Published online Dec 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i12.114581

Revised: October 11, 2025

Accepted: November 11, 2025

Published online: December 16, 2025

Processing time: 84 Days and 3.6 Hours

Among patients referred for colonoscopy to evaluate bowel bleeding, many present with hemorrhoidal disease-associated bleeding and prolapse.

To compare endoscopic band ligation (EBL) with rigid proctoscope band ligation (RPBL) in patients referred for colonoscopy due to internal hemorrhoids.

This retrospective cohort study included 171 patients with previous anal bleeding and hemorrhoidal prolapse complaints who underwent routine colonoscopy who were referred for band ligation treatment. Seventy-five patients underwent EBL, and 96 underwent RPBL. Control of bleeding, prolapse recurrence, pain, tene

EBL achieved hemorrhoid symptom control in 92% of patients after a single session, compared with 63.5% for RPBL, which typically required three to four sessions (P < 0.01). Short-term prolapse was significantly lower with EBL (13.3%) than with RPBL (55.2%, P < 0.01), and long-term prolapse recurrence remained lower (8% vs 36.5%, P < 0.01). Short-term bleeding was also reduced with EBL (4% vs 19%, P < 0.01), while long-term bleeding control was comparable between groups (97.3% vs 92.7%). RPBL patients were more likely to report pain (relative risk = 1.29; 95% confidence interval: 1.08-1.54; P < 0.01). Overall satisfaction was markedly higher in the EBL group (86.7% “very satisfied”) than in the RPBL group (24%, P < 0.01).

EBL demonstrated superior control of hemorrhoidal symptoms, lower prolapse recurrence, and better short-term bleeding outcomes compared with RPBL. Long-term bleeding control and tenesmus rates were comparable; however, numerical trends favored EBL. Despite a higher per-session cost, the reduced number of sessions made overall expenses similar. EBL appears to be a more effective, efficient, and well-tolerated minimally invasive option for treating symptomatic internal hemorrhoids.

Core Tip: A practical implication of anal examination during colonoscopy is the possibility of immediate treatment of bleeding or prolapse through elastic band ligation. This procedure can be performed via rigid proctoscope band ligation (RPBL) or endoscopic band ligation (EBL). In this study, EBL controlled symptoms in a single application in 92% of patients, whereas RPBL controlled symptoms in 63.54% of patients over 3 sessions or 4 sessions (P < 0.01). EBL was superior to RPBL in terms of internal hemorrhoid symptom control, prolapse recurrence, and short-term bleeding control. Long-term bleeding control and tenesmus rates were comparable, although numerical trends favored EBL. Both methods were similar in terms of costs.

- Citation: Gomes A, Barrio E, Gomes G, Souza JHCG, Pinto PCC, Borghesi RA. Hemorrhoidal elastic band ligation during routine colonoscopy: A comparative study between flexible video endoscopy and rigid proctoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(12): 114581

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i12/114581.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i12.114581

Hemorrhoidal disease is a common condition in the adult population that is primarily characterized by bleeding, prolapse, discomfort or anal pain, and itching. Hemorrhoids are the most prevalent anorectal pathology in the Western world and are a very common impetus for chronic bleeding consultations. In patients with first-degree or third-degree hemorrhoids, conservative treatment and nonsurgical procedures are recommended. Patients with bleeding are referred for colonoscopy to identify the origin of the bleeding and for colorectal cancer screening[1,2]. Thus, an appropriate examination of the anal canal is mandatory in the evaluation of patients with a history of intestinal bleeding[3].

Hemorrhoids are classified according to their internal (above the dentate line and covered by the anal mucosa) and external (below the dentate line and covered by anoderm) locations. Internal hemorrhoids are classified by the degree of prolapse. Practical interest in the classification of hemorrhoids is based on the individualization of treatment that will benefit the patient the most. It can be a conservative, instrumental, or surgical treatment. Among the instrumental treatments offered, band ligation is the most widely used as it has the lowest symptom recurrence rates and need for retreatment[4]. It is safe and relatively painless. It is performed on an outpatient basis and consists of placing rubber bands above the dentate line strangling the hemorrhoid, leaving a small amount of fibrotic tissue where the scar fixes the mucosa to the submucosa and no new hemorrhoidal piles develop[5].

Band ligation was first introduced in the United States in 1951 and has been one of the pillars of hemorrhoids treatment. Band ligation is the first option for grade I, grade II, or grade III hemorrhoids that prolapse or bleed[6]. It is the most commonly used and the most cost-effective technique. The healing rate is 86.6% with one session, and the recurrence rate is 11% in 2 years. Only 7.5% of patients require new treatment, whether through ligation or surgery[4,7]. The recurrence rate was 3.7% at 1 year (22 patients), 6.6% at 2 years, and 13.0% at 5 years[8]. Internal hemorrhoid ligation with an average of three elastic bands placed in a single session showed an excellent result in 80% of patients with second-degree hemorrhoids and 54% of patients with third-degree hemorrhoids[9]. Although the efficacy of band ligation is lower than that of surgery for the treatment of grade III prolapsed hemorrhoids, band ligation is recommended as a first-line treatment for these lesions because of its safety, simplicity and ability to be performed as an outpatient procedure[10].

Conventional band ligation is performed using a rigid proctoscope, which is difficult to maneuver, has a narrow field of vision and lacks photographic documentation. Rigid proctoscope band ligation (RPBL) allows the placement of three rubber bands on average, and each application requires the placement and removal of the proctoscope, which can cause rubber displacement with subsequent bleeding. Su et al[11] showed no difference in ligature diameters when using 9-mm or 13-mm endoscopic devices[11].

Endoscopic band ligation (EBL) allows for a greater number of elastic band placements in a single endoscope insertion, facilitating more precise visualization of the ligature site and photographic documentation of the procedure (Video 1). The placement of multiple bands above the hemorrhoids also contributes to scar retraction, thereby improving prolapse[12,13].

Both techniques are easy to perform, well tolerated, have a good and rapid therapeutic effect, and have comparable results[14,15]. However, hemorrhoid ligation is not without complications. Patients taking aspirin, anti-inflammatory drugs, or anticoagulants may experience bleeding. Mild-to-moderate, but not significant, pain occurs in approximately 25% of patients. Infectious complications have been described, mainly in immunocompromised patients[7]. The largest study on endoscopic hemorrhoid band ligation available was published by Su et al[8] and included 759 patients. A 95% satisfaction rate was observed with a follow-up of 55 months. The main complication was rectal bleeding, which was controlled in 98% of patients after a single band ligation session. The recurrence rates at 1, 2, and 5 years were 3.7%, 6.6%, and 13%, respectively.

Davis et al[16] reported 500 cases of combined colonoscopy and three-quadrant hemorrhoidal ligation, concluding that it is a safe and effective method in the treatment of symptomatic internal hemorrhoids. Additionally, while performing hemorrhoidal ligation in the same setting as that for colonoscopy, the patient undergoes a mechanical bowel preparation and is under moderate sedation, which makes this procedure easier for the surgeon to perform and more comfortable for the patient compared with office ligation without sedation. Wehrmann et al[14] published a randomized prospective study with 100 patients with recurring bleeding episodes and undergoing colonoscopy and compared EBL and RPBL, with an average follow-up of 12 months, and concluded that both methods are highly comparable. However, when EBL is performed, significantly fewer treatment sessions are required. Cazemier et al[15] reported a study with 41 patients comparing a rigid proctoscope (19 patients) and flexible endoscope (22 patients) for elastic band ligation of internal hemorrhoids and concluded that both techniques are easy to perform, well tolerated and have a good and fast effect. It is easier to perform more ligations with the flexible endoscope. Additional advantages of the flexible scope are maneuverability and photographic documentation. However, treatment with the flexible endoscope might be more painful and more expensive.

Using front view and colonoscope rectal retroflexion, Fukuda et al[17] described a classification to predict the risk of bleeding and the need for endoscopic treatment of internal hemorrhoids with band ligation. They used three aspects: (1) Range: Extension of the circumferential distribution of internal hemorrhoids to five degrees (0 - without hemorrhoids; 1 - a quarter of the circumference; 2 - half of the circumference; 3 - three quarters of the circumference; 4 - the entire circumference); (2) Form: Wide hemorrhoid diameter (0 - without hemorrhoid; 1 - less than 12 mm; 2 - greater than 12 mm); and (3) Red color signs: Presence of color change on the surface of hemorrhoidal piles according to the rules of esophageal varices, including telangiectasia, stripe marks and hematocystic points.

This retrospective cohort study included 171 patients who underwent routine colonoscopy and video anoscopy with previous complaints of anal bleeding and hemorrhoidal prolapse and were referred for band ligation treatment.

In the early years of the study period, the RPBL technique was the only method available at our institution. The EBL technique was introduced later and gradually adopted. Over time, based on accumulated clinical experience, the EBL method demonstrated faster and more effective treatment responses. Consequently, EBL became the preferred approach whenever materials were available and authorized by health insurance providers. Thus, patient allocation to the EBL or RPBL groups was not randomized but determined by temporal, logistical, and institutional factors.

This study was conducted at Endoclinic Endoscopy Center in Sorocaba, Brazil. From October 2006 to May 2025, all procedures were performed by one endoscopist and coloproctologist (Gomes A) with extensive experience in this field.

All patients underwent colon preparation. Standardized colon preparation was performed after patients had abstained from a fiber diet 2 days before the examination and had been administered with 10 mg of bisacodyl the night before and 750 mL of 10% mannitol 4 hours before the examination. If the patient uses medications such as ticlopidine or clopidogrel, he was instructed to stop taking them 7 days earlier or use rivaroxaban, dabigatran, or apixaban 3 days earlier, with the approval of the clinical doctor. The patient was also instructed to not use aspirin or any anticoagulant 7 days before band ligation and for another 2 weeks after band ligation.

All examinations were performed with the patients in a supine or left lateral position, with noninvasive monitoring of the heart rate and pulse oximetry throughout the procedure and the use of supplementary oxygen if necessary. Intravenous medication was administered for midazolam sedation (0.05 mg/kg - 0.1 mg/kg), fentanyl (0.5-1 μg/kg - 1 μg/kg), and propofol (10 mg titration doses for sedation maintenance as needed). A video colonoscope and video endoscope manufactured by OlympusTM, PentaxTM, or FujinonTM, and a transparent and disposable plastic proctoscope (Plastic WayTM or KolplastTM) were used.

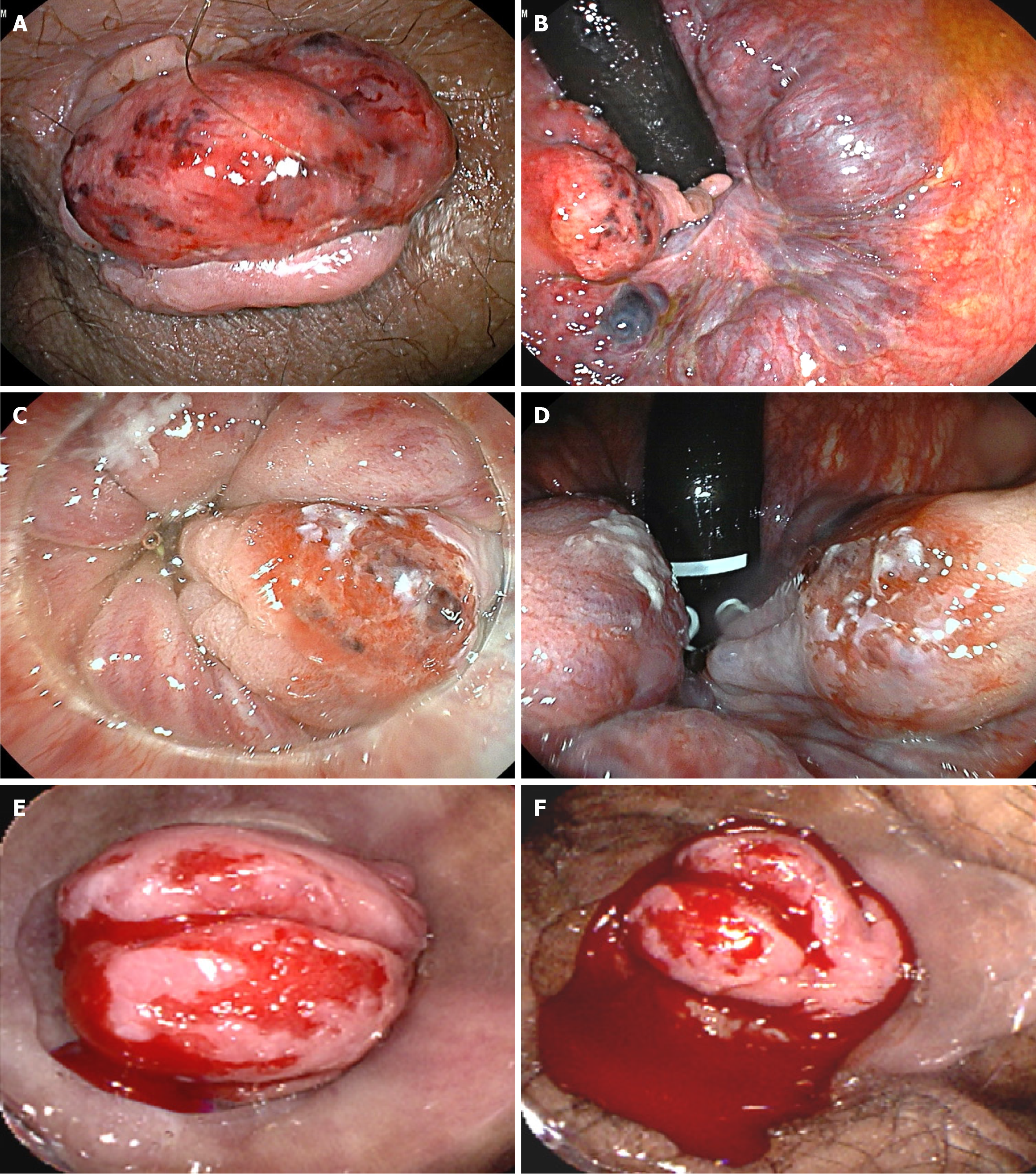

The patients underwent digital anal rectal examination, after which the colonoscope was introduced into the rectum via liquid content aspiration. A careful evaluation with a front view of the rectum, dentate line, and anal canal was performed. An anoscope was used to evaluate the anal canal and perianal region. The results were then annotated. The polyps, internal hemorrhoidal plexus, dentate line, anal canal, and perianal region are visualized with identification and photographic documentation in these procedures. After this evaluation, the colonoscopy exam was performed. After the end of colonoscopy, patients with an indication for hemorrhoid treatment underwent EBL or RPBL. Patients who experienced bleeding and/or hemorrhoidal prolapse were included in the comparative study. Figure 1 shows 3 cases of evident bleeding in internal hemorrhoids that were found during colonoscopies and treated with band ligation.

Inclusion criteria: Patients with history of anal bleeding and hemorrhoidal prolapse classified as degrees I, II, and III of Dennison were included.

Exclusion criteria: Patients with very advanced hemorrhoidal disease (i.e., cases of internal grade IV hemorrhoids and bulky external hemorrhoids with exuberant skin tags) were excluded.

Contraindications to band ligation treatment: (1) Colorectal cancer or suspicious polyps during colonoscopy; (2) Anal fissure, internal sphincter hypertonia, perianal dermatitis, anorectal fistula, and anorectal abscess; (3) Sexually transmitted diseases: Anal human papillomavirus, herpes, syphilis, human immunodeficiency virus; (4) Crohn’s disease and immunosuppression do not contraindicate the procedure, but the application limits the treatment to only one pile. Band ligation is preferable to surgery in patients with poor general condition and impaired healing; and (5) Patients with known latex hypersensitivity.

Follow-up losses: Of the 186 patients identified in the system, 15 could not be contacted and were excluded, leaving 171 for analysis. Hemorrhoidal disease was described using two classifications. The first classification of internal hemorrhoids was used according to Dennison for categorization of internal hemorrhoids as grade I, grade II, grade III or grade IV based on prolapse and bleeding (Table 1)[18]. The second classification system was based on the endoscopic classification of Fukuda et al[17]. This system is used to evaluate the degree of internal occupation of piles and cases that presented evidence of active or stigmata of bleeding (Table 2). Some studies have shown similarity between the bleeding stigmas of esophageal varices - classified according to the Beppu classification, which includes the size and morphology of varicose veins, cherry red spots - and other aspects of hemorrhoids, including red wale markings and hematocysticspots[19]. The size of the hemorrhoids and the presence of red spots are closely related to previous bleeding. Visualization of these aspects and the location of bleeding is facilitated by video anoscopy and was used in this study to indicate the optimal locations for rubber band placement. The choice of procedure to be performed was based on the availability of the material at the time of execution, approval by the patient's health insurance, and the cost.

| Classification | |

| Grade I | Bleeding during evacuation, without prolapse |

| Grade II | Prolapse during evacuation with spontaneous return, with or without bleeding |

| Grade III | Spontaneous prolapse or during evacuation, with manual reduction, with or without bleeding |

| Grade IV | Externalized and irreducible, and ischemia, thrombosis or gangrene may occur, with or without bleeding |

| Classification | |

| Grade I | Occupies a quarter of the anal circumference |

| Grade II | Occupies half of the anal circumference |

| Grade III | Occupies three quarters of the anal circumference |

| Grade IV | Occupies the entire circumference of the anal circumference |

EBL was performed using the following devices: 6 Shooter® Universal Saeed®, Multi-Band Ligator (Cook Medical, IN, United States), Speedband Superview Super 7TM, Multiple Band Ligators (Boston Scientific Corporation, MA, United States), and Endoscopic Multi-Band Ligator Set, 6 Bands (Micro-Tech, MI, United States). A cylinder with 6-7 elastic bands was adapted to the gastroscope. The elastic bands were released after the hemorrhoids had been aspirated into the cylinder. The band ligation begins with the first elastic placed on the largest pile or the pile that presents the place of probable prior bleeding, 2 mm above the dentate line, until the ligation of all piles, which typically involves 5-7 bands. The assistant must push and hold the large hemorrhoidal piles of III degree into the anal canal so that the ligatures can grasp them. In the EBL, the rectal mucosa, above the piles, is aspirated and ligated to avoid the descent of the mucosa and vascular cushions. The aspirated hemorrhoid pile is strangled by the detached elastic, thereby acquiring the polypoid aspect. The seized tissue will suffer necrosis in 3-7 days, and shallow ulcers will form after the elastic bands have fallen. The time spent performing the procedure ranges from 7 minutes to 10 minutes. New applications can be performed after 40-60 days if the results are not satisfactory. It can usually eradicate hemorrhoids in approximately 90% of cases with only one session. In our clinic, the average EBL cost, including the material used and medical fees, excluding colonoscopy, is approximately 500 dollars.

The aspiration system with tweeted traction, a 9 mm drum caliber, and a 13 mm macro ligature device (Fradel-MedTM, Ferrari MedicalTM) were used. RPBL allows the placement of one elastic ligation at a time, with three ligatures on average each session. The device must be removed, and a new elastic ring must be mounted on the kit. The anoscope must be removed from each application. Hemorrhoid pile aspiration and tweezer traction are then performed. It is considered satisfactory when the ligatures are located proximally to the dentate line and the patient does not report strong pain. In our clinic, the average cost of RPBL, excluding colonoscopy, including the material used and medical fees, is approximately 200 dollars.

Mild-to-moderate pain, reported as tenesmus or anorectal discomfort, occurs in approximately 20% of patients and lasts from hours to 30 days. Severe pain associated with urinary retention or dysuria, hyperemia, and perianal edema are signs suggestive of a perianal abscess and should be treated with antibiotics and surgical drainage. Severe pain associated with external hemorrhoidal thrombosis can be treated with topical ointments and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Slight bleeding occurs a few days later without the need for specific treatment. Heavy bleeding with clinical repercussions is rare and requires hospitalization. Transient urinary retention may occur without the need for a urinary catheter, but the patient may experience small volumes of urine leakage.

After band ligation, all patients received a medical prescription of ketoprofen (100 mg) twice a day for 3 days and dipyrone (500 mg) 4 times a day if they experienced pain. All patients were examined or contacted by phone, and a questionnaire was administered months or years after the procedures. The study addressed the following questions.

What were the symptoms before band ligation: (1) Bleeding, quantity, and duration; (2) Prolapse; (3) Pain (scale of pain applied); and (4) Other symptoms.

Did you experience complications immediately after BL: (1) Presence, quantity, and duration of bleeding; (2) Prolapse; (3) Pain (applied to a pain scale); (4) Tenesmus (the feeling of needing to evacuate the bowel even when it is empty); (5) Urinary retention; (6) Fever; and (7) others.

How did the symptoms look after the band ligation: (1) Bleeding; (2) Prolapse; (3) Pain (scale of pain applied); (4) Others; (5) It has not changed anything; (6) Worsened; (7) It has improved little; and (8) It has improved a lot.

Likert scale of 4 points of satisfaction with the procedure: (1) Very dissatisfied; (2) Dissatisfied; (3) Satisfied; and (4) Very satisfied. Regarding pain, the Numerical Verbal Pain Scale (1-10) was used.

The following criteria were used for bleeding: B0 - without bleeding; B1 - light, sporadic bleeding, only when cleaning; B2 - moderate bleeding, mixed with feces; B3 - intense bleeding, drips in the toilet; B4 - anemia. Treatment was considered complete in asymptomatic patients when rectal retroflexion revealed no hemorrhoids greater than grade II. Failure was demonstrated by the recurrence of bleeding, presence of red spots on hemorrhoids of any endoscopic degree, and presence of endoscopic stage II or larger hemorrhoids. The average follow-up period was 41.27 months and 50.15 months for the EBL group and 50.15 months for the RPBL group.

A potential limitation of this study is the non-random allocation of patients to treatment groups. The choice of technique was influenced by the period during which the procedure was performed, the availability of materials, and authorization by health insurance providers. These external factors may have contributed to baseline demographic differences and introduced selection bias, which is inherent to the retrospective design. To minimize bias, medical academics admin

Data were described by absolute frequencies and percentages (qualitative variables) and by measures of central tendency and dispersion [mean ± SD; median (minimum-maximum)] for quantitative variables. The baseline characteristics of the ligation types were compared using Fisher’s exact test for qualitative variables and the Mann-Whitney U test for quantitative variables.

The log-binomial regression model was used to compare ligation types regarding binary outcomes - pain (reclassified according to different cutoff points), tenesmus, prolapse, bleeding, prolapse recurrence, and bleeding recurrence[20]. This allows for the direct estimation of relative risks (RRs). The model was adjusted for potential confounding variables that, in a previous analysis, showed differences in sex, presence of previous prolapse, endoscopic classification of the hemorrhoid, and total number of ligations between the groups. All graphs were created using RStudio software, version 2024.12.1, and Statistical Analysis System version 9.4 was used for the analyses. A significance level of 5% was adopted for all analysis.

All the characteristics of the patients before elastic ligation are presented in Table 3. The mean age was 53.56 years (27-83 years) for EBL and 50.71 years for RPBL (23-84 years). The EBL group included 7 (9.33%) women and 68 (90.67%) men, and the RPBL group included 31 women (32.29%) and 65 men (67.71%), P < 0.01. In the EBL group, all 75 patients had prolapse and bleeding prior to treatment (100%). In the RPBL group, 92.71% had prior prolapse and 97.92% had some degree of bleeding before ligation.

| Variable | EBL (n = 75) | RPBL (n = 96) | P value1 |

| Age | 53.56 ± 13.1 | 50.71 ± 13.07 | 0.19 |

| 56 (27-83) | 51 (23-84) | ||

| Sex | < 0.01 | ||

| Female | 7 (9.33) | 31 (32.29) | |

| Male | 68 (90.67) | 65 (67.71) | |

| Previous prolapse | 0.02 | ||

| No | 0 (0) | 7 (7.29) | |

| Yes | 75 (100) | 89 (92.71) | |

| Previous bleeding | 0.50 | ||

| No | 0 (0) | 2 (2.08) | |

| Yes | 75 (100) | 94 (97.92) | |

| Bleeding classification | 0.17 | ||

| B0 | 3 (4) | 2 (2.08) | |

| B1 | 20 (26.67) | 28 (29.17) | |

| B2 | 22 (29.33) | 35 (36.46) | |

| B3 | 26 (34.67) | 31 (32.29) | |

| B4 | 4 (5.33) | 0 (0) | |

| Dennison hemorrhoid grade | 0.33 | ||

| I | 1 (1.33) | 6 (6.25) | |

| II | 52 (69.33) | 63 (65.63) | |

| III | 22 (29.33) | 27 (28.13) | |

| Endoscopic classification of hemorrhoids | 0.02 | ||

| II | 13 (17.33) | 33 (34.38) | |

| III | 62 (82.67) | 62 (64.58) | |

| IV | 0 (0) | 1 (1.04) | |

| Number of bands per session | 6.2 ± 0.96 | 3.21 ± 0.48 | < 0.01 |

| 6 (3-7) | 3 (2-5) | ||

| Number of sessions | 1.09 ± 0.29 | 1.76 ± 0.72 | < 0.01 |

| 1 (1-2) | 2 (1-4) | ||

| Total bands | 6.79 ± 2.13 | 5.58 ± 2.25 | < 0.01 |

| 6 (3-14) | 6 (2-12) | ||

| Follow-up time (months) | 41.27 ± 30.02 | 59.15 ± 62.29 | 0.64 |

| 39.14 (0.1-138.52) | 38.08 (1.18-225.23) |

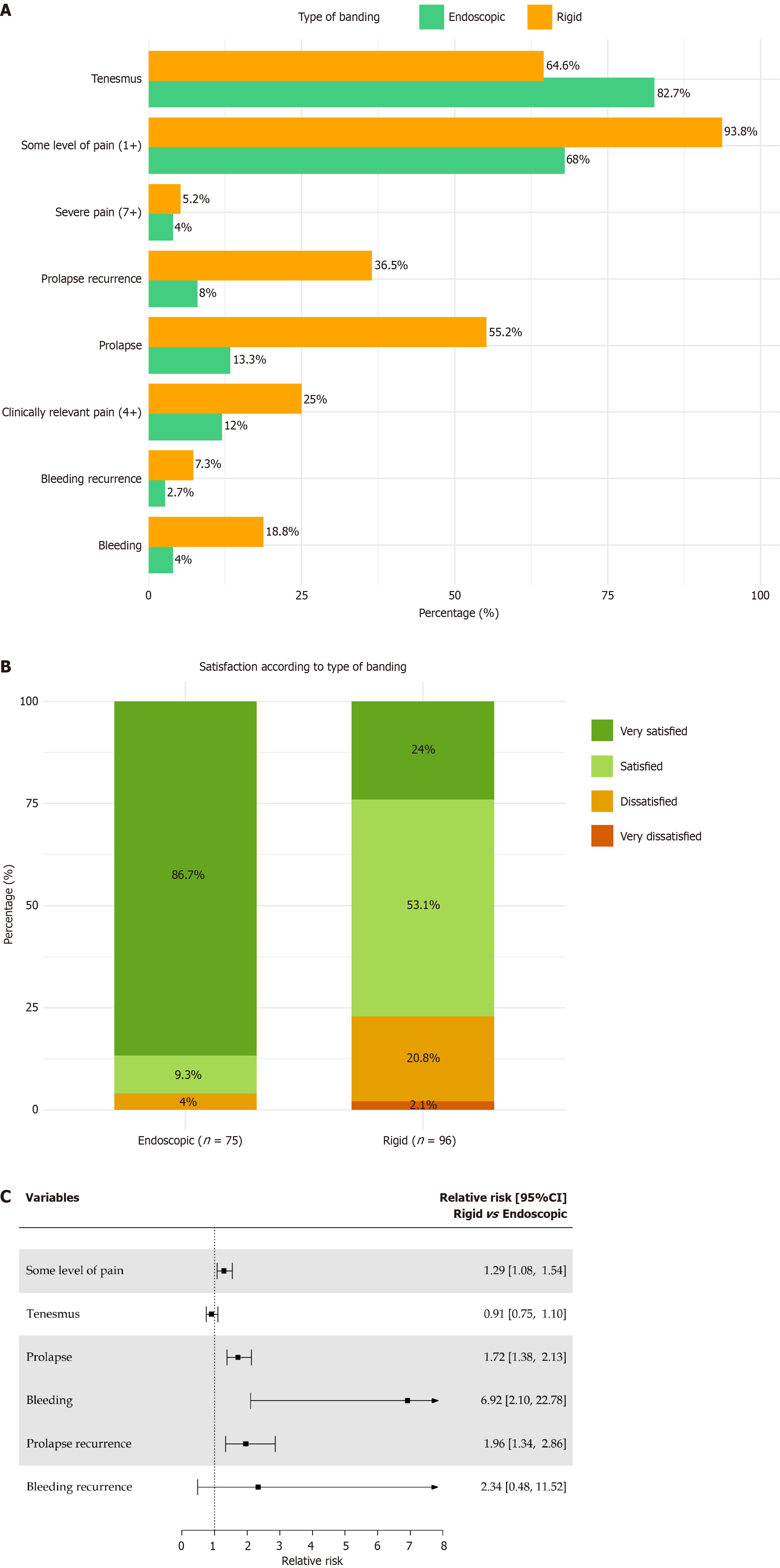

The results after band ligation are presented in Table 4. The distribution of symptoms according to ligation type is presented in Figure 2A. A forest plot of the RRs of clinical outcomes according to ligation type is presented in Figure 2B. A total of 171 band ligations, including 96 RPBL (56.14%) and 75 EBL (43.86%), were performed. The average number of rubber bands applied per session was 6.2 and 3.21 in the EBL group and 3.21 in the RPBL group (P < 0.01). The number of sessions was 82 in the EBL group and 169 in the RPBL group, resulting in an equivalent number of rubber bands applied in both groups (EBL 509 vs RPBL 536).

| Variable | EBL (n = 75) | RPBL (n = 96) | P value1 |

| Age | 53.56 ± 13.1 | 50.71 ± 13.07 | 0.19 |

| 56 (27-83) | 51 (23-84) | ||

| Sex | < 0.01 | ||

| Female | 7 (9.33) | 31 (32.29) | |

| Male | 68 (90.67) | 65 (67.71) | |

| Previous prolapse | 0.02 | ||

| No | 0 (0) | 7 (7.29) | |

| Yes | 75 (100) | 89 (92.71) | |

| Previous bleeding | 0.50 | ||

| No | 0 (0) | 2 (2.08) | |

| Yes | 75 (100) | 94 (97.92) | |

| Bleeding classification | 0.17 | ||

| B0 | 3 (4) | 2 (2.08) | |

| B1 | 20 (26.67) | 28 (29.17) | |

| B2 | 22 (29.33) | 35 (36.46) | |

| B3 | 26 (34.67) | 31 (32.29) | |

| B4 | 4 (5.33) | 0 (0) | |

| Dennison hemorrhoid grade | 0.33 | ||

| I | 1 (1.33) | 6 (6.25) | |

| II | 52 (69.33) | 63 (65.63) | |

| III | 22 (29.33) | 27 (28.13) | |

| Endoscopic classification of hemorrhoids | 0.02 | ||

| II | 13 (17.33) | 33 (34.38) | |

| III | 62 (82.67) | 62 (64.58) | |

| IV | 0 (0) | 1 (1.04) | |

| Number of bands per session | 6.2 ± 0.96 | 3.21 ± 0.48 | < 0.01 |

| 6 (3-7) | 3 (2-5) | ||

| Number of sessions | 1.09 ± 0.29 | 1.76 ± 0.72 | < 0.01 |

| 1 (1-2) | 2 (1-4) | ||

| Total bands | 6.79 ± 2.13 | 5.58 ± 2.25 | < 0.01 |

| 6 (3-14) | 6 (2-12) | ||

| Follow-up time (months) | 41.27 ± 30.02 | 59.15 ± 62.29 | 0.64 |

| 39.14 (0.1-138.52) | 38.08 (1.18-225.23) |

Patients undergoing rigid ligation (93.75%) have a 29% higher risk of reporting some level of pain than those undergoing endoscopic ligation (68%), P < 0.01 [RR = 1.29; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.08-1.54]. No difference was observed in the incidence of clinically relevant pain between the ligation types (12% EBL vs 25% RPBL, P = 0.10). No difference was observed in the incidence of severe pain between the ligation types (EBL 4%; RPBL 5.21%; P = 0.75). No evidence of a difference in the incidence of tenesmus was noted between the ligation types (EBL 82.67% vs RPBL 64.58%; P = 0.35).

On average, the short-term risk of prolapse (6 months) was 72% higher in patients undergoing rigid ligation than in those undergoing endoscopic ligation (EBL 13.33% vs RPBL 55.21%, P < 0.01). Patients undergoing rigid ligation have a 96% higher risk of prolapse recurrence in the long term than those undergoing endoscopic ligation (EBL 8% vs RPBL 36.46% P < 0.01).

It was estimated that, on average, among patients undergoing rigid ligation, the risk of bleeding in the short term (6 months) was almost 7 × higher compared to patients undergoing endoscopic ligation (EBL 4% vs RPBL 18.75%, P < 0.01). No evidence of a difference in long-term rebleeding was observed between the types of ligations regarding (EBL 2.67% vs RPBL 7.29%, P = 0.29). The post-band ligation follow-up time was 60 months for the RPBL group and 41 months for the EBL group. Among the EBL group, 86.7% reported being “very satisfied” with the procedure, whereas 24% of patients in the RPBL group reported the same. No patients in the EBL group reported being “very dissatisfied”, and 2.1% of patients in the RPBL group reported this perception (P < 0.01; Figure 2C).

During colonoscopy, hemorrhoidal bleeding or prolapse can be effectively managed through band ligation. RPBL is performed using a rigid proctoscope, whereas EBL employs a variceal ligation kit adapted to the gastroscope. The present study compared the clinical efficacy, patient satisfaction, and procedural outcomes of these two techniques in a real-world setting.

In this study, EBL provided hemorrhoid symptom control in a single application in 92% of patients, whereas RPBL achieved hemorrhoid symptom control in 63.54% of patients requiring 3 or 4 sessions (P < 0.01). The average number of sessions was 82 in the EBL group and 169 in the RPBL group, resulting in an equivalent number of rubber bands applied in both groups (EBL 509 vs RPBL 536). In all, 169 RPBL sessions were performed in 96 patients (1.7 sessions), and 82 EBL sessions were performed in 75 patients, which resulted in an average of 1.09 sessions per patient. The average numbers of sessions performed during EBL and RPBL per patient were 1.09 (0.29) and 1.76 (0.72), respectively, with medians of 1 (1-2) for EBL and 2 (1-4) for RPBL.

Excluding the cost of colonoscopy, the cost of an RPBL session in our clinic is approximately 200 dollars, while the cost of EBL is 500 dollars, including materials and medical fees. This indicates that the final costs are equivalent in some cases. The amounts spent can be extrapolated for each situation and depend on the location, considering that at least twice as many RPBL sessions will be necessary. RPBL had the lowest initial cost; however, the costs are equivalent in the long term because more applications of RPBL are needed. The cost analysis in the present study was limited to direct pro

Therefore, although the number of sessions required for treatment was comparable between groups, leading to similar cumulative procedural costs, a formal cost-effectiveness analysis would be required to comprehensively evaluate the long-term economic impact of each technique. However, indirect costs, such as repeated visits, work absence, and management of potential complications, were not assessed and should be addressed in future studies.

Compared with traditional hemorrhoidectomy, EBL is associated with lower complication rates, shorter recovery times, less time off work, and less intense pain, and hospitalization is not required. Traditional surgery has the advantage of better short-term and long-term results and lower recurrence rates but at the expense of higher rates of immediate and late-term complications.

In the short term, patients who underwent RPBL had a 55.21% prolapse rate, while those who underwent EBL had a 13.33% prolapse rate (P < 0.01), and therefore, the risk of prolapse was 72% greater in the rigid ligation group. Long-term prolapse recurrence was significantly greater in the RPBL group (36.46%) than in the EBL group (only 8%; P < 0.01). Compared with patients who underwent endoscopic ligation, patients who underwent rigid ligation had a 96% greater risk of prolapse recurrence.

With respect to bleeding control, EBL was more efficient in the short term, with a bleeding rate of 4%, whereas that RPBL was 18.96% (P < 0.01). In the short term, patients who underwent RPBL had a nearly 7 × greater risk of bleeding than did those who underwent EBL. After the sessions were completed, long-term bleeding control was similar in the two groups: 97.33% in the EBL group and 92.71% in the RPBL group (P = 0.29). Patients who underwent rigid ligation had a 29% greater risk of reporting some level of pain than did those who underwent endoscopic ligation (RR = 1.29; 95%CI: 1.08-1.54).

EBL achieved superior short-term control of hemorrhoidal symptoms, with 92% of patients responding after a single session, whereas RPBL required an average of three to four sessions to achieve similar control (P < 0.01). The EBL group also demonstrated lower recurrence of prolapse (8% vs 36.5%) and a markedly lower short-term bleeding rate (4% vs 19%), consistent with the hypothesis that direct visualization under endoscopy allows for more precise and uniform band placement above the dentate line. This positioning likely minimizes mucosal trauma and incomplete ligation - me

No difference in the incidence of clinically relevant pain between the types of ligations was observed (EBL 12% vs RPBL 25%, P = 0.10); moreover, no difference was found in intense pain (EBL 4% and RPBL 5.91%, P = 0.75). No evidence of a difference in the incidence of tenesmus between the types of ligations was observed, with rates of 82.67% and 64.58% in the EBL and RPBL groups, respectively (P = 0.35).

Although the rates of tenesmus and long-term bleeding control did not differ significantly between groups, the numerical trends observed may have clinical implications. The lower incidence of tenesmus in the EBL group (82.7% vs 64.6%) and the higher long-term bleeding rate than in the RPBL group (7.3% vs 2.7%) suggest potential advantages of EBL that might not have reached statistical significance due to the limited sample size. These findings highlight the importance of interpreting results in both statistical and clinical contexts. To confirm whether these differences are clinically meaningful, larger, prospective studies are needed.

In terms of satisfaction, evidence of a difference was observed between the types of banding. Among patients who underwent EBL, 86.7% reported being “very satisfied” with the procedure, whereas in the RPBL group, this proportion was only 24%. In addition, no cases of “very dissatisfied” were recorded in the EBL group, whereas 2.1% of patients in the RPBL group reported this perception. Fisher’s exact test revealed a significant difference between groups (P < 0.01), as the distribution of responses indicated greater satisfaction with the EBL technique. The performance of colonoscopies for the prevention of CRC or for the evaluation of intestinal bleeding, and the combination of elastic ligation of hemorrhoids using bowel preparation and deep sedation were very satisfactory according to patients, compared with traditional methods of outpatient ligation, in which sedation and bowel preparation are not performed. All contacted patients in the EBL group responded that they would undergo the procedure again if necessary.

All patients who complained of anal discomfort or discomfort and pain, which could be controlled with analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs, experienced these symptoms within the first few days after the procedure. No patient experienced early bleeding due to the ligature displacement. No patients presented with stenosis or incontinence complaints. Patients who experienced bleeding recurrence 2-11 months after the initial procedure required a second ligation session.

Band ligation of the hemorrhoids can be performed for both internal hemorrhoids and symptomatic mixed (prolapses and/or bleeding) hemorrhoids of any degree without prior treatment or as a complementary therapy in patients undergoing another type of treatment. After the end of band ligation treatment, skin tags and residual external hemorrhoids can be removed under local anesthesia if they cause symptoms such as pain, swelling with discomfort and if they hinder hygiene, causing itching.

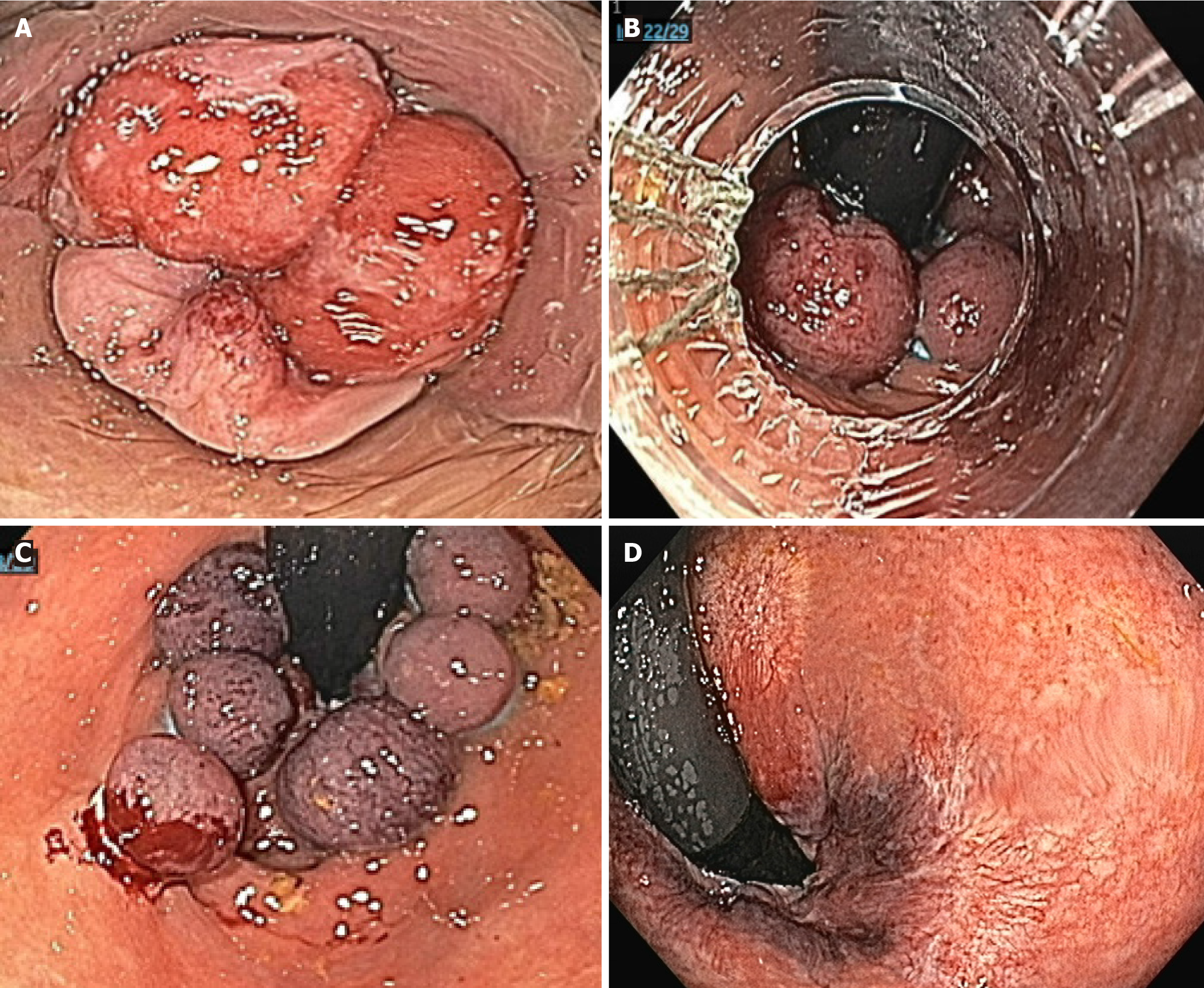

EBL allows complete hemorrhoid treatment, i.e., it can cure hemorrhoids within a single day in approximately 90% of cases. EBL is quick, can be completed in 10-15 minutes, is simple, safe, and effective, and has low complication rates. EBL performed under sedation reduces discomfort. The low complication rates, high resolution rates, and early return to work (usually within 1-2 days) justify the cost. Regression of hemorrhoid severity provided by band ligation is important (Figure 3). Even if the regression of the piles is incomplete, a partial or even complete reduction in symptoms is notable for patient satisfaction. The same dissatisfaction and complications as traditional hemorrhoidectomy are not observed, as band ligation avoids anal stenosis or gas and fecal incontinence, which are two difficult postsurgical complications.

A systematic review by Shanmugam et al[10] compared band ligation vs hemorrhoidectomy and showed that band ligation is less invasive, less painful, has a lower complication rate, and results in faster recovery. However, the long-term efficacy of surgery increases with the increasing degree of prolapse, at least for grade III and grade IV hemorrhoids. However, this was at the expense of increased pain, greater immediate complications (urinary retention, fecal impaction, hemorrhage, and surgical wound abscess) and late complications (anal stenosis, residual fissure, fecal incontinence, and residual skin tags), and longer time away from work. However, band ligation, which is performed on an outpatient basis, is less invasive and easy to perform. Band ligation can be adopted as the first-choice treatment for grade I, grade II, and grade III hemorrhoids, offering similar results but without surgery-induced side effects. Hemorrhoidectomy is indicated for patients with exuberant skin tags, predominant external hemorrhoids, advanced cases of grade III and grade IV hemorrhoids, and recurrence after band ligation[21].

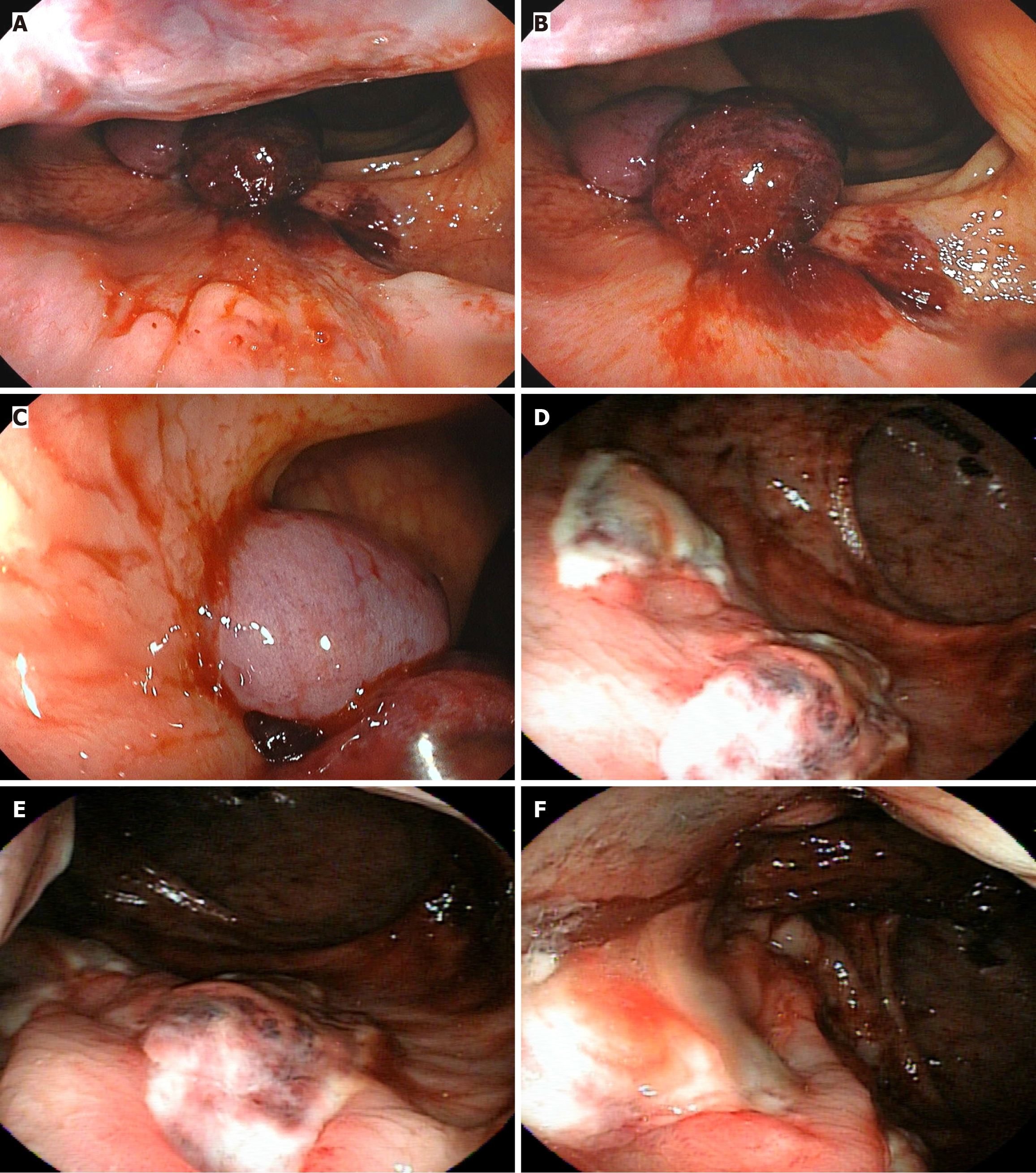

Our results are in strong agreement with those reported by Wehrmann et al[14], who conducted a prospective, randomized trial comparing flexible endoscopic ligation using a video endoscope with the conventional rigid proctoscope technique. They found that EBL was equally safe but significantly more effective, with lower recurrence rates, less post-procedural discomfort, and greater patient acceptance. Similarly, Cazemier et al[15] observed that flexible endoscopic ligation offered better visualization, easier access to higher hemorrhoidal cushions, and improved patient tolerance, supporting the transition from rigid to flexible endoscopic methods (Figure 4).

Our findings extend those observations that confirm EBL’s advantages in symptom control and patient satisfaction. The markedly lower recurrence of prolapse in our EBL group (8% vs 36.5% with RPBL, P < 0.01) parallels the reduction in recurrence reported by Wehrmann et al[14], further suggesting that improved visualization and suction-assisted band placement with flexible endoscopes contribute to more complete mucosal fixation and fibrosis.

This study has several limitations. Its retrospective design and the non-random allocation of patients to treatment groups may have introduced selection bias. The choice of technique depended on the period of the study, material availability, and health insurance approval, which may explain some of the baseline demographic differences observed. Despite these limitations, the real-world data presented here provide valuable insight into the comparative effectiveness of EBL and RPBL in routine clinical practice.

From a procedural standpoint, EBL offers several practical advantages. The use of a flexible endoscope allows for treatment during colonoscopy, enabling complete hemorrhoidal therapy under sedation and bowel preparation. This reduces patient discomfort and improves visualization, potentially accounting for the lower rates of recurrence and bleeding observed. Additionally, by enabling hemorrhoid management during diagnostic colonoscopy, EBL may enhance cost-effectiveness.

In summary, EBL appears to represent an important advancement in the minimally invasive management of symptomatic internal hemorrhoids. It offers higher efficacy, fewer required sessions, lower recurrence and bleeding rates, and greater patient satisfaction compared with RPBL. Although its per-session cost is higher, the overall procedural efficiency and patient benefits justify its use as a first-line approach for most cases of grade I-III hemorrhoids. Future prospective, multicenter studies incorporating long-term follow-up and comprehensive cost analyses are warranted to confirm these findings and further define EBL’s role in the therapeutic algorithm for hemorrhoidal disease.

EBL was superior to RPBL in controlling hemorrhoidal symptoms, reducing prolapse recurrence, and achieving better short-term bleeding control. Both techniques showed comparable outcomes in long-term bleeding control and post-procedural tenesmus; however, the numerically lower incidence of tenesmus and higher long-term non-bleeding rate in the EBL group suggest potential clinical advantages that may not have reached statistical significance due to the limited sample size. Although EBL carries a higher per-session cost, its reduced number of required applications resulted in comparable overall procedural expenses. Collectively, these findings indicate that EBL represents a more effective, efficient, and patient-preferred minimally invasive option for the treatment of symptomatic internal hemorrhoids. Future prospective studies with larger cohorts and formal cost-effectiveness analyses are warranted to confirm these observations and further define EBL’s role in routine clinical practice.

We thank Marco Aurélio M. C. Regis created tables and graphics, and figures. Estela Cristina Carneseca conducted statistical analysis and created the tables, graphics, and figures.

| 1. | Koning MV, Loffeld RJ. Rectal bleeding in patients with haemorrhoids. Coincidental findings in colon and rectum. Fam Pract. 2010;27:260-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Allen E, Nicolaidis C, Helfand M. The evaluation of rectal bleeding in adults. A cost-effectiveness analysis comparing four diagnostic strategies. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:81-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gomes A, Minata MK, Jukemura J, de Moura EGH. Video anoscopy: results of routine anal examination during colonoscopies. Endosc Int Open. 2019;7:E1549-E1562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Yeo D, Tan KY. Hemorrhoidectomy - making sense of the surgical options. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16976-16983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Fukuda A, Kajiyama T, Arakawa H, Kishimoto H, Someda H, Sakai M, Tsunekawa S, Chiba T. Retroflexed endoscopic multiple band ligation of symptomatic internal hemorrhoids. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:380-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Daram SR, Lahr C, Tang SJ. Anorectal bleeding: etiology, evaluation, and management (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:406-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Albuquerque A. Rubber band ligation of hemorrhoids: A guide for complications. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;8:614-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 8. | Su MY, Chiu CT, Lin WP, Hsu CM, Chen PC. Long-term outcome and efficacy of endoscopic hemorrhoid ligation for symptomatic internal hemorrhoids. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2431-2436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Madoff RD, Fleshman JW; Clinical Practice Committee, American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of hemorrhoids. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1463-1473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shanmugam V, Thaha MA, Rabindranath KS, Campbell KL, Steele RJ, Loudon MA. Rubber band ligation versus excisional haemorrhoidectomy for haemorrhoids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2005:CD005034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Su MY, Tung SY, Wu CS, Sheen IS, Chen PC, Chiu CT. Long-term results of endoscopic hemorrhoidal ligation: two different devices with similar results. Endoscopy. 2003;35:416-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schleinstein HP, Averbach M, Averbach P, Correa PAFP, Popoutchi P, Rossini LGB. Endoscopic band ligation for the treatment of hemorrhoidal disease. Arq Gastroenterol. 2019;56:22-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Xiong K, Zhao Q, Li W, Yao T, Su Y, Wang J, Fang H. Comparison of the long-term efficacy and safety of multiple endoscopic rubber band ligations in a single session for varying grades of internal hemorrhoids. Ir J Med Sci. 2023;192:2747-2753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wehrmann T, Riphaus A, Feinstein J, Stergiou N. Hemorrhoidal elastic band ligation with flexible videoendoscopes: a prospective, randomized comparison with the conventional technique that uses rigid proctoscopes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:191-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cazemier M, Felt-Bersma RJ, Cuesta MA, Mulder CJ. Elastic band ligation of hemorrhoids: flexible gastroscope or rigid proctoscope? World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:585-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Davis KG, Pelta AE, Armstrong DN. Combined colonoscopy and three-quadrant hemorrhoidal ligation: 500 consecutive cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1445-1449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fukuda A, Kajiyama T, Kishimoto H, Arakawa H, Someda H, Sakai M, Seno H, Chiba T. Colonoscopic classification of internal hemorrhoids: usefulness in endoscopic band ligation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:46-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dennison AR, Whiston RJ, Rooney S, Morris DL. The management of hemorrhoids. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:475-481. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Beppu K, Inokuchi K, Koyanagi N, Nakayama S, Sakata H, Kitano S, Kobayashi M. Prediction of variceal hemorrhage by esophageal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1981;27:213-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 608] [Cited by in RCA: 558] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Marschner IC, Gillett AC. Relative risk regression: reliable and flexible methods for log-binomial models. Biostatistics. 2012;13:179-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sobrado CW, de Almeida Obregon C, Sobrado LF, Bassi LM, Bacchi Hora JA, Silva E Sousa Júnior AH, Nahas SC, Cecconello I. The novel BPRST classification for hemorrhoidal disease: A cohort study and an algorithm for treatment. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2021;61:97-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/