Published online Sep 28, 2017. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v9.i27.1125

Peer-review started: February 7, 2017

First decision: April 1, 2017

Revised: July 20, 2017

Accepted: September 5, 2017

Article in press: September 5, 2017

Published online: September 28, 2017

Processing time: 241 Days and 6.8 Hours

To prospectively evaluate the performance of Doppler-ultrasonography (US) for the detection of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) dysfunction within a multicenter cohort of cirrhotic patients.

This study was conducted in 10 french teaching hospitals. After TIPS insertion, angiography and liver Doppler-US were carried out every six months to detect dysfunction (defined by a portosystemic gradient ≥ 12 mmHg and/or a stent stenosis ≥ 50%). The association between ultrasonographic signs and dysfunction was studied by logistic random-effects models, and the diagnostic performance of each Doppler criterion was estimated by the bootstrap method. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Tours.

Two hundred and eighteen pairs of examinations performed on 87 cirrhotic patients were analyzed. Variables significantly associated with dysfunction were: The speed of flow in the portal vein (P = 0.008), the reversal of flow in the right (P = 0.038) and left (P = 0.049) portal branch, the loss of modulation of portal flow by the right atrium (P = 0.0005), ascites (P = 0.001) and the overall impression of the operator (P = 0.0001). The diagnostic performances of these variables were low; sensitivity was < 58% and negative predictive value was < 73%. Therefore, dysfunction cannot be ruled out from Doppler-US.

The performance of Doppler-US for the detection of TIPS dysfunction is poor compared to angiography. New tools are needed to improve diagnosis of TIPS dysfunction.

Core tip: This large multicentric prospective study evaluates the performance of Doppler-ultrasonography (US) for the detection of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt dysfunction within a cohort of cirrhotic patients. Although many Doppler-US variables were significantly associated with dysfunction, the diagnostic performances of these variables were low compared to angiography.

- Citation: Nicolas C, Le Gouge A, d’Alteroche L, Ayoub J, Georgescu M, Vidal V, Castaing D, Cercueil JP, Chevallier P, Roumy J, Trillaud H, Boyer L, Le Pennec V, Perret C, Giraudeau B, Perarnau JM, STIC-TIPS group. Evaluation of Doppler-ultrasonography in the diagnosis of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt dysfunction: A prospective study. World J Hepatol 2017; 9(27): 1125-1132

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v9/i27/1125.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v9.i27.1125

Transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt (TIPS) is now routinely used for the treatment of complications of portal hypertension[1-4]. One of the main disadvantages of this technique is the frequent occurrence of stent dysfunction. Indeed, with bare-stents, a reintervention is necessary in more than half of the cases at 1 year[5-8]. Thus, strict and scheduled monitoring to search for dysfunction is usually recommended. However, the use of polytetrafluoroethylene covered stents (e-PTFE) since 2000 has improved shunt patency[9-13]. Nevertheless, shunt dysfunction can still arise in more than 25% of cases after one year with covered stents[13].

Portography to measure portal pressure gradient is the gold-standard for the detection of TIPS dysfunction[5]; however, it is an invasive procedure which cannot be conducted routinely. Doppler ultrasonography (Doppler-US) has been proposed as an alternative to angiography. Many studies have tried to define valid criteria for shunt dysfunction[8,12,14-17] but sensitivity and specificity are very different from one study to another. Among these criteria, the velocity of the portal flow, the direction of the intrahepatic portal flow and the velocity of the flow in the shunt were the most studied, but no threshold was defined. Given the inter-individual variability of portal velocity, some authors preferred an individual criterion such as the decrease of baseline value[17]. An association of many criteria may also be more relevant[14-18] but none has been properly validated so far.

The aim of our study was to evaluate prospectively the performance of Doppler-US for the detection of shunt dysfunction assessed by portography, in a multicentric cohort of cirrhotic patients.

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Tours and each patient gave written consent. This study was funded by the French Ministry of Health and by the Société Nationale Française de Gastroentérologie. This study has been registered on Clinical Trials.com under # 00593528.

This is an ancillary study from a randomized trial comparing covered and bare stents[13]. Patients were prospectively included in the cohort between February 2008 and July 2009. Cirrhotic patients who needed a TIPS for refractory ascites, hydrothorax or to prevent variceal rebleeding and were treated in 10 French tertiary teaching hospitals were included. The inclusion criteria were: (1) age between 18 and 75 years; (2) cirrhosis previously documented on histological or typical clinical signs; (3) Child-Pugh score < C12 at inclusion; (4) affiliation to the social security system; and (5) provision of informed consent to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were total portal thrombosis, known hepatocellular carcinoma, cardiac failure, pulmonary hypertension (MAP > 40 mmHg), hepatic polycystosis, dilatation of intrahepatic bile ducts, history of recurrent spontaneous hepatic encephalopathy (HE), hepatic arterial insufficiency, pregnancy, breastfeeding, inadequate contraception for patients of childbearing age.

The TIPS procedure was performed with covered or bare stent randomly assigned.

Protocol: For each patient, a Doppler-US was performed by a radiologist working in the center which included the patient. Doppler-US was carried out before the TIPS procedure, during the days following TIPS insertion, at 1 mo, and every 3 mo thereafter up to 2 years. During this follow-up, portography with portosystemic pressure gradient measurements was scheduled every six months and was performed if dysfunction was suspected from clinical signs or ultrasound. Only Doppler-US performed the day of portography, or during the 15 d before, were compared with portography in this study.

Dysfunction: Shunt dysfunction was defined as an increase of portosystemic gradient ≥ 12 mmHg and/or a stent stenosis ≥ 50% of the lumen, during angiography. Cases of shunt stenosis without portal hypertension were examined by two independent radiologists. These radiologists were not aware of the Doppler-US results and had no practice at all with vascular stents.

Doppler-US variables: Different Doppler-US variables were collected for each patient, every three months, by the same operator, on the same ultrasound unit. Patients were fasted for four hours at the time of examination: (1) flow velocity in the main portal vein and within the stent. Patients were asked to have a quiet and regular respiration, and velocities were recorded during a blockpnea. Reported result was the mean of three measurements (cm/s); (2) direction of blood flow in the intrahepatic portal vein branches. The flow was characterized as hepatopetal or hepatofugal in the left branch and the right branch; (3) portal flow modulation induced by the right atrium. The phasicity of portal blood flow was recorded and was classified as demodulated when absent vs modulated; (4) stent filling in color Doppler. The wall to wall color flow within the stent was classified as incomplete vs complete; (5) presence of ascites. Ascites was quantified as absent or moderate (peritoneal effusion in the pouch of Douglas and/or in perihepatic area) vs severe (peritoneal effusion in the abdominal cavity); (6) the relative change of the flow velocity in the main portal vein. The portal velocity was compared to the one measured at one month (considered as the baseline value). Indeed, at one month after TIPS insertion, hemodynamic disturbances are stabililized and neointimal hyperplasia within the stent is not yet significant; and (7) the conclusion of the operator. The conclusion of the physician performing the examination was also recorded (suspected dysfunction; yes or no).

Blinding: The Doppler-US examination was performed before the portography; therefore, it could not be influenced by it. Furthermore, angiography and Doppler-US were performed by different operators and the operator who performed angiography was unaware of the results of Doppler-US.

Associations between shunt dysfunction defined by angiography and Doppler-US variables were analyzed with logistic random-effects models to account for the correlation of data (each patient had several measures).

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of binary criteria were estimated by a bootstrapping method with 95%CI. This non-parametric method uses the patient as a unit of resampling, to account for the correlation of data and avoid cluster effect.

For quantitative variables (flow velocities), the areas under the curves were estimated punctually and with a bootstrapping method[19], with 95%CI.

Analyses were performed with SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, United States) and R 2.12.1 (R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing R) by a biomedical statistician.

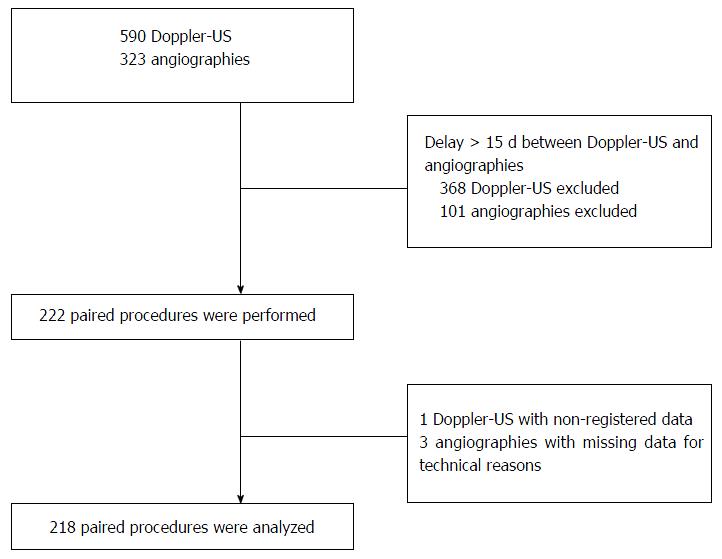

In the original study, 137 patients were included and 129 were finally analyzed[20]. Forty one patients were excluded because Doppler-US was not performed within the 15 d before portography. From these 88 patients, 222 paired Doppler-US and angiographies were selected. Some Doppler and angiography data were not registered for technical reasons. Therefore, we analyzed 218 paired Doppler-US and angiographies from 87 patients (Figure 1).

The main characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. The number of patients for each listed characteristic varies because of missing data. In our cohort, causes of cirrhosis were largely dominated by alcohol (81.6% vs 13.8% for viruses and 8% for NASH) and the patients were predominantly classified as Child B (68.8% vs 18.8% Child A and 12.5% Child C).

| Characteristic | |

| Age (yr) | 58.1 ± 7.6 |

| Male | 68 (78.2) |

| Etiology of cirrhosis | |

| Alcohol | 71 (81.6) |

| Viruses | 12 (13.8) |

| NASH | 7 (8.0) |

| Others | 2 (2.3) |

| TIPS indication | |

| Recurrent bleeding | 30 (34.5) |

| Refractory ascites | 59 (67.8) |

| Hydrothorax | 4 (4.6) |

| Child-Pugh score, n = 86 | 7.8 ± 1.6 |

| Child-Pugh score, n = 86 | |

| A | 18 (20.9) |

| B | 58 (67.4) |

| C | 10 (11.6) |

| MELD score | 11.6 ± 3.4 |

Among the 218 angiographies analyzed, 79 revealed a TIPS dysfunction in 51 patients.

Among these 79 dysfunction events, only 31 were suspected from Doppler-US, based on operator conclusions. Patency problems were detected for the first time with a median delay of 7.5 mo (6.2-18.3). The first event of dysfunction occurred in almost half of the cases (22/51) 6 ± 1 mo after TIPS insertion. Among these cases, less than half (10/22) were suspected from Doppler-US.

During portography, stenosis was located in the lower part of the stent in eight cases (20.5%), in the middle part of the stent in eight cases (20.5%), in the upper part of the stent in 16 cases (41%) and in the hepatic vein in seven cases (17.9%). Stenosis was suspected on Doppler-US in 62.5% cases (10/16) when the stenosis was located in the low or middle part of the stent, whereas it was suspected in 50% cases (8/16) when located in the upper part of the stent (Table 2).

| Dysfunction suspected (n = 21 stenosis) | Not suspected (n = 18 stenosis) | |

| Lower part of the stent | 6 (28.6) | 2 (11.1) |

| Middle part of the stent | 4 (19.1) | 4 (22.2) |

| Upper part of the stent | 8 (38.1) | 8 (44.4) |

| Hepatic vein | 3 (14.3) | 4 (22.2) |

The performances of each Doppler-US criterion to discriminate TIPS dysfunction are summarized in Table 3.

| Variables | n paired | n patients | Sensitivity (95%CI) | Specificity (95%CI) | PPV | NPV (95%CI) |

| Portal flow modulation | 177 | 73 | 44.4 (31.2-57.6) | 79.6 (67.3-91.4) | 56.4 (37.8-76.3) | 71.1 (62.6-78.8) |

| Direction in right branch | 173 | 76 | 57.2 (44.6-70.1) | 61.7 (48.9-73.1) | 45.2 (33.7-58.3) | 72.4 (62.6-80.5) |

| Direction in left branch | 171 | 77 | 54.7 (39.6-69.7) | 66.8 (54.4-78.1) | 48.5 (34.8-63.8) | 72.1 (61.3-82.3) |

| Stent filling | 140 | 64 | 31.3 (18.8-44.2) | 81.8 (72.4-89.8) | 54.1 (36.0-71.0) | 63.4 (52.2-73.6) |

| Ascites | 218 | 87 | 27.9 (16.9-39.7) | 90.6 (84.0-95.4) | 62.9 (43.7-79.1) | 68.7 (61.0-76.1) |

| Conclusion | 218 | 87 | 39.1 (27.6-51.4) | 87.1 (79.3-93.3) | 63.5 (45.8-79.8) | 71.5 (63.6-78.5) |

Loss of portal flow modulation induced by the right atrium was more frequent in case of dysfunction 29/65 (44.6%) vs 23/112 (20.5%) (P = 0.0005). The sensitivity of this variable was 44.4% (Table 3).

Intra hepatic portal flow direction: In the right portal vein, the flow was hepatopedal in 35/61 cases of dysfunction (57.3%), whereas it was hepatopedal in 43/112 cases (38.3%) in the absence of dysfunction. This variable (hepatopedal vs hepatofugal flow) was associated with TIPS dysfunction for both right (P = 0.038) and left branches (P = 0.049). The sensitivity and specificity of this variable were 57.2% and 61.7%, respectively for the right branch, and 54.7% and 66.8%, respectively for the left branch (Table 3).

Stent filling: Stent filling was incomplete in 18/57 cases of dysfunction (31.5%) and in 15/83 cases in the absence of TIPS dysfunction (18%) (P = 0.155).

Ascites: Ascites was severe in 22/79 cases of dysfunction (27.8%) vs 13/139 cases in the absence of dysfunction (9.3%) (P = 0.001). The sensitivity and specificity of this variable were 27.9% and 90.6%, respectively (Table 3).

Stent velocity: The mean velocity within the stent was 76.6 ± 52.5 cm/s in cases of dysfunction and 76.8 ± 35.8 cm/s in the absence of dysfunction (P = 0.753).

Portal vein velocity: The mean portal vein velocity was 25.1 ± 14.9 cm/s in cases of dysfunction and 34.3 ± 19.9 cm/s in the absence of dysfunction (P = 0.008). AUC is presented in Table 4.

| Patients | Paired procedures | AUC | 95%CI | |

| Portal velocity | 80 | 192 | 0.655 | 0.553-0.749 |

| Stent velocity | 80 | 195 | 0.536 | 0.454-0.634 |

| Portal velocity delta | 63 | 150 | 0.577 | 0.485-0.679 |

| Delta + right direction | 58 | 128 | 0.626 | 0.530-0.726 |

The mean change of portal velocity relative to that measured 1 mo after TIPS insertion, called portal velocity delta, was -8.8 ± 18.1 cm/s in the dysfunction group, and -2.1 ± 22.5 cm/s in the absence of dysfunction group (P = 0.045). However, AUC of this variable is 0.577 (Table 4).

Portal velocity delta combined with right portal vein flow direction: The AUC of this association was 0.626 (Table 4).

Operator conclusion: Dysfunction was suspected from Doppler-US in 31/79 patients with certified dysfunction (39.2%), and in 18/139 patients in the absence of dysfunction (12.9%) (P = 0.0001). The sensitivity of this variable was 39.1% and its specificity was 87.1% (Table 3).

In our study, low portal vein velocity, hepatopedal flow in portal vein branches, loss of portal flow modulation, severe ascites and operator conclusion were associated with TIPS dysfunction. Nevertheless, the performance of these Doppler-US criteria for the diagnosis of TIPS dysfunction was poor.

Many studies have shown that dysfunction is associated with low main portal vein velocity[8,15,20]. Some authors have tried to define a threshold value to discriminate patent from non-patent shunts; however, results were inconsistent[8,15,20]. In our study, the AUC of main portal vein velocity was 0.655, so we cannot propose a relevant cut-off value. These results underline the difficulties to obtain a reproducible cut-off value, possibly due to the inter-individual variability of this variable. However, in our study, temporal change in main portal vein velocity relative to its baseline value was not more relevant than main portal vein velocity itself. Similarly, other authors[15,17] have reported poor sensitivity for a decrease of 33% in portal vein velocity.

The change of flow direction in the portal vein branches was significantly associated with dysfunction, both in the right and left branch. However, the sensitivity and the specificity of these variables were insufficient (all below 70%). This association has been already reported[8,14,15,18] with variable results. Kanterman et al[15] concluded this variable has a low sensitivity because intra hepatic flow reversal is a late sign of dysfunction.

Some authors have associated intrahepatic flow direction with another variable, portal vein velocity or stent velocity[14,18]. In our study, we evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of hepatopedal flow in the right portal branch combined with the decrease in portal vein velocity, but the AUC was mediocre. This is consistent with the low sensitivity we observed for each variable.

In our study, we did not find a significant modification of velocity within the shunt in cases of dysfunction. These results are consistent with some studies[16,18], whereas other authors have reported intra-stent velocity as a predictive variable[15,17]. These differences can be explained by the poor reproducibility of this measurement. Indeed, the stent velocity increases from the portal extremity to the hepatic end[21] and consequently depends on the measurement site.

The lack of cardiac modulation of the portal flow was strongly associated with TIPS dysfunction. These results are consistent with those reported by some authors[22,23].

As others[5], we observed that detection of ascites during Doppler-US examination was associated with shunt dysfunction with a high specificity (90.6%). This is consistent with the fact that ascites is a late sign of dysfunction and not a predictive one.

The conclusion of the operator was associated with dysfunction with high specificity but with low sensitivity. The negative predictive value of this variable was 71.5%, thus a dysfunction cannot be ruled out when Doppler-US examination does not suggest dysfunction. In other studies[8,15,17], this variable predicted shunt dysfunction more accurately than in our study, probably because of the monocentric design of these studies. Indeed, Doppler-US is an operator-dependent examination[24] which explains differences observed from one study to another, and difficulties to identify objective and reproducible predictors of TIPS dysfunction. Moreover, this underlines the importance of the experience of the operator. Most of the Doppler-US were performed by experienced and specialized operators in this study. In only 2 centers, some examinations have been occasionally realized by residents.

In our study, we found lower sensitivities and specificities than those reported in literature, probably because we avoided institution bias. Indeed, this study was designed as a pragmatic study and represents the reality of current practice, with about half of the French centers realizing TIPS procedure included in this study.

Moreover, dysfunctions observed in our study were mostly located in the upper part of the stent and may be more difficult to diagnose in Doppler-US.

Other authors reported similar results to ours, and failed to identify Doppler-US variables relevant to diagnose shunt dysfunction[16,20]. Interestingly, these studies were also prospective and double-blinded but included fewer patients than our study.

In our study, some procedures were realized with bare stents and other with covered stent but this has no incidence on the results as we took in account only dysfunction. Shunt dysfunction occurs frequently, even with covered stents[13]; therefore, it is still necessary to monitor shunt patency, especially to avoid the recurrence of digestive bleeding as it is a life-threatening complication. Given its poor diagnostic performance, Doppler-US is not a good diagnostic tool for routine screening across centers. Clinical supervision may be sufficient for TIPS indications such as refractory ascites, whereas early detection of shunt dysfunction appears crucial for TIPS indications such as variceal bleeding. New tools, more efficient than Doppler-US and less invasive than angiography, are needed. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound[25], as well as the measurement of azygos blood flow by magnetic resonance imaging[26] may be of interest but further studies are needed. In the meanwhile, an angiography should still be proposed, especially for bleeding indications of TIPS, sixth months after TIPS insertion because the first event of dysfunction occurs in almost half of cases at 6 mo.

In conclusion, this pragmatic study shows that the performance of Doppler-US for the detection of TIPS dysfunction is poor in current practice.

Angiography is the gold-standard procedure to evaluate transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt (TIPS) dysfunction. However, it is an invasive technic performed only in limited specialized centers. Thus, Doppler ultrasonography (Doppler-US) is frequently used for TIPS monitoring.

Despite frequent use of Doppler-US for TIPS monitoring, to date, no criterion of TIPS dysfunction have been prospectively evaluated.

The authors conducted the first large prospective multicentric evaluation of the performance of Doppler-US for the detection of TIPS dysfunction.

In routine practice, the performance of Doppler-US for the detection of TIPS dysfunction is insufficient. Thus, the gold standard remains angiography. Future researches have to focus on developing less invasive tools.

The article is aimed to assess the factors related to the prognosis of intraabdominal liposarcoma and find the optimal minimum duration for remnant tumor screening.

| 1. | Rössle M, Haag K, Ochs A, Sellinger M, Nöldge G, Perarnau JM, Berger E, Blum U, Gabelmann A, Hauenstein K. The transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt procedure for variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:165-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 522] [Cited by in RCA: 481] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lebrec D, Giuily N, Hadengue A, Vilgrain V, Moreau R, Poynard T, Gadano A, Lassen C, Benhamou JP, Erlinger S. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: comparison with paracentesis in patients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites: a randomized trial. French Group of Clinicians and a Group of Biologists. J Hepatol. 1996;25:135-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 314] [Cited by in RCA: 289] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rössle M, Ochs A, Gülberg V, Siegerstetter V, Holl J, Deibert P, Olschewski M, Reiser M, Gerbes AL. A comparison of paracentesis and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting in patients with ascites. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1701-1707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 421] [Cited by in RCA: 385] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Ginès P, Uriz J, Calahorra B, Garcia-Tsao G, Kamath PS, Del Arbol LR, Planas R, Bosch J, Arroyo V, Rodés J. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting versus paracentesis plus albumin for refractory ascites in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1839-1847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 401] [Cited by in RCA: 366] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Casado M, Bosch J, García-Pagán JC, Bru C, Bañares R, Bandi JC, Escorsell A, Rodríguez-Láiz JM, Gilabert R, Feu F. Clinical events after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: correlation with hemodynamic findings. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1296-1303. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Haskal ZJ, Pentecost MJ, Soulen MC, Shlansky-Goldberg RD, Baum RA, Cope C. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt stenosis and revision: early and midterm results. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;163:439-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lind CD, Malisch TW, Chong WK, Richards WO, Pinson CW, Meranze SG, Mazer M. Incidence of shunt occlusion or stenosis following transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1277-1283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sanyal AJ, Freedman AM, Luketic VA, Purdum PP 3rd, Shiffman ML, DeMeo J, Cole PE, Tisnado J. The natural history of portal hypertension after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:889-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Haskal ZJ. Improved patency of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts in humans: creation and revision with PTFE stent-grafts. Radiology. 1999;213:759-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Andrews RT, Saxon RR, Bloch RD, Petersen BD, Uchida BT, Rabkin JM, Loriaux MM, Keller FS, Rösch J. Stent-grafts for de novo TIPS: technique and early results. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1999;10:1371-1378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bureau C, Garcia-Pagan JC, Otal P, Pomier-Layrargues G, Chabbert V, Cortez C, Perreault P, Péron JM, Abraldes JG, Bouchard L. Improved clinical outcome using polytetrafluoroethylene-coated stents for TIPS: results of a randomized study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:469-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 345] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rossi P, Salvatori FM, Fanelli F, Bezzi M, Rossi M, Marcelli G, Pepino D, Riggio O, Passariello R. Polytetrafluoroethylene-covered nitinol stent-graft for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation: 3-year experience. Radiology. 2004;231:820-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Perarnau JM, Le Gouge A, Nicolas C, d’Alteroche L, Borentain P, Saliba F, Minello A, Anty R, Chagneau-Derrode C, Bernard PH. Covered vs. uncovered stents for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: a randomized controlled trial. J Hepatol. 2014;60:962-968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lafortune M, Martinet JP, Denys A, Patriquin H, Dauzat M, Dufresne MP, Colombato L, Pomier-Layrargues G. Short- and long-term hemodynamic effects of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: a Doppler/manometric correlative study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164:997-1002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kanterman RY, Darcy MD, Middleton WD, Sterling KM, Teefey SA, Pilgram TK. Doppler sonography findings associated with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt malfunction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:467-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Owens CA, Bartolone C, Warner DL, Aizenstein R, Hibblen J, Yaghmai B, Wiley TE, Layden TJ. The inaccuracy of duplex ultrasonography in predicting patency of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:975-980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zizka J, Eliás P, Krajina A, Michl A, Lojík M, Ryska P, Masková J, Hůlek P, Safka V, Vanásek T. Value of Doppler sonography in revealing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt malfunction: a 5-year experience in 216 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:141-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Abraldes JG, Gilabert R, Turnes J, Nicolau C, Berzigotti A, Aponte J, Bru C, Bosch J, García-Pagán JC. Utility of color Doppler ultrasonography predicting tips dysfunction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2696-2701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rutter CM. Bootstrap estimation of diagnostic accuracy with patient-clustered data. Acad Radiol. 2000;7:413-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bureau C, Garcia Pagan JC, Layrargues GP, Metivier S, Bellot P, Perreault P, Otal P, Abraldes JG, Peron JM, Rousseau H. Patency of stents covered with polytetrafluoroethylene in patients treated by transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: long-term results of a randomized multicentre study. Liver Int. 2007;27:742-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bodner G, Peer S, Fries D, Dessl A, Jaschke W. Color and pulsed Doppler ultrasound findings in normally functioning transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Eur J Ultrasound. 2000;12:131-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Puttemans T, Van Beers BE, Goffette P, Dardenne AN, Pringot J. [Follow-up of TIPS: evaluation of signs of dysfunction with Doppler ultrasonography]. J Radiol. 1996;77:1201-1206. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Sheiman RG, Vrachliotis T, Brophy DP, Ransil BJ. Transmitted cardiac pulsations as an indicator of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt function: initial observations. Radiology. 2002;224:225-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sacerdoti D, Gaiani S, Buonamico P, Merkel C, Zoli M, Bolondi L, Sabbà C. Interobserver and interequipment variability of hepatic, splenic, and renal arterial Doppler resistance indices in normal subjects and patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 1997;27:986-992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Micol C, Marsot J, Boublay N, Pilleul F, Berthezene Y, Rode A. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound: a new method for TIPS follow-up. Abdom Imaging. 2012;37:252-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Debatin JF, Zahner B, Meyenberger C, Romanowski B, Schöpke W, Marincek B, Fuchs WA. Azygos blood flow: phase contrast quantitation in volunteers and patients with portal hypertension pre- and postintrahepatic shunt placement. Hepatology. 1996;24:1109-1115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: France

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Amornyotin S S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D