwhile, in the study by Lai et al[14], the incidence of post-EUS-FNB complications was 0.8%, with one patient developing mild pancreatitis that resolved within three days.

The accuracy of tissue sample collected via EUS-FNB has been found sufficient to establish definitive diagnosis upon histopathological evaluation, achieving 100% diagnostic yield. Whereas study by Lai et al[14] showed 92.4% diagnostic accuracy. We used MOSE for the collected specimens. This technique has been recently introduced and has shown comparable accuracy to the traditionally used ROSE for tissue diagnosis. A prospective randomized controlled study reported that the diagnostic yield of the MOSE technique was 92.6%, which was comparable to that of the conventional EUS-FNA technique[24]. Similar findings were reported by Pausawasdi et al[25], who assessed the diagnostic accuracy of the 22-gauge Franseen needle using the slow pull technique and tissue evaluation with MOSE. Their study demonstrated a 100% technical success rate and 89% histopathological accuracy. Given the likelihood of elderly population being more susceptible to malignant lesions, there is a greater use of EUS guided biopsy in this age group. Hence, there is a need for larger longitudinal studies to evaluate the effectiveness of EUS-FNB for tissue acquisition and diagnostic purposes.

Additionally, we acknowledge certain limitations of our study. One major limitation is its retrospective design. Moreover, the relatively small sample size, restricted study period, and absence of a control group limited our ability to fully evaluate its effectiveness and potential long-term minor or major EUS-related complications. As a single-centre study, the findings may not be fully generalizable, highlighting the need for larger, multi-centre, prospective investigations to validate these observations. Nevertheless, certain methodological strengths should also be noted. All procedures were performed by a single experienced operator using the same type of echoendoscope, ultrasound processor, and needle system to ensure uniformity in technique, patient preparation, sedation, sampling method, and MOSE. While this approach minimized procedural variability, eliminated the influence of a learning curve, and strengthened the internal validity of our study, it may have introduced operator bias, which we acknowledge as one of our study’s limitations.

This study demonstrated that EUS-FNB has a favourable safety profile in elderly patients, with high diagnostic adequacy and no procedure-related complications observed at our tertiary care centre. It represents a simple, cost-effective, and minimally invasive method for tissue sampling in geriatric patients, reducing the need for more invasive procedures. However, the retrospective design, modest sample size, and absence of a comparative control group limit definitive conclusions and warrant cautious interpretation. Larger prospective multi-centre studies are needed to further validate the safety, diagnostic yield, and long-term outcomes of EUS-FNB in elderly patients, particularly in low- and middle-income settings.

| 1. | Sooklal S, Chahal P. Endoscopic Ultrasound. Surg Clin North Am. 2020;100:1133-1150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | LeBlanc JK, DeWitt J, Sherman S. Endoscopic ultrasound: how does it aid the surgeon? Adv Surg. 2007;41:17-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chang KJ, Nguyen P, Erickson RA, Durbin TE, Katz KD. The clinical utility of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis and staging of pancreatic carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:387-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 447] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Varadarajulu S, Eloubeidi MA. The role of endoscopic ultrasonography in the evaluation of pancreatico-biliary cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90:251-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chhieng DC, Jhala D, Jhala N, Eltoum I, Chen VK, Vickers S, Heslin MJ, Wilcox CM, Eloubeidi MA. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy: a study of 103 cases. Cancer. 2002;96:232-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Berger NA, Savvides P, Koroukian SM, Kahana EF, Deimling GT, Rose JH, Bowman KF, Miller RH. Cancer in the elderly. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2006;117:147-156. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Mangiavillano B, Frazzoni L, Togliani T, Fabbri C, Tarantino I, De Luca L, Staiano T, Binda C, Signoretti M, Eusebi LH, Auriemma F, Lamonaca L, Paduano D, Di Leo M, Carrara S, Fuccio L, Repici A. Macroscopic on-site evaluation (MOSE) of specimens from solid lesions acquired during EUS-FNB: multicenter study and comparison between needle gauges. Endosc Int Open. 2021;9:E901-E906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | de Jong JJ, Lantinga MA, Thijs IME, de Reuver PR, Drenth JPH. Systematic review with meta-analysis: age-related malignancy detection rates at upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2020;13:1756284820959225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Alatawi A, Beuvon F, Grabar S, Leblanc S, Chaussade S, Terris B, Barret M, Prat F. Comparison of 22G reverse-beveled versus standard needle for endoscopic ultrasound-guided sampling of solid pancreatic lesions. United European Gastroenterol J. 2015;3:343-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bang JY, Kirtane S, Krall K, Navaneethan U, Hasan M, Hawes R, Varadarajulu S. In memoriam: Fine-needle aspiration, birth: Fine-needle biopsy: The changing trend in endoscopic ultrasound-guided tissue acquisition. Dig Endosc. 2019;31:197-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Iwashita T, Yasuda I, Mukai T, Doi S, Nakashima M, Uemura S, Mabuchi M, Shimizu M, Hatano Y, Hara A, Moriwaki H. Macroscopic on-site quality evaluation of biopsy specimens to improve the diagnostic accuracy during EUS-guided FNA using a 19-gauge needle for solid lesions: a single-center prospective pilot study (MOSE study). Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:177-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Attila T, Faigel DO. Endoscopic ultrasound in patients over 80 years old. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:3065-3071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Takahashi K, Ohyama H, Takiguchi Y, Sekine Y, Toyama S, Yamada N, Sugihara C, Kan M, Ouchi M, Nagashima H, Iino Y, Kusakabe Y, Okitsu K, Ohno I, Kato N. Safety of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration for pancreatic solid mass in the elderly: A single-center retrospective study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2023;23:836-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lai JH, Lin HH, Chen MJ, Lin CC. Safety and Effectiveness of Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine Needle Biopsy for Retroperitoneal and Gastrointestinal Tumors in Elderly Patients. Int J Gerontol. 2022;16:254-256. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Zhang S, Liu J, Wang X, Buryanek J, Thosani N, Thomas-Ogunniyi J. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Biopsy (EUS-FNB): The Experience of 1025 Cases from a Single Academic Center. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2023;12:S51-S52. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Veitch AM, Radaelli F, Alikhan R, Dumonceau JM, Eaton D, Jerrome J, Lester W, Nylander D, Thoufeeq M, Vanbiervliet G, Wilkinson JR, Van Hooft JE. Endoscopy in patients on antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy: British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline update. Gut. 2021;70:1611-1628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 25.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cotton PB, Eisen GM, Aabakken L, Baron TH, Hutter MM, Jacobson BC, Mergener K, Nemcek A Jr, Petersen BT, Petrini JL, Pike IM, Rabeneck L, Romagnuolo J, Vargo JJ. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE workshop. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:446-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1238] [Cited by in RCA: 2021] [Article Influence: 126.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Ngamruengphong S, Li F, Zhou Y, Chak A, Cooper GS, Das A. EUS and survival in patients with pancreatic cancer: a population-based study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:78-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | McQuaid KR, Laine L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials of moderate sedation for routine endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:910-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 376] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Amornyotin S, Leelakusolvong S, Chalayonnawin W, Kongphlay S. Age-dependent safety analysis of propofol-based deep sedation for ERCP and EUS procedures at an endoscopy training center in a developing country. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2012;5:123-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ayesha S, Karim MM, Shahid AH, Rehman AU, Uddin Z, Abid S. Diagnostic role of endoscopic ultrasonography in defining the clinical features and histopathological spectrum of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2025;17:104539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 22. | Benson ME, Byrne S, Brust DJ, Manning B 3rd, Pfau PR, Frick TJ, Reichelderfer M, Gopal DV. EUS and ERCP complication rates are not increased in elderly patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3278-3283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kurt M, Oguz D, Oztas E, Kalkan IH, Sayilir A, Beyazit Y, Sasmaz N. Safety of endoscopic ultrasonography in elderly patients: a single center prospective trial. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2013;25:571-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chong CCN, Lakhtakia S, Nguyen N, Hara K, Chan WK, Puri R, Almadi MA, Ang TL, Kwek A, Yasuda I, Doi S, Kida M, Wang HP, Cheng TY, Jiang Q, Yang A, Chan AWH, Chan S, Tang R, Iwashita T, Teoh AYB. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided tissue acquisition with or without macroscopic on-site evaluation: randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2020;52:856-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Pausawasdi N, Cheirsilpa K, Chalermwai W, Asokan I, Sriprayoon T, Charatcharoenwitthaya P. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Biopsy Using 22G Franseen Needles without Rapid On-Site Evaluation for Diagnosis of Intraabdominal Masses. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/