Published online Jul 27, 2014. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v6.i7.527

Revised: May 20, 2014

Accepted: June 10, 2014

Published online: July 27, 2014

Processing time: 134 Days and 22.7 Hours

Acute fatty liver of pregnancy is a rare disease that affects women in the third trimester of pregnancy. Although infrequent, the disease can cause maternal mortality. The diagnosis is not always clear until the pregnancy is terminated, and significant complications, such as acute pancreatitis, can occur. Pancreatic involvement typically only occurs in severe cases after the development of hepatic and renal impairment. To date, little knowledge is available regarding how the disease causes pancreatitis. Treatment involves supportive measures and pregnancy interruption. In this report, we describe a case of a previously healthy 26-year-old woman at a gestational age of 27 wk and 6 d who was admitted with severe abdominal pain and vomiting. This case illustrates the clinical and laboratory overlap between acute fatty liver of pregnancy and pancreatitis, highlighting the difficulties in differentiating each disease. Furthermore, the hypothesis for this overlapping is presented, and the therapeutic options are discussed.

Core tip: A previously healthy 26-year-old woman at 27 wk and 6 d of pregnancy was referred for investigation of abdominal pain. She presented with complaints of diffuse abdominal pain with nausea and vomiting associated with hepatic and renal dysfunction. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy and severe acute pancreatitis were diagnosed. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy is rarely associated with severe acute pancreatitis, which can complicate the diagnosis. The possible mechanisms involved in this association and the current therapies are discussed, focusing on the relevant aspects to improve the management of similar cases.

- Citation: de Oliveira CV, Moreira A, Baima JP, Franzoni LC, Lima TB, Yamashiro FDS, Coelho KYR, Sassaki LY, Caramori CA, Romeiro FG, Silva GF. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy associated with severe acute pancreatitis: A case report. World J Hepatol 2014; 6(7): 527-531

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v6/i7/527.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v6.i7.527

Acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP) is a disorder unique to pregnancy that is characterized by microvesicular fatty infiltration of hepatocytes[1]. AFLP was first described in 1940 and was initially considered fatal[2]. However, early diagnosis has dramatically improved the prognosis and maternal mortality; therefore, maternal mortality is currently the exception rather than the rule[1]. AFLP typically occurs in the third quarter of pregnancy, but it is not always diagnosed prior to delivery, as was the case described herein.

The most common initial symptoms are anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and jaundice. A condition that must be excluded is hemolytic anemia elevated liver function and low platelet count syndrome (HELLP) syndrome, which is characterized by hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count. AFLP and HELLP syndrome can occur together in some overlapping cases, making the diagnosis more difficult. However, the signs of liver failure, such as hypoglycemia and hepatic encephalopathy, are suggestive of AFLP. Additionally, HELLP syndrome is likely to occur in patients with hypertension, whereas AFLP often occurs in the absence of hypertension. The differential diagnosis of these two diseases was evaluated in a recent study, which indicated that the incorporation of antithrombin activity less than 65% into the diagnostic criteria for AFLP may facilitate prompt diagnosis of this disease[3].

A previously healthy 26-year-old woman at a gestational age of 27 wk and 6 d was referred to our hospital due to a diagnostic hypothesis of acute appendicitis. She was complaining of diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting during the week. During her physical exam, she was pale and prostrated with mild tachycardia (108 beats/min) and normal blood pressure (110/70 mmHg). No signs of acute appendicitis were noted, but she displayed a potent and diffuse abdominal pain. Cardiotocography revealed signs of fetal distress, so an emergency cesarean section was performed. During the surgery, the possibility of appendicitis was eliminated. Because the newborn displayed bradycardia and an absence of heartbeats at delivery, he was submitted to initial resuscitation protocols and sent to the intensive care unit (ICU). Laboratory tests on the mother revealed leukocytosis, anemia, and hepatic and renal impairment, but no significant proteinuria was found (Table 1).

| Blood tests | Admission | 48 h after admission | Hospital discharge | 1 yr after discharge |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.8 | 11.2 | - | - |

| Leukocyte count (mm3) | 24000 | 21500 | - | - |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 586 | 71 | 91 | 76 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 532 | 392 | 248 | - |

| g-GTP (U/L) | 282 | 325 | 234 | - |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 8.4 | 7.7 | - | - |

| Amylase (U/L) | 460 | 642 | - | 59 |

| LDH (U/L) | 938 | 977 | - | - |

| ALT (U/L) | 202 | 112 | 34 | 15 |

| AST (U/L) | 343 | 179 | 38 | 17 |

| TB (mg/dL) | 4.0 | 4.9 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 2.6 | 3.3 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 78 | 85 | 20 | 28 |

| INR | 2.13 | 2.78 | 1.16 | 0.98 |

| Proteinuria | 0.06 g/ 24 h | 0.03 g/ 24 h | - | - |

Abdominal ultrasonography revealed only pancreatic edema without signs of biliary obstruction. After the delivery, abdominal computed tomography (CT), upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, and biochemical tests were performed. The endoscopy was performed exclusively to investigate the possibility of peptic ulcer or other gastroduodenal diseases, but no pathological findings were found. The CT showed only pancreatic edema without peripancreatic collections (Figure 1). Given that the amylase increase was greater than sixfold higher than the normal upper limit and that pancreatic edema was confirmed by ultrasonography and CT exams, the presence of pancreatitis was conclusive. According to the Ranson criteria, the patient had a severe disease that achieved 4 points at admission based on the leukocyte count, aspartate aminotransferase, glycemia, and lactate dehydrogenase values (Table 1). Additionally, she had acute renal failure and achieved 14 points according to the APACHE II criteria, which corresponds to an estimated 18.6% risk of hospital death.

The patient developed somnolence and exhibited a progressive decrease in her level of consciousness. Tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation were needed, so she was transferred to the ICU. At this time, the blood glucose remained normal, but she had abdominal distension and decreased bowel sounds. Then, the diagnostic hypotheses changed to acute liver failure, severe acute pancreatitis, and renal failure. Suddenly, she presented recurrent episodes of hypoglycemia, even with continuous dextrose infusion and parenteral nutrition. In response to these new symptoms, AFLP became the major diagnostic hypothesis. Serum factor V was normal, so a percutaneous liver biopsy was performed.

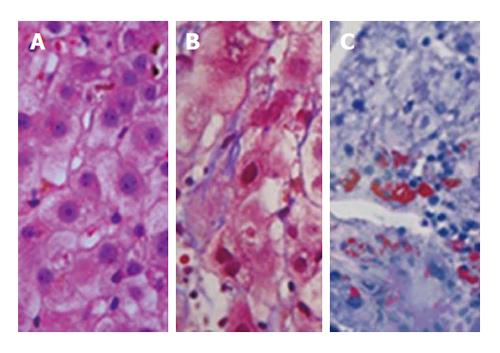

The liver biopsy analysis showed centrilobular microgoticular steatosis, ballooning degeneration, and reticular collapse. The Masson staining showed areas of reticular thickening and intralobular collapse. The “red oil” stain was positive in focal areas, yielding the diagnosis of AFLP (Figure 2).

Seven days following the delivery, she exhibited a clear improvement in consciousness level and liver function tests. She was discharged on postoperative day 24 and returned to the hospital 4 mo later without neurological sequelae. Additionally, laboratory tests and abdominal CT were normal. Despite the problems during the birth, her child exhibited normal development.

AFLP is a rare condition that affects approximately 1 in 7000 to 1 in 20000 births[4-8]. AFLP is more common in women with multiple pregnancies and, possibly, in underweight women. However, this case of AFLP occurred in a primiparous, normal-weight woman but not delivering twins.

Approximately half of AFLP patients display signs of preeclampsia at the beginning of or at some time during the course of the disease[9]. Extrahepatic complications may occur, which can be life-threatening[10,11]. The patients rarely develop pancreatitis, which can be severe. Similar to the case described herein, pancreatitis is typically noticed only after the development of hepatic and renal dysfunction[12]. In this case, the patient had AFLP with severe acute pancreatitis, an association that is rarely documented in the literature. The acute renal failure was a complication of the pancreatitis, so it was treated only by supportive measurements and the delivery, thereby confirming that it was a consequence of the underlying disease. No renal replacement therapy was needed. The liver function tests demonstrated severe hepatic impairment, which was the cause of the jaundice. Therefore, even in the presence of severe pancreatitis, liver disease remained the major disease.

Women with AFLP have impaired liver function with increased bilirubin and transaminase levels and leukocyte counts, which are typically higher than those observed in a normal pregnancy. The platelet count can be reduced with or without additional signs of disseminated intravascular coagulation in association with a significant reduction of antithrombin III[13]. Severely affected patients also have elevated serum ammonia, prolonged prothrombin times, and hypoglycemia caused by liver failure. Acute renal failure and hyperuricemia are often present[14]. However, in the case presented, the recurrent episodes of hypoglycemia, even with appropriate correction, were the main diagnostic clue.

The association between AFLP and inherited defects in the mitochondrial beta-oxidation of fatty acids, especially the impairment of long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCHAD), suggests that some affected women and fetuses have an inherited enzyme deficiency in beta-oxidation that predisposes the mother to this disorder[15-17]. LCHAD catalyzes the third step of the beta-oxidation of fatty acids in the mitochondrion (the formation of 3-ketoacyl-CoA from 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA). The accumulation of long-chain metabolites of 3-hydroxyacyl produced by the fetus or placenta is toxic to the liver and can serve as the cause of the liver disease. The role of the pathogenesis of LCHAD in AFLP has been illustrated in various studies[18-20].

The mechanism by which pancreatitis may develop as a complication of fatty liver of pregnancy is not well understood because this association is rare. Our hypothesis is that the accumulation of long-chain metabolites of 3-hydroxyacyl is toxic to the liver and the pancreatic tissue. Thus, the pancreas could be affected when an increased concentration of these metabolites is present, as occurs in cases of severe hepatic disease. This hypothesis serves as a reasonable explanation for the pancreatic impairment displayed in this case of hepatic failure.

The diagnosis of LCHAD deficiency in newborns can save lives; therefore, all women with AFLP and their children should be administered a molecular test for LCHAD, which should at least evaluate the most common mutation, namely, G1528C[21,22]. In the present case, it was not possible to perform this type of test because it was not available.

The clinical diagnosis of AFLP is typically performed according to the definition, presentation, and laboratory-compatible image results. The liver imaging is primarily used to exclude other diagnoses, such as hepatic infarction and hematoma[23]. Various authors reported steatosis on ultrasound or CT, but these tests are only useful for performing comparative analyses[24,25]. The AFLP diagnosis can only be made through a liver biopsy showing microvesicular fatty infiltration in hepatocytes. The fat droplets are centrally distributed around the cellular nuclei, giving the cytoplasm a foamy aspect and typically sparing the cells around the portal tract[26]. A special staining (oil red) must be used to confirm the diagnosis in patients without obvious vacuolation[27,28]. As the liver biopsy is invasive, it is not always performed. Liver biopsy should be performed with caution during pregnancy and be reserved for cases where the diagnosis remains unclear.

A specific treatment is not available for AFLP. The primary treatment is delivery, which typically occurs on an emergency basis after maternal stabilization via the infusion of glucose and reversal of the coagulation disturbances. Because hypoglycemia is common and dangerous, glucose levels should be monitored until liver function normalizes[7]. It is typically necessary to treat hypoglycemia with the continuous infusion of a 10% glucose solution. Some patients with severe hypoglycemia may require additional bolus administrations of 50% glucose[7].

The liver function tests typically begin to normalize after delivery; however, after the first few days, a transient worsening of renal and hepatic function may be observed, followed by a definite improvement. In severe cases, particularly when the diagnosis is delayed, more days of illness can be observed, requiring supportive treatment in an ICU. Mechanical ventilation, dialysis, parenteral nutrition, or surgery to treat bleeding during cesarean delivery may be needed. Even the most severely ill patients can recover without liver disease sequelae[7]. However, substantial morbidity and even maternal mortality may occur[8]. Some reports have also described patients who required liver transplantation, which is rarely needed when a diagnosis and pregnancy termination were achieved in sufficient time[29,30]. A case series of five patients indicated good recovery after plasma exchange and renal replacement therapy, showing that the accumulation of long-chain metabolites of 3-hydroxyacyl is most likely the major cause of the liver disease. The authors suggested that these therapies are safe and effective; thus, they should be used immediately at the onset of hepatic encephalopathy and/or renal failure in AFLP patients[31]. None of the patients treated by plasma exchange and renal replacement therapy developed pancreatitis, indicating that our pancreatic toxicity hypothesis may be correct.

Of note, AFLP can recur in subsequent pregnancies despite negative LCHAD mutation screening results[6,15,18,32-35]. However, the exact risk of recurrence is unknown. Affected women should be advised of this possibility, and a maternal-fetal medicine specialist should closely monitor subsequent pregnancies. Given that the initial symptoms of AFLP can be atypical, the diagnosis can be easily misidentified, leading to multiple organ dysfunctions. Once the diagnosis is confirmed, it is important to be vigilant to avoid serious complications, such as pancreatitis, renal failure, and hypoglycemia, as described here.

We acknowledge Professor Maria Rita Piloto for the article corrections.

A previously healthy 26-year-old woman with a gestational age of 27 wk and 6 d presented with diffuse abdominal pain associated with hepatic and renal failure.

Diffuse abdominal pain and vomiting.

Hemolytic anemia elevated liver function and low platelet count syndrome syndrome.

Amylase: 642 U/L; glucose: 586 mg/dL; alanine aminotransferase: 202 U/L; aspartate aminotransferase: 343 U/L; total bilirubin: 4.0 mg/dL; creatinine: 2.6 mg/dL; urea: 78 mg/dL; international normalized ratio: 2.13.

Pancreatic edema was confirmed by ultrasonography and computed tomography.

The liver biopsy results were compatible with acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP).

Pregnancy interruption and supportive measures.

AFLP rarely presents with severe acute pancreatitis.

Because the early symptoms of AFLP can be uncharacteristic, the disease can be misdiagnosed. It is important to be vigilant to make the correct diagnosis of AFLP and identify complications, such as pancreatitis.

This article describes a rare case with acute fatty liver disease complicated with acute pancreatitis. This is an interesting case report.

| 1. | Bacq Y, Riely CA. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy: the hepatologist’s view. Gastroenterologist. 1993;1:257-264. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Sheehan H. The pathology of acute yellow atrophy and delayed chloroform poisoning. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1940;47:49-53. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Minakami H, Morikawa M, Yamada T, Yamada T, Akaishi R, Nishida R. Differentiation of acute fatty liver of pregnancy from syndrome of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelet counts. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40:641-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Usta IM, Barton JR, Amon EA, Gonzalez A, Sibai BM. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy: an experience in the diagnosis and management of fourteen cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:1342-1347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pockros PJ, Peters RL, Reynolds TB. Idiopathic fatty liver of pregnancy: findings in ten cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1984;63:1-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Reyes H, Sandoval L, Wainstein A, Ribalta J, Donoso S, Smok G, Rosenberg H, Meneses M. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy: a clinical study of 12 episodes in 11 patients. Gut. 1994;35:101-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Castro MA, Fassett MJ, Reynolds TB, Shaw KJ, Goodwin TM. Reversible peripartum liver failure: a new perspective on the diagnosis, treatment, and cause of acute fatty liver of pregnancy, based on 28 consecutive cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:389-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Knight M, Nelson-Piercy C, Kurinczuk JJ, Spark P, Brocklehurst P. A prospective national study of acute fatty liver of pregnancy in the UK. Gut. 2008;57:951-956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Riely CA. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Semin Liver Dis. 1987;7:47-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pereira SP, O’Donohue J, Wendon J, Williams R. Maternal and perinatal outcome in severe pregnancy-related liver disease. Hepatology. 1997;26:1258-1262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kennedy S, Hall PM, Seymour AE, Hague WM. Transient diabetes insipidus and acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;101:387-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Moldenhauer JS, O’brien JM, Barton JR, Sibai B. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy associated with pancreatitis: a life-threatening complication. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:502-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Castro MA, Goodwin TM, Shaw KJ, Ouzounian JG, McGehee WG. Disseminated intravascular coagulation and antithrombin III depression in acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:211-216. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Grünfeld JP, Pertuiset N. Acute renal failure in pregnancy: 1987. Am J Kidney Dis. 1987;9:359-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Schoeman MN, Batey RG, Wilcken B. Recurrent acute fatty liver of pregnancy associated with a fatty-acid oxidation defect in the offspring. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:544-548. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Wilcken B, Leung KC, Hammond J, Kamath R, Leonard JV. Pregnancy and fetal long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency. Lancet. 1993;341:407-408. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Treem WR, Rinaldo P, Hale DE, Stanley CA, Millington DS, Hyams JS, Jackson S, Turnbull DM. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy and long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency. Hepatology. 1994;19:339-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Treem WR, Shoup ME, Hale DE, Bennett MJ, Rinaldo P, Millington DS, Stanley CA, Riely CA, Hyams JS. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy, hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets syndrome, and long chain 3-hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:2293-2300. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Sims HF, Brackett JC, Powell CK, Treem WR, Hale DE, Bennett MJ, Gibson B, Shapiro S, Strauss AW. The molecular basis of pediatric long chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency associated with maternal acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:841-845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yang Z, Zhao Y, Bennett MJ, Strauss AW, Ibdah JA. Fetal genotypes and pregnancy outcomes in 35 families with mitochondrial trifunctional protein mutations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:715-720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rajasri AG, Srestha R, Mitchell J. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP)--an overview. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;27:237-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ibdah JA. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy: an update on pathogenesis and clinical implications. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7397-7404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Strategies for cadaveric organ procurement. Mandated choice and presumed consent. Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs, American Medical Association. JAMA. 1994;272:809-812. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Castro MA, Ouzounian JG, Colletti PM, Shaw KJ, Stein SM, Goodwin TM. Radiologic studies in acute fatty liver of pregnancy. A review of the literature and 19 new cases. J Reprod Med. 1996;41:839-843. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Campillo B, Bernuau J, Witz MO, Lorphelin JM, Degott C, Rueff B, Benhamou JP. Ultrasonography in acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105:383-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bacq Y. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Semin Perinatol. 1998;22:134-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Riely CA, Latham PS, Romero R, Duffy TP. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy. A reassessment based on observations in nine patients. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:703-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Rolfes DB, Ishak KG. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy: a clinicopathologic study of 35 cases. Hepatology. 1985;5:1149-1158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ockner SA, Brunt EM, Cohn SM, Krul ES, Hanto DW, Peters MG. Fulminant hepatic failure caused by acute fatty liver of pregnancy treated by orthotopic liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1990;11:59-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Amon E, Allen SR, Petrie RH, Belew JE. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy associated with preeclampsia: management of hepatic failure with postpartum liver transplantation. Am J Perinatol. 1991;8:278-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Yu CB, Chen JJ, Du WB, Chen P, Huang JR, Chen YM, Cao HC, Li LJ. Effects of plasma exchange combined with continuous renal replacement therapy on acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2014;13:179-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Bacq Y, Assor P, Gendrot C, Perrotin F, Scotto B, Andres C. [Recurrent acute fatty liver of pregnancy]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2007;31:1135-1138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | MacLean MA, Cameron AD, Cumming GP, Murphy K, Mills P, Hilan KJ. Recurrence of acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;101:453-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Barton JR, Sibai BM, Mabie WC, Shanklin DR. Recurrent acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:534-538. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Visconti M, Manes G, Giannattasio F, Uomo G. Recurrence of acute fatty liver of pregnancy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;21:243-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewer: Alcazar JL, Cichoz-Lach H, Shimizu Y, Tsikouras P, Wang CC S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ