Published online Dec 28, 2017. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v9.i36.1361

Peer-review started: August 25, 2017

First decision: November 1, 2017

Revised: November 22, 2017

Accepted: December 7, 2017

Article in press: December 8, 2017

Published online: December 28, 2017

Processing time: 124 Days and 8.4 Hours

De-novo malignancies carry an incidence ranging between 3%-26% after transplant and account for the second highest cause of post-transplant mortality behind cardiovascular disease. While the majority of de-novo malignancies after transplant usually consist of skin cancers, there has been an increasing rate of solid tumor cancers over the last 15 years. Although, recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is well understood among patients transplanted for HCC, there are increasing reports of de-novo HCC in those transplanted for a non-HCC indication. The proposed pathophysiology for these cases has been mainly connected to the presence of advanced graft fibrosis or cirrhosis and always associated with the presence of hepatitis B or C virus. We report the first known case of de-novo HCC in a recipient, 14 years after a pediatric living related donor liver transplantation for end-stage liver disease due to biliary atresia without the presence of hepatitis B or C virus before and after transplant. We present this case report to increase the awareness of this phenomenon and address on the utility for screening and surveillance of hepatocellular carcinoma among these individuals. One recommendation is to use similar guidelines for screening, diagnosis, and treatment for HCC as those used for primary HCC in the pre-transplant patient, focusing on those recipients who have advanced fibrosis in the allograft, regardless of etiology.

Core tip:De-novo hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a rare event compared to other de-novo malignancies, although the number of reported cases are increasing. The pathophysiology has been related with advanced graft fibrosis, cirrhosis and hepatitis viral serology. We report the first case of De-novo HCC 14 years after living related donor liver transplantation for end-stage liver disease due to biliary atresia without positive hepatitis B or C viral serology. Current screening and treatment guidelines have not been well established. This increasing phenomenon challenges us to define the utility of screening and surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma in these individuals.

- Citation: Torres-Landa S, Muñoz-Abraham AS, Fortune BE, Gurung A, Pollak J, Emre SH, Rodriguez-Davalos MI, Schilsky ML. De-novo hepatocellular carcinoma after pediatric living donor liver transplantation. World J Hepatol 2017; 9(36): 1361-1366

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v9/i36/1361.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v9.i36.1361

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common primary malignancy of the liver, is one of the most lethal and prevalent cancers worldwide. However, the use of liver transplantation (LT) is a well proven treatment approach for patients with low stage tumor. The pathogenesis of HCC typically involves chronic liver injury with regeneration, fibrosis and cirrhosis leading to dysplasia within regenerating nodules with an end result of malignancy[1]. HCC development in a liver allograft occurs most often in the setting of prior HCC where it is defined as recurrence[2]. De-novo tumor formation that arises in the transplanted graft without evidence of tumor in the previously explanted liver is uncommon and is mainly seen in patients with advanced graft fibrosis or cirrhosis and associated with the presence of hepatitis B or C viral infection[3]. The literature reveals only 15 documented cases of de-novo HCC after LT[4-15]. We report the first case of de-novo HCC occurring 14 years after a pediatric patient received a living related donor LT for end stage liver disease secondary to biliary atresia.

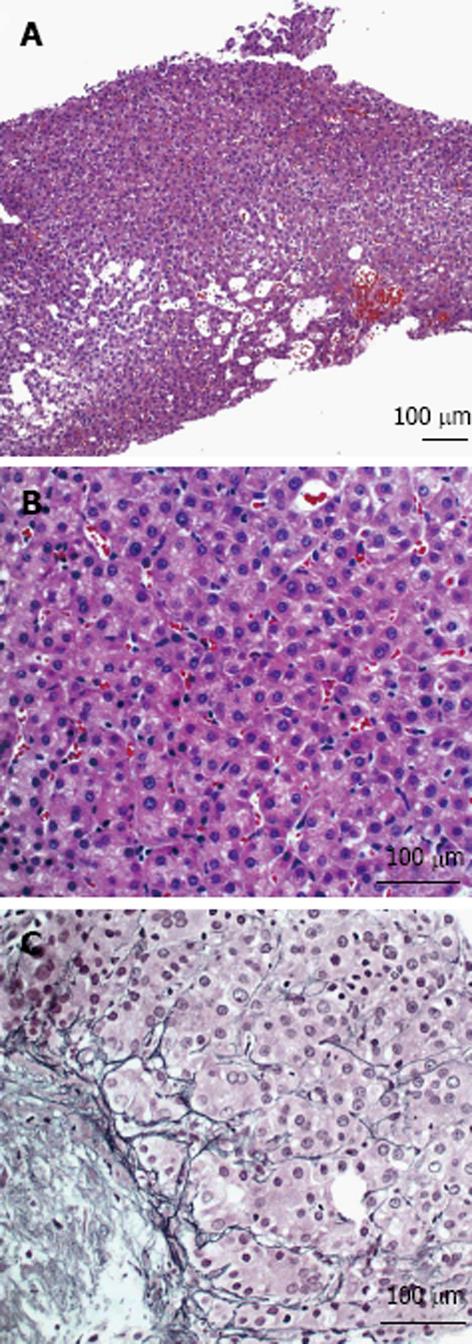

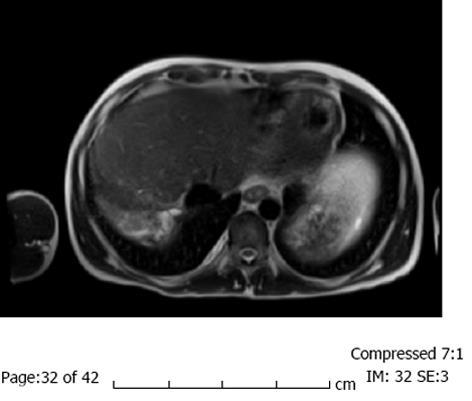

A 29-year-old male with a history of biliary atresia with failed Kasai procedure complicated with progressive cirrhosis and portal hypertension that received a left lateral segment living donor liver transplant (LDLT) from his biological father at 15 years of age. His immunosuppressive regimen included tacrolimus, and sirolimus. Eleven years after his LDLT, he developed advanced liver fibrosis and portal hypertension that manifested as refractory ascites. He received a splenectomy and a central spleno-renal shunt that eventually failed. He then underwent a side-to-side porto-caval shunt (PCS) at age 27 years. After 2 years with controlled disease, he presented with recurrent ascites and overt hepatic encephalopathy (HE) related to his progressive graft failure. His clinical course was also complicated by severe protein losing enteropathy due to his worsening portal hypertension (sprue was excluded by small bowel biopsy). Other causes of hypoalbuminemia were ruled out (e.g., kidney injury secondary sirolimus, as evidenced by 24-h urine collection with minimal protein and normal creatinine). Liver biopsy at this time showed stage 3-4 fibrosis. In addition, there was a paucity of interlobular bile ducts with degenerative changes in the remaining ducts, features compatible with chronic allograft rejection. A few months after, an abdominal ultrasound of the graft revealed a hepatic mass measuring 2.9 cm × 2.2 cm located in segment 2/3 and no evidence of intrahepatic duct dilation. Dynamic CT imaging showed a 3 cm lesion in the left lateral segment that was slightly hypodense and indeterminate in nature (Figure 1). A dynamic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) using liver mass protocol was performed due to the indeterminate nature of the lesion on CT and demonstrated increased vascularity of the lesion, raising suspicion for HCC. An ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsy of the mass revealed a well-differentiated HCC (Figure 2). Chest CT scan and bone scan demonstrated no evidence of extra hepatic disease. Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level was slightly elevated at 17 ng/mL (normal < 6 ng/mL). Anti-HBcAb (anti-hepatitis B core total antibodies) at this time and a year before showed negative results. The lesion was subsequently treated by percutaneous microwave ablation (PMWA).

Follow up MRI was performed 1.5 mo after the ablation and showed no residual tumor (Figure 3). The patient was subsequently listed for repeat liver transplantation. However, while on the wait-list he developed a second post-transplant malignancy, an EBV negative Burkitt’s type lymphoma. He received chemotherapy for the lymphoma but succumbed to complications due to the treatment that was in part limited by his advanced liver disease.

Liver transplantation provides the highest survival rates among patients with decompensated cirrhosis and complications of portal hypertension but recipients have a 2-4 fold increased risk of developing de-novo malignancies when compared to matched healthy controls[16]. De-novo malignancies represent 30% of post-transplant deaths and one of the most common causes of death in patients that survive beyond a year after transplantation[3,17]. Although there is an increased risk of developing malignancies, De-novo HCC is uncommon[3,17].

When HCC after transplantation is identified, it is crucial to know if it is a recurrent malignancy as this carries a poor prognosis. Travesani et al[17] have proposed an algorithm where they suggest suspicion primary features of a recurrent case including lymph node invasion, macro and microvascular invasion, tumor size > 5 cm, high grade tumor, bi-lobar involvement and high alpha fetoprotein levels. Secondary features include early occurrence, < 2 years, and extra hepatic localization. Without the presence of these characteristics, the suspicion turns towards a de-novo HCC. Other common clinical factors that suggest a de-novo case, even in patients transplanted for or with a previous HCC, are older donor age, alcoholic liver disease, viral hepatitis, recurrent liver disease and exposure to environmental carcinogens. Although the clinical features cannot guarantee the distinction with certainty, molecular techniques may permit differentiation of donor from recipient origin[17]. In addition, allografts have a certain degree of hepatocyte chimerism (graft and recipient cells) that also correlates with the degree of hepatic injury and is strongly associated with hepatitis[18].

The pathogenesis of HCC appears to be related to chronic hepatic inflammation that eventually leads to fibrosis and cirrhosis. The inflammatory microenvironment in the liver leads to a proliferative state that can promote dysplasia and eventually malignancy regardless of the underlying liver disease[1]. Graft rejection, which is an immunological surge against detected antigens found within the graft, can generate a chronic inflammatory state[19] and create an environment that promotes oncogenesis and dysplasia. Other well-established risk factors for promoting carcinogenesis include the use of immunosuppressive therapy as it reduces immune surveillance, increased age and gender specific cancer risks, development of insulin resistance and exposure to viral infections (HBV and HCV)[3,16,17].

From the 16 cases of de-novo HCC occurrence reported so far in the literature, 14 had positive viral serology (HVB or HCV) (Table 1). In these cases the viral infection likely drove tumorogenesis. However, this is a novel case describing a de-novo HCC after a LDLT in a pediatric patient. Our case represents the development of a hepatic tumor in the setting of advanced hepatic fibrosis, likely from chronic allograft rejection, without any underlying viral disease or other chronic infection. Interestingly both biliary atresia itself and Kasai procedure have been associated with the development of HCC[20-22]. However, given the 14 year gap from transplant to development of HCC, this probably did not contribute to the development of HCC in this particular patient.

| Patient | Ref. | OLT indication | Age | Gender | Immunosuppression | Interval (yr) | Type of donor | PVS | Approach after de-novo HCC |

| 1 | Saxena et al[4] | HCV and ALD | 63 | M | CYA, AZA and Pred | 7 | DD | Yes | Retransplant |

| 2 | Levitsky et al[5] | HCV and ALD | 48 | M | CYA, AZA and Pred | 5 | N/A | Yes | NR |

| 3 | Croitoru et al[6] | HCV and NAFLD | 61 | M | CYA and Pred | 6 | DD | Yes | Retransplant |

| 4 | Flemming et al[7] | HBV | NR | M | NR | 9 | DD | Yes | Hepatic Resection |

| 5 | Flemming et al[7] | HBV | NR | M | NR | 8 | DD | Yes | Retransplant and Hepatic Resection |

| 6 | Torbenson et al[8] | HBV | 51 | M | NR | 8.5 | DD | Yes | Retransplant |

| 7 | Kita et al[9] | HBV | 43 | M | NR | 14 | NA | Yes | Retransplant |

| 8 | Yu et al[10] | HBV | 36 | M | TAC, MMF andPred | 2 | LD | Yes | RFA |

| 9 | Sotiropoulos et al[11] | Budd-Chiari Syndrome | 61 | F | NR | 22 | NA | Yes | TACE |

| 10 | Sotiropoulos et al[11] | ALD | 65 | M | NR | 5 | NA | NR | RFA |

| 11 | Vernadakis et al[12] | ALD | 59 | M | CYA, MMF and Pred | 3 | DD | No | Hepatic Resection |

| 12 | Tamè et al[13] | HCV | 54 | M | TAC and Pred | 6 | DD | Yes | TACE |

| 13 | Saab et al[14] | HCV | 47 | F | TAC and MMF | 19 | - | Yes | TACE, RFA, Sorafenib, Retransplant |

| 14 | Tamè et al[13] | SSC | 44 | M | TAC and Pred | 6 | DD | Yes | Sorafenib |

| 15 | Navarro Burgos et al[15] | HCV and HBV | 45 | M | NR | 0.75 | DD | Yes | TACE |

| 16 | The present case | Biliary atresia | 29 | M | TAC and Sirolimus | 14 | LD | No | PMWA |

Although current treatment guidelines for De-novo HCC after LT have not been well established, it was suggested that these cases be approached according to the current guidelines for primary and recurrent HCC[17]. The strategies that have been used in the reported cases to date are: re-transplantation (n = 6)[4,6-9,14], trans-arterial chemoembolization (TACE) (n = 4)[11,13-15], hepatic resection (n = 3)[7,12], radiofrequecy ablation (RFA) (n = 3)[10,11,14], medical therapy with Sorafenib (n = 2)[13,14] and PMWA in our case. Two of the reported cases used more than one procedure[7,14].

Proper age and gender appropriate cancer screening and surveillance is universally practiced among transplant recipients to diagnosis early stage malignancy. Since approximately one-fifth of all post-transplant deaths are related to de-novo neoplasms (including de-novo HCC)[3] and the incidence of HCC recurrence can be as high as 18.3% after transplant[2], many transplant programs have in place post-LT screening and surveillance for HCC in patients transplanted for HCC along with other appropriate cancer screening and surveillance[3]. However, these protocols for post-LT screening and surveillance are not uniform amongst centers as there is a general lack of evidence base for deciding on a specific protocol. This remains to be established.

In summary, we describe the first case of de-novo HCC after living donor liver transplantation in a patient with a prior history of biliary atresia who developed graft dysfunction and complications of portal hypertension. This case and the increase in reports of de-novo development of HCC in liver grafts of patients without HCC prior to LT challenges us to define the incidence of development of HCC in post-LT patients with chronic injury and graft fibrosis to determine when there is utility in recommending screening and surveillance of these individuals for HCC, and design appropriate protocols to carry this out.

A 29-year-old male with a history of biliary atresia with failed Kasai procedure complicated with progressive cirrhosis and portal hypertension that received a left lateral segment living donor liver transplant (LDLT) from his biological father at 15 years of age.

Biliary atresia, complicated with progressive cirrhosis and portal hypertension that received a left lateral segment living donor liver transplant LDLT.

A case of de-novo hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (confirmed by ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsy of the mass) 14 years after a pediatric living related donor liver transplantation for end-stage liver disease without positive hepatitis B or C viral serology.

Follow up magnetic resonance imaging was performed 1.5 mo after the ablation and showed no residual tumor.

The lesion was subsequently treated by percutaneous microwave ablation. The patient was subsequently listed for repeat liver transplantation. Current screening and treatment guidelines have not been well established.

This increasing phenomenon challenges us to define the utility of screening and surveillance for HCC in these individuals.

| 1. | Kirstein MM, Vogel A. The pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis. 2014;32:545-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Roayaie S, Schwartz JD, Sung MW, Emre SH, Miller CM, Gondolesi GE, Krieger NR, Schwartz ME. Recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplant: patterns and prognosis. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:534-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 354] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Burra P, Rodriguez-Castro KI. Neoplastic disease after liver transplantation: Focus on de novo neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:8753-8768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Saxena R, Ye MQ, Emre S, Klion F, Nalesnik MA, Thung SN. De novo hepatocellular carcinoma in a hepatic allograft with recurrent hepatitis C cirrhosis. Liver Transpl Surg. 1999;5:81-82. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Levitsky J, Faust TW, Cohen SM, Te HS. Group G streptococcal bacteremia and de novo hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Croitoru A, Schiano TD, Schwartz M, Roayaie S, Xu R, Suriawinata A, Fiel MI. De novo hepatocellular carcinoma occurring in a transplanted liver: case report and review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:1780-1782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Flemming P, Tillmann HL, Barg-Hock H, Kleeberger W, Manns MP, Klempnauer J, Kreipe HH. Donor origin of de novo hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatic allografts. Transplantation. 2003;76:1625-1627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Torbenson M, Grover D, Boitnott J, Klein A, Molmenti E. De novo hepatocellular carcinoma in a liver allograft associated with recurrent hepatitis B. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:2205-2206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kita Y, Klintmalm G, Kobayashi S, Yanaga K. Retransplantation for de novo hepatocellular carcinoma in a liver allograft with recurrent hepatitis B cirrhosis 14 years after primary liver transplantation. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:3392-3393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yu S, Guo H, Zhuang L, Yu J, Yan S, Zhang M, Wang W, Zheng S. A case report of de novo hepatocellular carcinoma after living donor liver transplantation. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sotiropoulos GC, Frilling A, Molmenti EP, Brokalaki EI, Beckebaum S, Omar OS, Broelsch CE, Malagó M. De novo hepatocellular carcinoma in recurrent liver cirrhosis after liver transplantation for benign hepatic disease: is a deceased donor re-transplantation justified? Transplantation. 2006;82:1112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Vernadakis S, Poetsch M, Weber F, Treckmann J, Mathe Z, Baba HA, Paul A, Kaiser GM. Donor origin de novo HCC in a noncirrhotic liver allograft 3 years after liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2010;23:341-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tamè M, Calvanese C, Cucchetti A, Gruppioni E, Colecchia A, Bazzoli F. The Onset of de novo Hepatocellular Carcinoma after Liver Transplantation can be both of Donor and Recipient origin. A Case Report. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2015;24:387-389. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Saab S, Zhou K, Chang EK, Busuttil RW. De novo Hepatocellular Carcinoma after Liver Transplantation. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2015;3:284-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Navarro Burgos JB, Lee KW, Shin YC, Lee DS, Lee KB, Yi NJ, Suh KS. Inexplicable Outcome of Early Appearance of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the Allograft After Deceased Donor Liver Transplantation: A Case Report. Transplant Proc. 2015;47:3012-3015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rodríguez-Perálvarez M, De la Mata M, Burroughs AK. Liver transplantation: immunosuppression and oncology. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2014;19:253-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Trevisani F, Garuti F, Cucchetti A, Lenzi B, Bernardi M. De novo hepatocellular carcinoma of liver allograft: a neglected issue. Cancer Lett. 2015;357:47-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kleeberger W, Rothämel T, Glöckner S, Flemming P, Lehmann U, Kreipe H. High frequency of epithelial chimerism in liver transplants demonstrated by microdissection and STR-analysis. Hepatology. 2002;35:110-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Neil DA, Hübscher SG. Current views on rejection pathology in liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2010;23:971-983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Brunati A, Feruzi Z, Sokal E, Smets F, Fervaille C, Gosseye S, Clapuyt P, de Ville de Goyet J, Reding R. Early occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in biliary atresia treated by liver transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2007;11:117-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Iida T, Zendejas IR, Kayler LK, Magliocca JF, Kim RD, Hemming AW, Gonzalez-Peralta RP, Fujita S. Hepatocellular carcinoma in a 10-month-old biliary atresia child. Pediatr Transplant. 2009;13:1048-1049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hol L, van den Bos IC, Hussain SM, Zondervan PE, de Man RA. Hepatocellular carcinoma complicating biliary atresia after Kasai portoenterostomy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:227-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chok KSH, Coelho JCU S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH