Published online Sep 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i9.110476

Revised: July 7, 2025

Accepted: August 4, 2025

Published online: September 16, 2025

Processing time: 97 Days and 15 Hours

Colonoscopy is essential for screening, diagnosing, and treating lower gastroin

To evaluate the findings, success, and impact of weekend outreach colonoscopy services in predominantly rural Southwest Ethiopia.

In partnership with Jimma Awetu Hospital, a senior gastroenterologist from Addis Ababa University established an outreach endoscopy service in 2019, training local nursing staff as coordinators. Physicians selected and referred patients for colonoscopy, and informed consent was obtained before the procedure. A total of 1612 procedures were performed using a portable Fujinon EPX-2500-HD system, and findings were documented electronically. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics on Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 29.

From 2019 to 2024 1612 colonoscopy procedures were performed, achieving an 83.0% diagnostic yield. The cohort was predominantly male (70.6%) with a mean age of 44 years; 61% were under 50. Ninety-one percent of patients were referred by 21 hospitals across three regions. Primary indications included abdominal pain (26.8%) and lower gastrointestinal bleeding (25.3%). Abnormal findings included inflammation (39.5%), colorectal masses (13.2%), and hemorrhoid (11.8%). Histology confirmed inflammatory bowel disease in 11.5%, cancers in 11.0%, and polyps in 10.0%. In this study half of colorectal cancer cases occurred in patients under 50 with prevalence rates of 18.8% in females and 10.8% in males, challenging the global trend that shows this disease predominantly affects older individuals and males.

This weekend outreach colonoscopy service implemented standard diagnostics, improved the existing service, and generated vital evidence on local disease patterns with the potential to positively impact clinical practice and policy-making.

Core Tip: Over the past 6 years, we have performed over 6000 endoscopy procedures at an outreach site in southwest Ethiopia, a region lacking a functional endoscopy unit. Among the 1612 colonoscopy findings, the most common were nonspecific inflammation, colorectal masses, inflammatory bowel disease, and polyps. Notably, half of the colorectal cancer cases in this study occurred in patients under 50 with a prevalence of 18.8% in females and 10.8% in males. This contradicts the global trend in which the disease predominantly affects males and older individuals. Less than 5.0% of all patients underwent colonoscopy for screening or suspected colorectal cancer.

- Citation: Roro GM, Roro EM, Abebe DM. Addressing gastrointestinal disorders in rural Ethiopia: Success of a weekend outreach colonoscopy service. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(9): 110476

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i9/110476.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i9.110476

Colonoscopy is the gold standard diagnostic test for lower gastrointestinal (GI) tract symptoms, enabling direct mucosal visualization, tissue acquisition, and when necessary surveillance and therapeutic interventions[1-5]. Studies have reported minimal risk of adverse events[6-8]. Advancements in GI endoscopy knowledge and technology have enhanced its significance, and it is increasingly replacing radiology and surgery[9]. Notably, progress in endoscopic resection procedures has made colonoscopy a common treatment for polyps and early colorectal cancer (CRC)[10].

Despite the heavy burden of GI diseases, including malignancies, many African countries lack adequately resourced GI endoscopy centers[11-14]. Barriers to developing these services include a shortage of trained specialists and insufficient equipment and infrastructure[13,14]. In Ethiopia most trained GI specialists work in hospitals located in large cities while 80% of the population lives in rural areas where access to endoscopy services is limited due to economic and logistical challenges. This lack of access significantly impairs optimal patient care and outcomes, leading to underdiagnosis and underreporting of critical disease conditions among those without access to diagnostic services. Consequently, clinical and policy decisions are often based on findings from a less representative minority who utilize these scarce services.

Expanding endoscopy capacity requires significant investment in human and material resources as well as technological innovations to improve cost-effectiveness and sustainability[13,14]. One promising approach is mobilizing local resources through public-private partnerships. While most trained GI specialists in Ethiopia work in public teaching hospitals, private hospitals have the potential to invest in the necessary resources for establishing and sustaining endoscopy services. Although such collaborations are common in large cities, they are unusual in remote areas.

In response to this need, we established an outreach colonoscopy center in 2019, located 360 km southwest of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia, to enhance access for individuals from three major regions with a combined population of over 20 million where no functional endoscopy services previously existed[15]. Operating on weekends, our center has successfully provided diagnostic colonoscopy, upper GI endoscopy, and life-saving therapeutic procedures, including endoscopic variceal band ligation and foreign body removal. Previously, only small-scale outreach GI endoscopy services with limited reported outcomes have been documented in sub-Saharan Africa[16].

This study aimed to describe the patterns of lower GI diseases diagnosed through colonoscopy and biopsy among patients primarily from rural populations in southwest Ethiopia. Additionally, we shared our experiences regarding the success and potential impact of our weekend outreach colonoscopy service in a resource-limited setting, emphasizing its significance for improving GI care in similar contexts.

In collaboration with Jimma Awetu Hospital in Jimma city, Southwest Ethiopia, a senior gastroenterologist from Addis Ababa University established the outreach GI endoscopy service in 2019. Eight local nursing staff were trained in essential skills, including equipment handling, conscious sedation, patient appointment scheduling, bowel preparation, biopsy sample handling, and documentation. They coordinated the program and assisted during procedures.

Patients with appropriate indications for colonoscopy were selected and referred by their treating physicians.

Patients who were considered unfit for colonoscopy or bowel preparation due to major organ failures or pregnancy were excluded from the procedures. Additionally, data with incomplete patient or procedural information were excluded from the analysis.

Patients were instructed to follow a bowel preparation protocol that involved consuming only light meals starting 2 days before the procedure, taking only clear fluids for 1 day prior, using a combination of castor oil and bisacodyl for bowel preparation the day before the procedure, and refraining from all oral intake on the day of the procedure.

All procedures were conducted by the senior gastroenterologist using a compact, portable video processor, the Fujinon EPX-2500-HD system, in a dedicated three-room endoscopy unit within the hospital. Most patients did not require anesthetic medication with only a few procedures performed under conscious sedation.

Demographic, clinical, and colonoscopic findings were recorded on the day of the procedure using Microsoft Excel and stored on a desktop computer in the endoscopy room. Biopsy results, once known, were integrated into the system during subsequent visits.

All patients, or their legal guardians, provided informed written consent prior to the colonoscopy procedure. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jimma University Institute of Health (No. JUIH/IRB/359/23).

To maintain confidentiality, all individual patient identifiers were removed, and only anonymous data were analyzed. Data were exported to Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 29 for Windows in which descriptive statistics, including means and frequencies, were generated.

This study included data from all patients who underwent colonoscopy at the Jimma Awetu Hospital outreach service between 2019 and 2024. Detailed data is available upon request.

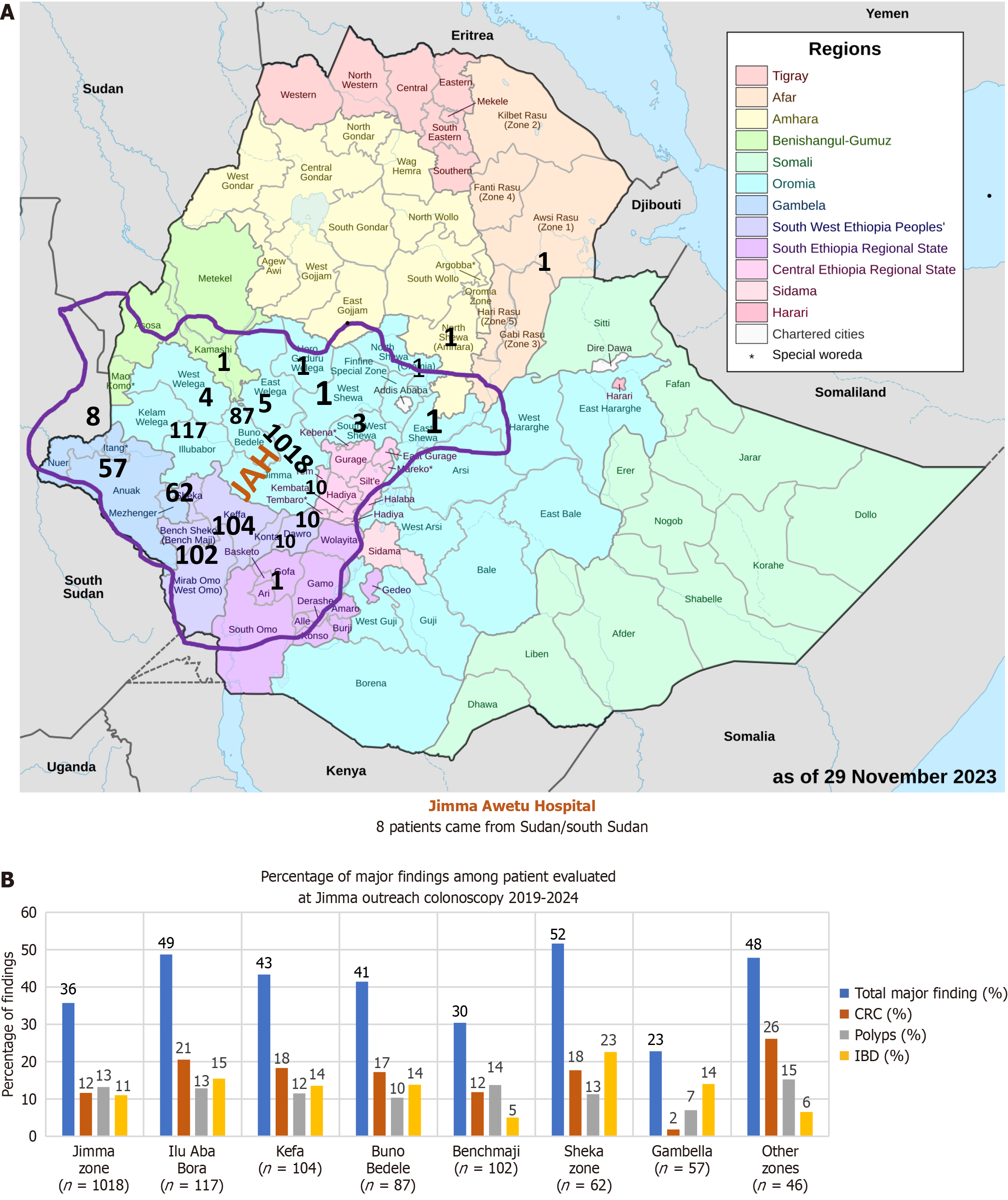

In the first 6 years, a total of 1612 colonoscopy procedures were performed, involving 1138 (70.6%) male and 474 (29.4%) female patients (Table 1). The mean age of the patients was 44.0 years (range: 7.0-100.0 years) with 981 (61.0%) patients younger than 50 years. The average duration of symptoms before undergoing colonoscopy was 21 months. The majority of patients, 1238 (76.8%), were from the Oromia region while 299 (18.5%) were from South/Southwestern Ethiopian Peoples’ region, and 67 (4.2%) were from the Gambella region (Figure 1A).

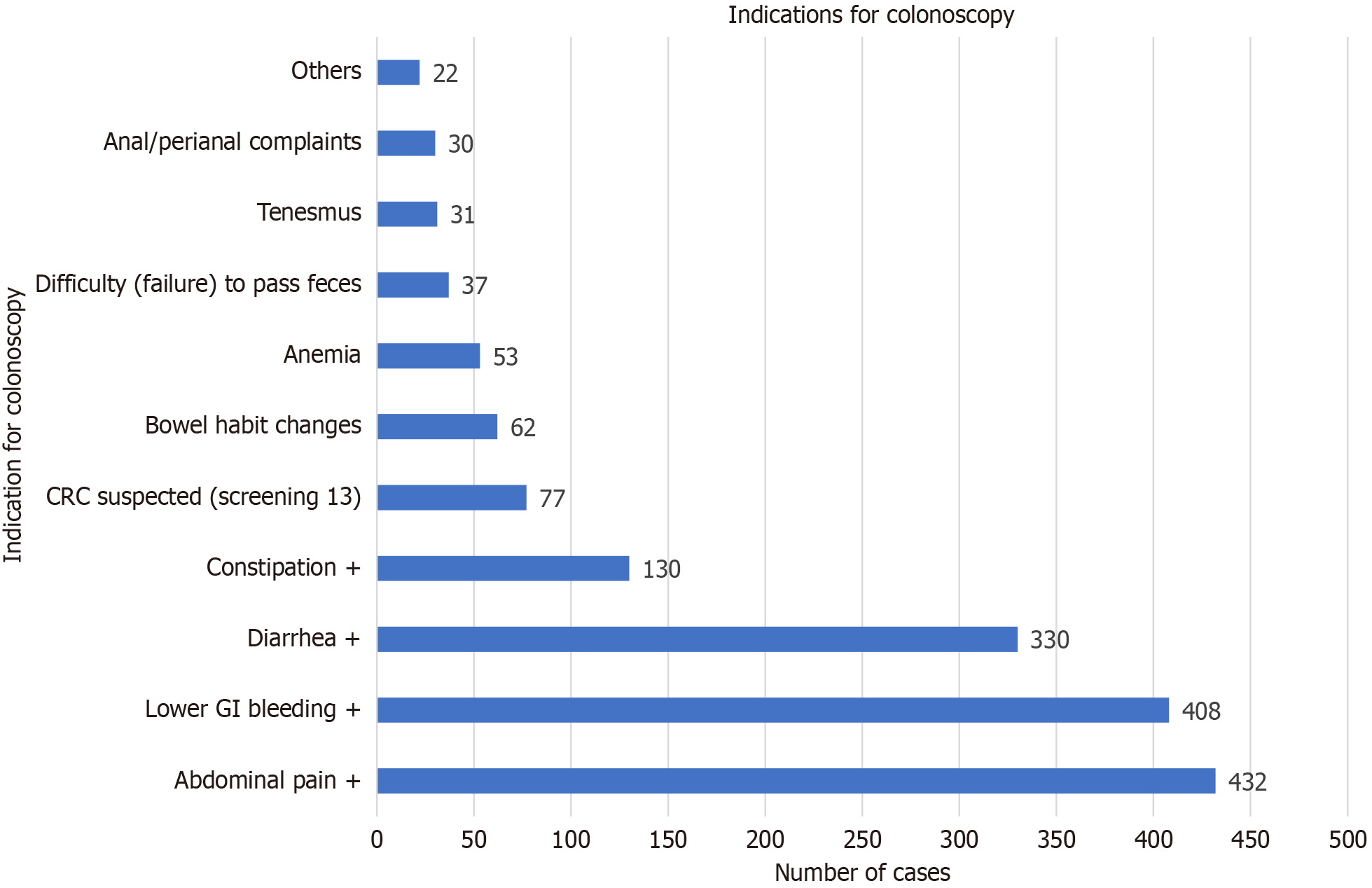

The most common indications for colonoscopy included abdominal pain 432 (27.0%), lower GI bleeding 408 (25.3%), diarrhea 330 (20.5%), and constipation 130 (8.1%) (Figure 2).

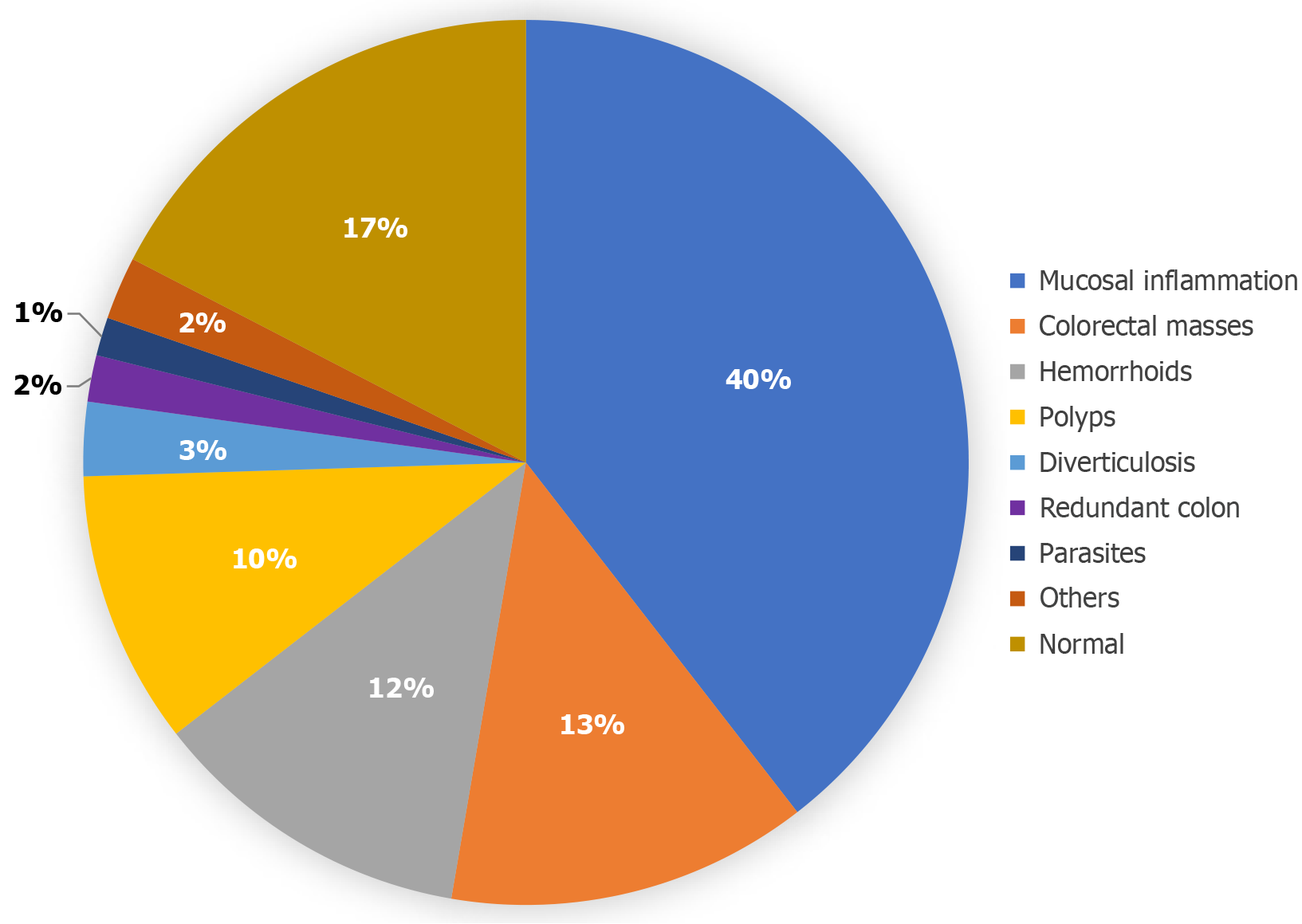

The most common colonoscopic findings included signs of inflammation (636 cases, 39.5%), colorectal masses (212 cases, 13.2%), hemorrhoids (191 cases, 11.8%), and polyps (160 cases, 10.0%) (Figure 3).

The average age of patients diagnosed with CRC was 48.0 years (range: 14.5-85.0 years). Nearly half of the patients with CRC (103 cases, 49%) were under 50 years old. The prevalence of CRC was 98/934 patients (10.5%) for those younger than 45 and 113/678 patients (16.7%) for those older than 45. Among female patients the prevalence was 89 out of 474 (18.8%) while in male patients, it was 123 out of 1138 (10.8%). Among the 212 patients with colorectal masses, the primary clinical symptoms leading to colonoscopy were lower GI bleeding (59.6%), tenesmus (26.4%), abdominal pain (24.0%), and constipation or difficulty passing feces (10.0%).

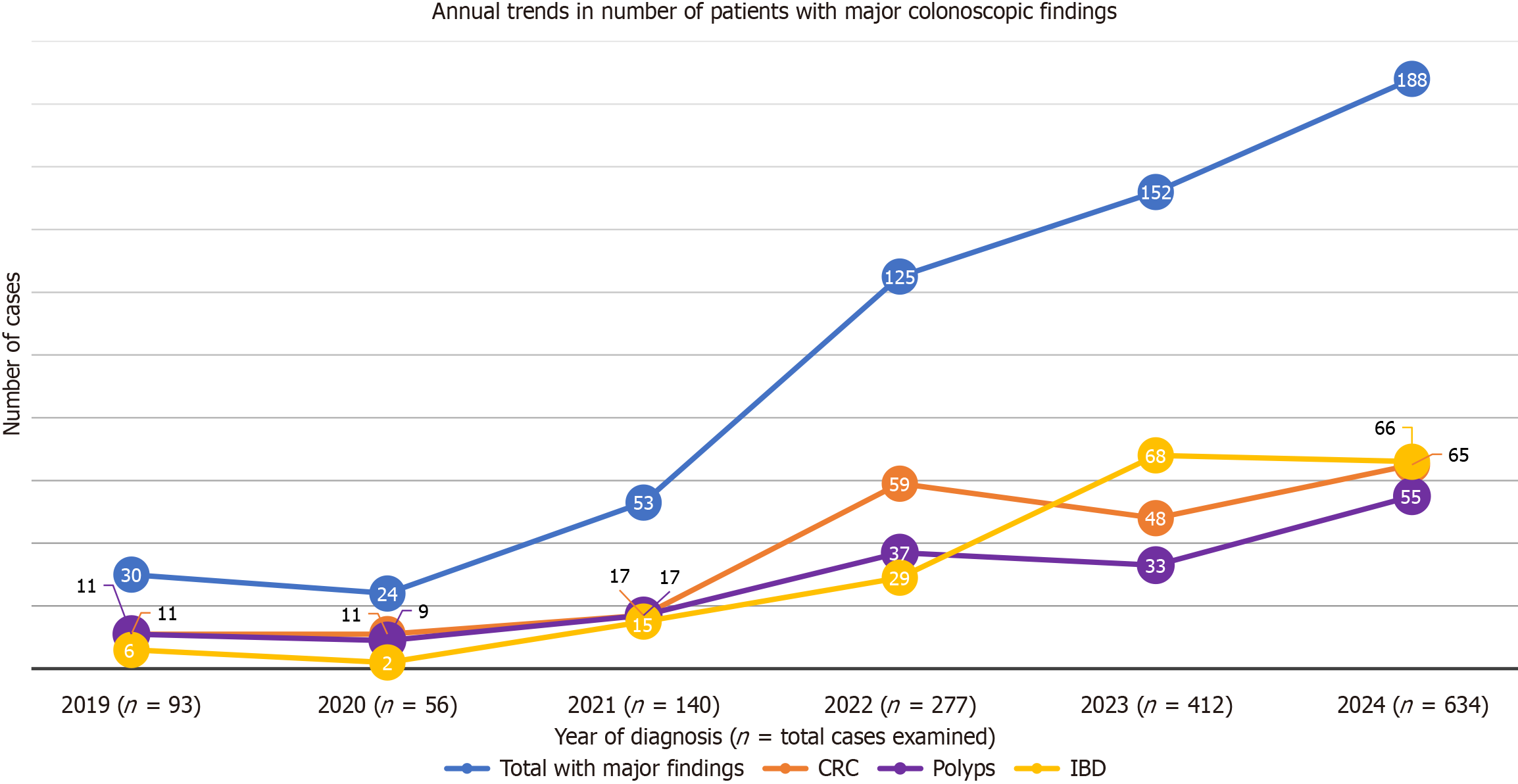

The total number of patients and those with significant colonoscopic findings increased each year over the past 6 years of service, except in 2019 and 2020 when a decline was observed due to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic (Figure 4).

Major findings included CRC, polyps, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), tuberculosis, and schistosomiasis. However, only the first three conditions are represented in the trend graph. It is important to note that patients with normal colonoscopic findings were not depicted in the graph.

The distribution of major colonoscopic findings varied across different regions and zones with Sheka and Ilu AbaBor zones exhibiting the highest proportions of CRC and IBD among the examined patients (Figure 1B).

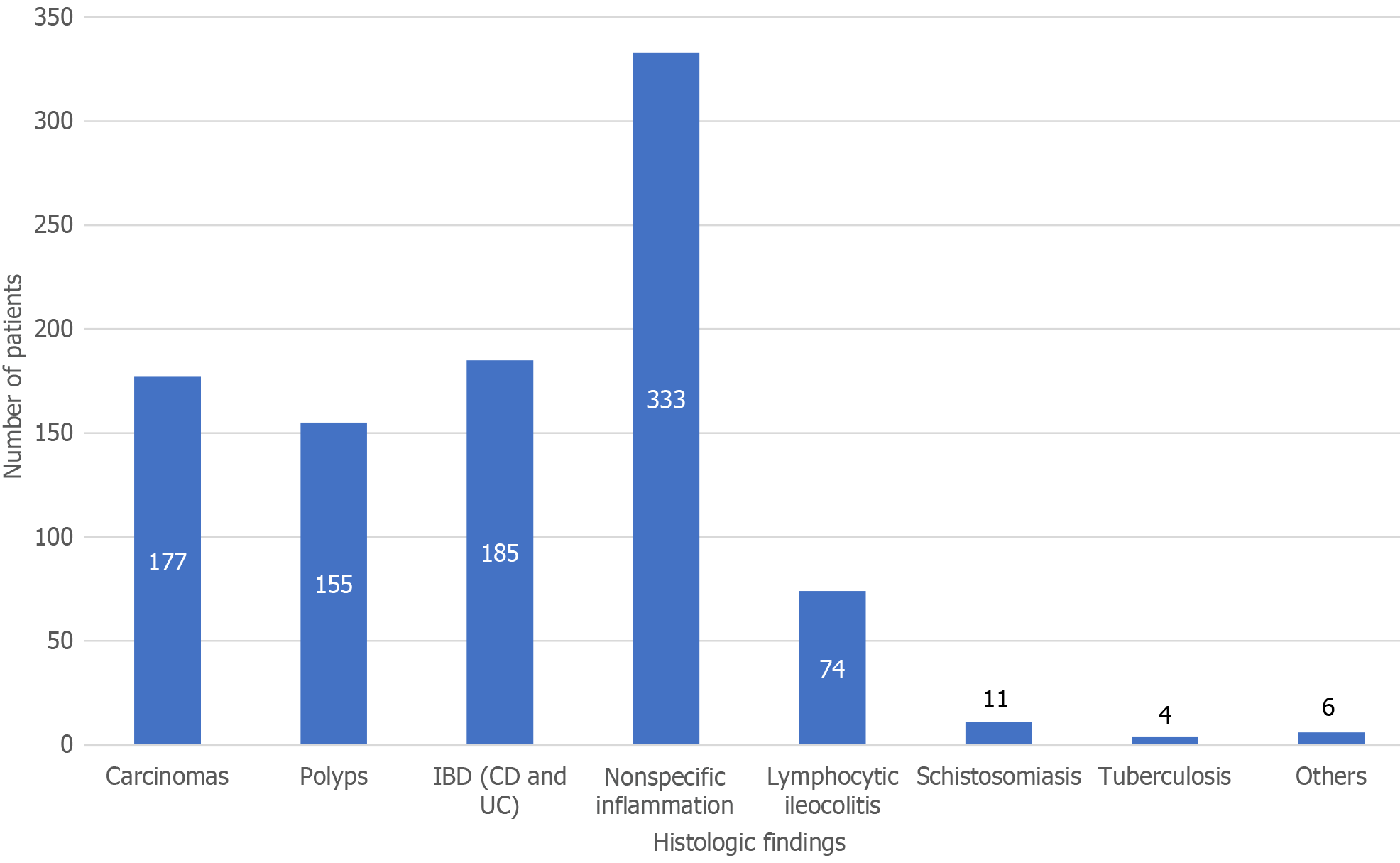

The results from 945 biopsy specimens were analyzed. The most common histological diagnoses included nonspecific inflammation in 222 (23.5%) patients, IBD in 185 (19.6%) patients, carcinomas in 177 (18.7%) patients, and polyps in 155 (16.4%) patients. Additionally, colorectal schistosomiasis was identified in 11 (1.2%) cases and tuberculosis in 4 (0.4%) cases (Figure 5). This indicates that malignancies accounted for 11.0%, IBD (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis) for 11.5%, and polyps for 9.6% of the total patients evaluated, representing the most significant specific diagnoses confirmed through histologic analysis.

As a result of hours of fasting and the diarrhea during bowel preparation, few patients developed hypotension and/or suspected mild hypoglycemia. They were administered intravenous fluid or supplemented with 40% glucose and recovered well. No other clinically significant adverse events were observed during or immediately after the procedures.

Ninety-one percent of the patients were referred by a total of 21 hospitals while the remaining 9% came from 32 clinics. The patients originated from 25 zones across three neighboring regions: (1) Oromia (77.0%); (2) The South/Southwest Ethiopian Peoples’ Region (18.5%); and (3) Gambella (4.0%). Some patients traveled as far as 450 km, requiring an 11-h drive to reach the center. The referrals from such a large number of health institutions across these three major regions, covering an area with a population of over 22 million[15], clearly indicate a significant service gap in that part of the country.

The mean duration of symptoms was 21 months with a median of 12 months, revealing systemic delays in diagnosis and treatment. This lag not only worsens patient outcomes but also contributes to more severe disease presentations. We observed concerning colonoscopic features indicative of delayed diagnosis, such as obstruction, gross ulceration, and bleeding in 80% of patients diagnosed with cancer. This suggests that many patients are reaching advanced stages of the disease before receiving necessary interventions. Furthermore, some individuals who underwent surgery for CRC years prior presented with metachronous symptomatic malignant lesions, which could have been detected and potentially prevented through postoperative surveillance colonoscopy.

Since the start of our program, we have identified a significant number of patients with polyps and removed small polyps on-site. Patients with large polyps were referred for snare polypectomy, and early cancers were diagnosed and referred for surgical intervention or chemoradiotherapy. Additionally, some patients have undergone their postoperative surveillance colonoscopy due to improved awareness and access to services.

Among patients with IBD severe pan colitis, strictures, and fistulae were documented in half of the cases, underscoring the delays in diagnosis as these patients were repeatedly treated for presumptive infectious conditions. Limited access to GI endoscopy services is similarly reported in many sub-Saharan African countries[14].

By introducing standard diagnostics, including endoscopy and biopsy services at an accessible outreach location and maintaining these services for over 6 years, our program successfully addressed the critical gap in GI healthcare in the regions. It also identified important findings with potential clinical and policy implications, which are discussed in subsequent sections. Establishing additional endoscopy services with trained full-time staff is highly recommended.

In developed countries the majority of colonoscopies are performed in older patients primarily for CRC screening with only about 20% conducted in patients under 50 years old for GI symptoms[17]. In contrast 61% of patients undergoing colonoscopy at our center are below the age of 50 with less than 1% of procedures performed for screening indications for CRC and only 4% for suspected CRC. Similar age distributions and indications for colonoscopy have been reported from other Ethiopian and African hospitals, indicating that colonoscopy services are primarily symptom-based with screening tests rarely practiced (0.5% in both St. Paul’s Hospital in Ethiopia and in a tertiary hospital in Ghana)[18,19]. Considering the significant role of screening colonoscopy in the prevention and early diagnosis of CRCs, it is imperative to raise awareness among practicing physicians in sub-Saharan Africa to maximize the utilization of available services targeting individuals at average and high risk for CRC[2,3,6,10].

The number of patients referred to our center for colonoscopy has dramatically increased over the years, rising from 93 procedures in the first year (2019) to 634 procedures annually in 2024 (a seven-fold increase). The service was successfully integrated with consistently improving acceptance by the referring doctors and their patients. Abnormal findings were identified in 83% of the total procedures performed. This diagnostic yield is comparable to reports from Ghana (84%)[19], and higher than that reported from St. Paul’s Hospital in Addis Ababa (72%)[18] and Mekelle (52%)[20].

Mucosal inflammation was the most common finding (636 cases, 40%), of which 185 cases were histologically proven IBD, constituting 29% of the inflammatory lesions and 12% of the total procedures. The high prevalence of inflammatory lesions aligns with findings from other African studies[18,20,21]; however, the prevalence of IBD among those with inflammation was significantly higher than the 1.4% reported from northern Ethiopia and is comparable to the 12% (37/309) reported from St. Paul’s Hospital in Addis Ababa[18,20].

Overall, 35% of the findings were categorized as major colonoscopic findings, including colorectal masses, polyps, IBD, tuberculosis, and schistosomiasis. The highest proportion of patients with major findings came from the Sheka Zone (52%), Ilu Ababor (49%), and Kefa (43%), zones where there was a notable prevalence of both cancer and IBD. As illustrated in Figure 4, the number of patients with major colonoscopic findings increased proportionally with the growing number of patients attending the service. Initially, CRCs dominated the major findings, peaking at 59 out of 277 cases (21.3%) in 2022. However, in subsequent years IBD cases took precedence, reaching 68 out of 412 cases (16.5%) in 2023.

Contrary to the general evidence that IBD and CRC are associated with higher sociodemographic index (SDI) and are considered uncommon in low-SDI regions like sub-Saharan Africa[22-26], our findings indicated that CRC (13%), IBD (12%), and polyps (11%) are among the most commonly diagnosed conditions. Another notable finding in our study was that CRC predominantly affected younger patients and females. While females represented only 29% of the patients examined, they accounted for 42% of the total CRC cases diagnosed. The prevalence of cancer in females (89/474 cases, 18.8%) was nearly double that in males (123/1138 cases, 10.8%). Typically, this disease is more prevalent in males and older individuals in most parts of the world[22-26]. The high burden among younger patients can be partly attributed to the fact that the majority of our patients were young. When analyzed by age group, the prevalence was 10.5% among those younger than 45 compared with 16.5% among those older than 45. However, the predominance of CRC in females warrants a closer examination of sex-related risk factors and exposures.

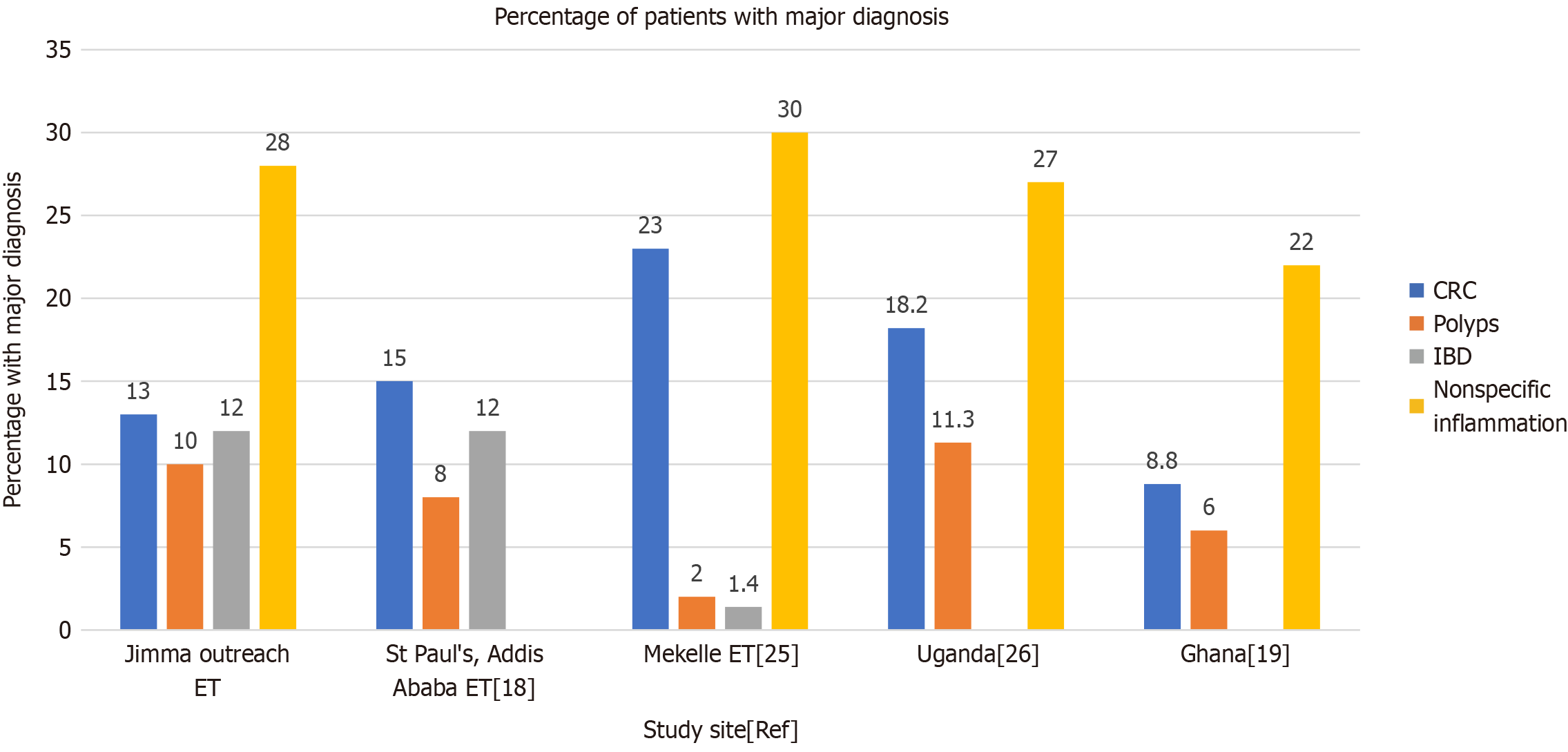

Although there are no community-based studies addressing the prevalence of CRC and polyps in Ethiopia, institution-based reports suggest that these neoplasms are prevalent among patients undergoing colonoscopy for symptom-based indications (15% CRC and 8% polyps in Addis Ababa, and 23% CRC in Mekelle, northern Ethiopia)[18,20]. A study from Ghana identified CRC in 8.8% and polyps in 6.0% while a similar report from Uganda indicated masses in 18.2% and polyps in 11.3% of all colonoscopy procedures (Figure 6)[19,21].

These findings suggest that colorectal neoplasms are common among patients with symptoms in African settings but are underdiagnosed and underreported[20]. As CRC is largely preventable through modifications of risk factors as well as the detection and removal of precancerous lesions via colonoscopic procedures, there is an urgent need to understand and address these issues to prevent future cases and deaths from the disease[23]. Population-based studies of prevalence of colorectal neoplasms and the implementation of targeted screening for high-risk and average-risk individuals along with early referral of symptomatic cases are recommended.

In major previous studies IBD has been considered uncommon in sub-Saharan Africa[27,28]. For instance, two systematic reviews published in 2020 identified fewer than 250 documented cases of IBD in the region (excluding South Africa), primarily consisting of case reports, case series, and small cohort studies; the largest cohort from Nigeria comprised only 32 patients. Major deficiencies in diagnostic and clinical capacity were noted, and this paucity of documented cases likely reflects underdiagnosis and underreporting[27,28].

In our experience the introduction of colonoscopy services in previously underserved regions along with the identification of IBD mucosal lesions and subsequent biopsy submissions has significantly heightened awareness of the condition among pathologists. This has resulted in a progressive increase in the number of patients with diagnosed IBD over 6 years: From 9 out of 93 cases (6.5%) in 2019 to a peak of 68 out of 412 cases (16.5%) in 2023. Another study from a referral hospital in Addis Ababa reported a similar prevalence of IBD at 12%, consistent with our findings[18]. Recent evidence also points to a rising incidence of IBD across sub-Saharan Africa[27,28]. These trends clearly indicate that IBD is not uncommon in sub-Saharan Africa but rather underdiagnosed and underreported due to limited diagnostic facilities and a lack of awareness among local practitioners.

One potential contributor to the increasing burden of IBD and colorectal neoplasms in Ethiopia is a notable improvement in the SDI over the past three decades, coupled with a transition from communicable to non-communicable diseases[29]. Similar transitions have been reported in other sub-Saharan African countries, with neoplastic and digestive diseases being among the conditions showing an increasing trend[12].

Taken together, the findings and observed trends likely reveal IBD and colorectal neoplasms as emerging public health burdens in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in Ethiopia. This underscores the urgent need for a realignment of educational, training, and policy focus from the traditional emphasis on communicable diseases to a balanced inclusion of these growing non-communicable public health concerns.

Strengths: The major strength of this study was the large-scale and sustained colonoscopic service provided to a rural population with very limited access to standard GI healthcare. The diagnostic yield of 83% is notably high. Nearly 60% of all patients had documented biopsy results, further ensuring the reliability of our diagnoses. The diverse patient population from a broad catchment area enhanced the generalizability of our findings. This research stands as the first comprehensive investigation of lower GI diseases in southwest Ethiopia, utilizing standard diagnostics such as colonoscopy and biopsy. We discovered that diseases typically regarded as rare in regions with low SDI are as common as simple infectious diseases and even more prevalent than hemorrhoids and diverticulosis. Local capacity building in terms of training nurses, creating awareness, and improving the diagnostic capacity of clinicians and pathologists was one significant impact of our project. This insight encourages practitioners to consider cancers, polyps, and IBD as common findings in the region, promoting timely referrals rather than repeated treatments for infectious conditions. Physicians were guided on management of the diagnosed conditions and recommended referral linkages for the major diseases that required specialist care.

Limitations: One potential limitation of our study was referral bias; patients with the most severe symptoms were more likely to be referred to our service and may skew our colonoscopic and histological findings. Additionally, some referred patients faced cultural, financial, or logistical barriers that hindered their access to our services, resulting in underrepresentation. These challenges may also help explain the lower proportion of female patients utilizing our service[30]. Furthermore, some of our rural patients may not receive optimal specialist care, medications for IBD maintenance therapy, or multidisciplinary team care for cancer due to a lack of gastroenterologists. Additionally, these medications are typically available only in hospitals located in large cities.

Challenges: The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic caused a forced service interruption for 6 months in 2019-2020. Further challenges included frequent power outages, unavailability of standard bowel preparation medications, inadequate bowel preparation among some patients, and a lack of local equipment maintenance, which may have affected the quality of our service.

Strengthening healthcare infrastructure: Local health authorities and institutions should prioritize investments in GI endoscopy services to improve diagnostic capabilities and patient care. This includes acquiring necessary equipment and training healthcare professionals in endoscopic procedures.

Targeted outreach programs: Implement community-based awareness initiatives aimed at educating the public about the symptoms and risks of lower GI diseases, particularly among females and younger populations who are disproportionately affected.

Policy advocacy: Engage policymakers to address barriers to equitable access to GI services, particularly for marginalized groups. This includes advocating for financial assistance programs and establishing mobile endoscopy units to reach underserved areas.

Research and data collection: Support ongoing research efforts to investigate the local factors contributing to the higher burden of CRC among females and younger individuals. Utilize findings to develop preventive strategies tailored to the specific needs of the community.

Collaboration and capacity building: Foster partnerships between local healthcare facilities and international organizations to facilitate training and capacity-building initiatives[11]. Sharing best practices from similar contexts can enhance service delivery and clinical outcomes.

There is a pressing need to address the significant gaps in colonoscopy services in Ethiopia and sub-Saharan Africa with an emphasis on ensuring equitable access for females and younger populations. Building local capacity in both human and material resources is essential for improving prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of major lower GI diseases. Our successful outreach colonoscopy service demonstrated that targeted efforts can effectively enhance patient care and provide critical evidence to inform local clinical practices, even in resource-limited settings.

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to the owner, staff, and management of Jimma Awetu Hospital for their commitment to investing in gastrointestinal endoscopy services. Their effective organization of numerous health institutions for patient referrals and collaboration with our gastroenterologist has been instrumental in the success of this large project. Special appreciation goes to the endoscopy nurses, whose dedication and tireless efforts—often working weekends and nights—have made a significant difference in the lives of our patients in need. We also express our sincere admiration for our patients, who demonstrated trust in us by embracing this newly introduced procedure, initially perceived as invasive. Additionally, we acknowledge the heads of departments and staff in Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology at Addis Ababa University for accommodating the travel schedules of our gastroenterologist during weekend duty rotations at the base institution.

| 1. | Bateman AC, Patel P. Lower gastrointestinal endoscopy: guidance on indications for biopsy. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2014;5:96-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bretthauer M, Løberg M, Wieszczy P, Kalager M, Emilsson L, Garborg K, Rupinski M, Dekker E, Spaander M, Bugajski M, Holme Ø, Zauber AG, Pilonis ND, Mroz A, Kuipers EJ, Shi J, Hernán MA, Adami HO, Regula J, Hoff G, Kaminski MF; NordICC Study Group. Effect of Colonoscopy Screening on Risks of Colorectal Cancer and Related Death. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1547-1556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 499] [Article Influence: 124.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Doubeni CA, Corley DA, Quinn VP, Jensen CD, Zauber AG, Goodman M, Johnson JR, Mehta SJ, Becerra TA, Zhao WK, Schottinger J, Doria-Rose VP, Levin TR, Weiss NS, Fletcher RH. Effectiveness of screening colonoscopy in reducing the risk of death from right and left colon cancer: a large community-based study. Gut. 2018;67:291-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 301] [Article Influence: 37.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Early DS, Ben-Menachem T, Decker GA, Evans JA, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Fukami N, Hwang JH, Jain R, Jue TL, Khan KM, Malpas PM, Maple JT, Sharaf RS, Dominitz JA, Cash BD. Appropriate use of GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:1127-1131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hong SM, Baek DH. A Review of Colonoscopy in Intestinal Diseases. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:1262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Issa IA, Noureddine M. Colorectal cancer screening: An updated review of the available options. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:5086-5096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 434] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 45.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (11)] |

| 7. | Kim SY, Kim HS, Park HJ. Adverse events related to colonoscopy: Global trends and future challenges. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:190-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 8. | Kothari ST, Huang RJ, Shaukat A, Agrawal D, Buxbaum JL, Abbas Fehmi SM, Fishman DS, Gurudu SR, Khashab MA, Jamil LH, Jue TL, Law JK, Lee JK, Naveed M, Qumseya BJ, Sawhney MS, Thosani N, Yang J, DeWitt JM, Wani S; ASGE Standards of Practice Committee Chair. ASGE review of adverse events in colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90:863-876.e33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gangwani MK, Aziz A, Dahiya DS, Nawras M, Aziz M, Inamdar S. History of colonoscopy and technological advances: a narrative review. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hong SW, Byeon JS. Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of early colorectal cancer. Intest Res. 2022;20:281-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bhat P, Hassan C, Desalegn H, Aabakken L. Promotion of gastrointestinal endoscopy in Sub-Saharan Africa: What is needed, and how can ESGE and WEO help? Endosc Int Open. 2021;9:E1001-E1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gouda HN, Charlson F, Sorsdahl K, Ahmadzada S, Ferrari AJ, Erskine H, Leung J, Santamauro D, Lund C, Aminde LN, Mayosi BM, Kengne AP, Harris M, Achoki T, Wiysonge CS, Stein DJ, Whiteford H. Burden of non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, 1990-2017: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e1375-e1387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 566] [Article Influence: 94.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hassan C, Aabakken L, Ebigbo A, Karstensen JG, Guy C, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Le Moine O, Vilmann P, Ponchon T. Partnership with African Countries: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) - Position Statement. Endosc Int Open. 2018;6:E1247-E1255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mwachiro M, Topazian HM, Kayamba V, Mulima G, Ogutu E, Erkie M, Lenga G, Mutie T, Mukhwana E, Desalegn H, Berhe R, Meshesha BR, Kaimila B, Kelly P, Fleischer D, Dawsey SM, Topazian MD. Gastrointestinal endoscopy capacity in Eastern Africa. Endosc Int Open. 2021;9:E1827-E1836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | World Health Organization. National Statistics Agency of Ethiopia. Population Estimates. 2023. Available from: https://data.who.int/countries/231. |

| 16. | Voss M, Forward LM, Smits CA, Duvenage R. Endoscopy outreach: how worthwhile is it? S Afr Med J. 2010;100:158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Audibert C, Perlaky A, Glass D. Global perspective on colonoscopy use for colorectal cancer screening: A multi-country survey of practicing colonoscopists. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2017;7:116-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gudissa FG, Alemu B, Gebremedhin S, Gudina EK, Desalegn H. Colonoscopy at a tertiary teaching hospital in Ethiopia: A five-year retrospective review. PAMJ-CM. 2021;5. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Brenu SG, Agbedinu K, Yorke J, Dally CK, Adinku MO, Micah E, Ayawin J, Oppong B, Adu-darko N, Okyere I, Mensah S, Boakye-yiadom J, Owusu PB, Ellis TF, Bonsu AS, Yorke DA, Buckman TA, Kwakye G, Laryea J. Enhancing Colonoscopy Services in Ghana: A Comprehensive Assessment of Referral Indications and Endoscopic Findings in a Leading Tertiary Care Hospital. J West Afr Coll Surg. 2025. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Kebede YM, Tsegay B, Abreha H. Endoscopic and Histopathological Correlation of Gastrointestinal Diseases in Ayder Referral Hospital, Mekelle University, Northern Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2017;55:285-291. |

| 21. | Din IH, Basimbe F, Kakande I. Colonoscopy Findings among Patients a Sub-Saharan Hospital: A 6-year Descriptive Cross-sectional Study. J Gen Prac. 2022;10:454. |

| 22. | Morgan E, Arnold M, Gini A, Lorenzoni V, Cabasag CJ, Laversanne M, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Murphy N, Bray F. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut. 2023;72:338-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 511] [Cited by in RCA: 1303] [Article Influence: 434.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (13)] |

| 23. | Douaiher J, Ravipati A, Grams B, Chowdhury S, Alatise O, Are C. Colorectal cancer-global burden, trends, and geographical variations. J Surg Oncol. 2017;115:619-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | González-Flores E, Garcia-Carbonero R, Élez E, Redondo-Cerezo E, Safont MJ, Vera García R. Gender and sex differences in colorectal cancer screening, diagnosis and treatment. Clin Transl Oncol. 2025;27:2825-2837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | White A, Ironmonger L, Steele RJC, Ormiston-Smith N, Crawford C, Seims A. A review of sex-related differences in colorectal cancer incidence, screening uptake, routes to diagnosis, cancer stage and survival in the UK. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 32.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tazinkeng NN, Pearlstein EF, Manda-Mapalo M, Adekunle AD, Monteiro JFG, Sawyer K, Egboh SC, Bains K, Chukwudike ES, Mohamed MF, Asante C, Ssempiira J, Asombang AW. Incidence and risk factors for colorectal cancer in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024;24:303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wang R, Li Z, Liu S, Zhang D. Global, regional and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e065186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 348] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 28. | Watermeyer G, Katsidzira L, Setshedi M, Devani S, Mudombi W, Kassianides C; Gastroenterology and Hepatology Association of sub-Saharan Africa (GHASSA). Inflammatory bowel disease in sub-Saharan Africa: epidemiology, risk factors, and challenges in diagnosis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:952-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | GBD 2019 Ethiopia Subnational-Level Disease Burden Initiative Collaborators. Progress in health among regions of Ethiopia, 1990-2019: a subnational country analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2022;399:1322-1335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Seidu AA. Mixed effects analysis of factors associated with barriers to accessing healthcare among women in sub-Saharan Africa: Insights from demographic and health surveys. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0241409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/