Published online Dec 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i12.114836

Revised: October 18, 2025

Accepted: November 13, 2025

Published online: December 16, 2025

Processing time: 78 Days and 3 Hours

Acquired hemophilia A (AHA) is a rare blood disorder that can cause life-threat

We report the case of a 76-year-old Japanese woman with AHA who presented with repeated bleeding from an esophageal ulcer as the initial symptom. A hemorrhagic ulcer was detected in the lower esophagus, and endoscopic hemo

Multidisciplinary interventions between endoscopists and hematologists are essential to manage rare gast

Core Tip: Acquired hemophilia A can cause life-threatening, severe bleeding. Most cases are characterized by subcutaneous or intramuscular bleeding, whereas gastrointestinal hemorrhage is rare. We report the case of a 76-year-old woman with AHA who presented with repeated bleeding from an esophageal ulcer. Endoscopic hemostasis using radiofrequency ablation was performed seven times; however, this procedure was unsuccessful. First, a mixture of factors VIIa and X (a bypass hemostatic agent) was administered, successfully controlling the hemorrhage from the esophageal ulcer. In addition, emicizumab (a substitute for activated factor VIII) was administered, after which no further bleeding was observed.

- Citation: Saito M, Miyashita K, Ieko M, Yokoyama E, Kanaya M, Izumiyama K, Mori A, Morioka M, Kondo T. Repeated hemorrhagic ulcers of the esophagus associated with acquired hemophilia A: A case report. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(12): 114836

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i12/114836.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i12.114836

Acquired hemophilia A (AHA) is a rare autoimmune bleeding disorder with a reported incidence of approximately 1.48 patients per million people per year[1]. AHA is caused by a marked decrease in coagulation factor VIII activity due to the development of autoantibodies (inhibitors) against factor VIII[2]. AHA is common among elderly individuals, with more than 80% of cases reported in those aged 60 years or older[1,3]. Although rare, gastrointestinal bleeding has also been reported[4-6].

Here, we report a case of AHA in which the initial symptom was an esophageal ulcer with repeated bleeding. This case highlights the diagnostic challenges and the need for a multidisciplinary approach in managing gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with AHA.

A 76-year-old Japanese woman presented with upper abdominal discomfort and loss of appetite. After passing black stools, she was unable to move and was admitted to a nearby hospital.

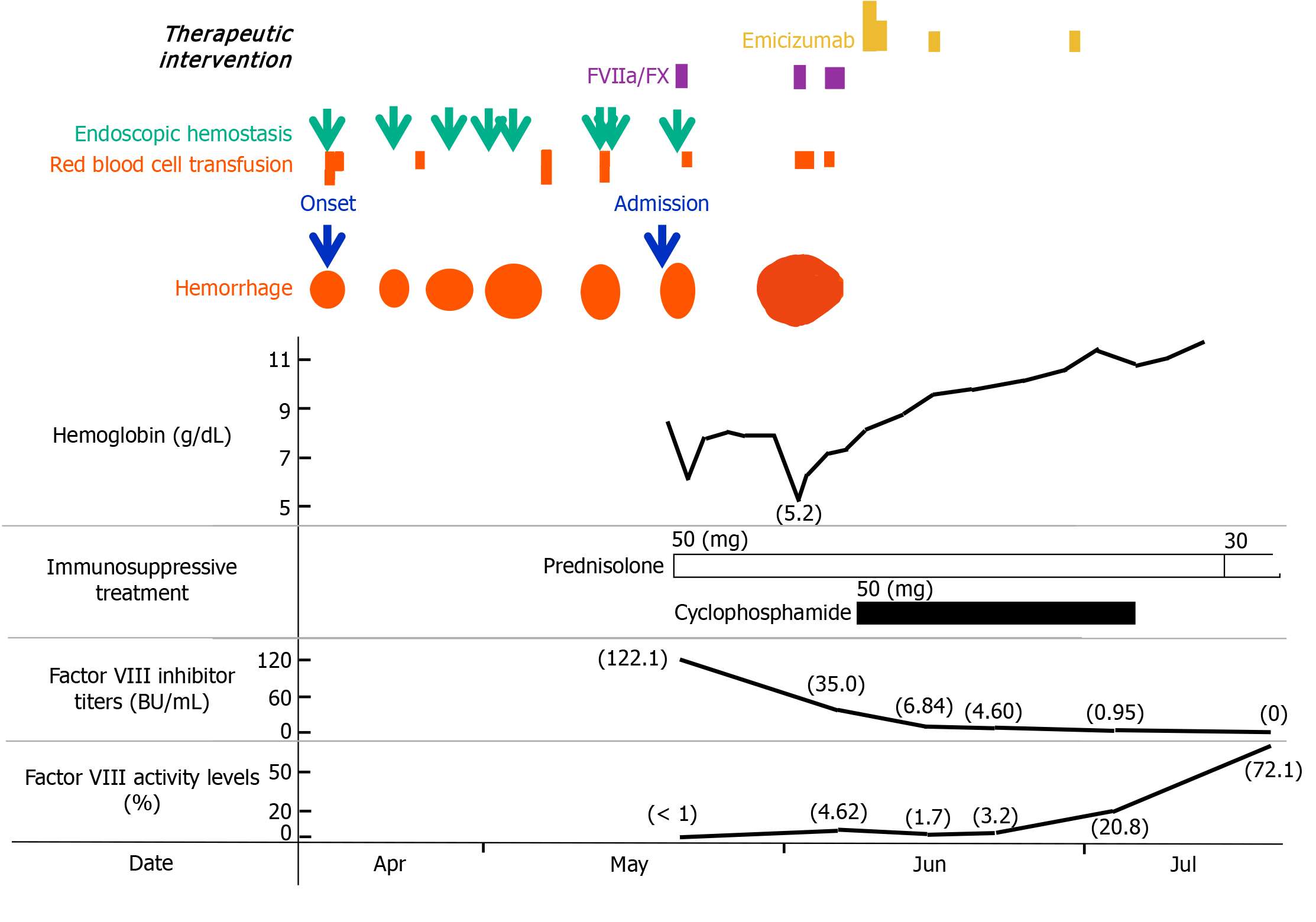

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed a bleeding ulcerative lesion in the lower esophagus. Radiofrequency ablation, the first choice for endoscopic hemostasis at this institution, was performed and was temporarily successful. However, bleeding recurred from the same lesion a few days later, and the same hemostatic procedure was repeated seven times for one month (Figure 1). PureStat® (an absorbable local hemostatic material derived from peptides) was also used once. The difficulty in stopping the bleeding was thought to be due to the fact that the ulcer lesion was located within the hiatal hernia, which was difficult to heal and that the patient had not stopped consuming food and taking cilostazol. Moreover, the true cause, which was the presence of a blood coagulation disorder since admission, was underestimated. During this time, a total of eight units of red blood cells were transfused. In addition, oozing of blood was observed at the insertion site of a peripherally inserted central venous catheter, and the attending physician reported to the hematologist that the activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), which had been mildly prolonged since admission (48.4 seconds), was further prolonged to 98.8 seconds eight days later. AHA was suspected, and the patient was transferred to our hospital.

The patient had a history of cerebral infarction and had been receiving outpatient treatment for hypertension and dyslipidemia.

The patient had not experienced any particular bleeding tendency until this time, and no relevant family history was reported.

The patient had subcutaneous hemorrhage in the left upper limb and anemia in the palpebral conjunctiva, but no particular abdominal abnormalities were noted.

The patient’s laboratory results on admission are shown in Table 1. The APTT was prolonged to 87.4 seconds, and the APTT cross-mixing test revealed a typical inhibitor pattern. The factor VIII inhibitor concentration was 122.1 BU/mL, and the factor VIII activity was < 1%.

| Laboratory examinations | Results |

| Peripheral blood | |

| WBC (4000-8000)/μL | 5900 |

| Neutrophils (45-74), % | 88 |

| Lymphocytes (20-45), % | 5 |

| Monocytes (2-8), % | 5 |

| Eosinophils (0-6), % | 1 |

| Basophils (0-3), % | 1 |

| RBC (380 × 104-500 × 104)/μL | 284 × 104 |

| Hemoglobin (12.0-16.0), g/dL | 8.4 |

| Plt (12.0 × 104-40.0 × 104)/μL | 32.4 × 104 |

| Coagulation system | |

| PT-INR (0.85-1.15) | 0.93 |

| APTT (23.0-35.0), seconds | 87.4 |

| Fib (200-400), mg/dL | 494 |

| FDP (< 5.0) | 6.4 MIC/mL |

| Serology | |

| CRP (< 0.3) | (1+) 0.38 mg/dL |

| FVIII inhibitor (-) | 122.1 BU/mL |

| FVIII activity (60-150), % | < 1 |

| Lupus anticoagulant (< 1.2) | 0.8 |

| Von Willebrand factor (60-170), % | 350 |

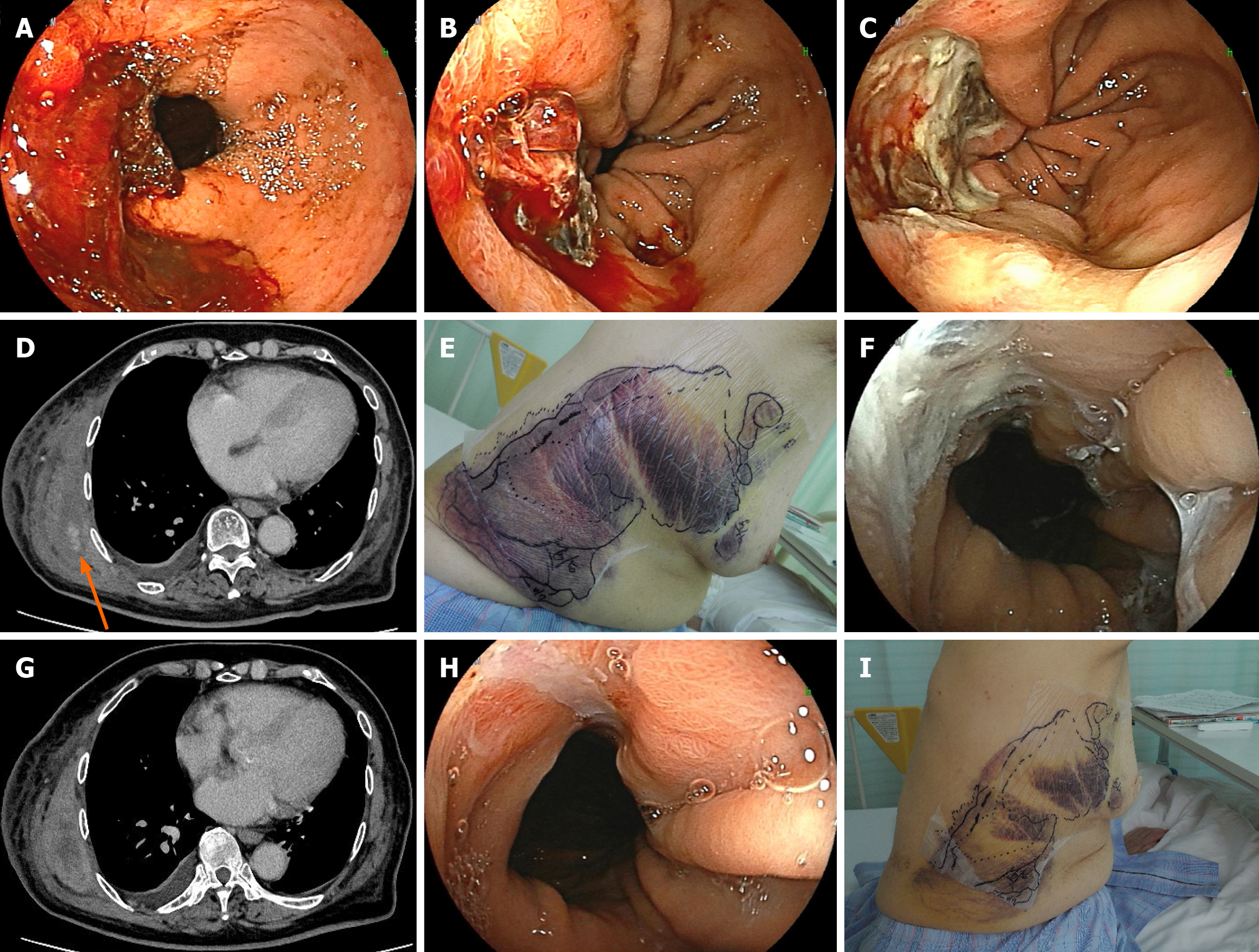

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy was also performed at our hospital, and the patient experienced bleeding from an ulcer in the lower esophagus (a hiatal hernia; Figure 2A).

Because gastrointestinal bleeding persisted despite repeated endoscopic treatments, a bleeding disorder was suspected, coagulation tests were performed again, and a hematologist was consulted.

On the basis of the aforementioned findings, this patient was diagnosed with a hemorrhagic esophageal ulcer comp

Prednisolone was started immediately (50 mg; 1 mg/kg/day), and endoscopic hemostasis using hypertonic saline-epinephrine injection plus clipping was performed (Figure 2B). New bleeding occurred from the clipped area, which was difficult to control and responded poorly to treatment. One unit of red blood cell transfusion was administered. A single administration of a bypass hemostatic agent, a mixture of factors VIIa and X (Byclot®), resulted in complete hemostasis (Figure 2C).

No further bleeding was observed from the same area; however, approximately two weeks later, an intramuscular hematoma was detected in the right chest muscles on computed tomography (Figure 2D), and adjacent subcutaneous bleeding had also expanded (Figure 2E). At this time, the esophageal ulcer remained hemostatic (Figure 2F). Her hemoglobin concentration rapidly decreased from 7.8 g/dL to 5.2 g/dL. Repeated red blood cell transfusions (a total of three units) and administration of a mixture of factors VIIa and X (three doses; Byclot®) successfully stopped the bleeding (Figure 2G). The patient had experienced repeated severe bleeding, had a high inhibitor concentration of 35.0 BU/mL at this point, and had factor VIII activity that was still less than 5%. To eliminate the inhibitor more quickly, cyclophosphamide (50 mg) was administered in combination with prednisolone. Moreover, because there was a high risk of rebleeding for at least the next month, emicizumab was administered to prevent recurrent bleeding. One week after emicizumab administration, the esophageal ulcer showed a marked tendency to heal (Figure 2H). The subcutaneous bleeding also began to subside (Figure 2I), and the bleeding tendency resolved completely.

Two months after the treatment, the factor VIII inhibitor disappeared. Now, more than two years later, the patient has maintained AHA remission and is living a healthy life.

AHA, a rare autoimmune disease, is believed to be caused by age-related immune dysregulation[7], and half of patients with AHA frequently have underlying malignancies or other autoimmune diseases[1,3]. Although our patient had a history of cerebral infarction, no underlying disease or medication was identified as the cause of AHA. A patient with congenital hemophilia A presenting with recurrent bleeding from esophageal ulcers as the initial symptom, similar to our case, has been reported previously[8]; however, to our knowledge, this is the first report of such a case in AHA. Huang et al[4] reported gastrointestinal hemorrhage as a bleeding episode associated with AHA in only one of 50 patients (2%), and Tanaka et al[5] reported its occurrence in 8% of 55 patients with AHA in Japan, which is a considerably lower incidence than that of subcutaneous or intramuscular hemorrhage. Furthermore, as reported by Abe et al[9] and even with our experience with the present case, gastrointestinal bleeding in AHA patients generally fail to resolve even after multiple endoscopic hemostasis or transcatheter arterial embolization procedures, thereby increasing the risk of recurrent bleeding. Therefore, controlling AHA-induced gastrointestinal bleeding requires not only local hemostasis by an endoscopist but also hemostatic treatment by a hematologist. Moreover, cooperation between the two practitioners is essential. Furthermore, if bleeding cannot be controlled by endoscopic procedures, gastrointestinal endoscopists must consider the possibility of some type of bleeding disorder, and if abnormal values are observed for APTT prolongation alone (platelet count, prothrombin time, and fibrinogen are normal), they should investigate the possibility of AHA.

Previously, hemostatic treatment for AHA focused on controlling acute bleeding through the on-demand use of bypass agents[3]. Recombinant FVIIa and activated prothrombin complex concentrates are commonly used internationally as bypass hemostatic agents[1,3]. In addition, a 1:10 combination of plasma-derived factor VIIa and factor X (Byclot®) is available in Japan and is expected to have a hemostatic effect equal to or greater than that of recombinant FVIIa and activated prothrombin complex concentrates[10,11].

Recently, since the emergence of emicizumab, the importance of preventing recurrent bleeding has recently been emphasized[12]. Emicizumab is a bispecific monoclonal antibody that serves as a substitute for activated factor VIII[13]. Following its use in patients with congenital hemophilia A, emicizumab has also been shown to have a sustained anti-bleeding effect on patients with AHA[14,15]. Additionally, a groundbreaking report revealed that this therapy provides better bleeding control than conventional immunosuppressive therapy, reduces fatal infections, and improves overall survival[16]. Emicizumab has been approved by the Japanese regulatory authorities for AHA[12,17]. Owing to its extremely high cost (over 5 million Japanese Yen in this patient), its use in Japan is permitted only by hematologists who meet various institutional and physician requirements, and in other countries, emicizumab is available only off-label in hospitalized settings[18]. Although the use of emicizumab in our patient yielded promising results, further studies with a larger number of cases are needed to establish its role in the management of gastrointestinal bleeding in AHA patients. Additionally, clinicians should consider the cost-effectiveness and accessibility of this treatment.

This case highlights the importance of early detection of AHA in patients with unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding and the need for timely multidisciplinary interventions, such as endoscopic hemostasis and modern hemostatic agents, to effectively manage bleeding episodes. Multidisciplinary collaboration between endoscopists and hematologists is essential to optimize patient outcomes.

The authors would like to thank Sumiyoshi Naito and Mika Yoshida (Department of Clinical Laboratory, Health Sciences University of Hokkaido Hospital) for the technical support provided in the laboratory aspects of this study.

| 1. | Collins PW, Hirsch S, Baglin TP, Dolan G, Hanley J, Makris M, Keeling DM, Liesner R, Brown SA, Hay CR; UK Haemophilia Centre Doctors' Organisation. Acquired hemophilia A in the United Kingdom: a 2-year national surveillance study by the United Kingdom Haemophilia Centre Doctors' Organisation. Blood. 2007;109:1870-1877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 453] [Cited by in RCA: 520] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Franchini M, Veneri D. Acquired coagulation inhibitor-associated bleeding disorders: an update. Hematology. 2005;10:443-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Baudo F, Collins P, Huth-Kühne A, Lévesque H, Marco P, Nemes L, Pellegrini F, Tengborn L, Knoebl P; EACH2 registry contributors. Management of bleeding in acquired hemophilia A: results from the European Acquired Haemophilia (EACH2) Registry. Blood. 2012;120:39-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Huang YW, Saidi P, Philipp C. Acquired factor VIII inhibitors in non-haemophilic patients: clinical experience of 15 cases. Haemophilia. 2004;10:713-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tanaka I, Amano K, Taki M, Oka T, Sakai M, Shirahata A, Takata N, Takamatsu J, Taketani H, Hanabusa H, Higasa S, Fukutake K, Fujii T, Matsushita T, Mimaya J, Yoshioka A, Shima M. A 3-year consecutive survey on current status of acquired inhibitors against coagulation factors in Japan. Jpn J Thromb Hemost. 2008;19:140-153. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Roy AM, Siddiqui A, Venkata A. Undiagnosed Acquired Hemophilia A: Presenting as Recurrent Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Cureus. 2020;12:e10188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Oldenburg J, Zeitler H, Pavlova A. Genetic markers in acquired haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2010;16 Suppl 3:41-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nicolescu CM, Neşiu A, Uzum A, Laza DC, Nicolescu LC, Freiman P, Ardelean A, Ene R, Marţi TD. Esophageal ulcer associated with mild hemophilia A: case report. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2022;63:581-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Abe H, Saito M, Uno K, Koike T, Ichikawa S, Saito M, Kanno T, Hatta W, Asano N, Masamune A. A case of refractory bleeding from duodenal angioectasia with acquired hemophilia A. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2023;16:355-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ochi S, Takeyama M, Shima M, Nogami K. Plasma-derived factors VIIa and X mixtures (Byclot(®)) significantly improve impairment of coagulant potential ex vivo in plasmas from acquired hemophilia A patients. Int J Hematol. 2020;111:779-785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Takeyama M, Furukawa S, Ogiwara K, Tamura S, Ohno H, Higasa S, Shimonishi N, Nakajima Y, Onishi T, Nogami K. Coagulation potentials of plasma-derived factors VIIa and X mixture (Byclot(®) ) evaluated by global coagulation assay in patients with acquired haemophilia A. Haemophilia. 2024;30:249-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Knoebl P, Thaler J, Jilma P, Quehenberger P, Gleixner K, Sperr WR. Emicizumab for the treatment of acquired hemophilia A. Blood. 2021;137:410-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sampei Z, Igawa T, Soeda T, Okuyama-Nishida Y, Moriyama C, Wakabayashi T, Tanaka E, Muto A, Kojima T, Kitazawa T, Yoshihashi K, Harada A, Funaki M, Haraya K, Tachibana T, Suzuki S, Esaki K, Nabuchi Y, Hattori K. Identification and multidimensional optimization of an asymmetric bispecific IgG antibody mimicking the function of factor VIII cofactor activity. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shima M, Amano K, Ogawa Y, Yoneyama K, Ozaki R, Kobayashi R, Sakaida E, Saito M, Okamura T, Ito T, Hattori N, Higasa S, Suzuki N, Seki Y, Nogami K. A prospective, multicenter, open-label phase III study of emicizumab prophylaxis in patients with acquired hemophilia A. J Thromb Haemost. 2023;21:534-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shima M, Suzuki N, Nishikii H, Amano K, Ogawa Y, Kobayashi R, Ozaki R, Yoneyama K, Mizuno N, Sakaida E, Saito M, Okamura T, Ito T, Hattori N, Higasa S, Seki Y, Nogami K. Final Analysis Results from the AGEHA Study: Emicizumab Prophylaxis for Acquired Hemophilia A with or without Immunosuppressive Therapy. Thromb Haemost. 2025;125:449-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hart C, Klamroth R, Sachs UJ, Greil R, Knoebl P, Oldenburg J, Miesbach W, Pfrepper C, Trautmann-Grill K, Pekrul I, Holstein K, Eichler H, Weigt C, Schipp D, Werwitzke S, Tiede A. Emicizumab versus immunosuppressive therapy for the management of acquired hemophilia A. J Thromb Haemost. 2024;22:2692-2701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ogawa Y, Amano K, Matsuo-Tezuka Y, Okada N, Murakami Y, Nakamura T, Yamaguchi-Suita H, Nogami K. ORIHIME study: real-world treatment patterns and clinical outcomes of 338 patients with acquired hemophilia A from a Japanese administrative database. Int J Hematol. 2023;117:44-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ellsworth P, Chen SL, Jones LA, Ma AD, Key NS. Acquired hemophilia A: a narrative review and management approach in the emicizumab era. J Thromb Haemost. 2025;23:824-835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/