Published online Dec 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i12.111872

Revised: August 18, 2025

Accepted: November 7, 2025

Published online: December 16, 2025

Processing time: 158 Days and 9.4 Hours

Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) accounts for up to 4% of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Argon plasma coagulation and radiofrequency ablation have been primary treatment modalities for patients with linear and punctate subtypes, with a newer trend of utilization of endoscopic band ligation (EBL). This study evaluates the outcomes of patients undergoing treatment for nodular GAVE. We hypothesize that patients treated initially with EBL will achieve higher rates of clinical remission with fewer endoscopic treatments and a shorter treat

To investigate the effects of EBL as an initial treatment therapy on outcomes asso

A total of 37 patients at a tertiary medical center with nodular GAVE were includ

Linear regression analysis displayed a positive relationship between the time interval from initial therapeutic esophagogastroduodenoscopy to first EBL treatment and overall treatment interval (t = 7.39, P < 0.001), as well as between the number of endoscopic treatments (t = 8.09, P < 0.001). Hemoglobin levels increased in both the initial EBL group (8.7 vs 11.4, P < 0.001) and the initial endoscopic thermal therapy group (8.6 vs 10.4, P = 0.042). Clinical remission rates were higher in the initial EBL group (90% vs 69% P = 0.041), with a non-significant trend of higher endoscopic remission rates (57.1% vs 37.5%, P = 0.270).

The observed trend favoring EBL, combined with its association with improved clinical remission and reduced treatment burden, supports its consideration as a preferred initial treatment approach.

Core Tip: Nodular gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) is a rare and treatment-resistant subtype of GAVE with limited data guiding optimal therapy. This retrospective study compares endoscopic band ligation (EBL) and endoscopic thermal therapy, including argon plasma coagulation and radiofrequency ablation, as initial treatments for nodular GAVE. Patients initially treated with EBL achieved significantly higher clinical remission rates, required fewer procedures, and had shorter treatment intervals. These findings suggest that EBL may be a more effective first-line treatment for nodular GAVE, offering improved outcomes and reduced treatment burden compared to traditional thermal modalities.

- Citation: Cooper JA, Statham E, Holyfield A, Shoreibah MG, Peter S. Initial treatment approaches for nodular gastric antral vascular ectasia: A comparison of endoscopic band ligation and thermal therapies. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(12): 111872

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i12/111872.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i12.111872

Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) is a disease characterized by vascular lesions in the gastric antrum that present with iron deficiency anemia and melena, accounting for 4% of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding[1]. GAVE is associated with a multitude of conditions, including cirrhosis, chronic kidney disease, systemic sclerosis, diabetes mellitus, and connective tissue disorders[2]. Unlike esophageal varices and portal hypertensive gastropathy, GAVE can occur independently of portal hypertension and is thought to be related to liver dysfunction, as evidenced by the resolution of GAVE and associated anemia after liver transplantation. Resolution of GAVE after liver transplantation is thought to be related to correction of hepatic dysfunction rather than portal hypertension, as GAVE can resolve even when portal hypertension persists after liver transplantation[3,4].

GAVE must be treated using different techniques than esophageal varices and portal hypertensive gastropathy, as it is unrelated to portal hypertension. Previous studies have shown that procedures to ameliorate portal hypertension, such as transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, failed to control bleeding from GAVE, substantiating the hypothesis that GAVE is not a product of portal hypertension[5]. Endoscopic band ligation (EBL) and endoscopic thermal therapies (ETT) such as argon plasma coagulation (APC) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) have proven to be efficacious and safe in the treatment of GAVE. EBL for GAVE involves the application of elastic bands directly on visible GAVE lesions, typically in a circumferential or linear pattern (dependent on phenotype). This process induces localized ischemia and fibrosis of dilated mucosal and submucosal capillaries of the gastric antrum, leading to ischemia and subsequent necrosis of the targeted tissue, whereas APC utilizes ionized argon gas to deliver electrical current to the mucosal surface to coagulate superficial mucosal vessels[6].

GAVE varies in appearance based on its gross endoscopic appearance[7]. Endoscopically, two variants of GAVE, the “watermelon stomach” and the “honeycomb stomach”, have been well described in the literature. More recently, a third variant, nodular GAVE, has been reported[2]. Nodular GAVE is characterized by the presence of nodular lesions in the gastric antrum, while watermelon stomach GAVE presents with characteristic longitudinal red stripes radiating from the pylorus. These two variants also differ histologically. Distinctive features of nodular GAVE include reactive epithelial hyperplasia, vascular ectasia, smooth muscle proliferation, and sometimes microvascular thrombi and fibrohyalinosis. Watermelon stomach GAVE, on the other hand, appears histologically as superficial fibromuscular hyperplasia, capillary ectasia, and microvascular thrombosis in the lamina propria, forming linear red stripes due to aligned ectatic vessels. Honeycomb GAVE appears similarly histologically to nodular GAVE but without microvascular fibrin and fibro

A retrospective chart review was conducted of all patients diagnosed endoscopically with GAVE between September 3, 2014, to September 30, 2024, at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, an academic tertiary center. The study population was identified by querying the institution’s Provation® MD database using the following diagnosis: GAVE. The dataset was further refined in the following stages: (1) Removing patients who did not undergo endoscopy; (2) Removing patients that were not treated endoscopically for GAVE; (3) Excluding patients with other causes of clinically significant intestinal bleeding; (4) Removing all patients with other subtypes of GAVE including watermelon and honeycomb; (5) Removing patients without ample laboratory data pre- and post-intervention; and (6) Removing patients who passed due to non-GAVE related complications before treatment interval conclusion. Patients were categorized based on initial endoscopic treatment modality (EBL vs ETT). Those treated endoscopically for nodular GAVE had either clinically significant anemia or intestinal bleeding.

Data was extracted through a review of the medical charts and stored in a secure, de-identified spreadsheet. Patient demographics included age, sex, race, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), comorbidities, and underlying cause of GAVE. Patients with nodular GAVE on endoscopy were included. The presence of intestinal bleeding related to GAVE on initial treatment esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was recorded, along with the severity grading: Mild, moderate, and severe. Data regarding time from initial nodular GAVE endoscopic treatment to subsequent EBL, number of EGDs with treatment performed in treatment interval, and overall treatment interval were collected. The presence of endoscopic remission, defined as either resolution of GAVE on EGD or endoscopic presence of GAVE not requiring treatment, was also noted. Additionally, endoscopic treatment modality type and frequency were recorded, including RFA, APC, EBL, yttrium-aluminum-garnet (YAG) laser, and clips. Data regarding the number of bands used during EBL was included. Laboratory studies were collected for each patient, including hemoglobin, serum creatinine, total serum bilirubin, serum sodium, serum albumin, and international internalized ratio. These values were collected at the time of the first endoscopic treatment and at least six weeks after the last endoscopic treatment. Iron studies, including ferritin and transferrin saturation, were included for some but not all patients. Pre- and post-treatment interval transfusion requirements were recorded along with pre- and post-treatment hospitalization rates. A transfusion requirement of

Primary outcomes included treatment interval, number of EGDs with endoscopic intervention, clinical remission, and endoscopic remission. Clinical remission was defined as an increase in post-treatment hemoglobin concentrations. Endoscopic remission was defined as either the resolution of GAVE on EGD or the endoscopic presence of GAVE not requiring treatment. Secondary outcomes included blood transfusion requirements, iron studies including ferritin and transferrin saturation, and hospitalization rates.

Data is presented using the mean for linear variables and the frequency percentage for categorical variables. The means of linear variables were compared between the two groups using a t-test and analysis of variance. Categorical variables were compared between the groups using χ2 and Fisher’s exact test. The analyses were two-sided and performed at a significance level of 5%. All statistical analyses were conducted by a biomedical statistician using IBM® SPSS® Statistics, version 30.

An initial Provation® MD database query for patients with an endoscopic diagnosis of GAVE produced 1163 cases. 37 patients were found to have nodular GAVE treated endoscopically after data refinement. 21 patients were initially treated with EBL (Initial EBL), and 16 patients were initially treated with endoscopic thermal therapy, including APC, RFA, or Nd: YAG laser (Initial ETT). 37 patients with nodular GAVE who received endoscopic treatment were identified. Among this group, 62% were males and 38% were females, with an average age at first EGD of 61.4 years. The racial distribution included 33 (89%) Caucasians, 3 African Americans (8%), and 1 Hispanic/Latino patient (3%). The average BMI at first EGD was 33.9. The mean hemoglobin A1c was 5.87, and 16% of patients had chronic kidney disease. Underlying causes of GAVE included metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis or metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (54.9%), alcoholic cirrhosis (32.4%), unspecified cirrhosis (10%), and unknown causes (2.7%) as seen in Table 1.

| Characteristic | n = 37 |

| Age | 61.4 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 38% |

| Male | 62% |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 89% |

| Non-Hispanic black | 8% |

| Latino | 3% |

| Other | 0% |

| MELD | |

| Pre-treatment | 14.5 |

| Post-treatment | 13.6 |

| Etiology | |

| MASLD/MASH | 55% |

| EtOH cirrhosis | 32% |

| Other | 13% |

| Comorbidities | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 35% |

| Chronic kidney disease | 16% |

| BMI | 33.9 |

| Hemoglobin A1c | 5.87 |

| Medications | |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 97% |

| Oral | 3% |

| Anticoagulation | 19% |

| Antiplatelet |

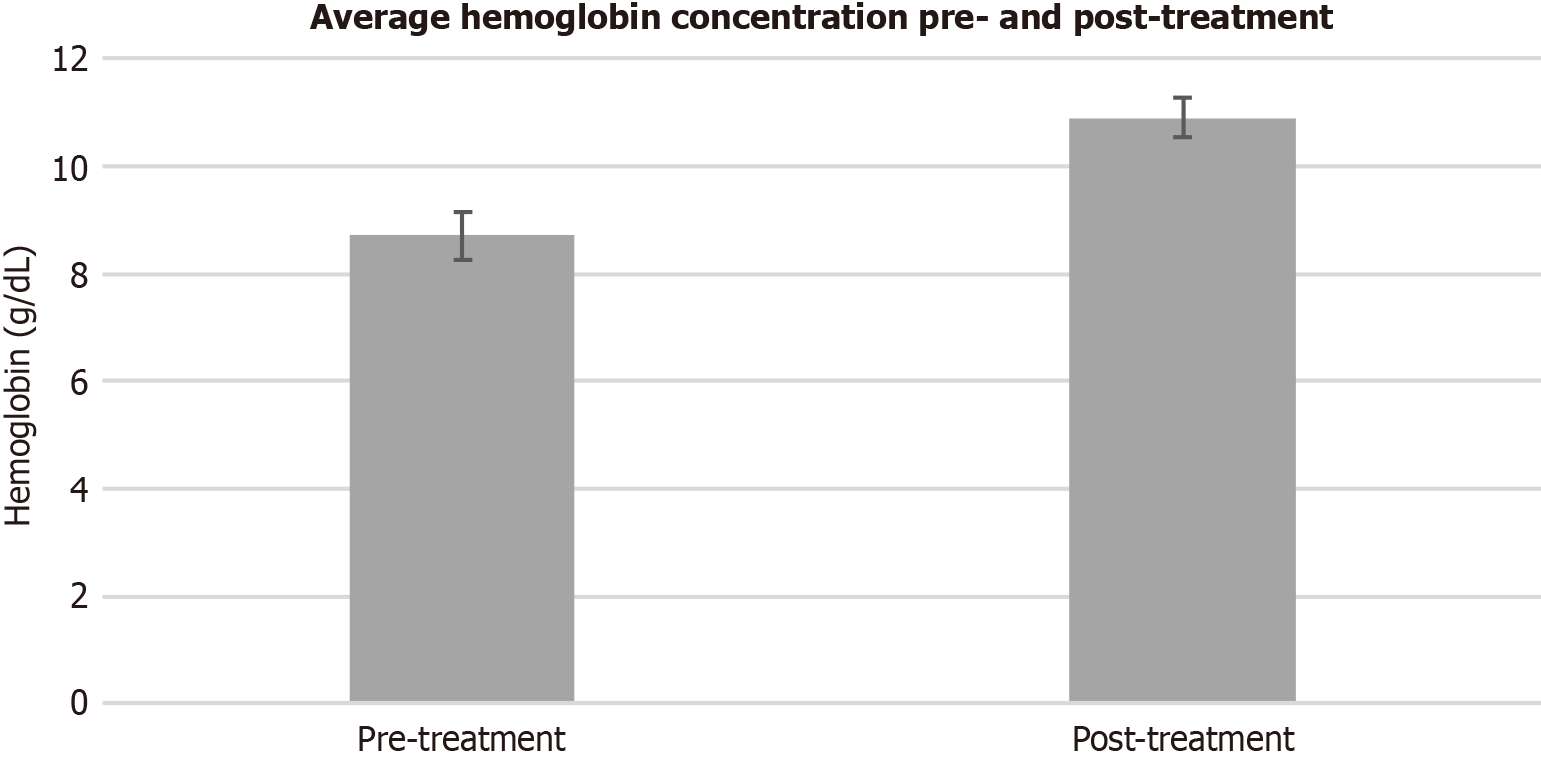

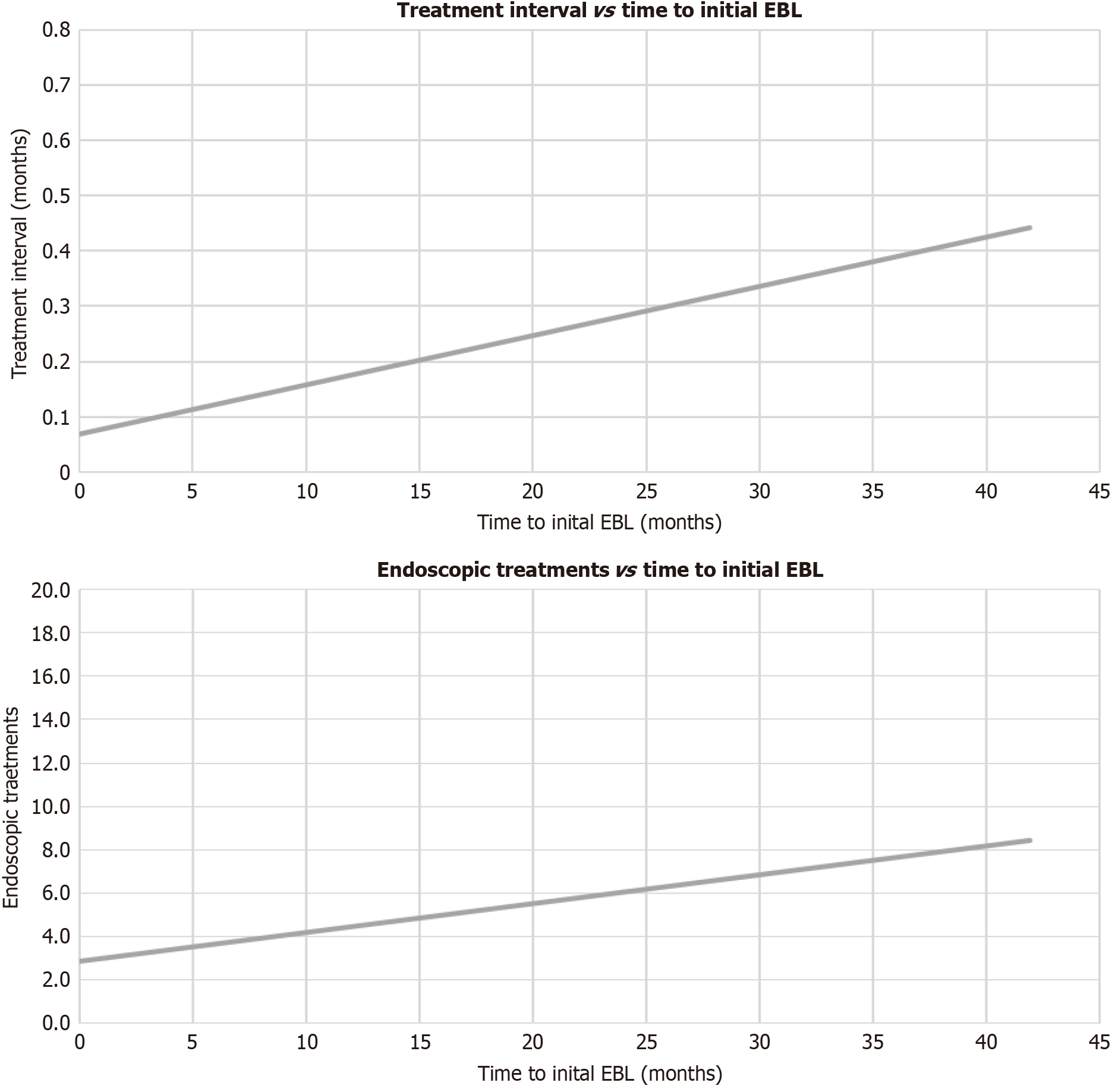

Clinical remission was achieved in 84% of patients. Mean hemoglobin concentrations increased during the treatment interval (8.7 vs 10.9, P < 0.001) as seen in Figure 1. Pre- and post-treatment ferritin levels (98.7 vs 90.2, P = 0.851) did not vary significantly, while serum transferrin saturation levels increased after the treatment interval (21.1 vs 47.8, P = 0.014). Overall reductions in transfusions (1.55 vs 0.19, P < 0.001) and hospitalizations for anemia (1.14 vs 0.24, P < 0.001) were also observed, as seen in Table 2. The model of end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores did not vary significantly after the treatment interval (14.49 vs 13.60, P = 0.552). The patients were treated over an average treatment interval of 499 days, receiving an average of 3.51 endoscopic treatments during the treatment interval. Linear regression analysis displayed a positive relationship between the time interval from initial therapeutic EGD to first EBL treatment and overall treatment interval (t = 7.39, P < 0.001), as well as between the number of endoscopic treatments (t = 8.09, P < 0.001), as shown in Figure 2. In short, earlier EBL leads to fewer endoscopic treatments, including ETT and EBL in a shorter treatment interval.

| Characteristic | P value | |

| Treatment interval (days) | 499 | |

| Number of EGDs | 3.51 | |

| Treatments | ||

| EBL | 1.46 | |

| No. bands deployed | 6.32 | |

| RFA | 0.51 | |

| APC | 1.49 | |

| Hemoglobin | < 0.001 | |

| Pre-treatment | 8.7 | |

| Post-treatment | 10.9 | |

| Ferritin | 0.851 | |

| Pre-treatment | 98.7 | |

| Post-treatment | 90.2 | |

| Transferrin saturation | 0.014 | |

| Pre-treatment | 21.1 | |

| Post-treatment | 47.8 | |

| Transfusions | < 0.001 | |

| Pre-treatment | 1.55 | |

| Post-treatment | 0.19 | |

| Hospitalizations | < 0.001 | |

| Pre-treatment | 1.14 | |

| Post-treatment | 0.24 | |

| Clinical remission rate | 84.0% | |

| Endoscopic remission rate | 48.7% |

Demographics, comorbidities, MELD scores, and proton pump inhibitor rates were consistent between the groups without statistically significant variance (refer to table: Sex, race, age, proton pump inhibitor, MELD, BMI, chronic kidney disease, on anticoagulants, on antiplatelet medications, hemoglobin A1c). On initial endoscopic exam, both the Initial EBL and Initial ETT groups had similar rates of bleeding (57% vs 44%, P = 0.435), and no correlation between initial endoscopic severity grades and initial treatment modalities was observed (P = 0.524). Both groups had comparable hemoglobin concentrations at the beginning of the treatment interval (8.7 ± 2.7 vs 8.6 ± 2.8, P = 0.949). However, higher post-treatment interval hemoglobin concentrations were observed in the Initial EBL group (11.4 ± 2.3) when compared to the initial ETT group (10.4 ± 2.3, P = 0.195). The initial EBL group displayed higher rates of clinical remission when compared to the initial ETT group (90% vs 69%, P = 0.041), along with higher rates of endoscopic remission (57.1% vs 37.5%, P = 0.270) as seen in Table 3. The initial EBL group also displayed lower rates of endoscopic recurrence after the first treatment than the initial ETT group (52% vs 81%, P = 0.032).

| Initial EBL | Initial ETT | P value | |

| Number | 21 | 16 | |

| Treatment interval (days) | 172 | 928 | 0.007 |

| Number of EGDs | 1.95 | 5.56 | 0.005 |

| Treatments | |||

| EBL | 1.67 | 1.19 | 0.349 |

| No. bands deployed | 1.85 | 1.92 | 0.063 |

| RFA | 0.05 | 1.12 | 0.010 |

| APC | 0.29 | 1.5 | 0.026 |

| Hemoglobin | |||

| Pre-treatment | 8.7 | 8.6 | 0.949 |

| Post-treatment | 11.4 | 10.4 | 0.195 |

| Transfusions | |||

| Pre-treatment | 1.04 | 0.33 | 0.176 |

| Post-treatment | 1.29 | 0.08 | 0.255 |

| Hospitalizations | |||

| Pre-treatment | 1.15 | 0.15 | 0.630 |

| Post-treatment | 2.15 | 0.25 | 0.092 |

| Clinical remission rate | 90% | 69% | 0.041 |

| Endoscopic remission rate | 57.1% | 37.5% | 0.270 |

When comparing treatment between the two groups, the initial EBL group had a shorter treatment interval (172 days vs 928 days, P = 0.013) and a lower number of endoscopic treatment sessions (1.95 vs 5.56, P = 0.009). The initial EBL group required fewer RFA sessions (0.05 vs 1.12, P = 0.010) and APC sessions (0.29 vs 1.5, P = 0.026) on a per-patient basis, but no statistical difference was observed in the number of EBL sessions (1.67 vs 1.19, P = 0.349) and bands deployed (1.85 vs 1.92, P = 0.063). EBL was required for clinical remission in 87.1% of all cases and was used as the final treatment modality, resulting in clinical remission in 80.6% of cases.

There were no clear distinguishing demographic factors when comparing the initial EBL and initial ETT groups, as seen in Table 4. No clear predicting factors that would help determine whether a patient would be treated with ETT or EBL were identified. When analyzing the ETT group, 75% of patients achieved clinical remission. EBL was required for clinical remission in 67% of these cases. 19% of patients in the entire cohort were treated with ETT alone, resulting in a 57% clinical remission rate with a staggering mean treatment interval of 831 days, as opposed to a clinical remission rate of 90% (P = 0.034) with a treatment interval of 421 days (P = 0.229) in patients treated with EBL. Treatment with EBL led to increasing odds of clinical remission (odds ratio = 6.75, confidence interval: 1.01-12.49; P = 0.05). These findings suggest that EBL should be considered when initially treating nodular GAVE and that EBL is necessary for achieving clinical remission in most cases.

| Initial EBL | Initial ETT | P value | |

| Number | 21 | 16 | |

| Age | 63.6 | 59.1 | 0.343 |

| Gender | 0.751 | ||

| Female | 43% | 31% | |

| Male | 57% | 69% | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.486 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 90% | 88% | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 5% | 12% | |

| Latino | 5% | 0% | |

| Other | 0% | 0% | |

| MELD | |||

| Pre-treatment | 14.9 | 14 | 0.531 |

| Post-treatment | 13.8 | 13.4 | 0.660 |

| Etiology | 0.639 | ||

| MASLD/MASH | 62% | 50% | |

| EtOH cirrhosis | 33% | 31% | |

| Other | 5% | 19% | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hyperlipidemia | 29% | 44% | 0.359 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 14% | 19% | 0.669 |

| BMI | 34.7 | 32.8 | 0.778 |

| Hemoglobin A1c | 5.86 | 5.88 | 0.952 |

| Medications | |||

| Proton pump inhibitor | |||

| Oral | 95% | 100% | 0.329 |

| Anticoagulation | 5% | 0% | 0.329 |

| Antiplatelet | 29% | 6% | 0.069 |

In this study, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of EBL compared to endoscopic thermal ETT, including APC, RFA, and Nd: YAG laser for the treatment of nodular GAVE. Our results showed that EBL was associated with statistically significant outcomes, including higher rates of clinical remission, shorter treatment intervals, and fewer endoscopic interventions compared to ETT. Patients in the initial EBL group also had higher post-treatment hemoglobin concentrations, fewer transfusions, and reduced hospitalization rates for anemia. Specifically, 90% of patients in the EBL group achieved clinical remission, compared to 69% in the ETT group, and the EBL group had a significantly shorter treatment interval (172 days vs 928 days, P = 0.013). These findings suggest that EBL may be more effective as a first-line treatment for nodular GAVE, contributing to faster resolution of symptoms and reduced need for repeated interventions.

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases recommends EBL and ETT for treatment of the vascular sequelae of portal hypertension, but does not mention treatment modalities for GAVE, as its pathogenesis is unrelated to portal hypertension[9]. Some studies suggest that it is a process related to factors such as metabolic syndrome, autoimmune diseases, and gastric mucosal injury[10]. Many treatment modalities have been trialed as treatment for GAVE, such as octreotide, which is commonly used in acute bleeds related to portal hypertension. However, case reports display mixed results on the efficacy of octreotide in the treatment of GAVE[11,12]. Other hormonal therapies, including estrogen and progesterone, have shown efficacy in treating GAVE in limited trials[13], likely by reducing the number of gastric mucosal vessels to control blood flow[14]. Nonetheless, recurrence is often seen when de-escalating the dose, as these hormonal therapies do not eradicate the lesion[15]. Surgical approaches such as gastric antrectomy have been trialed with some benefit in refractory cases[16].

Other more common therapies for GAVE include APC, RFA, Nd: YAG laser, and occasionally, the use of endoscopic clips, although many of these treatments have been met with mixed results. APC has been shown to provide symptomatic relief in some cases, but its effects may be transient, leading to recurrent bleeding and a need for further interventions. RFA has also demonstrated efficacy in controlling bleeding. However, this requires multiple sessions, and long-term effectiveness remains uncertain[17]. In our study, patients who initially received ETT often required EBL later in their treatment course, highlighting the limitations of ETT as a monotherapy.

EBL has been established as a safe and effective long-term treatment for GAVE. When compared to APC, EBL has lower rates of endoscopic recurrence (50%), correlating with our findings (52% endoscopic recurrence)[18]. A recent prospective, randomized study of 88 patients revealed that patients with GAVE treated with EBL had higher rates of clinical remission and lower transfusion requirements in shorter treatment intervals when compared to APC. Complication rates were similar between patients treated with APC and EBL[19]. While abundant data and studies display the effectiveness of endoscopic treatments of GAVE, there is a paucity of data in regards to treatment of nodular GAVE.

Nodular GAVE, a distinct subtype characterized by prominent nodules within the gastric antrum, is often misdiagnosed as benign antral nodular and inflammatory polyps[20]. It presents a particularly challenging therapeutic scenario due to its propensity for recurrent bleeding. Treatment strategies for nodular GAVE have been less studied compared to the more common diffuse or “watermelon stomach” forms of GAVE. Our study is unique in its focus on nodular GAVE. The results suggest that EBL is a highly effective initial treatment, with a significantly lower treatment interval compared to ETT. The high rate of clinical remission in our cohort further underscores the utility of EBL in this subgroup of patients, where more frequent treatments are often required to manage recurrent bleeding.

There are several limitations to this study. Data collection was reliant on the completeness of patient records, and some patients were excluded due to missing laboratory or clinical data. Certain outcome data, such as serum iron studies, oral iron supplementation rates, and iron transfusion rates, were not analyzed due to a lack of patient data. Future studies are needed to investigate the effect of EBL on serum iron levels and iron transfusion rates. Additionally, our study was conducted at a single tertiary care center, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other healthcare settings. The sample size, while adequate for the purpose of this study, is relatively small and may not fully capture the variability in treatment outcomes across a larger, more diverse cohort. Future prospective multicenter studies are warranted to validate these findings and further explore the long-term outcomes of EBL in patients with nodular GAVE.

In conclusion, our study suggests that EBL as the initial treatment for nodular GAVE may lead to higher rates of clinical remission, shorter treatment intervals, and fewer EGDs compared to ETT. While the difference in endoscopic remission rates did not reach statistical significance, the observed trend favoring EBL, combined with its association with improved clinical remission and reduced treatment burden, supports its consideration as a preferred initial treatment approach. Further prospective studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to confirm these findings.

Shajan P (The University of Alabama at Birmingham) kindly supported this work.

| 1. | Dulai GS, Jensen DM, Kovacs TO, Gralnek IM, Jutabha R. Endoscopic treatment outcomes in watermelon stomach patients with and without portal hypertension. Endoscopy. 2004;36:68-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Selinger CP, Ang YS. Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE): an update on clinical presentation, pathophysiology and treatment. Digestion. 2008;77:131-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Vincent C, Pomier-Layrargues G, Dagenais M, Lapointe R, Létourneau R, Roy A, Paré P, Huet PM. Cure of gastric antral vascular ectasia by liver transplantation despite persistent portal hypertension: a clue for pathogenesis. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:717-720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Allamneni C, Alkurdi B, Naseemuddin R, McGuire BM, Shoreibah MG, Eckhoff DE, Peter S. Orthotopic liver transplantation changes the course of gastric antral vascular ectasia: a case series from a transplant center. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:973-976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Spahr L, Villeneuve JP, Dufresne MP, Tassé D, Bui B, Willems B, Fenyves D, Pomier-Layrargues G. Gastric antral vascular ectasia in cirrhotic patients: absence of relation with portal hypertension. Gut. 1999;44:739-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Garg A, Moond V, Bidani K, Garg A, Broder A, Mohan BP, Adler DG. Endoscopic band ligation versus argon plasma coagulation in the treatment of gastric antral vascular ectasia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2025;101:1100-1109.e13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Thomas A, Koch D, Marsteller W, Lewin D, Reuben A. An Analysis of the Clinical, Laboratory, and Histological Features of Striped, Punctate, and Nodular Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63:966-973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bauer M, Morales-Orcajo E, Klemm L, Seydewitz R, Fiebach V, Siebert T, Böl M. Biomechanical and microstructural characterisation of the porcine stomach wall: Location- and layer-dependent investigations. Acta Biomater. 2020;102:83-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kaplan DE, Ripoll C, Thiele M, Fortune BE, Simonetto DA, Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J. AASLD Practice Guidance on risk stratification and management of portal hypertension and varices in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2024;79:1180-1211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 116.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Smith E, Davis J, Caldwell S. Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia Pathogenesis and the Link to the Metabolic Syndrome. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2018;20:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Brijbassie A, Osaimi AA, Powell SM. Hormonal Effects on Nodular GAVE. Gastroenterology Res. 2013;6:77-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Barbara G, De Giorgio R, Salvioli B, Stanghellini V, Corinaldesi R. Unsuccessful octreotide treatment of the watermelon stomach. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;26:345-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | van Cutsem E, Rutgeerts P, Vantrappen G. Treatment of bleeding gastrointestinal vascular malformations with oestrogen-progesterone. Lancet. 1990;335:953-955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Panés J, Casadevall M, Fernández M, Piqué JM, Bosch J, Casamitjana R, Cirera I, Bombí JA, Terés J, Rodés J. Gastric microcirculatory changes of portal-hypertensive rats can be attenuated by long-term estrogen-progestagen treatment. Hepatology. 1994;20:1261-1270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Manning RJ. Estrogen/progesterone treatment of diffuse antral vascular ectasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:154-156. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Frasconi C, Charachon A, Perrin H. Gastric antral vascular ectasia unresponsive to endoscopic treatment requiring antrectomy. J Visc Surg. 2014;151:415-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | McCarty TR, Rustagi T. Comparative Effectiveness and Safety of Radiofrequency Ablation Versus Argon Plasma Coagulation for Treatment of Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;53:599-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Eccles J, Falk V, Montano-Loza AJ, Zepeda-Gómez S. Long-term follow-up in patients with gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) after treatment with endoscopic band ligation (EBL). Endosc Int Open. 2019;7:E1624-E1629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Elhendawy M, Mosaad S, Alkhalawany W, Abo-Ali L, Enaba M, Elsaka A, Elfert AA. Randomized controlled study of endoscopic band ligation and argon plasma coagulation in the treatment of gastric antral and fundal vascular ectasia. United European Gastroenterol J. 2016;4:423-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Aryan M, Jariwala R, Alkurdi B, Peter S, Shoreibah M. The misclassification of gastric antral vascular ectasia. J Clin Transl Res. 2022;8:218-223. [PubMed] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/