Published online Jan 18, 2017. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v9.i2.99

Peer-review started: August 23, 2016

First decision: September 28, 2016

Revised: October 24, 2016

Accepted: November 16, 2016

Article in press: November 17, 2016

Published online: January 18, 2017

Processing time: 150 Days and 4.5 Hours

To determine the impact of transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt (TIPS) on post liver transplantation (LT) outcomes.

Utilizing the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database, we compared patients who underwent LT from 2002 to 2013 who had underwent TIPS to those without TIPS for the management of ascites while on the LT waitlist. The impact of TIPS on 30-d mortality, length of stay (LOS), and need for re-LT were studied. For evaluation of mean differences between baseline characteristics for patients with and without TIPS, we used unpaired t-tests for continuous measures and χ2 tests for categorical measures. We estimated the impact of TIPS on each of the outcome measures. Multivariate analyses were conducted on the study population to explore the effect of TIPS on 30-d mortality post-LT, need for re-LT and LOS. All covariates were included in logistic regression analysis.

We included adult patients (age ≥ 18 years) who underwent LT from May 2002 to September 2013. Only those undergoing TIPS after listing and before liver transplant were included in the TIPS group. We excluded patients with variceal bleeding within two weeks of listing for LT and those listed for acute liver failure or hepatocellular carcinoma. Of 114770 LT in the UNOS database, 32783 (28.5%) met inclusion criteria. Of these 1366 (4.2%) had TIPS between the time of listing and LT. We found that TIPS increased the days on waitlist (408 ± 553 d) as compared to those without TIPS (183 ± 330 d), P < 0.001. Multivariate analysis showed that TIPS had no effect on 30-d post LT mortality (OR = 1.26; 95%CI: 0.91-1.76) and re-LT (OR = 0.61; 95%CI: 0.36-1.05). Pre-transplant hepatic encephalopathy added 3.46 d (95%CI: 2.37-4.55, P < 0.001), followed by 2.16 d (95%CI: 0.92-3.38, P = 0.001) by TIPS to LOS.

TIPS did increase time on waitlist for LT. More importantly, TIPS was not associated with 30-d mortality and re-LT, but it did lengthen hospital LOS after transplantation.

Core tip: The study was completed to determine the impact of transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt (TIPS) on post liver transplantation (LT) outcomes. Utilizing the United Network for Organ Sharing database, we compared patients who underwent LT from 2002 to 2013 who had undergone TIPS to those without TIPS for the management of ascites while on the LT waitlist. The impact of TIPS on 30-d mortality, length of stay (LOS), and need for re-LT were studied. TIPS was not commonly used in patients with ascites on the waitlist but did increase time on waitlist for LT. More importantly, TIPS was not associated with 30-d mortality and re-LT, but it did increase hospital LOS after transplantation.

- Citation: Mumtaz K, Metwally S, Modi RM, Patel N, Tumin D, Michaels AJ, Hanje J, El-Hinnawi A, Hayes Jr D, Black SM. Impact of transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt on post liver transplantation outcomes: Study based on the United Network for Organ Sharing database. World J Hepatol 2017; 9(2): 99-105

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v9/i2/99.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v9.i2.99

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS) play an important role in the treatment of recurrent esophageal varices, bleeding gastric varices and refractory ascites. Multiple randomized trials and meta-analyses have reported the superiority of TIPS over large volume paracentesis in controlling refractory ascites with no effect on long-term survival[1-8]. One study compared 149 patients with refractory ascites allocated to TIPS and 156 to paracentesis with significant improvement in the TIPS population regarding transplant-free survival of cirrhotic patients with refractory ascites[6].

A few single-center studies have reported the impact of TIPS on liver transplant metrics[9-11]. When comparing TIPS vs non-TIPS patients, studies revealed comparable transfusion requirements and operative time between the two cohorts and also demonstrated operative mortality and early graft function not to be influenced by TIPS placement[9,10]. In fact, TIPS may offer an advantage in reducing ascites at the time of transplantation, which in turn may expedite the transplant time[11].

Other single center studies explored the impact of TIPS on post-transplant survival and found no significant difference[12-14]. Guerrini et al[15], however, found that patients who underwent TIPS pre-liver transplantation (pre-LT) had a lower risk of mortality at 1 year after LT. These potential advantages associated with the use of TIPS, however, are balanced by technical complications associated with it at time of LT[16].

Previously, most single center studies and meta-analyses evaluating the utility of TIPS in the context of LT have explored the survival at 1 year or longer[12-14]. It appears that TIPS may improve portal hypertension related issues in immediate post-transplant setting by reducing the flow of blood in the collateral circulation, thus improving portal supply to the graft[15]. Keeping in mind the mechanism by which TIPS may be helpful or disadvantageous, it’s prudent to study short-term outcomes such as 30-d mortality and re-LT.

We utilized the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database to determine if TIPS had an influence on short-term outcomes of LT. We hypothesized that TIPS is not associated with an increase in 30-d post LT mortality and rate of re-LT.

A retrospective cohort study was performed on adult LT candidates who were registered in the Organ Procure–ment and Transplant Network (OPTN) Standard Transplant Analysis and Research Database (Reference: UNOS/Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network Standard Transplant Analysis and Research Database. Available from: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/about-data/, Accessed September 6, 2013). The study was approved by the Nationwide Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board with a waiver of individual consent (IRB14-00716). The UNOS/OPTN liver database was queried for all patients with cirrhosis listed from May 2002 to September 2013. Each first-time LT candidate listed was tracked until death. All patients with TIPS for ascites who ultimately underwent LT were included in this sample.

The data available from the UNOS Registry included status of TIPS in patients with ascites. Other variables included in analysis were gender, age, diabetes mellitus, body mass index (BMI) at listing, cold ischemia time (CIT), waitlist hepatic encephalopathy, etiology of liver disease (alcoholic vs other), model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score at listing, MELD score at LT; biochemical tests including serum creatinine, bilirubin, albumin, and international normalized ratio (INR). We studied various outcomes including mortality at 30-d, need for re-LT and hospital length of stay (LOS) during admission for LT.

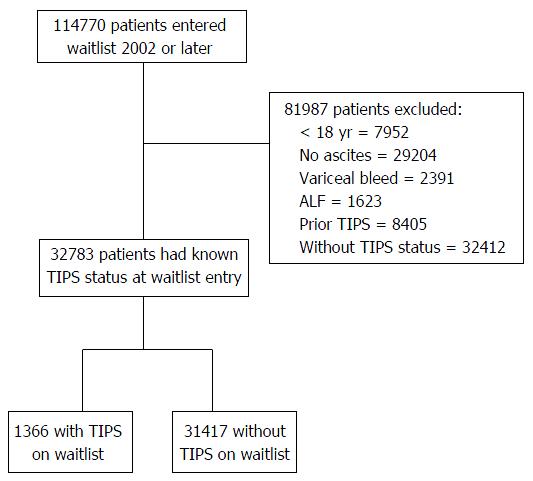

We included adult patients (age ≥ 18 years) who underwent LT from May 2002 to September 2013 [i.e., after the inception of the MELD score and use of expanded-polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) covered TIPS]. Only those undergoing TIPS after listing and before liver transplant were included in the TIPS group. We excluded patients with variceal bleeding within two weeks of listing (in order to exclude TIPS for variceal bleed) for LT and those listed for acute liver failure or hepatocellular carcinoma. After application of exclusion criteria (Figure 1) the analytic sample consisted of 32783/114770 (28.5%) patients with ascites who underwent LT and had a known TIPS status. Among these 32783 patients with ascites, 1366 patients underwent TIPS while 31417 patients did not undergo TIPS.

All values were expressed as means ± SD for continuous measures, and counts and percentages for categorical variables. For all analyses, a P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For evaluation of mean differences between baseline characteristics for patients with and without TIPS, we used unpaired t-tests for continuous measures and χ2 tests for categorical measures. We estimated the impact of TIPS on each of the outcome measures. Multivariate analyses were conducted on the study population to explore the effect of TIPS on 30-d mortality post-LT, need for re-LT and LOS. All covariates were included in logistic regression analysis. All analyses were performed using Stata/MP, version 13.1 (College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). The statistical review of this study was performed by a biomedical statistician.

After applying the inclusion/exclusion criteria a total of 32783 patients with ascites from database were selected. A total of 1366 (4.2%) underwent TIPS for management of refractory ascites while awaiting LT (Figure 1). Those without TIPS (n = 31417) were selected as a control group for comparison.

Demographics such as gender, age and BMI were comparable in the two groups; albumin and CIT were also equally distributed (Table 1). Patients with TIPS on waitlist had a lower mean MELD score at time of listing (16.6 ± 6.7) as compared to those without TIPS (19.7 ± 8.9), (P < 0.001). Plausibly, TIPS group had a lower creatinine, bilirubin and INR. Interestingly, the MELD score at transplantation was higher in the TIPS group (23.2 ± 9.2) as compared to without TIPS group (22.6 ± 9.8) (P = 0.03). Plausibly, there were less patients with severe hepatic encephalopathy (HE) in the TIPS group (n = 68; 4.9%) as compared to without TIPS (n = 2218; 7%) (P = 0.01).

| Variables | TIPS on waitlist (n = 1366; % or mean ± SD) | Non TIPS on waitlist (n = 31417; % or mean ± SD) | P-values |

| Male candidate | 943 (69) | 21374 (68) | 0.43 |

| Candidate race | < 0.001 | ||

| White | 1072 (78.4) | 23063 (73.4) | |

| Black | 75 (5.4) | 2865 (9.1) | |

| Other | 219 (16) | 5489 (17.4) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 380 (28) | 7769 (24.8) | 0.009 |

| ALD | 311 (22.7) | 6615 (21) | 0.13 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 0.01 | ||

| None | 373 (27.3) | 8409 (26.7) | |

| Grade 1-2 | 925 (67.7) | 20790 (66.1) | |

| Grade 3-4 | 68 (4.9) | 2218 (7) | |

| Arterial hypertension | 68 (14.8) | 2254 (19.7) | 0.01 |

| Age | 53.5 ± 8.5 | 53.6 ± 9.3 | 0.65 |

| MELD score at listing | 16.6 ± 6.6 | 19.66 ± 8.8 | < 0.001 |

| Creatinine | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 1.4 ± 1.2 | < 0.001 |

| Bilirubin | 4.1 ± 6.3 | 6.61 ± 9.0 | < 0.001 |

| INR | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | < 0.001 |

| Albumin | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 0.66 |

| BMI at list entry | |||

| Continuous (kg/m2) | 28.8 ± 5.6 | 28.8 ± 5.7 | 0.89 |

| Dichotomous (≥ 26 kg/m2) | 905 (66.4) | 20747 (66.2) | 0.85 |

| Cold ischemia time | |||

| Continuous (h) | 7.1 ± 3.7 | 6.9 ± 3.5 | 0.03 |

| Dichotomous (> 12 h) | 66 (5.0) | 1360 (4.5) | 0.38 |

| MELD score at transplantation | 23.1 ± 9.1 | 22.6 ± 9.7 | 0.03 |

On univariate analysis (Table 2), we found that TIPS increases the days on LT waitlist (408 ± 553 d) as compared to those without TIPS (183 ± 330 d), (P < 0.001). TIPS group had comparable 30-d post LT mortality as compared to non-TIPS group (46; 3.51% vs 915; 3.05%; P = 0.34). There was also a comparable re-LT rate at 30 d (15; 1.1% vs 560; 1.78%; P = 0.06) and hospital LOS (17.58 vs 16.62; P = 0.12) between the two groups.

| TIPS on waitlist (n = 1366) % or mean ± SD | No TIPS on waitlist (n = 31417) % or mean ± SD | P-values | |

| Days on LT waitlist | 408 ± 552.6 | 183 ± 330.5 | < 0.001 |

| Mortality within 30 d | 46 (3.5) | 915 (3.0) | 0.344 |

| Length of hospital stay | 17.58 ± 22.4 | 16.62 ± 22.1 | 0.118 |

| Re-LT at 30 d | 15 (1.1) | 560 (1.8) | 0.06 |

On logistic regression, TIPS had no effect on 30-d post LT mortality (OR = 1.26; 95%CI: 0.91-1.75). However, the significant predictors of mortality at 30-d were advanced age (OR = 1.02; 95%CI: 1.01-1.03, P < 0.001), low serum albumin (OR = 0.88; 95%CI: 0.79-0.98, P = 0.029), and increasing CIT (OR = 1.04; 95%CI: 1.02-1.05, P < 0.001). Another predictor of 30-d mortality was bilirubin (OR = 1.014; 95%CI: 1.004-1.024; P = 0.008 (Table 3).

| Variable | OR (95%CI) | P-values |

| TIPS | 1.26 (0.90-1.75) | 0.17 |

| Male candidate | 0.83 (0.71-0.95) | 0.01 |

| Candidate race | ||

| White | Ref. | |

| Black | 1.08 (0.85-1.37) | 0.54 |

| Other | 1.08 (0.90-1.29) | 0.40 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.12 (0.95-1.31) | 0.17 |

| ALD | 0.89 (0.74-1.07) | 0.22 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | ||

| None | Ref. | |

| Grade 1-2 | 0.86 (0.73-1.01) | 0.06 |

| Grade 3-4 | 1.12 (0.85-1.47) | 0.41 |

| Age | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | < 0.001 |

| MELD score | 1.02 (1.00-1.04) | 0.05 |

| Creatinine | 1.03 (0.97-1.10) | 0.33 |

| Bilirubin | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | 0.008 |

| INR | 0.97 (0.86-1.09) | 0.59 |

| Albumin | 0.88 (0.79-0.98) | 0.03 |

| BMI | 1.00 (0.99-1.02) | 0.86 |

| Cold ischemia time | 1.04 (1.02-1.05) | < 0.001 |

On logistic regression, TIPS was not associated with re-LT at 30 d (OR = 0.61; 95%CI: 0.36-1.05). Predictors of re-LT at 30 d included advanced age (OR = 0.97; 95%CI: 0.96-0.98; P < 0.001), creatinine (OR = 0.87; 95%CI: 0.77-0.99; P = 0.032) and CIT (OR = 1.05; 95%CI: 1.03-1.07; P < 0.001) (Table 4).

| Variable | OR (95%CI) | P-values |

| TIPS | 0.61 (0.36-1.05) | 0.07 |

| Male candidate | 1.02 (0.85-1.24) | 0.81 |

| Candidate race | ||

| White | Ref. | |

| Black | 1.22 (0.91-1.64) | 0.18 |

| Other | 1.05 (0.83-1.32) | 0.69 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.98 (0.78-1.21) | 0.83 |

| ALD | 0.98 (0.78-1.24) | 0.90 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | ||

| None | Ref. | |

| Grade 1-2 | 0.92 (0.76-1.13) | 0.44 |

| Grade 3-4 | 1.02 (0.69-1.51) | 0.91 |

| Age | 0.97 (0.96-0.98) | < 0.001 |

| MELD score | 0.99 (0.97-1.02) | 0.51 |

| Creatinine | 0.87 (0.77-0.99) | 0.03 |

| Bilirubin | 0.99 (0.98-1.02) | 0.54 |

| INR | 1.01 (0.86-1.18) | 0.9 |

| Albumin | 1.03 (0.89-1.19) | 0.65 |

| BMI | 1.005 (0.98-1.02) | 0.54 |

| Cold ischemia time | 1.05 (1.03-1.07) | < 0.001 |

Advanced HE (grade 3-4) on waitlist contributed most days to LOS (β = 3.46; 95%CI: 2.37-4.55, P < 0.001), followed by TIPS (β = 2.16; 95%CI: 0.92-3.38, P = 0.001). Other factors that contributed to LOS were black race (β = -1.58; 95%CI: -2.46 to -0.69, P < 0.001) and advanced age (β = 0.09; 95%CI: 0.06-0.11, P < 0.001). High MELD score, INR, albumin, BMI and CIT also significantly contributed to LOS after LT (Table 5).

| Variable | β (95%CI) | P-values |

| TIPS | 2.16 (0.92-3.38) | 0.001 |

| Male candidate | -1.99 (-2.52-1.46) | < 0.001 |

| Candidate race | ||

| White | Ref. | |

| Black | -1.58 (-2.46-0.69) | < 0.001 |

| Other | 0.11 (-0.53-0.77) | 0.72 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.52 (-0.05-1.10) | 0.07 |

| ALD | 0.17 (-0.44-0.79) | 0.57 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | ||

| None | Ref. | |

| Grade 1-2 | -0.10 (-0.66-0.46) | 0.73 |

| Grade 3-4 | 3.46 (2.37-4.55) | < 0.001 |

| Age | 0.09 (0.06-0.11) | < 0.001 |

| MELD score | 0.37 (0.31-0.44) | < 0.001 |

| Creatinine | 0.05 (-0.21-0.31) | 0.71 |

| Bilirubin | 0.03 (-0.008-0.08) | 0.1 |

| INR | -1.06 (-1.50-0.61) | < 0.001 |

| Albumin | -0.63 (-1.01-0.24) | 0.001 |

| BMI | -0.05 (-0.100-0.01) | 0.01 |

| Cold ischemia time | 0.36 (0.29-0.43) | < 0.001 |

| Constant | 7.83 (5.38-10.27) | < 0.001 |

The most important finding of the current study is that TIPS for the treatment of ascites in the MELD era for LT is not associated with heightened 30-d mortality or the need for re-transplantation. However, hospital LOS was increased in patients with TIPS which may point to post-operative morbidity. TIPS was found to increase time on waitlist in patients with ascites.

Our findings of safety of TIPS in terms of short term mortality and need for re-LT is in line with multiple other studies, as these also did not find any difference in operative time, transfusion and LOS[9,12,14,17]. One of the largest retrospective studies of 207 patients explored the impact of TIPS on post-transplant survival and graft loss and found no significant difference[12]. In fact, a recent study went even further to find lower risk of mortality in TIPS group at 1 year after LT[15].

Our study holds many advantages to prior studies including the use of a national database and large sample size. Furthermore, our study had increased homogeneity as it was limited to those undergoing TIPS for refractory ascites and was limited to a study period in the post-MELD era and with more homogeneity in shunt type (i.e., ePTFE covered).

Existing literature on LOS is variable with certain studies describing intra-operative complications in patients who have undergone TIPS[16]. On the other hand, additional studies have not found TIPS to affect the LOS in post LT setting[14,18]. It has been shown in our study that advanced HE (grade 3-4) on waitlist cirrhotics contributes the most to LOS adding 3.5 d followed by TIPS insertion which prolonged stay by an average of 2.16 d. This finding is remarkable given encephalopathy is a known complication of TIPS[7,8]. We can hypothesize that TIPS insertion may contribute to ongoing encephalopathy and therefore increase length of hospital stay.

Among other predictors of increased LOS were advanced age, high MELD score and CIT. All these factors are recognized predictors of increased LOS and reported in literature[19,20]. Of note, the TIPS group in our study began with a lower MELD score at the time of listing but had higher MELD scores at the time of LT. This finding suggests patients undergoing TIPS were able to survive longer on the wait list with continued progression of liver disease at the time of LT. More advanced disease among TIPS patients would explain increased LOS post-LT.

We found that increased time on the waitlist in the TIPS group was consistent with findings from single center studies[18]. Several randomized controlled trials and a meta-analysis of individual patient data also found TIPS superior to repeated paracentesis in increasing time on waitlist and therefore transplant free survival[2,5,6]. The increased time on LT wait list may be explained by decreased portal hypertension produced by the TIPS and mortality associated with complications of portal hypertension. One study found that TIPS lowered mortality rate while on waitlist and decreased need for transplantation[21]. Hence, it is possible TIPS can be utilized as a bridge to transplant and even to improve waitlist survival of listed patients.

Our findings demonstrate the challenge of using TIPS in patients who need to undergo LT. Following TIPS placement, this patient population has an increased wait time for LT, yet suffers comparable immediate post procedural mortality as their non-TIPS counterparts. This longer time on the waitlist may allow for other decompensated non-TIPS patients with higher MELD scores to undergo LT first. Thus, it appears that a disparity is created where the patient population requiring more advanced treatment of ascites (i.e., TIPS) have increased time on waitlist through improvement of the MELD score and therefore experience a delay in transplantation. Based on our findings, we propose an idea to potentially provide special circumstances to patients requiring TIPS on the waitlist for LT as their outcomes after transplantation are not influenced by placement of the shunt. An example of special circumstances could be exceptional MELD points to avoid further delay in LT.

Limitations of our study are mainly related to availability of variables in the UNOS database. This database only lists TIPS status at the time of LT recipient registration and does not provide information on control and recurrence of tense ascites, post TIPS encephalopathy, intra- and post-LT information such as operative time and blood product transfusion requirements. Waitlist mortality, intensive care unit stay, and complications of TIPS placement such as TIPS migration and endovascular stenting were also not available to us. Due to these database limitations we cannot directly measure the number of patients on waitlist undergoing TIPS or the waitlist mortality. As a result, days on waitlist had to be used as a surrogate measure for waitlist mortality and transplant free survival.

In conclusion, we found that TIPS had no effect on the 30-d mortality after LT and the need for re-LT. TIPS increased time on LT waitlist while also increasing length of hospital stay post-LT. It was found that TIPS is not a commonly used intervention for the management of ascites in patients on the waitlist for LT. With TIPS not influencing 30-d mortality and need for re-LT, it appears that more patients may benefit from its use. However, one of the downsides of using TIPS could be a potential delay in LT due to improvement in MELD score. These important factors must be considered and discussed with patients before pursuing TIPS procedure.

Prior studies exploring the role of transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt (TIPS) with regards to cirrhotic patients being evaluated for liver transplant were limited by small sample sizes, single center studies, and heterogeneous study groups that resulted in poor generalizability. Further, these studies were completed prior to advent of expanded-polytetrafluoroethylene covered stents and introduction of model for end-stage liver disease allocation system. Here the authors would like to utilize the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database to address the effect of TIPS on waitlist times, liver transplantation (LT) morbidity and mortality, and hospital length of stay.

Since its inception, TIPS has been touted as a potential bridge to LT by possibly improving transplant free survival. Studies such as that performed by Berry et al have recently used the UNOS data base to confirm TIPS’ role in improving transplant free survival and support the notion that TIPS is a bridge to LT.

To our knowledge no study has utilized the UNOS database in exploring post-LT outcomes in the TIPS population. The study confirmed findings of prior single center studies that TIPS does not significantly affect post-LT outcomes. Of note, their large study group size adds power and improves generalizability of these findings. Short term outcomes were their primary focus given the concern for potential for intra-operative LT complications in patients who have undergone TIPS.

The authors’ findings support prior single center and more recent meta-analyses and database reviews in confirming increased transplant free survival while not affecting post-LT outcomes. The study supports the notion that TIPS can be utilized as a bridge to transplantation. Prospective studies will be necessary to further elucidate the influence of TIPS on LT outcomes and the potential detriments resulting from prolonged waitlist times.

CIT: Cold ischemia time; ePTFE: Expanded-polytetrafluoroethylene; HE: Hepatic encephalopathy; LOS: Length of hospital stay; LT: Liver transplantation; LVP: Large volume paracentesis; MELD: Model for end-stage liver disease; TIPS: Transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt; UNOS: United Network for Organ Sharing.

The paper is well written and the design is good.

| 1. | Lebrec D, Giuily N, Hadengue A, Vilgrain V, Moreau R, Poynard T, Gadano A, Lassen C, Benhamou JP, Erlinger S. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: comparison with paracentesis in patients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites: a randomized trial. French Group of Clinicians and a Group of Biologists. J Hepatol. 1996;25:135-144. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Rössle M, Ochs A, Gülberg V, Siegerstetter V, Holl J, Deibert P, Olschewski M, Reiser M, Gerbes AL. A comparison of paracentesis and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting in patients with ascites. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1701-1707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 421] [Cited by in RCA: 386] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Ginès P, Uriz J, Calahorra B, Garcia-Tsao G, Kamath PS, Del Arbol LR, Planas R, Bosch J, Arroyo V, Rodés J. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting versus paracentesis plus albumin for refractory ascites in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1839-1847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 401] [Cited by in RCA: 367] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Sanyal AJ, Genning C, Reddy KR, Wong F, Kowdley KV, Benner K, McCashland T. The North American Study for the Treatment of Refractory Ascites. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:634-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Salerno F, Merli M, Riggio O, Cazzaniga M, Valeriano V, Pozzi M, Nicolini A, Salvatori F. Randomized controlled study of TIPS versus paracentesis plus albumin in cirrhosis with severe ascites. Hepatology. 2004;40:629-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | Salerno F, Cammà C, Enea M, Rössle M, Wong F. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for refractory ascites: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:825-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 396] [Cited by in RCA: 378] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Rosado B, Kamath PS. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: an update. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:207-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Patidar KR, Sydnor M, Sanyal AJ. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Clin Liver Dis. 2014;18:853-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Barbier L, Hardwigsen J, Borentain P, Biance N, Daghfous A, Louis G, Botta-Fridlund D, Le Treut YP. Impact of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting on liver transplantation: 12-year single-center experience. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2014;38:155-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gimson AE. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt and liver transplantation--how safe is the bridge? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:821-822. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Somberg KA, Lombardero MS, Lawlor SM, Ascher NL, Lake JR, Wiesner RH, Zetterman RK. A controlled analysis of the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in liver transplant recipients. The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Liver Transplantation Database. Transplantation. 1997;63:1074-1079. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Levi Sandri GB, Lai Q, Lucatelli P, Melandro F, Guglielmo N, Mennini G, Berloco PB, Fanelli F, Salvatori FM, Rossi M. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for a wait list patient is not a contraindication for orthotopic liver transplant outcomes. Exp Clin Transplant. 2013;11:426-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Moreno A, Meneu JC, Moreno E, Fraile M, García I, Loinaz C, Abradelo M, Jiménez C, Gomez R, García-Sesma A. Liver transplantation and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:1869-1870. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Menegaux F, Baker E, Keeffe EB, Monge H, Egawa H, Esquivel CO. Impact of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt on orthotopic liver transplantation. World J Surg. 1994;18:866-870; discussion 870-871. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Guerrini GP, Pleguezuelo M, Maimone S, Calvaruso V, Xirouchakis E, Patch D, Rolando N, Davidson B, Rolles K, Burroughs A. Impact of tips preliver transplantation for the outcome posttransplantation. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:192-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Millis JM, Martin P, Gomes A, Shaked A, Colquhoun SD, Jurim O, Goldstein L, Busuttil RW. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: impact on liver transplantation. Liver Transpl Surg. 1995;1:229-233. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Irausquin H. The value of clinical chemistry data in animal screening studies for safety evaluation. Toxicol Pathol. 1992;20:515-517; discussion 515-517. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Freeman RB, FitzMaurice SE, Greenfield AE, Halin N, Haug CE, Rohrer RJ. Is the transjugular intrahepatic portocaval shunt procedure beneficial for liver transplant recipients? Transplantation. 1994;58:297-300. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Foxton MR, Al-Freah MA, Portal AJ, Sizer E, Bernal W, Auzinger G, Rela M, Wendon JA, Heaton ND, O’Grady JG. Increased model for end-stage liver disease score at the time of liver transplant results in prolonged hospitalization and overall intensive care unit costs. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:668-677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Buchanan P, Dzebisashvili N, Lentine KL, Axelrod DA, Schnitzler MA, Salvalaggio PR. Liver transplantation cost in the model for end-stage liver disease era: looking beyond the transplant admission. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:1270-1277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Berry K, Lerrigo R, Liou IW, Ioannou GN. Association Between Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt and Survival in Patients With Cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:118-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Fava G, Haddad LBD, Kasztelan-Szczerbinska B, Zheng YB S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D