Published online Oct 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i10.112380

Revised: August 5, 2025

Accepted: August 25, 2025

Published online: October 16, 2025

Processing time: 83 Days and 12.2 Hours

Despite growing evidence on endoscopic full thickness resection (EFTR), data on segment-specific outcomes in real-world patients remain limited.

To investigate segment-specific outcomes of EFTR using a full-thickness resection device (FTRD) for neoplastic colorectal lesions.

In this multicenter, retrospective study, EFTR was conducted in unselected real-world patients referred to participating German centers after colonoscopy confirmed EFTR eligibility. The primary outcome was histologically complete resection (R0) of the lesion, including segment-specific outcomes and adverse events (AE). Additional efficacy and safety parameters were investigated by colonic topography for up to 30 days.

The analysis included 102 patients (64 males, 38 females) with a median age of 70 years. EFTR via FTRD was technically successful in all patients. The R0 rate was 81.4%, segment-specifically ranging from 85.0% (rectum), 84.6% (descending colon), 84.0% (ascending colon), 83.3% (cecum), and 76.5% (sigmoid colon) to 73.3% (transverse colon). Examination time was longer in proximal parts compared to the rectosigmoid (non-significant). Overall, 33 patients (32.4%) experienced AE, including only one major complication (0.98%; perforation of sigmoid colon). Abdominal postsurgical pain (18.6%), hematochezia (9.8%), and hemoglobin decline (7.8%) were the most frequent minor complications. Transverse colon lesions had the numerically highest rate of AE, with 8 of 15 patients (53.3%) affected.

EFTR is efficacious for neoplastic colorectal lesions, though R0 rates vary by location. This may impact patient education, selection of the operator, and consideration of laparoscopy surgery.

Core Tip: Endoscopic full thickness resection (EFTR) using full-thickness resection device achieved an overall histologically complete resection (R0) rate of 81.4% with a high technical success rate (99.0%), confirming its applicability in routine clinical settings. R0 resection rates and adverse event (AE) frequencies varied by colonic segment, with the rectum showing the numerically highest efficacy and lowest complication rate, while the transverse colon had the numerically lowest R0 rate and highest AE rate. Postsurgical abdominal pain occurred significantly less often in rectal compared to transverse colon EFTR. These findings suggest that lesion topography plays a relevant role in EFTR outcomes and should be considered in patient counseling, clinical decision-making, and endoscopic training.

- Citation: Albrecht H, Schaefer C, Stegmaier A, Gschossmann J, Hagel A, Raithel M. Real-world topographical efficacy, procedural outcome and safety of endoscopic full thickness resection in colon segments. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(10): 112380

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i10/112380.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i10.112380

Besides cold or hot snare-polypectomy, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), endoscopic full thickness resection (EFTR) is the latest development for endoscopic resections of colorectal neoplasia. This procedure is applied preferentially in recurrent adenomas, lesions showing no lifting sign (failure of a lesion to elevate above surrounding mucosa after submucosal injection), mucosal or submucosal T1/T2-carcinomas, small submucosal tumors or cases requiring additional treatment due to incomplete resection[1-5]. First described by Schurr et al[1] in 2011, the Ovesco Company developed a full-thickness resection device (FTRD) which became European Conformity-marked for colorectal EFTR in 2014[1]. Since then, several studies have investigated the feasibility and safety of this en bloc resection method with positive results[2-6]. A recent systematic review confirmed a substantial overall-likelihood for histologically complete resection (R0) of 82.4% (95%CI: 79.0%-85.5%) and a low overall complication rate (10.2%, 95%CI: 7.8%-12.8%) at the lower gastrointestinal tract (GIT) of prospective studies with selected patients[7].

In clinical practice, the advantage of this method is an improved opportunity for full-thickness, deep transmural endoscopic resection with histological evaluation also of deeper layers (muscularis propria, blood and lymphoid vessels) combined with simultaneous closure of the colon wall defect. This reduces the risk of abdominal contamination and subsequent complications. This method can also be applied effectively for endoscopic treatment of small submucosal tumors, resection of small neuroendocrine tumors (NET) of the rectum or for additional diagnostic purposes, such as diagnosis of chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction[8,9]. However, limitations regarding lesion size applicable for resection (usually smaller than 30 mm) are determined by the amount of tissue that can be grasped in the cap[10]. This size limitation has led to refinement of colonic resection strategies with a combined procedure of EMR and hybrid EFTR within one session[11].

Restricted visibility and flexibility during endoscopic surgery due to the mounted FTRD system may mean a higher colonoscopy level, longer examination times and risk of perforation or tissue injury, which might lead to adverse events (AE) with immediate or delayed complication or post-FTRD bleeding[10]. Although evidence for EFTR using an FTRD is gradually growing, information on colonic section-specific efficacy, outcome parameters and safety is scarce, especially in real-world patients. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the efficacy and safety of EFTR regarding the topographical segments of the large intestine using real-world data of consecutive patients.

A retrospective multicenter data analysis was conducted in patients admitted for EFTR to three referral centers in Germany between November 2014 and December 2020. All patients fulfilling the eligibility criteria were included to avoid bias. EFTR was conducted according to the standard indications using the FTRD System (OVESCO, Tübingen, Germany). For EFTR applicability, patients had to have either a colorectal neoplasia unsuitable for polypectomy, EMR or ESD, or an adenoma involving the appendiceal orifice or a submucosal lesion. All participants required a complete colonoscopy before EFTR and were at least 18 years old. FTR for a histological examination within a colorectal neoplasia was considered as an exclusion criterion. Pregnant patients and those with coagulopathy were not considered for EFTR. Data were obtained from prospectively maintained institutional databases of participating study sites. Before the endoscopic procedure, patients were informed about the examination and the resection procedure. After FTRD, patients received intravenous antibiotics, were kept fasting and monitored for one night at least. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

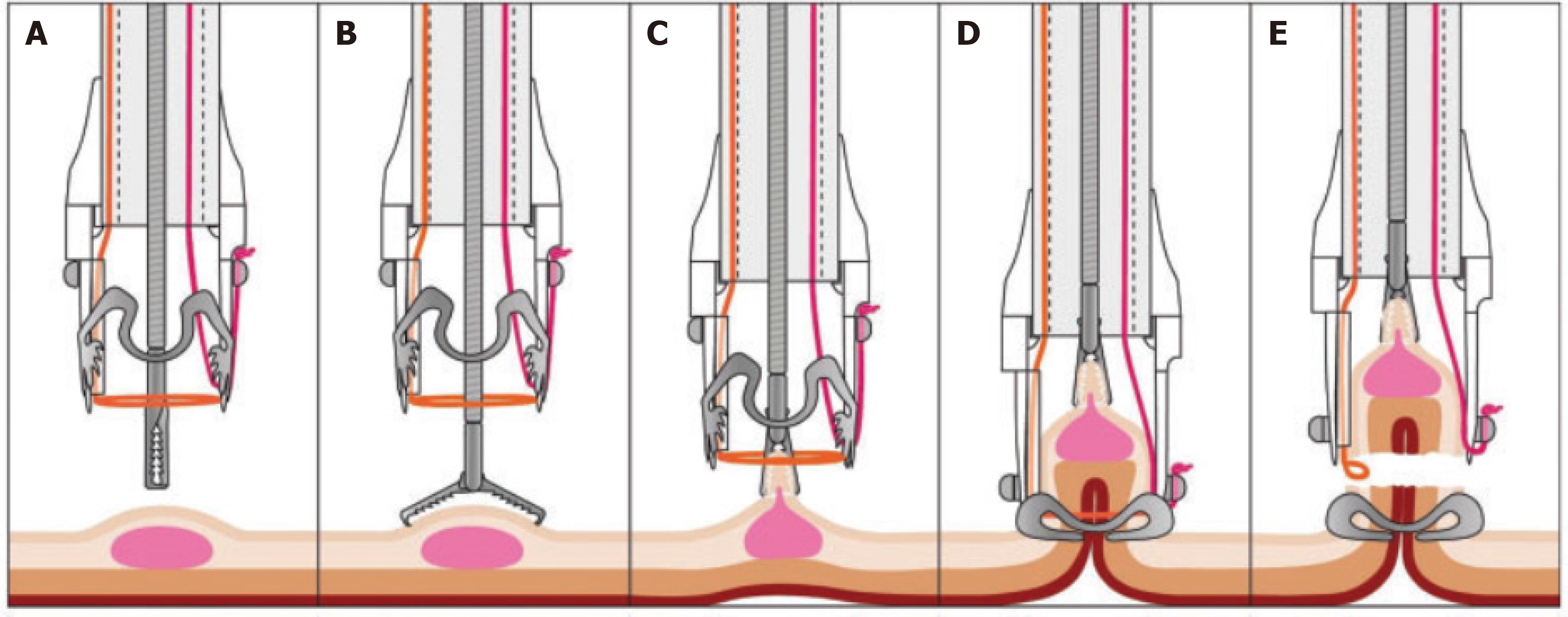

EFTR was performed using an FTRD (Ovesco Endoscopy, Tübingen, Germany), including an over-the-scope-clip (OTSC) system cap following a standardized procedure (Figure 1)[2,9,10]. The cap houses a 14-mm distally integrated monofilament polypectomy snare and has the following dimensions: 13 mm inner diameter and 23 mm length from the endoscope tip. The snare handle is situated on the outer surface of the colonoscope, under a plastic sheath fixed to the instrument. The resection area was marked using coagulation with a probe included in the device. A forceps (FTRD grasper) was used via the operating channel to clasp the lesion and pull it into the cap, followed by immediate OTSC release, resulting in en bloc resection above the clip by the pre-mounted snare. HF-generators used were ERBE Vio 300, ERBE ICC and BOWA HF arc 400 with coagulation current at 20-40 Watt for marking and pure cutting current (200 W) for full-thickness resection[2,9,10].

Demographic data on age and gender were documented, along with lesion characteristics and procedure-related information, including lesion size of the resected specimen, histology, histologically complete and microscopic residual resection rates (R1), duration of the endoscopic procedure, lesion location and AE to EFTR. Complications of particular interest were: Hematochezia, fever, postsurgical abdominal pain, postsurgical hemoglobin decline, any AEs, and severe AE related to EFTR, i.e., events requiring surgical therapy or potentially life-threatening events.

Demographic and histology data as well as overall and site-specific R0 and R1 rates were analysed descriptively. Safety information was analyzed descriptively. If not stated otherwise, descriptive results for interval and ratio data are presented as median (interquartile range). Results for nominal data are given by absolute and relative frequency measures, i.e., n (%) or n/N (%). A generalized linear modelling approach using logistic regression was applied to investigate whether demographic-, procedure-, or lesion-related characteristics are independently related to R0 resection as a measure of efficacy or AE occurrence to EFTR as a measure of safety[12]. The independent variables for R0 resection include an intercept, age, gender, lesion size (length and depth), EFTR procedure duration (minutes) and dummy-coded section of the large intestine with the transverse colon as reference. The independent variables for AE to EFTR include an intercept, age, gender, R0 resection, lesion size (length and depth), EFTR procedure duration (minutes), and dummy-coded section of the large intestine with the transversal colon, again as reference. The transverse colon was chosen as reference in both models as this section showed the lowest R0 rates and the highest number of AE. In both models, lesion size is represented by two dimensions only (i.e., length and depth), as including width would have resulted in compromised findings due to autocorrelation with length. Logistic regression for AE to EFTR could only be conducted to postsurgical abdominal pain due to sample size restrictions. A P value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant for the regression models. R (version 4.2.0) and RStudio (2022.02.3 Build 492) was used as software for statistical analysis[12,13]. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Dr. Matthias Englbrecht from statscoach.

Between November 2014 and December 2020, 105 patients underwent EFTR with an FTRD and were included in the statistical analysis. Three patients admitted to the referral centers for EFTR had to be excluded with their lesions being > 40 mm in diameter, exceeding the dimensions of the FTRD cap. The median age was 70 (64-78) years, with 64 male patients accounting for 62.7% of the patient sample. The median duration of EFTR was 99 (88-115) minutes, whereas the corresponding arithmetic mean (including standard deviation) showed slightly higher values of 104 (32.0) minutes. The overall longest median duration of EFTR was recorded in the coecum (182 minutes), the overall shortest in the rectum (58 minutes; non-significant). The median and mean value sequence indicated a right-skewed distribution of values, reflecting that higher values for EFTR duration were spread across a wider range of values.

Median lesion size was 20 (15-25) mm length, 19 (13-24) mm width, and 3 (3-4) mm depth (assessed after resection). The top segments where patients undergoing EFTR were presenting with a lesion were the ascending colon n = 25 (24.5%), the rectum n = 20 (19.0%), and the sigmoid colon n = 17 (16.7%). Lesions in the remaining segments occurred in 11.8% to 14.7% of the patients (Table 1).

| Parameter | |

| Age | 70 (64-78) |

| Duration of EFTR (minute) | 99 (88-115) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 64 (62.7) |

| Female | 38 (37.3) |

| Location of lesion | |

| Cecum | 12 (11.8) |

| Ascending colon | 25 (24.5) |

| Transverse colon | 15 (14.7) |

| Descending colon | 13 (12.7) |

| Sigmoid colon | 17 (16.7) |

| Rectum | 20 (19.6) |

| Lesion size (n = 102) | |

| Length (mm) | 20 (15-25) |

| Width (mm) | 19 (13-24) |

| Depth (mm) | 3 (3-4) |

| Histologically complete resection | 81 (79.4) |

| Microscopic residual resection | 21 (20.6) |

| Number of patients with ≥ 1 AEs to EFTR | 33 (32.4) |

| Minor AEs to EFTR | 44 (43.1) |

| Major AEs to EFTR | 1 (0.98) |

| Section-specific frequencies of AE to EFTR in the analysis population (≥ 1 AE) | |

| Cecum | 5/12 (41.7) |

| Ascending colon | 10/25 (40.0) |

| Transverse colon | 12/15 (80.0) |

| Descending colon | 8/13 (61.5) |

| Sigmoid colon | 8/17 (47.1) |

| Rectum | 2/20 (10.0) |

The most frequent lesion types including grading for intraepithelial neoplasia (IEN) were tubular adenoma n = 32 [31.4%; low grade IEN n = 22 (68.7%); high grade IEN n = 10 (31.3%)], tubulovillous adenoma n = 29 [28.4%; low grade IEN n = 15 (51.7%); high grade IEN n = 14 (48.3%)], and adenocarcinoma n = 13 (12.7%, all high-grade IEN). Altogether, these lesion types accounted for 72.5% of all lesions, while other etiologies (NETs, serrated or villous adenoma, etc.) accounted for the remaining 27.5% (Table 2).

| Frequency | Pro-tion (%) | Low grade IEN (n) | Low grade IEN (%) | High grade IEN (n) | High grade IEN (%) | |

| Tubular adenoma | 32 | 31.4 | 22 | 68.7 | 10 | 31.3 |

| Tubulovillous adenoma | 29 | 28.4 | 15 | 51.7 | 14 | 48.3 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 13 | 12.7 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 100 |

| Sessile serrated adenoma | 9 | 8.8 | 5 | 55.6 | 3 | 33.3 |

| Neuroendocrine tumor | 6 | 5.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Villous adenoma | 2 | 1.8 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 1 | 0.98 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 |

| Other (malignant melanoma, lymphofollicular hyperplasia amyloidosis, etc.) | 10 | 9.8 | - | - | - | - |

Overall, R0 and R1 were found in 83 patients (81.4%) and 19 patients (18.6%), respectively, returning an overall technical success rate of 100.0%.

R0 resection rates were numerically highest in the rectum 17/20 (85.0%), followed by the descending colon 11/13 (84.6%) and the ascending colon 21/25 (84.0%). The numerically lowest R0 resection rates was 73.3%, which was achieved in the transverse colon (Table 3). R0 was numerically the most frequent outcome across all segments, occurring at least 3 to 4 times more frequently than R1 or worse R2 outcomes. Generalized linear modelling using logistic regression for R0 resection did not indicate any relation to the model's demographic-, procedure- or lesion-related independent variables (Table 4), but there was a non-statistically significant trend for higher R0 resection probability in rectum (OR 4.1) and cecum (OR 2.4). However, the lack of a statistical difference might be due to the relatively low numbers of EFTRs in the individual segments.

| Section | R0 | R1 |

| Cecum (n = 12) | 10 (83.3) | 2 (16.7) |

| Ascending colon (n = 25) | 21 (84.0) | 4 (16.0) |

| Transverse colon (n = 15) | 11 (73.3) | 4 (26.7) |

| Descending colon (n = 13) | 11 (84.6) | 2 (15.4) |

| Sigmoid colon (n = 17) | 13 (76.5) | 4 (23.5) |

| Rectum (n = 20) | 17 (85.0) | 3 (15.0) |

| Total (n = 102) | 83 (81.4) | 19 (18.6) |

| Estimate | SE | P value | OR | OR (95%CI low) | OR (95%CI high) | |

| Intercept | 2.52 | 2.34 | 0.28 | - | - | - |

| Age | -0.01 | 0.03 | 0.61 | 0.99 | 0.93 | 1.04 |

| Gender | -0.96 | 0.52 | 0.07 | 0.38 | 0.14 | 1.06 |

| Lesion length (mm) | -0.03 | 0.04 | 0.48 | 0.97 | 0.89 | 1.05 |

| Lesion depth (mm) | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.93 | 1.01 | 0.74 | 1.45 |

| EFTR duration (minutes) | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.02 |

| Ascending colon vs reference1 | 0.39 | 0.76 | 0.61 | 1.47 | 0.32 | 6.59 |

| Descending colon vs reference1 | 0.36 | 0.91 | 0.69 | 1.43 | 0.24 | 9.29 |

| Cecum vs reference1 | 0.89 | 0.99 | 0.36 | 2.44 | 0.38 | 21.25 |

| Sigmoid colon vs reference1 | 0.03 | 0.82 | 0.97 | 1.03 | 0.20 | 5.26 |

| Rectum vs reference1 | 1.42 | 1.02 | 0.17 | 4.12 | 0.60 | 37.81 |

33 of 102 patients experienced any type of AE to EFTR as specified above, resulting in an overall case complication rate of 32.4% (Table 5). As the total numbers across the large intestine segments show, postinterventional abdominal pain was the most frequent AE occurring in 19/102 patients (18.6%), followed by hematochezia 10/102 (9.8%), hemoglobin decline 8/102 (7.8%), and fever 7/102 (6.9%). Importantly, only one major complication (1/102 = 0.98%) was reported due to perforation of the sigmoid colon requiring immediate response by emergency surgery.

| Location | Hematochezia | Fever | Post-interventional abdominal pain | Hemoglobin decline | Severe adverse events (any) | Total no. of AE/pts with AE, (%) |

| Cecum (n = 12) | 1 (8.3) | 2 (16.6) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (8.3) | - | 5/4 (33.3) |

| Ascending colon (n = 25) | 2 (8.0) | - | 5 (20.0) | 3 (12.0) | - | 10/8 (32.0) |

| Transverse colon (n = 15) | 4 (26.7) | 2 (13.3) | 5 (33.3) | 1 (6.7) | - | 12/8 (53.3) |

| Descending colon (n = 13) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (7.7) | 4 (30.8) | 2 (15.4) | - | 8/5 (38.5) |

| Sigmoid colon (n = 17) | 2 (11.8) | 2 (11.8) | 3 (17.7) | - | 1 (5.9)1 | 8/6 (35.3) |

| Rectum (n = 20) | - | - | 1 (5.0) | 1 (5.0) | - | 2/2 (10.0) |

| Total (n = 102) (across segments) | 10 (9.8) | 7 (6.9) | 19 (18.6) | 8 (7.8) | 1 (0.98) | 45/33 (32.4) |

The individual section results revealed that the previously described pattern of AE was reflected by the relatively high numbers of the transverse colon only, with the ascending colon, the descending colon, and the sigmoid colon showing similar but not identical patterns. In detail, the sectional complication rates showed that all types of AE to EFTR were numerically most frequent in the transverse colon (53.3%), with the remaining segments of the large intestine showing the following sectional complication rates: 38.5% (descending colon), 35.3% (sigmoid colon), 33.3% (cecum), 32.0% (ascending colon) and 10.0% (rectum) (Table 5). In the transverse colon and the directly neighboring regions the numerically highest rates of AE were documented with 14/19 patients with pain (73.7%) and 7/10 patients with hematochezia (70.0%) or 6/8 patients hemoglobin decrease (75.0%).

Due to the low number of observable AE, logistic regression for AE was only interpretable for modelling the occurrence of postsurgical abdominal pain. The corresponding regression model indicated EFTR for rectal lesions to be less likely related to postsurgical abdominal pain than EFTR for lesions in the transverse colon (OR: 0.06, 95%CI: 0.003-0.60, P = 0.03). This finding was independent of the remaining variables in the model. Aside from this finding, no other variables were independently related to postsurgical abdominal pain (Supplementary Table 1). However, even if not statistically significant it should be mentioned that the segments neighboring transverse colon proximally and distally also have a relatively high frequency of post-EFTR abdominal pain (Table 5).

Only one major complication was coded as serious AE in the sigmoid colon. Thus, in our real-world analysis the perforation rate of colonic EFTR in non-selected patients amounted to 0.98%. However, this case required immediate response by emergency surgery, but no fatality occurred.

EFTR with FTRD is an efficacious and safe procedure for resecting colorectal lesions difficult to address through conventional methods like EMR or ESD. Our real-world data show that lesions suitable for EFTR can be resected on average with satisfactory outcomes, achieving histologically proven clear-resection margins (R0) for the entire colon in more than four out of five patients (i.e., 81.4%). These real-world data confirm that the results from prospective studies by experienced investigators with R0 resection rates of 75%-100%[10] translate to daily clinical practice. Regardless of study results, patients inquire about specific success and complication rates when dealing with difficult-to-resect colorectal neoplasia in specific colonic segments. Although FTRD has been approved since 2014, no data exists on EFTR difficulty in specific colorectal segments, segment-specific outcomes, or complication rates. To provide precise answers to these questions, which are essential for patient consent as well as for endoscopists' selection, education, and scheduling of an EFTR, we analyzed real-world data from 102 patients regarding differences in EFTR outcomes across colorectal segments.

Compared to the favorable resection rates for the whole colon, data from different segments of the lower GIT showed considerable topographical variance of R0 resection rates, with a maximum range exceeding 10% for efficacy (R0 transverse colon: 73.3% vs rectum 85.0%). This finding is essential for clinical practice, highlighting that the success rate of EFTR with FTRD vary across segments of the large intestine. Consequently, careful consideration of EFTR for colorectal lesions should include the likelihood of success regarding lesion type and location, as well as available methodological alternatives with their success rates, potential risks and complications. Data from large samples, meta-analyses or clinical guidelines for (underwater) EMR, ESD and laparoscopic surgery for colorectal lesions may support informed decision-making[14-20].

A conceivable explanation for varying R0 success rates may be found in the shape of the transverse and sigmoid colon. These lesions may be more challenging to access and resect due to directional shifts from the underlying anatomy. Unlike other segments that enable relatively straight advance of the endoscope or require minimal directional change, the transverse and sigmoid colon both require close attention due to two shifts each. Thus, it may be hypothesized that lesions close to required directional changes of the endoscope, such as at the passage of transverse to descending colon or ascending to transverse colon at the hepatic flexure, may be prone to unsatisfactory resection outcomes. However, neoplastic lesions at the hepatic flexure are known to be more difficult as well for conventional resection methods than other locations.

Given R0 resection rate as the primary efficacy measure in a real-world environment, our results align with a Germany study including 181 patients reporting an R0 success rate of 76.9% and with a recent meta-analysis reporting pooled R0 resection rates of 77.8% (95%CI: 74.7-80.6)[21,22]. However, compared to another systematic review from Fahmawi et al[7], our numbers fall slightly below the reported weighted pooled R0 resection rate of 82.4% (95%CI: 79.0%-85.5%)[7]. Comparison of the reviews shows that either inclusion of new data or application of different pooling methods may cause these deviating results. As our data comes from a real-world clinical environment without preselection of patients beyond standard EFTR procedures specified in the methods section, R0 rates are likely lower than those from clinical trials focusing on specific lesion types. This may also explain why our sample’s overall case complication rate (minor and major) is higher than that of the review [32.4% vs a weighted pooled rate of 10.2% (95%CI: 7.8%-12.8%)][7]. Although severe AE were rare in our sample, the frequency of minor or moderate AE needs to be addressed. From our perspective, another reasonable cause may explain this difference. In our analysis, we report the frequency of single AE to EFTR. A combination of these is referred to as post-polypectomy coagulation syndrome (PPCS) in literature. This syndrome typically includes postsurgical abdominal pain, fever, leukocytosis, and elevated inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein. In literature, it remains unclear whether PPCS is reported including all of these symptoms or just some of them. Thus, compared to studies with unclear definition of PPCS, our analysis shows higher case complication rates by reporting each single AE after EFTR for a higher level of detail. This explanation is particularly relevant when comparing our results to studies lacking information on single PPCS-related complications where “fully-blown PPCS” was absent, given the proportions of patients with postsurgical abdominal pain and fever in our sample.

Some limitations regarding the application and generalizability of our results should be considered. First, the EFTRs for this retrospective analysis were conducted in Germany, where unlike other countries, patients do not have to reimburse the full EFTR costs. In Germany, healthcare insurances usually cover a considerable proportion of these costs. With EFTR being relatively new, it might not be accessible or affordable in other countries, or the healthcare infra

Concerning post-EFTR abdominal pain, hematochezia and hemoglobin decrease, regions neighboring the transverse colon showed the highest AE rates (pain 73.6%; hematochezia 70%; hemoglobin decrease 75%). This contrasts with events in regions at the start and end of the lower GIT, cecum and rectum. While clinical experience suggested the rectum at its midth and proximally was more prone for successful and uneventful EFTR, the cecum emerged as a favorable resection site for R0 resection and AE.

Overall, EFTR is a promising approach to a large variety of colorectal lesions difficult to access or resect, with growing evidence for its efficacy and safety. Our real-world data on non-selected patients demonstrate for the first time site-specific R0 resection rate with EFTR, the higher occurrence of AE in transverse colon and neighboring segments with a low overall rate of major complications. Further studies with a similar approach may support our results, but the present findings already may be relevant for patient information, visceral medical considerations and training in this resection technique.

| 1. | Schurr MO, Baur F, Ho CN, Anhoeck G, Kratt T, Gottwald T. Endoluminal full-thickness resection of GI lesions: a new device and technique. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2011;20:189-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Schmidt A, Bauerfeind P, Gubler C, Damm M, Bauder M, Caca K. Endoscopic full-thickness resection in the colorectum with a novel over-the-scope device: first experience. Endoscopy. 2015;47:719-725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Valli PV, Kaufmann M, Vrugt B, Bauerfeind P. Endoscopic resection of a diverticulum-arisen colonic adenoma using a full-thickness resection device. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:969-971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Andrisani G, Pizzicannella M, Martino M, Rea R, Pandolfi M, Taffon C, Caricato M, Coppola R, Crescenzi A, Costamagna G, Di Matteo FM. Endoscopic full-thickness resection of superficial colorectal neoplasms using a new over-the-scope clip system: A single-centre study. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49:1009-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Aepli P, Criblez D, Baumeler S, Borovicka J, Frei R. Endoscopic full thickness resection (EFTR) of colorectal neoplasms with the Full Thickness Resection Device (FTRD): Clinical experience from two tertiary referral centers in Switzerland. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6:463-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bisogni D, Manetti R, Talamucci L, Coratti F, Naspetti R, Valeri A, Martellucci J, Cianchi F. Comparison among different techniques for en-bloc resection of rectal lesions: transanal endoscopic surgery vs. endoscopic submucosal dissection vs. full-thickness resection device with Over-The-Scope Clip® System. Minerva Chir. 2020;75:234-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fahmawi Y, Hanjar A, Ahmed Y, Abdalhadi H, Mulekar MS, Merritt L, Kumar M, Mizrahi M. Efficacy and Safety of Full-thickness Resection Device (FTRD) for Colorectal Lesions Endoscopic Full-thickness Resection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55:e27-e36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Soriani P, Tontini GE, Neumann H, de Nucci G, De Toma D, Bruni B, Vavassori S, Pastorelli L, Vecchi M, Lagoussis P. Endoscopic full-thickness resection for T1 early rectal cancer: a case series and video report. Endosc Int Open. 2017;5:E1081-E1086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Grauer M, Gschwendtner A, Schäfer C, Neumann H. Resection of rectal carcinoids with the newly introduced endoscopic full-thickness resection device. Endoscopy. 2016;48 Suppl 1:E123-E124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Albrecht H, Raithel M, Braun A, Nagel A, Stegmaier A, Utpatel K, Schäfer C. Endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR) in the lower gastrointestinal tract. Tech Coloproctol. 2019;23:957-963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Meier B, Elsayed I, Seitz N, Wannhoff A, Caca K. Efficacy and safety of combined EMR and endoscopic full-thickness resection (hybrid EFTR) for large nonlifting colorectal adenomas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;98:405-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. The R Project for Statistical Computing. Austria. [cited 23 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.R-project.org/. |

| 13. | R Studio Team. R Studio: Integrated Development for R. [cited 23 August 2025]. Available from: http://www.rstudio.com/. |

| 14. | Pimentel-Nunes P, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Ponchon T, Repici A, Vieth M, De Ceglie A, Amato A, Berr F, Bhandari P, Bialek A, Conio M, Haringsma J, Langner C, Meisner S, Messmann H, Morino M, Neuhaus H, Piessevaux H, Rugge M, Saunders BP, Robaszkiewicz M, Seewald S, Kashin S, Dumonceau JM, Hassan C, Deprez PH. Endoscopic submucosal dissection: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47:829-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 817] [Cited by in RCA: 958] [Article Influence: 87.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pellise M, Burgess NG, Tutticci N, Hourigan LF, Zanati SA, Brown GJ, Singh R, Williams SJ, Raftopoulos SC, Ormonde D, Moss A, Byth K, P'Ng H, Mahajan H, McLeod D, Bourke MJ. Endoscopic mucosal resection for large serrated lesions in comparison with adenomas: a prospective multicentre study of 2000 lesions. Gut. 2017;66:644-653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ferlitsch M, Moss A, Hassan C, Bhandari P, Dumonceau JM, Paspatis G, Jover R, Langner C, Bronzwaer M, Nalankilli K, Fockens P, Hazzan R, Gralnek IM, Gschwantler M, Waldmann E, Jeschek P, Penz D, Heresbach D, Moons L, Lemmers A, Paraskeva K, Pohl J, Ponchon T, Regula J, Repici A, Rutter MD, Burgess NG, Bourke MJ. Colorectal polypectomy and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2017;49:270-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 559] [Cited by in RCA: 797] [Article Influence: 88.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Chandan S, Khan SR, Kumar A, Mohan BP, Ramai D, Kassab LL, Draganov PV, Othman MO, Kochhar GS. Efficacy and histologic accuracy of underwater versus conventional endoscopic mucosal resection for large (>20 mm) colorectal polyps: a comparative review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94:471-482.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kamal F, Khan MA, Lee-Smith W, Khan Z, Sharma S, Tombazzi C, Ahmad D, Ismail MK, Howden CW, Binmoeller KF. Underwater vs conventional endoscopic mucosal resection in the management of colorectal polyps: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc Int Open. 2020;8:E1264-E1272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yong JN, Lim XC, Nistala KRY, Lim LKE, Lim GEH, Quek J, Tham HY, Wong NW, Tan KK, Chong CS. Endoscopic submucosal dissection versus endoscopic mucosal resection for rectal carcinoid tumor. A meta-analysis and meta-regression with single-arm analysis. J Dig Dis. 2021;22:562-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang J, Zhang XH, Ge J, Yang CM, Liu JY, Zhao SL. Endoscopic submucosal dissection vs endoscopic mucosal resection for colorectal tumors: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8282-8287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Schmidt A, Beyna T, Schumacher B, Meining A, Richter-Schrag HJ, Messmann H, Neuhaus H, Albers D, Birk M, Thimme R, Probst A, Faehndrich M, Frieling T, Goetz M, Riecken B, Caca K. Colonoscopic full-thickness resection using an over-the-scope device: a prospective multicentre study in various indications. Gut. 2018;67:1280-1289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 22. | Wannhoff A, Meier B, Caca K. Systematic review and meta-analysis on effectiveness and safety of the full-thickness resection device (FTRD) in the colon. Z Gastroenterol. 2022;60:741-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Spychalski M, Włodarczyk M, Winter K. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on endoscopic submucosal dissection outcomes in early colorectal tumours. Br J Surg. 2021;108:e224-e225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/