Published online Jul 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i7.108264

Revised: April 21, 2025

Accepted: June 17, 2025

Published online: July 16, 2025

Processing time: 90 Days and 12.9 Hours

Small-bowel disorders, including obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB), Crohn's disease, and tumors, require accurate diagnostic approaches for effective treatment. Video capsule endoscopy (VCE) and simple balloon enteroscopy (SBE) are widely used; however, each modality has limitations, particularly regarding therapeutic intervention and diagnostic yield.

To evaluate diagnostic yields of various modalities for small bowel bleeding, ana

A comprehensive search of four databases (PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Scopus) revealed over 600 citations related to the use of capsule endoscopy and balloon enteroscopy for diag

Analysis of seven moderate-to-high-quality retrospective studies revealed comparable overall detection rates for small bowel lesions between VCE and SBE. VCE demonstrated superior performance in detecting vascular lesions. Conversely, SBE exhibited a higher efficacy in detecting ulcerative lesions. The overall diagnostic yield varied across studies, with VCE showing a range of 32%–83% for small bowel bleeding, whereas SBE demonstrated a higher overall detection rate of 69.7% compared to 57.6% for VCE (P < 0.05). Notably, SBE showed superior performance in diagnosing Crohn's disease, with a detection rate of 35%, compared to 11.3% for VCE (P < 0.001). The diagnostic concordance between VCE and SBE was influenced by the lesion type. Strong agreement was observed for inflammatory lesions (κ = 0.82, 95%CI: 0.75-0.89), whereas moderate agreement was noted for tumors (κ = 0.61, 95%CI: 0.52-0.70) and angiectasias (κ = 0.58, 95%CI: 0.49-0.67). SBE demonstrated significant advantages in therapeutic interventions, particularly in overt bleeding. Patient tolerability was generally higher for VCE, with a completion rate of 95% (95%CI: 92%-98%), compared to 85% for SBE (95%CI: 80%-90%). However, the capsule retention rate for VCE was 1.4% (95%CI: 0.8%-2.0%), necessitating subsequent intervention.

VCE and SBE are complementary techniques for evaluating small intestinal disorders. Although VCE remains the initial test of choice for patients with stable OGIB, SBE should be considered in patients requiring therapeutic in

Core Tip: Video capsule endoscopy (VCE) and simple balloon enteroscopy (SBE) are complementary techniques for evaluating small intestinal disorders. VCE is preferred as an initial non-invasive diagnostic tool, while SBE excels in therapeutic interventions and histopathological confirmations. VCE shows superior performance in detecting vascular lesions, whereas SBE is more effective for ulcerative lesions and Crohn's disease. The choice between modalities depends on the suspected lesion type and need for intervention. Combining both techniques enhances diagnostic accuracy and patient management. Future research should focus on improving diagnostic concordance and refining interpretation of VCE findings to optimize the diagnostic pathway for small bowel disorders.

- Citation: Gadour E, Miutescu B, Okasha HH, Ghiuchici AM, AlQahtani MS. Diagnostic yield of video capsule endoscopy vs simple balloon enteroscopy in small intestinal disorders: A systematic review. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(7): 108264

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i7/108264.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i7.108264

Clinical literature investigating the gastrointestinal tract has extensively highlighted the challenges of clear imaging of the small bowel based on its length and complex anatomy[1]. This complexity and diagnostic challenges have led to the small bowel being referred to as a "black box," as described by Ma et al[1] In the past three decades, visualization and access to most of the small intestine has been impossible, presenting a critical challenge to gastroenterologists in diagnosing small intestinal diseases[2]. Standard endoscopy using conventional gastroscopes introduced in the 1980s can only reach the second and third portions of the duodenum[2]. Progress in the field over the years has given rise to advance enteroscopic procedures with the ability to reach the ligament of Treitz and approximately 80 cm beyond this ligament. Moreover, the advent of colonoscopy, which can reach 10–20 cm beyond the ileocecal valve, was a key invention during this period[3,4].

Despite these innovations, Manno et al[2] highlight the unsatisfactory outcomes associated with most non-surgical small intestine diagnostic and disease management techniques that warrant surgical intraoperative enteroscopy. The single balloon enteroscope (SBE) system by Olympus, Tokyo, developed in 2006 and commercially introduced in 2007, is an easier diagnostic tool than the double-balloon enteroscope (DBE)[2]. According to the Cleveland Clinic, balloon enteroscopy, which utilizes a long thin tube paired with either one or two balloons, a high-resolution camera, and other minute instruments at the tips, allows for the visualization and examination of the entire length of the small bowel[5].

Clinically, the SBE procedure is used to collect biopsies, suction, flush the gastrointestinal tract through the instrument channel, and several other therapeutic interventions described by Manno et al[2]. The efficacy of SBE has been reported in several studies since its integration into gastroenterological studies by Ohtsuka et al[6], who showed no complications when SBE was compared with DBE. Furthermore, the study highlighted the reduced complexity of the SBE procedure and its higher diagnostic yield than that of the DBE procedure[6]. Moreover, an analysis of 60 patients with suspected small bowel disease by Ramchandani et al[7] showed total enteroscopy in 50% of the cases with small bowel disease, ranging from gastrointestinal bleeding to chronic abdominal pain and malabsorption syndrome in 77%, 61%, and 63% of the cases, respectively[7].

Videocapsule endoscopy (VCE) is an alternative diagnostic tool for gastrointestinal tract diseases[8]. Despite the use of this diagnostic tool preceding the introduction of balloon-assisted enteroscopy, VCE has been associated with greater magnification and superior resolution than other endoscopic interventions for diagnosing abnormalities in the small intestine. Sidhu et al[9] articulated the limited ability of SBE to image up to 80–120 cm beyond the ligament of Treitz, which is a challenge that VCE can easily manage. Arnott and Lo[10] hypothesized that VCE is a superior imaging and diagnostic approach to radiographic techniques, based on its ability to detect mucosal-based disease and angiodysplasia. VCE employs an ingestible capsule/pill fitted with a high-resolution camera that captures images of the digestive tract as the capsule progresses. These images are wirelessly transmitted to a data receiver attached to the patient's waist, allowing healthcare professionals to closely examine the linings of the small intestine to detect anomalies[11].

Small bowel wall thickening is largely associated with several conditions, which may result from neoplastic, inflammatory, infectious, or ischemic conditions[12]. As a non-specific sign, wall thickening presents diagnostic challenges that require a careful and systematic approach to identify the underlying cause. Early and accurate diagnosis is crucial as it informs treatment decisions ranging from medical management of benign conditions to surgical intervention for malignancies. At the same time, VCE and SBE represent two of the most utilized small intestine imaging modalities. This non-invasive approach offers a comprehensive view of the small bowel, whereas SBE provides the opportunity for direct visualization, biopsy, and therapeutic intervention. Despite their complementary strengths, the optimal choice between these modalities remains a matter of ongoing debate, especially for small intestinal wall thickening.

This systematic review compared the diagnostic accuracy, safety, patient tolerability, and clinical outcomes of VCE and SBE in patients with small intestinal wall thickening. By analyzing the current evidence, it provides insights into the most effective diagnostic approach, helping clinicians make informed decisions tailored to individual patient needs.

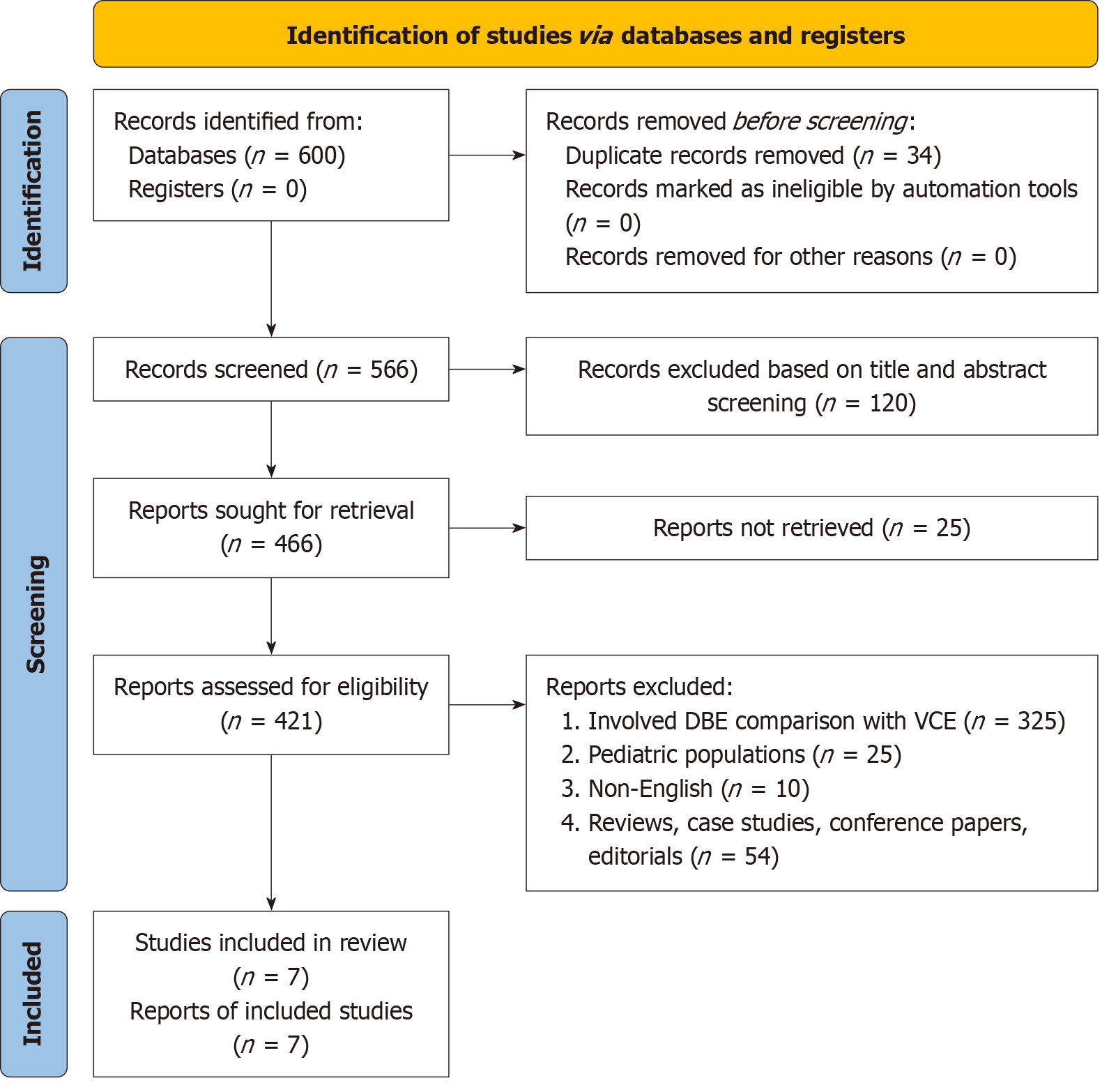

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using different medical databases to identify studies comparing the diagnostic utility of VCE and SBE in evaluating small intestinal wall thickening. A search was conducted across four electronic databases: PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Scopus. The search terms included a combination of MeSH terms and keywords such as: "small intestine wall thickening" AND "simple balloon enteroscopy" OR "balloon-assisted enteroscopy" AND "video capsule endoscopy" AND "small bowel imaging". No restrictions were placed on publication date to capture all relevant studies; however, the search was limited to articles published in English. In addition, the references from the identified articles were manually screened for relevant studies. This search was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

This systematic review employed the Population Intervention Comparison Study design and Outcomes. P: Population: Adult patients with suspected or confirmed small intestinal disorders, including obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB), Crohn's disease, and tumours; I: Intervention: Video capsule endoscopy (VCE); C: Comparison: SBE; O: Outcomes: Primary outcomes: Diagnostic yield, sensitivity and specificity, therapeutic utility; secondary outcomes: Safety (adverse events, complications), patient tolerability; clinical outcomes (treatment modification, patient management); S: Study design: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), prospective or retrospective cohort studies, and observational studies comparing VCE and SBE.

Studies included in the review met the following criteria: Population including adult patients aged ≥ 18 years with suspected or confirmed small intestinal wall thickening identified through imaging or clinical findings; intervention consisting of diagnostic assessment using VCE and/or SBE; studies comparing the diagnostic yield, accuracy, and clinical outcomes of VCE and SBE; primary outcomes including diagnostic yield, sensitivity, specificity, and therapeutic utility; secondary outcomes including safety (adverse events and complications), patient tolerability, and clinical outcomes (treatment modification and patient management); and RCTs, prospective or retrospective cohort studies, and observational studies.

Studies were excluded based on the following criteria: Pediatric populations (< 18 years); case reports, reviews, and editorial pieces without primary data; studies involving conditions unrelated to small intestine wall thickening (e.g., studies focusing on upper gastrointestinal bleeding without wall thickening); and articles not available in English.

Two independent reviewers screened titles, abstracts, and full texts to identify eligible studies. Disagreements were resolved by discussion or consultation with a third reviewer. The following data were extracted from each study: Study design and setting; patient characteristics (age, gender, underlying conditions); diagnostic yield of VCE and SBE for detecting specific pathologies (e.g., tumors, Crohn's disease, and vascular lesions); and rates of adverse events and complications (e.g., capsule retention for VCE and perforation for SBE).

The data analysis for this systematic review was qualitative, employing narrative synthesis, owing to the heterogeneity of the study designs and outcomes. The narrative synthesis approach allowed for a comprehensive comparison between VCE and SBE without quantitative pooling. The results were organized and interpreted by identifying the study patterns, themes, and relationships. Key elements, such as diagnostic yield, patient outcomes, safety, and clinical utility, were examined in detail, with conclusions drawn based on the collective findings of the included studies. This approach ensured a thorough and nuanced understanding of the relative benefits and limitations of each diagnostic modality in the context of small-intestinal wall thickening.

The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies tool. This tool evaluates the risk of bias across the following four domains: Patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing. Each study was rated as having a high, low, or unclear risk of bias.

An initial database search revealed 600 potential citations for inclusion in this review. A total of 34 duplicate studies were excluded after preliminary title scouring. In total, 166 studies proceeded to title and abstract screening, of which 120 were excluded based on their relevance to the study objectives. The resulting 446 studies were subjected to full-text retrieval, of which 25 could not be retrieved despite direct contact with their respective authors. The resulting 421 studies were subjected to full-text scouring based on the eligibility criteria by two independent researchers. Most studies (325) compared the outcomes of DBE and VCE. A total of 25 studies involved juvenile and pediatric populations, 10 studies were non-English and could not be accurately translated, and 54 studies were reviews, case studies, editorials, and conference papers. Thus, seven qualitative studies comparing the diagnostic outcomes of VCE and SBE were included in this review. The detailed literature search process is shown in Figure 1.

Table 1 details the findings and characteristics from the included studies. All the studies were of retrospective study design. The procedures assessed across all the studies were VCE and SBE[13-17].

| Ref. | Design | Total (n) | Included | Age | Modalities | Small bowel disorders identified | Findings | ||

| VCE | SBE | ||||||||

| Shiani et al[13] | Retrospective | 418 | 95 with OBGIB | 65.8 ± 12.2 | VCE and SBE | Vascular lesions | 39 | 30 | CE remains the preferred initial test for evaluating stable patients with OGIB, given its good concordance with key small bowel findings. However, in cases of severe overt small bowel bleeding, BAE may be a better first choice, as it allows for both diagnosis and immediate therapeutic intervention, avoiding delays in treatment. Future research should improve CE interpretation and enhance BAE's ability to comprehensively evaluate the entire small bowel for more effective management of OGIB cases |

| Active blood clots | 34 | 25 | |||||||

| Ulcer | 15 | 9 | |||||||

| Tumor/mass | 2 | 1 | |||||||

| Polyp | 6 | 7 | |||||||

| Ma et al[1] | Retrospective | 700 | 700 suspected small bowel diseases | 45.3 ± 15.1 | VCE and SBE | Diagnostic yield | No complications from the two procedures | ||

| VCE | SBE | VCE before SBE | |||||||

| 57.60% | 69.70% | 93.30% | |||||||

| Comparisons in findings | |||||||||

| Overall detection rate | 57.60% | 69.70% | |||||||

| Superficial ulcers and erosions | 42.40% | 45.10% | |||||||

| Crohn's disease | 11.30% | 35.00% | |||||||

| Bleeding | 2.20% | 0% | |||||||

| Parasites | 5.60% | 0.40% | |||||||

| Vere et al[14] | Retrospective | 29 | 21 patients | NR | VCE and SBE | Combined diagnosis of VCE and SBE | Combining VCE and SBE offers significant advancements in exploring the small bowel. However, histological examination remains the most definitive method for determining the exact nature of lesions | ||

| Inflammatory lesions | 23.80% | ||||||||

| Tumoral lesions | 52.38% | ||||||||

| Trifan et al[15] | Retrospective | 3 | 3 | 52 ± 11 | VCE and SBE | Adenocarcinomas | 33.30% | SBE is a safe and effective procedure that overcomes many limitations of VCE, especially regarding therapeutic intervention and histopathological confirmation. Both procedures are complementary in diagnosing suspected SBTs. VCE is recommended as the initial diagnostic tool due to its non-invasive nature, offering broad visualization of the small bowel. If abnormalities are detected, SBE should follow to confirm the diagnosis through histopathology and perform endoscopic therapy if necessary. This sequential approach optimizes both diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic outcomes | |

| Stromal tumors | 66.70% | ||||||||

| Cañadas Garrido et al[16] | Retrospective | 428 | 74 VCEs, 71 enteroscopy1 | 63.9 ± 13.5 | VCE and SBE/DBE | Diagnostic yield | Both VCE and enteroscopy had a comparable overall detection rate for small bowel lesions. However, the type of lesion significantly influenced diagnostic agreement. Although the agreement was stronger for inflammatory lesions, it was moderate for conditions like angiectasias and tumors. The results between the two methods differed in 38 patients (51.3%). Additionally, there was one case of complete capsule retention (1.4%), and active bleeding was identified in 13 patients (17.6%). This suggests that while both techniques are effective, the lesion type plays a critical role in shaping diagnostic outcomes | ||

| VCE | SBE1 | ||||||||

| 86.50% | 58.10% | ||||||||

| Ooka et al[17] | Retrospective | 194 | 103 VCE and 91 SBE | 67 ± 17 | VCE and SBE | Small bowel disorders identified | Both CE and SBE are valuable diagnostic tools for OGIB. However, for cases of overt or ongoing bleeding, SBE may be more suitable. This is because SBE allows for a precise endoscopic diagnosis and immediate therapeutic intervention, such as coagulation of bleeding lesions, during the same procedure. In contrast, while CE is effective for initial diagnosis and non-invasive exploration, it cannot provide real-time treatment, which can be crucial in active bleeding scenarios. Thus, SBE offers an advantage when simultaneous diagnosis and therapy are needed | ||

| VCE | SBE | ||||||||

| Vascular lesions | 34 | 34 | |||||||

| Ulcer | 10 | 28 | |||||||

| Tumor/mass | 3 | 2 | |||||||

| Diverticulum | 2 | 3 | |||||||

Table 2 summarizes the quality appraisals of the included studies for each domain.

| Ref. | Consecutive/random sample | Case-control design | Avoided inappropriate exclusions | Avoided patient selection bias | Index test interpretation bias | Reference standard classification | Patient flow bias |

| Shiani et al[13] | Yes | Yes | Low | Low | Yes | Low | Yes |

| Ma et al[1] | Unclear | Yes | Moderate | Low | No | Low | Yes |

| Vere et al[14] | Unclear | No | High | Low | Yes | Low | No |

| Trifan et al[15] | Yes | Yes | Low | Low | Yes | Low | Yes |

| Cañadas Garrido et al[16] | Yes | Yes | Low | Low | Yes | Low | Yes |

| Ooka et al[17] | Yes | Yes | Low | Low | Yes | Low | Yes |

The studies analyzed documented various types of lesions in the small intestine, including vascular, ulcerative, inflammatory, and neoplastic lesions. Vascular lesions such as angiodysplasias were commonly reported, with VCE showing superior detection rates compared to SBE in some studies. Ulcerative lesions were also frequently evaluated, with SBE demonstrating better detection rates in certain cases. Inflammatory lesions, particularly those associated with Crohn's disease, were assessed across multiple studies. Neoplastic lesions like stromal tumors were identified in some analyses, with SBE showing efficacy in detecting these more complex pathologies. Additionally, active bleeding sites and blood clots were documented. While less common, some studies also noted infectious processes. The extent of lesion categorization varied between studies, but generally encompassed a wide range of pathologies relevant to small bowel disorders.

This systematic review analyzed a range of studies comparing VCE and SBE for the diagnosis of small-bowel disorders, with a focus on OGIB and other pathologies. Among the included studies, VCE was frequently used as the initial diagnostic tool because of its non-invasive nature[18]. At the same time, SBE played a pivotal role in therapeutic interventions and histopathological confirmations.

The results indicated that both modalities have strengths and limitations. Shiani et al[13] reported that VCE identified a higher number of vascular lesions (39 cases) than that identified by SBE (30 cases); however, the detection rates for active blood clots and ulcers were similar. Ma et al[1] demonstrated that SBE had a higher overall detection rate (69.7%) than that of VCE (57.6%), particularly for Crohn's Disease (35% vs 11.3%), an observation that supports the use of VCE for initial diagnosis in accordance with Li et al[19], followed by SBE for further exploration and treatment. Several studies have reported a moderate-to-low diagnostic yield of VCE (32%-83%) for small bowel bleeding[20,21]. Vere et al[14] highlighted the utility of combining both techniques, especially for identifying tumor lesions (52.38%). Nonetheless, Sethi et al[22] promoted the superiority of enteroscopy in terms of diagnostic yield when performed after VCE compared with enteroscopy alone (68.2% vs 43.8%).

In more specific cases, such as those studied by Trifan et al[15], SBE demonstrated a superior diagnostic yield for stromal tumors, indicating its efficacy in identifying more complex pathologies. Cañadas Garrido et al[16] observed comparable detection rates between the two methods, although VCE had a higher yield of inflammatory lesions. Notably, Ooka et al[17] indicated that while VCE and SBE were equally effective in identifying vascular lesions, SBE had better detection rates for ulcers (28 vs 10 cases) and was able to provide immediate treatment in active bleeding scenarios. Iddan et al[23] recommended that the incidence of massive lesions, specifically neoplastic lesions, should be further confirmed prior to VCE and SBE using computed tomography whenever possible.

Overall, this review highlights the complementary nature of VCE and SBE in the diagnostic pathway of small-bowel disorders. VCE remains a key first-line tool because of its ability to provide broad non-invasive visualization, whereas SBE is invaluable for cases requiring therapeutic intervention and more detailed exploration. Overall, the findings suggest that the lesion type is a significant factor influencing the choice of modality, with SBE being preferable in cases where therapeutic actions are anticipated. Future research should focus on refining the diagnostic concordance between these modalities and improving the interpretation of the VCE findings.

The primary limitation of this systematic review stems from the limited number of studies that directly compare VCE with SBE for small bowel disorders. The available data are largely retrospective, and few studies have provided head-to-head comparisons across a wide range of patient demographics and disease categories. Additionally, the sample sizes in several studies, such as those by Vere et al[14] and Trifan et al[15], were relatively small, which may have affected the generalizability of the findings. Another limitation is the variability in the diagnostic criteria and methodologies used across the studies, including differences in patient selection and types of lesions being examined.

Furthermore, most included studies focused on a specific subset of small bowel disorders such as OGIB or Crohn's disease, limiting the ability to generalize the findings to other small bowel pathologies. Finally, although histology is emphasized as the gold standard for diagnosis, not all studies provided data on histopathological confirmation, which may have affected the interpretation of the diagnostic yield between VCE and SBE. Future research with larger pro

Emerging technologies, such as Narrow-Band Imaging (NBI), hold promise in enhancing the diagnostic capabilities of both VCE and SBE. NBI improves the visualization of vascular patterns and mucosal structures, potentially increasing the detection rates of subtle lesions that may otherwise be overlooked. By integrating NBI with existing endoscopic tech

Future research should aim to enhance our understanding of small bowel bleeding diagnostics through several key initiatives. Conducting sensitivity analyses to evaluate the impact of study quality and methodological differences on diagnostic yields is crucial. Exploring factors contributing to heterogeneity, such as patient demographics, clinical characteristics, timing of diagnostic procedures, definition and classification of small bowel bleeding, expertise of endoscopists and radiologists, and technical specifications of imaging modalities, will provide valuable insights. Standardizing the reporting of diagnostic yields and outcome measures is essential to facilitate more robust meta-analyses and subgroup comparisons in future systematic reviews. Additionally, investigating the impact of newer technologies and improved imaging techniques on diagnostic yields will help advance the field. Evaluating long-term clinical outcomes associated with different diagnostic approaches is necessary to better understand their relative effectiveness in managing small bowel bleeding. These research directions will contribute to improving diagnostic accuracy, optimizing patient care, and refining clinical guidelines for small bowel bleeding management.

Both VCE and SBE play critical roles in the diagnosis of small bowel disorders, particularly in cases of OGIB. VCE serves as a non-invasive and effective first-line tool, providing broad visualization of the small bowel. However, SBE offers sig

| 1. | Ma JJ, Wang Y, Xu XM, Su JW, Jiang WY, Jiang JX, Lin L, Zhang DQ, Ding J, Chen L, Jiang T, Xu YH, Tao G, Zhang HJ. Capsule endoscopy and single-balloon enteroscopy in small bowel diseases: Competing or complementary? World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:10625-10630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Manno M, Barbera C, Bertani H, Manta R, Mirante VG, Dabizzi E, Caruso A, Pigo F, Olivetti G, Conigliaro R. Single balloon enteroscopy: Technical aspects and clinical applications. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4:28-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Stauffer CM, Pfeifer C. Colonoscopy. 2023 Jul 24. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2025. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Foutch PG, Sawyer R, Sanowski RA. Push-enteroscopy for diagnosis of patients with gastrointestinal bleeding of obscure origin. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:337-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Balloon-assisted enteroscopy: definition, process and recovery. Cleveland Clinic. Available from: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diagnostics/24199-balloon-assisted-enteroscopy. |

| 6. | Ohtsuka K, Kashida H, Kodama K, Ukegawa J, Kanie H, Mizuno K, Kudo Y, Takemura O, Kudo S. Observation and Treatment of Small Bowel Diseases Using Single Balloon Endoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:AB271. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Ramchandani M, Reddy DN, Gupta R, Lakhtakia S, Tandan M, Rao GV, Darisetty S. Diagnostic yield and therapeutic impact of single-balloon enteroscopy: series of 106 cases. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1631-1638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pennazio M, Rondonotti E, Despott EJ, Dray X, Keuchel M, Moreels T, Sanders DS, Spada C, Carretero C, Cortegoso Valdivia P, Elli L, Fuccio L, Gonzalez Suarez B, Koulaouzidis A, Kunovsky L, McNamara D, Neumann H, Perez-Cuadrado-Martinez E, Perez-Cuadrado-Robles E, Piccirelli S, Rosa B, Saurin JC, Sidhu R, Tacheci I, Vlachou E, Triantafyllou K. Small-bowel capsule endoscopy and device-assisted enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel disorders: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2022. Endoscopy. 2023;55:58-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 65.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sidhu R, Sanders DS, McAlindon ME. Gastrointestinal capsule endoscopy: from tertiary centres to primary care. BMJ. 2006;332:528-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Arnott ID, Lo SK. The clinical utility of wireless capsule endoscopy. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:893-901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Video capsule endoscopy: prep and results. City of Hope. 2021. Available from: https://www.cancercenter.com/diagnosing-cancer/diagnostic-procedures/video-capsule-endoscopy. |

| 12. | Macari M, Balthazar EJ. CT of bowel wall thickening: significance and pitfalls of interpretation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:1105-1116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Shiani A, Nieves J, Lipka S, Patel B, Kumar A, Brady P. Degree of concordance between single balloon enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after an initial positive capsule endoscopy finding. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2016;9:13-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vere CC, Foarfă C, Streba CT, Cazacu S, Pârvu D, Ciurea T. Videocapsule endoscopy and single balloon enteroscopy: novel diagnostic techniques in small bowel pathology. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2009;50:467-474. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Trifan A, Singeap AM, Cojocariu C, Sfarti C, Tarcoveanu E, Georgescu S. Single-balloon enteroscopy following videocapsule endoscopy for diagnosis of small bowel tumors: preliminary experiences. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2010;105:211-217. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Cañadas Garrido R, Rincón Sánchez R, Costa Barney V, Roa Ballestas P, Espinosa Martínez C, Pinzón Arenas D, Ramírez Barranco R. Diagnostic agreement between video capsule endoscopy and single and double balloon enteroscopy for small bowel bleeding at a tertiary care hospital in Bogota, Colombia. Revista de Gastroenterología de México (English Edition). 2021;86:51-58. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ooka S, Kobayashi K, Kawagishi K, Kodo M, Yokoyama K, Sada M, Tanabe S, Koizumi W. Roles of Capsule Endoscopy and Single-Balloon Enteroscopy in Diagnosing Unexplained Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Clin Endosc. 2016;49:56-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mylonaki M, Fritscher-Ravens A, Swain P. Wireless capsule endoscopy: a comparison with push enteroscopy in patients with gastroscopy and colonoscopy negative gastrointestinal bleeding. Gut. 2003;52:1122-1126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 342] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Li X, Chen H, Dai J, Gao Y, Ge Z. Predictive role of capsule endoscopy on the insertion route of double-balloon enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2009;41:762-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Concha R, Amaro R, Barkin JS. Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: diagnostic and therapeutic approach. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:242-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Carey EJ, Fleischer DE. Investigation of the small bowel in gastrointestinal bleeding--enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:719-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sethi S, Cohen J, Thaker AM, Garud S, Sawhney MS, Chuttani R, Pleskow DK, Falchuk K, Berzin TM. Prior capsule endoscopy improves the diagnostic and therapeutic yield of single-balloon enteroscopy. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:2497-2502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Iddan G, Meron G, Glukhovsky A, Swain P. Wireless capsule endoscopy. Nature. 2000;405:417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1994] [Cited by in RCA: 1410] [Article Influence: 54.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/