Published online Sep 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i9.109029

Revised: June 7, 2025

Accepted: August 20, 2025

Published online: September 16, 2025

Processing time: 137 Days and 9.8 Hours

Hepatobiliary and pancreatic cancers are often associated with high morbidity and mortality. Surgical intervention remains the cornerstone for curative treat

To evaluate the effectiveness of prehabilitation in patients undergoing hepatobiliary and pancreatic cancer resections.

Standard medical databases such as MEDLINE, EMBASE, PubMed, and Cochrane Library were searched to find randomised, controlled trials comparing prehabilitation vs no-prehabilitation before hepatic, biliary, or pancreatic cancer resections. All data were analysed using Review Manager Software 5.4, and the meta-analysis was performed with a random-effect model analysis.

A total of 8 studies were included (n = 568), recruiting adult patients undergoing hepatic, biliary, or pancreatic cancer resections. In the random effect model analysis, prehabilitation was associated with fewer postoperative complications compared to no prehabilitation [risk ratio (RR): 0.79, 95%CI: 0.66-0.95, Z = 2.52, P = 0.01]. No statistically significant difference was found in postoperative readmission rate (RR: 1.31, 95%CI: 0.79-2.17, Z = 1.05, P = 0.29), major complications (RR: 1.08; 95%CI: 0.61-1.92, Z = 0.28, P = 0.78), length of stay (standardised mean difference: -0.11, 95%CI: -0.31 to 0.1, Z = 1.05, P = 0.29), or mortality (RR: 0.28, 95%CI: 0.01-6.51, Z = 0.79, P = 0.43).

Prehabilitation was found to be effective in reducing postoperative complications following surgical intervention for hepatobiliary or pancreatic cancer.

Core Tip: Hepatobiliary and pancreatic cancer surgeries are complex procedures that carry a high risk of postoperative morbidity. This meta-analysis of 8 randomised controlled trials found that prehabilitation–focused on preparing patients physically, nutritionally, and mentally before surgery–significantly reduces the overall rate of complications. While no clear differences were seen in readmission, mortality, or length of stay, the data suggest a valuable role for prehabilitation in improving recovery following major abdominal cancer operations. These results highlight its potential for integration into standard preoperative care.

- Citation: Lubbad O, Mahmood WU, Shafique S, Singh KK, Khera G, Sajid MS. Effect of prehabilitation in patients undergoing hepatobiliary and pancreatic cancer resections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(9): 109029

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i9/109029.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i9.109029

Hepatobiliary and pancreatic cancers are among the most lethal malignancies worldwide. In 2020, liver and pancreas cancers alone accounted for 1623000 new cases and 1241000 deaths worldwide[1]. Surgical intervention is a cornerstone in the management of these cancers, often integrated into a multifaceted treatment approach that may include systemic therapies, radiation, and neoadjuvant strategies[2]. However, operations involving the liver, pancreas, and gallbladder are highly invasive procedures, with high mortality and morbidity rates[3]. These complex surgeries are associated with various postoperative complications, including, but not limited to, pancreatic fistulas, gastroparesis, intra-abdominal abscesses, and bile leakage[4,5]. Previous studies have demonstrated that pancreatic cancer patients who undergo surgical resection have a median survival of 27.1 months and a five-year survival rate of 34.5%[6]. Given the poor prognosis and high complication rate, patient care strategies that aim to improve postoperative recovery and outcomes must be developed.

Prehabilitation can be defined as a multifaceted strategy for optimizing patients preoperatively to withstand surgical stress[7]. It includes interventions targeting various aspects of a patient's overall health, such as nutrition, exercise capacity, and psychological well-being[7]. Currently, such interventions are more widely used postoperatively, with the example of the enhanced recovery after surgery program, which has been proven to shorten hospital stays after surgery[8]. Several studies have revealed a correlation between poor preoperative cardiopulmonary reserve and increased postoperative complications[7]. Prehabilitation has been shown to improve patient functional capacity leading up to surgery and reduce the incidence of severe postoperative complications[9]. Furthermore, patients tend to be more accepting of lifestyle interventions in the preoperative period, possibly improving adherence[10]. A previous meta-analysis has found that prehabilitation was linked with a trend towards fewer complications and shorter hospital stays, however, they were limited to their study selection, which included multiple non-randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and cohort studies[11]. This meta-analysis is the first to provide a comprehensive review of all RCTs available, comparing prehabilitation to no prehabilitation in patients undergoing surgery for hepatobiliary and pancreatic cancer.

This meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the preferred reporting items for a systematic review and meta-analysis, through the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses guidelines[12].

For this systematic review and meta-analysis, an electronic database search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, PubMed, and The Cochrane Library was conducted for RCTs. Articles published until January 2025 were searched for, using the Medical Subject Headings “prehabilitation liver cancer”, “prehabilitation pancreatic cancer”, and “prehabilitation hepatobiliary cancer”. Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) were used to refine the search results. The titles from the search results were independently reviewed by two authors and were determined to either be included or excluded from the study. The referenced list of the included studies was searched to find any additional articles. The accuracy of the extracted data was later confirmed by a third author.

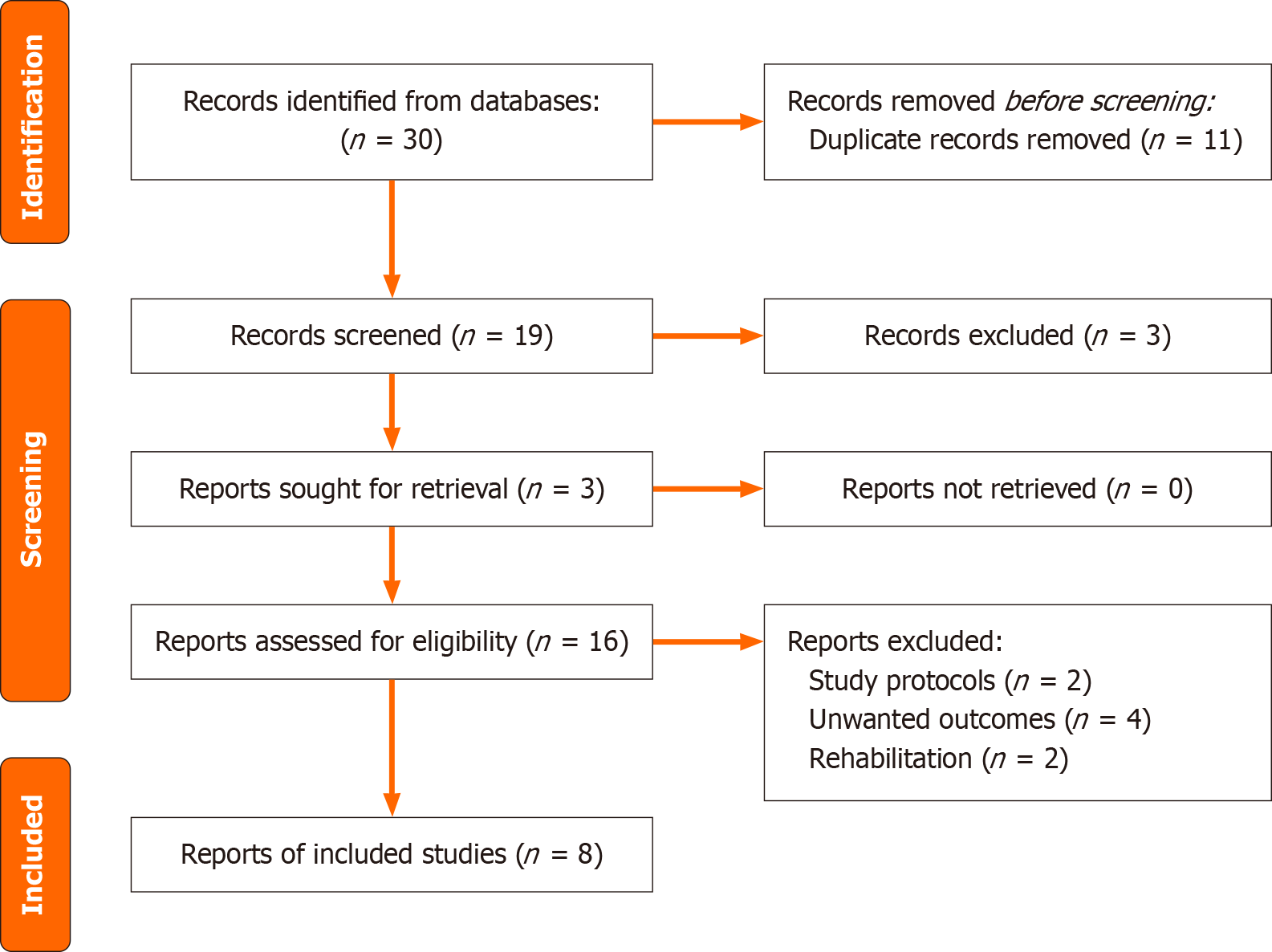

Only RCTs involving human participants directly comparing the effects of prehabilitation to no prehabilitation in hepatobiliary or pancreatic cancer patients awaiting surgery were chosen. We excluded quasi-experimental studies, cohort studies, and case-control studies. There was no restriction on the country of origin for the studies, language, or hospital of origin. The main outcomes we were searching for were postoperative complications, length of stay (LOS), readmissions, and mortality. The process and results of the literature retrieved are shown in Figure 1.

Data from included studies was extracted by two independent reviewers into a predefined meta-analysis form. A third reviewer confirmed the accuracy of the data. There were no discrepancies in trial selection or data extraction between the reviewers.

The software package Review Manager 5.4[13] by the Cochrane Collaboration was utilised for the statistical analysis. The risk ratio (RR) with a 95%CI was calculated for binary data, and the standardised mean difference (SMD) with a 95%CI was used for continuous data variables. The random effects model[14,15] was used to calculate the combined outcomes for dichotomous variables. Heterogeneity was explored through the χ2 test, with significance set at P < 0.05, and was quantified[16] using I2, with a maximum value of 30% signifying low heterogeneity. If the standard deviation was not available, it was calculated through the guidelines set out by the Cochrane Collaboration[17]. The Mantel-Haenszel method was used to calculate odds ratio under the random-effect model analysis[18]. Only RCTs that were clinically homogenous and had tested the same variables, such as 6-minute walking distance or LOS, were pooled together.

In a sensitivity analysis, 0.5 was added to each cell frequency for trials in which no event occurred in either the treatment or control group, according to the method recommended by Deeks et al[19]. This process assumed that both groups had the same variance, which may not have been confirmed, and variance was either estimated from the range or the P value. The estimate of the difference between both techniques was pooled, depending on the effect weights in the results determined by each trial’s estimated variance. Forest plots were used for graphical display. The square around the estimate stood for the accuracy of the estimation (sample size), and the horizontal line represented the 95%CI. The methodological quality of the included trials was initially assessed by the Cochrane trial quality assessment tool[17].

The primary database search led to thirty studies, of which twenty-two were excluded after initial screening. The final review included eight studies (Figure 1).

Eight RCTs on 568 patients were included in our updated comprehensive systematic review comparing patient outcomes between prehabilitation and no prehabilitation in patients undergoing surgical intervention in the form of resection for hepatobiliary or pancreatic cancer. Principles advised by the Cochrane Collaboration were used in this analysis. The trials included were studied in Spain, the United Kingdom, Canada, Denmark, Japan, and United States. Primary demographic characteristics of the studies included are specified in Table 1, and the protocol used in each study is given in Table 2[20-27].

| Ref. | Country | Operation | Number of recruited patients | Age in years | Female:male | Duration of follow up | Trial running time |

| Ausania et al[20], 2019 | Spain | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | |||||

| Prehabilitation | 18 | 66.1 ± 10.51 | 9:9 | ||||

| No prehabilitation | 22 | 65.7 ± 10.751 | 9:13 | 18 days | 2015-2017 | ||

| Dunne et al[21], 2016 | United Kingdom | Liver resection | |||||

| Prehabilitation | 20 | 61 ± 2.51 | 7:13 | 4 weeks | 2011-2013 | ||

| No prehabilitation | 17 | 62 ± 4.751 | 4:13 | ||||

| Gade et al[22], 2016 | Denmark | Pancreatic cancer resection | |||||

| Prehabilitation | 19 | 68 ± 7.751 | 7:12 | 30 days | 2012-2012 | ||

| No prehabilitation | 16 | 69 ± 6.51 | 10:6 | ||||

| Griffiths et al[23], 2024 | Canada | Open and laparoscopic hepatic, pancreatic, and colorectal resection | |||||

| Prehabilitation | 33 | 65 ± 3.251 | 12:21 | 12 weeks | Not reported | ||

| No prehabilitation | 30 | 63 ± 2.51 | 13:17 | ||||

| Kaibori et al[24], 2013 | Japan | Hepatectomy | |||||

| Prehabilitation | 25 | 68 ± 9.1 | 8:17 | 6 months | 2008-2010 | ||

| No prehabilitation | 26 | 71.3 ± 8.8 | 7:19 | ||||

| McIsaac et al[25], 2022 | Canada | Open and minimally invasive hepatobiliary, colorectal, thoracic, urologic cancer resections | |||||

| Prehabilitation | 94 | 74 ± 7 | 57:34 | 30 days | 2017-2019 | ||

| No prehabilitation | 88 | 74 ± 6 | 46:42 | ||||

| Mikkelsen et al[26], 2022 | Denmark | Pancreatic, biliary tract, non-small cell lung cancer resections | |||||

| Prehabilitation | 41 | 72.1 ± 1.81 | 22:19 | 13 weeks | 2018-2020 | ||

| No prehabilitation | 43 | 71.5 ± 1.71 | 26:17 | ||||

| Ngo-Huang et al[27], 2024 | United States | Pancreatic cancer resection | |||||

| Prehabilitation | 75 | 66.1 ± 8.5 | 26:49 | 3 months | 2017-2021 | ||

| No prehabilitation | 76 | 66.2 ± 8.2 | 33:43 |

| Ref. | Prehabilitation | No prehabilitation |

| Ausania et al[20], 2019 | 5 days training in outpatient clinic and daily training at home. Nutritional support. Endocrine and exocrine pancreatic management | Dietary advice, physical activity recommendations |

| Dunne et al[21], 2016 | 12 personalized exercise sessions over 4 weeks period | Standard care |

| Gade et al[22], 2016 | Oral supplement 7 days before surgery | No intervention |

| Griffiths et al[23], 2024 | Supplement solutions. 20 g protein isolate powder day 30-6 pre-operation. Immunonutrition 3 times a day 5-1. Carbohydrate rich solution night and morning of surgery | Placebo supplements, standard care |

| Kaibori et al[24], 2013 | Patient tailored exercise program. Dietary advice | Dietary advice |

| McIsaac et al[25], 2022 | Strength training. Aerobic exercise. Flexibility training | Received physical activity recommendations pamphlet |

| Mikkelsen et al[26], 2022 | Exercise (60 minutes sessions twice a week). Protein supplement after each session. Individualized walking program. 2 nurse led counseling sessions | No interventions |

| Ngo-Huang et al[27], 2024 | Aerobic and resistance training. Nutrition counseling | Recommended to stay active and given informational material |

The methodological quality of the included RCTs is shown in Table 3[20-27]. Randomisation was achieved through either block randomisation, computer generation, the Pocock-Simon minimisation method, envelopes, or was not reported. Concealment was reported in two studies.

| Ref. | Randomization technique | Power calculation | Blinding | Intention-to-treat | concealment | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Ausania et al[20], 2019 | Not reported | Yes | Single blind | Not reported | Not reported | Yes | Yes |

| Dunne et al[21], 2016 | Random number block | Not reported | Single blind | Not reported | Not reported | Yes | Yes |

| Gade et al[22], 2016 | Envelopes | Yes | Single blind | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Griffiths et al[23], 2024 | Computer generated | Not reported | Double blind | Not reported | Not reported | Yes | Yes |

| Kaibori et al[24], 2013 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Yes | Yes |

| McIsaac et al[25], 2022 | Computer generated | Yes | Double blind | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Mikkelsen et al[26], 2022 | REDCap application | Yes | Single blind | Not reported | Not reported | Yes | Yes |

| Ngo-Huang et al[27], 2024 | Pocock-Simon minimization method | Yes | No blinding | Not reported | Not reported | Yes | Yes |

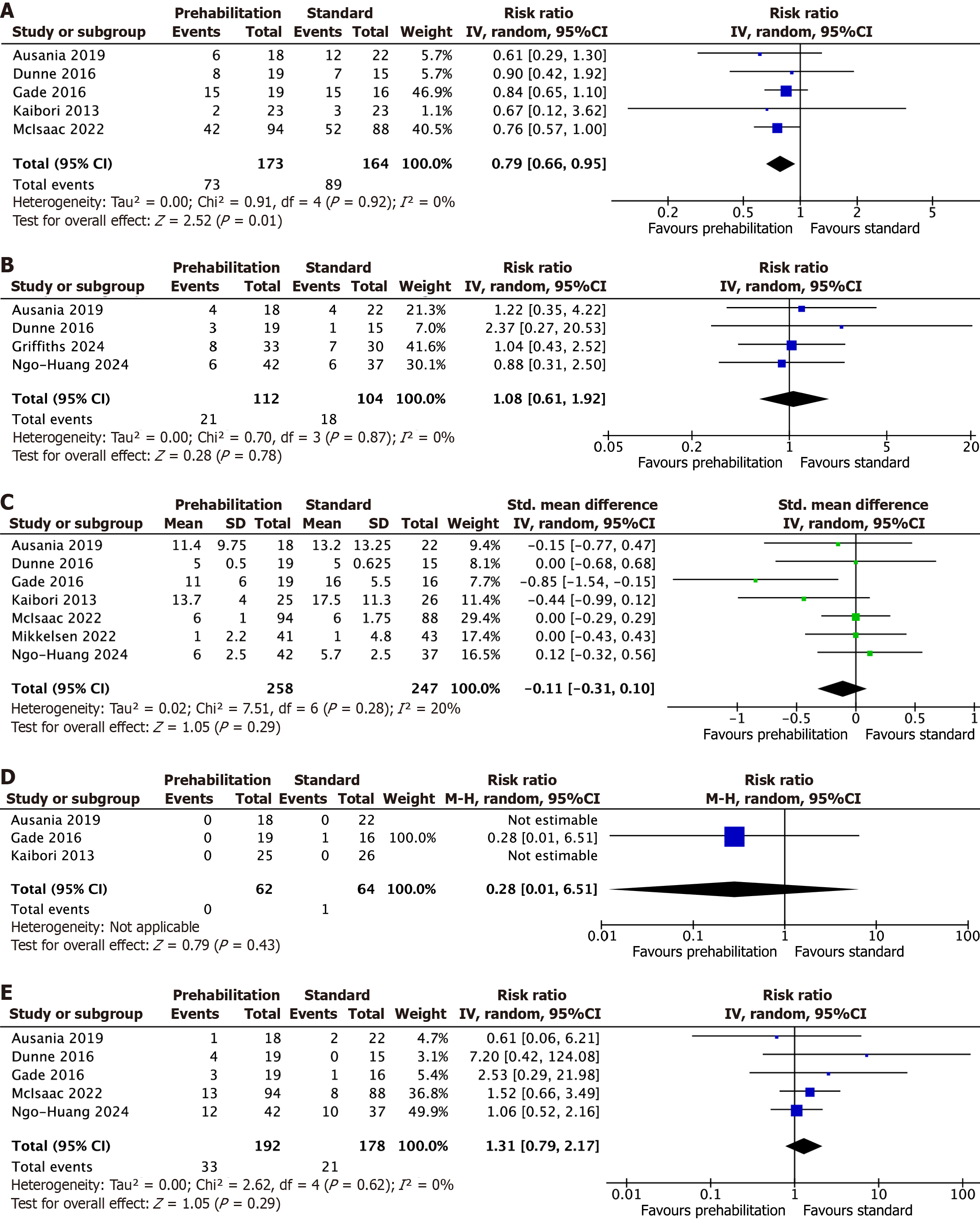

Total postoperative complications: A total of 5 studies on 337 patients undergoing open and laparoscopic surgery for hepatobiliary or pancreatic cancer reported total postoperative complications. The pooled analysis found that patients who underwent prehabilitation had significantly fewer postoperative complications (RR: 0.79, 95%CI: 0.66-0.95, Z = 2.52, P = 0.01). No statistically significant heterogeneity was observed among trials [Tau² = 0.00, χ2 = 0.91, df = 4 (P = 0.92), I² = 0%; Figure 2A][20-22,24,25].

A total of 4 studies on 216 patients undergoing open and laparoscopic surgery for hepatobiliary or pancreatic cancer reported the incidence of severe postoperative complications. The pooled analysis found no statistically significant difference between both groups (RR: 1.08, 95%CI: 0.61-1.92, Z = 0.28, P = 0.78). No statistically significant heterogeneity was observed among trials [Tau² = 0.00, χ2 = 0.70, df = 3 (P = 0.87), I² = 0%; Figure 2B][20,21,23,27].

A total of 7 studies on 505 patients undergoing open and laparoscopic surgery for hepatobiliary or pancreatic cancer reported the length of hospital stay. The pooled analysis found no statistically significant difference between both groups (SMD: -0.11, 95%CI: -0.31 to 0.1, Z = 1.05, P = 0.29). No statistically significant heterogeneity was observed among trials [Tau² = 0.02, χ2 = 7.51, df = 6 (P = 0.28), I² = 20%; Figure 2C][20-22,25-27].

A total of 5 studies on 370 patients undergoing open and laparoscopic surgery for hepatobiliary or pancreatic cancer reported postoperative readmission. The pooled analysis found no statistically significant difference between both groups (RR: 1.31, 95%CI: 0.79-2.17, Z = 1.05, P = 0.29). No statistically significant heterogeneity was observed among trials [Tau² = 0.00, χ2 = 2.62, df = 4 (P = 0.62), I² = 0%); Figure 2D][20-22,25,27].

A total of 3 studies on 126 patients undergoing open and laparoscopic surgery for hepatobiliary or pancreatic cancer reported mortality. The pooled analysis found no statistically significant difference between both groups (RR: 0.28, 95%CI: 0.01-6.51, Z = 0.79, P = 0.43; Figure 2E)[20,22,24]. Heterogeneity was not assessed due to the lack of mortality in trials, results should be interpreted with caution.

Eight RCTs with a combined total of 568 patients (291 who underwent prehabilitation and 277 who did not) were included in our systematic review and meta-analysis comparing outcomes of patients who received prehabilitation vs those who did not prior to surgical resection of hepatobiliary or pancreatic cancer. Our results suggest that prehabilitation could serve as an effective tool to decrease overall postoperative morbidity. Our findings revealed no significant difference between groups in the incidence of severe complications, LOS, readmission rates, and mortality. However, the paucity of RCTs and limited available high-quality evidence on the subject may undermine the validity and generalisability of the findings, potentially obscuring true effects that may exist across real-world populations.

Two similar previously published meta-analyses were identified: (1) Deprato et al[28] in 2022 titled “Surgical outcomes and quality of life following exercise-based prehabilitation for hepato-pancreatico-biliary surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis”; and (2) Lambert et al[29] in 2021 titled “The impact of prehabilitation on patient outcomes in hepatobiliary, colorectal, and upper gastrointestinal cancer surgery: A PRISMA-accordant meta-analysis”. These studies have discussed similar outcomes to the ones we reported, however, the reliability of their results is compromised by their study selection, including several non-RCTs. Our study was the first of its kind to include strictly all available RCTs on the matter, providing more thorough, high-quality evidence and improved insight into the effects of prehabilitation. It is important to note that both studies found significant reductions in postoperative LOS in prehabilitation groups. While our findings did reveal a trend towards shorter hospital stays, no statistically significant difference was observed. Moreover, both studies found no significant reduction in postoperative complications, whereas our analysis did. Such discrepancies may be attributed to variations in the prehabilitation protocols used across the studies, as well as differences in surgical complexity, patient populations, or postoperative care practices. Additionally, the relatively small sample size in some of the included studies may have limited the ability to detect a significant effect.

A review of the existing literature shows that this meta-analysis and systematic review is the most comprehensive and up-to-date review on the effect of prehabilitation on patients undergoing hepatobiliary or pancreatic cancer resections. However, several limitations exist that may undermine our findings. Firstly, due to our strict inclusion criteria of only RCTs, our analysed population sample was relatively small, which impedes our ability to draw generalised conclusions about real-world populations. Secondly, employed interventions significantly differed as prehabilitation was either multimodal, nutritional, or exercise-based. Furthermore, postoperative rehabilitative care also varied between included trials, introducing further heterogeneity across patient populations. Thirdly, studies included in our analysis had relatively short follow-up durations, meaning the long-term effects of prehabilitation are yet to be adequately explored. Fourthly, several included RCTs also enrolled patients undergoing surgical resection for other gastrointestinal cancers (e.g., colorectal), potentially skewing results and not reflecting real-world populations. Finally, as shown in Figure 2A[20,21,23-25], several methodological aspects, such as blinding and randomisation techniques, have not been reported, possibly introducing bias into respective trials. Further research should aim to address such gaps across the literature to provide valuable insight into the long-term effects of prehabilitation.

Prehabilitation may be a beneficial strategy to reduce postoperative complications and improve outcomes in patients undergoing surgery for hepatobiliary or pancreatic cancer. Despite these results, further research is required to draw generalised, long-term conclusions.

| 1. | Arnold M, Abnet CC, Neale RE, Vignat J, Giovannucci EL, McGlynn KA, Bray F. Global Burden of 5 Major Types of Gastrointestinal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:335-349.e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 857] [Cited by in RCA: 1437] [Article Influence: 239.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (15)] |

| 2. | Bardia A, Nisly NL, Zimmerman MB, Gryzlak BM, Wallace RB. Use of herbs among adults based on evidence-based indications: findings from the National Health Interview Survey. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:561-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hayashi K, Yokoyama Y, Nakajima H, Nagino M, Inoue T, Nagaya M, Hattori K, Kadono I, Ito S, Nishida Y. Preoperative 6-minute walk distance accurately predicts postoperative complications after operations for hepato-pancreato-biliary cancer. Surgery. 2017;161:525-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nakamura K, Akahori T, Sho M. Biliary complications after pancreatoduodenectomy. J Japan Pancreas Soc. 2019;34:150-156. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Lo CM, Fan ST, Liu CL, Lai EC, Wong J. Biliary complications after hepatic resection: risk factors, management, and outcome. Arch Surg. 1998;133:156-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Li Y, Zhao Q, Fan LQ, Wang LL, Tan BB, Leng YL, Liu Y, Wang D. Zinc finger protein 139 expression in gastric cancer and its clinical significance. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:18346-18353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gillis C, Ljungqvist O, Carli F. Prehabilitation, enhanced recovery after surgery, or both? A narrative review. Br J Anaesth. 2022;128:434-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 42.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Keane C, Savage S, McFarlane K, Seigne R, Robertson G, Eglinton T. Enhanced recovery after surgery versus conventional care in colonic and rectal surgery. ANZ J Surg. 2012;82:697-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chen J, Hong C, Chen R, Zhou M, Lin S. Prognostic impact of a 3-week multimodal prehabilitation program on frail elderly patients undergoing elective gastric cancer surgery: a randomized trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024;24:403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Molenaar CJ, van Rooijen SJ, Fokkenrood HJ, Roumen RM, Janssen L, Slooter GD. Prehabilitation versus no prehabilitation to improve functional capacity, reduce postoperative complications and improve quality of life in colorectal cancer surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;5:CD013259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dewulf M, Verrips M, Coolsen MME, Olde Damink SWM, Den Dulk M, Bongers BC, Dejong K, Bouwense SAW. The effect of prehabilitation on postoperative complications and postoperative hospital stay in hepatopancreatobiliary surgery a systematic review. HPB (Oxford). 2021;23:1299-1310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 51143] [Article Influence: 10228.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | RevMan 5 download|Cochrane Training. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/online-learning/core-software/revman/revman-5-download. |

| 14. | DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26739] [Cited by in RCA: 31166] [Article Influence: 779.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Demets DL. Methods for combining randomized clinical trials: strengths and limitations. Stat Med. 1987;6:341-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 854] [Cited by in RCA: 809] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539-1558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21630] [Cited by in RCA: 27003] [Article Influence: 1125.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions|Cochrane Training. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook. |

| 18. | Egger M, Smith GD, Altman DG. Systematic reviews in health care: Meta-analysis in context. 2nd ed. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, 2008. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Deeks JJ, Altman DG, Bradburn MJ. Statistical methods for examining heterogeneity and combining results from several studies in meta-analysis. In: Egger M, Smith GD, Altman DG, editors. Systematic reviews in health care: Meta-analysis in context. 2nd ed. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, 2008: 285-312. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Ausania F, Senra P, Meléndez R, Caballeiro R, Ouviña R, Casal-Núñez E. Prehabilitation in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2019;111:603-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dunne DF, Jack S, Jones RP, Jones L, Lythgoe DT, Malik HZ, Poston GJ, Palmer DH, Fenwick SW. Randomized clinical trial of prehabilitation before planned liver resection. Br J Surg. 2016;103:504-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gade J, Levring T, Hillingsø J, Hansen CP, Andersen JR. The Effect of Preoperative Oral Immunonutrition on Complications and Length of Hospital Stay After Elective Surgery for Pancreatic Cancer--A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutr Cancer. 2016;68:225-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Griffiths CD, D'Souza D, Rodriguez F, Park LJ, Serrano PE. Quality of life following perioperative optimization with nutritional supplements in patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery for cancer: A randomized, placebo-controlled feasibility clinical trial. J Surg Oncol. 2024;129:1289-1294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kaibori M, Ishizaki M, Matsui K, Nakatake R, Yoshiuchi S, Kimura Y, Kwon AH. Perioperative exercise for chronic liver injury patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing hepatectomy. Am J Surg. 2013;206:202-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | McIsaac DI, Hladkowicz E, Bryson GL, Forster AJ, Gagne S, Huang A, Lalu M, Lavallée LT, Moloo H, Nantel J, Power B, Scheede-Bergdahl C, van Walraven C, McCartney CJL, Taljaard M. Home-based prehabilitation with exercise to improve postoperative recovery for older adults with frailty having cancer surgery: the PREHAB randomised clinical trial. Br J Anaesth. 2022;129:41-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mikkelsen MK, Lund CM, Vinther A, Tolver A, Johansen JS, Chen I, Ragle AM, Zerahn B, Engell-Noerregaard L, Larsen FO, Theile S, Nielsen DL, Jarden M. Effects of a 12-Week Multimodal Exercise Intervention Among Older Patients with Advanced Cancer: Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Oncologist. 2022;27:67-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ngo-Huang AT, Parker NH, Xiao L, Schadler KL, Petzel MQB, Prakash LR, Kim MP, Tzeng CD, Lee JE, Ikoma N, Wolff RA, Javle MM, Koay EJ, Pant SD, Folloder JP, Wang X, Cotto AM, Ju YR, Garg N, Wang H, Bruera ED, Basen-Engquist KM, Katz MHG. Effects of a Pragmatic Home-based Exercise Program Concurrent With Neoadjuvant Therapy on Physical Function of Patients With Pancreatic Cancer: The PancFit Randomized Clinical Trial. Ann Surg. 2023;278:22-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Deprato A, Verhoeff K, Purich K, Kung JY, Bigam DL, Dajani KZ. Surgical outcomes and quality of life following exercise-based prehabilitation for hepato-pancreatico-biliary surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2022;21:207-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lambert JE, Hayes LD, Keegan TJ, Subar DA, Gaffney CJ. The Impact of Prehabilitation on Patient Outcomes in Hepatobiliary, Colorectal, and Upper Gastrointestinal Cancer Surgery: A PRISMA-Accordant Meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2021;274:70-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/