Published online Mar 27, 2015. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i3.633

Peer-review started: May 8, 2014

First decision: June 27, 2014

Revised: December 29, 2014

Accepted: January 9, 2015

Article in press: January 9, 2015

Published online: March 27, 2015

Processing time: 327 Days and 16.6 Hours

The infection caused by the tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus leads to the development of hydatic disease. It is the most frequent mediterranean parasitic infection that commonly affects the liver and rarely involves multiple organs. Herein, we report an exceptional and confusing presentation of hepatopulmonary and splenic hydatidosis due to Echinococcus granulosus that caused diagnostic problems occuring in a 70-year-old man, treated with chemotherapy, with favorable outcome. This was a very unusual case of disseminated hydatid cyst highlighting the interest of keeping a high level of clinical suspicion of this diagnosis every time we have a cystic lesion of the liver.

Core tip: The infection caused by the tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus (E. granulosus) leads to the development of hydatic disease. It is the most frequent mediterranean parasitic infection that commonly affects the liver and rarely involves multiple organs. The diagnosis is usually based on ultrasonography and serological markers. This paper reports an exceptional and confusing presentation of hepatopulmonary and splenic hydatidosis due to E. granulosus that caused diagnostic problems treated with chemotherapy, with favorable outcome.

- Citation: Hammami A, Hellara O, Mnari W, Loussaief C, Bedioui F, Safer L, Golli M, Chakroun M, Saffar H. Unusual presentation of severely disseminated and rapidly progressive hydatic cyst: Malignant hydatidosis. World J Hepatol 2015; 7(3): 633-637

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v7/i3/633.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v7.i3.633

Hydatidosis due to Echinococcus granulosus (E. granulosus) is an endemic parasitic zoonosis characterized by worldwide distribution particularly in Mediterranean countries. It remains a major public health problem in developing countries. The disease commonly affects the liver (> 65%), and less frequently the lungs (> 25%)[1]. Disseminated hydatidosis is an infrequent condition that usually results from the rupture of a liver cyst, with subsequent seeding of protoscolices in the abdominal cavity[2]. Hydatid disease may be asymptomatic or present with complications. Sometimes unusual locations as well as cyst metastasis can produce a diagnostic dilemma and make differential diagnosis from other abdominal cystic lesions sometimes difficult. The particularity of this case is related to its unusual clinical presentation. The purpose of this paper is to emphasize the fact that hydatid disease can involve any organ of the body and can have an unusual presentation; therefore, a high index of suspicion and correct diagnosis is justified in order to prevent complications and chances of recurrence.

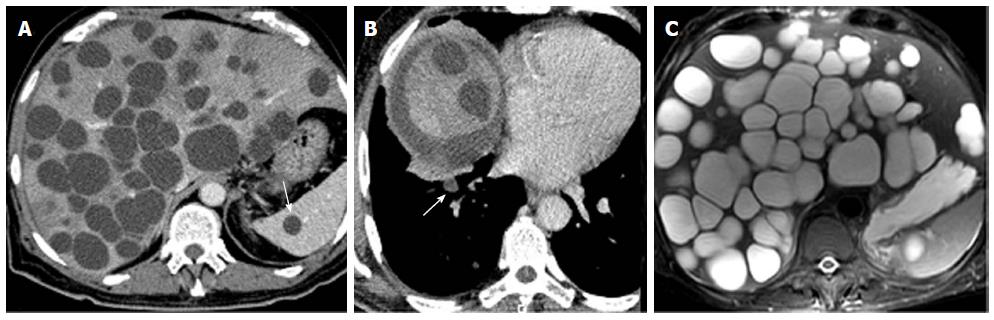

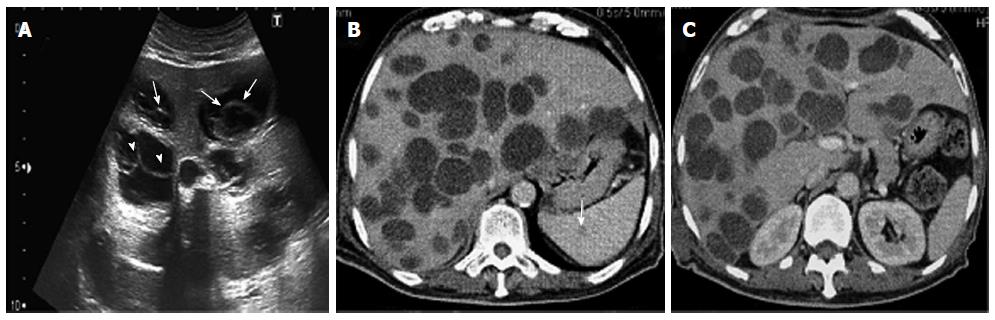

A 70-year-old man had had intermittent abdominal pain in the right hypochondrium, for 2 wk, with no radiation, associated to fever that appeared one day before the admission. He had a medical history of diabetes and hypertension and was followed for benign prostatic hyperplasia. He had, in the past year, an abdominal ultrasound which was absolutely normal except for the prostatic hypertrophy. He was engineer in agriculture and he had been in Australia, for 6 mo, 30 years ago. There was no history of vomiting, weight loss, change in bowel habit, or urinary symptoms. Clinical examination revealed apyrexia, absence of icterus, normal blood pressure and heart rate, mild tenderness in the right hypochondrium with hepatomegaly, and a scar of a recent injury in the ankle. Hematological tests showed a slight anemia and a mild leukocytosis (10800/mm3). Renal function and serum electrolytes tests were within normal limits. Liver function tests initially revealed anicteric cholestasis [alkaline phosphatase (ALP): 1.2N, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT): 19N] without cytolysis. The hepatic function was normal (Factor V: 100%). The C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated to 85 mg/L. The abdominal computed tomography scan showed multiple thin wall cystic mass with homogeneous fluid density contains in the liver (Figure 1A). There was non wall enhancement. Basal chest sections revealed smaller cystic lesion in the lung (Figure 1B). Abdominal MRI confirmed the simple cystic nature of the hepatic lesions (Figure 1C). The liver cysts was then suspected as infectious or tumor. His tumor markers were normal. A serum Western blot and Elisa tests for hydatidosis (Echinococcus granulosus) were negative twice. Laboratory studies indicated negative amoebic antibodies. A guided puncture of cysts content was performed under scenographic control. The fluid aspirated from the hepatic cyst was limpid. The smears demonstrated the absence of protoscolices. Pathologic reports were negative for malignant cells. Bacteriological examination showed a gram positive Cocci. Then, the diagnosis of hepatic abscess secondary to staphylococcus septicemia from cutaneous wound in diabetic patient was retained. Thus, our patient was treated with antibiotics during 3 wk. The course of his disease was marked by the occurrence of fever, icterus and extensive edema. Upon examination, we noticed the increase of the hepatomegaly. Biological tests revealed icteric cholestasis [conjugated bilirubin (CB): 19 N, GGT: 30N]. CT scan control showed no improvement of hepatic lesions despite an appropriate treatment; otherwise, we noted a dissemination of pulmonary lesions and occurrence of spleen cysts. The volume of the liver was enlarged, causing compression of the inferior vena cava without thrombosis, leading to the diffuse edema. Therefore, we suspected a malignancy with hepatic and pulmonary metastasis despite the absence of typical radiological signs. Upper and lower endoscopy showed no tumor. The bone scintigraphy was normal. At this stage, considering the absence of formal radiological and biological features of hydatid cyst and the lack of solid arguments for tumor, we decided to enlarge the spectrum of antibiotics associated to anticoagulant treatment and lymphatic drainage, with close monitoring. The patient was followed by routine biochemistry, CRP, procalcitonin measurement with abdomino-pelvic ultrasonography. Another hydatic serology was performed, after 6 wk, as we have no idea about the origin of these lesions. This time, the serology was positive for E.granulosus with total serum antibodies by hemagglutination assay at the level of 2560 (n < 10), and Immunoglobulin G (IgG) by ELISA test at the level of 58 kU/L (n <10). Serology tests for Echinococcus multilocularis were negative. Then, the diagnosis of CE was confirmed, and chemotherapy was decided. Our patient was treated with oral albendazole (400 mg twice daily) in association with praziquentel 50 mg/kg per day during 15 d. This treatment was well tolerated and led to clinical and biological improvement with especially the decrease of cholestasis (GGT: 9N, CB: normal). After 3 wk of anti-parasitic chemotherapy, transabdominal ultrasound showed a significant reduction in the number and the size of hepatic cysts with appearance of detached membrane and daughter vesicles within some cysts (Figure 2A). These findings are typical of hydatid disease. On the 2 mo CT scan control; there was a significant regression of the hepatomegaly and the cystic liver involvement (Figure 2, Panel B). Currently, the condition of our patient is very well. He will be maintained on Albendazole with regular follow-up. He was discharged from the hospital after 4 mo.

Hydatid disease (HD) is a parasitic infection caused by Echinococcus granulosus[1] that represents a major public health problem in the Mediterranean region[3]. Humans are not included in the parasitic life cycle of Echinococcus granulosus. They can be intermediate hosts who become infected by accidental ingestion of food contaminated with eggs of E. granulosus shed by definitive hosts[4].

The liver is the major organ of echinococcal cysts (CE) involvement (60%-70% of cases) followed by the lungs (10%-25%), and less frequently, other organs such as brain[5], bones[6], and heart[7]. HD is usually asymptomatic and diagnosed incidentally, because cyst growth rate is commonly slow and progressive, ranging from 1 to 5 mm in diameter per year. Most primary infected patients have single cyst, but up to 20%-40% of them can develop multiple cysts[8]. Symptoms depend on organs affected, cyst size and number, the mass effect within adjacent organs and structures. The most frequent symptoms include asthenia and abdominal pain. Patients may also present jaundice, hepatomegaly or anaphylaxis due to cyst leakage or rupture. Simultaneous development of pulmonary and hepatic hydatid cysts is an unusual manifestation of hydatid disease that could be observed in less than 10% of cases[9]. It represents a specific entity called hepatopulmonary hydatidosis (HPH). The most common symptoms identified in patients with HPH are from the respiratory system, including cough, chest pain, dyspnea and hemoptysis[10]. Secondary splenic hydatid disease usually occurs after systemic dissemination or intraperitoneal spread complicating ruptured hepatic hydatid cyst.

Herein, we report an exceptional and confusing presentation of hepatopulmonary and splenic hydatidosis due to E. granulosus that caused diagnostic problems. The review of the literature revealed that it was the first case characterized by a fulminant dissemination of hydatid cysts through organs.

Appropriate clinical diagnosis of CE is necessary for early and adequate management of hepatic echinococcosis. It is generally approved that the combined use of ultrasonography and immunodiagnosis facilitate the distinction of echinococcal cysts from other hepatic cystic lesions[1]. The differential diagnosis of hepatic hydatid cyst includes abscess, hemangioma, and non-parasitic cysts such as solitary bile duct cyst, polycystic disease, hepatobiliary cystadenoma. Unilocular hydatid cysts appear on ultrasound as anechoic unilocular fluid-filled space with imperceptible walls and posterior acoustic enhancement. Ultrasonography is not always able to differentiate hydatid cysts from other hepatic lesions, like tumors or liver abscesses, which reflect the lack of pathognomonic radiological signs. On ultrasound, a bile duct cyst appears as a well-circumscribed anechoic lesion with increased through-transmission of sound and no evidence of mural nodularity. There are no specific radiological features for hemangioma. They are typically well defined hyperechoic lesions. However, a small proportion are hypoechoic. They may or may not show peripheral feeding vessels. In autosomal polycystic liver disease, the numerous hepatic cysts of various sizes have identical features to those described for benign developmental hepatic cyst. On CT scan and MRI, the simple hydatid cyst is defined as a well-demarcated water attenuation lesion that does not enhance after the administration of intravenous contrast[11,12]. Ultrasound may detect detached endocyst membranes and daughter cysts (vesicles within the mother cyst), which are highly specific for hydatid disease. Detachment of the membranes inside the cyst is referred to as “the water lily” sign. Among serologic tests, immunoelectrophoresis has been reported to be the most specific for the primary diagnosis and postsurgical follow-up[13], and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) represents a valuable diagnostic test for the initial screening[1]. In the present case, the first Serological tests were negative for specific IgG antibodies to E. granulosus by ELISA. The negative serology made the diagnosis of hydatid cysts more complicated. This test is limited by the high percentage of false-negative results and the large variability in its sensitivity and specificity between laboratories. Serologic tests do not supplant clinical or imaging investigations but they can, however, confirm the hydatid origin of a cyst. In doubtful cases, for example undetectable anti-Echinococcus antibodies or in patients whose hepatic cysts cannot be differentiated from liver abscess or neoplasms, ultrasonography-guided fine needle puncture may represent an additional diagnostic option. The demonstration of protoscolices or hydatid membranes or echinococcal antigens/DNA in the aspirated cyst fluid can confirm, in fact, the diagnosis of CE. In the current case, the content of the aspirated fluid showed no protoscolices with made the diagnosis more complicated. Anthelmintic coverage is important to reduce the risk of dissemination of CE: albendazole should be prescribed for 4 d before the procedure and continued for at least 1 mo after having punctured an E. granulosus cyst[14,15]. In the current case, the puncture of the cyst fluid, done without anthelmentic prophylaxis, did not show any protoscolices which made the diagnosis more difficult.

The main goal the treatment of hepatic hydatid disease should be the complete elimination of the parasite and prevention of recurrence of the disease with minimum morbidity and mortality risks. Three therapeutic modalities are validated in the treatment of hepatic CE: medical treatment, surgery (with open or laparoscopic approach) and percutaneous treatments (PTs)[16]. For many years, surgery was the first therapeutic option for hydatid disease[1]. Puncture, aspiration, injection, re-aspiration (PAIR) is a relatively recent and minimally invasive therapeutic option, introduced in the two past decades, and developed as an interesting alternative to surgery. It is a percutaneous treatment that consists of puncture of the cyst, aspiration of cyst fluid, injection of hypertonic saline and absolute alcohol that had a scolicidal effect, and re-aspiration of the cyst contents (PAIR) under sonographic guidance[17]. This treatment is considered in case of single or multiple cysts, which cannot be operated[1]. PAIR represents an effective and safe procedure[18] with low rates of complications[1] and is the unique method that provides direct diagnosis concerning the parasitic nature of the cysts in doubtful cases[18]. Chemotherapy based on benzimidazole carbamate compounds (albendazole and mebendazole) have, for a long time, remained the cornerstone of medical therapy for echinococcosis[1]. It has very effective results in patients with multiple or inoperable cysts and those with peritoneal hydatid cysts[19]. Albendazole, an oral benzimidazole antihelmintic agent, is a drug of choice for the medical therapy of echinococcal disease[20]. The dose of drug is 10 to 15 mg/kg per day in 2 divided doses given in cycles of 4 wk, without drug therapy for 2 wk. This regimen should be maintained for several cycles depending on the severity of disease or the improvement of patients[20,21]. Praziquantel, an isoquinoline anthelmintic, is a potent protoscolicidal agent in vitro[19,20]. The usage of albendazole with praziquantel together may be more effective than albendazole alone.

In conclusion, despite the progress made in imaging techniques and therapeutic modalities, the diagnosis of hydatid disease remains a problematic issue. The diagnosis of non complicated hepatic hydatidosis is based on clinical suspicion, combined to suggestive factors such as the patient’s origin and occupation in order to identify high-risk patients. Many unresolved problems are still waiting for a solution; for instance, there is a need for prevention programs able to monitor and control parasite spreading. The present report describes clinical findings of very unusual and rapidly progressive case of malignant CE which caused a diagnosis dilemma.

Symptoms were common to other hepatic diseases, diagnsotic delay, rapidly extensive hydatidosis.

Mild tenderness in the right hypochondrium with hepatomegaly.

Abscess, hemangioma, solitary bile duct cyst, polycystic disease, and hepatobiliary cystadenoma are the main differential diagnosis. Ultrasonography and CT scan aspects help to distinguish them.

Immunoelectrophoresis has been reported to be the most specific for the primary diagnosis. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay represents a valuable diagnostic test for the initial screening.

Ultrasound may detect detached endocyst membranes and daughter cysts (vesicles within the mother cyst), which are highly specific for hydatid disease.

Three therapeutic modalities: chemotherapy (benzimidazole carbamate compounds), surgery and percutaneous treatments.

This is the first case of very rapidly disseminated hydatid cyst with atypical presentation that caused diagnostic problems. It justifies that a high level of vigilance towards parasitic infections of the liver should be maintained especially in endemic countries.

Hydatid disease is still a major public health problem in endemic regions. This diagnosis should be suspected in case of cystic lesions of the liver. Accurate diagnosis of this disease represents a challenge. It allows a prompt management of the disease and prevention of the recurrence.

Good.

| 1. | Moro P, Schantz PM. Echinococcosis: a review. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:125-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 573] [Cited by in RCA: 712] [Article Influence: 41.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Majbar MA, Souadka A, Sabbah F, Raiss M, Hrora A, Ahallat M. Peritoneal echinococcosis: anatomoclinical features and surgical treatment. World J Surg. 2012;36:1030-1035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Sheng Y, Gerber DA. Complications and management of an echinococcal cyst of the liver. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:1222-1223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bükte Y, Kemaloglu S, Nazaroglu H, Ozkan U, Ceviz A, Simsek M. Cerebral hydatid disease: CT and MR imaging findings. Swiss Med Wkly. 2004;134:459-467. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Kalkan E, Torun F, Erdi F, Baysefer A. Primary lumbar vertebral hydatid cyst. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15:472-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Thameur H, Abdelmoula S, Chenik S, Bey M, Ziadi M, Mestiri T, Mechmeche R, Chaouch H. Cardiopericardial hydatid cysts. World J Surg. 2001;25:58-67. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Nunnari G, Pinzone MR, Gruttadauria S, Celesia BM, Madeddu G, Malaguarnera G, Pavone P, Cappellani A, Cacopardo B. Hepatic echinococcosis: clinical and therapeutic aspects. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1448-1458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | Doğan R, Yüksel M, Cetin G, Süzer K, Alp M, Kaya S, Unlü M, Moldibi B. Surgical treatment of hydatid cysts of the lung: report on 1055 patients. Thorax. 1989;44:192-199. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Aribas OK, Kanat F, Turk E, Kalayci MU. Comparison between pulmonary and hepatopulmonary hydatidosis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;21:489-496. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Hai S, Hirohashi K, Uenishi T, Yamamoto T, Shuto T, Tanaka H, Kubo S, Tanaka S, Kinoshita H. Surgical management of cystic hepatic neoplasms. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:759-764. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Carson JG, Huerta S, Butler JA. Hepatobiliary cystadenoma: a case report and a review of the literature. Curr Surg. 2006;63:285-289. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Zhang W, McManus DP. Recent advances in the immunology and diagnosis of echinococcosis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2006;47:24-41. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Khuroo MS, Dar MY, Yattoo GN, Zargar SA, Javaid G, Khan BA, Boda MI. Percutaneous drainage versus albendazole therapy in hepatic hydatidosis: a prospective, randomized study. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1452-1459. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Hira PR, Shweiki H, Lindberg LG, Shaheen Y, Francis I, Leven H, Behbehani K. Diagnosis of cystic hydatid disease: role of aspiration cytology. Lancet. 1988;2:655-657. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Brunetti E, Kern P, Vuitton DA. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Trop. 2010;114:1-16. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Junghanss T, da Silva AM, Horton J, Chiodini PL, Brunetti E. Clinical management of cystic echinococcosis: state of the art, problems, and perspectives. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:301-311. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Siracusano A, Teggi A, Ortona E. Human cystic echinococcosis: old problems and new perspectives. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2009;2009:474368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kaya Z, Gursel T. A pediatric case of disseminated cystic echinococcosis successfully treated with mebendazole. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2004;57:7-9. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Franchi C, Di Vico B, Teggi A. Long-term evaluation of patients with hydatidosis treated with benzimidazole carbamates. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:304-309. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Ayles HM, Corbett EL, Taylor I, Cowie AG, Bligh J, Walmsley K, Bryceson AD. A combined medical and surgical approach to hydatid disease: 12 years’ experience at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases, London. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2002;84:100-105. [PubMed] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Alimehmeti R, Dziri C, Turgut A S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL