Published online Sep 27, 2014. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v6.i9.670

Revised: July 16, 2014

Accepted: August 27, 2014

Published online: September 27, 2014

Processing time: 155 Days and 23.6 Hours

AIM: To study the relationship between adverse events (AEs), efficacy, and nursing intervention for sorafenib therapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

METHODS: We enrolled 37 consecutive patients with advanced HCC who received sorafenib therapy. Relationships among baseline characteristics as well as AE occurrence and tumor response, overall survival (OS), and treatment duration were analyzed. The nursing intervention program consisted of education regarding self-monitoring and AEs management, and telephone follow-up was provided once in 1-2 wk.

RESULTS: A total of 37 patients were enrolled in the study, comprising 30 males (81%) with a median age of 71 years. The disease control rate at 3 mo was 41%, and the median OS and treatment duration were 259 and 108 d, respectively. Nursing intervention was given to 24 patients (65%). Every patient exhibited some kinds of AEs, but no patients experienced G4 AEs. Frequently observed AEs > G2 included anorexia (57%), skin toxicity (57%), and fatigue (54%). Factors significantly associated with longer OS in multivariate analysis demonstrated that age ≤ 70 years, presence of > G2 skin toxicity, and absence of > G2 hypoalbuminemia. The disease control rate in patients with > G2 skin toxicity was 13/20 (65%), which was significantly higher compared with that in patients with no or G1 skin toxicity. Multivariate analysis revealed that nursing intervention and > G2 skin toxicity were independent significant predictors for longer treatment duration.

CONCLUSION: Skin toxicity was associated with favorable outcomes with sorafenib therapy for advanced HCC. Nursing intervention contributed to better adherence, which may improve the efficacy of sorafenib.

Core tip: Sorafenib therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) often causes adverse events (AEs), subsequently leading to dose reduction or discontinuation. Conversely, few studies have associated serious AEs with a favorable response to sorafenib. We aimed to elucidate the relationship between AEs occurrence, therapeutic efficacy, and the impact of nursing intervention on adherence to therapy. We observed that skin toxicity was associated with favorable outcomes in sorafenib therapy for advanced HCC. Furthermore nursing intervention contributed to better adherence, which may improve the efficacy of sorafenib therapy.

- Citation: Shomura M, Kagawa T, Shiraishi K, Hirose S, Arase Y, Koizumi J, Mine T. Skin toxicity predicts efficacy to sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol 2014; 6(9): 670-676

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v6/i9/670.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v6.i9.670

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide[1,2]; in addition, it is one of the intractable cancers, considering its high rate of recurrence even after curative therapies[3]. In particular, vascular invasion and extrahepatic metastasis greatly decrease survival rates[4-8].

Sorafenib, an oral inhibitor, is currently used as a standard therapeutic option for advanced HCC[9-11]. This drug occasionally causes severe adverse events (AEs), which include hand-foot skin reaction (HFSR), hypertension, diarrhea, anorexia, fatigue, weight loss, and so on. Although most AEs are reversible, they can significantly impact a patient’s quality of life and occasionally result in dose reduction or discontinuation of therapy[12]. On the other hand, recent studies of sorafenib therapy for HCC have reported that the occurrence of any grade (G) hypertension[13] or > G2 diarrhea[14] was associated with longer overall survival (OS); in addition, skin toxicity resulted in preferable outcomes as well[15,16]. However, studies investigating the relationship between AEs occurrence and efficacy of this drug remain insufficient.

The increase of available oral anticancer drugs has introduced a shift in responsibility from clinicians to patients and their families for self-administration of these drugs and AEs management. Reduced adherence leads to poor clinical outcomes and subsequent increase in healthcare costs[17,18]. Several studies have suggested that an adequate intervention by nurses and pharmacists may improve treatment adherence[19-22]. However, the contribution of nursing intervention to treatment adherence remains elusive.

This study aimed to elucidate the relationship between AEs occurrence and the efficacy of sorafenib therapy for patients with advanced HCC. In addition, we evaluated the impact of nursing intervention on the adherence to this drug therapy.

This work has been carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2000) of the World Medical Association. This study was approved ethically by the Institutional Review Board of Tokai University (NO.10R-046). All patients provided informed written consents.

We enrolled consecutive patients with advanced HCC who received sorafenib therapy from August 2009 to December 2012 at Tokai University Hospital. Eligibility criteria were as follows: (1) unresectable advanced HCC; (2) resistance to or no indication of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE); (3) Child-Pugh class A or B; and (4) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status of 0 or 1. Patients received 800 mg sorafenib as an initial daily dose. However, lower doses were occasionally selected by doctors, particularly when patients were aged > 70 years or had liver function of Child-Pugh class B. The HCC stage was classified according to the tumor-node-metastasis criteria of the Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan[23].

The nursing intervention program consisted of education regarding self-monitoring and AEs management, and telephone follow-up was provided once in 1-2 wk[24,25]. One nurse who experienced and trained specialized care with liver cancer patients provided the nursing intervention.

Efficacy was evaluated according to the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors[26] 3 mo after the initiation of therapy. Thereafter, dynamic computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed every 3 mo. The disease control rate was defined as the percentage of patients with complete response (CR), partial response (PR), and stable disease (SD). AEs were assessed according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Effects, version 4.0[27]. Skin toxicity included HFSR and any kind of rash. Patients were followed up until January 7, 2013 or death.

Relationships of efficacy to baseline patient characteristics and AEs occurrence were evaluated using Fisher’s exact probability test or multiple logistic regression analysis. Further, OS and treatment duration were analyzed using the log-rank test or Cox proportional hazards regression model. Multivariate analyses were performed using the stepwise (step-up) procedure (likelihood ratio). All variables with P values < 0.15 in univariate analysis were included for multivariate analysis. P values < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical package IBM® SPSS® Statistics version 21 for Windows (1989, Somers, NY).

| Variables | Number of patients | |

| Gender | Male | 30 (81) |

| Female | 7 (19) | |

| Age (yr) | > 70 | 19 (51) |

| ≤ 70 | 18 (49) | |

| Child-pugh class | A | 33 (89) |

| B | 4 (11) | |

| Etiology | HCV | 20 (54) |

| HBV | 11 (30) | |

| Others | 6 (16) | |

| TNM stage | III | 16 (43) |

| IVa | 8 (22) | |

| IVb | 13 (35) | |

| Previous therapies | Yes | 31 (84) |

| No | 6 (16) | |

| AFP (ng/mL) | > 100 | 20 (54) |

| ≤ 100 | 17 (46) | |

| DCP (mAU/mL)a | > 1000 | 20 (59) |

| ≤ 1000 | 14 (41) | |

| Initial dose of sorafenib (mg/d) | 800 | 21 (57) |

| < 800 | 16 (43) | |

| Nursing intervention | Yes | 24 (65) |

| No | 13 (35) | |

A total of 37 patients were enrolled in the study, comprising 30 males (81%) with a median age of 71 years (range, 36-83 years). More than half of the patients (54%) were infected with hepatitis C virus. Most patients (84%) had received other treatment for HCC before sorafenib therapy, including surgical resection, TACE, and radiofrequency ablation. Sixteen patients (43%) received < 800 mg sorafenib as an initial daily dose. Nursing intervention was given to 24 patients (65%).

Disease control was obtained in 15 patients (41%) comprising 1 (3%) with CR, 3 (8%) with PR, and 11 (30%) with SD at 3 mo after the initiation of sorafenib therapy. The patient who achieved CR was a 69-year-old male patient, a noteworthy case that has also been reported elsewhere[28]. He received sorafenib at a dose of 800 mg for HCC metastasis to a portal lymph node metastasis that appeared 3 years after surgical resection for primary HCC. However, he discontinued sorafenib administration after 11 d because of G3 HFSR. Despite treatment termination, the portal lymph node metastasis disappeared along with the normalization of serum (des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin) DCP (and α-fetoprotein) AFP levels. A total of 27 patients (73%) died. One patient was lost to follow-up. The median OS period was 259 d (range, 41-664 d).

| Adverse events | Any Grade | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 |

| Anorexia | 29 (78) | 8 (22) | 10 (27) | 11 (30) |

| Skin toxicitya | 27 (73) | 6 (16) | 8 (22) | 13 (35) |

| Fatigue | 23 (62) | 3 ( 8) | 11 (30) | 9 (24) |

| Diarrhea | 20 (54) | 9 (24) | 8 (21) | 3 (8) |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 19 (51) | 4 (11) | 14 (38) | 1 (3) |

| Weight loss | 17 (46) | 7 (19) | 9 (24) | 1 (3) |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 16 (43) | 10 (27) | 5 (14) | 1 (3) |

| Decreased platelet count | 14 (38) | 3 (8) | 9 (24) | 2 (5) |

| Hypertension | 13 (35) | 2 (5) | 6 (16) | 5 (14) |

| Alopecia | 13 (35) | 5 (14) | 8 (22) | 0 (0) |

| Anemia | 9 (24) | 4 (11) | 4 (11) | 1 (3) |

Every patient exhibited some kind of AEs, but no patient experienced G4 AEs. Frequently observed > G2 AEs included anorexia (57%), skin toxicity (57%), fatigue (54%), hypoalbuminemia (41%), and hypertension (30%). Sorafenib therapy was discontinued in 5 patients (14%) because of skin toxicity (n = 4) and anorexia (n = 1). Fifteen patients (41%) required dose reduction because of skin toxicity (n = 8), anorexia (n = 4), hyperbilirubinemia (n = 2), and hypertension (n = 1).

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

| HR(95%CI) | P value | HR(95%CI) | P value | |

| Gender, male (vs female) | 0.384 (0.147-1.005) | 0.051 | ||

| Age, ≤ 70 yr (vs > 70 yr) | 0.491 (0.225-1.071) | 0.074 | 0.354 (0.135-0.933) | 0.036 |

| Previous therapy yes (vs no) | 0.035 (0.128-0.961) | 0.042 | ||

| DCP, ≤ 1000 mAU/mL (vs > 1000 mAU/mL) | 0.416 (0.178-0.974) | 0.043 | ||

| Initial dose of sorafenib, 800 mg (vs < 800 mg) | 0.405 (0.185-0.888) | 0.024 | ||

| Adverse events > grade 2 | ||||

| Anorexia - (vs +) | 0.374 (0.158-0.888) | 0.026 | ||

| Skin toxicitya + (vs -) | 0.278 (0.122-0.635) | 0.002 | 0.267 (0.102-0.701) | 0.007 |

| Fatigue - (vs +) | 0.404 (0.176-0.924) | 0.032 | ||

| Hypoalbuminemia - (vs +) | 0.379 (0.170-0.842) | 0.017 | 0.221 (0.085-0.575) | 0.002 |

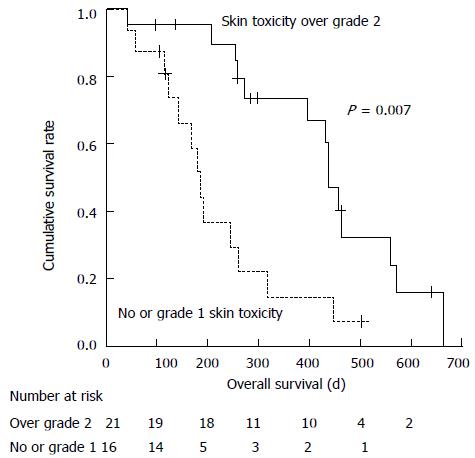

Factors significantly associated with longer OS in univariate analysis included the presence of previous therapy, serum DCP levels ≤ 1000 mAU/mL, 800 mg initial sorafenib dose, absence of > G2 anorexia, fatigue or hypoalbuminemia, and presence of > G2 skin toxicity. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that age ≤ 70 years (HR = 0.354, 95%CI: 0.135-0.933; P = 0.036), presence of > G2 skin toxicity (Figure 1, HR = 0.267, 95%CI: 0.102-0.701; P = 0.007), and absence of > G2 hypoalbuminemia (HR = 0.221, 95%CI: 0.085-0.575; P = 0.002) were significant predictors for longer OS. The disease control rate in patients with > G2 skin toxicity was 13/20 (65%), which was significantly higher compared with that in patients with no or G1 skin toxicity [2/17 (12%); P = 0.002].

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age ≤ 70 yr (vs > 70 yr) | 0.543 (0.257-1.147) | 0.110 | ||

| Other etiologies (vs HCV infection) | 0.411 (0.191-0.886) | 0.023 | ||

| DCP ≤ 1000 mAU/mL (vs > 1000 mAU/mL) | 0.402 (0.190-0.851) | 0.017 | ||

| Nursing intervention yes (vs no) | 0.577 (0.278-1.198) | 0.140 | 0.398 (0.181-0.874) | 0.022 |

| Efficacy, disease control (vs PD) | 0.431 (0.206-0.903) | 0.026 | ||

| Adverse events > grade 2 + (vs -) | ||||

| Skin toxicitya | 0.306 (0.139-0.675) | 0.003 | 0.225 (0.095-0.534) | 0.001 |

| Diarrhea | 0.352 (0.156-0.796) | 0.012 | ||

| Weight loss | 0.555 (0.254-1.213) | 0.140 | ||

| Alopecia | 0.236 (0.081-0.686) | 0.008 | ||

The median duration of medication was 108 d (range, 4-462 d). A total of 33 patients (89%) discontinued sorafenib: 18 (55%) for deterioration of general status, 10 (30%) for the lack of beneficial effects of sorafenib, and 5 (15%) for G3 AEs.

We provided face-to-face counseling 1-2 times per mo and telephone follow-up once in 1-2 wk to manage AEs by supporting patient’s self-monitoring and self-care[24,25]. Multivariate analysis revealed that nursing intervention (HR = 0.398, 95%CI: 0.181-0.874; P = 0.022) and > G2 skin toxicity (HR = 0.225, 95%CI: 0.095-0.534; P = 0.001) were independent significant predictors for longer treatment duration. Median treatment durations were 122 and 36 d in patients with and without nursing intervention, respectively. However, nursing intervention was not associated with OS, with the median OS being 258 and 274 d for patients with and without nursing intervention, respectively.

In this study, the median OS was 8.6 mo, which is comparable to previous studies: 10.7, 6.5, and 9.3 mo in the SHARP trial[9], the Asia-Pacific study[10], and the Global Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology Network study[29], respectively. The disease control rate was 41%, which was lower compared with that in the abovementioned studies, ranging from 57%[10] to 73%[9]. This difference may be attributable to the timing of tumor evaluation; CT or MRI was performed 3 and 1.5 mo after the initiation of sorafenib in the present and abovementioned studies, respectively. AEs were observed in all patients. Similar to previous studies, frequently observed AEs included anorexia, skin toxicity, fatigue, and diarrhea[9-11,29,30].

Multivariate analysis indicated that age ≤ 70 years, presence of > G2 skin toxicity, and absence of > G2 hypoalbuminemia were significant predictors of longer OS. HR of patients aged ≤ 70 years against older patients was 0.35. The Asia-Pacific study reported that a beneficial effect of sorafenib was obtained only in patients aged < 65 years[10]. Therefore, an elderly patient aged > 70 years with advanced HCC may not be a good candidate for this therapy.

We demonstrated that the occurrence of skin toxicity was associated with a higher disease control rate (65% vs 12%; P = 0.002) and longer OS (HR = 0.267). These results are in concordance with those of previous studies[15,16]. Sorafenib exerts anticancer effects by inhibiting the serine–threonine kinases Raf-1 (c-Raf) and B-Raf, and the receptor tyrosine kinase activity of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFRs) 1, 2, and 3 and platelet-derived growth factor receptor α[31]. Nevertheless, mechanisms underlying skin toxicity induced by this drug remain largely unknown. Recent studies demonstrated that genetic polymorphisms of VEGF[32] and VEGFR2[33] were related to the occurrence of HFSR, suggesting the involvement of VEGF signaling. Patients with a genetic predisposition to HFSR may be more sensitive to the antitumor effects of sorafenib. Further research regarding the contribution of genetic variation to skin toxicity and efficacy in this therapy is clearly required.

Other studies reported that the occurrence of hypertension[13] or diarrhea[14] was related to favorable clinical outcomes. However, we could not confirm these results in our study.

In our study, hypoalbuminemia was related to poor prognosis; this can be interpreted as a sign of progression of liver disease. In previous sorafenib studies, patients with lower pretreatment serum albumin levels had a greater risk of treatment discontinuation[28] and poor prognosis[29,34].

Because skin toxicity was associated with better prognosis, controlling this AE potentially offers benefit to patients. Moisturizers, sunscreen creams, steroid ointments, and oral antibiotics such as doxycycline can effectively prevent skin toxicity[35,36]. In particular, applying moisturizers before initiation of sorafenib therapy and avoiding stimulation to palms and soles are important[36].

In this study, we observed that nursing intervention significantly extended the treatment duration. Our nursing intervention program consisted of education on self-monitoring and AEs management and telephone follow-up. Improved management of AEs or removal of anxiety by telephone follow-up may contribute to these results. The importance of patient and family education and continuity of care along with the increasing use of oral anticancer drugs has been reaffirmed in previous studies[25]. However, the impact of nursing intervention on adherence or AEs management remains elusive. Nurse-led telephone follow-up for patients receiving oral capecitabine resulted in decreased occurrence of AEs compared with historical data[37]. On the other hand, a randomized controlled trial evaluating the role of nursing intervention in symptom management and treatment adherence for patients, who were prescribed oral chemotherapy agents, could not verify its efficacy[22]. Therefore, further studies in this regard are warranted. This study has limitations. This was a retrospective study, with a relatively small number of patients from a single institution.

In conclusion, our study revealed that skin toxicity may be a surrogate marker for preferable effects of sorafenib in the management of advanced HCC. Moreover, nursing intervention significantly contributed to treatment adherence. Establishment of better nursing intervention programs that can maintain adherence by controlling serious AEs is important in maximizing the efficacy of this oral anticancer drug.

We express our thanks to all patients who took part in this clinical research. We thank all the members of Department of Nursing of Tokai University Hospital for discussion and comments.

Sorafenib therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) often causes adverse events (AEs), subsequently leading to dose reduction or discontinuation. Conversely, a few studies have associated serious AEs with a favorable response. Contributes of nursing intervention on treatment adherence to therapy were unclear.

In this study, the authors revealed that skin toxicity may be a surrogate marker for preferable effects of sorafenib in the management of advanced HCC. Moreover, nursing intervention significantly contributed to treatment adherence. Establishment of better nursing intervention programs that can maintain adherence by controlling serious AEs is important in maximizing the efficacy of this oral anticancer drug.

The authors demonstrated that the occurrence of skin toxicity was associated with a higher disease control rate (65% vs 12%; P = 0.002) and longer overall survival [hazard ratio: 0.267). These results are in concordance with those of previous studies. In this study, hypoalbuminemia was related to poor prognosis; this can be interpreted as a sign of progression of liver disease. In this study, hypoalbuminemia was related to poor prognosis; this can be interpreted as a sign of progression of liver disease. In previous sorafenib studies, patients with lower pretreatment serum albumin levels had a greater risk of treatment discontinuation and poor prognosis. This nursing intervention program consisted of education on self-monitoring and AEs management and telephone follow-up. Improved management of AEs or removal of anxiety by telephone follow-up may contribute to these results.

This study revealed that skin toxicity may be a surrogate marker for preferable effects of sorafenib in the management of advanced HCC. Moreover, nursing intervention significantly contributed to treatment adherence. Establishment of better nursing intervention programs that can maintain adherence by controlling serious AEs is important in maximizing the efficacy of this oral anticancer drug.

Sorafenib, an oral multikinase inhibitor, is currently used as a standard therapeutic option for advanced HCC. Sorafenib exerts anticancer effects by inhibiting the serine-threonine kinases Raf-1 (c-Raf) and B-Raf, and the receptor tyrosine kinase activity of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptors 1, 2, and 3 and platelet-derived growth factor receptor â.

In this study, the authors reported that significant skin toxicity(> grade 2), yourger age (< 70 years), and absence of hypoalbuminemia were associated with better overall survival. Significant skin toxicity and nursing intervention were associated with longer treatment duration. This paper refers to skin toxicity as predictor of efficacy to sorafenib in patients with advanced HCC. The paper is of interest since it gives important clues for better selection of patients who may benefit at best from treatment with sorafenib.

| 1. | Gomaa AI, Khan SA, Toledano MB, Waked I, Taylor-Robinson SD. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology, risk factors and pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4300-4308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 456] [Cited by in RCA: 502] [Article Influence: 27.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (14)] |

| 2. | Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23762] [Cited by in RCA: 25606] [Article Influence: 1707.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (11)] |

| 3. | Ochiai T, Ikoma H, Okamoto K, Kokuba Y, Sonoyama T, Otsuji E. Clinicopathologic features and risk factors for extrahepatic recurrences of hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. World J Surg. 2012;36:136-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5972] [Cited by in RCA: 6630] [Article Influence: 442.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Kudo M, Izumi N, Kokudo N, Matsui O, Sakamoto M, Nakashima O, Kojiro M, Makuuchi M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan: Consensus-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines proposed by the Japan Society of Hepatology (JSH) 2010 updated version. Dig Dis. 2011;29:339-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 642] [Cited by in RCA: 677] [Article Influence: 45.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kokudo N, Nakajima J, Hatano E, Numata K. Current status of hepatocellular carcinoma treatment in Japan: practical use of sorafenib (Nexavar®). Clin Drug Investig. 2012;32 Suppl 2:25-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | European Association for Study of Liver; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:599-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 307] [Cited by in RCA: 368] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Verslype C, Rosmorduc O, Rougier P. Hepatocellular carcinoma: ESMO-ESDO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23 Suppl 7:vii41-vii48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 283] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul JL, Forner A. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9016] [Cited by in RCA: 10533] [Article Influence: 585.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 10. | Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, Luo R, Feng J, Ye S, Yang TS. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3854] [Cited by in RCA: 4740] [Article Influence: 263.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nakano M, Tanaka M, Kuromatsu R, Nagamatsu H, Sakata K, Matsugaki S, Kajiwara M, Fukuizumi K, Tajiri N, Matsukuma N. Efficacy, safety, and survival factors for sorafenib treatment in Japanese patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology. 2013;84:108-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhang X, Yang XR, Huang XW, Wang WM, Shi RY, Xu Y, Wang Z, Qiu SJ, Fan J, Zhou J. Sorafenib in treatment of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2012;11:458-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Estfan B, Byrne M, Kim R. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: hypertension as a potential surrogate marker for efficacy. Am J Clin Oncol. 2013;36:319-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Koschny R, Gotthardt D, Koehler C, Jaeger D, Stremmel W, Ganten TM. Diarrhea is a positive outcome predictor for sorafenib treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology. 2013;84:6-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Vincenzi B, Santini D, Russo A, Addeo R, Giuliani F, Montella L, Rizzo S, Venditti O, Frezza AM, Caraglia M. Early skin toxicity as a predictive factor for tumor control in hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with sorafenib. Oncologist. 2010;15:85-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Otsuka T, Eguchi Y, Kawazoe S, Yanagita K, Ario K, Kitahara K, Kawasoe H, Kato H, Mizuta T. Skin toxicities and survival in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with sorafenib. Hepatol Res. 2012;42:879-886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Senst BL, Achusim LE, Genest RP, Cosentino LA, Ford CC, Little JA, Raybon SJ, Bates DW. Practical approach to determining costs and frequency of adverse drug events in a health care network. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001;58:1126-1132. [PubMed] |

| 18. | McDonnell PJ, Jacobs MR. Hospital admissions resulting from preventable adverse drug reactions. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:1331-1336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 354] [Cited by in RCA: 341] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;CD000011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 306] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Decker V, Spoelstra S, Miezo E, Bremer R, You M, Given C, Given B. A pilot study of an automated voice response system and nursing intervention to monitor adherence to oral chemotherapy agents. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32:E20-E29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Given BA, Spoelstra SL, Grant M. The challenges of oral agents as antineoplastic treatments. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2011;27:93-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Spoelstra SL, Given BA, Given CW, Grant M, Sikorskii A, You M, Decker V. An intervention to improve adherence and management of symptoms for patients prescribed oral chemotherapy agents: an exploratory study. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36:18-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Minagawa M, Ikai I, Matsuyama Y, Yamaoka Y, Makuuchi M. Staging of hepatocellular carcinoma: assessment of the Japanese TNM and AJCC/UICC TNM systems in a cohort of 13,772 patients in Japan. Ann Surg. 2007;245:909-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hartigan K. Patient education: the cornerstone of successful oral chemotherapy treatment. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2003;7:21-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Neuss MN, Polovich M, McNiff K, Esper P, Gilmore TR, LeFebvre KB, Schulmeister L, Jacobson JO. 2013 updated American Society of Clinical Oncology/Oncology Nursing Society chemotherapy administration safety standards including standards for the safe administration and management of oral chemotherapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40:225-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:52-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3353] [Cited by in RCA: 3441] [Article Influence: 215.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (43)] |

| 27. | Japan Clinical Oncology Group. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v4.0-Japan Clinical Oncology Group. Available from: http://www.jcog.jp/doctor/tool/ctcaev4.html, 2013 (accessed Jul 29, 2013). |

| 28. | Mizukami H, Kagawa T, Arase Y, Nakahara F, Tsuruya K, Anzai K, Hirose S, Shiraishi K, Shomura M, Koizumi J. Complete response after short-term sorafenib treatment in a patient with lymph node metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Case Rep Oncol. 2012;5:380-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lencioni R, Kudo M, Ye SL, Bronowicki JP, Chen XP, Dagher L, Furuse J, Geschwind JF, Ladrón de Guevara L, Papandreou C. First interim analysis of the GIDEON (Global Investigation of therapeutic decisions in hepatocellular carcinoma and of its treatment with sorafeNib) non-interventional study. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66:675-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Iavarone M, Cabibbo G, Piscaglia F, Zavaglia C, Grieco A, Villa E, Cammà C, Colombo M. Field-practice study of sorafenib therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective multicenter study in Italy. Hepatology. 2011;54:2055-2063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 287] [Cited by in RCA: 300] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wilhelm SM, Adnane L, Newell P, Villanueva A, Llovet JM, Lynch M. Preclinical overview of sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor that targets both Raf and VEGF and PDGF receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:3129-3140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1149] [Cited by in RCA: 1142] [Article Influence: 63.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lee JH, Chung YH, Kim JA, Shim JH, Lee D, Lee HC, Shin ES, Yoon JH, Kim BI, Bae SH. Genetic predisposition of hand-foot skin reaction after sorafenib therapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2013;119:136-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Jain L, Sissung TM, Danesi R, Kohn EC, Dahut WL, Kummar S, Venzon D, Liewehr D, English BC, Baum CE. Hypertension and hand-foot skin reactions related to VEGFR2 genotype and improved clinical outcome following bevacizumab and sorafenib. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2010;29:95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Morimoto M, Numata K, Moriya S, Kondo M, Nozaki A, Morioka Y, Maeda S, Tanaka K. Inflammation-based prognostic score for hepatocellular carcinoma patients on sorafenib treatment. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:619-623. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Lacouture ME, Mitchell EP, Piperdi B, Pillai MV, Shearer H, Iannotti N, Xu F, Yassine M. Skin toxicity evaluation protocol with panitumumab (STEPP), a phase II, open-label, randomized trial evaluating the impact of a pre-Emptive Skin treatment regimen on skin toxicities and quality of life in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1351-1357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Balagula Y, Garbe C, Myskowski PL, Hauschild A, Rapoport BL, Boers-Doets CB, Lacouture ME. Clinical presentation and management of dermatological toxicities of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:129-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Craven O, Hughes CA, Burton A, Saunders MP, Molassiotis A. Is a nurse-led telephone intervention a viable alternative to nurse-led home care and standard care for patients receiving oral capecitabine? Results from a large prospective audit in patients with colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2013;22:413-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewer: Kim SU, Pan JJ, Romeo R, Xu LF S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL