Published online May 28, 2017. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v9.i15.704

Peer-review started: February 1, 2017

First decision: March 6, 2017

Revised: March 16, 2017

Accepted: April 23, 2017

Article in press: April 24, 2017

Published online: May 28, 2017

Processing time: 113 Days and 18.4 Hours

To study the trend of hepatocellular carcinoma incidence after correcting the misclassification in registering cancer incidence across Iranian provinces in cancer registry data.

Incidence data of hepatocellular carcinoma were extracted from Iranian annual of national cancer registration reports 2004 to 2008. A Bayesian method was implemented to estimate the rate of misclassification in registering cancer incidence in neighboring province. A beta prior is considered for misclassification parameter. Each time two neighboring provinces were selected to be entered in the Bayesian model based on their expected coverage of cancer cases which is reported by medical university of the province. It is assumed that some cancer cases from a province that has an expected coverage of cancer cases lower than 100% are registered in their neighboring facilitate province with more than 100% expected coverage.

There is an increase in the rate of hepatocellular carcinoma in Iran. Among total of 30 provinces of Iran, 21 provinces were selected to be entered to the Bayesian model for correcting the existed misclassification. Provinces with more medical facilities of Iran are Tehran (capital of the country), Razavi Khorasan in north-east of Iran, East Azerbaijan in north-west of the country, Isfahan in central part and near to Tehran, Khozestan and Fars in south and Mazandaran in north of the Iran, had an expected coverage more than their expectation. Those provinces had significantly higher rates of hepatocellular carcinoma than their neighboring provinces. In years 2004 to 2008, it was estimated to be on average 34% misclassification between North Khorasan province and Razavi Khorasan, 43% between South Khorasan province and Razavi Khorasan, 47% between Sistan and balochestan province and Razavi Khorasan, 23% between West Azerbaijan province and East Azerbaijan province, 25% between Ardebil province and East Azerbaijan province, 41% between Hormozgan province and Fars province, 22% betweenChaharmahal and bakhtyari province and Isfahan province, 22% between Kogiloye and boyerahmad province and Isfahan, 22% between Golestan province and Mazandaran province, 43% between Bushehr province and Khozestan province, 41% between Ilam province and Khuzestan province, 42% between Qazvin province and Tehran province, 44% between Markazi province and Tehran, and 30% between Qom province and Tehran.

Accounting and correcting the regional misclassification is necessary for identifying high risk areas and planning for reducing the cancer incidence.

Core tip: In many developing countries and even in some developed countries some errors occur in disease registry system. Since registered data is used for planning at the national and sub-national level, correcting the existed errors has a great importance. One of these errors is misclassification in registering cancer incidence. It occurs because some patients from divested provinces prefer to get more qualified diagnostic and treatment services at their adjacent provinces with more medical facilities without mentioning their permanent residence. The aim of this study is to investigate the trend of hepatocellular carcinoma after correcting for misclassification error in Iran’s cancer registry using Bayesian method.

- Citation: Hajizadeh N, Baghestani AR, Pourhoseingholi MA, Ashtari S, Fazeli Z, Vahedi M, Zali MR. Trend of hepatocellular carcinoma incidence after Bayesian correction for misclassified data in Iranian provinces. World J Hepatol 2017; 9(15): 704-710

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v9/i15/704.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v9.i15.704

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the 5th most common cancer worldwide[1]. It is the fifth most common cancer in men (7.5% of the total, 554000 cases) and the ninth most common cancer in women (3.4% of the total, 228000 cases). Eighty-three percent of the estimated new cancer cases worldwide occurred in less developed regions in 2012 that 50% of that belongs to China alone[2]. HCC is the second most common cause of cancer death in the world[1] and it is estimated to be responsible for nearly 746000 deaths based on Globocan report 2012[2]. The major risk factors for HCC, are infection with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus[3]. The most common cause of HCC in Iran is HBV and 80% of HCC cases are positive for at least one of the markers of HBV[4-6]. It is estimated that approximately 1.5 million people in the country are infected with this virus and 15% to 40% of them are at risk of developing cirrhosis or HCC[7,8]. The other known risk factors are Gender (HCC is more common in males than in females), Race (Pacific Islanders and Asian Americans have the highest rates of HCC, followed by American Indians and Hispanics, African Americans, and whites), Cirrhosis, Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, Heavy alcohol use, Obesity, Aflatoxins and Tobacco use[9]. Overall mortality to incidence ratio of HCC is 0.95, so the geographical patterns of incidence and mortality are similar[2,3]. The regions of high incidence are Eastern Asia and South-Eastern Asia, the regions of intermediate incidence are Southern Europe and Northern America (9.3) and the lowest rates are occur in South-Central Asia and Northern Europe[2]. Iran is located in Middle East, an area with low risk for HCC[1,10] with an annual incidence much less than 5 per 100000 populations[4,11] but, while prognosis for HCC is very poor, the true prevalence of HCC in Iran is unknown and up to 40% of its death statistics are underreported; so it is not considered as an uncommon malignancy[2-4].

Nowadays having a thorough information of geographic distribution of cancers has become so important[12]. Cancer registries are known as the main resource of epidemiologic data by registering the mortality, incidence, prevalence and survival for different disease in a systematic manner that is used by health policy makers for cancer control planning and evaluation of cancer screening programs, detecting the impact of treatments and interventions, and allocating of resources to various provinces based on their need to healthcare facilities[13]. In addition to poor diagnosis of HCC, some patients want to get healthcare in facilitate neighboring provinces outside their resident without reporting their permanent address. It causes misclassification error in cancer registry system. Misclassification error is the disagreement between the observed and the true value. The expected coverage of cancer incidence in different provinces is the evidence of existence of misclassification error; that the observed rate of incidence is more than expected rate in some of the provinces, but then, it is much less than expected rate in their neighboring provinces[14], while it is expected that the rate of cancer incidence be about the same in neighboring provinces that are similar in lifestyle and environmental conditions. Misclassification error in registered data leads to erroneous estimates of the incidence rates of cancer in different provinces and consequently affects need assessments. There are two methods to correct for misclassification error. The first is using a valid data that usually is not available or it is so time consuming and costly to valid a sample data and generalizing the results to the population[15]. The second is implementing Bayesian method. This is a statistical method that can be used to import the researcher’s prior knowledge about the rate of misclassification to the analysis and updating prior information with observed data to estimate the misclassification rate[16].

The aim of this study is to assess the trend of HCC incidence after correcting for misclassification error in registering cancer incidence in neighboring provinces of Iran, using a Bayesian method.

Incidence data of HCC was extracted from Iranian annual of national cancer registration report from 2004 to 2008[14]. Annual of 2008 was the last available data to use. The Age Standardized Rate (ASR) for HCC [coded based on the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10; C22)] was calculated for all provinces of Iran in each year with direct standardization method and using the standard population reported by Word Health Organization for both genders and four age groups (0-14 years, 15-49 years, 50-69 years and over than 70 years old). Age standardized rate was used to achieve comparative statistics on cancer in Iran with those for other countries[17].

The expected coverage of cancer cases was calculated for medical universities of each province that is considered to be 113 per 100000 population. In the process of cancer incidence registry, all new diagnosed cancer cases by diagnostic centers are reported to the medical university. Reported data are entered to software which is made by ministry of health. Medical university of each province sends its temporary data bank to the ministry of health. Ministry of health after removing duplicates and coding the recorded cancers based on 10th revision of international coding of disease provides a permanent data bank of cancer cases and sends it back to medical university of each province. So medical universities have an observed number of cancer cases in addition to the expected rate. Percent of expected coverage for each province is calculated by dividing the observed number to the expected number of cancer cases.

The data were entered to the Bayesian model in the form of two vectors y1 and y2. Vector y1 = (y11, y21, ..., yr1)’ contained the data of the province that has an expected coverage less than 100% and vector y2 = (y12, y22, ..., yr2)’ contained the data of a neighboring province with more than 100% expected coverage. Subscript r is the indicator of covariate patterns that is made by age-sex group combinations. A Poisson distribution was considered for y1 and y2 that are count data[18,19]. An informative beta prior distribution was assumed for the misclassified parameter θ as the probability of registering a data in misclassified group; so θ~beta (a,b)[20-22]. In order to the expectation of beta distribution which is a/(a + b) get converged to the misclassified rate, prior values for b were selected based on the calculated expected coverage of the medical university with lower than 100% expected coverage and a was calculated with subtracting b from 100. Since misclassified parameter is unknown, a latent variable approach was employed to correct the misclassification effect[18,19]. The latent variable U was considered as the number of events from the first group that are incorrectly registered in the misclassified group with binomial distribution, i.e., Ui|θ,y1,y2~Binomial (yi2,Pi) that Pi=(λi1θ)/(λi1θ + λi2 ).

Finally by multiplying likelihood function in prior distribution, posterior distribution obtained in the following form; θ|Ui,y1,y2~Beta (∑iUi + a,∑iyi1 + b)[18,23-25]. Misclassified parameter was estimated by using a Gibbs sampling algorithm and averaging the generated posteriors. After estimating the misclassification rate between each two neighboring provinces, the rates of HCC incidence for each province were re-estimated and the trend of HCC were checked out during 2004 to 2008. Analyses were carried out using R software version 3.2.0.

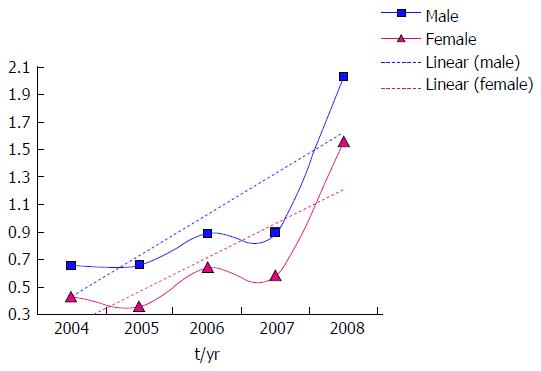

All registered HCC cases from 2004 to 2008 in Iran were included in the study. The ASR of HCC for female increases from 0.43 per 100000 population (103 cases) in 2004, to 1.56 per 100000 (376 cases) in 2008. Also ASR of HCC for male increases from 0.66 per 100000 population (180 cases) in 2004, to 2.03 per 100000 (574 cases) in 2008. The trend of HCC from 2004 to 2008 for Iranian male and female is shown in Figure 1.

Among 30 provinces of Iran, 21 ones were selected for correcting the misclassification error in registering HCC incidence in neighboring provinces based on their expected coverage percent of cancer cases. In the other nine provinces, the number of cancer cases was about the same as their expected number; so the cancer rates of them remained unchanged. Each time the data of two neighboring provinces that one of them had a more than 100% expected coverage and the other one had a less than 100% of its expected coverage were candidates for entering the Bayesian model for estimating the existed misclassification between them.

For example the reported percent of expected coverage of cancer incidence for East Azerbayjan which is a province with more medical facilities in north-west of Iran, was 123.6% in 2008. It means that East Azerbaijan province have covered 23.6% more cancer cases than its expectation, whereas the West Azerbaijan and Ardebil provinces that are in neighborhood of East Azerbaijan, have just covered 69% and 63% of their expected coverage of cancer incidence respectively; which is a clear indication of existence of misclassification error in registering cancer cases. The expected coverage for the provinces for years 2004 to 2008 are reported in Table 1. After implementing the Bayesian method it was estimated to be 0.13% misclassification between East Azerbaijan and Ardebil and 0.42% misclassification between East Azerbaijan and West Azerbaijan in 2008. The estimated misclassification rate among other provinces for years 2004 to 2008 are reported in Table 2. The rate of HCC incidence, before and after Bayesian correction of misclassification for years 2004 to 2008 are reported in Table 3.

| 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | |

| South khorasan | 30.30 | 45.16 | 41.02 | 41.40 | |

| Razavi khorasan | 106.50 | 106.50 | 101.81 | 117.54 | 143.74 |

| Tehran | 157.11 | 157.11 | 162.25 | 145.74 | 155.63 |

| Markazi | 43.35 | 43.35 | 53.07 | 57.46 | 69.60 |

| Sistan | 25.24 | 25.24 | 18.78 | 18.83 | 18.44 |

| Qom | 53.09 | 53.09 | 62.76 | 60.98 | 53.90 |

| Ghazvin | 65.07 | 65.07 | 71.44 | 72.84 | 66.30 |

| Khozesta | 61.09 | 61.09 | 62.68 | 69.81 | 101.19 |

| Ilam | 28.42 | 28.42 | 32.97 | 41.27 | 39.40 |

| Bushehr | 28.46 | 28.46 | 29.10 | 26.00 | 25.00 |

| Golestan | 50.65 | 50.65 | 58.61 | 58.20 | 50.80 |

| Mazandaran | 148.13 | 148.13 | 161.78 | 163.83 | 338.45 |

| North khorasan | 30.76 | 40.47 | 44.87 | 34.80 | |

| Chaharmahal | 40.67 | 40.67 | 34.39 | 40.76 | 37.00 |

| Isfahan | 111.51 | 111.51 | 114.09 | 116.93 | 106.98 |

| Kohgilouye | 23.90 | 23.90 | 29.00 | 29.60 | 25.10 |

| Hormozgan | 25.44 | 25.44 | 25.11 | 25.31 | 19.00 |

| Fars | 98.07 | 98.07 | 112.01 | 134.53 | 127.65 |

| Ardebil | 63.73 | 63.73 | 72.71 | 64.99 | 63.00 |

| East azarbaijan | 108.22 | 108.22 | 110.98 | 138.52 | 123.60 |

| West azarbaijan | 81.96 | 81.96 | 75.32 | 82.53 | 69.00 |

| Estimated misclassification rate | ||||||

| 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | ||

| Razavi khorasan | South khorasan | 0.2 | 0.51 | 0.44 | 0.58 | |

| Tehran | Markazi | 0.31 | 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.73 |

| Razavi khorasan | Sistan | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.65 | 0.41 | 0.51 |

| Tehran | Qom | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.28 | 0.65 |

| Tehran | Ghazvin | 0.2 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.74 |

| Khozesta | Ilam | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.42 | 0.5 | 0.73 |

| Khozesta | Bushehr | 0.38 | 0.4 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.72 |

| Mazandaran | Golestan | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.38 |

| Razavi khorasan | North khorasan | 0.16 | 0.43 | 0.34 | 0.42 | |

| Isfahan | Chaharmahal | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.23 |

| Isfahan | Kohgilouye | 0.18 | 0.43 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.16 |

| Fars | Hormozgan | 0.3 | 0.34 | 0.4 | 0.38 | 0.64 |

| East azarbaijan | Ardebil | 0.36 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.46 | 0.13 |

| East azarbaijan | West azarbaijan | 0.28 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.25 | 0.42 |

| ASR before Bayesian correction | ASR after Bayesian correction | |||||||||

| 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | |

| South khorasan | 0.50 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.83 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.12 | ||

| Razavi khorasan | 0.74 | 0.35 | 1.18 | 0.91 | 1.57 | 0.54 | 0.17 | 0.61 | 0.25 | 0.64 |

| Tehran | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.57 | 0.46 | 2.23 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.51 | 0.41 | 2.12 |

| Markazi | 0.37 | 0.25 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.61 | 0.49 | 0.66 |

| Sistan | 0.44 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.52 | 0.63 | 1.07 | 0.50 | 1.14 | 1.65 | 1.90 |

| Qom | 0.67 | 0.55 | 0.95 | 0.45 | 0.48 | 0.90 | 0.78 | 1.22 | 0.65 | 1.05 |

| Ghazvin | 0.62 | 0.47 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.80 | 0.65 | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.67 |

| Khozesta | 0.79 | 0.65 | 1.00 | 1.23 | 5.09 | 0.62 | 0.46 | 0.73 | 0.93 | 4.47 |

| Ilam | 1.13 | 0.86 | 0.54 | 0.49 | 0.78 | 1.88 | 1.50 | 1.23 | 1.07 | 2.23 |

| Bushehr | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 1.05 | 0.87 | 1.75 | 1.97 | 3.16 |

| Golestan | 0.76 | 0.40 | 0.83 | 0.55 | 0.66 | 0.88 | 0.62 | 1.13 | 0.68 | 1.14 |

| Mazandaran | 0.22 | 0.46 | 0.61 | 0.28 | 1.04 | 0.18 | 0.35 | 0.43 | 0.20 | 0.80 |

| North khorasan | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.76 | 0.86 | 0.94 | 1.28 | 1.34 | 1.89 | ||

| Chaharmahal | 0.84 | 1.13 | 1.02 | 0.52 | 1.01 | 1.17 | 1.57 | 1.55 | 1.01 | 1.62 |

| Isfahan | 0.41 | 0.61 | 0.64 | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.27 | 0.40 | 0.44 | 0.68 | 0.52 |

| Kohgilouye | 0.39 | 0.32 | 1.15 | 1.36 | 1.54 | 0.68 | 0.90 | 1.78 | 2.18 | 2.51 |

| Hormozgan | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.51 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 1.78 | 1.70 | 2.23 |

| Fars | 0.30 | 0.35 | 1.12 | 0.80 | 2.21 | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.67 | 0.54 | 1.56 |

| Ardebil | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 2.20 | 0.74 | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.69 | 2.65 |

| East azarbaijan | 0.69 | 0.30 | 0.19 | 0.92 | 0.97 | 0.44 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.57 | 0.61 |

| West azarbaijan | 0.64 | 0.55 | 0.91 | 0.98 | 0.53 | 0.86 | 0.64 | 0.97 | 1.27 | 0.84 |

There was a non-ignorable misclassification in registering cancer incidence between neighboring provinces in Iran. An increase is observed in trend of HCC during 2004 to 2008. The rate of HCC is even gets higher in some provinces after correcting for misclassification. Higher rates of estimated misclassifications are belonging to provinces with lower facilities like Hormozgan, Bushehr, Ilam, Qom, Markazi, Qazvin, Sistan and South Khorasan. Meanwhile it seems that misclassification rate is increasing during the period under study. It shows that not enough attention is paid to equip low-facilitate provinces.

The incidence of this cancer in many countries such as the United States, Central America and Europe is on the rise[7]. The findings of a study on incidence of HCC in Iran, showed that the incidence of this cancer is increasing in the country, especially in males and higher age groups[1]. A study on HCC indicated that little is known about the incidence of HCC in Iran, particularly in southeast of the country. Some provinces such as Ardebil, Guilan, Kerman, Fars, Razavi Khorasan, and most notably Tehran as the capital of Iran, have a low but significantly higher incidence proportional to other provinces[26]. It is also indicates the presence of misclassification error between neighboring provinces that are expected to have similar incidence rates of cancer.

Knowledge of geographic pattern of diseases is useful to identify the influencing factors on disease incidence and planning for disease control and prevention[27,28]. When a cluster with high incidence is not occurred by chance, this question comes to mind that what could be the underlying causal mechanism. It is natural to initially get focused on risk factors of the disease[29]. But major differences in incidence rate of HCC in neighboring provinces that are almost identical in exposure with risk factors, is justifiable with existence of misclassification error in registering patient permanent residence, that are diagnosed and registered in facilitate provinces of the country.

In conclusion there is misclassification error in cancer registry system despite international efforts to standardize cancer incidence data collection processes and elimination of deficiencies in personal and demographic information, especially in developing countries such as Iran[30]. So the true incidence rate of HCC is higher than the reported rate in some provinces and consequently lower in some other provinces. Since cancer registry data is used by health policy makers to allocate the facilities and resources to different provinces. To help for making the right decisions, it is necessary to correct for misclassification in cancer incidence between provinces. Otherwise again fewer resources will be assigned to low facility provinces based on the low incidence rate, while they are in need of more healthcare facilities and the true cancer incidence rate is more than taught in that provinces.

Iran is located in Middle East, a region where majority of HCC cases presents with intermediate or advanced stages of the disease[4,31]. In most Asian countries, early detection and treatment services are limited. There are many people who have no health insurance and many of them are too poor to go for screening tests or medical treatments. Therefore, it is important for the health organizations and governments in each country to recognize these groups in order to reduce the incidence and mortality of cancers[5].

The dramatic increase in the forecasted number of deaths due to HCC in the United States is a warning to the research and healthcare systems since it projected to be one of the top three cancer killers in 2030[32-34].

So whereas deaths from liver are projected to increase, changes in treatment and prevention strategies, using screening tests, vaccination, and informing about risk factors and early symptoms of HCC can alter both the incidence and death rates. It requires an unisonant effort by search and health care organizations now for a substantial change in the future[7,9,34]. Also employing and training more motivated and educated staff in all sectors of cancer registry program in order to complete the cancer case registry forms accurately and remit them to the appropriate center, Enhancing hardware and software resources, expert researchers in medicine, biostatistics and computer science are needed to qualify the cancer registry program and increasing its completeness; specially in address-related information[35,36].

In the absence of valid data, statistical methods are good alternatives for correcting the existed errors in data. Of course it should be noted that there is always some uncertainty as a potential weakness in statistical models and the statistical model which was used in this study is also not an exception. Thus a small cluster of HCC cases could be misattributed as patients registering in a neighboring province. But the low cost, high speed and efficiency of this model can compensate small errors.

Some patients from deprived provinces prefer to get medical treatment in their neighboring provinces with more medical facilities without mentioning their permanent residence. It makes misclassification error in cancer registry data. Consequently health policy makers who use cancer registry data for resource allocation and cancer control programs will make mistakes in their decisions. The aim of this study is to investigate the trend of hepatocellular carcinoma incidence after correcting for misclassification between neighboring provinces by means of a Bayesian method.

Knowing about geographic spread of cancers is so important for identification the risk factors of cancers for control and prevention purposes. There is misclassification in patient’s permanent residence in Iran’s cancer registry data that leads to under-estimating the rate of cancer in some provinces and consequently over-estimating in other provinces. While those cancer rates are used in spatial analysis to determine the high risk areas, the existence of misclassification error is usually ignored. The hotspot of this study is accounting and correcting for misclassification in registering cancer incidence using the Bayesian method.

By using the Bayesian method for estimating the rate of misclassification, that’s enough to have prior information about the misclassification rate and there is no need for validating data to explore the misclassification rate which is costly and time consuming. Bayesian method for correcting the misclassification is a faster and more cost effective method in comparison to data validation which in many cases is not achievable.

Cancer incidence rates are used for allocating medical resources to different provinces. So to have more accurate estimates from the rates of cancer incidence in each province misclassification error in registering patient’s permanent residence should be corrected. Consequently better planning and decisions will be made for interventions for cancer control and prevention.

Bayesian method is a statistical method that assigns a prior distribution to parameters or events, according to expert’s idea or previous knowledge from previous studies and updates those distributions with combining prior knowledge by observed data by using Bayes’ theorem. Misclassification is one of the measurement error which is defined as disagreement between the observed value and the true value in categorical data.

This is a very interesting study from Iran aimed at estimating the rate of regional misclassification in registering the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in cancer registry system using a Bayesian method. The study is original and very well written. The statistical analysis is well done. The results are consistent.

| 1. | Mirzaei M, Ghoncheh M, Pournamdar Z, Soheilipour F, Salehiniya H. Incidence and Trend of Liver Cancer in Iran. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2016;26:306-309. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray . GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC Cancer Base No. 11 [Internet]. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013; Available from: http://publications.iarc.fr/Databases/IarcCancerbases/Globocan-2012-Estimated-Cancer-Incidence-MortalityAnd-Prevalence-Worldwide-In-2012-V1-0-2012. |

| 3. | Fallah MA. Cancer Incidence in Five Provinces of Iran: Ardebil, Gilan, Mazandaran, Golestan and Kerman, 1996-20000. Tampere University press 2007. . [PubMed] |

| 4. | Pourhoseingholi MA, Fazeli Z, Zali MR, Alavian SM. Burden of hepatocellular carcinoma in Iran; Bayesian projection and trend analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11:859-862. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Pourhoseingholi MA, Vahedi M, Baghestani AR. Burden of gastrointestinal cancer in Asia; an overview. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2015;8:19-27. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Merat S, Malekzadeh R, Rezvan H. Hepatitis B in Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2000;3:192-201. |

| 7. | Mahdavi S, Amoori N, Salehiniya H, Enayatrad M. Epidemiology and trends in mortality from liver cancer in Iran. IJER. 2015;2:239-240. |

| 8. | Alavian SM, Fallahian F, Lankarani KB. The changing epidemiology of viral hepatitis B in Iran. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2007;16:403-406. [PubMed] |

| 9. | American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2016. Atlanta, Ga: American Cancer Society; 2016; . |

| 10. | Nordenstedt H, White DL, El-Serag HB. The changing pattern of epidemiology in hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42 Suppl 3:S206-S214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 367] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Gomaa AI, Khan SA, Toledano MB, Waked I, Taylor-Robinson SD. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology, risk factors and pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4300-4308. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Hajizadeh N, Pourhoseingholi MA, Baghestani A, Abadi A. Under-estimation and over-estimation in gastric cancer incidence registry, Bayesian analysis for selected provinces. Arvand J Health MedSci. 2016;1:90-94. |

| 13. | Hajizadeh N, Pourhoseingholi MA, Baghestani AR, Abadi A, Ghoreshi B. Years of life lost due to gastric cancer is increased after Bayesian correcting for misclassification in Iranian population. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2016;9:295-300. |

| 14. | Aghajani H, Etemad K, Gouya M, Ramezani R, Modirian M, Nadali F. Iranian Annual of National Cancer Registration Report 2008-2009. 1st ed. Tehran: Tandis 2011; 25-120. |

| 15. | Lyles RH. A note on estimating crude odds ratios in case-control studies with differentially misclassified exposure. Biometrics. 2002;58:1034-1036; discussion 1036-1037. [PubMed] |

| 16. | McInturff P, Johnson WO, Cowling D, Gardner IA. Modelling risk when binary outcomes are subject to error. Stat Med. 2004;23:1095-1109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ahmad OB, Boschi-Pinto C, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, Lozano R, Inoue M. Age standardization of rates: a new WHO standard. Geneva: WHO 2001; 9. |

| 18. | Stamey JD, Young DM, Seaman JW. A Bayesian approach to adjust for diagnostic misclassification between two mortality causes in Poisson regression. Stat Med. 2008;27:2440-2452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pourhoseingholi MA, Faghihzadeh S, Hajizadeh E, Abadi A, Zali MR. Bayesian estimation of colorectal cancer mortality in the presence of misclassification in Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2009;10:691-694. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Pourhoseingholi MA, Abadi A, Faghihzadeh S, Pourhoseingholi A, Vahedi M, Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Safaee A, Zali MR. Bayesian analysis of esophageal cancer mortality in the presence of misclassification. Italian J Public Health. 2012;8:342-347. |

| 21. | Paulino CD, Soares P, Neuhaus J. Binomial regression with misclassification. Biometrics. 2003;59:670-675. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Paulino CD, Silva G, Achcar JA. Bayesian analysis of correlated misclassified binary data. Computational statistics and data analysis. 2005;1120-1131. |

| 23. | Liu Y, Johnson WO, Gold EB, Lasley BL. Bayesian analysis of risk factors for anovulation. Stat Med. 2004;23:1901-1919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pourhoseingholi MA. Bayesian adjustment for misclassification in cancer registry data. Translational Gastrointestinal Cancer. 2014;3:144-148. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 25. | Sharifian A, Pourhoseingholi MA, Baghestani A, Hajizadeh N, Gholizadeh S. Burden of gastrointestinal cancers and problem of the incomplete information; how to make up the data? Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2016;9:12-17. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Blum HE. Hepatocellular carcinoma: therapy and prevention. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:7391-7400. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Mehrabani D, Tabei SZ, Heydari ST, Shamsina SJ, Shokrpour N, Amini M, Masoumi SJ, Julaee H, Farahmand M, Manafi A. Cancer occurrence in Fars Province, Southern Iran. Iranian Red Crescent Med J. 2008;10:314-322. |

| 28. | Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2137-2150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2655] [Cited by in RCA: 2655] [Article Influence: 132.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 29. | Mohebbi M, Mahmoodi M, Wolfe R, Nourijelyani K, Mohammad K, Zeraati H, Fotouhi A. Geographical spread of gastrointestinal tract cancer incidence in the Caspian Sea region of Iran: spatial analysis of cancer registry data. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hajizadeh N, Pourhoseingholi MA, Baghestani A, Abadi A, Zali MR. Under-estimation and over-estimation in gastric cancer incidence registry in Khorasan provinces, Iran. J Cell Immunother. 2015;1:11-12. |

| 31. | Siddique I, El-Naga HA, Memon A, Thalib L, Hasan F, Al-Nakib B. CLIP score as a prognostic indicator for hepatocellular carcinoma: experience with patients in the Middle East. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:675-680. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Chuang SC, La Vecchia C, Boffetta P. Liver cancer: descriptive epidemiology and risk factors other than HBV and HCV infection. Cancer Lett. 2009;286:9-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Jemal A, Center MM, DeSantis C, Ward EM. Global patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1893-1907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, Matrisian LM. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2913-2921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5379] [Cited by in RCA: 5354] [Article Influence: 446.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Teppo L, Pukkala E, Lehtonen M. Data quality and quality control of a population-based cancer registry. Experience in Finland. Acta Oncol. 1994;33:365-369. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Merrill D. Training and retaining staff in the cancer registry. J Registry Manag. 2010;37:67-68. [PubMed] |

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Iran

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Lai Q, Mihaila R, Julie NL S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D