Published online Dec 28, 2017. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v9.i36.1367

Peer-review started: July 30, 2017

First decision: October 9, 2017

Revised: November 16, 2017

Accepted: December 6, 2017

Article in press: December 7, 2017

Published online: December 28, 2017

Processing time: 117 Days and 20.3 Hours

Liver injury in the setting of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is more commonly attributed to viral hepatitis or highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART) toxicity. The severity of liver injury is an important cause of morbidity and mortality. The emergence of autoimmune diseases, particularly autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) in the setting of HIV infection, is rare. Previous reports indicate that elevated liver enzymes are a common denominator amongst these patients. We present two patients with HIV infection, on HAART, with virological suppression. Both patients presented with elevated liver enzymes, and following liver biopsies, were diagnosed with AIH. The clinical course of these patients underscore the therapeutic value of corticosteroids, and in some cases, addition of immunosuppression for AIH treatment.

Core tip: Liver damage is rarely caused by autoimmune disease in the setting of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. We describe a case series of two patients with a history of HIV, who presented with characteristic elevation in liver enzymes. Both patients were hepatitis C negative. Liver biopsies followed by histopathology confirmed the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Case 1 was treated by corticosteroids and azathioprine, while case 2 was treated by corticosteroids only. Both patients reported significant clinical improvement. These cases suggest that liver biopsy should be performed in HIV patients with unknown liver disease. Additionally, they underscore the need for further clinical studies to explore the role of corticosteroids and immunosuppression in the management of autoimmune hepatitis in HIV patients.

- Citation: Ofori E, Ramai D, Ona MA, Reddy M. Autoimmune hepatitis in the setting of human immunodeficiency virus infection: A case series. World J Hepatol 2017; 9(36): 1367-1371

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v9/i36/1367.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v9.i36.1367

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a rare chronic liver disease which was first reported in the 1950s by the Swedish physician Jan Waldstrom[1]. Patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) tend to have impaired immune systems, weakening host defenses against opportunistic pathogens, and autoimmunity[2]. Given that complications of liver disease in the setting of HIV are more likely due to coinfections with hepatitis B (HBV) or hepatitis C (HCV) viruses, antiretroviral drug toxicity, opportunistic infections, or neoplastic disorders, it is very rare to encounter cases of AIH. While the global occurrence of AIH is largely unknown, in Europe and North America it has been estimated at 1.9/100000 incidence and 16.9/100000 prevalence[3]. A review of the literature shows that only 18 cases (excluding our two patients) have been reported[4-11]. Herein, we present two cases of AIH in the setting of HIV infection.

A 40-year-old male who emigrated from Guyana, diagnosed with HIV since 2009 and started on efavirenz, emtricitabine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (Atripla), with viral suppression and immunological recovery (CD4 cell count 832/mm3), presented for a follow-up. He was a non-smoker with prior history of alcohol consumption and liver cirrhosis. Laboratory workup showed elevated liver enzymes of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 302 U/L, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 149 U/L. These values decreased over the next 3 mo and increased again, reaching their highest at 14 mo: ALT 465 U/L, and AST 302 U/L. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) was elevated at 233 U/L, total bilirubin 1.3 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 0.6 mg/dL, and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) 14 ng/mL.

To elucidate the etiology of elevated transaminases, further laboratory tests were performed. He was immune to HBV virus, nonreactive for HCV antibody and undetected by quantitative PCR assay. White cell count, hemoglobin, hematocrit, platelets, prothrombin time, INR, and albumin were all within normal limits. Iron and copper metabolism in addition to ceruloplasmin and alpha-1-antitrypsin levels were also normal. Autoimmune assay for antinuclear antibodies (ANA) was negative, and smooth muscle antibody (ASMA) immunoglobulin G (IgG) was positive at 60 Units (normal 0-19 Units), suggestive of autoimmune hepatitis. Hemochromatosis gene mutations (H63D and C282Y) screening were negative. IgG level was 2740 mg/dL.

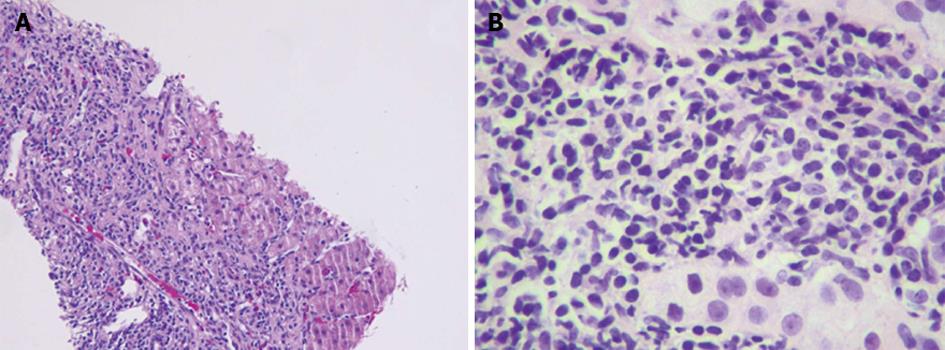

Abdominal ultrasound showed a normal sized liver with slight heterogeneity, suggestive of diffuse liver disease. Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed obstruction of the right hepatic tip by a blooming artifact of uncertain etiology. A transthoracic percussion guided liver biopsy was performed without complications. Histopathology showed fibrous portal expansion and bridging fibrosis. Portal and periportal inflammatory activity along with piecemeal necrosis was identified (Figure 1). Taken in clinical context, the diagnosis of AIH was confirmed. The patient was started on corticosteroids, and was later prescribed Azathioprine.

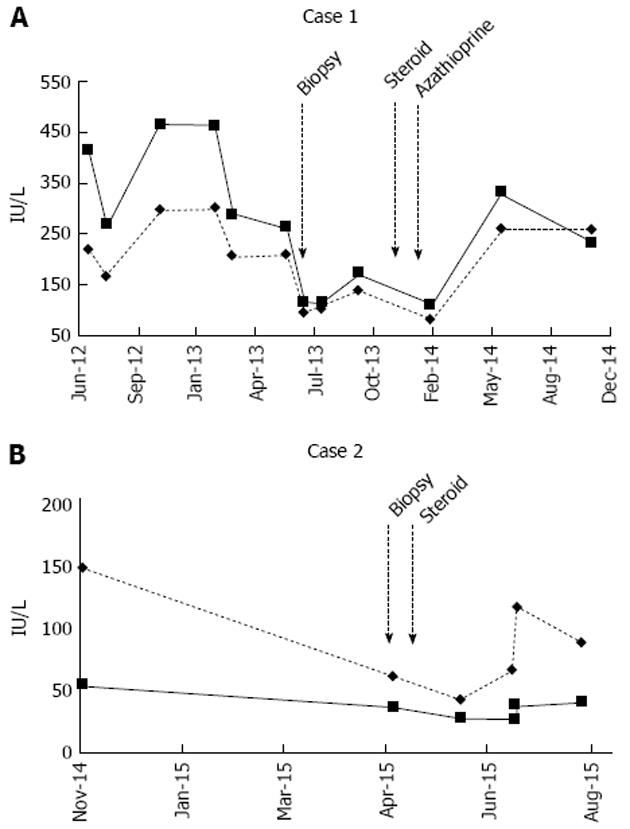

The patient was lost to follow-up, but presented 18 mo later and showed a notable improvement in liver enzymes: ALT 112 U/L, and AST 81 U/L. He reported no new symptoms related to liver disease. However, the patient was non-compliant with his medications and repeated laboratory results showed rising liver transaminases again (Figure 2A). The patient was advised to restart his medications.

A 44-year-old Hispanic female diagnosed with HIV since 1997 and started on Atripla since 2010 with viral suppression and immunological recovery (CD4 count 823, and viral load undetectable), was admitted for epigastric pain and vomiting. A non-smoker, laboratory workup showed elevated liver chemistries: ALT 155 U/L, AST 136 U/L, ALP 100 U/L, total bilirubin 1.9 mg/dL, AFP 16 ng/mL. She was immune to Hepatitis A (HAV) and HBV, and non-reactive for HCV. ANA (1:640), and ASMA (1:180), were positive suggestive of AIH. Abdominal MRI showed perihepatic fluid and cirrhosis of the liver. Esophagastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed a gastric ulcer, which was positive for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) gastritis. Colonoscopy revealed a tubular adenoma. The patient was stabilized and discharged after 6 d.

A liver biopsy was performed without complications. Histopathology showed confluent necrosis infiltrated by dense lympho plasmacytic infiltrates partially replaced by fibrous tissue, as well as bridging fibrous septa that enclosed regenerative nodules, consistent with AIH. The patient was started on prednisone. At the 6th week of steroid therapy, the patient reported notable improvement in symptoms, and resolving liver enzyme levels (Figure 2B).

HIV is associated with the development of autoimmune disorders such as immune thrombocytopenic purpura, inflammatory myositis, sarcoidosis, Guillain Barre Syndrome, myasthenia gravis, Graves’ disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Hashimoto thyroiditis, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, and very rarely, autoimmune hepatitis[12]. Due to its rarity, AIH in the setting of HIV is not often suspected by clinicians, but should be considered when all other etiologies are ruled out.

There are two clinically relevant types of AIH; namely, type 1 and type 2. Type 1 AIH is referred to as the classic type, typically diagnosed in adulthood, whereas type 2 is diagnosed during childhood[13,14]. Though both types are similar, type 2 AIH can be more severe and difficult to manage. Symptoms associated with AIH include fatigue, pruritus, jaundice, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, weight loss, light colored stools, dark colored urine, joint pain, rashes, and loss of menstruation in women[4-11,15,16]. Without adequate therapy, the disease can progress in the form of liver fibrosis. As a result, patients can develop cirrhosis, liver failure, ascites, gastrointestinal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, and even hepatocellular carcinoma.

The diagnosis of AIH is established based on the following criteria by the American and European practice guidelines: Hyper-gammaglobulinemia, positive serologic tests including antinuclear and anti-smooth muscle antibodies, and a characteristic hepatic histological appearance, namely interface hepatitis, plasmacytic infiltrate, and regenerative liver-cell rosettes[17]. Other liver diseases such as alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson disease, hemochromatosis, viral hepatitis, drug-induced liver injury, and alcoholic/nonalcoholic liver disease should be ruled out.

The diagnosis of AIH in HIV infected patients pose a diagnostic conundrum because HIV infection is usually considered as being protective against autoimmunity. However, several mechanisms have been proposed by which HIV may subvert and influence host immune regulation. Firstly, it is thought that viral infection triggers a pro-inflammatory milieu, which overrides host regulatory networks. This may lead to the generation of self-perpetuating autoimmune reactions[18]. Genetic susceptibility has also been proposed as an alternative mechanism. AIH is a polygenetic disorder with strong evidence of inheritability. During the maturation of T-cells, the thymus deletes T-cells that react too strongly to self-antigens[19]. Thymic mutations can indeed affect this process and lead to AIH. Furthermore, despite thymic selection, individuals who express HLA haplotypes DR3, DR4, and hepatocyte enzyme CYP2D6, are more likely to develop AIH[20-23].

Another suggested mechanism is the role of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), also known as immune restoration disease. While the pathogenesis of IRIS is speculative, it is thought to occur in patients with significant increase in CD4 cells after initiation of anti-retroviral (ARV) therapy, specifically those who concurrently had low CD4 cells prior to treatment[24,25]. It has been noted that the increase in CD4 count may not be responsible for the inflammatory response, but instead may be due to preexisting perturbations in T-regulatory cells (Tregs), and proinflammatory and regulatory responses such as cytokine imbalances that may significantly contribute to the onset of the syndrome after the initiation of ARV therapy[26].

As far as we know, there are no guidelines for the treatment of AIH in HIV patients. A review of published cases showed that corticosteroids and immunosuppression were reasonably used by other clinicians[4-11]. Case 1 involved the use of corticosteroids and azathioprine, while case 2 used corticosteroids only. While both cases showed resolution of symptoms, it also suggested that additional immunological suppression with azathioprine may not be required for treating AIH.

In conclusion, AIH is a rare and chronic liver disease which seldom presents in HIV-infected patients. A characteristic elevation in liver enzymes is commonly reported in these cases. However, they are often attributed to HAART or other possible liver diseases, particularly viral hepatitis. For this reason, liver biopsies should be performed in HIV patients with an unknown liver disease etiology. Furthermore, patients with AIH in the setting of HIV infection should be treated with corticosteroids. Further research is needed to study the efficacy of corticosteroids with or without the use of immunosuppression.

Case 1: A 40-year-old male diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) since 2009 and started on Atripla, with viral suppression and immunological recovery, presented for a follow-up. Case 2: A 44-year-old Hispanic female diagnosed with HIV since 1997 and started on Atripla since 2010, with viral suppression and immunological recovery, was admitted for epigastric pain and vomiting.

Case 1: Abdominal ultrasound showed a normal sized liver with slight heterogeneity, suggestive of diffuse liver disease. Case 2: An abdominal magnetic resonance (MRI) imaging was suggestive of cirrhosis of the liver.

Liver cirrhosis, hepatitis, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Case 1: Laboratory workup showed elevated liver chemistries: Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 302 U/L, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 149 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 233 U/L, total bilirubin 1.3 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 0.6 mg/dL, and alpha-fetoprotein 14 ng/mL. Case 2: Laboratory workup showed elevated liver chemistries: ALT 155 U/L, AST 136 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 100 U/L, total bilirubin 1.9 mg/dL, and alpha-fetoprotein 16 ng/mL.

Abdominal MRI imaging was suggestive of liver cirrhosis of uncertain etiology.

Case 1: A transthoracic percussion guided liver biopsy showed fibrous portal expansion, bridging fibrosis, and portal and periportal inflammatory activity with piecemeal necrosis, consistent with autoimmune hepatitis (AIH). Case 2: Liver biopsy showed confluent necrosis infiltrated by dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates partially replaced by fibrous tissue, as well as bridging fibrous septa that enclosed regenerative nodules, consistent with AIH.

Case 1 was treated with corticosteroids and azathioprine, while case 2 was treated with corticosteroids only.

Review of the literature shows that only 18 cases (excluding our two patients) have been reported.

The occurrence of autoimmune hepatitis in the setting of HIV-infected patients is an extremely rare clinical entity. The global prevalence of AIH is largely unknown. Currently, there are no standardized treatment for AIH.

This report suggest that liver biopsies should be performed in HIV patients with an unknown liver disease etiology. HIV patients diagnosed with AIH should be treated with corticosteroids. Further research is needed to study the clinical efficacy of corticosteroids with or without the use of immunosuppression.

| 1. | Leber WJ. Blutproteine und Nahrungseiweiss. Deutsch Z Verdau Stoffwechselk. 1950;15:113-119. |

| 2. | Elhed A, Unutmaz D. Th17 cells and HIV infection. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2010;5:146-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Boberg KM. Prevalence and epidemiology of autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2002;6:635-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kia L, Beattie A, Green RM. Autoimmune hepatitis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV): Case reports of a rare, but important diagnosis with therapeutic implications. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e6011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Puius YA, Dove LM, Brust DG, Shah DP, Lefkowitch JH. Three cases of autoimmune hepatitis in HIV-infected patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:425-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wan DW, Marks K, Yantiss RK, Talal AH. Autoimmune hepatitis in the HIV-infected patient: a therapeutic dilemma. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23:407-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | O’Leary JG, Zachary K, Misdraji J, Chung RT. De novo autoimmune hepatitis during immune reconstitution in an HIV-infected patient receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:e12-e14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | German V, Vassiloyanakopoulos A, Sampaziotis D, Giannakos G. Autoimmune hepatitis in an HIV infected patient that responded to antiretroviral therapy. Scand J Infect Dis. 2005;37:148-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Parekh S, Spiritos Z, Reynolds P, Samir P, Perricone A, Quigley B. HIV and Autoimmune Hepatitis: A Case Series and Literature Review. J Biomedical Sci. 2017;6:2. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Daas H, Khatib R, Nasser H, Kamran F, Higgins M, Saravolatz L. Human immunodeficiency virus infection and autoimmune hepatitis during highly active anti-retroviral treatment: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Coriat R, Podevin P. Fulminant autoimmune hepatitis after successful interferon treatment in an HIV-HCV co-infected patient. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:208-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Virot E, Duclos A, Adelaide L, Miailhes P, Hot A, Ferry T, Seve P. Autoimmune diseases and HIV infection: A cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e5769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (10)] |

| 13. | Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, Bianchi L, Burroughs AK, Cancado EL, Chapman RW, Cooksley WG, Czaja AJ, Desmet VJ. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:929-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2003] [Cited by in RCA: 2017] [Article Influence: 74.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bridoux-Henno L, Maggiore G, Johanet C, Fabre M, Vajro P, Dommergues JP, Reinert P, Bernard O. Features and outcome of autoimmune hepatitis type 2 presenting with isolated positivity for anti-liver cytosol antibody. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:825-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nikias GA, Batts KP, Czaja AJ. The nature and prognostic implications of autoimmune hepatitis with an acute presentation. J Hepatol. 1994;21:866-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Burgart LJ, Batts KP, Ludwig J, Nikias GA, Czaja AJ. Recent-onset autoimmune hepatitis. Biopsy findings and clinical correlations. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:699-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2015;63:971-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 659] [Cited by in RCA: 888] [Article Influence: 80.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Oo YH, Hubscher SG, Adams DH. Autoimmune hepatitis: new paradigms in the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Hepatol Int. 2010;4:475-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Anderson G, Jenkinson WE, Jones T, Parnell SM, Kinsella FA, White AJ, Pongrac’z JE, Rossi SW, Jenkinson EJ. Establishment and functioning of intrathymic microenvironments. Immunol Rev. 2006;209:10-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Czaja AJ, Santrach PJ, Breanndan Moore S. Shared genetic risk factors in autoimmune liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:140-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. Immunological liver diseases in children. Semin Liver Dis. 1998;18:271-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Löhr HF, Schlaak JF, Lohse AW, Böcher WO, Arenz M, Gerken G, Meyer Zum Büschenfelde KH. Autoreactive CD4+ LKM-specific and anticlonotypic T-cell responses in LKM-1 antibody-positive autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 1996;24:1416-1421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Donaldson PT. Genetics in autoimmune hepatitis. Semin Liver Dis. 2002;22:353-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Battegay M, Nüesch R, Hirschel B, Kaufmann GR. Immunological recovery and antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:280-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Shelburne SA, Visnegarwala F, Darcourt J, Graviss EA, Giordano TP, White AC Jr, Hamill RJ. Incidence and risk factors for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome during highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2005;19:399-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 440] [Cited by in RCA: 435] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Shankar EM, Vignesh R, Velu V, Murugavel KG, Sekar R, Balakrishnan P, Lloyd CA, Saravanan S, Solomon S, Kumarasamy N. Does CD4+CD25+foxp3+ cell (Treg) and IL-10 profile determine susceptibility to immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) in HIV disease? J Inflamm (Lond). 2008;5:2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Kaya M, Maggi F, McQuillan GM, Rajeshwari K S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D