Published online Jan 16, 2026. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v18.i1.113788

Revised: October 29, 2025

Accepted: December 4, 2025

Published online: January 16, 2026

Processing time: 133 Days and 9.8 Hours

Prospective data have shown the benefit of rectal indomethacin (IND) in pre

To assess the efficacy of IND, with or without a bolus of LR, in patients at a high risk for PEP.

In this randomized, double-blinded controlled trial, we assigned patients to LR, IND, or LR + IND. Each liter of fluid infusion was completed within 30 minutes. Patients were determined to be high-risk based on established criteria and ex

The study sample included 210 patients (70 per group) who accomplished follow-up at 24 hours and 30 days post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. All patients presented at least one high-risk factor for PEP, with 59% having more than one. PEP was observed in 23 patients (10,9%): Five patients (7%) in the LR + IND group vs twelve patients (17%) in the LR group (P = 0.04) and six patients (8%) in the IND group (P = 0.06). Readmission rates were reduced in the LR + IND group [2 (2%)] vs the LR group [7 (10%); P = 0.03]. No differences were seen among the other study groups. One case of severe acute pancreatitis was reported, with two cases in the LR group and one in the IND group.

In high-risk patients for PEP, the combination of LR + IND decreased the incidence of PEP and readmission rates compared to LR or IND administered alone.

Core Tip: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography is an important technique for the diagnosis and treatment of pancreaticobiliary disorders. Post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis (PEP) is the most prevalent complication relating to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Rectal nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and prophylactic pancreatic stent insertion remain advised for its prevention. The administration of lactated Ringer’s solution (LR) plays an important part in preventing pancreatic necrosis and organ failure by sustaining steady pancreatic microcirculation. This randomized, double-blind, controlled study showed that the infusion of LR combined with rectal indomethacin (IND) may decrease the occurrence of PEP and post-procedure readmission in high-risk patients, compared to LR or IND administered separately.

- Citation: Amalou K, Benboudiaf N, Medkour MT, Belghanem F, Chetroub H, Rekab R, Belloula A, Bouaouina F, Saidani K. Lactated Ringer’s solution in combination with indomethacin for prevention of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: A prospective, randomized trial. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2026; 18(1): 113788

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v18/i1/113788.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v18.i1.113788

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is an important technique for diagnosing and managing diseases of the pancreaticobiliary tract. ERCP is linked to several adverse events (AEs), including bleeding, perforation, and acute pancreatitis (AP). Post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) is the most common AE of ERCP[1].

The prevalence of PEP was 9.7% among all patients and 14.7% among high-risk patients in an exhaustive review of patients enrolled in a randomized controlled trial[2]. To reduce the risk of PEP, various pharmacologic interventions and procedural techniques have been studied. Current recommendations for its prevention include the insertion of prophylactic pancreatic stents and the use of rectal nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs)[3,4]. The use of rectal NSAIDs significantly decreases the overall incidence of PEP in different meta-analyses reported recently[5-8]. NSAIDs are potent inhibitors of phospholipase A2, cyclooxygenase, and neutrophil-endothelial interactions, which have been pro

The administration of lactated Ringer’s solution (LR) seems to play a significant role in preventing pancreatic necrosis and organ failure by preserving stable pancreatic microcirculation[15-17]. Aggressive hydration with LR has demon

In the present study, we aimed to assess the efficacy of indomethacin (IND) with or without bolus LR in patients at high risk to prevent PEP.

Patients participating in this randomized, double-blinded controlled trial were enrolled at a tertiary care center in Algeria. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by our institution's scientific committee. This trial was registered online at the Pan African Clinical Trials Registry before the enrollment of any patients.

This trial was performed on high-risk patients who underwent ERCP between October 2021 and August 2023. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before commencing study participation and undergoing ERCP.

Eligible patients included those with intact papillae who were scheduled to undergo ERCP and were deemed high risk according to standard criteria[21,26,27]. Patients were included if they had a history of PEP or were scheduled for a high-risk endoscopic intervention prior to the surgery. Major criteria included a personal history of PEP, suspicion of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, more than 8 cannulation attempts, endoscopic papillary balloon dilation of an intact sphincter, pre-cut sphincterotomy, and endoscopic pancreatic duct (PD) sphincterotomy. Patients were additionally eligible if they met two or more of the following minor criteria: (1) Personal history of recurrent AP; (2) Age under 50 years; (3) Female sex; (4) PD injection resulting in "acinarization" or more than three PD injections; and (5) PD cytology acquisition. Initial demographic information was gathered, including the patient's gender, age, medical history, prior ERCP data, and any AEs that occurred. Before their ERCP, all patients had laboratory data collected, including the basic metabolic panel and lipase levels.

The exclusion criteria included age younger than 18 years, pregnancy or possibility of pregnancy, heart failure higher than New York Heart Association Class II, a history of gastrectomy with Billroth I and II or Roux-en-Y reconstruction, and inability to reach the papilla because of gastroduodenal obstruction and active AP. NSAID-related exclusion criteria included true documented allergy to NSAIDs, use of NSAIDs the day of the procedure, acute renal failure (ARF), or creatinine > 1.2 mg/dL, and active peptic ulcer disease. Contraindications to aggressive intravenous fluid (IVF) hydration were also used as exclusion criteria: (1) Evidence of clinical volume overload (peripheral or pulmonary edema); (2) Respiratory compromise (oxygen saturation < 90% on room air); (3) Chronic kidney disease (creatinine clearance under 40 mL/minute); (4) Systolic congestive heart failure (ejection fraction of under 45%); (5) Cirrhosis; and (6) Severe electrolyte disturbance with sodium < 130 mEq/L or > 150 mEq/L. Patients were also excluded if they did not undergo a planned high-risk intervention and possessed no complete criterion that placed them at high risk for PEP.

After enrollment, patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1 ratio to one of three treatment groups: (1) Rectal IND; (2) LR; and (3) LR + IND. The randomization schedule was created by a computerized random number generator.

ERCP procedures were carried out by experienced therapeutic endoscopists (> 200 patients per year). ERCP was performed on all patients using normal cannulation procedures and a side-viewing duodenoscope. The transpapillary method was used for 10 minutes to attempt selective biliary and pancreatic cannulation with a conventional cannula and a pull-type sphincterotome. Following successful selective deep cannulation, contrast media was administered. If wire-directed cannulation failed within 10 minutes, pre-cut access was attempted as a last resort. The endoscopist chose the type of precut access and whether to employ a pancreatic stent.

The patients were randomly assigned to the three groups (1:1:1) who received aggressive hydration with intravenous LR in an initial bolus of 5 mL/kg concurrently at the start of ERCP and continuously during the procedure, with the maximum hydration being 1 L. Then, hydration with intravenous LR continued at a rate of 3 mL/kg/hour for 8 hours after the procedure or rectal IND or both. Before the procedure, the nurse opens a numbered, bespoke envelope to ensure that both the endoscopist and the patient are blinded.

To monitor for AEs, routine blood examinations with complete blood count and biochemistry, including serum lipase, were performed twice: Once before the procedure and 8-18 hours after the procedure. In patients with suspected/definite PEP, computed tomography was performed as needed.

The primary study outcome was PEP, defined as new or worsening epigastric pain lasting at least 24 hours after ERCP and an increase in pancreatic enzymes greater than three times the upper limit of normal within 24 hours after the procedure, and the resultant or prolonged existing hospitalization of > 2 nights[28,29]. Severity of pancreatitis was defined according to the revised Atlanta classification[30].

Secondary outcomes included severe AP, localized AEs (pseudocyst formation, walled-off pancreatic necrosis, and abscess), death, length of stay in days, and readmission within 30 days[30]. AEs associated with the trial were reported, including NSAID-related anaphylaxis, gastrointestinal bleeding, and ARF. AEs associated with IVF were also observed, including peripheral/pulmonary edema, hypoxia, congestive heart failure aggravation, and ascites. Severe AP was defined as a persistent organ failure not resolved within 48 hours[30].

To track all outcomes, subjects completed a pain severity assessment using a 10-point Likert scale before ERCP and two hours, 24 hours, and 30 days after. All patients were retained in the recovery area for two hours following their ERCP, and those who had worsening abdominal pain from baseline were admitted. To guarantee comprehensive data collection, participants received a phone call or in-person contact (when hospitalized) within 24 hours and again 30 days after their ERCP.

Based on the incidence rate of PEP in the previous report, we assumed an 11.1% incidence rate of pancreatitis in the standard LR group[26] and a decrease up to 5.1% in the aggressive hydration group. We therefore estimated that 68 patients per group were needed, with an 11% incidence of PEP, an expected value of 5%, and alpha (one-sided) and beta values of 0.025 and 0.2, respectively. The consent rate for participation in the trial was expected to be 80%, requiring about 220 patients.

A total of 210 participants (or 70 in each group) were required to identify a difference in PEP incidences of 0.19 in the LR group vs 0.05 in the LR + IND group using the Fisher exact test, assuming a medium effect size with 80% power. Based on previous research, a 0.19 difference in PEP rates across groups was used. Elmunzer et al[31] showed a 0.08 decrease with rectal IND, while Buxbaum et al[25] found a 0.17 decrease with LR infusion. Descriptive statistics were employed to characterize demographic information including age, gender, race and duration of stay, as well as diagnosis and illness features such as ERCP causes, disease intervention, pain, and outcome parameters. Data tables were created for the variables, including means, SD, medians, interquartile range, and 95%CI. The Fisher exact test was used to determine the primary result. Categorical data was analyzed using nonparametric χ² tests. Statistical analyses were conducted utilizing IBM SPSS software, version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States).

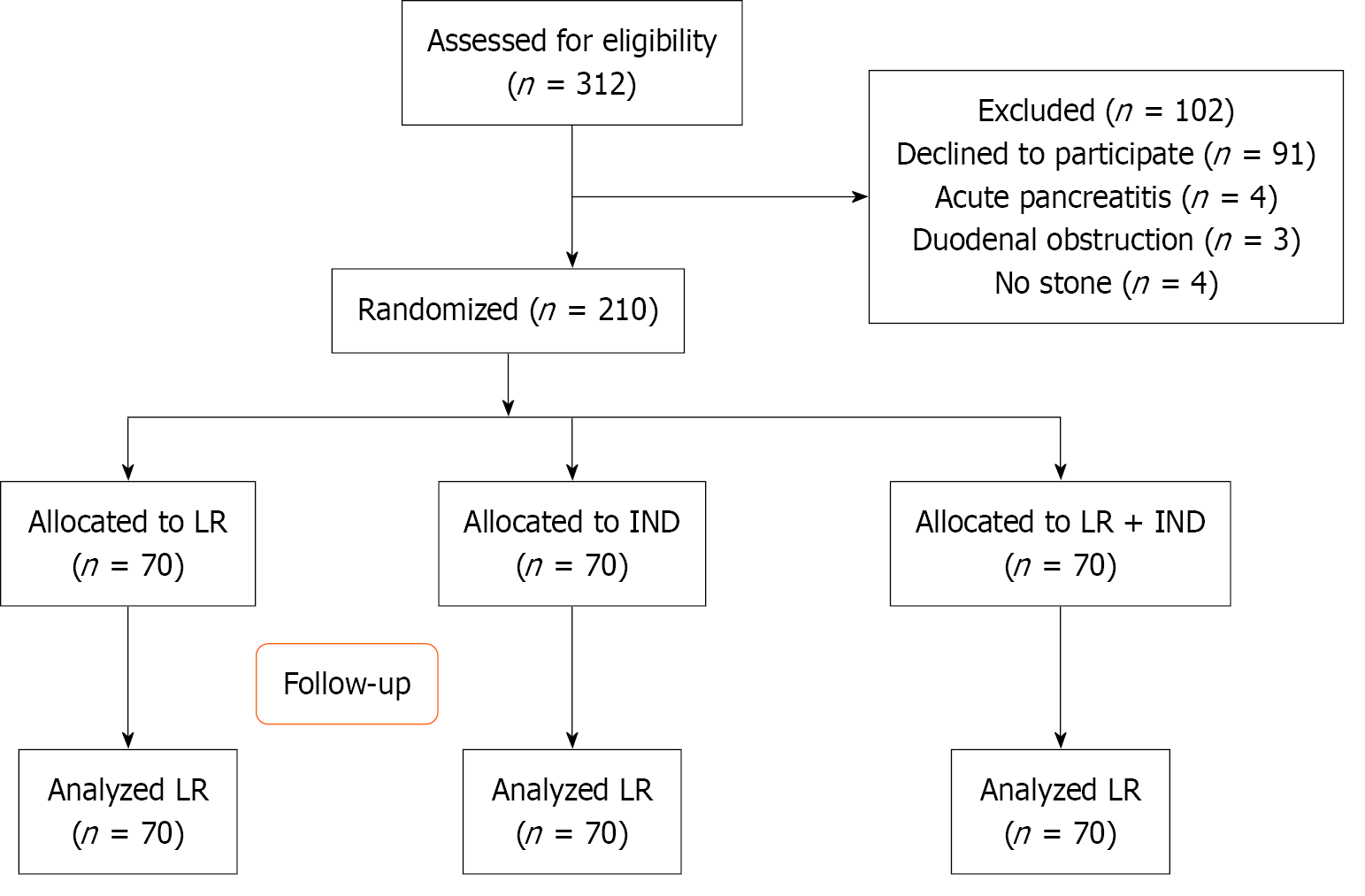

During the trial period, 312 participants were evaluated for screening, with 11 patients eliminated for various reasons: (1) Biliary pancreatitis (n = 4); (2) No stone (n = 5); and (3) Duodenal obstruction (n = 3). After initial exclusion, 91 patients declined to consent for the study. Therefore, 210 patients were randomized to each treatment arm, among these, 70 patients received aggresive intravenous hydration with LR, 70 patients underwent aggressive hydration with LR + IND, and 70 patients received IND alone (Figure 1).

No significant differences were observed in the basic characteristics of patients across the different groups concerning sex, age, comorbidities, indications for therapeutic ERCP, challenging cannulation, precut access, pancreatic stenting insertion, and the number of risk factors for PEP (Table 1). The demographics and risk factors for PEP were consistent across the study groups (Table 1). Fifty-nine percent of patients had multiple significant risk factors for PEP. All patients underwent follow-up assessments at 24 hours and 30 days post-ERCP.

| Characteristics | IND (n = 70) | LR (n = 70) | IND + LR (n = 70) | P value | |

| Mean age (years) | 60 | 63 | 61 | 0.44 | |

| Sex | Female | 39 (55.71) | 34 (48.57) | 38 (57.28) | 0.62 |

| Male | 31 (44.28) | 36 (51.42) | 32 (45.71) | - | |

| Mean risk score (number) | 1.9 | 1.8 | 2 | 0.36 | |

| Female and age < 50 years | 23 (32.85) | 26 (37.14) | 25 (35.71) | 0.12 | |

| Normal total bilirubin (< 1 mg/dL) | 29 (41.42) | 32 (45.71) | 34 (48.57) | 0.09 | |

| History of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis | 5 (7.1) | 7 (1) | 6 (8.5) | 0.23 | |

| History of recurrent pancreatitis | 2 (2.8) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.8) | 0.72 | |

| Difficult cannulation (> 8 attempts) | 11 (15.71) | 14 (20.00) | 16 (22.85) | 0.14 | |

| Biliary sphincterotomy | 52 (74.28) | 46 (65.71) | 49 (70.00) | 0.23 | |

| Precut sphincterotomy | 21 (30) | 17 (24.28) | 16 (22.85) | 0.11 | |

| Plastic biliary stent | 13 (18.57) | 21 (30.00) | 22 (31.42) | 0.09 | |

| Self-expanding metal stent | 2 (2.8) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) | 0.61 | |

| Pancreatography | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | 0.87 | |

| Pancreatic sphincterotomy | 7 (10) | 9 (12.85) | 10 (14.28) | 0.21 | |

| Pancreatic acinarization | 2 (2.8) | 4 (5.71) | 3 (4.28) | 0.31 | |

| Pancreatic duct stent placement | 16 (22.85) | 12 (17.14) | 11 (15.71) | 0.21 | |

Pancreatitis occurred after an ERCP in 23 (10.9%) of 210 patients. The LR group had twelve (17.1%), while the IND group had seven (10%) (Table 2, Figure 2A). The rate of PEP differed significantly between the LR and LR + IND groups (P = 0.04). This result translated into an absolute risk reduction of 14.6%, 95%CI: 0.13-0.15 and a relative risk reduction of 70.0%, 95%CI: 0.68-0.75. The number required to treat was 6.9, 95%CI for LR + IND. No differences were identified among the comparisons of the other experimental groups that were analyzed (Figure 2A).

| Outcomes | IND (n = 70) | LR (n = 70) | IND + LR (n = 70) | P value |

| PEP | 7 (10.00) | 12 (17.14) | 4 (5.71) | 1 |

| Severe PEP | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.8) | 2 (2.8) | 0.86 |

| Pseudocyst | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| Pulmonary edema | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 0.92 |

| Renal failure | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 0.93 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.8) | 0 (0) | 0.82 |

| Anaphylaxis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.98 |

| Death | 2 (2.8) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) | 1.00 |

| Readmission | 5 (7.14) | 7 (10) | 2 (2.8) | 1 |

| Mean length of stay, days | 3.40 | 4.70 | 3.12 | 0.12 |

One case of severe AP occurred in the IND group (1.4%), and two cases of pancreatitis with pseudocyst (localized AE) in the LR group. All six deaths in the research happened in cancer patients who were admitted to hospice services. One death was reported in the LR group, two in the IND group, and one in the LR + IND group. The mean length of stay did not differ across the groups. There was a substantial difference in readmission rates between the LR (13%) vs LR + IND (2%) (P = 0.03). There were no significant differences in readmission rates across the other experimental trial group comparisons (Figure 2B).

There were 5 (3%) AEs. Each trial group included one patient who reported ARF. One patient in both the IND group and LR group experienced this AE regardless not being exposed to NSAIDs. One patient in the IND group developed severe AP accompanied by ARF seven days post-ERCP. There was one case of pulmonary edema in a patient (LR). The patient was subsequently diagnosed with a pulmonary embolism, which may have played a role in her hypoxia. No instances of gastrointestinal bleeding or anaphylaxis associated with NSAIDs were observed (Table 2).

The rate of post-sphincterotomy bleeding was 1.42%. All patients reporting bleeding achieved recovery with endoscopic treatment. Post-ERCP cholangitis was observed in two patients [0.5%: (1) One in the LR group; and (2) One in the IND group; P = 0.81]. No cases of perforation occurred during the trial.

In the current prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial in a population of high-risk patients performing ERCP, there is a reduced incidence of PEP in those who underwent combination therapy with LR + IND compared to those treated with LR or IND alone.

The pathophysiological process of AP states that microcirculation declines during the initial phase, leading to pancreatic necrosis and multiorgan failure[32,33]. As a result, maintaining enough arterial pressure should help prevent AP and multiorgan failure. Regardless numerous fluid solutions, such as LR and NSS, have been employed with varying fluid volumes required to sustain arterial pressure[24,25], there is currently absence of approval regarding the appro

The 2012 International Association of Pancreaticologists/the American Pancreatic Association guidelines suggest for targeted IVF administration at a rate of 5-10 mL/kg/hour for the initial treatment of AP[34]. Nevertheless, intensive intravenous hydration (more than 10 mL/kg/hour) may adversely affect the prognosis of patients with severe AP[23,24]. If the bolus volume was included in the current study, the aggregate volume (considering 30 minutes for the ERCP and 30 minutes for bolus adminisration) was around 5.0 mL/kg/hour for 9 hours. As a result, the fluid administration in the aggressive LR group was adequate for the early treatment of AP.

Systemic inflammation is one of the most essential pathological characteristics of AP[35]. Compared to NSS, LR provides numerous anti-inflammatory advantages. A recent randomized study comparing LR with NSS found that LR reduces the rate of SIRS[24]. Furthermore, LR had a lower rate of metabolic acidosis than NSS[26,27]. These data prove that extensive fluid therapy with LR would be recognized as the conventional IVF administration approch for preventing PEP in high-risk individuals.

Readmission rates were reduced among patients who received LR + IND compared to the LR group. The LR + IND method revealed an number required to treat of 6.9 for preventing one episode of PEP. In an era of rising healthcare expenses, quality metrics, and prompt patient care, admitting every ERCP patient requiring an 8-hour infusion of LR is quite difficult. In general, we intended to assess the capacity of a quick IVF administration in association with IND to avoid PEP. The combo treatment also revealed decreases in 30-day readmission rates. We believe that applying a more feasible association of prevention interventions in individuals at high risk for PEP proved to be more advantageous than unique method strategy.

Due to Buxbaum et al's study[25] assessed risk factors that enhance the pre-test incidence of PEP, early detection of patients and the introduction of preventive interventions have become crucial for preventing this complications. In this investigation, all patients were considered high-risk. Previous researchs analyzing this cohort with various high-risk factors found PEP incidences ranging betwin 13% and 30%[21,25,26]. The selection of only this group of patients may explain the high incidence of PEP (15%) in the study groups, which is consistent with previous trials that used prophylactic PD stent insertion[12].

When analyzing preventative methods for ductal pressure balance, our cohort showed similar rates of PD inquiry and eventual stent installation throughout all research groups. The identical rates of preventive PD stent installation likely increased homogeneity across the research groups, facilitating a greater meaningful evaluation of our treatment interventions[11,12]. Six prospective studies have tested subsequent suppression of the inflammatory process, using rectal IND, demonstrating much decreased comparative rates of PEP to placebo[31,36-40].

In this trial, we found an increase toward lower PEP in the IND-alone arm (10% vs 17% LR). However, this difference was not significant, likely due to the limited sample size of this investigation. Though there was a bias toward a difference between both groups, we recognize that this finding contradicts previous evidence[36] on the administration of IND as a standalone treatment for high-risk patients[31,37-40]. It is essential to emphasize that this comparative study was conducted as an investigative measure, and no statistical power was created for this specific comparison. Con

Mok et al's study[21] examined LR + placebo and LR + IND compared with NSS. There was no difference in the rates of PEP. The incidence of PEP was lower in LR + IND group compared to others. In our trial, the combination LR + IND reduce the rate of PEP comared to LR or IND alone. Furthermore, We opted to assess a more realistic, 1 L LR infusion, generally given within 30 minutes.

When we compared the LR group (LR alone) to the IND group, there was no difference in PEP rates (10% vs 17%, P = 0.05). Though counterintuitive to previous studies of LR for preventing PEP, it proved challenging to draw a clear. The conclusion drawn from this comparison is limited due to the trial's lack of specified design for this purpose. Again, the result suggests a possible interaction between IND and LR that could help prevent PEP. Overall, participants acknowledged the medicines used in this study, and the incidence of side events was similar across the groups. Furthermore, considering the clinical circumstances surrounding each AE, it is unlikely that research participation caused them. There were no reports of allergy or gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Patients who were at high risk for volume overload were excluded; thus, our findings cannot be extended to these populations. This study's strengths included strict inclusion criteria for high-risk individuals and complete follow-up data collection. Recent trials, which found no decrease in the rate of PEP with IND, included individuals at average risk for PEP[42]. Aside from the inclusion criterion, our randomization and double-blinding technique are likely to have considerably reduced any potential bias in this trial. There are several limitations to the present study. First, this study covers our sample size. This study was designed to discover a statistically significant difference between LR + IND and LR or IND alone in high-risk patients.

Second, inflammatory cytokines were not assessed. Had we performed this, we would have gained a comprehensive understanding of the anti-inflammatory mechanisms of LR. Third, the duration of the ERCP procedure was not documented in this trial. Because the time of each procedure varies, the total volume perfused may differ, resulting in differences in efficacy and adverse effects.

Fourth, in the present study, pancreatic stents were placed in patients who had easy access to the PD following a transpancreatic sphincterotomy. Preventive pancreatic stent insertion is strongly advised to prevent PEP in high-risk patients; nevertheless, adverse outcomes associated with such attempts include PEP, stent-induced pancreatic ductal injury, and inward migration[14]. Finally, this experiment is a single-center study.

The current randomized, double-blind, controlled study shows that LR infusion combined with rectal IND may decrease the occurrence of PEP and post-procedure readmission compared with LR or IND alone in high-risk patients.

| 1. | Kochar B, Akshintala VS, Afghani E, Elmunzer BJ, Kim KJ, Lennon AM, Khashab MA, Kalloo AN, Singh VK. Incidence, severity, and mortality of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a systematic review by using randomized, controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:143-149.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 32.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Akshintala VS, Kanthasamy K, Bhullar FA, Sperna Weiland CJ, Kamal A, Kochar B, Gurakar M, Ngamruengphong S, Kumbhari V, Brewer-Gutierrez OI, Kalloo AN, Khashab MA, van Geenen EM, Singh VK. Incidence, severity, and mortality of post-ERCP pancreatitis: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of 145 randomized controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;98:1-6.e12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Mazaki T, Masuda H, Takayama T. Prophylactic pancreatic stent placement and post-ERCP pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2010;42:842-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Freeman ML. Pancreatic stents for prevention of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1354-1365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Inamdar S, Han D, Passi M, Sejpal DV, Trindade AJ. Rectal indomethacin is protective against post-ERCP pancreatitis in high-risk patients but not average-risk patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:67-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Shi N, Deng L, Altaf K, Huang W, Xue P, Xia Q. Rectal indomethacin for the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2015;26:236-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Puig I, Calvet X, Baylina M, Isava Á, Sort P, Llaó J, Porta F, Vida F. How and when should NSAIDs be used for preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li X, Tao LP, Wang CH. Effectiveness of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:12322-12329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gross V, Leser HG, Heinisch A, Schölmerich J. Inflammatory mediators and cytokines--new aspects of the pathophysiology and assessment of severity of acute pancreatitis? Hepatogastroenterology. 1993;40:522-530. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Mäkelä A, Kuusi T, Schröder T. Inhibition of serum phospholipase-A2 in acute pancreatitis by pharmacological agents in vitro. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1997;57:401-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Choudhary A, Bechtold ML, Arif M, Szary NM, Puli SR, Othman MO, Pais WP, Antillon MR, Roy PK. Pancreatic stents for prophylaxis against post-ERCP pancreatitis: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:275-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Mazaki T, Mado K, Masuda H, Shiono M. Prophylactic pancreatic stent placement and post-ERCP pancreatitis: an updated meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:343-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Sherman S, Blaut U, Watkins JL, Barnett J, Freeman M, Geenen J, Ryan M, Parker H, Frakes JT, Fogel EL, Silverman WB, Dua KS, Aliperti G, Yakshe P, Uzer M, Jones W, Goff J, Earle D, Temkit M, Lehman GA. Does prophylactic administration of corticosteroid reduce the risk and severity of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a randomized, prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:23-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zheng M, Bai J, Yuan B, Lin F, You J, Lu M, Gong Y, Chen Y. Meta-analysis of prophylactic corticosteroid use in post-ERCP pancreatitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Knoefel WT, Kollias N, Warshaw AL, Waldner H, Nishioka NS, Rattner DW. Pancreatic microcirculatory changes in experimental pancreatitis of graded severity in the rat. Surgery. 1994;116:904-913. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Pandol SJ, Saluja AK, Imrie CW, Banks PA. Acute pancreatitis: bench to the bedside. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1127-1151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 433] [Cited by in RCA: 464] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Strate T, Mann O, Kleinhans H, Rusani S, Schneider C, Yekebas E, Freitag M, Standl T, Bloechle C, Izbicki JR. Microcirculatory function and tissue damage is improved after therapeutic injection of bovine hemoglobin in severe acute rodent pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2005;30:254-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wu D, Wan J, Xia L, Chen J, Zhu Y, Lu N. The Efficiency of Aggressive Hydration With Lactated Ringer Solution for the Prevention of Post-ERCP Pancreatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:e68-e76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhang ZF, Duan ZJ, Wang LX, Zhao G, Deng WG. Aggressive Hydration With Lactated Ringer Solution in Prevention of Postendoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Pancreatitis: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:e17-e26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hosseini M, Shalchiantabrizi P, Yektaroudy K, Dadgarmoghaddam M, Salari M. Prophylactic Effect of Rectal Indomethacin Administration, with and without Intravenous Hydration, on Development of Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Pancreatitis Episodes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Arch Iran Med. 2016;19:538-543. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Mok SRS, Ho HC, Shah P, Patel M, Gaughan JP, Elfant AB. Lactated Ringer's solution in combination with rectal indomethacin for prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis and readmission: a prospective randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:1005-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Working Party of the British Society of Gastroenterology; Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland; Pancreatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland; Association of Upper GI Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland. UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2005;54 Suppl 3:iii1-iii9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 337] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Banks PA, Freeman ML; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2379-2400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1181] [Cited by in RCA: 1177] [Article Influence: 58.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wu BU, Hwang JQ, Gardner TH, Repas K, Delee R, Yu S, Smith B, Banks PA, Conwell DL. Lactated Ringer's solution reduces systemic inflammation compared with saline in patients with acute pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:710-717.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 328] [Cited by in RCA: 350] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Buxbaum J, Yan A, Yeh K, Lane C, Nguyen N, Laine L. Aggressive hydration with lactated Ringer's solution reduces pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:303-7.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ, Lande JD, Pheley AM. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1703] [Article Influence: 56.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 27. | Freeman ML, DiSario JA, Nelson DB, Fennerty MB, Lee JG, Bjorkman DJ, Overby CS, Aas J, Ryan ME, Bochna GS, Shaw MJ, Snady HW, Erickson RV, Moore JP, Roel JP. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:425-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 801] [Cited by in RCA: 852] [Article Influence: 34.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1890] [Cited by in RCA: 2086] [Article Influence: 59.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 29. | Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J, Vege SS; American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1400-15; 1416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1232] [Cited by in RCA: 1428] [Article Influence: 109.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 30. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4719] [Article Influence: 363.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (48)] |

| 31. | Elmunzer BJ, Scheiman JM, Lehman GA, Chak A, Mosler P, Higgins PD, Hayward RA, Romagnuolo J, Elta GH, Sherman S, Waljee AK, Repaka A, Atkinson MR, Cote GA, Kwon RS, McHenry L, Piraka CR, Wamsteker EJ, Watkins JL, Korsnes SJ, Schmidt SE, Turner SM, Nicholson S, Fogel EL; U. S. Cooperative for Outcomes Research in Endoscopy (USCORE). A randomized trial of rectal indomethacin to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1414-1422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 478] [Cited by in RCA: 531] [Article Influence: 37.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Kusterer K, Enghofer M, Zendler S, Blöchle C, Usadel KH. Microcirculatory changes in sodium taurocholate-induced pancreatitis in rats. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:G346-G351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Muddana V, Whitcomb DC, Khalid A, Slivka A, Papachristou GI. Elevated serum creatinine as a marker of pancreatic necrosis in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:164-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2013;13:e1-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1080] [Cited by in RCA: 1095] [Article Influence: 84.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (10)] |

| 35. | Minkov GA, Halacheva KS, Yovtchev YP, Gulubova MV. Pathophysiological mechanisms of acute pancreatitis define inflammatory markers of clinical prognosis. Pancreas. 2015;44:713-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Döbrönte Z, Szepes Z, Izbéki F, Gervain J, Lakatos L, Pécsi G, Ihász M, Lakner L, Toldy E, Czakó L. Is rectal indomethacin effective in preventing of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10151-10157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Montaño Loza A, García Correa J, González Ojeda A, Fuentes Orozco C, Dávalos Cobián C, Rodríguez Lomelí X. [Prevention of hyperamilasemia and pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with rectal administration of indomethacin]. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2006;71:262-268. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Montaño Loza A, Rodríguez Lomelí X, García Correa JE, Dávalos Cobián C, Cervantes Guevara G, Medrano Muñoz F, Fuentes Orozco C, González Ojeda A. [Effect of the administration of rectal indomethacin on amylase serum levels after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, and its impact on the development of secondary pancreatitis episodes]. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2007;99:330-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Sotoudehmanesh R, Khatibian M, Kolahdoozan S, Ainechi S, Malboosbaf R, Nouraie M. Indomethacin may reduce the incidence and severity of acute pancreatitis after ERCP. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:978-983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 40. | Döbrönte Z, Toldy E, Márk L, Sarang K, Lakner L. [Effects of rectal indomethacin in the prevention of post-ERCP acute pancreatitis]. Orv Hetil. 2012;153:990-996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Rinderknecht H. Activation of pancreatic zymogens. Normal activation, premature intrapancreatic activation, protective mechanisms against inappropriate activation. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31:314-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Levenick JM, Gordon SR, Fadden LL, Levy LC, Rockacy MJ, Hyder SM, Lacy BE, Bensen SP, Parr DD, Gardner TB. Rectal Indomethacin Does Not Prevent Post-ERCP Pancreatitis in Consecutive Patients. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:911-7; quiz e19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/