Published online Jan 16, 2026. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v18.i1.113133

Revised: September 17, 2025

Accepted: December 3, 2025

Published online: January 16, 2026

Processing time: 152 Days and 18.9 Hours

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is a pioneering medical technique de

Core Tip: Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has evolved from an ancient remedy into a scientifically validated, high-efficacy treatment for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection, with growing potential for managing other diseases linked to gut dysbiosis. This article explores FMT’s historical origins, mechanisms of action, clinical applications, safety concerns, and regulatory challenges. It emphasizes the need for standardized protocols, rigorous donor screening, and long-term monitoring to ensure safe and effective clinical integration. As microbiome science advances, FMT stands at the frontier of personalized, microbiota-based therapeutics.

- Citation: Uppala PK, Karanam SK, Maddi R. Science of fecal microbiota transplant: From history to cutting-edge clinical practice. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2026; 18(1): 113133

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v18/i1/113133.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v18.i1.113133

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has transitioned from early medical traditions into a contemporary therapy mainly aimed at rebalancing the gut microbiome. The process entails the transfer of carefully prepared stool from a thoroughly evaluated healthy donor into the digestive system of a patient. Although FMT was first used for recurrent Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) infections (rCDI), its use is now being investigated for a wider array of intestinal and systemic disorders linked to microbial irregularities, known as dysbiosis[1].

Scientific research currently highlights FMT’s effectiveness in treating rCDI, with outcomes that often surpass those achieved by standard antibiotic regimens. Nevertheless, expanding its use to other health issues requires well-defined protocols for choosing donors, preparing stool samples, selecting delivery methods, and monitoring patients over time[2]. This article thoroughly examines the historical background, approved medical uses, safety measures, and recent advancements in the field of FMT. At its core, FMT seeks to rebalance and enrich the diversity of the gut microbiota, wh

As a notable progression in microbiome-targeted medicine, FMT aims to reintroduce microbial variety and restore normal gut function, thereby promoting a healthier internal environment for the recipient. Its origins date back to ancient China in the 4th century, where fecal preparations were utilized to address severe diarrhea and foodborne illnesses[3]. Modern clinical interest in FMT was renewed in the mid-1900s following reports of its effectiveness against pseudomembranous colitis. Since the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s 2013 endorsement for rCDI treatment, FMT has become a recognized alternative, especially when standard antibiotic therapies are ineffective[4].

In addition to rCDI, FMT is being actively studied for its possible benefits in various gastrointestinal conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), as well as for non-intestinal issues like obesity, liver-related brain disorders, autoimmune diseases, and some neuropsychiatric conditions. Despite these promising avenues, FMT continues to be considered experimental in many areas due to ongoing concerns regarding safety, regu

This article presents a detailed exploration of FMT, addressing its historical roots, underlying mechanisms, current clinical uses, evolving methodologies, safety issues, and regulatory obstacles. The intention is to deliver a holistic per

| Aspect | Details |

| Definition | A medical procedure in which stool from a healthy donor is transferred into the gastrointestinal tract of a patient to restore healthy gut microbiota |

| Purpose | To re-establish a balanced intestinal microbiome, especially in cases of recurrent CDI |

| Indications | Recurrent or refractory CDI |

| Investigational use in IBD, IBS, metabolic syndrome, and other microbiome-related disorders | |

| Procedure methods | Colonoscopy |

| Nasoduodenal/nasojejunal tube | |

| Enema | |

| Oral capsules (freeze-dried stool) | |

| Donor selection | Healthy individuals screened for infectious diseases, gastrointestinal disorders, metabolic and autoimmune diseases |

| Mechanism of action | Introduces diverse, beneficial bacteria to outcompete pathogenic organisms, modulate immune function, and improve gut barrier function |

| Advantages | High cure rate for recurrent CDI (over 85%) |

| Minimally invasive (in capsule form) | |

| Restores gut microbial diversity quickly | |

| Risks and limitations | Risk of transmitting infections |

| Unknown long-term microbiome changes | |

| Potential for metabolic or immune effects | |

| Regulatory restrictions in some countries | |

| Recent developments | Standardized, frozen microbiota preparations |

| Synthetic microbiota capsules | |

| Ongoing research into personalized microbiome therapy |

C. difficile infection (CDI) encompasses a wide range of clinical presentations, from mild diarrhea to serious, potentially fatal colitis. Precise categorization is vital for directing appropriate treatment plans, including decisions about when and how to use FMT[6-8].

rCDI describes the reappearance of symptoms within two months after an initial episode has resolved, usually caused by either reinfection or a relapse with the same or a different strain of C. difficile. Refractory CDI refers to cases where symptoms persist despite standard antibiotic therapy and may be worsened by systemic infection or compromised immune function. Severe CDI is identified by clinical indicators such as a white blood cell count above 15000 cells per milliliter and/or a serum creatinine level of at least 1.5 mg/dL, often in conjunction with fever and signs of organ impairment. Fulminant CDI is the most extreme and dangerous form, marked by complications like low blood pressure, septic shock, toxic megacolon, intestinal perforation, or elevated serum lactate, all of which are linked to high rates of illness and death. These classifications are essential for deciding the urgency and approach to FMT, especially in severe or fulminant cases where prompt intervention can be crucial for saving lives.

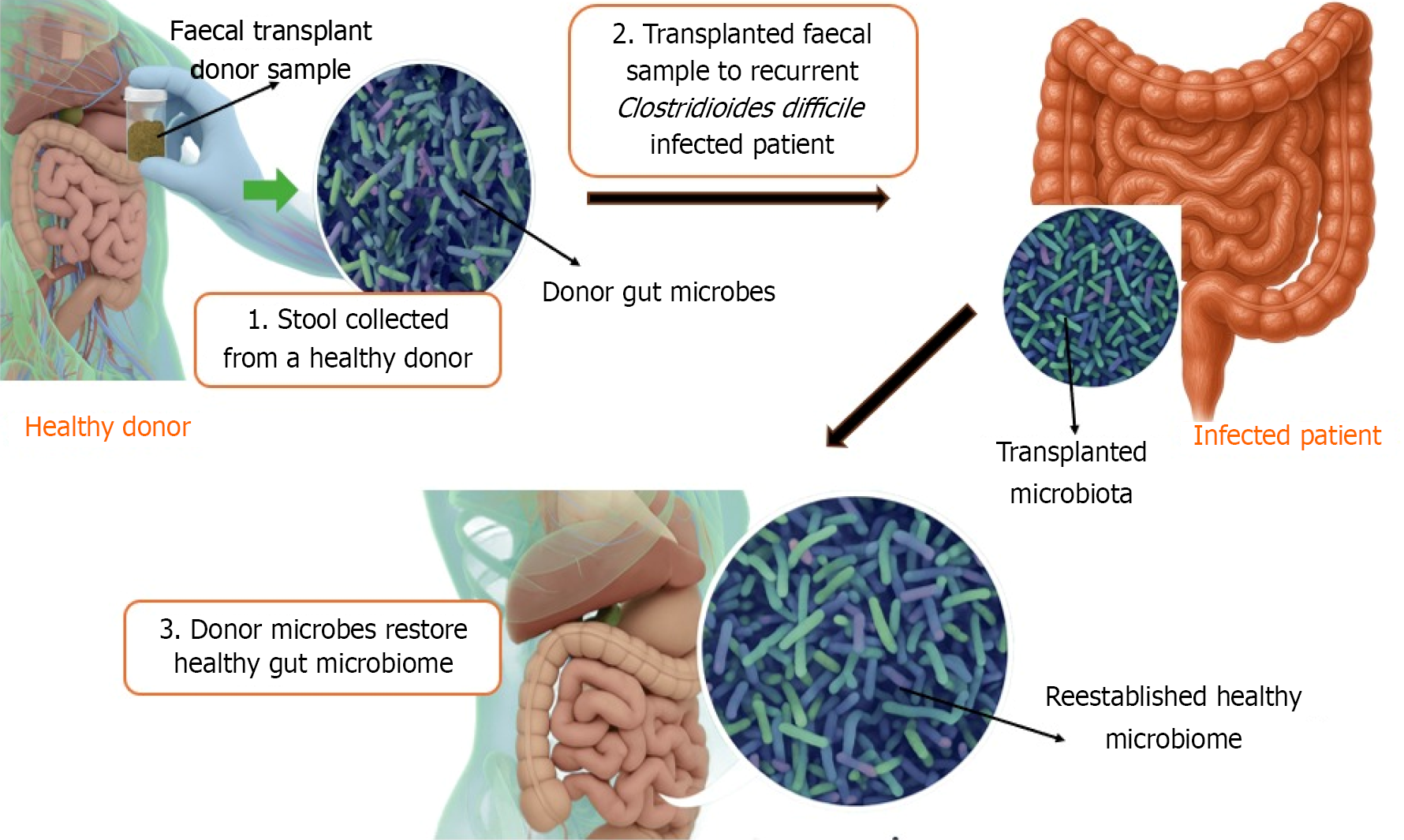

FMT involves the transfer of processed fecal material from a healthy donor into the gastrointestinal tract of a recipient to restore a balanced gut microbiome. Originally developed to manage rCDI, FMT has evolved as a potential treatment for various gastrointestinal and metabolic disorders.

The human gut microbiota plays a vital role in immune modulation, nutrient metabolism, and resistance against pa

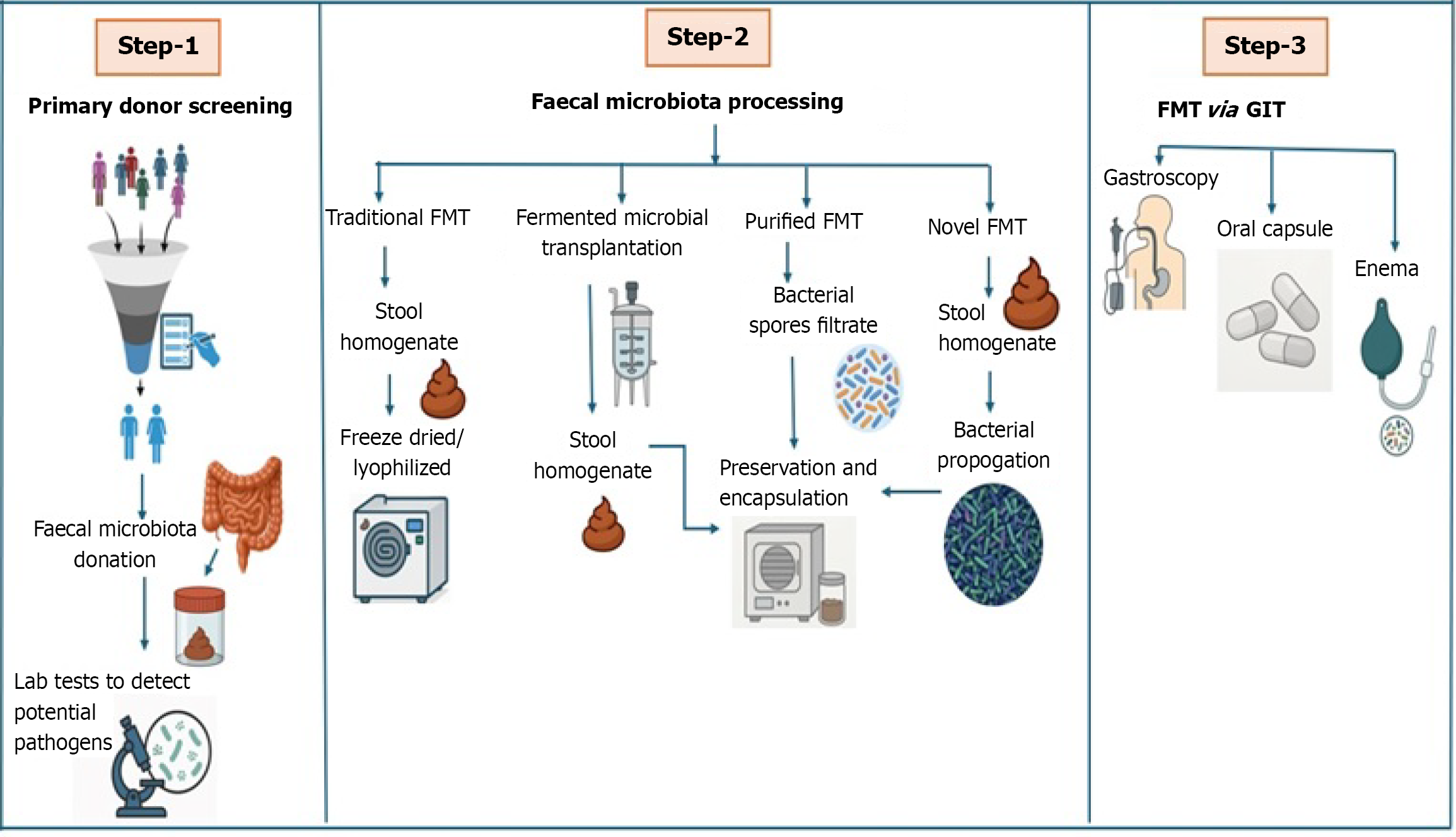

Donor selection is a critical step to ensure the safety and efficacy of FMT. Healthy individuals undergo rigorous screening for infectious diseases, gastrointestinal disorders, antibiotic usage, and lifestyle factors. Once selected, fecal samples are collected, homogenized into a slurry, and filtered to remove undigested material. Depending on the storage strategy, cryopreservatives like trehalose, maltodextrin may be added to facilitate freezing.

FMT can be administered through multiple routes based on clinical need and feasibility: (1) Colonoscopy and rectal enema: Provide direct delivery to the colon and are preferred in rCDI cases; (2) Oral capsules: Offer a non-invasive, patient-friendly method using encapsulated lyophilized fecal material; and (3) Nasogastric (NG) or nasojejunal tubes: Deliver material to the upper gastrointestinal tract but may carry a risk of aspiration.

Each route has distinct advantages and limitations, and choice depends on the patient’s condition, tolerance, and therapeutic goal. FMT, sometimes referred to as stool transplant or bacteriotherapy, is a medical intervention developed to re-establish a balanced and diverse community of gut microbes in individuals whose intestinal flora has been disrupted[9]. By transferring processed stool from a carefully screened donor into the gastrointestinal tract of a recipient improves gut microbiome of diseased patient. This involves transferring specially prepared fecal matter from a rigorously tested, healthy donor to a recipient affected by conditions marked by microbial imbalance within the gut[10,11]. The main approved use of FMT is for managing recurrent or refractory rCDI, especially when repeated courses of antibiotics have proven ineffective or led to repeated episodes of infection[12,13]. FMT is supported by its proven ability to rebalance the gut microbial community, which is often disrupted by antibiotics, chronic illness, or other external influences.

FMT can be delivered in several ways, including via colonoscopy, upper endoscopy, tubes inserted through the nose into the stomach or small intestine (NG or nasoduodenal tubes), enema, or through the use of oral capsules[14]. Colonoscopic administration is currently the most common and well-researched method distributing the microbial material throughout the colon, while capsule-based FMT provides a less invasive alternative that enhances patient comfort and adherence. Before use, each donor sample undergoes extensive screening to detect any harmful bacteria, viruses, or parasites, thereby prioritizing patient safety[15].

Donor selection is a cornerstone of FMT safety and success. Potential donors must undergo thorough health screenings, including detailed interviews, blood tests, and stool analyses, to rule out infectious agents and chronic conditions. Only those who meet strict eligibility criteria are selected, and the donated stool is prepared either as a liquid suspension or in encapsulated form to maintain the viability of the microbial communities[16].

A typical FMT procedure involves three main steps: (1) Fecal collection: Stool is obtained from a healthy, thoroughly screened donor; (2) Specimen preparation: The fecal material is processed to isolate and preserve beneficial microorganisms; and (3) Transplantation: The prepared microbiota is introduced into the patient’s gastrointestinal tract via the chosen administration route.

Despite its demonstrated effectiveness, FMT protocols for donor selection, stool preparation, and administration are not yet standardized across all institutions. Ongoing research is focused on refining these processes to further enhance both the safety and efficacy of FMT in clinical practice[17].

FMT has undergone significant evolution in its administration methods since its earliest uses in the 1950s. Initially, retention enemas were the mainstay for delivering fecal material, particularly for managing antibiotic-associated colitis. As the procedure has advanced, a variety of alternative techniques have emerged, including NG and nasoduodenal tube infusions, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, colonoscopy, and, more recently, orally ingested capsules[18-20].

Colonoscopy stands as the most extensively studied and commonly utilized route for FMT. This method allows precise and widespread distribution of donor fecal material throughout the colon, making it especially effective for treating rCDI. Upper gastrointestinal routes, such as nasoduodenal tube or gastroscope delivery, offer an alternative but may present a higher risk of aspiration. Capsule-based FMT is increasingly favored for its convenience, minimal invasiveness, and reduced risk of procedural complications (Figure 1).

The advent of cryopreserved stool preparations has revolutionized the practical aspects of FMT. By freezing, filtering, and carefully processing donor material, clinicians can create stool banks that improve accessibility and streamline the integration of FMT into routine clinical care. This advancement not only enhances safety and standardization but also supports broader implementation of FMT across diverse healthcare settings.

Donor selection remains a cornerstone of FMT safety and effectiveness. Prospective donors undergo thorough health evaluations, including detailed interviews, blood tests, and stool analyses, to rule out infections and chronic diseases. Only those who meet stringent health criteria are selected, and the donated stool is processed into liquid suspensions or capsules to preserve live microbial communities for transplantation.

Ultimately, the choice of FMT administration route should be individualized, taking into account the patient’s clinical status, preferences, and overall tolerance for the procedure. As FMT continues to evolve, ongoing research and inno

The choice of FMT administration route is not merely procedural; it significantly affects the localization, colonization efficiency, and persistence of transplanted microbial communities. For instance, colonoscopic or rectal delivery ensures direct inoculation into the distal colon, where C. difficile typically exerts its pathogenic effects. In contrast, oral capsule delivery must overcome upper gastrointestinal barriers such as gastric acidity and bile salts, potentially affecting microbial viability and engraftment. These variations can influence the speed and extent to which dysbiosis is corrected and a balanced microbial ecosystem is restored. Therefore, understanding the relationship between administration routes and microbiota engraftment is critical to interpreting FMT efficacy in various clinical contexts.

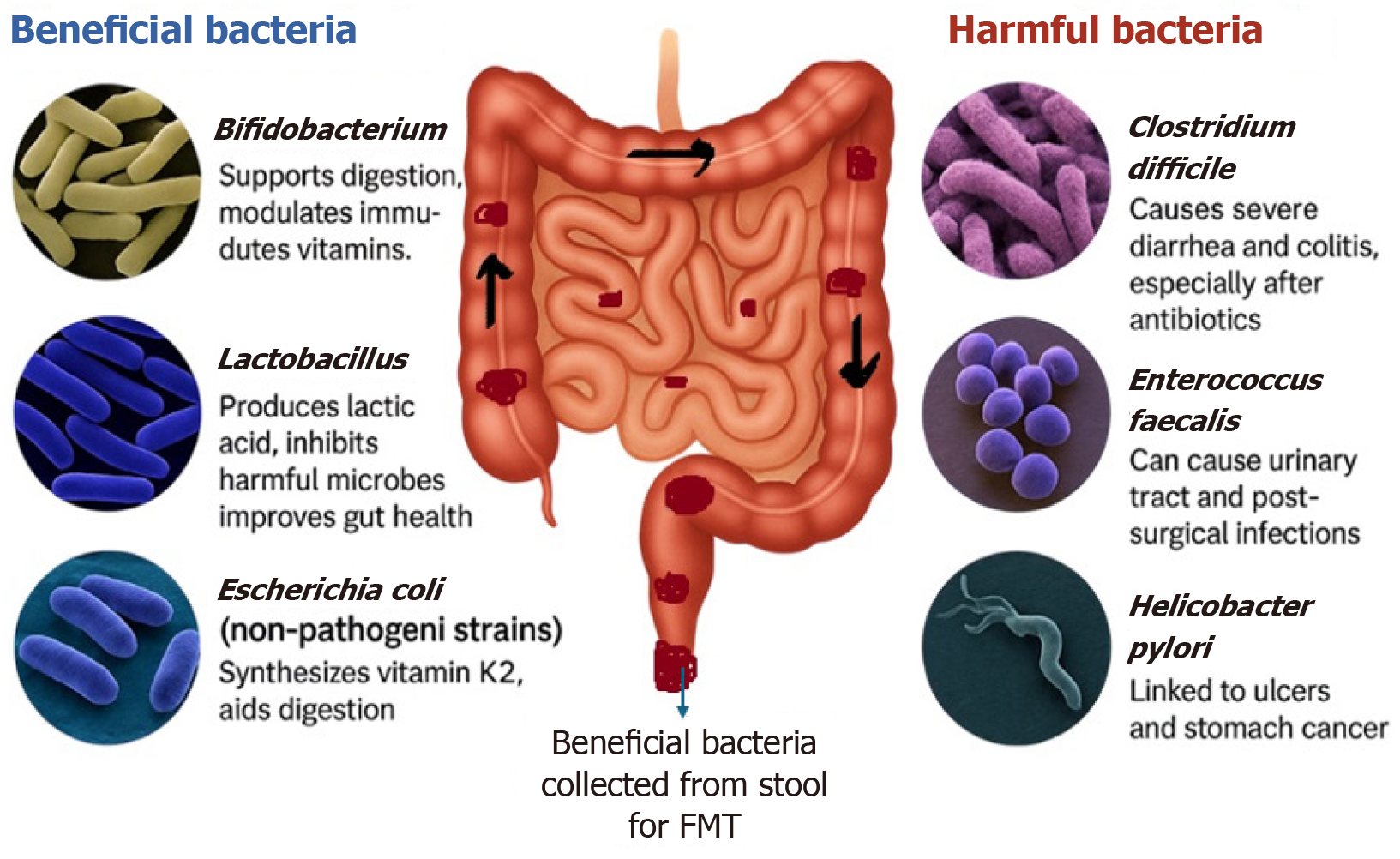

The human gastrointestinal tract harbors trillions of microorganisms, collectively referred to as the gut microbiota. This ecosystem is composed of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and archaea, with bacterial species being the most predominant. The dominant bacterial phyla - Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria - play crucial roles in digestion, immune regulation, and metabolic processes (Figure 2)[21-23].

Disruption of the balance among these microbial populations, a state known as dysbiosis, can compromise gut barrier integrity, decrease resistance to pathogens, and impair immune modulation. Dysbiosis is now recognized as a con

FMT has demonstrated efficacy in reversing dysbiosis by reintroducing a complex and stable microbial community. Unlike probiotics, which typically introduce a limited number of strains and often fail to achieve long-term colonization, FMT provides a more comprehensive and lasting restoration of the gut microbiome. This distinction positions FMT as a potentially superior therapeutic approach in cases where microbial imbalance underpins disease pathology[21-23].

The therapeutic effectiveness of FMT is rooted in its capacity to restore a rich and balanced microbial community within the recipient’s gut. This renewed ecosystem exerts competitive pressure against pathogens such as C. difficile, hindering their ability to colonize and produce toxins. The success of FMT in rCDI has prompted deeper exploration of its microbiological and metabolic underpinnings[24-26].

A central mechanism involves the modulation of bile acid metabolism. In a healthy gut, specific bacteria convert primary bile acids into secondary bile acids, which suppress the germination and growth of C. difficile spores. Patients with recurrent C. difficile infection often exhibit diminished levels of these protective secondary bile acids; FMT reintroduces microbial populations capable of this conversion, thereby rebalancing the gut environment.

Another key process is the regulation of sialic acid metabolism. Antibiotic-induced dysbiosis can lead to increased free sialic acid in the gut, which serves as a nutrient source for C. difficile. FMT may restore microbial species that compete for this resource, reducing the availability for pathogenic growth.

Short-chain fatty acids, particularly butyrate, are also crucial. These compounds - produced by microbial fermentation - support colonic epithelial health, modulate immune function, and help reduce inflammation. FMT has been shown to increase the abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria, which may contribute to symptom improvement in both rCDI and other gastrointestinal disorders.

The strongest clinical evidence for FMT is in the treatment of rCDI. Multiple randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews consistently report cure rates between 85% and 90% following a single infusion, surpassing the effectiveness of standard antibiotic therapy, especially in cases of recurrent or refractory infection (Figure 3)[27].

Since gaining FDA approval for rCDI in 2013, FMT has been investigated for a variety of other indications. IBD, including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, has been a major focus. While outcomes are variable, some studies demonstrate improved remission rates and reduced inflammation, particularly in mild to moderate cases.

FMT is also being studied for its potential in IBS, hepatic encephalopathy, metabolic syndrome, and certain psychiatric and neurological disorders. Preliminary data suggest that FMT may influence host metabolism, immune regulation, and even neurochemical signaling via the gut-brain axis. However, these broader applications remain investigational, and ongoing trials are necessary to identify optimal patient populations, delivery methods, and long-term outcomes before wider clinical adoption is possible.

FMT is generally well-tolerated, but it is not without risk. Most adverse events (AEs) are mild and self-limiting, com

Upper gastrointestinal delivery methods, such as nasoduodenal or NG tube placement, carry risks like aspiration pneumonia. Lower gastrointestinal approaches, including colonoscopy or enema, may result in complications such as intestinal perforation, bleeding, or adverse reactions to sedation. In rare instances, systemic infections such as sepsis have occurred, typically linked to undetected pathogens in donor stool.

Minimizing these risks requires rigorous donor screening protocols. Comprehensive evaluations include testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis viruses, syphilis, and other communicable diseases, as well as screening for gastrointestinal pathogens, parasites, and bacterial toxins. Donors must also be free from autoimmune, metabolic, or malignant diseases and should avoid medications that could alter the gut microbiota. Updated guidelines from health authorities recommend additional screening for emerging pathogens, such as severe acute respiratory distress syndrome corona virus-2 and monkeypox virus, to further enhance patient safety and support the broader implementation of FMT in clinical practice.

FMT is widely recognized as a safe and effective treatment for rCDI, yet it carries certain risks[29]. AEs related to FMT can range from mild, short-lived gastrointestinal symptoms to rare but serious complications. Understanding and systematically documenting these events are vital for optimizing patient safety and supporting informed clinical decisions.

Most adverse effects following FMT are mild and resolve spontaneously within a few days. The most frequently reported symptoms include: Abdominal cramping or discomfort; bloating and excessive gas (flatulence); diarrhea or, less com

Although serious complications are uncommon, they can occur and are often associated with the method of administration or inadequate donor screening: Aspiration pneumonia (primarily with NG or nasoduodenal delivery); Peritonitis (notably in patients on peritoneal dialysis); sepsis or systemic infection (typically due to undetected pathogens in donor stool); toxic megacolon or bowel perforation (more likely following colonoscopic infusion); flare of pre-existing IBD, possibly related to immune activation; and pneumonia or respiratory compromise (more common with upper gastroin

Systematic reviews indicate that the overall incidence of serious AEs is low, with an approximate rate of 3.2% for significant complications, while procedure-related mortality is extremely rare. Notably, the risk of AEs is higher with upper gastrointestinal administration compared to lower gastrointestinal routes such as colonoscopy or enema.

Serious AEs following FMT are relatively rare but must be evaluated in the context of both the route of administration and patient immune status. The overall incidence of serious AEs has been reported to be approximately 3.2%, but this risk is not uniform across all subgroups.

For instance, aspiration pneumonia has been primarily associated with upper gastrointestinal delivery routes such as NG or nasojejunal tubes, especially in elderly or neurologically impaired patients. In contrast, colonoscopic administration may carry a higher risk of intestinal perforation, particularly in individuals with pre-existing colonic inflammation or diverticulosis.

Additionally, immunocompromised patients, including those undergoing chemotherapy, transplant recipients, or individuals with HIV/acquired immuno deficiency syndrome, exhibit an elevated risk for systemic infections, including bacteremia and fungemia, due to reduced mucosal immune surveillance. Reports from the FDA and clinical trials have highlighted isolated but serious infections caused by multi-drug resistant organisms in such patients.

Therefore, careful consideration of FMT route selection and recipient immunological profile is critical to risk miti

Comprehensive long-term safety data regarding FMT are still under development, and definitive conclusions have not yet been established[31]. Based on isolated case reports and theoretical considerations, possible long-term risks include: (1) Transmission of latent infectious agents (such as hepatitis viruses or HIV); (2) Metabolic changes (like weight gain or insulin resistance); (3) Autoimmune responses (including rheumatoid arthritis or thrombocytopenic purpura); and (4) Neurological conditions (such as peripheral neuropathy).

While observational studies generally support the safety of FMT over extended periods, the possibility of late-onset or previously unrecognized complications cannot be entirely excluded.

To minimize risks, all patients considering FMT should receive detailed pre-procedural counseling and must provide informed consent. Essential safety measures include rigorous donor screening, aseptic preparation of fecal material, and careful selection of the most appropriate delivery route. These steps are crucial for reducing the likelihood of AEs and ensuring patient well-being.

While FMT has demonstrated remarkable short-term efficacy in resolving recurrent C. difficile infection, concerns regarding its long-term safety have prompted extended surveillance studies. Initial safety data primarily came from isolated case reports linking FMT to potential complications such as weight gain, autoimmune exacerbations, and metabolic alterations.

However, epidemiological studies with longer follow-up periods are now emerging. In a prospective cohort study by Huttner et al[32] in 2019 involving 109 patients followed for 12-24 months post-FMT, no statistically significant increase in autoimmune or metabolic diseases was observed compared to matched controls. Similarly, Allegretti et al[33] in 2021 conducted a 5-year follow-up on 78 patients and reported a low incidence (under 2%) of new-onset chronic diseases, with no clear causal links to FMT.

Furthermore, systematic reviews suggest that while FMT can transiently alter host metabolism, there is no consistent pattern of increased risk for obesity, diabetes, or inflammatory conditions in long-term recipients. Nonetheless, post-FMT surveillance registries (e.g., the American Gastroenterological Association FMT National Registry) continue to track long-term outcomes to better quantify these risks across broader populations and diverse disease contexts.

Despite promising trends, the possibility of horizontal gene transfer, microbiome-induced immune modulation, or unexpected dysbiosis shifts over time cannot be entirely ruled out. Therefore, standardized long-term monitoring protocols are essential, especially in vulnerable populations such as children, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals.

Although specific FMT preparation protocols may differ across institutions, core procedures are largely consistent. Once a donor is approved, stool is collected in sterile containers and generally processed within six hours[34,35]. The standard preparation process involves blending approximately 50 g to 60 g of stool with a diluent - such as sterile saline, water, or milk - to create a smooth suspension. This mixture is then filtered to remove solid particles and divided into aliquots for immediate use or freezing.

For institutions using frozen stool, cryopreservatives are added before samples are stored at -80 °C. This method helps preserve microbial viability and supports the establishment of centralized stool banks, which improve accessibility and consistency across clinical settings. Frozen samples can later be thawed and administered via colonoscopy or enema, or processed into acid-resistant capsules for oral delivery.

Capsule-based FMT offers several advantages, including reduced procedural risk, increased patient compliance, and greater cost-effectiveness. A typical dose consists of 30 capsules to 40 capsules containing processed and freeze-dried fecal material. Although encapsulated FMT is a relatively new approach, early research indicates that its efficacy is comparable to colonoscopic infusion for treating rCDI.

Ongoing improvements in fecal material processing are focused on standardizing protocols and enhancing the safety, stability, and scalability of FMT therapies. These refinements are essential for advancing FMT from experimental use to routine clinical practice.

The safety and effectiveness of FMT depend significantly on the thorough screening of potential stool donors[36,37]. Comprehensive donor selection protocols are necessary to minimize the risk of transmitting infectious agents or in

Inclusion criteria typically require donors to be healthy adults between 18 years old and 65 years old, with a stable body mass index, no history of gastrointestinal disease, and no recent use of antibiotics, probiotics, or immunosuppres

Exclusion criteria are extensive and designed to further protect recipients. Potential donors are excluded if they have engaged in high-risk behaviors - such as recent travel to regions with endemic diarrheal diseases, a history of sexually transmitted infections, recent tattoos or piercings, or incarceration. Individuals with known gastrointestinal disorders, active malignancies, or systemic autoimmune diseases are also excluded.

Comprehensive laboratory testing is mandatory and includes blood tests for HIV, hepatitis A, B, and C, syphilis, and other systemic infections. Stool analyses are performed to detect bacterial pathogens, parasites, viruses, and toxins. For ongoing donors, periodic re-screening is required to ensure continued eligibility. Strict adherence to these screening protocols is critical for maximizing recipient safety and maintaining the clinical integrity of the FMT procedure.

The regulatory landscape for FMT is notably diverse across the globe and continues to develop as clinical applications grow. In the United States, the FDA defines FMT both as a biological product and a drug. Presently, the FDA permits FMT for rCDI under a policy of enforcement discretion when conventional treatments have failed; any other use requires submission of an Investigational New Drug application[40].

Canada treats FMT as a “New Biologic Drug”, mandating clinical trial authorization and strict adherence to quality assurance protocols. In the United Kingdom, FMT is regulated under the Medicines Act as an unlicensed medicinal product that may be prepared and administered under specific, controlled circumstances. Regulatory approaches in Europe vary, with some countries categorizing FMT as a tissue-based therapy, others as a medicinal product, and some as a specialized medical procedure.

Ethical considerations play a central role in FMT practice. Obtaining informed consent is essential, with both donors and recipients needing clear communication regarding potential risks, benefits, and the specifics of the procedure. This includes discussing the risk of transmitting unidentified pathogens, the possibility of immune reactions, and uncertainties about long-term health effects.

As FMT becomes more widely integrated into clinical care, there is a growing imperative for internationally har

FMT is primarily indicated for individuals with recurrent or refractory CDI, particularly after two or more unsuccessful attempts with standard antibiotic therapy. In these cases, FMT consistently achieves cure rates exceeding 85%, est

Interest is increasing in the potential use of FMT for other conditions associated with gut dysbiosis, including IBD, IBS, hepatic encephalopathy, metabolic syndrome, and certain neurological disorders. However, these applications remain experimental and are not yet part of standard clinical practice.

Absolute contraindications for FMT have not been universally established, but special caution is warranted in patients with significant immunosuppression, critical illness, or recent organ transplantation. For these individuals, a comprehensive evaluation of risks and benefits by a multidisciplinary healthcare team is essential before proceeding. The selection of the delivery method, donor material, and consideration of the recipient’s overall health should be tailored to each patient to maximize therapeutic success and safety.

Standard treatment protocols typically involve a short course of antibiotics prior to FMT to reduce C. difficile load, followed by bowel preparation if the procedure is to be performed via colonoscopy. Close post-procedure monitoring is recommended to assess symptom resolution and to promptly identify any early signs of recurrence or complications.

Most individuals who undergo FMT for rCDI see a marked improvement in symptoms within several days. Typically, bowel habits return to normal within one to two weeks post-procedure. Vigilant follow-up is crucial during the initial month, as this period is most likely to reveal treatment failures or the return of infection[41-43].

A recurrence is identified when symptoms re-emerge alongside a positive stool test for C. difficile after an initial period of improvement. While overall failure rates are low, non-response or relapse can be classified into three main types: (1) Primary non-responders: Symptoms do not resolve during the first week after FMT; (2) Early secondary non-responders: Symptoms recur within the first four weeks following initial improvement; and (3) Late secondary non-responders: Symptoms reappear more than four weeks after the procedure.

For patients with severe or persistent infection, multiple FMT procedures - sometimes in combination with oral vancomycin - have proven highly effective, with cure rates approaching 90% in such challenging cases. Following FMT, routine clinical evaluations and laboratory tests are recommended to monitor for adverse effects and confirm ongoing symptom relief. Although comprehensive long-term safety information is still being gathered, most reported side effects are mild and resolve on their own. Close monitoring is particularly important for high-risk or immunocompromised patients to promptly address any recurrence or complications that may arise.

Although FMT is currently authorized only for rCDI, expanding research is exploring its potential in a wide range of other health conditions. Early clinical trials and observational studies indicate that FMT might be beneficial for disorders such as IBD (including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease), IBS, hepatic encephalopathy, metabolic syndrome, allergies, and even certain psychiatric and neurodegenerative illnesses[44,45].

A core hypothesis behind these investigations is that imbalances in the gut microbiota - known as dysbiosis - play a significant role in the onset and progression of these diseases. By reinstating a healthy and diverse microbiota, FMT could help improve disease outcomes. The ability of FMT to modulate immune function, control inflammation, and influence metabolic and neurological processes provides a compelling basis for its study in these new areas. Nonetheless, most of these applications are still experimental, with results showing mixed effectiveness and a clear demand for more robust clinical evidence.

Recent research has drawn attention to FMT’s effects on serotonin metabolism, especially in individuals with IBS[46]. Because serotonin is mainly produced in the gut and influences gastrointestinal movement and sensation, disturbances in the gut microbiome can alter its levels. FMT may help restore normal serotonin signaling, which could contribute to symptom relief. Furthermore, elevated butyric acid production after FMT has been linked to improved immune regulation and reduced intestinal permeability.

While these preliminary findings are promising, additional well-structured clinical trials - including randomized controlled studies - are essential to confirm the safety, efficacy, and biological mechanisms of FMT for these emerging uses. Only through rigorous research can the full therapeutic potential of FMT be realized and safely applied to a broader range of conditions.

Even as FMT demonstrates notable clinical effectiveness for rCDI and shows promise for various other disorders, several persistent challenges limit its broader application. A foremost issue is the potential for transmitting unrecognized pathogens or triggering unforeseen immune responses. While adverse effects are uncommon, they can be severe, especially if donor screening is inadequate or patient eligibility criteria are not strictly followed[47].

A further obstacle is the absence of standardized procedures governing critical FMT processes such as donor selection, stool preparation, delivery techniques, and post-treatment monitoring. Inconsistencies in how FMT is performed can affect both its safety and efficacy. The gut microbiome is also inherently variable, shaped by dietary habits, antibiotic use, and individual health status, which complicates efforts to achieve consistent and predictable results with FMT.

To promote greater uniformity and support wider clinical use, the creation of comprehensive clinical guidelines and robust regulatory standards is imperative. Establishing international stool banks that employ universal donor models could enhance both accessibility and procedural standardization. Long-term safety research and the implementation of FMT registries to systematically record patient outcomes and potential complications are also essential for ongoing improvement.

Looking to the future, innovations such as synthetic microbiota preparations or therapies targeting specific microbial communities may offer more controlled and precise alternatives to conventional FMT. Until these advanced options are thoroughly validated and available, FMT remains a valuable and continually evolving therapeutic strategy, particularly for patients with recurrent C. difficile infection and potentially for a wider array of disorders linked to gut dysbiosis.

A major barrier to the widespread clinical adoption of FMT is the lack of standardized protocols across institutions. Variability exists in almost every stage of FMT processing - including the type of diluent used (e.g., saline, sterile water, glycerol), homogenization techniques, filtration pore sizes, and the freezing and thawing procedures. Such inconsistencies can affect the viability and diversity of microbiota in the final transplant product, leading to unpredictable therapeutic outcomes. Furthermore, there is no universal consensus on optimal storage duration, cryoprotectant concentration, or best practices for encapsulation vs enema delivery. These inconsistencies hinder reproducibility across clinical trials and real-world settings, complicating regulatory approval and broad-scale deployment. Developing consensus-driven guidelines and harmonized protocols is therefore essential to ensuring quality control, patient safety, and clinical success.

With increasing understanding of the complexity and individuality of the gut microbiome, future developments in FMT are moving toward standardized, reproducible, and targeted alternatives. Two key frontiers include synthetic microbial consortia and personalized microbiome-based therapies.

Synthetic microbiota refers to defined, cultured bacterial consortia designed to mimic the functional composition of healthy donor feces. These lab-cultivated mixtures aim to eliminate the risks associated with donor variability, pathogen transmission, and ethical constraints.

A purified spore-based microbiome therapeutic derived from Firmicutes species, showing efficacy in reducing recurrent C. difficile infections in phase III trials.

A rationally designed consortium of non-pathogenic Clostridia strains that promotes colonization resistance and mucosal immune modulation.

These formulations are undergoing clinical validation and are envisioned to become the future substitutes for tradi

The shift toward precision microbiome medicine involves customizing microbial interventions based on: Patient’s microbiome profile; disease phenotype; genetic predisposition; and immune status.

Advancements in metagenomics, metabolomics, and machine learning algorithms now allow for the development of individualized FMT formulations and predictive response modeling. For instance, efforts are underway to create “microbiome matching” algorithms, akin to donor matching in organ transplantation, to optimize therapeutic compatibility and efficacy. Personalized approaches may also integrate adjunctive therapies such as: Dietary modulation, prebiotics, phage therapy, immune checkpoint modifiers.

Immune checkpoint modifiers: However, the implementation faces technical, ethical, and economic hurdles, including the need for high-throughput microbiome profiling, regulatory frameworks for synthetic products, and cost-effectiveness analysis.

Patient monitoring and safety: Close and ongoing patient monitoring is essential after FMT to confirm therapeutic effectiveness and to promptly identify any adverse effects[48]. Most individuals experience symptom improvement within a few days, with bowel habits typically returning to normal within one to two weeks. However, careful follow-up - particularly during the first eight weeks - is vital for detecting recurrence or complications. Recommended monitoring includes regular clinical assessments, stool testing when necessary, and laboratory investigations to check for signs of inflammation or infection.

While FMT is generally considered safe, rare but serious complications can occur. These may include systemic in

Regulatory considerations: Regulatory oversight of FMT varies globally and continues to evolve as clinical practice advances. In the United States, the FDA categorizes FMT as both a drug and a biological product. Its use is permitted for rCDI under enforcement discretion when standard therapies fail, while other indications require an Investigational New Drug application. In Canada and the European Union, FMT is regulated as a new biologic or tissue-based product, requiring strict adherence to quality and safety standards, clinical trial approval, and controlled distribution. In the United Kingdom, FMT is governed by the Medicines Act and may be administered under specific exemptions with appropriate oversight[49].

To ensure safe and ethical use, informed consent must clearly outline the risks, potential benefits, available alternatives, and areas of uncertainty associated with FMT. Moving forward, advancements in regulatory frameworks, donor biobanking, quality assurance, and international harmonization will be crucial for the ongoing integration of FMT into evidence-based clinical practice[48]. These efforts will help maximize patient safety and support the responsible ex

FMT has become a highly effective and dependable therapy for rCDI, consistently demonstrating cure rates that surpass those of traditional antibiotic treatments. By reintroducing a healthy and diverse array of gut microorganisms, FMT provides a transformative option for patients whose gut microbiota has been disrupted by antibiotics or chronic disease. Its success in rCDI has paved the way for research into broader applications.

Beyond rCDI, FMT is being actively explored for a variety of conditions associated with gut dysbiosis, including IBD, IBS, metabolic and allergic disorders, and certain neurological diseases. While early results are promising, these wider uses remain investigational, highlighting the necessity for additional high-quality clinical trials and the development of standardized protocols.

The future expansion and successful integration of FMT into routine clinical practice will depend on several critical factors. These include the establishment of universal donor screening guidelines, standardized methods for stool pre

As our understanding of the gut microbiome continues to grow, FMT not only stands as a powerful therapeutic tool but also serves as a foundation for the development of next-generation microbiota-based therapies. Ongoing research, multidisciplinary collaboration, and a strong commitment to patient safety are essential for realizing the full clinical potential of FMT and ensuring its responsible use in diverse patient populations.

I acknowledge my sincere thanks to Maharajah’s College of Pharmacy, Vizianagaram in successful completion of this work.

| 1. | Mullish BH, Merrick B, Quraishi MN, Bak A, Green CA, Moore DJ, Porter RJ, Elumogo NT, Segal JP, Sharma N, Marsh B, Kontkowski G, Manzoor SE, Hart AL, Settle C, Keller JJ, Hawkey P, Iqbal TH, Goldenberg SD, Williams HRT. The use of faecal microbiota transplant as treatment for recurrent or refractory Clostridioides difficile infection and other potential indications: second edition of joint British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and Healthcare Infection Society (HIS) guidelines. J Hosp Infect. 2024;148:189-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wang JW, Kuo CH, Kuo FC, Wang YK, Hsu WH, Yu FJ, Hu HM, Hsu PI, Wang JY, Wu DC. Fecal microbiota transplantation: Review and update. J Formos Med Assoc. 2019;118 Suppl 1:S23-S31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 369] [Cited by in RCA: 373] [Article Influence: 53.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sbahi H, Di Palma JA. Faecal microbiota transplantation: applications and limitations in treating gastrointestinal disorders. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016;3:e000087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Peery AF, Kelly CR, Kao D, Vaughn BP, Lebwohl B, Singh S, Imdad A, Altayar O; AGA Clinical Guidelines Committee. AGA Clinical Practice Guideline on Fecal Microbiota-Based Therapies for Select Gastrointestinal Diseases. Gastroenterology. 2024;166:409-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 61.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kelly CR, Yen EF, Grinspan AM, Kahn SA, Atreja A, Lewis JD, Moore TA, Rubin DT, Kim AM, Serra S, Nersesova Y, Fredell L, Hunsicker D, McDonald D, Knight R, Allegretti JR, Pekow J, Absah I, Hsu R, Vincent J, Khanna S, Tangen L, Crawford CV, Mattar MC, Chen LA, Fischer M, Arsenescu RI, Feuerstadt P, Goldstein J, Kerman D, Ehrlich AC, Wu GD, Laine L. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Is Highly Effective in Real-World Practice: Initial Results From the FMT National Registry. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:183-192.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 30.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cheng YW, Phelps E, Nemes S, Rogers N, Sagi S, Bohm M, El-Halabi M, Allegretti JR, Kassam Z, Xu H, Fischer M. Fecal Microbiota Transplant Decreases Mortality in Patients with Refractory Severe or Fulminant Clostridioides difficile Infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:2234-2243.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kim KO, Gluck M. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: An Update on Clinical Practice. Clin Endosc. 2019;52:137-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | El-Salhy M, Patcharatrakul T, Gonlachanvit S. Fecal microbiota transplantation for irritable bowel syndrome: An intervention for the 21(st) century. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:2921-2943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Tüsüz Önata E, Özdemir Ö. Fecal microbiota transplantation in allergic diseases. World J Methodol. 2025;15:101430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (12)] |

| 10. | Martinez-Guryn K, Leone V, Chang EB. Regional Diversity of the Gastrointestinal Microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;26:314-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 51.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gomaa EZ. Human gut microbiota/microbiome in health and diseases: a review. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2020;113:2019-2040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 793] [Article Influence: 132.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 12. | Brandt LJ, Aroniadis OC. An overview of fecal microbiota transplantation: techniques, indications, and outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:240-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kelly CR, Ihunnah C, Fischer M, Khoruts A, Surawicz C, Afzali A, Aroniadis O, Barto A, Borody T, Giovanelli A, Gordon S, Gluck M, Hohmann EL, Kao D, Kao JY, McQuillen DP, Mellow M, Rank KM, Rao K, Ray A, Schwartz MA, Singh N, Stollman N, Suskind DL, Vindigni SM, Youngster I, Brandt L. Fecal microbiota transplant for treatment of Clostridium difficile infection in immunocompromised patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1065-1071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 431] [Cited by in RCA: 506] [Article Influence: 42.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Gu J, Han B, Wang J. COVID-19: Gastrointestinal Manifestations and Potential Fecal-Oral Transmission. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1518-1519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 954] [Cited by in RCA: 950] [Article Influence: 158.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 15. | Thursby E, Juge N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem J. 2017;474:1823-1836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1710] [Cited by in RCA: 2201] [Article Influence: 244.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 16. | Wilson BC, Vatanen T, Cutfield WS, O'Sullivan JM. The Super-Donor Phenomenon in Fecal Microbiota Transplantation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2019;9:2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 39.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Liubakka A, Vaughn BP. Clostridium difficile Infection and Fecal Microbiota Transplant. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2016;27:324-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Green JE, Davis JA, Berk M, Hair C, Loughman A, Castle D, Athan E, Nierenberg AA, Cryan JF, Jacka F, Marx W. Efficacy and safety of fecal microbiota transplantation for the treatment of diseases other than Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut Microbes. 2020;12:1-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Modi SR, Collins JJ, Relman DA. Antibiotics and the gut microbiota. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:4212-4218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 398] [Cited by in RCA: 470] [Article Influence: 39.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Pinn DM, Aroniadis OC, Brandt LJ. Is fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) an effective treatment for patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGID)? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:19-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhao HL, Chen SZ, Xu HM, Zhou YL, He J, Huang HL, Xu J, Nie YQ. Efficacy and safety of fecal microbiota transplantation for treating patients with ulcerative colitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dig Dis. 2020;21:534-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sadowski K, Zając W, Milanowski Ł, Koziorowski D, Figura M. Exploring Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Modulating Inflammation in Parkinson's Disease: A Review of Inflammatory Markers and Potential Effects. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:7741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Keller JJ, Ooijevaar RE, Hvas CL, Terveer EM, Lieberknecht SC, Högenauer C, Arkkila P, Sokol H, Gridnyev O, Mégraud F, Kump PK, Nakov R, Goldenberg SD, Satokari R, Tkatch S, Sanguinetti M, Cammarota G, Dorofeev A, Gubska O, Ianiro G, Mattila E, Arasaradnam RP, Sarin SK, Sood A, Putignani L, Alric L, Baunwall SMD, Kupcinskas J, Link A, Goorhuis AG, Verspaget HW, Ponsioen C, Hold GL, Tilg H, Kassam Z, Kuijper EJ, Gasbarrini A, Mulder CJJ, Williams HRT, Vehreschild MJGT. A standardised model for stool banking for faecal microbiota transplantation: a consensus report from a multidisciplinary UEG working group. United European Gastroenterol J. 2021;9:229-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kazerouni A, Wein LM. Exploring the Efficacy of Pooled Stools in Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Microbiota-Associated Chronic Diseases. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0163956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Paramsothy S, Kamm MA, Kaakoush NO, Walsh AJ, van den Bogaerde J, Samuel D, Leong RWL, Connor S, Ng W, Paramsothy R, Xuan W, Lin E, Mitchell HM, Borody TJ. Multidonor intensive faecal microbiota transplantation for active ulcerative colitis: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:1218-1228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 710] [Cited by in RCA: 930] [Article Influence: 103.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | El-Salhy M. FMT in IBS: how cautious should we be? Gut. 2021;70:626-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hamamah S, Gheorghita R, Lobiuc A, Sirbu IO, Covasa M. Fecal microbiota transplantation in non-communicable diseases: Recent advances and protocols. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:1060581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Johnsen PH, Hilpüsch F, Cavanagh JP, Leikanger IS, Kolstad C, Valle PC, Goll R. Faecal microbiota transplantation versus placebo for moderate-to-severe irritable bowel syndrome: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, single-centre trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3:17-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 39.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Halkjær SI, Christensen AH, Lo BZS, Browne PD, Günther S, Hansen LH, Petersen AM. Faecal microbiota transplantation alters gut microbiota in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: results from a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled study. Gut. 2018;67:2107-2115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Keller JJ, Vehreschild MJ, Hvas CL, Jørgensen SM, Kupciskas J, Link A, Mulder CJ, Goldenberg SD, Arasaradnam R, Sokol H, Gasbarrini A, Hoegenauer C, Terveer EM, Kuijper EJ, Arkkila P; UEG working group of the Standards and Guidelines initiative Stool banking for FMT. Stool for fecal microbiota transplantation should be classified as a transplant product and not as a drug. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7:1408-1410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Dailey FE, Turse EP, Daglilar E, Tahan V. The dirty aspects of fecal microbiota transplantation: a review of its adverse effects and complications. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2019;49:29-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Huttner BD, de Lastours V, Wassenberg M, Maharshak N, Mauris A, Galperine T, Zanichelli V, Kapel N, Bellanger A, Olearo F, Duval X, Armand-Lefevre L, Carmeli Y, Bonten M, Fantin B, Harbarth S; R-Gnosis WP3 study group. A 5-day course of oral antibiotics followed by faecal transplantation to eradicate carriage of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25:830-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Allegretti JR, Mehta SR, Kassam Z, Kelly CR, Kao D, Xu H, Fischer M. Risk Factors that Predict the Failure of Multiple Fecal Microbiota Transplantations for Clostridioides difficile Infection. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66:213-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Blaser MJ. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Dysbiosis - Predictable Risks. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2064-2066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Wang S, Xu M, Wang W, Cao X, Piao M, Khan S, Yan F, Cao H, Wang B. Systematic Review: Adverse Events of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 26.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Winston JA, Suchodolski JS, Gaschen F, Busch K, Marsilio S, Costa MC, Chaitman J, Coffey EL, Dandrieux JR, Gal A, Hill T, Pilla R, Procoli F, Schmitz SS, Tolbert MK, Toresson L, Unterer S, Valverde-altamirano É, Verocai GG, Werner M, Ziese A. Clinical Guidelines for Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Companion Animals. Adv Small Anim Care. 2024;5:79-107. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 37. | Barbara G, Ianiro G. Faecal microbial transplantation in IBS: ready for prime time? Gut. 2020;69:795-796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Camilleri M. FMT in IBS: a call for caution. Gut. 2021;70:431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Carlson PE Jr. Regulatory Considerations for Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Products. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:173-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Perler BK, Chen B, Phelps E, Allegretti JR, Fischer M, Ganapini V, Krajiceck E, Kumar V, Marcus J, Nativ L, Kelly CR. Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Treatment of Recurrent Clostridioides difficile Infection. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;54:701-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | El-Salhy M, Solomon T, Hausken T, Gilja OH, Hatlebakk JG. Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine peptides/amines in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:5068-5085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 42. | El-Salhy M. Irritable bowel syndrome: diagnosis and pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5151-5163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Ng RW, Dharmaratne P, Wong S, Hawkey P, Chan P, Ip M. Revisiting the donor screening protocol of faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT): a systematic review. Gut. 2024;73:1029-1031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | El-Salhy M. Recent developments in the pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:7621-7636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | El-Salhy M, Casen C, Valeur J, Hausken T, Hatlebakk JG. Responses to faecal microbiota transplantation in female and male patients with irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:2219-2237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Lessa FC, Mu Y, Bamberg WM, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati GK, Dunn JR, Farley MM, Holzbauer SM, Meek JI, Phipps EC, Wilson LE, Winston LG, Cohen JA, Limbago BM, Fridkin SK, Gerding DN, McDonald LC. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:825-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2023] [Cited by in RCA: 2013] [Article Influence: 183.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 47. | Bakken JS, Borody T, Brandt LJ, Brill JV, Demarco DC, Franzos MA, Kelly C, Khoruts A, Louie T, Martinelli LP, Moore TA, Russell G, Surawicz C; Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Workgroup. Treating Clostridium difficile infection with fecal microbiota transplantation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:1044-1049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 650] [Cited by in RCA: 702] [Article Influence: 46.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Youngster I, Russell GH, Pindar C, Ziv-Baran T, Sauk J, Hohmann EL. Oral, capsulized, frozen fecal microbiota transplantation for relapsing Clostridium difficile infection. JAMA. 2014;312:1772-1778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 466] [Cited by in RCA: 490] [Article Influence: 40.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Choi HH, Cho YS. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: Current Applications, Effectiveness, and Future Perspectives. Clin Endosc. 2016;49:257-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 50. | Cammarota G, Ianiro G, Gasbarrini A. Fecal microbiota transplantation for the treatment of Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:693-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 362] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (12)] |