Published online Nov 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i11.110030

Revised: July 6, 2025

Accepted: October 23, 2025

Published online: November 16, 2025

Processing time: 170 Days and 16.2 Hours

Gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) is a critical complication often seen in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), especially those undergoing dual antiplatelet therapy. GIB is associated with increased mortality and prolonged hospitalization, particularly in ACS patients. Despite advancements in management strategies, the role of gastrointestinal endoscopy (GIE) in this population remains controversial, with concerns about timing, safety, and clinical outcomes.

To evaluate the safety and efficacy of GIE in patients with ACS and acute GIB, focusing on outcomes such as mortality, hospital length of stay (LOS), hemorrhage control, rebleeding, and blood transfusion requirements.

Following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines, a systematic review was conducted using databases including PubMed, Cochrane, and EMBASE, up to December 2024. The protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42025630188). Study quality was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 tool for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cohort studies.

Four studies met the inclusion criteria, comprising one RCT and three cohort studies with a total population of 1676130 patients. Most studies indicated that GIE was associated with improved survival in ACS patients with GIB. Three of our studies reported lower mortality rates in patients undergoing GIE compared to those managed without endoscopy, although this varied by study. While GIE demonstrated effectiveness in controlling hem

GIE has the potential to improve survival in certain patients with ACS complicated by GIB; however, determining the ideal timing and appropriate candidates necessitates careful individual assessment. While evidence suggests benefits, the limitations of observational studies warrant caution. Collaboration between cardiology and gastroenterology is essential to optimizing outcomes. Future randomized trials should focus on timing, severity, and diverse populations to refine guidelines and improve care for this high-risk group.

Core Tip: In patients with acute coronary syndrome and gastrointestinal bleeding, gastrointestinal endoscopy reduces in-hospital mortality, enhances hemostasis, and lowers 3-day rebleeding rates. Its effects on hospital length of stay and blood transfusion requirements are variable, although early gastrointestinal endoscopy may decrease overall costs through reduced transfusions. Existing data are mainly observational and heterogeneous, with potential dataset overlap. Rigorous randomized controlled trials are needed to determine optimal timing, patient selection, and integrated cardiology–gastroenterology management strategies for this high-risk population.

- Citation: Calderon-Martinez E, Abreu Lopez B, Flores Monar G, Dave R, Teran Hooper C, Salolin Vargas VP, Shah YR, Patel R, Dahiya DS, Gangwani MK, Advani R. Effectiveness of endoscopy in patients with concomitant gastrointestinal bleeding and acute coronary syndrome: A systematic review. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(11): 110030

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i11/110030.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i11.110030

Gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) is categorized based on its anatomic source. Upper GIB (UGIB) occurs above the ligament of Treitz and involves the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum[1]. Lower GIB (LGIB) originates from the colon, rectum, or anus. Middle GIB (MGIB) refers to bleeding between the ligament of Treitz and the ileocecal valve[2,3]. GIB accounts for an average of 1.5 million ambulatory visits per year in the United States. UGIB has a higher mortality rate and is a more frequent cause of emergency room visits, leading to over 786470 hospitalizations annually in the United States, followed by acute LGIB, accounting for more than 211350 admissions each year[4,5]. Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) encompasses three clinically distinct entities: ST-elevation myocardial infarction, non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and unstable angina[6,7]. In recent years, the incidence of NSTEMI has risen, now accounting for approximately 60%-70% of ACS presentations[5,6]. Management of ACS involves multiple modalities, including revascularization through cardiac catheterization and dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT)[7]. However, DAPT significantly increases the risk of GIB[3,8-10]. Patients with ACS who experience GIB have a 30-day mortality rate of 9.6%, significantly higher than the 1.4% observed in ACS patients without GIB[3]. Despite advancements in diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, the management of GIB in ACS patients remains challenging. Healthcare professionals frequently face a dilemma due to inconsistent guidelines concerning the appropriate timing, modality, and safety of the gastrointestinal endoscopy (GIE) in this population, raising concerns for potential complications[11]. Research on the safety of GIE in patients with ACS and GIB has been limited, often focusing primarily on UGIB and esophagogastroduodenoscopy. The aim of this study was to investigate clinical outcomes in patients simultaneously presenting with acute GIB and ACS. Primary outcomes were mortality and hospital length of stay. Secondary outcomes included bleeding control, rebleeding, transfusion requirements, sex and gender, and cost analysis.

The present meta-analysis followed the recommendations and criteria established by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines. The protocol was pre-registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Review with the identifier code: No. CRD42025630188.

By researching PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, Scopus, CNKI, EMBASE, and CINAHL on December 22, 2024. The search strategy included a combination of MeSH terms and keywords such as “gastrointestinal bleeding”, “acute coronary syndrome”, “endoscopy”, “mortality”, “rebleeding”, and “dual antiplatelet therapy”. Boolean operators (AND, OR) and truncation (*) were employed to optimize search precision. Specific search strategies for each database are detailed in Supplementary Tables 1-8.

Types of study: Relevant studies published from the database’s inception to 2024 that were available in English were systematically reviewed. They were meticulously screened and analyzed in randomized clinical trials, cohort studies, and case-control studies. Case series were excluded: Cross-sectional studies, dissertations, book chapters, protocol articles, reviews, news articles, conference abstracts, letters to the editor, editorials, and commentaries. Additionally, studies that lacked a clear description of their operationalization were duplicated when necessary, data were unavailable, or no response was received from the original authors.

Types of participants: In this study, participants of all ages and sexes diagnosed with GIB and ACS were included. GIB was defined as bleeding within the gastrointestinal tract. Both upper and LGIB cases were eligible; UGIB was defined as bleeding proximal to the ligament of Treitz, and LGIB was defined as bleeding distal to the ligament of Treitz. The severity of GIB was assessed according to criteria that varied across the included studies; however, clinically significant or severe GIB was generally characterized by the need for blood transfusions, hemorrhage control failure, rebleeding within three days, or an increased risk of mortality as reported in the included studies. Confirmation of GIB was based on clinical or endoscopic findings. ACS was categorized as either STEMI or NSTEMI. STEMI was identified by persistent ST-segment elevation in two contiguous leads (meeting standard thresholds) or new left bundle branch block, accompanied by ischemic symptoms and elevated troponins. NSTEMI was defined by elevated troponin levels exceeding the 99th percentile, ischemic symptoms, and electrocardiogram changes without persistent ST-segment elevation or unstable angina. Participants were excluded if their GIB originated from non-gastrointestinal sources (e.g., pulmonary or vascular etiologies), if ACS was secondary to another underlying condition, or if diagnostic data for GIB or ACS were insufficient or inconclusive.

Types of intervention: This study will evaluate the effect of gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures in patients with concomitant GIB and ACS. Specifically, we will compare outcomes in patients who underwent either upper GIE or lower GIE (colonoscopy) during their hospital stay with those who did not receive any endoscopic intervention.

This study evaluated several key outcomes. The primary outcomes were all-cause mortality and hospital length of stay. Secondary outcomes included healthcare costs and blood transfusion requirements. Studies that did not report data on these specified primary and secondary outcomes were excluded from the analysis.

Following an initial screening based on the title and abstract, two reviewers (Dave R and Gangwani MK) independently selected trials for inclusion in this review using predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. This selection was performed using Rayyan[1], and consultation with a third reviewer (Calderon-Martinez E) resolved disagreements about including the studies. Subsequently, a full-text analysis was conducted with two reviewers (Lopez BA, Salolin Vargas VP) independently selecting trials to include in the review using predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Consensus and consultation with a third review author (Calderon-Martinez E) resolved disagreements about including studies.

Data extraction was conducted in December 2024. Two independent reviewers extracted data from each included study using a standardized data extraction form. The following information was extracted: Author(s), year of publication, country of publication, study design, sample size (number of cases and controls), participant characteristics (e.g., age, sex, comorbidities), intervention or exposure, comparison group, and outcome measures of interest.

Two independent reviewers evaluated the risk of bias in each study, using the Risk of Bias 2.0 tool by Cochrane[2] and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale[3] for case-control and cohort studies to assess the risk of bias. Any reviewer discrepancies have been resolved through discussion with a third, blinded reviewer.

A meta-analysis will be performed if 3 or more studies report the same variable using R version 3.4.3[4]. The pooled effect of the outcomes will be a relative risk or a standardized mean difference and 95% confidence interval. The I2 statistic assessed heterogeneity, and the following cut-off values were used for interpretation: < 25, 25-50, and > 50 will be considered small, medium, and large heterogeneity, respectively. We also planned outlier and influence diagnostics following Viechtbauer and Cheung[5]. Egger’s regression test will examine publication bias when ten or more reports with the same outcome are available[6]. Whenever possible, subgroup analyses will be performed for primary outcomes.

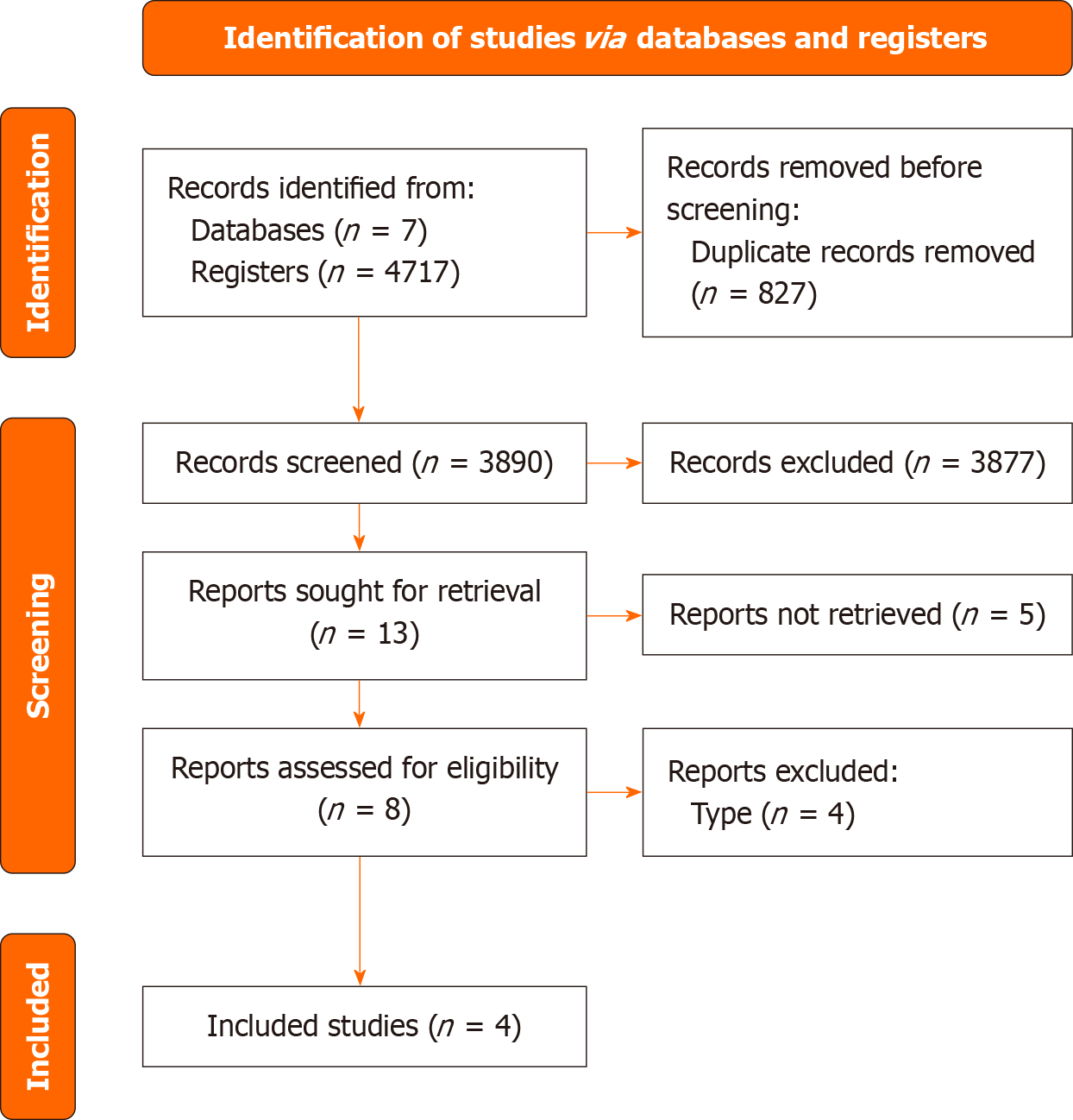

In the literature search, a total of 4717 citations were screened. A total of 13 articles were identified after reviewing the titles and abstracts. After the full-text review, 4 studies met the inclusion criteria. Therefore, 1 randomized controlled trial (RCT) and 3 cohort studies were included in our research. This process is summarized in our PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1).

General characteristics: Our systematic review analyzed outcomes from four studies involving patients with concurrent ACS and GIB, including one RCT and three cohort studies, with a total of 1676130 patients. Of these, 245443 (14.64%) were in the intervention group, while 1430687 (85.35%) formed the control group. Three studies (75%) were conducted in the United States, and 25% from Taiwan. All studies reported a higher proportion of male participants compared to female participants in both the intervention and control groups. Notably, Chung et al[7] had the smallest sample size among the studies. Both Elkafrawy et al[8] and Chung et al[7] observed that male participants outnumbered females by over 20% in both groups. The studies by Hoffman et al[9], Modi et al[10], and Elkafrawy et al[8] all used the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database to examine outcomes in patients with ACS and GIB, but each had a different focus. Hoffman et al[9] looked specifically at 2016 data to study mortality rates for patients undergoing GIE or colonoscopy. Modi et al[10] analyzed data from 2007 to 2013, focusing on outcomes of endoscopic procedures in patients with GIB after a myocardial infarction. Elkafrawy et al[8] took a broader approach, reviewing outcomes from 2005 to 2014 for various types of endoscopies in ACS patients with GIB. Endoscopy encompasses a range of procedures used to diagnose patients with gastrointestinal diseases, and each study employed a different procedural intervention. Elkafrawy et al[8] included procedures such as GIE, small intestinal endoscopy, colonoscopy, or flexible sigmoidoscopy as interventions for their study. Hoffman et al[9] and Chung et al[7] identified GIE as the primary intervention for their respective intervention groups. Modi et al[10] utilized GIE or colonoscopy, as the intervention for their intervention group. The study by Hoffman et al[9] conclude that GIE is generally safe for hospitalized AMI patients when clinically necessary, without specifying differences between men and women. Chung et al[7] explore the benefits of early endoscopy in ACS patients with UGIB, emphasizing its utility but not linking recommendations to gender. Similarly, Modi et al[10] evaluated the safety of colonoscopy for post-myocardial infarction GIB and confirmed its viability in this context without addressing gender distinctions. While these studies focus on clinical safety and procedural timing, other research highlights gender-based differences in endoscopic findings and patient preferences. However, endoscopy guidelines are predominantly driven by symptoms, risk factors, and clinical indications rather than gender. A meta-analysis was not performed for any variable due to overlapping of population and low number of studies. A meta-analysis for none of the variables was performed due to the number of included articles and double counting concerns (Table 1).

| Ref. | Elkafrawy et al[8], 2021 | Hoffman et al[9], 2020 | Chung et al[7], 2022 | Modi et al[10], 2017 |

| Country | United States | United States | Taiwan | United States |

| Study design | Cohort | Cohort | RCT | Cohort |

| Number of patients included (total) | 269483 | 1281749 | 43 | 124855 |

| Number of patients intervention group | 183248 | 53035 | 22 | 9138 |

| Number of patients control group | 86235 | 1228714 | 21 | 115717 |

| Mean ± SD age (endoscopy group) | 72.32 ± 11.72 | 71.1 | 63.55 ± 12.19 | Colonoscopy: 70.78 ± 24.5; EGD: 69.56 ± 25.3 |

| Mean ± SD age (non-endoscopy group) | 71.27 ± 12.29 | 68.9 | 70.67 ± 12.82 | 67.13 ± 33.8 |

| Gender distribution (endoscopy group) | F = 63369 (34.6); M = 120040 (65.4) | F: 23610; M: 29425 | F: 4; M: 18 | F = 43.13; M = 56.87 |

| Gender distribution (non-endoscopy group) | F = 28003 (32.5); M = 58070 (67.5) | F: 523345; M: 704785 | F: 8; M: 13 | F = 38.7; M = 61.3 |

| Severity of GIB | Higher transfusion requirement (55.9% vs 50.5%) | Severity inferred via mortality outcomes | Improved hemorrhage control (4.55% vs 23.81%), significantly lower 3-day rebleeding rate (4.55% vs 28.57%) | Severity inferred via mortality outcomes |

| Type of endoscopy | EGD, small intestinal endoscopy, colonoscopy, or flexible sigmoidoscopy | Esophagogastroduodenoscopies (EGDs) | EGD | Colonoscopy, with or without EGD |

| Type of ACS | Acute myocardial infarction, subendocardial infarction, and acute coronary occlusion without infarction | Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI): 58.9; demand ischemia (NSTEMI type II): 32.5; ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI): 8.7 | Unstable angina, STEMI, NSTEMI | Acute coronary syndrome STEMI |

| Mortality cases | 7027 (3.8) | 9.9 (95%CI: 9.3-10.5) | 1 | 33 |

| Mortality control | 7421 (8.6) | Lower: 0.80, P < 0.001 | 0 | 6941 (no endoscopy group), 384 (EGD only) |

| Hospital stay cases mean ± SD | 6.59 ± 7.81 | 11.8 days (95%CI: 11.5-12.2) | ITT: 13.64 ± 10.99, PP: 13.14 ± 11.01 | 12.53 days (CI: 11.43-13.63) |

| Hospital stay controls mean ± SD | 7.84 ± 9.73 | 5.6 days (95%CI: 5.5-5.6) | ITT: 11.57 ± 5.67; PP: 11.05 ± 5.66 | 10.44 days (CI: 10.30-10.58) |

| Blood transfusion requirement (endoscopy group) mean ± SD | 102484 (55.9) | N/A | ITT: 0.77 ± 1.23, PP: 0.62 ± 1.02 | N/A |

| Blood transfusion requirement (non-endoscopy group) mean ± SD | 43455 (50.5) | N/A | ITT: 2.76 ± 2.86, PP: 2.63 ± 2.99 | N/A |

| Key points | Patients who underwent endoscopy had a lower mortality, hospital length, and mechanical ventilation rate compared to the control group | Endoscopy reduced adjusted mortality despite sicker patients | EE had a higher rate of hemorrhage control, lower 3-day rebleeding rate | Patients undergoing endoscopy showed a lower mortality rate |

Hospital length stay: Among the studies analyzed, Elkafrawy et al[8] highlighted that GIE was independently associated with a shorter hospital LOS, while identifying factors such as congestive heart failure, shock, and mechanical ventilation as contributors to prolonged LOS. However, both Chung et al[7] and Modi et al[10] reported no statistical significant differences in hospitalization LOS between patients who underwent GIE and those who did not. Hoffman et al[9], on the other hand, did not directly compared LOS between these groups, despite showing a shorter LOS in controls. Overall, 50% of the studies reported no significant difference in LOS, 25% identified a shorter LOS with GIE, and 25% did not provide a direct comparison.

Mortality: Among the four studies analyzed, three (75%)-Hoffman et al[9], Elkafrawy et al[8], and Modi et al[10]-demonstrated that GIE was associated with reduced mortality. Hoffman et al[9] found that among patients with ACS, those undergoing gastrointestinal procedures, such as GIE or colonoscopy, had lower in-hospital mortality, after adjusting for age, Elixhauser index, need for angiogram, sex and race. Specifically, mortality was 7.5% when GIE was performed before catheterization and 6.7% when catheterization was performed before GIE, compared to 3.4% for patients undergoing catheterization alone. However, after adjusting for patient factors, undergoing GI procedures was associated with lower in-hospital mortality, with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.80. The timing of GIE also influenced outcomes, with early GIE (within 3 days of admission) being associated with higher mortality compared to delayed GIE (performed ≥ 4 days after admission).

Similarly, Modi et al[10] reported that patients undergoing GIE overall had a lower mortality rate (3.8%) compared to those who did not undergo GIE (8.6%; P < 0.001). Additionally, Modi et al[10] noted that GIE alone was associated with higher mortality rates compared to colonoscopy. Elkafrawy et al[8] also found that patients who underwent GIE during hospitalization had significantly lower mortality rates (3.8%) compared to those who did not receive the procedure (8.6%). Both Elkafrawy et al[8] and Modi et al[10] identified factors such as coagulopathy, shock, and mechanical ventilation as being linked to increased mortality. In contrast, one study (25%)-Chung et al[7]-reported no significant differences in mortality between patients undergoing GIE and those who did not. However, one patient in the GIE group died within 24 hours due to multiorgan failure secondary to poor cardiac function (P = 0.335).

Hemorrhage control and rebleeding rate: Hemorrhage control and rebleeding rates were assessed in only one study. Chung et al[7] reported that GIE significantly reduced the failure rate of hemorrhage control (4.55% vs 23.81%) and the 3-day rebleeding rate (4.55% vs 28.57%, P = 0.033) compared to no GIE. The remaining three studies (75%) did not evaluate these outcomes.

Blood transfusion requirements: Blood transfusion requirements were assessed in only one study. Elkafrawy et al[8] find that patients undergoing GIE were more likely to require blood transfusions (55.9%) compared to those who did not undergo GIE (50.5%).

Sex and gender analysis: Gender-related differences were identified in half of the included studies. Chung et al[7] found that male patients had a higher risk of minor and major complications (odds ratios of 3.50 and 4.25, respectively) after GIE, indicating a need for gender-sensitive management strategies, while Elkafrawy et al[8] observed that women were a factor in increasing the LOS. Modi et al[10] identified the female population to be associated with an increase in in-hospital mortality despite the intervention, while Hoffman et al[9] did not find female sex to be associated with in-hospital mortality.

Cost analysis: Both Modi et al[10] and Chung et al[7] reported that early GIE reduce long-term costs. Modi et al[10] analyzed that performing colonoscopy for GIB in myocardial infarction patients did not significantly increase hospitalization costs. Chung et al[7] found that while early endoscopy procedures might incur upfront costs, they reduced the need for blood transfusions. Early endoscopy procedures were analyzed in 50% of the included studies. Modi et al[10] and Chung et al[7], may initially increase costs but reduce the need for blood transfusions, potentially offsetting these expenses. The remaining 50% of studies did not address the economic impact of early endoscopy procedures. Lee et al’s study[11] demonstrated patients who underwent early endoscopy had significantly shorter hospital stays and lower costs of care compared to those who did not, with both differences reaching strong statistical significance ($2068.00 United States Dollar vs $3662.00 United States Dollar, P = 0.00006). This early intervention helped reduce hospital stay by one day on average.

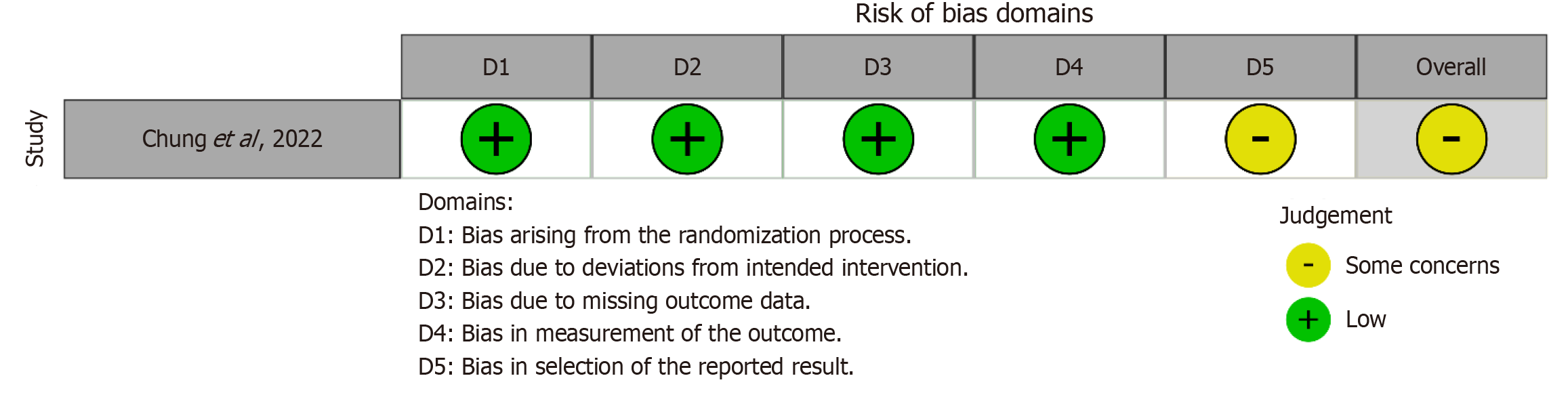

Cochrane’s Risk of Bias 2.0 tool was used to evaluate the quality and potential bias of the single RCT included in our analysis. The results indicated some concerns about bias for this RCT (Figure 2). For the other three studies, which were cohort studies, bias using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale[12] was assessed (Table 2). All three cohort studies were determined to be of good quality with different overall punctuation.

Our study underscores the significant benefits of early endoscopy in patients with ACS and UGIB, particularly in reducing mortality and suggesting potential cost-effectiveness. While previous systematic reviews, such as that by Dorreen et al[13], emphasized the procedural feasibility of endoscopy in this complex population, our analysis provides a more comprehensive evaluation by examining outcomes like blood transfusion requirements, hemorrhage control, and rebleeding rates. These expanded insights offer valuable contributions to understanding endoscopy’s role in this clinical context. However, it is crucial to acknowledge potential limitations, including the likely overlap of patient populations in two studies using the NIS database, which may inflate the pooled estimates of the observed effects. These findings, though promising, highlight the necessity for future research utilizing diverse and independent datasets to further validate the benefits and cost implications of early endoscopic interventions in this high-risk population[13].

Endoscopic intervention in patients with concurrent ACS and GIB appears to significantly reduce LOS. In non-ACS GIB populations, early endoscopy has been shown to shorten LOS by 2-3 days through faster bleeding control and reduced need for additional interventions. Lee et al[11] demonstrated that early endoscopy enabled outpatient care in nearly half of stable GIB patients, lowering hospitalization rates and costs. Similarly, Campbell et al[14] reported improved LOS and cost-effectiveness with timely endoscopy in high-volume centers. These findings are consistent with our observation of reduced LOS in patients undergoing endoscopic intervention for ACS-related GIB. Timely endoscopic management in high-risk populations, such as patients with coagulopathy or those on antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy, has been shown to mitigate complications and accelerate recovery by reducing the need for additional interventions and promoting faster hemostasis[14-16]. These findings align with our observation of reduced LOS in patients with ACS-related GIB, highlighting the importance of early intervention for improved outcomes across patient populations.

Previous studies have reported mixed findings regarding the efficacy of early endoscopy in reducing mortality among ACS patients with GIB[7,11]. Three of the four studies in our analysis demonstrated that endoscopy was associated with reduced mortality after adjusting for confounding factors, suggesting that appropriately performed endoscopy can enhance outcome while another reported no significant difference in mortality[7-10]. These discrepancies likely stem from variations in study design, patient populations, and timing of the intervention. Current guidelines, such as those from the British Society of Gastroenterology, emphasize that the safety and effectiveness of endoscopic procedures in patients on antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy depend on the type of procedure performed and appropriate patient stratification[16]. The American College of Gastroenterology suggests that during GIB and current use of anticoagulants and recommendations of the European Society of GIE, where they recommended that in patients with GIB, a more restrictive transfusion strategy transfusion protocol should be considered, highlighting the importance of propt and individualized correction of anemia and hemostatic abnormalities[17]. Our results shed light on this last statement, that even when blood transfusion requirements can be higher in patients undergoing endoscopy, the importance of individualizing every case with a multidisciplinary approach. This highlights the need for further research to refine the optimal timing and approach to endoscopy in relation to ACS management, balancing the risks and benefits for individual patients[17,18]. Additionally, of patients with ACS and GIB. To draw a robust conclusion, there is a need to stratify the patient more carefully, taking into consideration comorbidities, current treatments, severity of GIB, and type of endoscopy. Need it with better and more detailed stratification and an individualized approach can lead to more personalized and effective management.

Our analysis suggests that endoscopy in ACS patients with UGIB may influence cost-related outcomes, particularly by reducing blood transfusion requirements and associated expenditures. Specifically, our findings indicate that endoscopy may reduce blood transfusion requirements and improve hemorrhage control, consistent with Jawaid et al[15] result in low- and high-risk patients[19]. However, as evidenced by Chung et al[7], who reported greater success in achieving hemostasis and fewer failures in hemorrhage management compared to non-intervention groups[7]. Chung et al[7] highlighted significant cost reductions linked to decreased transfusion needs following early endoscopy, a finding echoed by Lau et al[19], who reported improved outcomes with timely endoscopic intervention, particularly within 24 hours of UGIB onset in patients without ACS[7,16]. Early endoscopy performed shortly after admission in patients without ACS in the emergency department safely triaged 46% of patients with nonvariceal upper GI bleeding to outpatient care, significantly reducing hospital stay and costs, indicating endoscopy utilization significantly reduces healthcare costs[11]. These improvements may translate to reduced costs by minimizing complications, reintervention rates, and prolonged hospital stays.

Elkafrawy et al[8] reported a higher transfusion rate among endoscopy recipients, suggesting variability in outcomes due to differences in patient selection or procedural timing. However, studies in patients without ACS have shown mixed results. However, several studies, including Lee et al[11] and Campbell et al[14], have demonstrated that early endoscopy in UGIB patients without ACS reduces hospitalizations, lowers costs, and improves cost effectiveness, particularly in high-volume centers. In contrast, Jawaid et al[15] observed that while early videocapsule endoscopy reduced diagnostic delays, its cost-effectiveness depended on patient stability and comorbidities. These findings indicate that differences in outcomes between ACS and non-ACS patients are largely influenced by risk stratification and procedural timing. Further research is needed to refine these strategies and clarify their economic impact. However, clinical implementation requires careful patient stratification, multidisciplinary coordination, and adherence to current guidelines on anticoagulation and transfusion strategies. Standardizing protocols for early endoscopy in ACS-related UGIB could enhance outcomes while mitigating risks.

This study faces several limitations. The scarcity of RCTs and reliance on three observational studies introduce methodological heterogeneity. Limited sample sizes and inconsistent reporting of outcomes such as transfusion requirements, hemorrhage control, and rebleeding rates further impede comprehensive evaluation. With only 50% of studies reporting rebleeding rates or transfusion requirements, this creates a major limitation in our research and possibly leads to a potential overstimation of endoscopy benefits, in the same sense another limitation was the lack of an standardized definition of GIB severity, which limit comparability across studies. Additionally, two observational studies may involve overlapping populations due to the use of the NIS database within a shared period. Variability in study designs and patient populations further complicates generalizability. Nonetheless, our analysis indicates a potential mortality benefit of endoscopic interventions; future research should focus on high-quality RCTs to evaluate the effect of early endoscopy on LOS in this specific population. Subgroup analyses should account for variations in healthcare settings and patient characteristics, ensuring generalizability and precision in clinical recommendations. Rigorous validation will help establish endoscopic intervention as a reliable strategy to reduce LOS while maintaining optimal outcomes. As we were not able to perform a meta-analysis, we were therefore unable to conduct a GRADE assessment, which limits the strength of our conclusions.

Our study underscores the critical role of GIE in managing patients with concurrent GIB and ACS. While the evidence suggests potential benefits, the limitations of observational studies call for cautious interpretation. Interdisciplinary collaboration between cardiology and gastroenterology professionals remains vital for optimizing bleeding management and patient outcomes. To enhance clinical practice, future research should focus on RCTs and multi-center studies addressing diverse populations, stratifying by severity, optimal timing of intervention, and key outcomes. These findings serve as a valuable foundation for refining clinical guidelines and improving care for this vulnerable patient group.

| 1. | Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5711] [Cited by in RCA: 14405] [Article Influence: 1440.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng HY, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, Emberson JR, Hernán MA, Hopewell S, Hróbjartsson A, Junqueira DR, Jüni P, Kirkham JJ, Lasserson T, Li T, McAleenan A, Reeves BC, Shepperd S, Shrier I, Stewart LA, Tilling K, White IR, Whiting PF, Higgins JPT. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6581] [Cited by in RCA: 18756] [Article Influence: 2679.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. 2011. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288802810. |

| 4. | R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2024. [cited 1 July 2025]. Available from: https://www.r-project.org/. |

| 5. | Viechtbauer W, Cheung MW. Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1:112-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 912] [Cited by in RCA: 943] [Article Influence: 58.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34245] [Cited by in RCA: 42564] [Article Influence: 1467.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 7. | Chung CS, Chen CC, Chen KC, Fang YJ, Hsu WF, Chen YN, Tseng WC, Lin CK, Lee TH, Wang HP, Wu YW. Randomized controlled trial of early endoscopy for upper gastrointestinal bleeding in acute coronary syndrome patients. Sci Rep. 2022;12:5798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Elkafrawy AA, Ahmed M, Alomari M, Elkaryoni A, Kennedy KF, Clarkston WK, Campbell DR. Safety of gastrointestinal endoscopy in patients with acute coronary syndrome and concomitant gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9:1048-1057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hoffman GR, Stein DJ, Moore MB, Feuerstein JD. Safety of Endoscopy for Hospitalized Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction: A National Analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:376-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Modi RM, Li F, Mumtaz K, Hinton A, Lilly SM, Hussan H, Levine E, Zhang C, Conwell DL, Krishna SG, Stanich PP. Colonoscopy in Patients With Postmyocardial Infarction Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Nationwide Analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;53:23-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lee JG, Turnipseed S, Romano PS, Vigil H, Azari R, Melnikoff N, Hsu R, Kirk D, Sokolove P, Leung JW. Endoscopy-based triage significantly reduces hospitalization rates and costs of treating upper GI bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:755-761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Page MJ, Higgins JPT, Sterne JAC. Assessing risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis: a new tool for systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;10:1091-1096. |

| 13. | Dorreen A, Moosavi S, Martel M, Barkun AN. Safety of Digestive Endoscopy following Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2016:9564529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Campbell HE, Stokes EA, Bargo D, Logan RF, Mora A, Hodge R, Gray A, James MW, Stanley AJ, Everett SM, Bailey AA, Dallal H, Greenaway J, Dyer C, Llewelyn C, Walsh TS, Travis SP, Murphy MF, Jairath V; TRIGGER investigators. Costs and quality of life associated with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: cohort analysis of patients in a cluster randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jawaid S, Marya NB, Hicks M, Marshall C, Bhattacharya K, Cave D. Prospective cost analysis of early video capsule endoscopy versus standard of care in non-hematemesis gastrointestinal bleeding: a non-inferiority study. J Med Econ. 2020;23:10-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Veitch AM, Vanbiervliet G, Gershlick AH, Boustiere C, Baglin TP, Smith LA, Radaelli F, Knight E, Gralnek IM, Hassan C, Dumonceau JM. Endoscopy in patients on antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy, including direct oral anticoagulants: British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guidelines. Gut. 2016;65:374-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Triantafyllou K, Gkolfakis P, Gralnek IM, Oakland K, Manes G, Radaelli F, Awadie H, Camus Duboc M, Christodoulou D, Fedorov E, Guy RJ, Hollenbach M, Ibrahim M, Neeman Z, Regge D, Rodriguez de Santiago E, Tham TC, Thelin-Schmidt P, van Hooft JE. Diagnosis and management of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2021;53:850-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 26.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Abraham NS, Barkun AN, Sauer BG, Douketis J, Laine L, Noseworthy PA, Telford JJ, Leontiadis GI. American College of Gastroenterology-Canadian Association of Gastroenterology Clinical Practice Guideline: Management of Anticoagulants and Antiplatelets During Acute Gastrointestinal Bleeding and the Periendoscopic Period. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117:542-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lau JYW, Yu Y, Tang RSY, Chan HCH, Yip HC, Chan SM, Luk SWY, Wong SH, Lau LHS, Lui RN, Chan TT, Mak JWY, Chan FKL, Sung JJY. Timing of Endoscopy for Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1299-1308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 35.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/