Published online Jun 28, 2016. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v8.i18.762

Peer-review started: December 10, 2015

First decision: January 18, 2016

Revised: March 17, 2016

Accepted: April 5, 2016

Article in press: April 6, 2016

Published online: June 28, 2016

Processing time: 197 Days and 20.6 Hours

AIM: To investigate Chinese physicians’ awareness of the 2010 guidelines on the treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection.

METHODS: This was a quantitative survey that investigated the characteristics and practices of physicians who were treating patients with hepatitis B, the profile of their patients and physician practices regarding the diagnosis and treatment of HBV at the time of the survey. Participants were randomly selected from available databases of Chinese physicians and requested to complete either an online or paper-based survey. Data from the survey responses were analysed. For data validation and interpretation, qualitative indepth interviews were conducted with 39 of the respondents.

RESULTS: Five-hundred completed surveys, from 663 physicians were available for analysis. A mean of 175 chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients was seen by each physician every month, of whom 85 (49%) were treated in line with therapeutic indications stated in the 2010 guidelines. A total of 444 (89%) physicians often (> 60% of the time) adhered to the guidelines. Most physicians used antiviral medications as recommended. For patients with compensated and decompensated cirrhosis, 342 (68%) and 336 (67%) of physicians, respectively, often followed the recommendation to use potent nucleos(t)ide analogues with a high genetic barrier to resistance, using the appropriate treatment more than 60% of the time. Physicians from infectious disease or liver disease departments were better informed than those from gastrointestinal or other departments.

CONCLUSION: The majority of Chinese physicians often adhere to Chinese 2010 CHB guidelines and are well-informed about the use of antiviral medications for hepatitis B.

Core tip: In general, the majority of Chinese physicians often adhere to Chinese 2010 chronic hepatitis B guidelines and they are well-informed about the use of antiviral medications for hepatitis B. Most of the physicians who participated in our survey used antiviral medications as recommended. For patients with compensated and decompensated cirrhosis, more than two-thirds of physicians, often followed the recommendation to use potent nucleos(t)ide analogues with a high genetic barrier to resistance. Our survey also showed that physicians from infectious disease or liver disease departments were better informed than those from gastrointestinal or other departments.

- Citation: Wei L, Jia JD, Weng XH, Dou XG, Jiang JJ, Tang H, Ning Q, Dai QQ, Li RQ, Liu J. Treating chronic hepatitis B virus: Chinese physicians’ awareness of the 2010 guidelines. World J Hepatol 2016; 8(18): 762-769

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v8/i18/762.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v8.i18.762

The clinical management of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) has undergone dramatic changes over the past two decades following the registration worldwide of several antiviral agents that effectively suppress hepatitis B virus (HBV) loads[1-4]. Currently, the primary aim of CHB treatment is the permanent suppression of HBV replication to decrease viral infectivity and pathogenicity[5]. Two different classes of drug are used to treat HBV: Conventional interferon (IFN) or pegylated IFN, and oral nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs). Nucleoside analogues include lamivudine, telbivudine, clevudine and entecavir, while nucleotide analogues include adefovir dipivoxil and tenofovir dipivoxil fumarate[5]. Guidelines have been developed to help standardise the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of CHB. Key clinical practice guidelines have been developed by the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL; 2012 update)[5], the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL; 2012 update)[6] and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD; 2009 update)[7]. In March 2015, the World Health Organization issued its first-ever guidance for the treatment of CHB[8].

Chinese CHB guidelines were first developed in 2005 by the Chinese Society of Hepatology, Chinese Medical Association and Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases[9], and updated in 2010[10]. The 2010 guidelines state that no antiviral treatment is recommended for chronic and inactive HBV carriers, although regular diagnostic tests should be performed to ensure criteria for antiviral therapy are not met. For hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)positive and HBeAgnegative patients with CHB, both IFNs and NAs are recommended as first-line treatments. However, due to these patients’ need for long-term treatment, it is recommended that those with HBeAgnegative CHB or CHB with cirrhosis (compensated or decompensated) receive treatment with NAs that have a high genetic barrier to resistance[10].

It is known that the implementation of treatment guidelines in clinical practice can improve the outcome of patients, but despite wide promulgation, many guidelines are not readily accepted by physicians or incorporated in clinical management strategies[11]. There is some evidence of poor adherence to HBV treatment guidelines among healthcare providers in the United States who treat HBV/human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) co-infected patients[12], but in general, real-world clinical practice with CHB guidelines is not well understood. In China, the prevalence of HBV is high[13,14] and physician adherence to CHB treatment guidelines could potentially have an important impact on the long-term outcome of a large proportion of the CHB population. To date, there are limited available data on how CHB is treated in real-world clinical practice in China and whether physicians adhere to available guidelines. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate Chinese physicians’ awareness of the updated 2010 Chinese CHB treatment guidelines[10], to improve understanding of guideline use in clinical practice, and to assist with the development of future CHB clinical practice guideline updates.

This was a quantitative survey to investigate the characteristics of physicians who treat patients with HBV, the profile of their patients and physician practices regarding the diagnosis and treatment of HBV. Three study dimensions were therefore included. The first captured physician gender, location, affiliation and professional position. The second captured number of CHB patients treated, proportion of HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients and the proportion of patients with cirrhosis. The third captured physician reference to the Chinese 2010 CHB guidelines[12], as well as specific data on physician prescription, treatment and follow-up practices.

Participants were randomly selected from internal databases of Chinese physicians, belonging to either SmithStreet (Shanghai, China) or Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS; Shanghai, China). SmithStreet has proven experience in healthcare survey development, a focus on China growth strategies, and relevant experience in consumer health and prescription medicines. For survey data capture, physicians working in Chinese grade III hospitals and in liver disease or infectious disease departments were targeted, with appropriate segmentation to obtain an even distribution of physicians by region, city tier and professional position. In China, the Ministry of Health grades hospitals according to a three-grade system, which assesses a hospital’s ability to provide medical care and medical education, and to conduct medical research. In general, grade III hospitals are considered the highest level in China. These hospitals are able to provide high quality, specialized care in well-equipped facilities. Considering the availability of medical education and specialized care at grade III hospitals, in general, physicians at these hospitals are thought to at the forefront of clinical medicine.

Participants were approached by SmithStreet via phone or email, and also face-to-face for qualitative follow-up questions. There was a target sample size of 500 respondents, which was deemed sufficient to allow nationwide representation of the data. Participants were required to be physicians currently treating patients with HBV, but there were no other pre-specified eligibility criteria or screening questions prior to enrolment.

Survey questions were developed by SmithStreet. Contributions were made by leading physicians, who reviewed and provided feedback on the questions prior to survey initiation. Data were collected remotely online, via the SurveyMonkey® platform (https://www.surveymonkey.com). Physicians who were unable to complete the survey online were provided an offline survey by SmithStreet, which was distributed by post or fax; offline surveys were subsequently returned by email to SmithStreet for data collection and analysis.

Instruction guides for online and offline surveys were provided to participating physicians. A pilot online survey was tested on five randomly selected representative physicians outside of the target pool to obtain feedback on language, content and interface structure. Participant responses were captured by the SurveyMonkey® platform. For consistency during data extraction and analysis, data from the offline surveys were entered into SurveyMonkey® by SmithStreet. Respondents who completed the survey offline were given the opportunity to review their responses.

All coding and data analyses were conducted by SmithStreet. Responses were reviewed to eliminate repeat submissions and incomplete responses. Follow-up phone calls were conducted with 25 randomly selected online respondents to verify their participation. Responses that were deemed invalid or defective were eliminated from the analyses. To assist with data validation and interpretation, qualitative in-depth interviews were conducted with 39 respondents of the quantitative survey. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Qing-Qing Dai of SmithStreet. No statistical tests were performed. The data are presented as percentages and described.

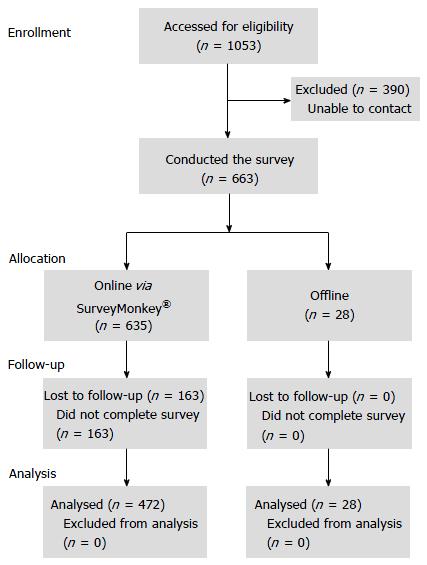

The first participant was screened on 21 March 2013 and the last participant completed the survey on 1 September 2013. Participant flow through the study is shown in Figure 1. Of 663 physicians who completed the survey, 500 were available for analysis (472 from online surveys); of these, 194 were recruited through BMS’ physician database and 306 were recruited via SmithStreet’s physician database. Demographics and background characteristics of the responding physicians are shown in Table 1. The majority were female, from South, North or East China, held attending level positions or above, and worked in an infectious diseases department (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Physician response (n = 500) |

| Female physicians, n (%) | 282 (56) |

| Location within China, n (%) | |

| North | 110 (22) |

| South | 116 (23) |

| East | 98 (20) |

| Central | 64 (13) |

| Northeast | 43 (9) |

| Northwest | 52 (10) |

| Southwest | 17 (3) |

| City tier, n (%) | |

| I | 110 (22) |

| II | 171 (34) |

| III | 143 (29) |

| IV | 46 (9) |

| V | 30 (6) |

| Hospital grade, n (%) | |

| I | 1 (0) |

| II | 79 (16) |

| III | 420 (84) |

| Hospital affiliation, n (%) | |

| Gastroenterology | 79 (16) |

| Infectious disease | 265 (53) |

| Liver disease | 139 (28) |

| Other | 17 (3) |

| Hospital position, n (%) | |

| Chief | 151 (30) |

| Associate chief | 90 (18) |

| Attending | 147 (29) |

| Resident | 112 (22) |

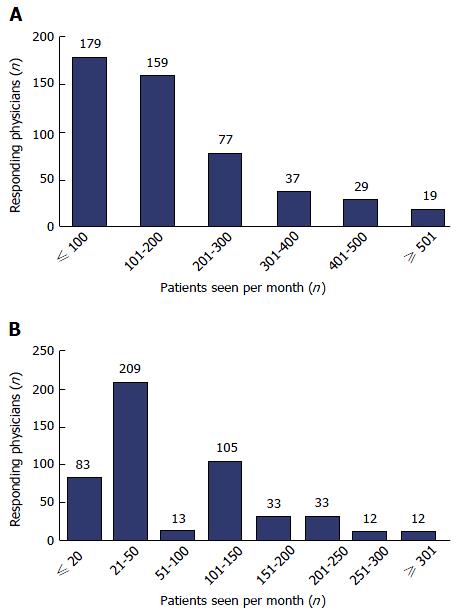

Segmentation of physicians by number of CHB patients seen per month is shown in Figure 2. A mean of 175 CHB patients was seen by each physician every month, of whom 85 (49%) were treated with antiviral therapy in line with the therapeutic indications as stated in the Chinese 2010 CHB guidelines[12] and 46 (26%) had cirrhosis (27 with compensated cirrhosis). Among treatment-naive CHB patients, 25 (14%) were HBeAgpositive and 21 (12%) were HBeAgnegative. The number of patients seen each month varied by physician rank, hospital grade, city tier and region; however, the number of treatmentnaïve HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients seen by physicians each month was similar across different regions and city tiers. (In China, cities are ranked into tiers (tier I through IV) according to size and economic development, with tier I cities generally the largest economical hubs).

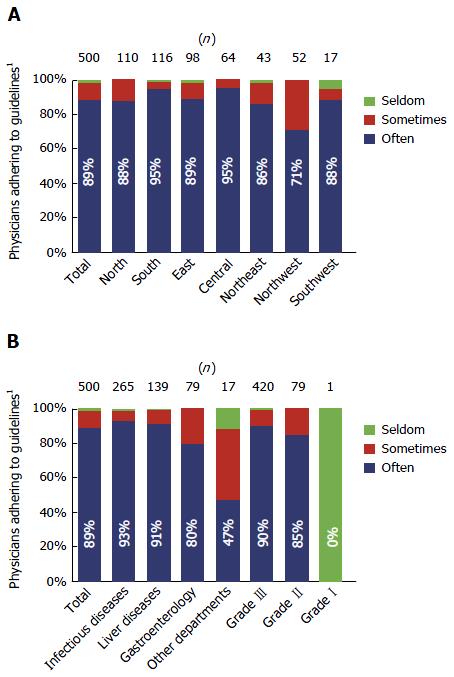

A total of 444 (89%) surveyed physicians indicated that they “often” (defined as more than 60% of the time) adhered to the Chinese 2010 CHB guidelines. In particular, more than 90% of physicians from infectious disease or liver disease departments often adhered to the guidelines (Figure 3).

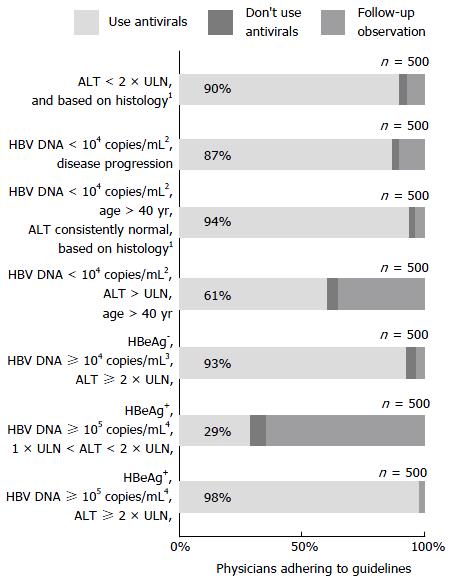

Most physicians used antiviral medications consistent with guideline recommendations. However, in patients older than 40 years, who were HBV DNA-positive (but with < 1 × 104 copies/mL), and with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels above the upper limit of normal (ULN), 196 (39%) of the surveyed physicians did not consider antiviral medication necessary (Figure 4). The guideline recommends that in these patients, the presence of liver fibrosis (as judged by the physician), should be an indication for antiviral therapy.

A total of 354 (71%) physicians could identify the distractor (HBeAgpositive, HBV DNA ≥ 105 copies/mL, 1 × ULN < ALT < 2 × ULN), including 194 (73%) of those from infectious disease departments, 106 (76%) from liver disease departments, 49 (62%) from gastroenterology departments, and five (29%) from other departments.

When asked for a response regarding the reasonable treatment course for antiviral medications, 422 (84%) physicians considered that more than 12 mo (responses for “12 to 18 mo” and “more than 18 mo”) of consolidation treatment was needed for HBeAg-positive patients following serological conversion. However, this proportion was lower among physicians from gastroenterology (n = 54; 68% of all physicians from gastroenterology departments) or other (n = 11; 65%) departments, than among physicians from infectious disease (n = 236; 89%) or liver disease (n = 121; 87%) departments. For HBeAg-negative patients following serological conversion, 302 (60%) physicians considered that more than 18 mo of consolidation treatment was needed. However, this proportion was lower among physicians from gastroenterology (n = 40; 51% of all physicians from gastroenterology departments) or other (n = 8; 47%) departments, than among physicians from infectious disease (n = 169; 64%) or liver disease (n = 85; 61%) departments.

For patients with compensated and decompensated cirrhosis, 342 (68%) and 336 (67%) physicians, respectively, followed guidelines recommending the use of potent NAs with a high genetic barrier to resistance, using the appropriate treatment more than 60% of the time. This recommendation was followed most frequently by physicians from liver disease departments for patients with compensated and decompensated cirrhosis (both n = 100; 72%). A low proportion of physicians did not follow this recommendation (use of the appropriate treatment less than 30% of the time) for compensated cirrhosis (n = 17; 3%) and decompensated cirrhosis patients (n = 20; 4%).

Our survey results show that the majority of Chinese physicians often adhered to Chinese 2010 CHB guidelines[10]. Physicians from liver disease and infectious disease departments were most familiar with the guidelines, but physicians from other departments adhered to the guidelines less frequently, indicating that access to, or awareness of CHB treatment guidelines in China could be improved.

The physicians in this survey saw a mean of 175 CHB patients every month. This was below the number expected, especially for physicians working in tier I cities and grade III hospitals (210 and 184 patients per month, respectively; data not shown). We found 26% of patients to have cirrhosis, 29% to be HBeAgpositive and 23% to be HBeAg-negative. Nearly half (49%) of patients were treated in line with guidelines for various indications, and nearly nine out of 10 (89%) responding physicians often adhered to the guidelines; based on our clinical experience, this number is higher than expected.

In China, most patients with HBV are treated in infectious disease or liver disease departments, with physicians working in these departments generally regarded as specialists. Accordingly, when our survey results were analysed by hospital department, we found that adherence was greatest among physicians from infectious disease or liver disease departments. Adherence was slightly lower among physicians working in gastroenterology departments, but much lower among physicians from other departments. In Northwest China, the percentage of physicians who adhered to the guideline was noticeably lower than in other regions. Although speculative, this may be due to a higher proportion of respondents who were residents, and a lower proportion of respondents who were chief physicians in Northwest China compared with other regions (data not shown). In addition, Northwest China had the second highest proportion of respondents from other departments (6%) and the second lowest combined proportion of respondents who were specialists (48% from infectious disease departments plus 23% from liver disease departments; data not shown).

Previous publications have demonstrated inadequacy of CHB management and need for improved education among Chinese physicians[15,16]. Even with the availability of CHB guidelines from key international associations, continual advancement in our understanding of CHB and availability of new data can create ongoing challenges regarding who should be treated and for how long[17]. Chao et al[16] (2010) previously reported that there is a lack of basic knowledge surrounding HBV natural history, prevention and transmission. They identified critical gaps in HBV knowledge; in particular, 34% of physicians surveyed in their study did not know that CHB is often asymptomatic, 29% did not know that CHB infection confers a high risk of cirrhosis, liver cancer and premature death, and only 31% knew the recommended protocol for testing liver function and screening for liver cancer in CHB[16].

In contrast, in our study, the majority of physicians were found to be well-informed about the importance of antiviral medication and were educated on the appropriate indications for their use. However, there was some inconsistency among physicians regarding the use of antiviral treatment for patients older than 40 years, who present with HBV DNA of < 1 × 104 copies/mL, and ALT levels above the ULN. The guideline recommends that these patients be initiated on antiviral therapy if they have liver fibrosis (as judged by the physician). For these patients, liver biopsy is clearly important when making treatment decisions.

As expected, and in line with the proportion of physicians who adhered to the Chinese 2010 CHB guidelines, physicians from infectious disease and liver disease departments were better able to identify the distractor, followed by those from gastroenterology departments and physicians from other departments.

According to the Chinese 2010 CHB guidelines, the endpoint for antiviral treatment in HBeAg-positive patients should be HBV DNA levels below the lower limit of detection, normalisation of ALT levels, HBeAg seroconversion, at least 1 year of consolidation therapy and a total treatment duration of at least 2 years. In HBeAg-negative patients, these criteria are the same for HBV DNA and ALT levels, but at least 1.5 years of consolidation therapy and a total treatment duration of at least 2.5 years is recommended[10]. We found that 84% and 60% of physicians often followed recommendations for consolidation therapy for HBeAg-positive and HBeAgnegative patients, respectively. Physicians from infectious disease or liver disease departments again showed greatest awareness of the guidelines in this context. For HBeAg-negative patients, the optimal duration of NA treatment is unknown unless hepatitis B surface antigen seroclearance has occurred, and the decision to stop therapy can be based upon clinical response and severity of the underlying liver disease[5]; this flexibility may explain the lower adherence to recommended endpoints for HBeAg-negative patients compared with HBeAg-positive patients.

As CHB requires long-term treatment, the Chinese 2010 CHB guidelines recommend that HBeAg-negative CHB patients and CHB patients with cirrhosis (compensated or decompensated) receive treatment with NAs that have a high genetic barrier to resistance[10]. We found that, in both patients with compensated and decompensated cirrhosis, over two-thirds of physicians often followed guidelines recommending the use of potent NAs with a high genetic barrier to resistance. While this finding is promising for the appropriate antiviral treatment of patients with CHB, this alignment with the guidelines was higher than expected.

Although the majority of Chinese physicians in our survey often adhered to Chinese 2010 CHB guidelines, our results also showed that there is a need to improve physicians’ awareness and knowledge of CHB guidelines. This was particularly evident among non-specialists, where a need for education on CHB and its treatment was confirmed. Although physicians from gastroenterology departments were relatively well-informed about CHB, their awareness of CHB guidelines was lower than that of specialist physicians from infectious disease or liver disease departments, implying that Chinese gastroenterologists may require additional training on HBV antiviral recommendations. The delay and reduction of liver cirrhosis is one goal of CHB treatment[5] and the Chinese 2010 CHB guidelines provide specific recommendations for antiviral treatment and follow-up in CHB patients with cirrhosis[10]. Since patients with cirrhosis are frequently referred to gastroenterologists, consensus statements for treatment of cirrhotic HBV patients with antiviral therapy should help educate Chinese gastroenterologists moving forward.

Other than general limitations associated with the acquisition of data using a survey design, the respondent pool in our survey could be considered a potential limitation leading to over- or underestimation of guideline awareness and uptake. In particular, our survey included only one grade I hospital, the majority of physicians came from grade III hospitals and physicians from Southwest China or other departments may have been under-represented. In addition, this survey was based upon the latest update to the Chinese CHB guidelines; because this update was published in 2010, and this survey was completed at the end of 2013, this survey may not reflect changes in physician attitudes or education in the past few years.

This survey has shown that the majority of Chinese physicians often adhered to Chinese 2010 CHB guidelines and were well-informed about the use of antiviral medication for HBV. However, there is a need to further educate non-specialist physicians who treat patients with CHB and to promote physician adherence to future CHB guidelines or updates.

The majority of Chinese physicians often adhere to Chinese 2010 CHB guidelines and they are well-informed about the use of antiviral medications for hepatitis B. In general, the physicians who participated in our survey used antiviral medications as recommended. For patients with compensated and decompensated cirrhosis, more than two-thirds of physicians, often followed the recommendation to use potent nucleos(t)ide analogues with a high genetic barrier to resistance. We found that physicians from infectious disease or liver disease departments were better informed than those from gastrointestinal or other departments.

The survey that formed the basis of this study was sponsored by Bristol-Myers Squibb. The survey was executed by SmithStreet. Editorial support for this manuscript was provided by Manette Williams, PhD, from Nucleus Global.

The implementation of treatment guidelines in clinical practice can improve the outcome of patients, but despite wide promulgation, many guidelines are not readily accepted by physicians or incorporated in clinical management strategies. In China, the prevalence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) is high and physician adherence to chronic hepatitis B (CHB) treatment guidelines could potentially have an important impact on the long-term outcome of a large proportion of the CHB population. There are limited available data on how CHB is treated in real-world clinical practice in China and whether physicians adhere to available guidelines. The authors investigated Chinese physicians’ awareness of the updated 2010 Chinese CHB treatment guidelines.

CHB patients require long-term treatment and it is recommended that those with hepatitis B e antigen negative CHB or CHB with cirrhosis (compensated or decompensated) receive treatment with nucleos(t)ide analogues that have a high genetic barrier to resistance. Despite these recommendations, many treatment naïve CHB patients do not receive appropriate treatment because physicians do not adhere to the treatment guidelines. The authors assessed how well Chinese physicians adhere to the Chinese CHB treatment guidelines, released in 2010.

The authors show that in China, the majority of Chinese physicians often adhere to Chinese 2010 chronic hepatitis B guidelines and they are well-informed about the use of antiviral medications for hepatitis B.

Despite high adherence rates, there was some inconsistency among physicians regarding the use of antiviral treatment for patients older than 40 years, who present with HBV DNA of < 1 × 104 copies/mL, and alanine aminotransferase levels above the upper limit of normal. The guideline recommends that these patients be initiated on antiviral therapy if they have liver fibrosis (as judged by the physician). For these patients, liver biopsy is clearly important when making treatment decisions.

HBV DNA levels, measure in copies/mL indicates the rate of viral replication. Low or undetectable levels (about 300 copies/mL) indicate “inactive infection”, whereas higher levels indicate “active infection”.

It is a well-designed study and provides useful information to physicians especially treating patients with hepatitis B about the trends in the treatment of CHB.

| 1. | Chen CJ, Yang HI, Su J, Jen CL, You SL, Lu SN, Huang GT, Iloeje UH. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA. 2006;295:65-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2309] [Cited by in RCA: 2396] [Article Influence: 119.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chen G, Lin W, Shen F, Iloeje UH, London WT, Evans AA. Chronic hepatitis B virus infection and mortality from non-liver causes: results from the Haimen City cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:132-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Iloeje UH, Yang HI, Su J, Jen CL, You SL, Chen CJ. Predicting cirrhosis risk based on the level of circulating hepatitis B viral load. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:678-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1164] [Cited by in RCA: 1182] [Article Influence: 59.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liang X, Bi S, Yang W, Wang L, Cui G, Cui F, Zhang Y, Liu J, Gong X, Chen Y. Epidemiological serosurvey of hepatitis B in China--declining HBV prevalence due to hepatitis B vaccination. Vaccine. 2009;27:6550-6557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 633] [Cited by in RCA: 719] [Article Influence: 42.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Liaw YF, Kao JH, Piratvisuth T, Chan HL, Chien RN, Liu CJ, Gane E, Locarnini S, Lim SG, Han KH. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2012 update. Hepatol Int. 2012;6:531-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 742] [Cited by in RCA: 797] [Article Influence: 56.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2323] [Cited by in RCA: 2411] [Article Influence: 172.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2125] [Cited by in RCA: 2176] [Article Influence: 128.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 8. | World Health Organization. Guidelines for the prevention, care and treatment of persons with chronic hepatitis B infection, 2015. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Chinese Society of Hepatology and Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases, Chinese Medical Association. Guideline on prevention and treatment of chronic hepatitis B in China (2005). Chin Med J (Engl). 2007;120:2159-2173. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Chinese Society of Hepatology and Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases, Chinese Medical Association. [The guideline of prevention and treatment for chronic hepatitis B (2010 version)]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2011;19:13-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA, Rubin HR. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282:1458-1465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4499] [Cited by in RCA: 4681] [Article Influence: 173.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jain MK, Opio CK, Osuagwu CC, Pillai R, Keiser P, Lee WM. Do HIV care providers appropriately manage hepatitis B in coinfected patients treated with antiretroviral therapy? Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:996-1000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lu FM, Li T, Liu S, Zhuang H. Epidemiology and prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in China. J Viral Hepat. 2010;17 Suppl 1:4-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lesmana LA. Hepatitis B: overview of the burden of disease in the Asia-Pacific region. Liver Int. 2006;26:3-10. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ning LH, Hao J, Liao ZL, Zhou YY, Guo H, Zhao XY. A survey on the current trends in the management of hepatitis B in China. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:884-889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chao J, Chang ET, So SK. Hepatitis B and liver cancer knowledge and practices among healthcare and public health professionals in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ahn SH, Chan HL, Chen PJ, Cheng J, Goenka MK, Hou J, Lim SG, Omata M, Piratvisuth T, Xie Q. Chronic hepatitis B: whom to treat and for how long? Propositions, challenges, and future directions. Hepatol Int. 2010;4:386-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Akbar SMF, Coban M, He JY, Toyoda T S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D