Published online Jun 18, 2015. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i11.1586

Peer-review started: February 9, 2015

First decision: March 20, 2015

Revised: March 31, 2015

Accepted: April 16, 2015

Article in press: April 20, 2015

Published online: June 18, 2015

Processing time: 128 Days and 4.3 Hours

AIM: To investigate the potential burden of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and advanced fibrosis in a hispanic community.

METHODS: Four hundred and forty two participants with available ultrasonography data from the Cameron County Hispanic Cohort were included in this study. Each participant completed a comprehensive questionnaire regarding basic demographic information, medical history, medication use, and social and family history including alcohol use. Values of the nonalcoholic fatty liver disease fibrosis score (NFS), FIB4 index, BARD score, and Aspartate aminotransferase to Platelet Ratio Index (APRI) were computed using the blood samples collected within 6 mo of liver ultrasonography from each participant. Hepatic steatosis was determined by ultrasonography. As part of univariable analysis, for continuous variables, comparisons among groups were performed with student-t test, one way analysis of variance, and Mann-Whitney test. Pearson χ2 and the Fisher exact test are used to assess differences in categorical variables. For multivariable analyses, logistic regression analyses were performed to identify characteristics associated with hepatic steatosis. All reported P values are based two-sided tests, and a P value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS: The mean age and body mass index (BMI) of the study participants were 49.1 years and 31.3 kg/m2, respectively. Among them, 65.6% were females, 52% had hepatic steatosis, 49.5% had metabolic syndrome, and 29% had elevated aminotransferases. Based on established cut-offs for diagnostic panels, between 17%-63% of the entire cohort was predicted to have NASH with indeterminate or advanced fibrosis. Participants with hepatic steatosis had significantly higher BMI (32.9 ± 5.6 kg/m2vs 29.6 ± 6.1 kg/m2, P < 0.001) and higher prevalence rates of elevation of ALT (42.2% vs 14.6%, P < 0.001), elevation of aspartate aminotransferase (38.7% vs 18.9%, P < 0.001), and metabolic syndrome (64.8% vs 33%, P < 0.001) than those without hepatic steatosis. The NFS scores (P = 0.002) and the APRI scores (P = 0.002) were significantly higher in those with steatosis but the scores of the FIB4 index and BARD were similar between the two groups. After adjusting for age, gender and BMI, elevated transaminases, metabolic syndrome and its components, intermediate NFS and APRI scores were associated hepatic steatosis in multivariable analysis.

CONCLUSION: The burden of NASH and advanced fibrosis in the Hispanic community in South Texas may be more substantial than predicted from referral clinic studies.

Core tip: Among different racial and ethnic populations in the United States, Hispanics (predominantly of Mexican origin) are at particular risk for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and appear to have a more aggressive disease course. From the risk stratification and early intervention perspective, it is pivotal to define the magnitude of the burden of NAFLD in asymptomatic individuals in Hispanic communities and identify the subset with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Such community based data are scarce. In this study, we assessed the potential burden of NASH and advanced fibrosis in a Hispanic community utilizing four common diagnostic panels and ultrasonography.

- Citation: Pan JJ, Fisher-Hoch SP, Chen C, Feldstein AE, McCormick JB, Rahbar MH, Beretta L, Fallon MB. Burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and advanced fibrosis in a Texas Hispanic community cohort. World J Hepatol 2015; 7(11): 1586-1594

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v7/i11/1586.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v7.i11.1586

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) represents a spectrum of liver injury ranging from simple steatosis with a more benign course to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) which may progress to advanced fibrosis, cirrhosis and liver cancer[1,2]. Among different racial and ethnic populations in the United States, Hispanics (predominantly of Mexican origin) are at particular risk for NAFLD and appear to have a more aggressive disease course[3]. Hispanics accounted for nearly 50% of the United States population growth from 2000 to 2010 and are projected to reach 30% of the United States population within the next three decades[4]. Given the increasing prevalence and the expected growth in the Hispanic population, NAFLD poses a significant threat to this population.

From the risk stratification and early intervention perspective, it is pivotal to define the magnitude of the burden of NAFLD in asymptomatic individuals in Hispanic communities and identify the subset with NASH. Such community based data are scarce. Liver biopsy remains the standard for the diagnosis and staging of NASH, although invasiveness and cost preclude its use as a screening tool in general populations[5]. Markers that either individually or as composite panels predict the presence of NASH and advanced fibrosis of liver have been developed[6]. These panels have been advocated as a means to target liver biopsy to those at increased risk by identifying those at low, intermediate or high risk of NASH and advanced fibrosis. Practice guidelines recommend the NAFLD fibrosis score (NFS) as a clinically useful tool for identifying patients at higher likelihood of having bridging fibrosis and/or NASH[7]. Moreover, three panels derived from common anthropometric, hematological and biochemical parameters, the FIB4 index, the BARD score, and Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to Platelet Ratio Index (APRI) are used to predict advanced fibrosis in NAFLD[8-10]. These biomarkers and panels have been validated in cross-sectional studies of non-Hispanic cohorts evaluated for liver abnormalities but have not been evaluated in a population setting in Hispanics.

In this study, we assessed four diagnostic panels for NASH and fibrosis in relation to demographic, laboratory and liver ultrasonography data in asymptomatic individuals enrolled in the Cameron County Hispanic Cohort (CCHC); an extensively studied ethnic population-based cohort of community-dwelling Mexican Americans followed longitudinally who live in a city on the Texas-Mexico border.

This study has been approved by the institutional review board of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. Written consent was obtained from each participant. The CCHC (n = 3200) was originally established in 2003 and the participants were randomly selected based on the 2000 Census tract data in the city of Brownsville, Texas. Over 90% of them are Mexican Americans[11]. During initial visit, the participants completed a comprehensive questionnaire regarding basic demographic information, medical history, medication use, and social and family history including alcohol use. Starting in 2012, consenting participants were offered liver ultrasonography performed prospectively for the assessment of hepatic steatosis. The scores of the diagnostic panel for each participant were retrospectively computed using the blood samples collected within 6 mo of liver ultrasonography. Blood samples were taken and plasma aliquots immediately stored at -70 °C for a range of assays. Plasma glucose and complete blood count were performed on site. Stored specimens were sent in batches to a clinical laboratory for biochemistries, including hepatic function tests. Hepatitis C antibody was measured using the ORTHO® hepatitis C virus Version 3.0 Elisa Test System (Ortho Clinical Diagnostics Inc, Rochester, NY).

Ultrasonography was performed using an established protocol[12]. Study participants were asked to be fasting for at least 6 h prior to ultrasound examination to maximize the distention of gall bladder and to reduce food residue and gas in the upper gastrointestinal tract which may reduce image quality or preclude liver imaging. Trained technicians performed the abdominal ultrasonography with a 5 MHz transducer (Ch5-2, Siemens, Mountain View, CA, United States). During the scan, liver parenchyma was examined sub- and intercostally in the decubitus position as well in modified slightly oblique positions with the right arm above the head and the right leg stretched during all respiration cycles to identify the best approach and to avoid artefacts caused by the thorax. For diagnosis of hepatic steatosis, the following features were recorded: (1) Ultrasonographic contrast between the liver and right renal parenchyma of right intercostal sonogram in midaxillary line; (2) Brightness of the liver; (3) Deep attenuation of echo penetration into the deep portion of the liver and impaired visualization of the diaphragm; and (4) Impaired visualization of the borders of intrahepatic vessels and narrowing the their lumen. The overall gain, initial gain, and time gain compensation settings were kept within a narrow range. The ultrasonographic images were interpreted by one person (JJP) in a blinded fashion.

The presence of hepatic steatosis is qualitatively defined as a brighter liver parenchyma than the right kidney on ultrasonography. Based on the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHAHES III 1988-1994) definition, abnormal aminotransferases are defined as alanine aminotransferase (ALT) greater than 40 U/L for men and greater than 31 U/L for women; AST greater than 37 U/L for men and greater than 31 U/L for women. According to the United States National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III, the metabolic syndrome (MetS) is defined as the presence of at least 3 of the following 5 components: elevated waist circumference (> 102 cm for men and > 88 cm for women), elevated triglycerides (≥ 150 mg/dL), reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) (< 40 mg/dL for men and < 50 mg/dL for women), elevated blood pressure (≥ 130/85 mm Hg or use of medication for hypertension), and elevated fasting glucose (≥ 110 mg/dL)[13]. The formulae and cut-off scores of the diagnostic panels for detection of liver fibrosis are shown in the Table 1.

| Diagnostic panel | Formula | Cut-off scores for advanced fibrosis | |

| Absent | Present | ||

| BARD score[8] | Scale 0-4 | ≥ 2 | |

| BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2 = 1 point | |||

| AST/ALT ratio ≥ 0.8 = 2 points | |||

| DM = 1 point | |||

| FIB4 index[9] | Age (yr) × AST (U/L)]/(platelet (109) × [ALT (U/L)]1/2 | < 1.3 | > 2.67 |

| APRI[10] | (AST/ULN)/platelets (109/L) × 100 | ≤ 0.5 | > 1.5 |

| NAFLD fibrosis score[15] | -1.675 + 0.037 × age (yr) + 0.094 × BMI | < -1.455 | > 0.676 |

| (kg/m2) + 1.13 × IFG/DM (yes = 1, no = 0) | |||

| + 0.99 × AST/ALT ratio - 0.013 × platelet | |||

| (× 109/L) - 0.66 × albumin (g/dL) | |||

Descriptive data are presented as either means ± SD or median (interquartile range) for continuous variables, depending on whether the distribution of the variables is symmetrical or skewed. Frequencies and percentages are reported for categorical variables. As part of univariable analysis, for continuous variables, comparisons among groups were performed with student-t test, one way analysis of variance, and Mann-Whitney test. Pearson χ2 and the Fisher exact test are used to assess differences in categorical variables. For multivariable analyses, we used logistic regression. All reported P values are based two-sided tests, and a P value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). A statistical review of the study was performed by a biomedical statistician (Dr. Mohammad H Rahbar).

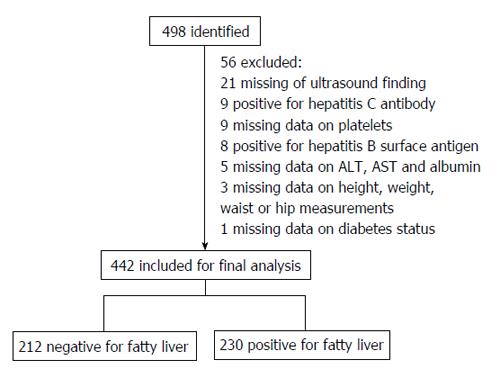

Four hundred and forty two participants were included in this study. Figure 1 shows an overview of the inclusion of individuals. Among the 498 consecutive participants recruited to this study, 56 were excluded for the following reasons: lack of data on liver ultrasonography (n = 21), positive Hepatitis C antibody (n = 9), lack of data on platelet counts (n = 9), positive Hepatitis B surface antigen (n = 8), lack of data on ALT, AST or albumin levels (n = 5), lack of data on height, weight, waist or hip measurements (n = 3), and lack of data on diabetes status (n = 1). Among the 442 remaining participants in this study, none reported excessive alcohol use (< 20 g of alcohol/day). As shown in Table 2, the mean age and body mass index (BMI) of the study participants was 49.1 years and 31.3 kg/m2, respectively. Among the participants in this study, 65.6% were females, 52% had hepatic steatosis, and nearly half had MetS. Approximately one-third of the participants had elevated ALT and AST. Ten participants had serum albumin less than 3.5 g/dL and 11 had platelet counts less than 150 × 109/μL. None of the participants with either hypoalbuminemia or thrombocytopenia had ascites on ultrasound. Regarding the individual components of the MetS, 37.8% had hypertension, 30.3% had hyperglycemia, 39.6% had hypertriglyceridemia, 73.3% had central obesity, and 60.4% had low HDL-C.

| Characteristics | |

| Age (yr) | 49.1 ± 14.2 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 290 (65.6) |

| Male | 152 (34.4) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.3 ± 6.1 |

| Hepatic steatosis | 230 (52.0) |

| Elevated ALT1 | 128 (29.0) |

| Elevated AST2 | 129 (29.2) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.0 (3.8-4.2) |

| Platelet (109/μL) | 243.5 (207.0-282.0) |

| DM3 | 97 (21.9) |

| Hypertension | 167 (37.8) |

| Hyperglycemia | 134 (30.3) |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 175 (39.6) |

| Low HDL-C | 267 (60.4) |

| Central obesity | 324 (73.3) |

| Metabolic syndrome | 219 (49.5) |

| NAFLD fibrosis score | |

| < -1.455 | 244 (55.2) |

| -1.455-0.676 | 169 (38.2) |

| > 0.676 | 29 (6.6) |

| FIB4 index | |

| ≤ 1.31 | 323 (73.1) |

| 1.31-2.66 | 106 (24.0) |

| ≥ 2.67 | 13 (2.9) |

| BARD | |

| 0-1 | 163 (36.9) |

| 2-4 | 279 (63.1) |

| APRI | |

| ≤ 0.5 | 365 (82.6) |

| 0.51-1.5 | 73 (16.5) |

| > 1.5 | 4 (0.9) |

Among the CCHC participants from whom this sample was drawn (n = 1847), we previously reported that 67% were females, 39% had elevated ALT (≥ 40 U/L), and 44% had MetS[14]. Given the similarities between the current report and the previous report, we believe that the study cohort is representative of its parent cohort.

Table 2 shows the components and scoring for the diagnostic panels measured in the study. As shown in Table 2, a significant percentage of participants had elevated values on diagnostic panels suggesting the presence of NASH with fibrosis. The median (interquartile range) NFS value in the cohort was -1.63 (-2.57, -0.62). Based on published cut-off scores for the NFS[15], advanced liver fibrosis would be excluded in 55%, present in 7%, and indeterminate in 38% of the study participants. The median (interquartile range) FIB4 index in this cohort was 0.89 (0.58, 1.35). Similarly, based on published cut-off scores[9], advanced liver fibrosis would be excluded in 73%, present in 3% and indeterminate in 24% of the participants. The median (interquartile range) of the BARD score was 2 (1, 3). Using established cut-offs[8], 63% of the cohort would have been predicted to have advanced liver fibrosis. Finally, the median (interquartile range) of the APRI was 0.31 (0.21, 0.45). Using published cut-off values[10], advanced fibrosis would be excluded in 83%, present in 1% and indeterminate in 16% of the cohort. Based on these scores only 26% would have no predicted fibrosis and 0.4% would have predicted advanced fibrosis using all 4 panels. The majority of the cohort (73%) was predicted to have indeterminate risk for advanced liver fibrosis when using all 4 panels.

A comparison of two groups of study participants based on the presence or absence of hepatic steatosis on ultrasonography revealed the following results. As shown in Table 3, there was no difference in either age or gender between the two groups. However, the hepatic steatosis group had significantly higher BMI (32.9 ± 5.6 kg/m2vs 29.6 ± 6.1 kg/m2, P < 0.001) and higher prevalence rates of elevation of ALT (42.2% vs 14.6%, P < 0.001), elevation of AST (38.7% vs 18.9%, P < 0.001), and MetS (64.8% vs 33%, P < 0.001) than those without hepatic steatosis. In addition, features of MetS including central obesity (86.5% vs 59%, P < 0.001), hyperglycemia (41.7% vs 17.9%, P < 0.001), hypertriglyceridemia (47% vs 31.6%, P = 0.001), and lower HDL-C levels (70.4% vs 49.5%, P < 0.001) were significantly more common in participants with hepatic steatosis than those without hepatic steatosis. The NFS scores (P = 0.002) and the APRI scores (P = 0.002) were significantly higher in those with steatosis but the scores of the FIB4 index and BARD were similar between the two groups.

| Characteristics | Hepatic steatosis | P value | |

| Absent (n = 212) | Present (n = 230) | ||

| Age (yr) | 49.5 ± 16.3 | 48.7 ± 12.0 | 0.6 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 134 (63.2) | 156 (67.8) | |

| Male | 78 (36.8) | 74 (32.2) | 0.3 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.6 ± 6.1 | 32.9 ± 5.6 | < 0.001 |

| Elevated ALT1 | 31 (14.6) | 97 (42.2) | < 0.001 |

| Elevated AST2 | 40 (18.9) | 89 (38.7) | < 0.001 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.0 (3.8-4.2) | 4.0 (3.9-4.2) | 0.4 |

| Platelets (109/μL) | 237.5 (204.0-277.8) | 251.0 (214.0-283.5) | 0.1 |

| DM3 | 29 (13.7) | 68 (29.6) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 72 (34.0) | 95 (41.3) | 0.1 |

| Hyperglycemia | 38 (17.9) | 96 (41.7) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 67 (31.6) | 108 (47.0) | 0.001 |

| Low HDL-C | 105 (49.5) | 162 (70.4) | < 0.001 |

| Central obesity | 125 (59.0) | 199 (86.5) | < 0.001 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 70 (33.0) | 149 (64.8) | < 0.001 |

| NAFLD Fibrosis Score | |||

| < -1.455 | 134 (63.2) | 110 (47.8) | |

| -1.455-0.676 | 63 (29.7) | 106 (46.1) | |

| > 0.676 | 15 (7.1) | 14 (6.1) | 0.002 |

| FIB4 index | |||

| ≤ 1.3 | 157 (74.1) | 166 (72.2) | |

| 1.31-2.66 | 47 (22.2) | 59 (25.7) | |

| ≥ 2.67 | 8 (3.8) | 5 (2.2) | 0.46 |

| BARD | |||

| 0-1 | 79 (37.3) | 84 (36.5) | |

| 2-4 | 133 (62.7) | 146 (63.5) | 0.87 |

| APRI | |||

| ≤ 0.5 | 190 (89.6) | 175 (76.1) | |

| 0.51-1.5 | 22 (10.2) | 51 (22.2) | |

| > 1.5 | 0 (0) | 4 (1.7) | 0.0024 |

In univariable analysis, BMI [odds ratio (OR) = 1.11; 95%CI: 1.07-1.15, P < 0.0001], elevated ALT (OR = 4.26; 95%CI: 2.68-6.76, P < 0.0001), elevated AST (OR = 2.71; 95%CI: 1.76-4.19, P < 0.0001), MetS (OR= 3.73; 95%CI: 2.52-5.53, P < 0.0001) and its components including hyperglycemia (OR = 3.28; 95%CI: 2.12-5.08, P < 0.0001), hypertriglyceridemia (OR = 1.92; 95%CI: 1.30-2.83, P = 0.001), low HDL-C (OR = 2.43; 95%CI: 1.64-3.59, P < 0.0001), and central obesity (OR = 4.47; 95%CI: 2.80-7.13, P < 0.0001) were associated with fatty liver on ultrasound. Intermediate (OR = 2.05; 95%CI: 1.37-3.06, P = 0.0005) but not high NFS scores (OR = 1.14; 95%CI: 0.53-2.46, P = 0.74) were associated with ultrasonographic fatty liver. Similarly, intermediate (OR = 2.52; 95%CI: 1.47-4.32, P = 0.0008) were also associated with hepatic steatosis. Neither the FIB4 index nor the BARD was associated with fatty liver on ultrasound (Table 4).

| Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||||

| Characteristics | OR | 95%CI for OR | P value | OR1 | 95%CI for OR1 | P value |

| Age (yr) | 0.99 | 0.98-1.01 | 0.55 | |||

| Male gender | 0.81 | 0.55-1.21 | 0.31 | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1.11 | 1.07-1.15 | < 0.0001 | |||

| Elevated ALT1 | 4.26 | 2.68-6.76 | < 0.0001 | 4.04 | 2.50-6.52 | < 0.0001 |

| Elevated AST2 | 2.71 | 1.76-4.19 | < 0.0001 | 2.63 | 1.67-4.13 | < 0.0001 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 1.26 | 0.65-2.45 | 0.49 | 2.29 | 1.07-4.88 | 0.03 |

| Platelets (109/μL) | 1.00 | 0.99-1.01 | 0.14 | 1.00 | 0.99-1.00 | 0.55 |

| DM3 | 2.65 | 1.63-4.29 | 0.0001 | 2.22 | 1.31-3.77 | 0.003 |

| Hypertension | 1.37 | 0.93-2.01 | 0.11 | 1.18 | 0.72-1.82 | 0.45 |

| Hyperglycemia | 3.28 | 2.12-5.08 | < 0.0001 | 2.87 | 1.78-4.61 | < 0.0001 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 1.92 | 1.30-2.83 | 0.001 | 1.82 | 1.21-2.75 | 0.004 |

| Low HDL-C | 2.43 | 1.64-3.59 | < 0.0001 | 1.93 | 1.28-2.93 | 0.002 |

| Central obesity | 4.47 | 2.80-7.13 | < 0.0001 | 3.52 | 1.94-6.39 | < 0.0001 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 3.73 | 2.52-5.53 | < 0.0001 | 3.33 | 2.07-5.01 | < 0.0001 |

| NAFLD fibrosis score | ||||||

| < -1.455 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| -1.455-0.676 | 2.05 | 1.37-3.06 | 0.0005 | 1.83 | 1.10-3.04 | 0.02 |

| > 0.676 | 1.14 | 0.53-2.46 | 0.74 | 0.58 | 0.22-1.56 | 0.28 |

| FIB4 index | ||||||

| ≤ 1.3 | 1.00 | 1.004 | ||||

| 1.31-2.66 | 1.19 | 0.76-1.85 | 0.45 | 1.404 | 0.83-2.39 | 0.21 |

| ≥ 2.67 | 0.59 | 0.19-1.85 | 0.37 | 0.694 | 0.19-2.47 | 0.57 |

| BARD | ||||||

| 0-1 | 1.00 | 1.004 | ||||

| 2- 4 | 1.03 | 0.70-1.52 | 0.87 | 1.004 | 0.65-1.52 | 0.99 |

| APRI | ||||||

| ≤ 0.5 | 1.00 | 1.004 | ||||

| 0.51-1.5 | 2.52 | 1.47-4.32 | 0.0008 | 2.624 | 1.49-4.60 | 0.0008 |

| > 1.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

After adjusting for age, gender and BMI, elevated ALT (OR = 4.04; 95%CI: 2.50-6.52, P < 0.0001), elevated AST (OR = 2.63; 95%CI: 1.67-4.13, P < 0.0001), MetS (OR = 3.33; 95%CI: 2.07-5.01, P < 0.0001) and its components including hyperglycemia (OR = 2.87; 95%CI: 1.78-4.61, P < 0.0001), hypertriglyceridemia (OR = 1.82; 95%CI: 1.21-2.75, P = 0.004), low HDL-C (OR = 1.93; 95%CI: 1.28-2.93, P = 0.002) and central obesity (OR = 3.52; 95%CI: 1.94-6.39, P < 0.0001) remained as independent factors associated with hepatic steatosis in multivariable analysis. Similarly, intermediate but not high NFS scores (OR= 1.83; 95%CI: 1.10-3.04, P = 0.02) and APRI scores (OR = 2.62; 95%CI: 1.49-4.60, P = 0.0008) continued to be significantly associated with hepatic steatosis in multivariable analysis. Furthermore, serum albumin level became associated with hepatic steatosis in multivariable analysis (OR = 2.29; 95%CI: 1.07-4.88, P = 0.03) (Table 4).

This study is unique in examining community-recruited individuals from a population with multiple risk factors for NASH. The presumptive prevalence of liver fibrosis is startling particularly since our sampling methods avoided the bias of studies from specialized clinics. The potential disease burden of advanced liver disease in these Mexican Americans is of great public health concern.

To reach these conclusions we assessed the potential burden of NASH and advanced fibrosis in our participants utilizing four noninvasive diagnostic panels. We found that 52% of all individuals had evidence of hepatic steatosis and thereby NAFLD, in line with the high prevalence of elevated BMI, abnormal aminotransferase levels and MetS in the cohort. Based on established cut-offs for the diagnostic panels, we found that between 17%-63% of the cohort would be predicted to have NASH with indeterminate or advanced fibrosis, depending on the method used. Evidence of the potential burden of hepatic disease was seen both in those with and without steatosis on ultrasound. However, the severity of the NFS and APRI scores were higher in those with steatosis. These findings, although imprecise, support the hypothesis that the burden of NAFLD related diseases in Mexican Americans on the south Texas border may be even greater than anticipated from published studies. Our data underscore the need to directly assess hepatic histology from the high risk participants we identified in order to validate more precise non-invasive diagnostic panels and to determine the need and targets for therapeutic interventions and prevention.

Our observation that 52% of a population-based Mexican American cohort has NAFLD by ultrasound extends our prior work and substantiates studies where Hispanic individuals were recruited from primary care and gastroenterology clinics from military facilities[16]. This burden of disease parallels the high prevalence of obesity, diabetes and lipid abnormalities in these populations. We may in fact have underestimated the true overall prevalence of advancing liver disease since we were limited in this study to ultrasonography which is not the most sensitive means of detecting liver fat[5]. This is likely, since, many of the individuals who did not have steatosis on ultrasound did have multiple risk factors for NAFLD. It is likely that lesser degrees of steatosis were not appreciated. The fact that our individuals represent a health disparity cohort with diminished access to health care magnifies the potential clinical consequences of NAFLD. This is a population that has little access to therapy for underlying conditions that contribute to liver fat and inflammation.

We were constrained to use a noninvasive approach to explore the potential burden of NASH and advanced fibrosis in this cohort, since at this stage we could not justify liver biopsy. Our participants are recruited from households and are not aware of their disease. However, given the striking findings in this small pilot sample, we now need to validate the non-invasive markers so that population based screening for early liver disease becomes feasible in high risk populations.

The series of panels, comprised of common, easily available anthropometric, hematologic and biochemical parameters were chosen based on published studies and practice guidelines supporting utility in detecting or excluding advanced fibrosis in NASH or Hepatitis C induced liver disease[7]. The NFS score (n = 733)[15], the FIB4 index (n = 541)[9], and the BARD score (n = 827)[8] were derived from largely Caucasian cohorts who underwent liver biopsy during evaluation for NAFLD. The APRI (n = 270) was derived from a cohort of patients with chronic hepatitis C who underwent biopsy[10]. Twenty to 50% of individuals in these cohorts had advanced fibrosis by biopsy and the scoring systems were useful in identifying these individuals. Applied in our cohort, the NFS, FIB4 and BARD scores predicted that between 24%-38% have indeterminate and up to 63% have high probability of NASH with advanced fibrosis. The APRI predicted 17% with indeterminate or advanced fibrosis. This high percentage of indeterminate or advanced fibrosis (73%) is surprising in a community based cohort without prior history of liver diseases. However, only the intermediate NFS and APRI scores between published low and high cut-offs correlated directly with the presence of steatosis by ultrasonography. The lack of significant association between the NFS or APRI scores higher than published high cut-off values and hepatic steatosis could be due to “burn-out” NASH as advanced liver fibrosis in NASH is often accompanied by a reduction in hepatic fat to the point of complete fat loss[17]. Alternatively, the lack of association might be attributed to type II error due to the small number of participants who had high NFS or APRI scores. Nonetheless, the values of these scores demonstrate the need to accurately define the prevalence of advanced fibrosis in this cohort.

There are several limitations in this study. First, hepatic steatosis was detected by ultrasonography, which has decreased sensitivity with lower degrees of steatosis[5]. This approach could have resulted in misclassification of some patients with mild steatosis as having no steatosis, thereby contributing to the imprecision in diagnostic scores. However, ultrasonography is the standard technique for detecting steatosis in large clinical trials and we prospectively performed imaging in consecutive well phenotyped participants with extensive clinical and biochemical data. The observation that over 50% of our community based cohort has steatosis despite the sensitivity limitations of ultrasound attests to the frequency of disease. In support of this we were able to utilized noninvasive panels to predict the potential burden of disease without histology. Our data are useful since these panels have been advocated for use in identifying patients at significantly increased risk for advanced fibrosis to target or avoid biopsy, respectively, and their utility in population screening has not been determined[6]. Though the potential burden of advancing liver disease looks to be high, variability and lack of concordance between panels underscore the imprecision in these measures. Our data provide a strong rationale for proceeding to liver biopsy in a sample of these individuals most at risk to directly define disease burden and to further evaluate the utility of noninvasive diagnostic strategies.

In conclusion, in this community-based study of asymptomatic Hispanics, we found a surprisingly high potential burden of NASH and advanced fibrosis. We further found that commonly used diagnostic panels employing published cut-offs, are imprecise as predictors of steatosis and NASH. We document an urgent need to identify accessible and useful screening modalities for population-based studies in Hispanics so that we can develop targeted preventive and therapeutic measures. In short, community-based prospective studies in Hispanics which include liver histology will be needed.

We thank our cohort recruitment team, particularly Rocio Uribe, Julie Gomez-Ramirez and Jody Rodriguez. We also thank Marcela Montemayor and laboratory staff for their contribution, Israel Hernandez and Pablo Sanchez for our database management and Christina Villarreal for administrative support. We thank Valley Baptist Medical Center, Brownsville for providing us space for our Center for Clinical and Translational Science Clinical Research Unit. We finally thank the community of Brownsville and the participants who so willingly participated in this study in their city.

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is found in up to 20% of hispanics evaluated for hepatic abnormalities but the true prevalence in hispanic communities remains unknown.

Markers that either individually or as composite panels predict the presence of NASH and advanced fibrosis of liver have been developed. These biomarkers and panels have been validated in cross-sectional studies of non-hispanic cohorts evaluated for liver abnormalities but have not been evaluated in a population setting in Hispanics.

In this population-based cohort study, the authors assessed four diagnostic panels for NASH and fibrosis in asymptomatic individuals enrolled in the Cameron County Hispanic Cohort. Based on established cut-offs for diagnostic panels, between 17%-63% of the entire cohort was predicted to have NASH with indeterminate or advanced fibrosis.

The burden of NASH and advanced fibrosis in the Hispanic community in South Texas may be more substantial than predicted from referral clinic studies. Delineation of the true prevalence of disease and validation of non-invasive diagnostic markers in this high risk population will require prospective correlation with liver histology.

The nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) fibrosis score, the FIB4 index, the BARD score, and the aspartate aminotransferase to Platelet Ratio Index are non-invasive diagnostic panels that are derived from common anthropometric, hematological and biochemical parameters and are used to predict advanced fibrosis in NAFLD.

The study by Pan et al highlights the burden of NAFLD within a well defined population within the United States (viz the Cameron County Hispanic Cohort). The study is essentially a hypothesis generating piece of research that the researchers acknowledge requires prospective follow-up with liver histology.

P- Reviewer: Butterworth J, Conte D S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | de Alwis NM, Day CP. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: the mist gradually clears. J Hepatol. 2008;48 Suppl 1:S104-S112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 397] [Cited by in RCA: 419] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Angulo P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1221-1231. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Pan JJ, Fallon MB. Gender and racial differences in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Hepatol. 2014;6:274-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Ennis SR, Rios-Vargas M, Albert NG. The Hispanic population: 2010. 2010 Census brief. 2011;. |

| 5. | Wieckowska A, McCullough AJ, Feldstein AE. Noninvasive diagnosis and monitoring of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: present and future. Hepatology. 2007;46:582-589. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Pearce SG, Thosani NC, Pan JJ. Noninvasive biomarkers for the diagnosis of steatohepatitis and advanced fibrosis in NAFLD. Biomark Res. 2013;1:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Diehl AM, Brunt EM, Cusi K, Charlton M, Sanyal AJ. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Gastroenterological Association. Hepatology. 2012;55:2005-2023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2413] [Cited by in RCA: 2646] [Article Influence: 189.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 8. | Harrison SA, Oliver D, Arnold HL, Gogia S, Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Development and validation of a simple NAFLD clinical scoring system for identifying patients without advanced disease. Gut. 2008;57:1441-1447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 545] [Cited by in RCA: 648] [Article Influence: 36.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shah AG, Lydecker A, Murray K, Tetri BN, Contos MJ, Sanyal AJ. Comparison of noninvasive markers of fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1104-1112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1205] [Cited by in RCA: 1229] [Article Influence: 72.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, Kalbfleisch JD, Marrero JA, Conjeevaram HS, Lok AS. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518-526. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Fisher-Hoch SP, Rentfro AR, Salinas JJ, Pérez A, Brown HS, Reininger BM, Restrepo BI, Wilson JG, Hossain MM, Rahbar MH. Socioeconomic status and prevalence of obesity and diabetes in a Mexican American community, Cameron County, Texas, 2004-2007. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7:A53. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Hamaguchi M, Kojima T, Itoh Y, Harano Y, Fujii K, Nakajima T, Kato T, Takeda N, Okuda J, Ida K. The severity of ultrasonographic findings in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease reflects the metabolic syndrome and visceral fat accumulation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2708-2715. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001;285:2486-2497. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Pan JJ, Qu HQ, Rentfro A, McCormick JB, Fisher-Hoch SP, Fallon MB. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and risks of abnormal serum alanine aminotransferase in Hispanics: a population-based study. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Angulo P, Hui JM, Marchesini G, Bugianesi E, George J, Farrell GC, Enders F, Saksena S, Burt AD, Bida JP. The NAFLD fibrosis score: a noninvasive system that identifies liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Hepatology. 2007;45:846-854. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Cusi K, Chang Z, Harrison S, Lomonaco R, Bril F, Orsak B, Ortiz-Lopez C, Hecht J, Feldstein AE, Webb A. Limited value of plasma cytokeratin-18 as a biomarker for NASH and fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2014;60:167-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | van der Poorten D, Samer CF, Ramezani-Moghadam M, Coulter S, Kacevska M, Schrijnders D, Wu LE, McLeod D, Bugianesi E, Komuta M. Hepatic fat loss in advanced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: are alterations in serum adiponectin the cause? Hepatology. 2013;57:2180-2188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |