Published online Aug 16, 2021. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v13.i8.329

Peer-review started: December 16, 2020

First decision: March 1, 2021

Revised: April 7, 2021

Accepted: July 19, 2021

Article in press: July 19, 2021

Published online: August 16, 2021

Processing time: 238 Days and 5.9 Hours

The hemorrhoid energy treatment (HET) system is a non-surgical bipolar electrotherapy device, which has previously demonstrated efficacy in the management of bleeding Grade I and II internal hemorrhoids; however, data is limited.

To prospectively assess the safety and efficacy of the HET device.

This was an IRB-approved prospective study of 73 patients with Grade I or II internal hemorrhoids who underwent HET from March 2016 to June 2019. Patient factors and procedural data were obtained. A post-procedure questionnaire was administered by telephone to all patients at 1-wk and 3-mo following HET to assess for improvement and/or resolution of rectal bleeding and adherence to a stool softener regimen. A chart review was performed to observe recurrent symptoms and durability of response. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (IBM; SPSS Version 25.0).

Seventy-three patients underwent HET during the study period. Mean post-HET follow-up was 1.89 years. Complete resolution of bleeding was reported in 65% at 1 wk (n = 48), with improvement in bleeding in 97.2% (n = 71) of patients. At 3-mo, resolution and/or improvement in bleeding was reported in 90% (n = 64) of patients. No procedure-related pain or adverse events were reported.

HET is well tolerated, safe and highly effective in the majority of our patients presenting with Grade I and II symptomatic internal hemorrhoids.

Core Tip: Bleeding internal hemorrhoids are a very common problem. More than 50% of population 50 years or older have issues with constipation leading to painless bleeding. Tremendous amount of money is spent in urgent care and emergency department visits for painless bleeding. Not many treatment modalities are available for internal hemorrhoids. Hemorrhoid energy treatment is a bipolar equipment for treatment of internal hemorrhoids grade I and II. Our study has reflected the benefits of this device through our prospective trial.

- Citation: Kothari TH, Bittner K, Kothari S, Kaul V. Prospective evaluation of the hemorrhoid energy treatment for the management of bleeding internal hemorrhoids. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2021; 13(8): 329-335

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v13/i8/329.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v13.i8.329

Internal hemorrhoids (IH) are a very common cause of lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) with an estimated prevalence in the United States of 4.4%, accounting for an estimated 3.3 million ambulatory care visits annually[1]. Approximately 40% of patients with hemorrhoids are asymptomatic; however, those presenting with symptoms most often report painless bleeding[2]. Conventionally, Grade I and II bleeding IH have been managed with noninvasive therapies that combine dietary and lifestyle modifications, including increased oral fluid intake, reduction of fat consumption, avoidance of straining during bowel movements, and increased fiber intake[3].

For symptomatic patients, several non-surgical outpatient office-based treatments are currently available including rubber band ligation, infrared coagulation, sclerotherapy, bipolar diathermy, laser photocoagulation, and sclerotherapy[4]. The goal of non-surgical treatment is to decrease vascularity, reduce redundant tissue, and increase hemorrhoidal rectal wall fixation to minimize prolapse[3]. Though success has been demonstrated with the above-mentioned techniques, anorectal pain, recurrent bleeding, and recurrence of hemorrhoids are well-reported adverse events[5,6].

A novel non-surgical bipolar electrotherapy device, the hemorrhoid energy treatment (HET) System, has previously demonstrated efficacy in the management of bleeding Grade I and II IH[7,8]. We present a prospective study to date evaluating the efficacy and safety of HET.

This was an IRB-approved prospective cohort study (Research Subjects Review Board, University of Rochester, Study #780) conducted at our tertiary care referral center from 03/2016 to 06/2019. Adult patients (≥ 18 years old) with Grade I or Grade II IH scheduled for outpatient treatment with the HET system during the study period were eligible for inclusion. Written informed consent was obtained prior to study enrollment. All enrolled patients were contacted at 1-week post-procedure to assess improvement in rectal bleeding and self-reported compliance with stool softener use. At 3-mo post-procedure, the same survey was administered by telephone to evaluate if resolution or improvement in rectal bleeding had changed, and if compliance with stool softener use continued. All follow-up questionnaires were administered by telephone by one of the authors (Bittner K) utilizing a standardized script for each call. A concurrent chart review was performed to collect patient demographics, procedural and clinical data. All pre- and post-HET office visits with documented occurrences of bleeding attributed to IH were recorded. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software (IBM, SPSS Version 25.0; Armonk, NY, United States).

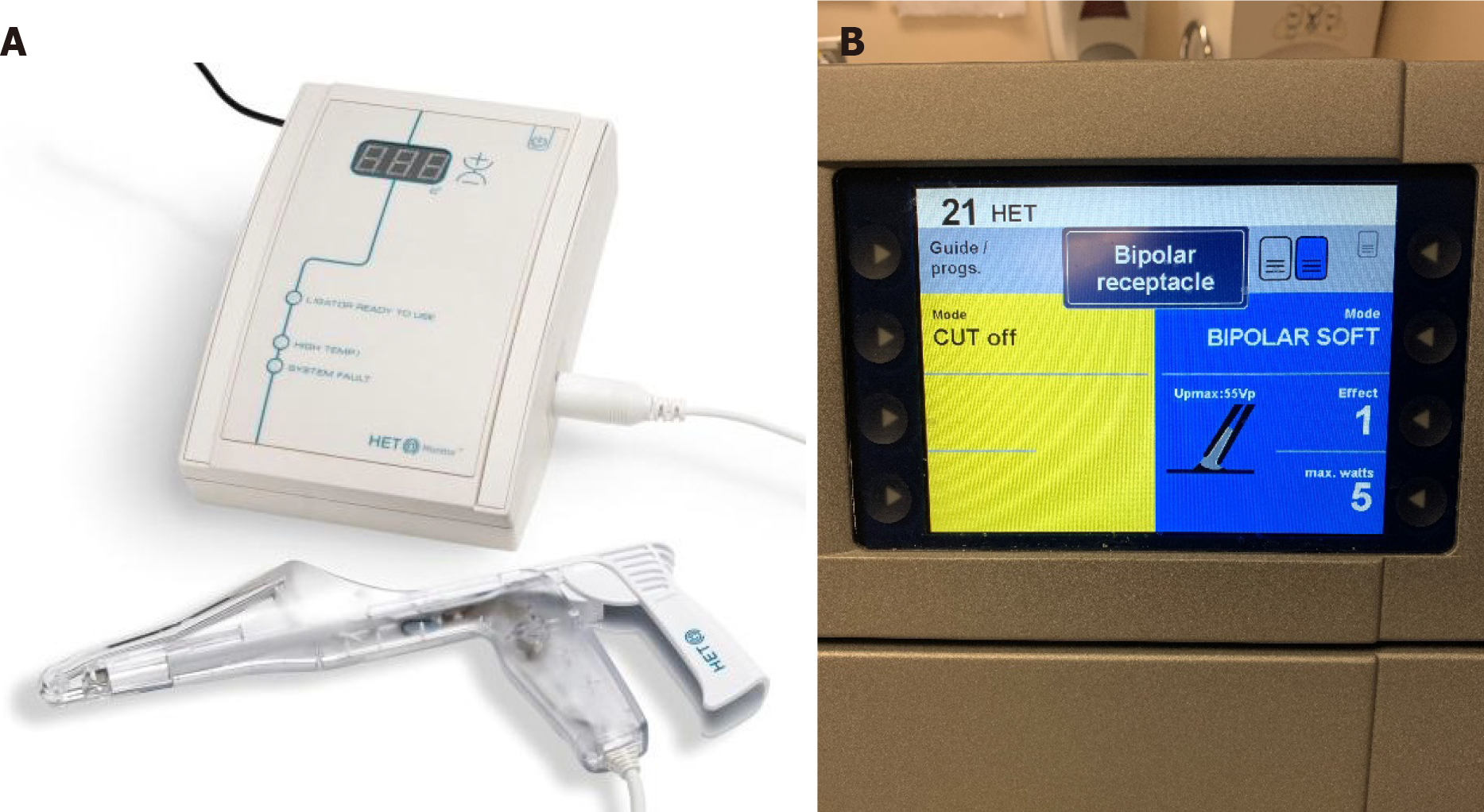

The HET Bipolar System (Medtronic, United States) is a modified anoscope, which incorporates bipolar forceps and incudes a separate tissue temperature monitor console (Figure 1). HET was utilized with a commercially available electrosurgical generator (ERBE; Marietta, GA, United States)[9]. Ablation of IH can be achieved with the use of one of three techniques. All HET procedures were performed by two advanced endoscopists (TK, VK), with an average procedure time of less than 15 min.

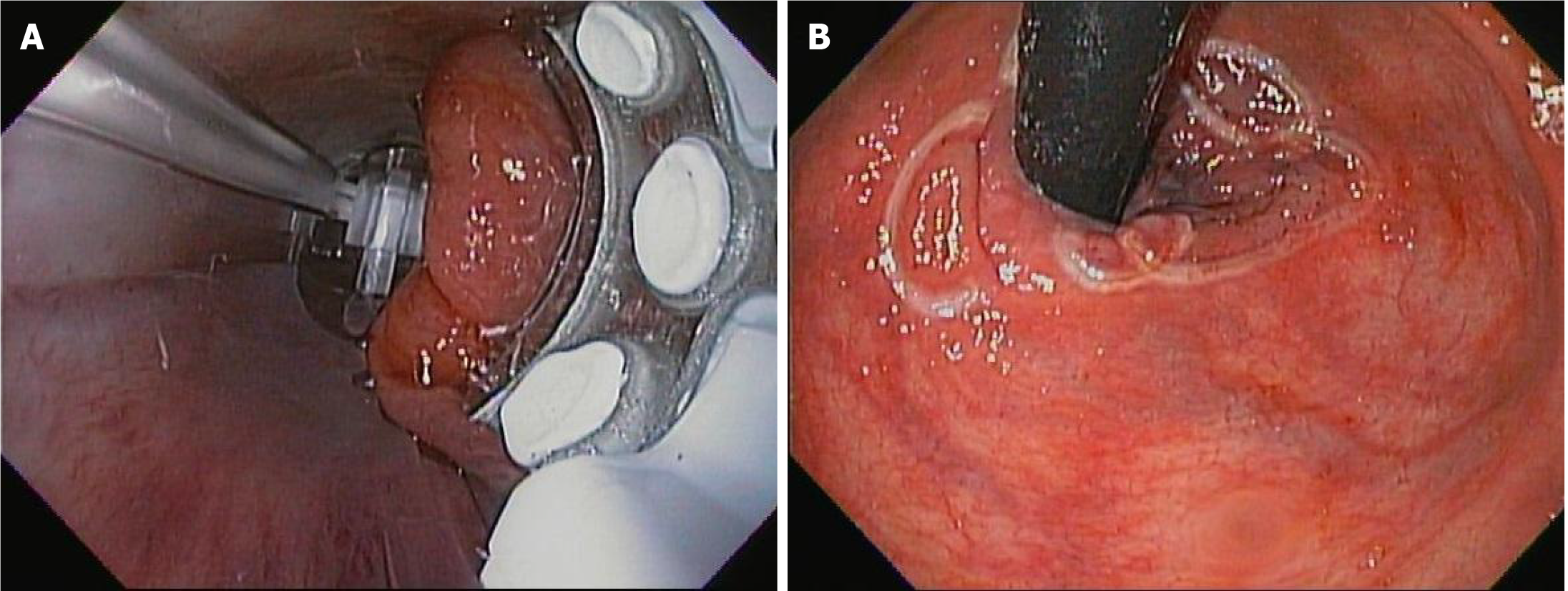

Medtronic anoscopy technique: This technique includes insertion of the bipolar forceps under LED light provided at the top of the forceps and performing the procedure under direct vision. The superior hemorrhoidal plexus area, approximately 1 cm above the proximal extent of the IH, was grasped with the bipolar forceps. After confirming that the tissue grasped is sufficient (by means of same level approximation of three red lines on bipolar forceps handle), bipolar current was applied with using the recommended electrosurgical generator coagulation settings (effect 1, 5 watts; Figure 2A).

Standard technique: Our “standard technique” included the use of gastroscope inside the bipolar forceps to perform the IH ablation under endoscopic vision (Figure 2B). The concept is to target the superior hemorrhoidal plexus. This method was utilized for the majority of patients in our study (n = 70/73).

Modified technique: At our center, we developed a technique called the “modified HET technique” that utilizes use of pediatric biopsy forceps for tissue grasping in addition to the use of the standard endoscope to guide the bipolar forceps. This modified technique facilitates the capture of target rectal tissue when flat and difficult to grasp with the bipolar forceps alone. The pediatric biopsy forceps are used to gently pull the tissue immediately proximal to the IH, which allows the superior hemorrhoidal plexus area to enter the forceps better for optimal treatment (Figure 3).

A total of 73 patients were enrolled during the study period (March 2016 through June 2019). The majority of patients were female (53.4%), with mean age of 50.3 years (Table 1). Mean follow-up duration (post-HET) was 1.89 years. Thirty-six patients (49.3%) presented with Grade I and twenty-six (35.6%) with Grade II IH. Grade of IH was not available for 10/73 (13.7%) patients. In one patient, a Grade III hemorrhoid confirmed on colonoscopy immediately prior to treatment. Approximately half of patients (45.2%) failed conservative therapy prior to HET (defined as: stool softeners, fiber supplements and/or hydrocortisone suppositories). Most patients (90.4%) reported persistent painless rectal bleeding at the office visit immediately prior to referral for HET.

| Patient characteristics | n = 73 |

| Age at HET (yr), mean | 50.3 |

| Female, n (%) | 39 (53.4) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 58 (79.5) |

| African-American | 14 (19.2) |

| Asian | 1 (1.4) |

| Grade of hemorrhoids at time of HET, n (%) | |

| Grade I | 36 (49.3) |

| Grade II | 26 (35.6) |

| Grade III | 1 (1.4) |

| Not reported | 10 (13.7) |

HET was performed with flexible sigmoidoscopy in all cases, using a standard gastroscope. Our “standard HET technique” was utilized in 70/73 patients. Three patients were treated with the “modified HET technique”. All patients were contacted by telephone at 1-wk and 3-mo post-procedure (Tables 2 and 3) to complete a questionnaire regarding resolution and/or improvement of bleeding symptoms, and compliance with stool softener use. All patients successfully completed the 1-wk questionnaire; however, 2 patients were unable to be contacted at 3-mo (response rate = 100% and 97.3%, respectively). At 1-wk post-procedure, complete resolution of bleeding was reported in 66% of patients (n = 48/73), with improvement in bleeding reported in 97.2% (n = 71/73) patients. Polyethylene glycol and/or other stool softeners were prescribed post-procedure to prevent constipation; however, at 3-mo post-HET, only 55% of patients reported continued use.

| Responses to telephonic questionnaire, 1 wk post-procedure (n = 73) | |||||

| Bleeding resolved | Bleeding improved | Use of stool softeners (post-HET) | |||

| Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) |

| 48 (65.8) | 25 (34.2) | 23 (92.0) | 2 (8.0) | 36 (49.3) | 37 (50.7) |

A concurrent chart review was performed to assess for recurrence or persistence of symptoms and durability of response. At 3-mo post-procedure, complete resolution of bleeding was reported in 62% of patients (n = 44/71), with improvement in bleeding reported in 90.1% (n = 64/71) patients. Six patients required a repeat HET (mean of 7.6 mo following initial treatment) for persistent rectal bleeding, with complete resolution reported after the 2nd treatment in 3/6 of these patients. Three patients continued to report persistent rectal bleeding despite repeat HET.

There were no instances of pain or rectal discomfort during or immediately following the HET procedure. One patient reported self-limited post-procedure bleeding. No other adverse events were noted from the procedure.

IH are common and can be symptomatic with rectal bleeding in many patients. They are often difficult to treat and can lead to significant morbidity, affect quality of life of the patient and put a significant burden on healthcare. Several non-surgical treatment modalities are available for treatment of Grade I and II bleeding IH. Current treatment guidelines recommend outpatient office-based procedures such as rubber-band ligation (RBL), sclerotherapy or infrared coagulation for patients who remain symptomatic after lifestyle modifications have failed[10].

Rubber band ligation is the most frequently used procedure for hemorrhoid treatment. In a meta-analysis of 18 randomized controlled trials, RBL was noted to have a lower need for repeat treatments compared to sclerotherapy and infrared coagulation, although did cause significantly more pain reported in 25%-50% of patients[11-13].

Sclerotherapy is one of the oldest non-surgical therapy and involves injecting a sclerosant into the submucosa at the base of the hemorrhoid. Due to the nature of the procedure, there have been adverse events reported such as rectal fistulas and life-threatening retroperitoneal sepsis[14]. In a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies comparing RBL, sclerotherapy and surgery, sclerotherapy was less effective than rubber band ligation and surgery. Infrared coagulation is less effective than banding or sclerotherapy and requires repeat treatment sessions[11].

HET is a novel non-surgical treatment for IH and has been reported to be both safe and effective in prior studies[7-9]. These studies have had limitations due to the retrospective nature of the study and small sample size. Piskun and Tucker[9] performed a direct comparison of the HET system with infrared coagulation in a live porcine model with favorable outcomes. The HET device combined target tissue compression with precise application of much lower temperature (55 °C) vs that of the infrared coagulation probe (149 ± 11.1 °C), minimizing heat-related collateral damage to tissues adjacent to the treatment areas. The authors concluded that the treatment with the HET System would cause less procedural pain and less post-procedural adverse events vs existing non-surgical modalities for treatment of IH[9]. In 2013, Kantsevoy and Bitner[8] conducted a retrospective study of examining the use of HET for the indication of actively bleeding IH. All patients in this cohort (n = 23) tolerated the treatment without any pain or discomfort. No adverse events were reported in the study[8]. In 2016, Crawshaw et al[7] reported the safety and efficacy of HET technology in a prospective case series of 20 patients with bleeding improvement seen in > 80% of the patients.

Our study demonstrates the safety and efficacy of the HET platform in the treatment of Grade I and Grade II IH. Nearly half of patients had failed guideline-based conservative therapy prior to referral for HET. The majority of our cohort reported no immediate post-procedural pain or bleeding. Complete resolution and/or improvement in bleeding symptoms were reported in 97.2% and 90.1 % of patients at 1-week and 3-months post-procedure, respectively.

The main limitations of this study were relatively small sample size (n = 73), lack of comparison or control arm, and is our single-center’s experience with HET use. The potential for lack of generalizability may exist due to the level of expertise of the endoscopists performing the HET procedure at our institution.

Our study represents one of the largest prospective studies reporting safety and efficacy for the use of HET system in patients with symptomatic Grade I and II IH. Further multi-center prospective studies are needed to validate the efficacy and safety of the device. In addition, these studies should also assess if the use of stool softeners for a brief period post-HET prevents recurrence of rectal bleeding.

Painless rectal bleeding (i.e., Grade I and Grade II Internal hemorrhoids) can be effectively treated with hemorrhoid energy treatment (HET). Our study has demonstrated that the procedure is safe, well tolerated and clinically effective for most patients.

There has been limited treatment for internal hemorrhoids, hence this manuscript is intended to add real-world clinical data to the literature.

To educate readers with clinical data regarding treatment of bleeding internal hemorrhoids with the help of HET system.

This research study was a prospective cohort design.

The majority of patients reported complete resolution and/or improvement in bleeding resulting from internal hemorrhoids at 3-mo post-procedure.

HET system can make a significant impact in treatment of bleeding internal hemorrhoids.

Further research should be performed to expand upon our findings.

| 1. | Johanson JF, Sonnenberg A. The prevalence of hemorrhoids and chronic constipation. An epidemiologic study. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:380-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Riss S, Weiser FA, Schwameis K, Riss T, Mittlböck M, Steiner G, Stift A. The prevalence of hemorrhoids in adults. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:215-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sun Z, Migaly J. Review of Hemorrhoid Disease: Presentation and Management. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2016;29:22-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ohning GV, Machicado GA, Jensen DM. Definitive therapy for internal hemorrhoids--new opportunities and options. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2009;9:16-26. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Hardy A, Chan CL, Cohen CR. The surgical management of haemorrhoids--a review. Dig Surg. 2005;22:26-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Macrae HM, Temple LKF, McLeod RS. A Meta-Analysis of Hemorrhoidal Treatments. Semin Colon Rect Surg. 2002;13:77-83. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Crawshaw BP, Russ AJ, Ermlich BO, Delaney CP, Champagne BJ. Prospective Case Series of a Novel Minimally Invasive Bipolar Coagulation System in the Treatment of Grade I and II Internal Hemorrhoids. Surg Innov. 2016;23:581-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kantsevoy SV, Bitner M. Nonsurgical treatment of actively bleeding internal hemorrhoids with a novel endoscopic device (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:649-653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Piskun G, Tucker R. New bipolar tissue ligator combines constant tissue compression and temperature guidance: histologic study and implications for treatment of hemorrhoids. Med Devices (Auckl). 2012;5:89-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wald A, Bharucha AE, Cosman BC, Whitehead WE. ACG clinical guideline: management of benign anorectal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1141-57; (Quiz) 1058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | MacRae HM, McLeod RS. Comparison of hemorrhoidal treatment modalities. A meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:687-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 333] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 12. | Shanmugam V, Thaha MA, Rabindranath KS, Campbell KL, Steele RJ, Loudon MA. Systematic review of randomized trials comparing rubber band ligation with excisional haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1481-1487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Sajid MS, Bhatti MI, Caswell J, Sains P, Baig MK. Local anaesthetic infiltration for the rubber band ligation of early symptomatic haemorrhoids: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Updates Surg. 2015;67:3-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Barwell J, Watkins RM, Lloyd-Davies E, Wilkins DC. Life-threatening retroperitoneal sepsis after hemorrhoid injection sclerotherapy: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:421-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American College of Gastroenterology; American Gastroenterological Association; American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Lan C S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LYT