Peer-review started: July 14, 2016

First decision: September 12, 2016

Revised: September 25, 2016

Accepted: November 21, 2016

Article in press: November 22, 2016

Published online: January 8, 2017

Processing time: 180 Days and 16.7 Hours

To evaluate the therapeutic effects of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) on autoimmune hepatitis (AIH).

A total 136 patients who were diagnosed with AIH were included in our study. All of the patients underwent a liver biopsy, and had at least a probable diagnosis on the basis of either the revised scoring system or the simplified scores. Initial treatment included UDCA monotherapy (Group U, n = 48) and prednisolone (PSL) monotherapy (Group P, n = 88). Group U was further classified into two subgroups according to the effect of UDCA: Patients who had achieved remission induction with UDCA monotherapy and showed no sign of relapse (Subgroup U1, n = 34) and patients who additionally received PSL during follow-up (Subgroup U2, n = 14). We compared the clinical and histological findings between each groups, and investigated factors contributing to the response to UDCA monotherapy.

In Group U, 34 patients (71%) achieved and maintained remission over 49 (range: 8-90) mo (Subgroup U1) and 14 patients (29%) additionally received PSL (Subgroup U2) during follow-up. Two patients in Subgroup U2 achieved remission induction once but additionally required PSL administration because of relapse (15 and 35 mo after the start of treatment). The remaining 12 patients in Subgroup U2 failed to achieve remission induction during follow-up, and PSL was added during 7 (range: 2-18) mo. Compared with Subgroup U2, Subgroup U1 had significantly lower alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels at onset (124 IU/L vs 262 IU/L, P = 0.023) and a significantly higher proportion of patients with mild inflammation (A1) on histological examination (70.6% vs 35.7%, P = 0.025). When multivariate analysis was performed to identify factors contributing to the response to UDCA monotherapy, only a serum ALT level of 200 IU/L or lower was found to be associated with a significant difference (P = 0.013).

To prevent adverse events related to corticosteroids, UDCA monotherapy for AIH needs to be considered in patients with a serum ALT level of 200 IU/L or lower.

Core tip: Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is generally responsive to immunosuppressive treatment, and corticosteroids are commonly used for the initial and maintenance treatments. However, corticosteroid treatment must be discontinued in some patients because of several side effects. This study aimed to evaluate the therapeutic effects of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), which has high tolerability and no severe side effects, on AIH. Our results suggest that to prevent adverse events related to corticosteroids, treatment with UDCA alone for AIH needs to be considered in selected patients, especially those with an alanine aminotransferase level of 200 IU/L or lower. This utility of UDCA must be confirmed in a prospective study.

- Citation: Torisu Y, Nakano M, Takano K, Nakagawa R, Saeki C, Hokari A, Ishikawa T, Saruta M, Zeniya M. Clinical usefulness of ursodeoxycholic acid for Japanese patients with autoimmune hepatitis. World J Hepatol 2017; 9(1): 57-63

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v9/i1/57.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v9.i1.57

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is an unresolving progressive liver disease that affects females preferentially and is characterized by interface hepatitis, hyper-gammaglobulinemia, circulating autoantibodies, and a favorable response to immunosuppression. The aim of treatment in AIH is to obtain complete remission of the disease and to prevent further progression of liver disease, which generally requires permanent maintenance therapy. Corticosteroids have been widely used as the first choice drug treatment of AIH[1,2]. However, long-term treatment with a generous corticosteroid dosage may induce predictable side effects, such as cosmetic changes (facial rounding, dorsal hump formation, striae, weight gain, acne, alopecia, and facial hirsutism) or even more dreadful complications, such as osteopenia, brittle diabetes, psychosis, pancreatitis, opportunistic infections, labile hypertension, and malignancy[3-7]. Consequently, corticosteroid treatment must be discontinued in 13% of patients. Of those withdrawn from therapy, most have intolerable cosmetic changes or obesity (47%), osteoporosis with vertebral compression (27%), and/or difficult-to-control diabetes (20%)[4,8]. Because AIH predominantly affects middle-aged women, the presence of cosmetic issues is one of the key factors for maintaining drug compliance. Cosmetic issues may lead to emotional problems that result in treatment failure and a poor prognosis. Thus, a strategy to reduce the adverse effects of corticosteroid treatment is needed.

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) has been widely used as the first choice for treating primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) and has been established as clinically useful[9-11]. No severe side effects have been reported during UDCA therapy for PBC[12]. Although there are reports that UDCA is also useful for treating similar autoimmune liver diseases, its clinical value has not as yet been established[13-15]. In this study, patients with a confirmed diagnosis of AIH who started treatment with UDCA alone were analyzed, and the results are reported.

The present study included 136 patients who were diagnosed with AIH between 1975 and 2011 at the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, The Jikei University Hospital (Tokyo, Japan). All of the patients had at least a probable diagnosis on the basis of either the revised scoring system, as proposed by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group in 1999[16], or the simplified scores[17]. All of the patients underwent a liver biopsy. In this study, patients with no histological fibrosis (F0) were excluded. Chronic viral hepatitis B and C were excluded by serological testing in all of the patients. Patients with an overlapping syndrome or a coexistent liver disease (e.g., primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, or alcohol-induced liver injury) were also excluded by medical history, serological data and histological finding. So, patients with positive antimitochondrial antibody were excluded. Of the 136 patients, 48 received UDCA (Group U) after diagnosis, and the remaining 88 received prednisolone (PSL) (Group P). Furthermore, Group U was divided into the following subgroups: Subgroup A, consisting of 33 patients with a serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 200 IU/L or lower at the start of treatment; Subgroup B, consisting of 29 patients in whom histological activity on liver biopsy before the start of treatment was determined to be A1 on the basis of the classification of Desmet et al[18]; Subgroup C, consisting of 24 patients who were included in both Subgroups A and B; Subgroup D consisting of 15 patients with a serum ALT level of 200 IU/L or higher at the start of treatment; Subgroup E consisting of 19 patients in whom histological activity was A2 or A3 before the start of treatment; and Subgroup F consisting of 10 patients who were included in both Subgroups D and E. The clinical characteristics of the study subjects are presented in Table 1.

| Group U (n = 48) | Group P (n = 88) | P | |

| Age (yr) | 45 (17-74) | 51 (15-78) | ns |

| Sex (female) | 45 (93.8%) | 65 (73.9%) | < 0.01 |

| Acute presentation | 5 (10.4%) | 31 (36.5%) | < 0.01 |

| Laboratory data | |||

| AST (IU/L) | 104 (46-1234) | 303 (31-2215) | < 0.001 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 149 (52-1000) | 431 (38-2801) | < 0.001 |

| T.Bil (mg/dL) | 0.8 (0.3-18) | 1.3 (0.4-19.3) | < 0.05 |

| ALP (U/L) | 300 (144-1184) | 369 (145-4420) | ns |

| γ-GTP (U/L) | 82 (13-875) | 183 (12-1256) | < 0.05 |

| IgG (mg/dL) | 1954 (1096-3793) | 2336 (1051-5776) | < 0.01 |

| ANA (≥ 1 : 40) | 46 (95.8%) | 83 (94.3%) | ns |

| SMA (≥ 1 : 40) | 11/23 (47.8%) | 35/45 (77.8%) | < 0.05 |

| HLA DR4 | 6/16 (37.5%) | 33/57 (57.9%) | ns |

| Histological finding | |||

| Grading | |||

| A1 | 29 (60.4%) | 25 (28.4%) | < 0.01 |

| A2 | 18 (37.5%) | 44 (50%) | |

| A3 | 1 (2.1%) | 19 (21.6%) | |

| Staging | |||

| F1 | 35 (72.9%) | 43 (48.9%) | < 0.05 |

| F2 | 6 (12.5%) | 28 (31.8%) | |

| F3 | 6 (12.5%) | 10 (11.4%) | |

| F4 | 1 (2.1%) | 7 (8.0%) | |

| AIH score | |||

| Revised score | 15 (10-20) | 16 (7-23) | ns |

| Simplified score | 6 (4-8) | 6 (3-8) | ns |

In each group and subgroup described above, subsequent clinical courses, changes in treatment, and histological findings at the time of diagnosis were evaluated. Moreover, Group U was divided into Subgroup U1, consisting of patients who had achieved remission induction with UDCA monotherapy and showed no sign of relapse, and Subgroup U2, consisting of patients who additionally received PSL during follow-up. Laboratory test results and histopathological findings at the time of diagnosis were compared between Subgroups U1 and U2 (Table 2).

| Subgroup U11(n = 34) | Subgroup U22(n = 14) | P | |

| Age (yr) | 42 (17-74) | 48 (21-66) | ns |

| Sex (female) | 33 (97.1%) | 12 (85.7%) | ns |

| Acute presentation | 4 (11.8%) | 1 (7.1%) | ns |

| Laboratory data | |||

| AST (IU/L) | 93 (46-505) | 144 (50-1234) | 0.024 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 124 (52-742) | 262 (65-1000) | 0.023 |

| T.Bil (mg/dL) | 0.7 (0.3-18) | 1.0 (0.3-2) | ns |

| ALP (U/L) | 300 (144-1184) | 300 (168-924) | ns |

| γ-GTP (U/L) | 86 (16-875) | 67 (13-405) | ns |

| IgG (mg/dL) | 1959 (1096-3800) | 1960 (1476-3793) | ns |

| ANA (≥ 1 : 40) | 32 (94.1%) | 14 (100%) | ns |

| SMA (≥ 1 : 40) | 8/17 (47.1%) | 3/6 (50%) | ns |

| HLA DR4 | 4/11 (36.4%) | 2/5 (40%) | ns |

| Histological finding | |||

| Grading | |||

| A1 | 24 (70.6%) | 5 (35.7%) | 0.025 |

| A2 | 10 (29.4%) | 8 (57.1%) | |

| A3 | 0 (0%) | 1 (7.1%) | |

| Staging | |||

| F1 | 25 (73.5%) | 10 (71.4%) | ns |

| F2 | 4 (11.8%) | 2 (14.3%) | |

| F3 | 5 (14.7%) | 1 (7.1%) | |

| F4 | 0 (0%) | 1 (7.1%) | |

| AIH score | |||

| Revised score | 15 (10-19) | 17 (12-20) | ns |

| Simplified score | 6 (4-8) | 6 (6-7) | ns |

This study complied with the standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and the current ethical guidelines, and was approved by the institutional ethics board. Written, informed consent for participation in this study was not obtained from the patients, because this study did not report on a clinical trial and the data were retrospective in nature and analyzed anonymously.

PSL was used as the standard initial treatment. Taking into account body weight, the initial dose was set between 30 and 40 mg/d, with subsequent reduction after improvement in liver function had been confirmed.

In mild clinical cases with both histological low-grade inflammatory activity and adequate residual capacity of liver function, the initial treatment was UDCA alone. The initial dose of UDCA was set at 600 mg/d (10-13 mg/kg per day) in accordance with Japanese guideline for the treatment of PBC. The dosage was neither increased nor decreased during the treatment period. PSL was also administered, as described above, when an incomplete response to UDCA monotherapy or relapse was observed.

Each patient underwent a comprehensive clinical review and physical examination at each follow-up visit. Conventional laboratory blood tests were performed every 1-3 mo.

Remission was defined as a normalization of serum ALT levels after the start of treatment. The judgement of remission for UDCA monotherapy was carried out within at least 18 mo after initiation of therapy. Relapse was defined as an increase in serum ALT levels to more than twice the upper normal limit following the normalization of serum ALT levels with medical treatment.

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistical program (release 16.0.1 J, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Continuous variables are expressed as medians and ranges. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to evaluate differences in continuous variables between two groups. Dichotomous variables were compared by Pearson’s χ2 test. Multivariate analyses by logistic regression were used to identify independent factors contributing to the response to UDCA monotherapy. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

As the initial treatment, of the 136 patients, 48 received UDCA monotherapy (Group U) and 88 received PSL monotherapy (Group P). There were no differences between Groups U and P in age, serum levels of alkaline phosphatase, the frequencies of positivity for antinuclear antibody or human leukocyte antigen DR4, and scores derived from either the old or the new scoring system. However, compared with Group P, Group U had significantly lower serum levels of aspartate transaminase (AST) (104 IU/L vs 303 IU/L, P < 0.001), ALT (149 IU/L vs 431 IU/L, P < 0.001), total bilirubin (0.8 mg/dL vs 1.3 mg/dL, P < 0.05), γ-glutamyltransferase (82 U/L vs 182 U/L, P < 0.05), and immunoglobulin G (1954 mg/dL vs 2336 mg/dL, P < 0.01), and lower frequencies of male sex, acute presentation, and positivity for smooth muscle antibody at the onset. Additionally, Group U had a significantly higher proportion of patients with mild inflammation and fibrosis (A1 and F1) on histological examination (28.4% vs 60.4%, P < 0.01, and 48.9% vs 72.9%, P < 0.05) (Table 1). Cumulative incidence of the normalization of serum ALT levels was 80% in Group P.

The follow-up durations were 49 (range: 8-156) mo in Group U. In Group U, 34 patients (71%) achieved and maintained remission over 49 (range = 8-90) mo (Subgroup U1), and 14 patients (29%) additionally received PSL during follow-up (Subgroup U2). Two patients in Subgroup U2 achieved remission induction once but additionally required PSL administration because of relapse (15 and 35 mo after the start of treatment). The remaining 12 patients in Subgroup U2 failed to achieve remission induction during follow-up, and PSL was added during 7 (range: 2-18) mo.

The rate of numbers was 73% in Subgroup U1 and 27% in Subgroup U2. Compared with Subgroup U2, Subgroup U1 had significantly lower ALT levels at onset (124 IU/L vs 262 IU/L, P = 0.023) and a significantly higher proportion of patients with mild inflammation (A1) on histological examination (70.6% vs 35.7%, P = 0.025) (Table 2). However, there were no differences between Subgroups U1 and U2 in other clinical features, as shown in Table 2.

When multivariate analysis was performed to identify factors contributing to the response to UDCA monotherapy, a serum ALT level of 200 IU/L or lower was found to be associated with a significant difference (Table 3).

| Factor | Category | Odds ratio (95%CI) | P |

| ALT (IU/L) | > 200 | 1 | |

| ≤ 200 | 10.8 (1.64-71.0) | 0.013 | |

| Age | > 50 | 1 | |

| ≤ 50 | 1.16 (0.21-6.38) | 0.86 | |

| IgG | > 2000 | 1 | |

| ≤ 2000 | 0.65 (0.10-4.32) | 0.66 | |

| Acute presentation | No | 1 | |

| Yes | 4.13 (0.15-110.5) | 0.4 | |

| Histological Grading | A2 or A3 | 1 | |

| A1 | 0.76 (0.10-5.88) | 0.8 | |

| Histological Staging | F2 or F3 or F4 | 1 | |

| F1 | 0.41 (0.04-4.44) | 0.46 | |

| AIH score | > 15 | 1 | |

| (International diagnostic criteria) | ≤ 15 | 2.66 (0.43-16.48) | 0.29 |

| AIH score | > 6 | 1 | |

| (Simplified criteria) | ≤ 6 | 5.46 (0.37-81.3) | 0.22 |

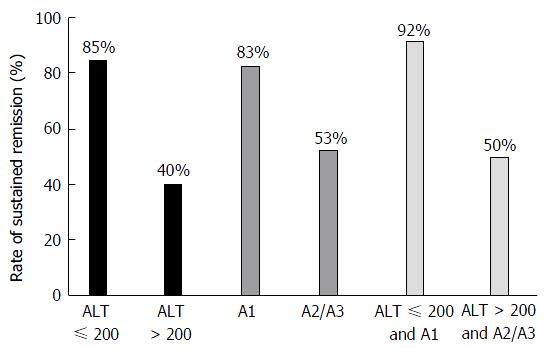

On subgroup analysis, remission was induced and maintained by UDCA in 85%, 83% and 92% of patients in Subgroups A, B, and C, respectively. In these subgroups, high rates of remission induction and successful maintenance were achieved by UDCA. On the other hand, the rates of remission induction and successful maintenance in Subgroups D, E and F were low, at 40%, 53%, and 50%, respectively (Figure 1).

UDCA has been widely used as the first choice drug for the treatment of PBC[9-11]. This is because of its efficacy for cholestasis, exerted through its choleretic action which is well understood[19]. In addition to its choleretic action, UDCA reportedly has a protective action on hepatocytes and an immunomodulatory action[20]. In fact, it has also been reported that the administration of UDCA reduces elevated serum immunoglobulin levels in patients with PBC, which is one of the clinical characteristics of PBC[9,21]. In vitro studies have also shown that UDCA inhibits immunoglobulin production by peripheral lymphocytes in a concentration-dependent manner[22]. Although the UDCA level required to inhibit immunoglobulin production is approximately 10 times the blood concentration after administration of UDCA at routine doses[22], similarly high levels apparently exist in hepatocytes secreting bile, in other words, in the liver. Thus, UDCA may exert a liver-specific immunosuppressive action. This indicates that UDCA can be administered to achieve immunosuppression in patients with AIH. Miyake et al[13] demonstrated in a small-scale study that UDCA is effective for AIH. Moreover, the administration of UDCA has also been shown to allow corticosteroid doses to be tapered[14].

In this study, 71% of the UDCA group achieved and maintained the normalization of serum ALT levels with UDCA monotherapy. Especially, the present study also identified that in 85% of the patients with ALT levels of 200 IU/L or lower at the start of treatment, AIH remission could be induced and maintained by UDCA monotherapy. So, UDCA monotherapy will be effective in some Japanese AIH patients. However, in this study, patients treated with UDCA monotherapy had lower serum ALT levels and milder histological activity and fibrosis at presentation than those treated with PSL as shown in Table 1. Hence, it is necessary to consider that usefulness of UDCA was presented in mild AIH group. In the future, utility of UDCA must be confirmed in a prospective study.

On the other hand, among these mild AIH patients, the proportion indicated for UDCA monotherapy was low. On the bases of this finding, the patients in Group U can be considered to have no indications for treatment. In fact, 10-year survival in untreated patients with mild disease was reported to be 67%-90%[23,24], and in an uncontrolled study, untreated asymptomatic patients had similar survival to those receiving immunosuppression[25]. However, it also has to be acknowledged that untreated AIH has a fluctuating, unpredictable disease behavior, and a substantial proportion of asymptomatic patients become symptomatic during the course of their disease follow-up[25,26], and progression towards end-stage liver disease with liver failure and development of HCC is possible[24]. Muratori et al[27] also reported that patients with asymptomatic vs symptomatic AIH have similar courses of disease progression and responses to immunosuppressive agents, and should therefore receive the same treatment. Additionally, to exclude patients with transient liver damage that may not have required treatment, patients with no histological fibrosis (F0) were not enrolled in the present study.

According to the AIH Guidelines issued by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases in 2010, no treatment is needed for patients with AST and ALT levels close to or below the standard levels[1]. The patients included in the present study did not meet these criteria, but largely met the indications for treatment. While the efficacy of corticosteroids for the treatment of AIH has been established, treatment with corticosteroids is currently the first choice only in patients with appropriate indications[1,2]. However, corticosteroids are associated with adverse events, such that there is often reluctance to administer these drugs. In patients with AIH in Japan, the age at onset and diagnosis has been increasing annually[28]. Particularly in elderly women, many of whom are postmenopausal, there is actually considerable concern regarding osteoporosis. Moreover, in the treatment of AIH, prevention of relapse is the most important issue, and maintenance therapy is thus important. However, because many patients are women, drug compliance can actually be poor due to cosmetic issues. In addition, it has also been pointed out that the incidence of other adverse events is high in elderly patients. The present study subjects had an age distribution between 17 and 74 years, demonstrating that elderly patients with AIH associated with mild liver disorders could be treated with UDCA. Moreover, when the therapeutic effects of UDCA become inadequate, treatment can be continued by switching to corticosteroids, as shown in the present study. Furthermore, treatment with UDCA also has the benefit of eventually allowing the corticosteroid dose to be tapered[14]. A recent nationwide survey on AIH in Japan showed that UDCA monotherapy is administered as the initial treatment in 20% of patients[28], so it is reasonable to assume that the treatment of AIH with UDCA is becoming clinically established. While Czaja et al[15] found UDCA to be effective in a double-blind study, it is important to define criteria for UDCA treatment indications, as in the present study. Although the present study had a retrospective design, the results allow the conclusion to be drawn that UDCA use may be considered in patients with a serum ALT level of 200 IU/L at the time of diagnosis, especially in those who are elderly. Prospective studies on the long-term outcomes of patients receiving UDCA monotherapy are needed.

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is an unresolving progressive liver disease that affects females preferentially and is characterized by interface hepatitis, hyper-gammaglobulinemia, circulating autoantibodies, and a favorable response to immunosuppression. The aim of treatment in AIH is to obtain complete remission of the disease and to prevent further progression of liver disease, which generally requires permanent maintenance therapy. Corticosteroids have been widely used as the first choice drug treatment of AIH. However, long-term treatment with a generous corticosteroid dosage may induce side effects. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) has been widely used as the first choice for treating primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) and has been established as clinically useful. No severe side effects have been reported during UDCA therapy for PBC. Although there are reports that UDCA is also useful for treating similar autoimmune liver diseases, its clinical value has not as yet been established. In this study, patients with a confirmed diagnosis of AIH who started treatment with UDCA alone were analyzed.

There are few reports that UDCA monotherapy is effective for treating AIH. Moreover, the administration of UDCA has also been shown to allow corticosteroid doses to be tapered. However, its clinical value has not as yet been established.

Few prior reports showed that UDCA is effective in some AIH patients. However, there is no report which showed independent predictive factors associated with normalized ALT and sustained remission of UDCA monotherapy in AIH patients. The present study showed that ALT levels of 200 IU/L or lower associated with to response to UDCA monotherapy. The results of the authors’ study contribute to predict the therapeutic effect of UDCA for patients with AIH.

This study suggests that that to prevent adverse events related to corticosteroids, treatment with UDCA alone for AIH needs to be considered in selected patients, especially those with an ALT level of 200 IU/L or lower.

UDCA: One of the secondary bile acids, which are metabolic byproducts of intestinal bacteria. It has been widely used as the first choice drug for the treatment of PBC. This is because of its efficacy for cholestasis, exerted through its choleretic action which is well understood. In addition to its choleretic action, UDCA reportedly has a protective action on hepatocytes and an immunomodulatory action.

This is a very interesting cut off point for future prospective studies to confirm these retrospective results.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Castiella A, Maroni L S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Mayo MJ. Management of autoimmune hepatitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2011;27:224-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2015;63:971-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 659] [Cited by in RCA: 884] [Article Influence: 80.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Summerskill WH, Korman MG, Ammon HV, Baggenstoss AH. Prednisone for chronic active liver disease: dose titration, standard dose, and combination with azathioprine compared. Gut. 1975;16:876-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Czaja AJ. Safety issues in the management of autoimmune hepatitis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2008;7:319-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Uribe M, Go VL, Kluge D. Prednisone for chronic active hepatitis: pharmacokinetics and serum binding in patients with chronic active hepatitis and steroid major side effects. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1984;6:331-335. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Lebovics E, Schaffner F, Klion FM, Simon C. Autoimmune chronic active hepatitis in postmenopausal women. Dig Dis Sci. 1985;30:824-828. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Wright SH, Czaja AJ, Katz RS, Soloway RD. Systemic mycosis complicating high dose corticosteroid treatment of chronic active liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1980;74:428-432. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Czaja AJ, Davis GL, Ludwig J, Taswell HF. Complete resolution of inflammatory activity following corticosteroid treatment of HBsAg-negative chronic active hepatitis. Hepatology. 1984;4:622-627. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Poupon RE, Balkau B, Eschwège E, Poupon R. A multicenter, controlled trial of ursodiol for the treatment of primary biliary cirrhosis. UDCA-PBC Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1548-1554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 570] [Cited by in RCA: 559] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Poupon RE, Lindor KD, Cauch-Dudek K, Dickson ER, Poupon R, Heathcote EJ. Combined analysis of randomized controlled trials of ursodeoxycholic acid in primary biliary cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:884-890. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Shi J, Wu C, Lin Y, Chen YX, Zhu L, Xie WF. Long-term effects of mid-dose ursodeoxycholic acid in primary biliary cirrhosis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1529-1538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lindor KD, Dickson ER, Baldus WP, Jorgensen RA, Ludwig J, Murtaugh PA, Harrison JM, Wiesner RH, Anderson ML, Lange SM. Ursodeoxycholic acid in the treatment of primary biliary cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1284-1290. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Miyake Y, Iwasaki Y, Kobashi H, Yasunaka T, Ikeda F, Takaki A, Okamoto R, Takaguchi K, Ikeda H, Makino Y. Efficacy of ursodeoxycholic acid for Japanese patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatol Int. 2009;3:556-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Nakamura K, Yoneda M, Yokohama S, Tamori K, Sato Y, Aso K, Aoshima M, Hasegawa T, Makino I. Efficacy of ursodeoxycholic acid in Japanese patients with type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:490-495. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA, Lindor KD. Ursodeoxycholic acid as adjunctive therapy for problematic type 1 autoimmune hepatitis: a randomized placebo-controlled treatment trial. Hepatology. 1999;30:1381-1386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, Bianchi L, Burroughs AK, Cancado EL, Chapman RW, Cooksley WG, Czaja AJ, Desmet VJ. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:929-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2003] [Cited by in RCA: 2012] [Article Influence: 74.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, Parés A, Dalekos GN, Krawitt EL, Bittencourt PL, Porta G, Boberg KM, Hofer H. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:169-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1205] [Cited by in RCA: 1305] [Article Influence: 72.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Desmet VJ, Gerber M, Hoofnagle JH, Manns M, Scheuer PJ. Classification of chronic hepatitis: diagnosis, grading and staging. Hepatology. 1994;19:1513-1520. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Jazrawi RP, de Caestecker JS, Goggin PM, Britten AJ, Joseph AE, Maxwell JD, Northfield TC. Kinetics of hepatic bile acid handling in cholestatic liver disease: effect of ursodeoxycholic acid. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:134-142. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Lazaridis KN, Gores GJ, Lindor KD. Ursodeoxycholic acid ‘mechanisms of action and clinical use in hepatobiliary disorders’. J Hepatol. 2001;35:134-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kisand KE, Karvonen AL, Vuoristo M, Färkkilä M, Lehtola J, Inkovaara J, Kisand KV, Miettinen T, Krohn K, Uibo R. Ursodeoxycholic acid treatment lowers the serum level of antibodies against pyruvate dehydrogenase and influences their inhibitory capacity for the enzyme complex in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. J Mol Med (Berl). 1996;74:269-272. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Yoshikawa M, Tsujii T, Matsumura K, Yamao J, Matsumura Y, Kubo R, Fukui H, Ishizaka S. Immunomodulatory effects of ursodeoxycholic acid on immune responses. Hepatology. 1992;16:358-364. [PubMed] |

| 23. | De Groote J, Fevery J, Lepoutre L. Long-term follow-up of chronic active hepatitis of moderate severity. Gut. 1978;19:510-513. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Czaja AJ. Features and consequences of untreated type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. Liver Int. 2009;29:816-823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Feld JJ, Dinh H, Arenovich T, Marcus VA, Wanless IR, Heathcote EJ. Autoimmune hepatitis: effect of symptoms and cirrhosis on natural history and outcome. Hepatology. 2005;42:53-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kogan J, Safadi R, Ashur Y, Shouval D, Ilan Y. Prognosis of symptomatic versus asymptomatic autoimmune hepatitis: a study of 68 patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:75-81. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Muratori P, Lalanne C, Barbato E, Fabbri A, Cassani F, Lenzi M, Muratori L. Features and Progression of Asymptomatic Autoimmune Hepatitis in Italy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:139-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Abe M, Mashiba T, Zeniya M, Yamamoto K, Onji M, Tsubouchi H. Present status of autoimmune hepatitis in Japan: a nationwide survey. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1136-1141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |