Published online Nov 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i11.110436

Revised: July 27, 2025

Accepted: October 10, 2025

Published online: November 16, 2025

Processing time: 161 Days and 7.8 Hours

Gastric adenoma is widely acknowledged as a premalignant lesion that can pro

To assess the subtype-specific risk factors and outcomes of endoscopic resection (ER) for gastric adenomas.

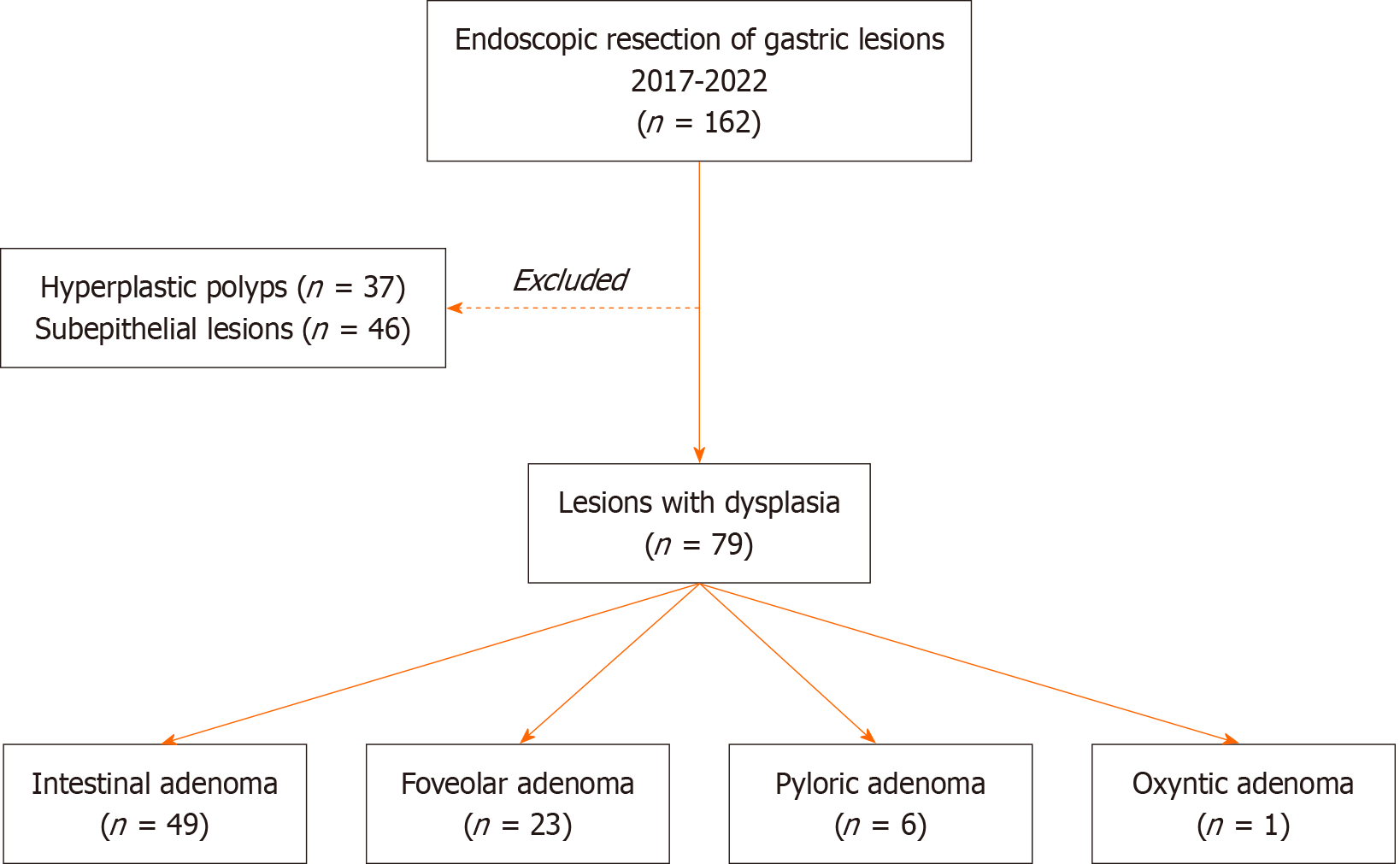

This is a retrospective cohort study. Among 162 patients who underwent ER for gastric lesions larger than 10 mm between 2017 and 2022, 79 patients with gastric adenomas were included. Hyperplastic polyps (n = 37) and subepithelial lesions (n = 46) were excluded. Logistic regression and survival analyses were conducted.

The 79 patients (mean age 68.1 years; 65% male) had adenoma subtypes: 62% intestinal, 29% foveolar, 8% pyloric, and 1% oxyntic. The mean follow-up was 26 months. Intestinal adenoma was strongly linked to a family history of gastric adenocarcinoma and atrophic gastritis (P < 0.001); foveolar adenoma was significantly associated with intestinal metaplasia (P < 0.001). Pyloric adenomas had the largest polyp size (P < 0.001). Recurrence rates were 8%, 17%, and 17% for the respective subtypes (P = 0.07), with no significant difference in the meantime to recurrence

This study identifies distinct risk factor profiles for different subtypes of gastric adenomas and independent recurrence predictors post-ER, underscoring the importance of subtype-specific tailored risk assessment and surveillance strategies.

Core Tip: Gastric adenomas exhibit subtype-specific characteristics; intestinal adenomas linked to family history of gastric adenocarcinoma and atrophic gastritis, foveolar adenomas associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and intestinal metaplasia, and pyloric adenomas presenting as large multiple polyps. Understanding the unique clinicopathological features of different subtypes of gastric adenomas helps to implement risk-stratified surveillance strategies and address modifiable factors like Helicobacter pylori infection to reduce recurrence rates.

- Citation: El-Domiaty N, Beuvon F, Carpentier-Pourquier M, Ibrahim W, Oumrani S, Doumbe-Mandengue P, Belle A, Chaussade S, Pellat A, Shiha G, Coriat R, Barret M. Subtype-specific risk factors for gastric adenomas and independent predictors of recurrence after endoscopic resection. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(11): 110436

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i11/110436.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i11.110436

Gastric adenoma is widely acknowledged as a premalignant lesion that can progress to gastric adenocarcinoma[1]. Much of the existing literature groups all adenoma subtypes together, categorizing them based on features such as tubular, villous, or mixed structures, as well as flat or depressed morphologies[1-3]. However, gastric adenomas can be classified into four distinct types. Intestinal adenomas, which account for over half of all gastric adenomas, are characterized by foci of intestinal epithelium and are often associated with atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia[4]. The foveolar type, the second most common subtype, exhibits dysplasia but is generally considered less aggressive than intestinal adenomas and is rarely linked to high-grade dysplasia (HGD) or adenocarcinoma[5]. Foveolar adenomas typically develop in normal mucosal tissue and are frequently associated with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)[4]. Pyloric-type adenomas, similar to intestinal-type adenomas, are associated with an aggressive clinical course and arise in the setting of atrophic gastritis[6]. Oxyntic gland adenomas, previously regarded as rare precursors to gastric adenocarcinoma with specific chief cell differentiation, have not been reported to recur or metastasize to date[6].

The diagnosis of gastric adenoma is typically made through endoscopic biopsy sampling. However, due to discrepancies between biopsy results and findings from resected specimens, complete endoscopic resection (ER) of all gastric adenomas is recommended[7-10]. The incidence of synchronous or metachronous recurrence after ER ranges from 3% to 20.9%[11], necessitating mandatory endoscopic surveillance at three months post-resection and annually thereafter[12,13]. To our knowledge, few Western studies have comprehensively investigated gastric adenomas[12,14]. This study aims to evaluate the prevalence, potential risk factors, and outcomes of endoscopic management for the different subtypes of gastric adenoma.

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at a French tertiary referral center for digestive endoscopy. Data were obtained from a prospectively collected database of consecutive patients who underwent ER for gastric lesions between 2017 and 2022. The data collected included patient demographics, body mass index (BMI), history of comorbidities, family history of cancer, personal history of gastric neoplasia, history of drug intake [statin, proton pump inhibitor (PPI), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) and aspirin], and endoscopic (number, size and location) and histopathological features [histological subtype, chronic gastritis, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection]. Data regarding the type of endoscopic treatment, either endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) or endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), and post ER recurrence (location, number, size, histological type and time to recurrence after resection) were also collected.

Data were obtained from electronic patient records following approval by the local hospital ethics committee (reference number: AAA-2023-09011). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and adhered to the principles of good clinical practice.

At our endoscopy unit, ER techniques were tailored according to lesion characteristics and subtype. Intestinal adenomas (often antral, with atrophic gastritis) required careful complete resection margins due to adenocarcinoma risk. Foveolar adenomas (frequently multiple, Paris 0-IIa+IIc) necessitated meticulous mapping and staged R0 resection. Larger, Paris 0-Ippyloric adenomas often require ESD.

Magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (NBI) was utilized to assess micro-surface patterns, particularly for lesions with indeterminate borders. Foveolar adenomas typically demonstrated regular micro-surface patterns with fine granular or homogeneous appearances, while intestinal adenomas often showed irregular micro-surface patterns consistent within intestinal metaplasia with disrupted microvascular architecture. Pyloric adenomas exhibited characteristic tubular or papillary micro-surface patterns with regular microvascular patterns. Oxyntic adenomas, represented by a single case, showed homogeneous micro surface patterns with regular microvascular architecture[15,16].

Delineating resection margins for foveolar adenomas is challenging due to their subtle endoscopic appearance and similarity to hyperplastic polyps. To optimize R0 resection, we employed careful pre-resection assessment using magnifying NBI to identify demarcation lines, ensuring a 2-3 mm safety margin. En bloc resection was performed when feasible (especially for lesions > 20 mm), while larger lesions underwent piecemeal resection with precise margin mapping. Post-resection assessment with white light and NBI confirmed complete removal, with further resection if suspicious margins persisted[17].

The follow-up period was calculated from the date of ER to the last follow-up visit, the date of death, or the study's conclusion (January 31, 2024). All patients were scheduled for follow-up endoscopic evaluations at 3-or 6-months post-ER, followed by additional examinations every 6 months and annually thereafter.

Residual adenoma was identified as the presence of a new adenoma detected within the first 3-6 months following ER. In contrast, recurrent adenoma was defined as the detection of an adenoma occurring more than 6 months after the last ER. Recurrence could manifest either at the same location as the previously resected adenoma (local recurrence) or at a different site distant from the primary adenoma (metachronous recurrence).

All the statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 26 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) and R software version 4.3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Categorical variables are presented as percentages and were compared via the χ2 test with Fisher’s correction. Continuous variables are expressed as the means with SD and were compared via ANOVA. Recurrence and residual rates were assessed via the Kaplan-Meier method and compared via the log-rank test. Statistical significance was accepted with a

Of the 162 patients who underwent endoscopic ER for gastric lesions between 2017 and 2022, 79 were included in this study following diagnosis of gastric adenoma. Patients with hyperplastic polyps (n = 37) or subepithelial lesions (n = 46) were excluded. The 79 patients were classified into four groups based on histological subtypes of gastric adenoma: Intestinal (n = 49), foveolar (n = 23), pyloric (n = 6), and oxyntic (n = 1) (Figure 1).

The clinical characteristics of these 79 patients at the time of gastric adenoma diagnosis is summarized in Table 1. Patients with oxyntic adenoma were excluded from statistical analysis to avoid bias. The majority of patients were male (64.6%) with a mean BMI of 24.9 ± 3.9 kg/m2. Cardiovascular diseases were the most common comorbidity (58.2%), followed by malignancies (27.8%) and diabetes mellitus (21.5%). Histories of PPI and NSAID/aspirin intake were recorded in 94.9% and 68.4% of patients, respectively (Table 1).

| n (%) | |

| Gender | |

| Male | 51 (64.6) |

| Female | 28 (35.4) |

| Mean age, years | 68.1 ± 14.6 |

| Mean BMI, kg/m2 | 24.9 ± 3.9 |

| Comorbidities | |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 46 (58.2) |

| Malignancy | 22 (27.8) |

| Diabetes | 17 (21.5) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4 (5.1) |

| Morbid obesity | 3 (3.8) |

| Cirrhosis | 2 (2.5) |

| History of PPI intake | 75 (94.9) |

| History of NSAID/Aspirin intake | 54 (68.4) |

| History of alcohol abuse | 39 (49.4) |

| History of smoking | 34 (43.0) |

| History of statin intake | 26 (32.9) |

| Hereditary predisposition | |

| FAP | 4 (5.1) |

| Peutz Jeghers/juvenile polyposis | 2 (2.5) |

| Others | 2 (2.5) |

| Personal history of gastric neoplasia | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 14 (17.7) |

| Adenoma | 7 (8.9) |

| Family history | |

| Gastric adenocarcinoma | 8 (10.1) |

| Colorectal cancer | 5 (6.3) |

| Other cancers | 3 (3.8) |

Eight patients had hereditary predispositions to gastric neoplasia: Four (5.1%) with FAP, two (2.5%) with juvenile polyposis, and two (2.5%) with other hereditary predispositions. Personal histories included gastric adenocarcinoma in 14 patients (17.7%) and gastric adenoma in seven patients (8.9%) (Table 1).

The majority of the patients (86.1%) had a single lesion. The mean size of the resected specimens was 31.9 ± 19.2 mm. The most common location for gastric adenoma was the antrum (36.7%), followed by the body (greater curvature: 22.8% and lesser curvature: 10.1%). Approximately 27.8% of the adenomas were Paris classification 0-IIa, and 25.4% of them were Paris classification 0-IIa+IIc. Half of the lesions (51.9%) were reddish in color. Most of the lesions (82.3%) were resected

| n (%) | |

| Baseline endoscopic characteristics: | |

| Number of lesions | |

| 1/2/≥ 3 | 68 (86.1)/5 (6.3)/6 (7.6) |

| Mean size, mm | 31.9 ± 19.2 |

| Location | |

| Cardia/fundus | 21 (26.6) |

| Greater curvature | 18 (22.8) |

| Lesser curvature | 8 (10.1) |

| Antrum | 29 (36.7) |

| Pylorus | 3 (3.8) |

| Gross morphology (Paris classification) | |

| 0-Ip | 10 (12.7) |

| 0-Is | 17 (21.5) |

| 0-IIa | 22 (27.8) |

| 0-IIb | 2 (2.5) |

| 0-IIc | 6 (7.6) |

| 0-IIa+IIc | 20 (25.4) |

| 0-Is+IIc | 2 (2.5) |

| Color | |

| Reddish | 41 (51.9) |

| Same as background mucosa | 20 (25.3) |

| Ulcerated/erosive | 16 (20.3) |

| Whitish | 2 (2.5) |

| Treatment | |

| EMR | 14 (17.7) |

| ESD | 65 (82.3) |

| Histopathological characteristics: | |

| Histological subtype | |

| Intestinal | 49 (62.0) |

| Foveolar | 23 (29.1) |

| Pyloric | 6 (7.6) |

| Oxyntic | 1 (1.3) |

| Helicobacter pylori infection | |

| Negative | 56 (70.9) |

| Past infection | 18 (22.8) |

| Current infection | 4 (5.1) |

| Mean size of resected specimen, mm | 37.7 ± 34.3 |

| Underlying stomach | |

| Normal | 11 (13.9) |

| Atrophic gastritis | 39 (49.4) |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 29 (36.7) |

| Worst histology | |

| LGD | 22 (27.8) |

| HGD | 18 (22.8) |

| Intramucosal adenocarcinoma (T1a) | 21 (26.6) |

| Submucosal carcinoma (T1b) | 18 (22.8) |

| Resection completeness | |

| Histologically complete (R0) | 73 (92.4) |

| Piecemeal | 5 (6.3) |

| Failed endoscopic resection | 1 (1.3) |

Active H. pylori infection was histologically diagnosed in four patients (5.1%), 56 patients (70.9%) were not infected, and 18 patients (22.8%) had a history of eradicated H. pylori infection. Histopathologic examination of the underlying gastric mucosa revealed normal mucosa in 11 patients (13.9%), whereas atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia were observed in 49.4% and 36.7% of the patients, respectively.

Histopathologic examination of the lesions revealed intestinal adenoma in 49 (62.0%) lesions, foveolar adenoma in

Patients were followed for an average of 26.3 ± 21.8 months. Residual adenoma, detected within six months of resection, occurred in four patients (5.1%). These patients had initial HGD, with two undergoing piecemeal EMR and two undergoing complete (R0) ESD. Local recurrence was observed in nine patients (11.4%), with only one patient (1.3%) experiencing a metachronous recurrence. The average time to recurrence was 18.0 ± 15.4 months.

Among the 10 patients with recurrent lesions, three patients experienced more than two recurrences. Histological analysis of the recurrent lesions revealed LGD in 8.9%, HGD in 3%, and intramucosal adenocarcinoma in 1.3% of the patients (Table 3).

| n (%) | |

| Mean follow-up, months, mean ± SD | 26.3 ± 21.8 |

| Early follow-up (3-6 months) | |

| Residual adenoma | 4 (5.1) |

| Management of residual adenoma | |

| EMR | 2 (2.5) |

| ESD | 2 (2.5) |

| Late follow up (> 6 months) | |

| Mean time to recurrence ± SD, months | 18.0 ± 15 |

| Recurrent adenoma | |

| Local | 9 (11.4) |

| Metachronous | 1 (1.3) |

| Management of recurrent adenoma | |

| EMR | 6 (7.6) |

| ESD | 4 (5.1) |

| Pathology of recurrent adenoma | |

| LGD | 7 (8.9) |

| HGD | 2 (2.5) |

| Intramucosal adenocarcinoma (T1a) | 1 (1.3) |

The sex, mean BMI and comorbidities were comparable among the three groups, and the mean age was significantly greater in the intestinal group than in the other two groups (71.1 ± 12.9 years vs 63.8 ± 15.7 years vs 58.2 ± 17.9 years,

There was no significant difference across the three subgroup groups in either personal history of gastric neoplasia

| Intestinal (n = 49) (%) | Foveolar (n = 23) (%) | Pyloric (n = 6) (%) | P value | |

| Patients characteristics: | ||||

| Gender (male) | 69.40 | 65.20 | 33 | 0.215 |

| Mean age, years | 71.1 ± 12.9 | 63.8 ± 15.7 | 58.2 ± 17.9 | 0.031 |

| Mean BMI, kg/m2 | 25.3 ± 3.2 | 24.1 ± 4.8 | 25.2 ± 6.2 | 0.564 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes | 22.40 | 21.70 | 16.70 | 0.94 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 55.10 | 73.90 | 33.30 | 0.142 |

| Morbid obesity | 6.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.389 |

| Malignancy | 24.50 | 30.40 | 50.00 | 0.43 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 6.10 | 4.30 | 0.00 | 0.79 |

| Cirrhosis | 2.00 | 0.00 | 16.70 | 0.069 |

| History of PPI intake | 91.80 | 100 | 100.00 | 0.531 |

| History of NSAID/Aspirin | 65.30 | 82.60 | 33.30 | 0.046 |

| History of statin | 38.80 | 26.10 | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| Hereditary predisposition | ||||

| FAP | 2.00 | 8.70 | 16.70 | 0.106 |

| Juvenile polyposis | 0.00 | 8.70 | 0.00 | |

| Personal history | 0.106 | |||

| Gastric neoplasia | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 22.40 | 4.30 | 33.30 | |

| Adenoma | 4.10 | 13 | 33.30 | |

| Family history | 0.006 | |||

| Gastric adenocarcinoma | 14.30 | 4.30 | 0 | |

| Colorectal cancer | 6.10 | 8.70 | 0 | |

| Other cancers | 0 | 4.30 | 33.30 | |

| Baseline endoscopic findings: | ||||

| Number of lesions | < 0.001 | |||

| 1/2/≥ 3 | 93.9/6.1/0 | 78.3/0/21.7 | 66.7/33.3/ 0 | |

| Mean size, mm | 27.5 ± 14.6 | 34.6 ± 18.1 | 59.2 ± 33.2 | < 0.001 |

| Location | 0.048 | |||

| Cardia/Fundus | 24.50 | 30.40 | 33.30 | |

| Greater curvature | 14.30 | 34.80 | 33.30 | |

| Lesser curvature | 8.20 | 17.40 | 0.00 | |

| Antrum | 48.90 | 17.40 | 16.70 | |

| Pylorus | 4.10 | 0.00 | 16.70 | |

| Gross morphology | 0.046 | |||

| (Paris classification) | ||||

| 0-Ip | 2.00 | 26.10 | 33.30 | |

| 0-Is | 18.40 | 21.70 | 50.00 | |

| 0-IIa | 32.70 | 21.70 | 16.70 | |

| 0-IIb | 4.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 0-IIc | 10.20 | 4.30 | 0.00 | |

| 0-IIa+IIc | 28.60 | 26.10 | 0.00 | |

| 0-Is+IIc | 4.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Color | 0.269 | |||

| Same as background mucosa | 32.70 | 17.40 | 0.00 | |

| Whitish | 2.00 | 4.30 | 0.00 | |

| Reddish | 42.90 | 60.90 | 83.30 | |

| Ulcerated/Erosive | 22.40 | 17.40 | 16.70 | |

| Treatments | ||||

| EMR/ESD | 6.1/93.9 | 34.8/65.2 | 33.3/66.7 | 0.005 |

| Histological characteristics: | ||||

| Active Helicobacter pylori | 4.10 | 8.70 | 0.00 | 0.373 |

| Underlying stomach | ||||

| Atrophic gastritis | 67.30 | 13 | 50 | < 0.001 |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 26.50 | 69.60 | 0.00 | |

| Worst histology | 0.411 | |||

| LGD | 20.40 | 30.40 | 50 | |

| HGD | 18.40 | 26.10 | 33.30 | |

| Early gastric adenocarcinoma | 57.10 | 43.50 | 16.70 | |

| T1a | 34.70 | 17.40 | 0.00 | |

| T1b | 22.40 | 26.10 | 16.70 | |

| Mean size of resected specimen, mm | 34.1 ± 14.0 | 47.0 ± 58.0 | 35.0 ± 23.0 | 0.349 |

| Histologically complete resection (R0) | 89.80 | 91.30 | 100 | 0.935 |

| Clinical outcomes: | ||||

| Mean follow-up, months | 24.9 ± 21.9 | 26.3 ± 21.4 | 43.1 ± 27.1 | 0.613 |

| Early follow-up | ||||

| Residual adenoma | 2.00 | 13.00 | 0.00 | 0.184 |

| Management: EMR/ESD | 0.0/2.0 | 8.7/4.3 | 0.0/0.0 | 0.205 |

| Late follow up (recurrence) | ||||

| Mean time to recurrence, months | 21.4 ± 16.8 | 19.9 ± 17.3 | 14.3 | 0.833 |

| Local/metachronous | 6.1/2.0 | 17.4/0.0 | 16.7/0.0 | 0.07 |

| Management: EMR/ESD | 2.0/6 | 17.4/0.0 | 0.0/16.7 | 0.044 |

| Pathology | 0.284 | |||

| LGD | 2.00 | 17.40 | 16.70 | |

| HGD | 4.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| T1a | 2.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

With respect to the baseline endoscopic findings, foveolar adenomas were significantly associated with multiple (≥ 3) lesions (P < 0.001) and Paris 0-IIa+IIc classification (P = 0.046). Moreover, the mean size of the largest polyp was significantly greater in the pyloric group (P < 0.001).

Compared with the other two groups, the histological examination of the surrounding mucosa revealed more atrophic gastritis in the intestinal adenoma group (33/49 patients, 67%), whereas the foveolar adenoma group was more frequently associated with intestinal metaplasia (16/23 patients, 70%) (P < 0.001) (Table 4).

ESD was significantly more frequently used in the intestinal adenoma group (94% vs 65% vs 67%, P = 0.005, for the intestinal, foveolar and pyloric adenoma groups, respectively), with variable rates of histologically complete (R0) resection (90% vs 29% vs 100%, P = 0.935, for the intestinal, foveolar and pyloric adenoma groups, respectively).

Early gastric adenocarcinoma (T1a and T1b) was observed in 28/49 (57.1%) of the intestinal adenomas, 10/23 (43.5%) of the foveolar adenomas, and 1/6 (16.7%) of the pyloric adenomas (P = 0.411) (Table 4).

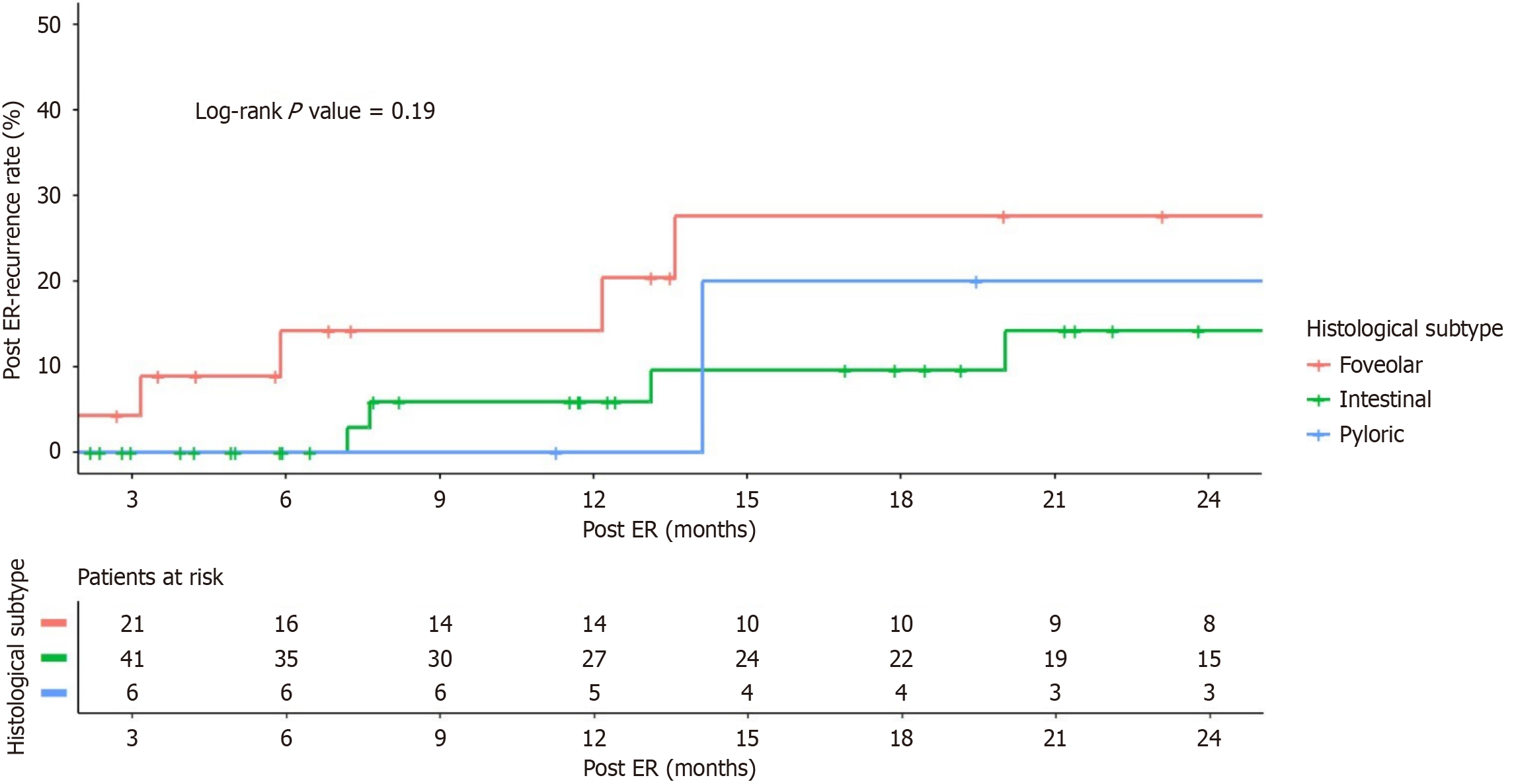

The post ER outcomes were comparable among the three groups, with overall recurrence rates of 8.1% for intestinal adenomas, 17.4% for foveolar adenomas, and 16.7% for pyloric adenomas (P = 0.070). The mean time to recurrence among the three groups was also comparable (21.4 ± 16.8 months vs 19.9 ± 17.3 months vs 14.3 months, P = 0.833, for the intestinal, foveolar and pyloric adenoma groups, respectively) (Table 4).

Ten patients (9 patients with intestinal adenoma and 1 patient with foveolar adenoma) had infiltrating adenocarcinoma and were referred for post-ESD surgery; 6 (7.6%) patients underwent total gastrectomy, 3 (3.8%) underwent partial gastrectomy, and 1 (1.3%) underwent Ivor Lewis esophagectomy.

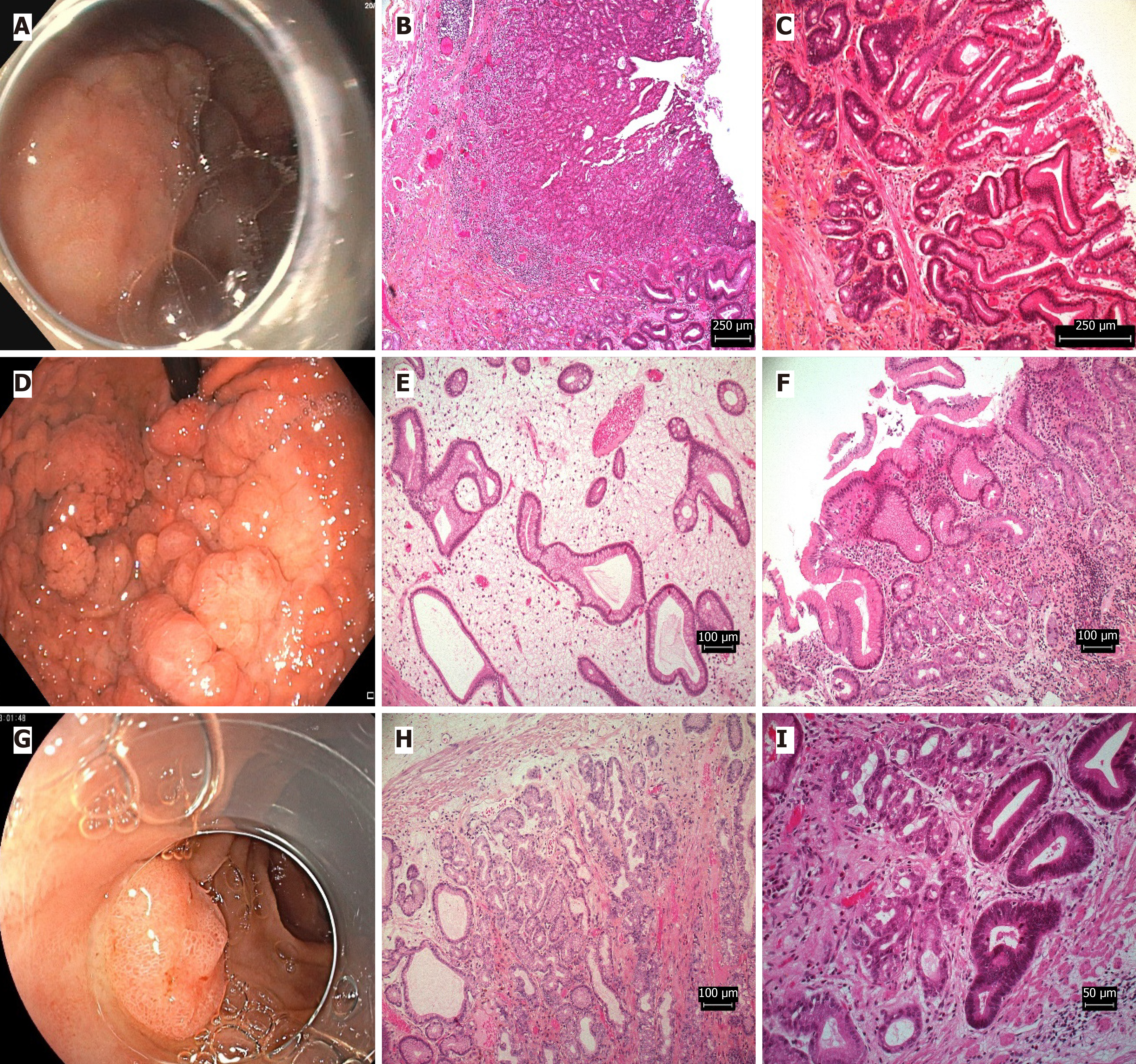

Intestinal adenoma: Age ≥ 65 years (OR = 3.224; 95%CI: 1.198-4.680), a history of statin intake (OR = 1.161; 95%CI: 1.161-3.255), and a family history of gastric adenocarcinoma (OR = 1.641; 95%CI: 1.38-3.995) were identified as potential risk factors associated with intestinal adenoma. In addition to atrophic gastritis (OR 1.831; 95%CI: 1.560-4.329), a single lesion (OR = 1.736; 95%CI: 1.470-4.163), an antral location of the lesion (OR = 2.366; 95%CI: 2.06-5.235) and a Paris 0-IIa morphology (OR = 2.134; 95%CI: 1.840-4.848) were detected (Table 5; Figure 2A-C).

| B-estimate | P value | Odds ratio | 95%CI | |

| Potential risk factors for different subtypes of gastric adenomas | ||||

| Intestinal adenoma: | ||||

| Age ≥ 65 years | 1.171 | 0.021 | 3.224 | (1.198-4.680) |

| History of statin intake | 0.149 | < 0.001 | 1.161 | (1.1-3.255) |

| Family history of gastric adenocarcinoma | 0.495 | < 0.001 | 1.641 | (1.38-3.995) |

| Single polyp | 0.551 | < 0.001 | 1.736 | (1.47-4.163) |

| Antrum as location | 0.861 | < 0.001 | 2.366 | (2.06-5.235) |

| Atrophic gastritis | 0.605 | < 0.001 | 1.831 | (1.56-4.329) |

| Morphology as Paris classification 0-IIa | 0.758 | < 0.001 | 2.134 | (1.84-4.848) |

| Foveolar adenoma: | ||||

| BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2 | 0.105 | < 0.001 | 1.111 | (1.03-3.656) |

| History of NSAID intake | 0.623 | < 0.001 | 1.864 | (1.59-4.387) |

| Morphology as Paris classification 0-IIa | 0.927 | 0.048 | 2.528 | (2.21-5.501) |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 0.513 | < 0.001 | 1.671 | (1.41-4.048) |

| Pyloric adenoma: | ||||

| BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2 | 0.442 | < 0.001 | 1.560 | (1.26-6.152) |

| Largest polyp size ≥ 30 mm | 0.712 | < 0.001 | 2.039 | (1.34-5.11) |

| Multiple polyps | 0.870 | < 0.001 | 2.386 | (2.08-5.268) |

| Morphology as Paris classification 0-Ip | 0.863 | 0.001 | 2.370 | (2.06-5.242) |

| Independent predictors for recurrence after endoscopic resection | ||||

| Family history of gastric adenocarcinoma | 0.287 | < 0.001 | 1.332 | (1.1-3.431) |

| Largest polyp size ≥ 30 mm | 0.714 | < 0.001 | 2.042 | (1.76-4.692) |

| Number of polyps > 3 | 0.411 | < 0.001 | 1.509 | (1.26-3.757) |

| Lesser curvature as location | 0.542 | < 0.001 | 1.720 | (1.46-4.135) |

| Morphology as Paris classification 0-IIc | 0.127 | < 0.001 | 1.135 | (1.092-3.055) |

| Active Helicobacter pylori infection | 0.139 | < 0.001 | 1.149 | (1.019-3.083) |

Foveolar adenoma: BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2 (OR 1.111; 95%CI: 1.030-3.656), history of NSAID intake (OR 1.864; 95%CI: 1.590-4.387), largest polyp size ≥ 30 mm (OR 1.560; 95%CI: 1.060-4.160), Paris classification 0-IIa (OR 2.528; 95%CI: 2.210-5.501) and underlying intestinal metaplasia (OR 1.671; 95%CI: 1.410-4.048) were all potential risk factors associated with foveolar adenoma (Table 5; Figure 2D-F).

Pyloric adenoma: BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2 (OR 1.560; 95%CI: 1.260-6.152), largest polyp size ≥ 30 mm (OR 2.039; 95%CI: 1.340-5.110), multiple polyps (OR 2.386; 95%CI: 2.08-5.268) and Paris classification 0-Ip (OR 2.370; 95%CI: 2.060-5.242) were all potential risk factors associated with pyloric adenoma (Table 5; Figure 2G-I).

The only patient with oxyntic adenoma was an 80-year-old female patient with a history of cardiovascular morbidity and a BMI of 25 kg/m2. She had a history of PPI, statin, and NSAID use and no personal or family history of cancer. She complained of epigastric pain, and endoscopy revealed 10 polyps at the greater curvature; the largest polyp diameter was 25 mm. The polyps were completely removed via EMR, revealing oxyntic adenoma with LGD with normal underlying gastric mucosa and no active H. pylori infection. A 3-month follow-up endoscopy revealed a residual LGD adenoma resected via EMR.

A higher post-ER recurrence rate was observed in the foveolar group (20% at 1 year, 28% at 2 years) than in the intestinal group (5.9% at 1 year, 14% at 2 years) and the pyloric group (0% at 1 year, 20% at 2 years); however, the difference was not statistically significant (log rank P = 0.19) (Figure 3).

Multivariate Cox regression analysis of the independent predictors for adenoma recurrence after ER revealed that a family history of gastric adenocarcinoma (HR = 1.332; 95%CI: 1.10-3.431, P < 0.001) and active H. pylori infection (HR = 1.149; 95%CI: 1.019-3.083, P < 0.001) were independent predictors of recurrence after ER in different gastric adenomas. Among the baseline endoscopic characteristics, a largest polyp size 30 mm (HR = 2.042; 95%CI: 1.760-4.692, P < 0.001), more than 3 polyps (HR = 1.509; 95%CI: 1.260-3.757, P < 0.001), a lesser curvature as the lesion location (HR = 1.720, 95%CI: 1.460-4.135, P < 0.001) and a Paris classification of 0-IIc (HR = 1.135, 95%CI: 1.092-3.055, P < 0.001) were in

Understanding the distinct features of gastric adenoma subtypes is crucial for appropriate management. A retrospective analysis of 79 endoscopically resected lesions was performed and revealed that 38% of the adenomas were of the non-intestinal type. Intestinal adenomas were more likely to occur in older patients (≥ 65) with a history of gastric adenocarcinoma and atrophic gastritis. Foveolar adenomas, on the other hand, displayed associations with NSAID exposure,

Gastric adenoma subtypes display heterogeneity, with intestinal types being the most prevalent. Interpretation of data concerning less common subtypes should consider this context. This study includes a limited number of non-intestinal adenomas, specifically six pyloric adenomas and one oxyntic adenoma, which constrains comprehensive subtype comparisons and may influence the applicability of results to these rarer subtypes.

Prior studies report gastric adenoma recurrence rates after ER ranging from 3%-20.9%[11,18]. In our study, with a 26.3 ± 21.8-month follow-up, residual adenoma occurred in 5.1% and recurrence in 12.7% of patients. Foveolar and pyloric adenomas showed higher recurrence rates than intestinal adenomas (17.4%, 16.7%, and 8.1%, respectively, P = 0.070), although mean recurrence times were similar (P = 0.833). Consistent with previous findings, advanced histology did not predict post-ER recurrence in patients with gastric adenomas[11,19].

A significant 43.5% of foveolar adenomas in our study were found in conjunction with early gastric adenocarcinoma, highlighting their potential for malignant transformation. This observation reinforces existing research that advocates for complete en bloc resection and meticulous follow-up to accurately distinguish foveolar adenomas from hyperplasia and manage their inherent risk[19-21].

The increased recurrence tendency of pyloric adenomas necessitates vigilant follow-up. While infrequent, these lesions are clinically significant due to their malignant potential and the substantial association with adenocarcinoma, reported between 12% and 30% in large-scale studies[22,23].

The present investigation identified a family history of gastric adenocarcinoma, active H. pylori infection, polyp

Furthermore, studies consistently indicate that larger early gastric adenocarcinoma (> 2 cm) are more prone to recurrence[2,11,24]. Despite some variability in published research[25], our study identified active H. pylori infection as an independent predictor of post-ER recurrence. This observation is consistent with other study demonstrating the beneficial impact of H. pylori eradication in mitigating metachronous neoplastic recurrence[26].

The findings of our study have direct clinical implications for patient management and surveillance strategies with some concluded recommendations: (1) Implement risk-stratified surveillance intervals with 3-months follow up endoscopy: Patients with high-risk features (family history, large polyps ≥ 30 mm, > 3 polyps, or Paris 0-IIc morphology), while those without these risk factors could potentially be surveilled at 6-month intervals; (2) Prioritize H. pylori testing and eradication in all gastric adenoma patients to address this modifiable risk factor; (3) Consider more aggressive endoscopic approaches for pyloric adenomas, given that they are associated with larger size and multiplicity; and (4) Maintain heightened surveillance for foveolar adenomas due to their higher recurrence rates and association with early gastric adenocarcinoma.

To our knowledge, this is the first Western study to provide a detailed characterization of gastric adenoma subtypes, bridging a significant gap in literature. The prospective, single-center design, coupled with long-term follow-up and expert pathological review of all ER cases, including hyperplastic lesions, lends credibility to our findings. However, limitations such as the small sample size of non-intestinal adenomas and heterogeneous resection techniques necessitate further validation through larger, multi-center studies. Future research should focus on elucidating the underlying mechanisms driving subtype-specific development and recurrence, particularly for oxyntic adenomas.

This study identifies distinct risk factor profiles for different subtypes of gastric adenomas, suggesting that intestinal, foveolar, and pyloric adenomas may have different underlying pathogenic mechanisms. Intestinal adenomas were significantly associated with age ≥ 65 years, statin use, family history of gastric adenocarcinoma, atrophic gastritis, and antral location, while foveolar adenomas were linked to higher BMI, NSAID use, and intestinal metaplasia. Pyloric adenomas were more likely to present as large or multiple polyps, particularly in patients with higher BMI. Furthermore, several independent predictors of recurrence after ER were identified, including family history of gastric neoplasia, largest polyp size ≥ 30 mm, presence of more than three polyps, lesion location on the lesser curvature, Paris 0-IIc morphology, and active H. pylori infection. These findings underscore the importance of subtype-specific risk assessment and tailored surveillance strategies to improve clinical outcomes and reduce recurrence rates in patients undergoing ER for gastric adenomas.

| 1. | Fujiwara Y, Arakawa T, Fukuda T, Kimura S, Uchida T, Obata A, Higuchi K, Wakasa K, Sakurai M, Kobayashi K. Diagnosis of borderline adenomas of the stomach by endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy. 1996;28:425-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Noh CK, Lee E, Lee GH, Lim SG, Lee KM, Roh J, Kim YB, Park B, Shin SJ. Risk factor-based optimal endoscopic surveillance intervals after endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric adenoma. Sci Rep. 2021;11:21408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yacoub H, Bibani N, Sabbah M, Bellil N, Ouakaa A, Trad D, Gargouri D. Gastric polyps: a 10-year analysis of 18,496 upper endoscopies. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Shibagaki K, Ishimura N, Kotani S, Fukuyama C, Takahashi Y, Kishimoto K, Yazaki T, Kataoka M, Omachi T, Kinoshita Y, Hasegawa N, Oka A, Mishima Y, Mishiro T, Oshima N, Kawashima K, Nagase M, Araki A, Kadota K, Ishihara S. Endoscopic differential diagnosis between foveolar-type gastric adenoma and gastric hyperplastic polyps in Helicobacter pylori-naïve patients. Gastric Cancer. 2023;26:1002-1011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Abraham SC, Montgomery EA, Singh VK, Yardley JH, Wu TT. Gastric adenomas: intestinal-type and gastric-type adenomas differ in the risk of adenocarcinoma and presence of background mucosal pathology. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1276-1285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Vieth M, Kushima R, Mukaisho K, Sakai R, Kasami T, Hattori T. Immunohistochemical analysis of pyloric gland adenomas using a series of Mucin 2, Mucin 5AC, Mucin 6, CD10, Ki67 and p53. Virchows Arch. 2010;457:529-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sakurai U, Lauwers GY, Vieth M, Sawabe M, Arai T, Yoshida T, Aida J, Takubo K. Gastric high-grade dysplasia can be associated with submucosal invasion: evaluation of its prevalence in a series of 121 endoscopically resected specimens. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:1545-1550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kim YJ, Park JC, Kim JH, Shin SK, Lee SK, Lee YC, Chung JB. Histologic diagnosis based on forceps biopsy is not adequate for determining endoscopic treatment of gastric adenomatous lesions. Endoscopy. 2010;42:620-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Noh CK, Jung MW, Shin SJ, Ahn JY, Cho HJ, Yang MJ, Kim SS, Lim SG, Lee D, Kim YB, Cheong JY, Lee KM, Yoo BM, Lee KJ. Analysis of endoscopic features for histologic discrepancies between biopsy and endoscopic submucosal dissection in gastric neoplasms: 10-year results. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51:79-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Farinati F, Rugge M, Di Mario F, Valiante F, Baffa R. Early and advanced gastric cancer in the follow-up of moderate and severe gastric dysplasia patients. A prospective study. I.G.G.E.D.--Interdisciplinary Group on Gastric Epithelial Dysplasia. Endoscopy. 1993;25:261-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Park TY, Jeong SJ, Kim TH, Lee J, Park J, Kim TO, Park YE. Long-term outcomes of patients with gastric adenoma in Korea: A retrospective observational study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e19553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pimentel-Nunes P, Libânio D, Marcos-Pinto R, Areia M, Leja M, Esposito G, Garrido M, Kikuste I, Megraud F, Matysiak-Budnik T, Annibale B, Dumonceau JM, Barros R, Fléjou JF, Carneiro F, van Hooft JE, Kuipers EJ, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Management of epithelial precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS II): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group (EHMSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED) guideline update 2019. Endoscopy. 2019;51:365-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 712] [Cited by in RCA: 716] [Article Influence: 102.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2018 (5th edition). Gastric Cancer. 2021;24:1-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 735] [Cited by in RCA: 1415] [Article Influence: 283.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Pimentel-Nunes P, Libânio D, Bastiaansen BAJ, Bhandari P, Bisschops R, Bourke MJ, Esposito G, Lemmers A, Maselli R, Messmann H, Pech O, Pioche M, Vieth M, Weusten BLAM, van Hooft JE, Deprez PH, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial gastrointestinal lesions: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2022. Endoscopy. 2022;54:591-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 579] [Cited by in RCA: 479] [Article Influence: 119.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ezoe Y, Muto M, Uedo N, Doyama H, Yao K, Oda I, Kaneko K, Kawahara Y, Yokoi C, Sugiura Y, Ishikawa H, Takeuchi Y, Kaneko Y, Saito Y. Magnifying narrowband imaging is more accurate than conventional white-light imaging in diagnosis of gastric mucosal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:2017-2025.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Maki S, Yao K, Nagahama T, Beppu T, Hisabe T, Takaki Y, Hirai F, Matsui T, Tanabe H, Iwashita A. Magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging is useful in the differential diagnosis between low-grade adenoma and early cancer of superficial elevated gastric lesions. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:140-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Nonaka T, Inamori M, Honda Y, Kanoshima K, Inoh Y, Matsuura M, Uchiyama S, Sakai E, Higurashi T, Ohkubo H, Iida H, Endo H, Fujita K, Kusakabe A, Atsukawa K, Takahashi H, Tateishi Y, Maeda S, Ohashi K, Nakajima A. Can magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging discriminate between carcinomas and low grade adenomas in gastric superficial elevated lesions? Endosc Int Open. 2016;4:E1203-E1210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chung GE, Chung SJ, Yang JI, Jin EH, Park MJ, Kim SG, Kim JS. Development of Metachronous Tumors after Endoscopic Resection for Gastric Neoplasm according to the Baseline Tumor Grade at a Health Checkup Center. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2017;70:223-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shibagaki K, Fukuyama C, Mikami H, Izumi D, Yamashita N, Mishiro T, Oshima N, Ishimura N, Sato S, Ishihara S, Nagase M, Araki A, Ishikawa N, Maruyama R, Kushima R, Kinoshita Y. Gastric foveolar-type adenomas endoscopically showing a raspberry-like appearance in the Helicobacter pylori -uninfected stomach. Endosc Int Open. 2019;7:E784-E791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Leone PJ, Mankaney G, Sarvapelli S, Abushamma S, Lopez R, Cruise M, LaGuardia L, O'Malley M, Church JM, Kalady MF, Burke CA. Endoscopic and histologic features associated with gastric cancer in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:961-968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bhandari P, Abdelrahim M, Alkandari AA, Galtieri PA, Spadaccini M, Groth S, Pilonis ND, Subhramaniam S, Kandiah K, Hossain E, Arndtz S, Bassett P, Siggens K, Htet H, Maselli R, Kaminski MF, Seewald S, Repici A. Predictors of long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric neoplasia in the West: a multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2023;55:898-906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Vieth M, Kushima R, Borchard F, Stolte M. Pyloric gland adenoma: a clinico-pathological analysis of 90 cases. Virchows Arch. 2003;442:317-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chen ZM, Scudiere JR, Abraham SC, Montgomery E. Pyloric gland adenoma: an entity distinct from gastric foveolar type adenoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:186-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nam HS, Choi CW, Kim SJ, Kang DH, Kim HW, Park SB, Ryu DG. Endoscopic predictive factors associated with local recurrence after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:1000-1007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Noh CK, Lee E, Park B, Lim SG, Shin SJ, Lee KM, Lee GH. Effect of Helicobacter pylori Eradication Treatment on Metachronous Gastric Neoplasm Prevention Following Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Gastric Adenoma. J Clin Med. 2023;12:1512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Choi JM, Kim SG, Choi J, Park JY, Oh S, Yang HJ, Lim JH, Im JP, Kim JS, Jung HC. Effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication for metachronous gastric cancer prevention: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;88:475-485.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/