Published online Oct 18, 2017. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v9.i29.1158

Peer-review started: March 17, 2017

First decision: May 2, 2017

Revised: July 19, 2017

Accepted: September 3, 2017

Article in press: September 5, 2017

Published online: October 18, 2017

Processing time: 220 Days and 2.7 Hours

Extra-hepatic spread is present in 5% to 15% of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) at the time of diagnosis. The most frequent sites are lung and regional lymph nodes. Here, we report 3 cases of unsuspected HCC with symptoms due to bone lesions as initial presentation. Morphological characteristics and immunohistochemistry from the examined bone were the key data for diagnosis. None of the patients had an already known chronic liver disease. Differential diagnoses with HCC upon ectopic liver disease or hepatoid adenocarcinoma were shown. Therapy with the orally active multikinase inhibitor sorafenib plus symptomatic treatment was indicated.

Core tip: Metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma should be included within the differential diagnoses of bone metastases of unknown origin, even in the absence of already known chronic liver disease.

- Citation: Monteserin L, Mesa A, Fernandez-Garcia MS, Gadanon-Garcia A, Rodriguez M, Varela M. Bone metastases as initial presentation of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol 2017; 9(29): 1158-1165

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v9/i29/1158.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v9.i29.1158

Screening programs for early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) have been shown to be cost-effective and to improve survival[1]. However, there are a proportion of patients who develop HCC in the presence of an unknown primary chronic liver disease that is diagnosed at the time of first decompensation, generally ascites. In addition, incidence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is increasing; it has been shown that these patients develop HCC before cirrhosis was established and, generally, that they are diagnosed out of surveillance as well. In these two last situations, patients can present with extra-hepatic disease and fewer options of effective therapy to prolong survival. We report, herein, 3 cases of HCC that debuted as metastatic bone lesions.

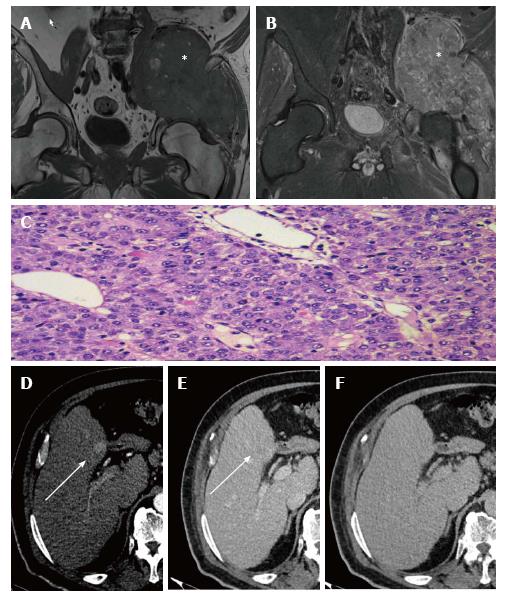

A 64-year-old male, current smoker (20 cigarettes daily) and drinker (20 g alcohol daily), presented with pain in the lower right limb that had begun several months previous. Initially, the pain was attributed to lumbar degenerative pathology in the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae. A multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) scan of thorax-abdomen-pelvis with intravenous and oral contrast showed a large, solid, contrast-enhanced mass affecting psoas, iliac and gluteus minor muscles with iliac bone infiltration. This great lytic lesion affected the iliac paddle wall, thinning the acetabular roof. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study confirmed the destructive, heterogeneous and highly vascularized tumor (Figure 1A and B), resembling an osteochondroma.

Histologically, a solid neoformation formed by cells of epithelioid habit that showed large eosinophilous cytoplasm compartments and irregular, vesiculous nuclei with patent nucleolus and frequent figures of mitosis was observed, accompanied by a rich vascular network adjacent to a soft tissue. Tumor cells were strongly positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, cytokeratin 8 and hepatocytes. Cytokeratin 20, 7, 19 and EMA were completely negative. This was conclusive for HCC. A second biopsy performed later over the same site, just if a mistake had been made in the processing or identification of tissue, showed the presence of a proliferation, composed of cells that mimic hepatocytes, with marked incipient anisopleomorphism, extended in sheets and infiltrating different soft tissues. Immunohistochemical staining was performed, showing hepatocyte, cytokeratin AE 1 and AE 3 positivity; the rest of the requested immunohistochemical tests (alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), prostate antigen) were negative again. Therefore, metastasis from a well-differentiated HCC (Figure 1C) was confirmed.

Tests of peripheral blood showed AFP level of 3.4 ng/mL (upper normal value 8 ng/mL), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 133 U/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) of 35 U/L, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) of 161 U/L, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) of 95 U/L and bilirubin of 1 mg/dL. Liver stiffness measurement value was 12.5 kPa, suggestive of significant fibrosis. Upper endoscopy revealed no signs of portal hypertension. Hepatitis B and C chronic infection were excluded.

Multiphasic hepatic TCMD depicted a 24-mm, ill-defined area that enhanced in the arterial phase, with washout in delayed phases, in segment IV that was associated with vascular invasion of the left portal vein and with left lobe hypertrophy in a polylobed liver (Figure 1D-F). This imaging impressed the finding of tumor injury meeting non-invasive diagnosis criteria for HCC. Taking into account the symptoms, defined as ECOG PS 2[2], and the results of biopsies and radiological staging, BCLC-C hepatocellular carcinoma was diagnosed.

Treatment with analgesics plus external palliative radiotherapy in the pelvic area was initiated. Once the patient’s pain and discomfort were alleviated, sorafenib was started at October 11, 2014. Clinical evolution was good, with progressive recovery of general status to ECOG PS 0 together with radiological regression of intra- and extra-hepatic disease. The bone metastases at initial scan (July 21, 2014) measured 47 mm × 132 mm × 181 mm, and measurement of the same lesion at the last study (September 15, 2016) showed it to be 40 mm × 80 mm × 80 mm.

The patient has been taking sorafenib up to the writing of this report, with minor adverse events at full dose. He has been able to stop morphine-derived and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Due to excellent tolerance to sorafenib, in case of radiological progression, the patient will be assessed to switch to regorafenib.

This is a 66-year-old male, former drinker of 80 g alcohol daily, with chronic hepatitis C virus infection, secondary iron overload, porphyria cutanea tarda, arterial hypertension and obesity. He frequented Traumatology and Emergency Departments due to left inguinal mechanical pain that distally radiated through the left leg since August of 2011. He presented with spontaneous fracture of the left hip (October 16, 2012) that needed a total hip prosthesis placement (October 22, 2012). Examination of the surgical specimen determined a bone metastasis of undifferentiated carcinoma.

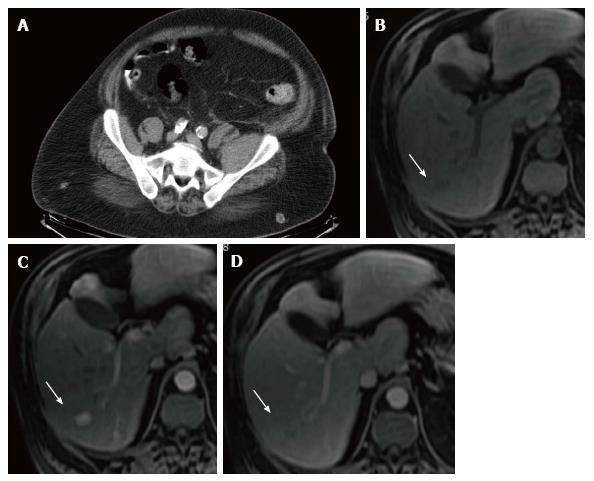

A thorax-abdomen-pelvis MDCT was performed to find the primary tumor. An ill-defined hypodense nodule of less than 1 cm in the right hepatic lobe that cannot be assessed due to its size was seen, together with a small peripancreatic adenopathy and a left femoral neck fracture that did not present sclerotic borders, and represented the location where a hypodense lytic lesion was observed (Figure 2A). A multiphasic liver TCMD informed of normal liver size and morphology.

Upper endoscopy revealed erosive gastritis without esophageal varices. Laboratory values were AFP of 4.2 ng/mL, AST of 227 U/L, ALT of 181 U/L, ALP of 311 U/L, GGT of 629 U/L and bilirubin of 1 mg/dL. A dynamic hepatic MRI was performed and showed multiple small focal lesions, tenuously hypointense in T1 and hyperintense in T2, with intense contrast uptake in the arterial phase and washout in the portal phase in the larger ones (Figure 2B-D). An ultrasonographic-guided biopsy-trucut with an 18-gauge needle was taken over one of the larger liver lesions, and demonstrated a well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma, thus identifying the primary focus.

The patient was finally diagnosed with advanced ECOG PS 0 BCLC-C HCC and sorafenib was started on December 18, 2012. Due to radiological progression, he was assessed for second-line clinical trials (February, 2014) but ultimately died due to tumor progression on January 20, 2015.

This is a 74-year-old diabetic man, who is a current drinker (40 g alcohol daily) and occasional smoker. In January 2014, he complained of pain in the upper hemiabdomen and pain in the lumbosacral region which radiated to the lateral face of the right thigh. He also presented functional impotence of the right lower limb and dysesthesia. No anorexia, asthenia nor weight lose were present. He was ECOG PS 2.

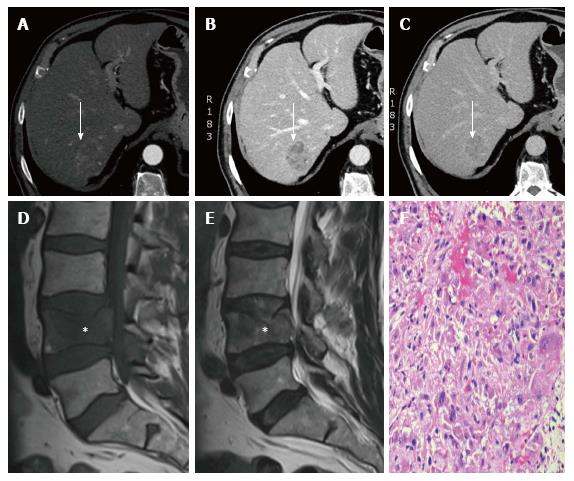

Blood count, biochemistry, including liver function tests and AFP, were mostly within the normal range (AFP of 4.2 ng/mL, AST of 128 U/L, ALT of 93 U/L, ALP of 192 U/L, GGT of 459 U/L and bilirubin of 1 mg/dL). Abdominal ultrasound detected a 15-mm hypoecogenic liver focal lesion in the left lobe. The study was completed with a multiphasic abdomen-pelvis MDCT with the finding of a 40 mm × 39 mm focal liver lesion in the right lobe that could correspond with metastases (Figure 3A-C). A pathological fracture with significant stenosis of the central spinal channel provoking compromise of neurological structures was detected in the body of the fourth lumbar vertebrae. Lumbar MRI confirmed this lesion and another very similar one in the second lumbar vertebrae (Figure 3D and E).

The Neurosurgery Team performed a cementation of the fourth lumbar vertebra after an intraoperative biopsy at 14-AUG-2014. The pathological description was compatible with a metastatic focus of HCC, with the following immunophenotypic profile: Cytokeratin AE1/AE3, cytokeratin 8, CD138 and TTF1 positivity, but hepatocyte, cytokeratin 7, CDX, synaptophysin, S100, P40 and P53 negativity (Figure 3F). This patient also presented with several very painful lesions in the dorsal spine.

The patient was administered intrathecal perfusion of fentanyl, intravenous zoledronic bolus and external radiotherapy (total dose of 20 Gy) to ameliorate symptoms. In spite of all efforts, his quality of life was poor and he worsened very fast. He was so fragile that he was not a candidate for sorafenib drug therapy and home-based palliative care provided support during the last 5 mo of his life. He finally deceased on October 26, 2015.

HCC is the most common primary tumor in the liver, with the fifth in incidence in men worldwide and occupying the second place in mortality attributed to cancer[3]. It develops mainly in the context of chronic liver disease, especially secondary to chronic infection by hepatitis B and C. Patients who develop HCC generally do not present symptoms; however, it should be suspected in those cases with previously compensated cirrhosis that are complicated by clinical decompensation. Extra-hepatic disease is more frequent in advanced tumors (greater than 5 cm, multifocal, with vascular invasion or cancer-related symptoms). Initial manifestation of unsuspected HCC as a bone metastasis is rare according to literature[4-17]. In our referral unit, this is the first sign of unknown HCC in less than 0.9% of incident cases. These cases are usually located in the vertebrae, pelvis, ribs and skull, as shown in Table 1.

| Ref. | Year | n | Location | Survival1 |

| Nowak et al[4] | 1983 | 1 | Rib | NR |

| Fueyo Margareto et al[5] | 1986 | 1 | Multiples bones | NR |

| Raoul et al[6] | 1995 | 3 | Skull | 27 mo (alive) |

| Iliac bone | 31 mo (alive) | |||

| Femur | 31 mo (dead)2 | |||

| Horita et al[7] | 1996 | 1 | Breastbone | 9 mo (alive)2 |

| Iosca et al[8] | 1998 | 1 | Left iliac bone | > 45 mo (alive)2 |

| Soto et al[9] | 2000 | 1 | Rib | 28 mo (alive) |

| Hofmann et al[10] | 2003 | 1 | Chest wall | 12 mo (alive)2 |

| Qureshi et al[11] | 2005 | 1 | Chest wall | NR |

| Hyun et al[12] | 2006 | 1 | Rib and third thoracic vertebrae | 12 mo (alive)2 |

| Rastogi et al[13] | 2013 | 1 | Scapula and occipital bone | 2 mo (alive)2 |

| Ruiz-Morales et al[14] | 2014 | 2 | Vertebrae, ribs, sacrum, scapula | NR |

| Cervical vertebrae, right shoulder | NR | |||

| Hwang et al[15] | 2015 | 1 | Vertebral body and iliac bone | 8 mo (alive) |

| Subasinghe et al[16] | 2015 | 1 | Occipital bone | NR |

| Alauddin et al[17] | 2016 | 1 | Left anterior chest wall | NR |

| Monteserín | 2017 | 3 | Iliac bone | 42 mo (alive) |

| Femur | 41 mo (dead) | |||

| Vertebral bodies | 20 mo (dead) |

In the 3 cases described herein, we have detected both intra- and extra-hepatic disease at once, but sometimes an extra-hepatic HCC without a primary intra-hepatic HCC can be seen. This last situation can be explained in different ways.

The first is ectopic liver carcinogenesis[18]. Characteristically, the pathologic examination of HCC arising from ectopic liver reveals normal liver tissue, including portal triads. It may be connected to the liver by a fibrous stalk, which is composed of the portal vein, hepatic artery or bile duct. If no evidence of primary cancer of the liver is present after a long-term follow-up with various specific liver imaging studies, a malignancy originating from ectopic liver should be suspected. This is a very rare entity with few cases described in literature, but normally a chronic liver disease or cirrhosis is present in the mother liver.

The second possibility is the presence of a hepatoid adenocarcinoma (HAC)[19]. This is a variant form of adenocarcinoma, characterized by vast hepatic differentiation. It generally arises in older patients, produces AFP and originates from the endoderm. The most common primary origin is the gastrointestinal tract and lung. There are some cases of HAC with liver metastases that mimic HCC with extra-hepatic spread. Differential diagnoses between both entities can be facilitated by immunohistochemistry. HAC usually is Hep-Par1-negative, cytokeratin 7-negative, cytokeratin-positive and cytokeratin 19-positive; and, it commonly displays two properties: Canalicular pattern of polyclonal CEA staining and expression of albumin messenger RNA as detected by in situ hybridization. The preferred occurrence in the stomach may be explained by the fact that liver and stomach share a common embryologic origin from the primitive foregut.

The third possibility is the presence of a variant of extra-hepatic germ cell tumor, arising either in the ovary or mediastinum, with morphologic as well as immunophenotypic features highly characteristic of HCC. For the most part, the majority of such tumors appear to represent yolk sac tumors with hepatoid differentiation (hepatoid yolk sac tumors), positive for SALL4, glypican 3, and AFP[20,21].

The last possibility, which is very uncommon, is the hazard of metastatic HCC without an intra-hepatic mass due to spontaneous regression of primary HCC in the liver[22].

Metastatic bone lesions of HCC often cause local pain, neurological manifestations, palpable subcutaneous masses and pathological fractures. In the search of the primary tumor, abdominal MDCT can sometimes show a liver with normal morphology and without focal lesions, as in cases 1 and 2, making diagnosis difficult and being necessary to complete the study with contrast-enhanced hepatic MRI, especially in situations of high clinical suspicion. In our cases, the morphology and immunohistochemistry of the bone material were the key data for getting the final diagnosis.

Systemic palliative treatment with sorafenib should be considered at the first line in advanced HCC according to the guidelines[1]. The objectives of concomitant treatment are improvement of pain, preservation of functions and maintenance of bone integrity. Multidisciplinary teams play an essential role in the care of these patients, offering multimodal therapy. In localized lesions, external radiotherapy relieves the pain in 60%-80% of cases, with a complete response described between 15% and 58%[23]. The third patient received additional treatment with intravenous zoledronic acid, which acts by inhibiting osteoclasts and is very efficacious in the case of bone metastases of other tumors, such as prostate or breast[24], contributing to an improvement in the quality of life due to decreased pain. Before starting treatment with zoledronic acid, the levels of hypocalcaemia and vitamin D should be corrected, with a subsequent monitoring of renal function and maintenance of good hydration.

These 3 cases illustrate the spectrum of the metastatic bone HCC debut. Case 1 was treated with local and systemic therapy, and he continues to be alive with minor symptoms. Case 2 presented a regular evolution with shorter survival. Case 3 was too symptomatic from the beginning and he only received supportive care.

Sorafenib has dramatically changed the prognosis of advanced HCC. In the SHARP trial population, the median overall survival was 10.7 mo[25]. Cases 1 and 2 have been taken sorafenib over 26 and 13 consecutive mo respectively, with 26 and 25 mo of survival, in that order. Recently, it has been communicated that the type of radiological progression to sorafenib is an important prognostic factor of postprogression survival[26]. Indeed, postprogression survival is shorter when a new extra-hepatic lesion appears, in comparison with survival after growth of a pre-existing intra-hepatic lesion. This information should be used to switch patients to regorafenib or to second-line trials[27].

To conclude, the appearance of a neurological complaint, such as low back pain or root or motor deficit (regardless of the neurological pathology derived from enolic polyneuropathy, which is so common in these patients), cannot be ignored, because this is sometimes the first manifestation of a metastatic HCC.

The 3 middle-aged male patients presented with dissimilar symptoms. Case 1 presented with lower right limb pain from several months. Case 2 presented with left inguinal pain and hip fracture. Case 3 presented with abdominal and lumbosacral pain, together with dysesthesia at right thigh.

The physical signs of the 3 cases were also dissimilar. Upon physical examination, case 1 presented total functional impotence of the right lower limb. Case 2 had left inguinal mechanical pain distally radiating through the left leg to the knee. Case 3 presented mild abdominal tenderness plus limitation of flexion of dorsolumbar spine.

Malignant tumors: Osteochondroma, soft tissue sarcomas, carcinoma of unknown origin and metastatic tumors.

Case 1 had no remarkable findings for the laboratory tests, except mild elevation of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP). Case 2 presented higher levels of AST, alanine aminotransferase, ALP and gamma-glutamyl peptidase (GGT), probably related to underlying chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Case 3 presented with mild elevation in AST and GGT. It is remarkable than in all 3 cases AFP remained within normal values.

For all these cases, computed tomography scan and dynamic magnetic resonance showed the primary tumor located in the liver together with the extra-hepatic lesions. It is important to say that in the first case the liver cancer had gone unnoticed by the MDCT scan of thorax-abdomen-pelvis with intravenous and oral contrast. It was only detected with a specific multiphasic hepatic TCMD.

For the 3 cases, histological examination of bone lesions showed a solid neoformation formed by cells of epithelioid habit with large cytoplasmic compartment and irregular, vesiculous nuclei with patent nucleolus and frequent figures of mitosis, accompanied by a rich vascular network adjacent to a soft tissue. In all 3 cases, tumor cells were strongly positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and cytokeratin 8 and negative for cytokeratin 7.

All 3 patients received different therapies for pain relief (oral and intravenous analgesics, bisphosphonates, external radiotherapy). In addition, case 2 received a total hip replacement and case 3 received cementation of the fourth lumbar vertebra. Cases 1 and 2 received sorafenib for more than 12 mo as specific therapy for advance hepatocellular carcinoma.

Very few cases of metastatic bone presentation of hepatocellular carcinoma have been reported in the literature. The clinical and therapeutic management of these patients is a challenge and several combined therapies can be applied to obtain long survivals with acceptable quality of life.

Multimodal therapy is referred to the combination of local and systemic treatments to relieve symptoms secondary to bone destruction due to metastases of hepatocellular carcinoma. It includes sorafenib but also external radiotherapy, cementation of selected vertebrae, intravenous bisphosphonates, etc.

Metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma should be included within the differential diagnoses of bone metastases of unknown origin, even in the absence of already known chronic liver disease. With proper symptomatic and systemic therapies these patients can have a longer survival with preserved quality of life.

The authors have described 3 cases of bone metastases as initial presentation of hepatocellular carcinoma. It is an interesting contribution to the literature on hepatocellular carcinoma and its metastasis.

The authors thank the patients and their relatives for their kind permission to use their medical findings in this report.

| 1. | European association for the study of the liver; European Organisation For Research And Treatment Of Cancer. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4059] [Cited by in RCA: 4561] [Article Influence: 325.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, Carbone PP. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7038] [Cited by in RCA: 8236] [Article Influence: 191.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359-E386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20108] [Cited by in RCA: 20711] [Article Influence: 1882.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (23)] |

| 4. | Nowak MM, Ponsky JL. Hepatocellular carcinoma metastatic to rib: an approach to an unusual chest wall tumor. J Surg Oncol. 1983;24:196-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fueyo Margareto J, Llach Vila J, Valderrama Labarca R, Pérez Ayuso R. [Bone metastases as the initial manifestation of hepatocarcinoma]. Rev Esp Enferm Apar Dig. 1986;70:570-571. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Raoul JL, Le Simple T, Le Prisé E, Meunier B, Ben Hassel M, Bretagne JF. Bone metastasis revealing hepatocellular carcinoma: a report of three cases with a long clinical course. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1162-1164. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Horita K, Okazaki Y, Haraguchi A, Natsuaki M, Itoh T. [A case of solitary sternal metastasis from unknown primary hepatocellular carcinoma]. Nihon Kyobu Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1996;44:959-964. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Iosca A, Spaggiari L, Salcuni P. A bone hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis without hepatic tumor: a long-term follow-up. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Soto S, Artaza T, Gomez R, Camacho FI, Rodriguez I, Gonzalez C, Potenciano JL, Rodriguez R. Rib metastasis revealing hepatocellular carcinoma. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:333-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hofmann HS, Spillner J, Hammer A, Diez C. A solitary chest wall metastasis from unknown primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:557-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Qureshi SS, Shrikhande SV, Borges AM, Shukla PJ. Chest wall metastases from unknown primary hepatocellular carcinoma. J Postgrad Med. 2005;51:41-42. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Hyun YS, Choi HS, Bae JH, Jun DW, Lee HL, Lee OY, Yoon BC, Lee MH, Lee DH, Kee CS. Chest wall metastasis from unknown primary site of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2139-2142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rastogi A, Bihari C, Jain D, Gupta NL, Sarin SK. Hepatocellular carcinoma presenting with multiple bone and soft tissue metastases and atypical cytomorphological features--a rare case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2013;41:640-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ruiz-Morales JM, Dorantes-Heredia R, Chable-Montero F, Vazquez-Manjarrez S, Méndez-Sánchez N, Motola-Kuba D. Bone metastases as the initial presentation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Two case reports and a literature review. Ann Hepatol. 2014;13:838-842. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Hwang SW, Lee JE, Lee JM, Hong SH, Lee MA, Chun HG, Chun HJ, Lee SH, Jung ES. Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Cervical Spine and Pelvic Bone Metastases Presenting as Unknown Primary Neoplasm. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2015;66:50-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Subasinghe D, Keppetiyagama CT, Sudasinghe H, Wadanamby S, Perera N, Sivaganesh S. Solitary scalp metastasis - a rare presentation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2015;9:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Alauddin Z, Shahid A, Fatima N, Masood M, Qureshi A, Mirza ZR. Unusual Presentation of Bone Metastasis from Hepatocellular Carcinoma Mimicking as Breast Lump. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2016;26:710-711. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Arakawa M, Kimura Y, Sakata K, Kubo Y, Fukushima T, Okuda K. Propensity of ectopic liver to hepatocarcinogenesis: case reports and a review of the literature. Hepatology. 1999;29:57-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Terracciano LM, Glatz K, Mhawech P, Vasei M, Lehmann FS, Vecchione R, Tornillo L. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma with liver metastasis mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma: an immunohistochemical and molecular study of eight cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:1302-1312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Prat J, Bhan AK, Dickersin GR, Robboy SJ, Scully RE. Hepatoid yolk sac tumor of the ovary (endodermal sinus tumor with hepatoid differentiation): a light microscopic, ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study of seven cases. Cancer. 1982;50:2355-2368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ulbright TM. Gonadoblastoma and hepatoid and endometrioid-like yolk sac tumor: an update. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2014;33:365-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Clos A, Hernández A, Sánchez MD, Tenesa M, Julián JF, Armengol C, Sala M. Spontaneous regression of hepatocellular carcinoma. A case report. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:286-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lutz S, Berk L, Chang E, Chow E, Hahn C, Hoskin P, Howell D, Konski A, Kachnic L, Lo S, Sahgal A, Silverman L, von Gunten C, Mendel E, Vassil A, Bruner DW, Hartsell W; American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO). Palliative radiotherapy for bone metastases: an ASTRO evidence-based guideline. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79:965-976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 597] [Cited by in RCA: 574] [Article Influence: 38.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hatoum HT, Lin SJ, Smith MR, Barghout V, Lipton A. Zoledronic acid and skeletal complications in patients with solid tumors and bone metastases: analysis of a national medical claims database. Cancer. 2008;113:1438-1445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul JL, Forner A. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9016] [Cited by in RCA: 10510] [Article Influence: 583.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 26. | Reig M, Rimola J, Torres F, Darnell A, Rodriguez-Lope C, Forner A, Llarch N, Ríos J, Ayuso C, Bruix J. Postprogression survival of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: rationale for second-line trial design. Hepatology. 2013;58:2023-2031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, Granito A, Huang YH, Bodoky G, Pracht M, Yokosuka O, Rosmorduc O, Breder V. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:56-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2160] [Cited by in RCA: 2828] [Article Influence: 314.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Spain

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chiu KW, Sazci A S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Lu YJ